Dynamic Electrophoresis of an Oil Drop

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Boundary Conditions

2.3. Equilibrium Distributions of Ionic Concentration, Charge, and Electric Potential, and Surface Charge Density in the Absence of an Applied Electric Field

2.4. Weak Field Approximation: Linearization

2.5. General Electrophoretic Mobility Formula

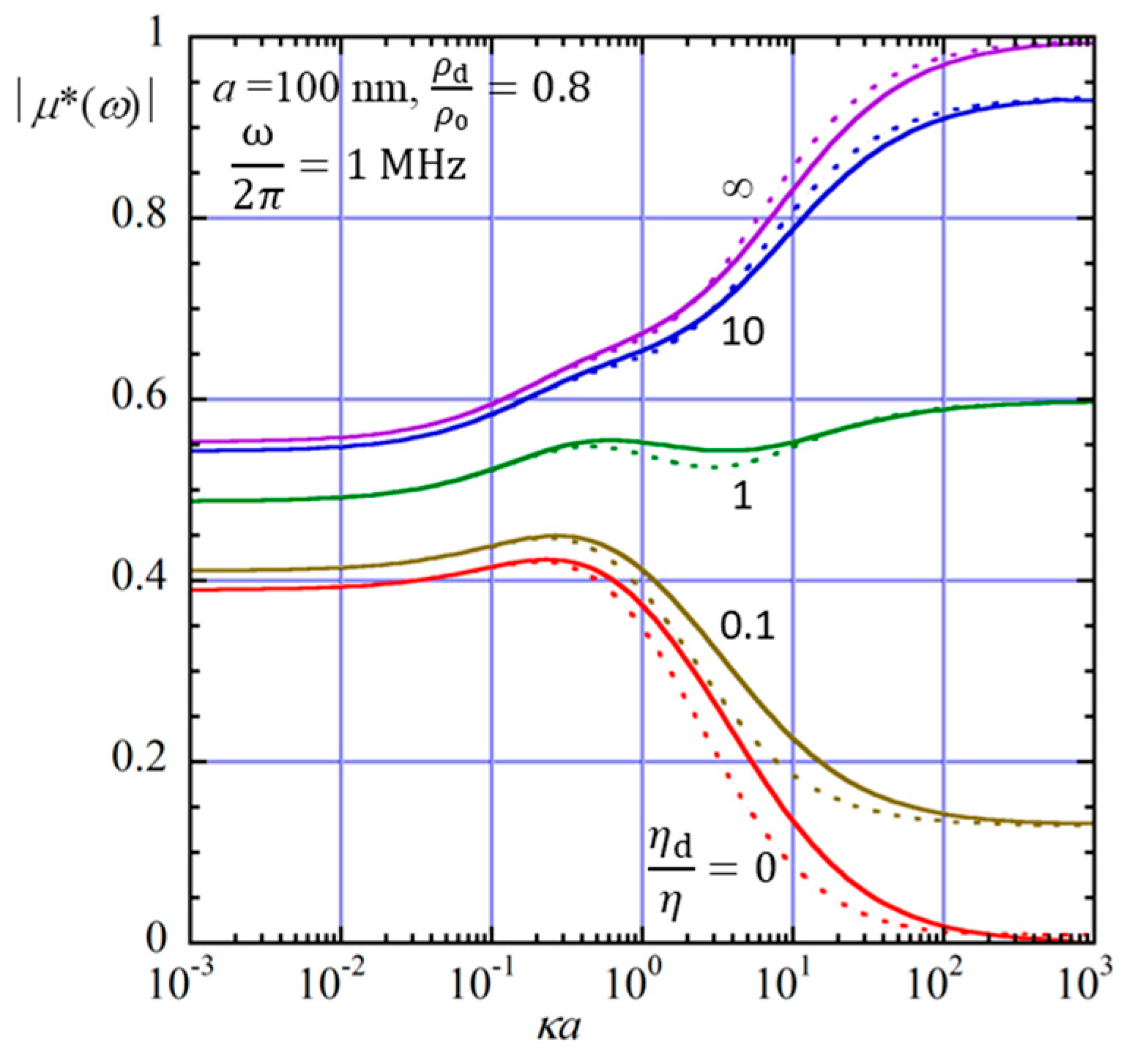

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Landau, D.L. Theory of the stability of strongly charged lyophobic sols and of the adhesion of strongly charged particles in solutions of electrolytes. Acta Phys. Chim. USSR 1941, 14, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwey, E.J.W.; Overbeek, J.T.G. Theory of the Stability of Lyophobic Colloids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin, B.V. Theory of Stability of Colloids and Thin Films; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- von Smoluchowski, M. Elektrische endosmose und strömungsströme. In Handbuch der Elektrizität und des Magnetismus, Band II Stationäre Ströme; Greatz, E., Ed.; Barth: Leipzig, Germany, 1921; pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Hückel, E. Die Kataphorese der Kugel. Phys. Z 1924, 25, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, D.C. The cataphoresis of suspended particles. Part I. The equation of cataphoresis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1931, 133, 106–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, J.T.G. Theorie der Elektrophorese. Kolloid-Beihefte 1943, 54, 287–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F. The cataphoresis of spherical, solid non-conducting particles in a symmetrical electrolyte. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1950, 203, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, P.H.; Loeb, A.L.; Overbeek, J.T.G. Calculation of the electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloid particle. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1966, 22, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukhin, S.S.; Derjaguin, B.V. Nonequilibrium double layer and electrokinetic phenomena. In Surface and Colloid Science; Matievic, E., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974; Volume 2, pp. 273–336. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R.W.; White, L.R. Electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1978, 74, 1607–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.W.; Hunter, R.J. The electrophoretic mobility of large colloidal particles. Can. J. Chem. 1981, 59, 1878–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, T.G.M. Colloidal Hydrodynamics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lyklema, J. Fundamentals of Interface and Colloid Science, Solid-Liquid Interfaces; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.V. (Ed.) Interfacial Electrokinetics and Electrophoresis; Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dukhin, A.S.; Goetz, P.J. Ultrasound for Characterizing Colloids: Particle Sizing, Zeta Potential, Rheology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Spasic, A.; Hsu, J.-P. (Eds.) Finely Dispersed Particles: Micro-, Nano-, Atto-Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masliyah, J.H.; Bhattacharjee, S. Electrokinetic and Colloid Transport Phenomena; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tadros, T.F. (Ed.) Colloid Stability: The Role of Surface Forces—Part 1; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, R.J. Zeta Potential in Colloid Science: Principles and Applications; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. Theory of Electrophoresis and Diffusiophoresis of Highly Charged Colloidal Particles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dukhin, A.S.; Xu, R. Zeta Potential; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R.W. Electro-acoustic effects in a dilute suspension of spherical particles. J. Fluid Mech. 1988, 190, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babchin, A.J.; Chow, R.S.; Sawatzky, R.P. Electrokinetic measurements by electroacoustical methods. