Magnetically Sculpted Microfluidics for Continuous-Flow Fractionation of Cell Populations by EpCAM Expression Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Magnetic Immune Labeling

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.4. Fabrication of SMS on Glass Substrates

2.5. Fabrication of Embedded SMS in PDMS Microchannels

2.6. Chip Design and Integrated Assembly

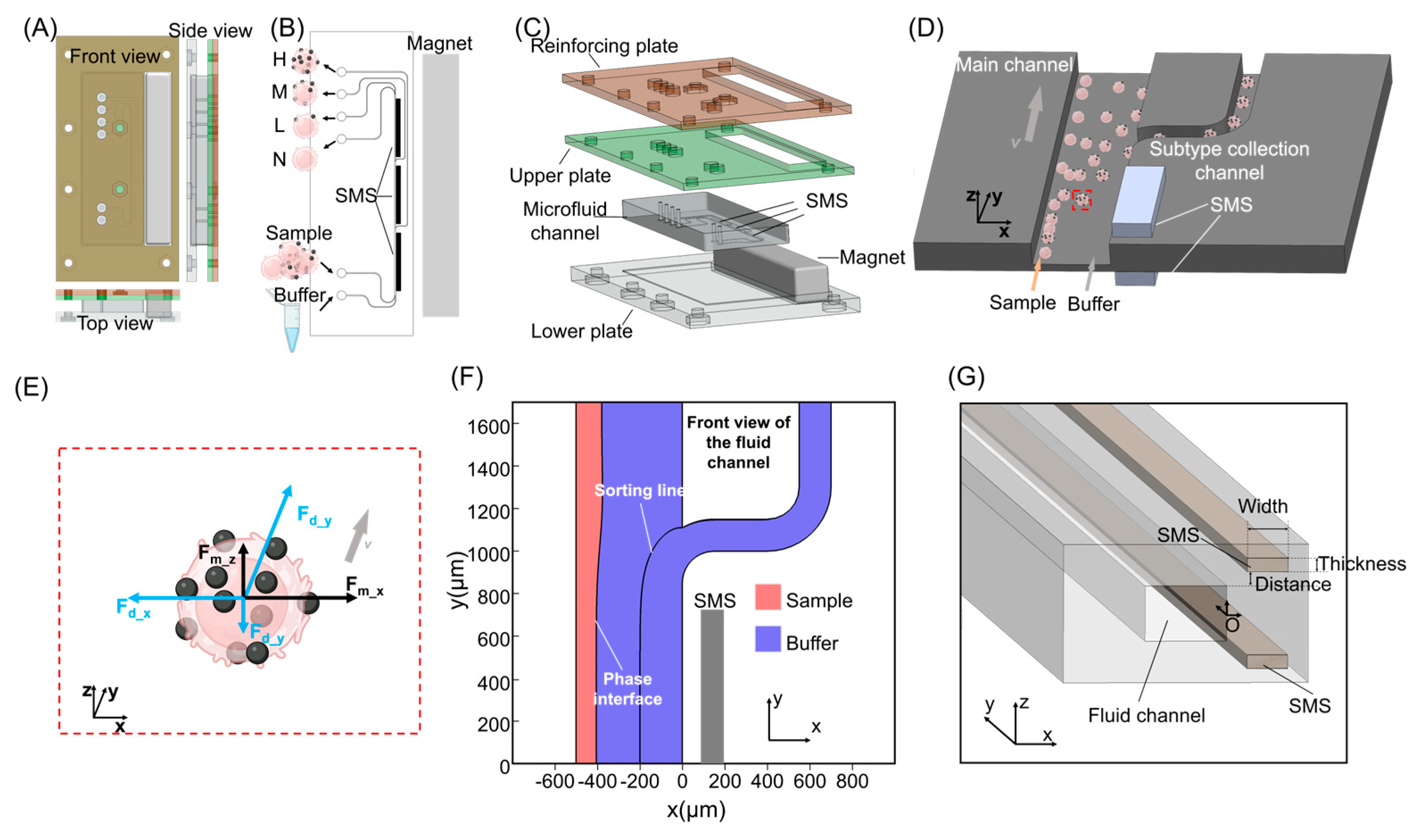

2.7. Principle of Continuous Expression-Level–Dependent Cell Fractionation