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1989, 30, 111–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatzky, R.P.; Babchin, A. Hydrodynamics of electrophoretic motion in an alternating electric field. J. Fluid Mech. 1993, 246, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixman, M. Thin double layer approximation for electrophoresis and dielectric response. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 78, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.O.; Texter, J.; Scales, P. Frequency dependence of electroacoustic (electrophoretic) mobilities. Langmuir 1991, 7, 1993–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangelsdorf, C.S.; White, L.R. Electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle in an oscillating electric field. J Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1992, 88, 3567–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangelsdorf, C.S.; White, L.R. Low-zeta-potential analytic solution for the electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle in an oscillating electric field. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1993, 160, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Dynamic electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996, 179, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Approximate analytic expression for the dynamic electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle in an oscillating electric field. Langmuir 2005, 21, 9818–9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F. The cataphoresis of spherical fluid droplets in electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 1951, 19, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levich, V.G. Physicochemical Hydrodynamics; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S.; O’Brien, R.N. A theory of electrophoresis of charged mercury drops in aqueous electrolyte solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1973, 43, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baygents, J.C.; Saville, D.A. Electrophoresis of drops and bubbles. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1991, 87, 1883–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baygents, J.C.; Saville, D.A. Electrophoresis of small particles and fluid globules in weak electrolytes. J. Colloid Interface Sc. 1991, 146, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. A Simple expression for the electrophoretic mobility of charged mercury drops. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 189, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.P.; He, Y.Y.; Lee, E. Sedimentation velocity and potential in a concentrated suspension of charged liquid drops. Langmuir 2008, 24, 11361–11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, O.; Frankel, I.; Yariv, E. Electrokinetic flows about conducting drops. J. Fluid Mech. 2013, 722, 394–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, O.; Frankel, I.; Yariv, E. Electrophoresis of bubbles. J. Fluid Mech. 2014, 753, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Majee, P.S. Nonlinear electrophoresis of a charged polarizable liquid droplet. Phys. Fluids 2018, 30, 082008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J. Electrokinetic spectra of dilute surfactant-stabilized nano-emulsions. J. Fluid Mech. 2020, 902, A15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; Afuwape, G. Dynamic mobility of surfactant-stabilized nano-drops: Unifying equilibrium thermodynamics, electro-kinetics and Marangoni effects. J. Fluid Mech. 2020, 895, A14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Fan, L.; Jian, E.; Lee, E. Electrophoresis of a highly charged dielectric fluid droplet in electrolyte solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 598, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, M.; Zargartalebi, M.; Benneker, A.M. Mechanistic studies of droplet electrophoresis: A review. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.Y.; Fan, L.; Tseng, J.; Lin, J.; Tseng, A.; Lee, E. Electrophoresis of a highly charged fluid droplet in dilute electrolyte solutions: Analytical Hückel-type solution. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, Y.; Ohshima, H. Electrophoretic mobility of a water-in-oil droplet separately affected by the net charge and surface charge density. Langmuir 2022, 38, 4213–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, P.; Ohshima, H.; Gopmandal, P.P. Electrophoresis of dielectric and hydrophobic spherical fluid droplets possessing uniform surface charge density. Langmuir 2022, 38, 11421–11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mahapatra, P.; Ohshima, H.; Gopmandal, P.P. Dynamic electrophoresis of a hydrophobic and dielectric fluid droplet. Langmuir 2023, 39, 14139–14153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, J.; Su, J.; Chang, K.; Chang, A.; Chuang, L.; Lu, A.; Lee, R.; Lee, E. Electrophoresis of a dielectric droplet with constant surface charge density. Electrophoresis 2023, 44, 1810–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Ohshima, H.; Gopmandal, P.P. Electrophoresis of hydrophobic and polarizable liquid droplets in hydrogel medium. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 395, 123810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J. Roles of interfacial-exchange kinetics and interfacial-charge mobility on fluid-sphere electrophoresis. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1005, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xu, H.; Tu, L.; Ren, Y. Alternating-current induced-charge electrokinetic self-propulsion of metallodielectric Janus particles in confined microchannels within a wide frequency range. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 138, 184702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, X. Review of nonlinear electrokinetic flows in insulator-based dielectrophoresis: From induced charge to Joule heating effects. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Electrophoresis of a weakly charged oil drop in an electrolyte solution: Ion adsorption and Marangoni effects. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2025, 303, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Gel electrophoresis of an oil drop. Gels 2025, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohshima, H. Sedimentation potential in a dilute suspension of ion-adsorbed liquid drops under gravity: Marangoni effects and Onsager relation. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2025, 303, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Impact of hydrodynamic slip on the electrokinetics of an oil drop. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohshima, H. Dynamic Electrophoresis of an Oil Drop. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121407

Ohshima H. Dynamic Electrophoresis of an Oil Drop. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121407

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhshima, Hiroyuki. 2025. "Dynamic Electrophoresis of an Oil Drop" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121407

APA StyleOhshima, H. (2025). Dynamic Electrophoresis of an Oil Drop. Micromachines, 16(12), 1407. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121407