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

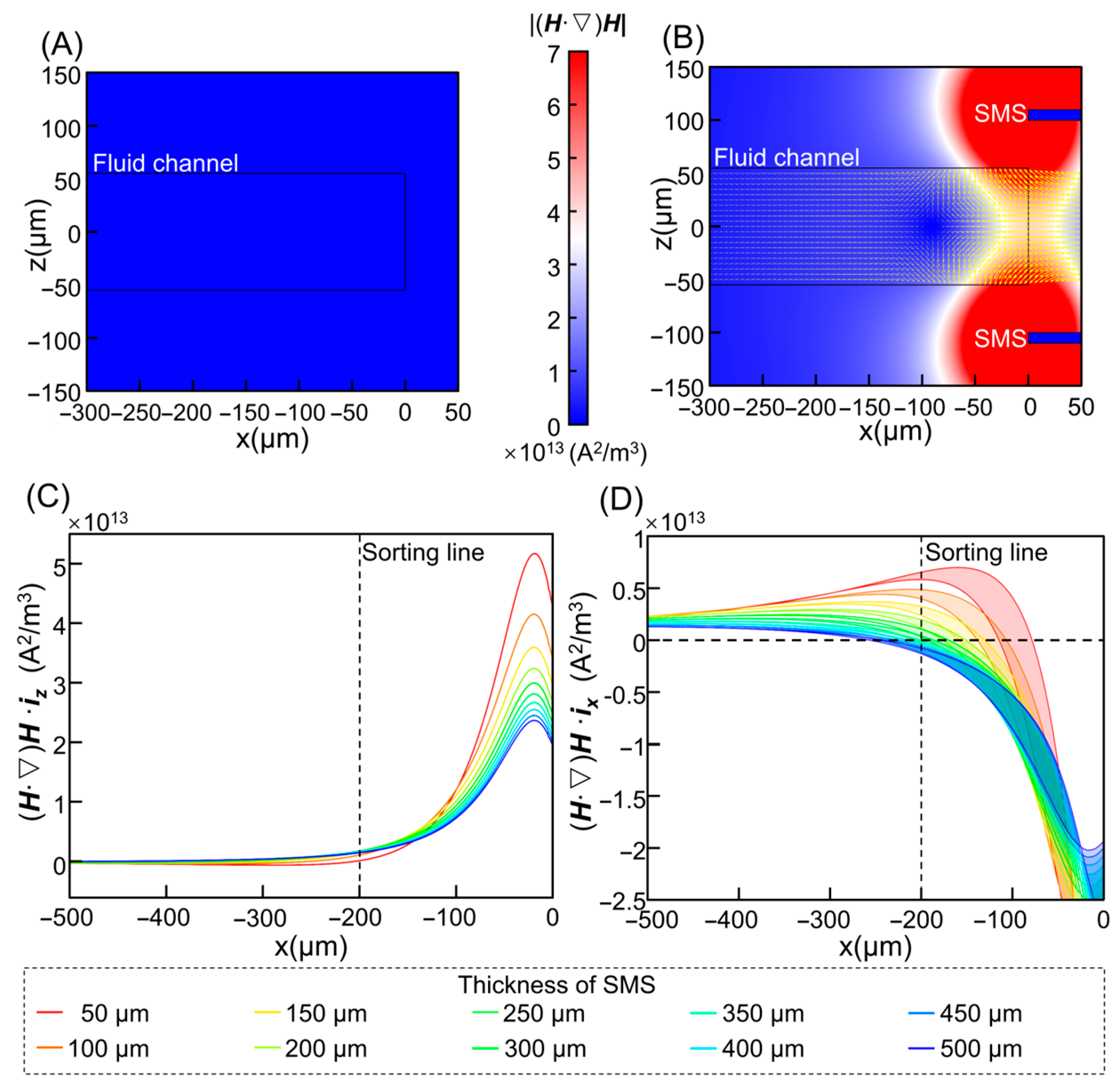

3.1. Flow and Magnetic Field Distribution

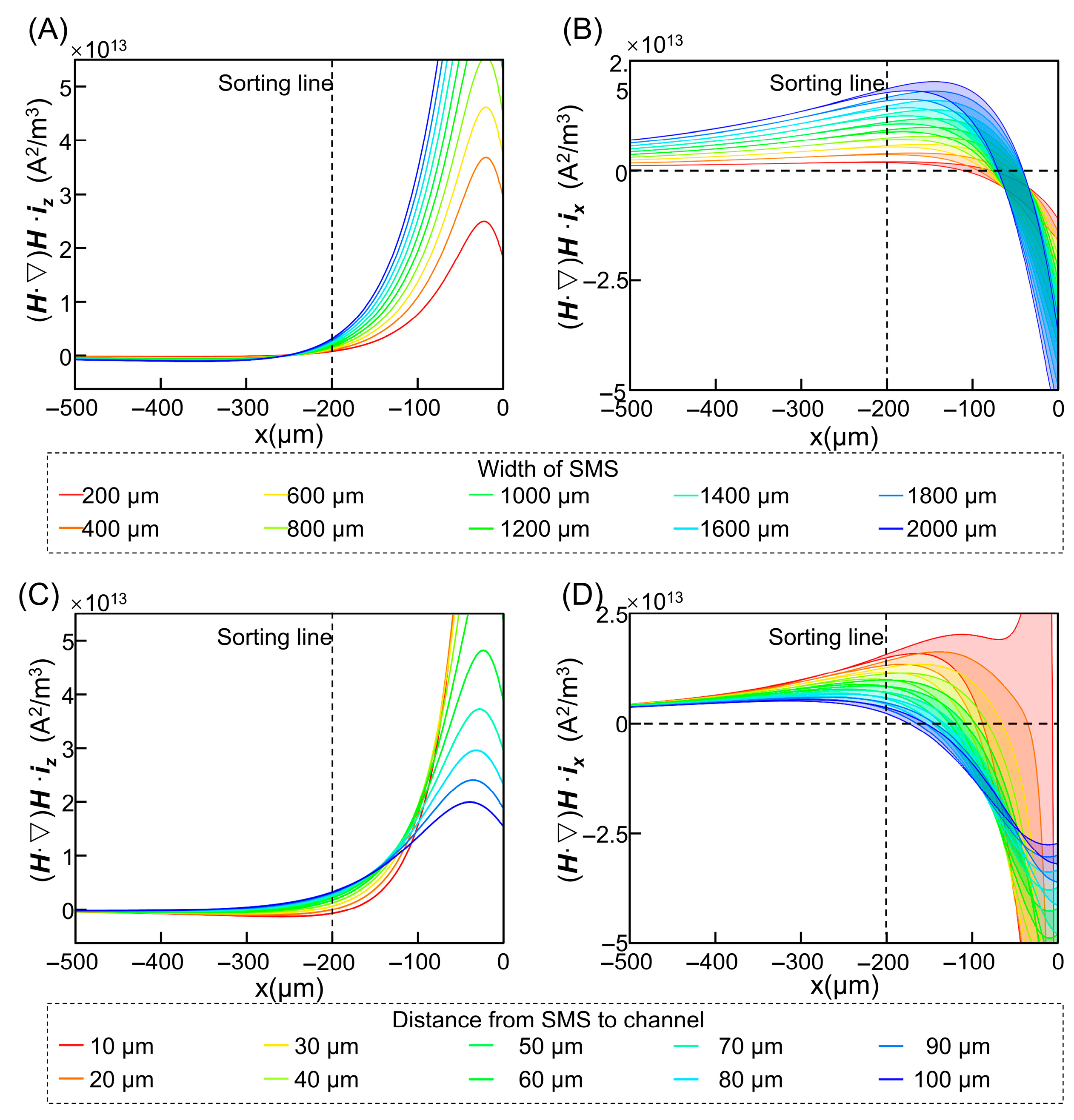

3.2. Optimization of Magnetic Parameters

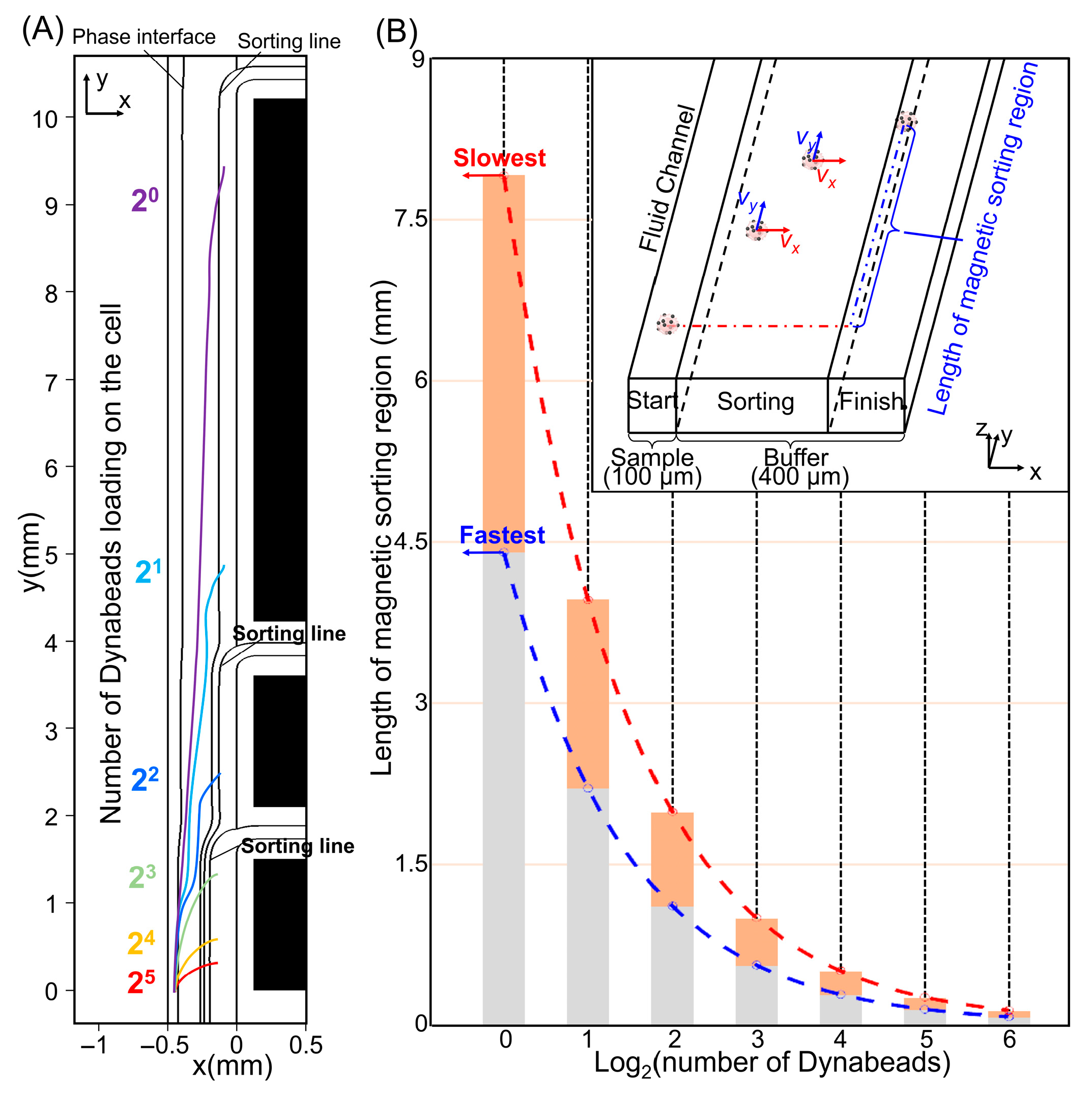

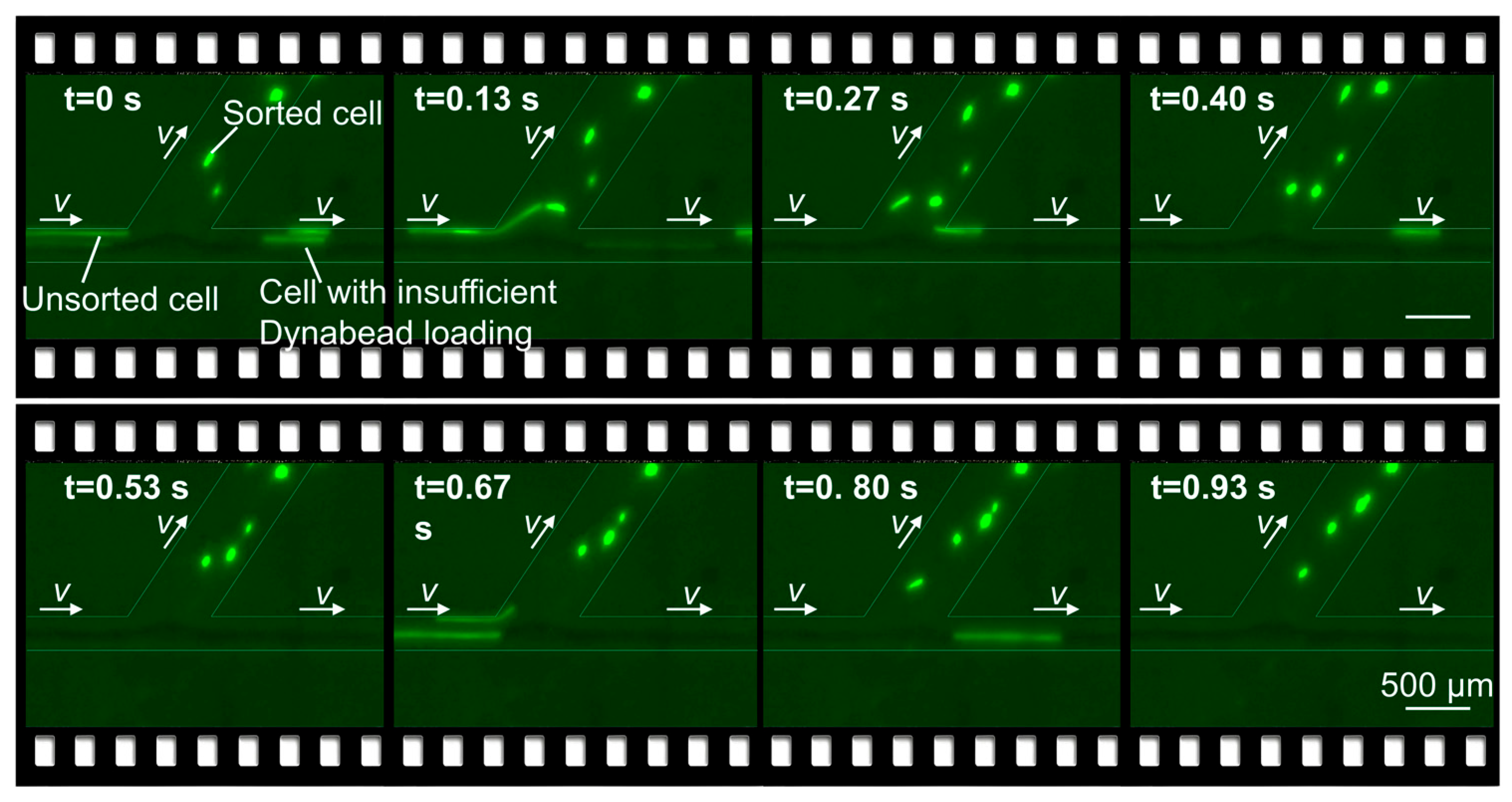

3.3. Cell Motion Simulation and Sorting Results

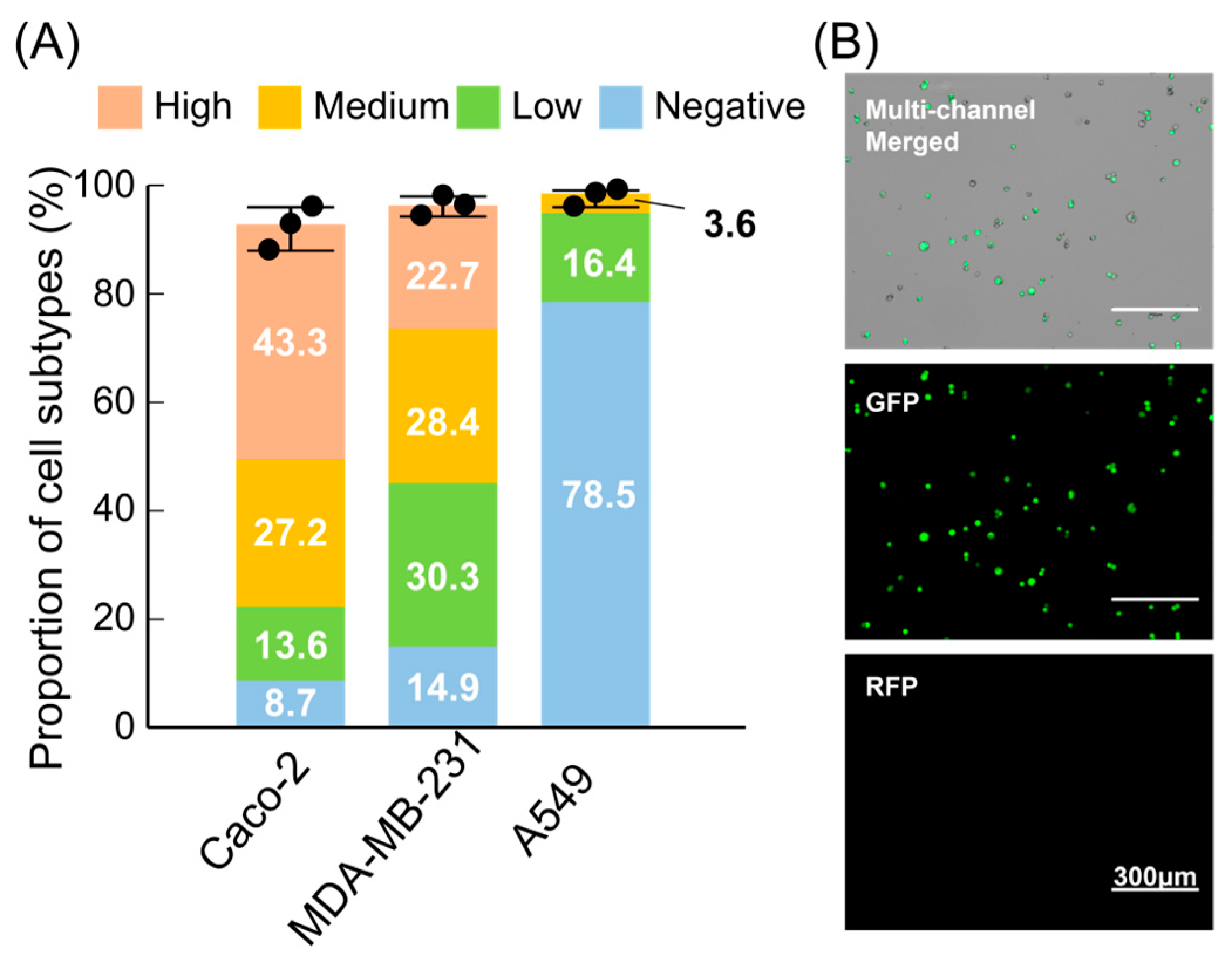

3.4. Benchmarking EpCAM Expression-Level Fractionation Across Multiple Cell Lines

4. Conclusions and Prospects

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMS | soft magnetic strip |

| EpCAM | epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| MACS | magnetic-activated cell sorting |

| SDS-PAGE | sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| PVDF | polyvinylidene difluoride |

| HRP | horseradish peroxidase |

References

- Lenshof, A.; Laurell, T. Continuous separation of cells and particles in microfluidic systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, T.; Peng, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Wu, S.; Liu, S.; Dong, Y.; Xie, S.; Ma, S. Mesenchymal phenotype of circulating tumor cells is associated with distant metastasis in breast cancer patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.S.; Liu, Z.N.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.X.; Shen, H.; Hou, L.J.; Ding, Y. New advances in circulating tumor cell-mediated metastasis of breast cancer. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 19, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, L.; Wikman, H.; Pantel, K. Biology and clinical significance of circulating tumor cell subpopulations in lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2017, 6, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Giner, F.; Aceto, N. Tracking cancer progression: From circulating tumor cells to metastasis. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.; Wang, Y.J.; Plummer, S.; Dickerson, A.; Yu, M. An Image-Based Identification of Aggressive Breast Cancer Circulating Tumor Cell Subtypes. Cancers 2023, 15, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, L.; Greimeier, S.; Riethdorf, S.; Rohlfing, T.; Kaune, M.; Busenbender, T.; Strewinsky, N.; Dyshlovoy, S.; Joosse, S.; Peine, S.; et al. Transcriptional profiles of circulating tumor cells reflect heterogeneity and treatment resistance in advanced prostate cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, B.; Aldridge, P.M.; Atwal, R.S.; Philpott, D.; Zhang, M.; Masud, S.N.; Labib, M.; Tong, A.H.Y.; Sargent, E.H.; Angers, S.; et al. High-throughput genome-wide phenotypic screening via immunomagnetic cell sorting. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubouchi, A.; An, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Yanagihashi, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Murata, Y.; Teranishi, K.; Ishiguro, S.; Aburatani, H.; Yachie, N.; et al. Pooled CRISPR screening of high-content cellular phenotypes using ghost cytometry. Cell Rep. Methods 2024, 4, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajkarim, M.C.; Karjalainen, E.; Osipovitch, M.; Dimopoulos, K.; Gordon, S.L.; Ambri, F.; Rasmussen, K.D.; Grønbæk, K.; Helin, K.; Wennerberg, K.; et al. Comprehensive and unbiased multiparameter high-throughput screening by compaRe finds effective and subtle drug responses in AML models. Elife 2022, 11, e73760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yao, H.; Lin, J.-M. Recent advancements in single-cell metabolic analysis for pharmacological research. J. Pharm. Anal. 2023, 13, 1102–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Liang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Advances in precise cell manipulation. Droplet 2025, 4, e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Jin, F.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, Y. Recent advances in single cell manipulation and biochemical analysis on microfluidics. Analyst 2019, 144, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Kim, K.; Lee, W.G. Cell manipulation in microfluidics. Biofabrication 2013, 5, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmanickam, L.; Jayasooriya, V.; Vemuri, M.S.; Tida, U.R.; Nawarathna, D. Recent advances in dielectrophoresis toward biomarker detection: A summary of studies published between 2014 and 2021. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, C.; Cai, Y.; Su, F.; Han, C.; Yu, D.; Luo, Y.; Xing, X. Dielectrophoretic cell sorting with high velocity enabled by two-layer sidewall microelectrodes extending along the entire channel. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 410, 135669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Ji, X.-H.; Liu, K.; He, R.-X.; Zhao, L.-B.; Guo, Z.-X.; Liu, W.; Guo, S.-S.; Zhao, X.-Z. Droplet electric separator microfluidic device for cell sorting. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 193701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, A.; Jiang, X.; Wahid, A.; Wang, H.; Cao, C.; Xiao, H. Free-flow zone electrophoresis facilitated proteomics analysis of heterogeneous subpopulations in H1299 lung cancer cells. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1227, 340306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, T.; Johansson, L.; Juliano, P.; McArthur, S.L.; Manasseh, R. Ultrasonic Separation of Particulate Fluids in Small and Large Scale Systems: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 16555–16576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, W.L.; Mutafopulos, K.; Spink, P.; Rambach, R.W.; Franke, T.; Weitz, D.A. Enhanced surface acoustic wave cell sorting by 3D microfluidic-chip design. Lab. Chip 2017, 17, 4059–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.; Xiong, Y.; Jin, X.; Shao, M.; Tong, X.; Farag, S.; Zborowski, M. Quantification of non-specific binding of magnetic micro- and nanoparticles using cell tracking velocimetry: Implication for magnetic cell separation and detection. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 105, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, P.M.; Mukhopadhyay, M.; Ahmed, S.U.; Zhou, W.; Christinck, E.; Makonnen, R.; Sargent, E.H.; Kelley, S.O. Prismatic Deflection of Live Tumor Cells and Cell Clusters. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 12692–12700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.D.; Kim, U.; Soh, H.T. Multitarget magnetic activated cell sorter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18165–18170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, T.; Moore, L.R.; Jing, Y.; Haam, S.; Williams, P.S.; Fleischman, A.J.; Roy, S.; Chalmers, J.J.; Zborowski, M. Continuous flow magnetic cell fractionation based on antigen expression level. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2006, 68, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, C.Y.; Peh, G.S.; Gauthaman, K.; Bongso, A. Separation of SSEA-4 and TRA-1-60 labelled undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells from a heterogeneous cell population using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2009, 5, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlido, L.; Azevedo, A.M.; Roque, A.C.; Aires-Barros, M.R. Magnetic separations in biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Immunomagnetic separation of circulating tumor cells with microfluidic chips and their clinical applications. Biomicrofluidics 2020, 14, 041502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Dubash, T.D.; Edd, J.F.; Jewett, M.K.; Garre, S.G.; Karabacak, N.M.; Rabe, D.C.; Mutlu, B.R.; Walsh, J.R.; Kapur, R.; et al. Ultrahigh-throughput magnetic sorting of large blood volumes for epitope-agnostic isolation of circulating tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16839–16847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, Q.; Teo, A.J.T.; Yan, S.; Ooi, C.H.; Li, W.; Nguyen, N.-T. Fundamentals of Differential Particle Inertial Focusing in Symmetric Sinusoidal Microchannels. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 4077–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, N.M.; Spuhler, P.S.; Fachin, F.; Lim, E.J.; Pai, V.; Ozkumur, E.; Martel, J.M.; Kojic, N.; Smith, K.; Chen, P.-I.; et al. Microfluidic, marker-free isolation of circulating tumor cells from blood samples. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudineh, M.; Aldridge, P.M.; Ahmed, S.; Green, B.J.; Kermanshah, L.; Nguyen, V.; Tu, C.; Mohamadi, R.M.; Nam, R.K.; Hansen, A.; et al. Tracking the dynamics of circulating tumour cell phenotypes using nanoparticle-mediated magnetic ranking. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudineh, M.; Sargent, E.H.; Pantel, K.; Kelley, S.O. Profiling circulating tumour cells and other biomarkers of invasive cancers. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besant, J.D.; Mohamadi, R.M.; Aldridge, P.M.; Li, Y.; Sargent, E.H.; Kelley, S.O. Velocity valleys enable efficient capture and spatial sorting of nanoparticle-bound cancer cells. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 6278–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, K.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Lane, N.; Huebschman, M.; Uhr, J.W.; Frenkel, E.P.; Zhang, X. Microchip-based immunomagnetic detection of circulating tumor cells. Lab. Chip 2011, 11, 3449–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wu, L.-L.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Hu, J.; Tang, M.; Qi, C.-B.; Li, N.; Pang, D.-W. Biofunctionalized magnetic nanospheres-based cell sorting strategy for efficient isolation, detection and subtype analyses of heterogeneous circulating hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 85, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Cui, G.; Wu, X.; Yang, M.; Piao, Y.; Bai, Z.; Wang, L.; Kraft, M.; Zhao, W.; et al. A magnetic nanoparticle assisted microfluidic system for low abundance cell sorting with high recovery. Micro Nano Eng. 2022, 15, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bshara-Corson, S.; Burwell, A.; Tiemann, T.; Murray, C. Digital Magnetic Sorting for Fractionating Cell Populations with Variable Antigen Expression in Cell Therapy Process Development. Magnetochemistry 2024, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlani, E.P.; Ng, K.C. Analytical model of magnetic nanoparticle transport and capture in the microvasculature. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2006, 73, 061919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ahmed, S.; Labib, M.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Bavaghar-Zaeimi, F.; Shokri, N.; Blanco, S.; Karim, S.; Czarnecka-Kujawa, K.; et al. Isolation of tumour-reactive lymphocytes from peripheral blood via microfluidic immunomagnetic cell sorting. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 1188–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJesus, R.; Moretti, F.; McAllister, G.; Wang, Z.; Bergman, P.; Liu, S.; Frias, E.; Alford, J.; Reece-Hoyes, J.S.; Lindeman, A.; et al. Functional CRISPR screening identifies the ufmylation pathway as a regulator of SQSTM1/p62. Elife 2016, 5, e17290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigdar, S.; Qian, C.; Lv, L.; Pu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Marappan, M.; Lin, J.; Wang, L.; Duan, W. The use of sensitive chemical antibodies for diagnosis: Detection of low levels of EpCAM in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Gu, L.; Lyu, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, T.; et al. Dynamic expression of EpCAM in primary and metastatic lung cancer is controlled by both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Cancers 2022, 14, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martowicz, A.; Spizzo, G.; Gastl, G.; Untergasser, G. Phenotype-dependent effects of EpCAM expression on growth and invasion of human breast cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 501. [Google Scholar]

- Evani, S.J.; Prabhu, R.G.; Gnanaruban, V.; Finol, E.A.; Ramasubramanian, A.K. Monocytes mediate metastatic breast tumor cell adhesion to endothelium under flow. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Stewart, A.G.; Lee, P.V. On-chip cell mechanophenotyping using phase modulated surface acoustic wave. Biomicrofluidics 2019, 13, 024107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of cell compressibility changes during epithelial–mesenchymal transition based on acoustofluidic microdevice. Biomicrofluidics 2021, 15, 064101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, A.; Piairo, P.; Teixeira, A.; Ferreira, D.; Cotton, S.; Rodrigues, C.; Chícharo, A.; Abalde-Cela, S.; Santos, L.L.; Lima, L.; et al. Discriminating epithelial to mesenchymal transition phenotypes in circulating tumor cells isolated from advanced gastrointestinal cancer patients. Cells 2022, 11, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassano, D.; Bogni, A.; La Spina, R.; Gilliland, D.; Ponti, J. Investigating the cellular uptake of model nanoplastics by single-cell ICP-MS. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, A.A.; Dufva, M. Heterogenous morphogenesis of Caco-2 cells reveals that flow induces three-dimensional growth and maturation at high initial seeding cell densities. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J. Magnetically Sculpted Microfluidics for Continuous-Flow Fractionation of Cell Populations by EpCAM Expression Level. Micromachines 2026, 17, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010009

Liang Z, Guo X, Zhang X, Chen Y, Du C, Ma Y, Wang J. Magnetically Sculpted Microfluidics for Continuous-Flow Fractionation of Cell Populations by EpCAM Expression Level. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Zhenwei, Xiaolei Guo, Xuanhe Zhang, Yiqing Chen, Chuan Du, Yuan Ma, and Jiadao Wang. 2026. "Magnetically Sculpted Microfluidics for Continuous-Flow Fractionation of Cell Populations by EpCAM Expression Level" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010009

APA StyleLiang, Z., Guo, X., Zhang, X., Chen, Y., Du, C., Ma, Y., & Wang, J. (2026). Magnetically Sculpted Microfluidics for Continuous-Flow Fractionation of Cell Populations by EpCAM Expression Level. Micromachines, 17(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010009