Dual Surfactant-Assisted Hydrothermal Engineering of Co3V2O8 Nanostructures for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

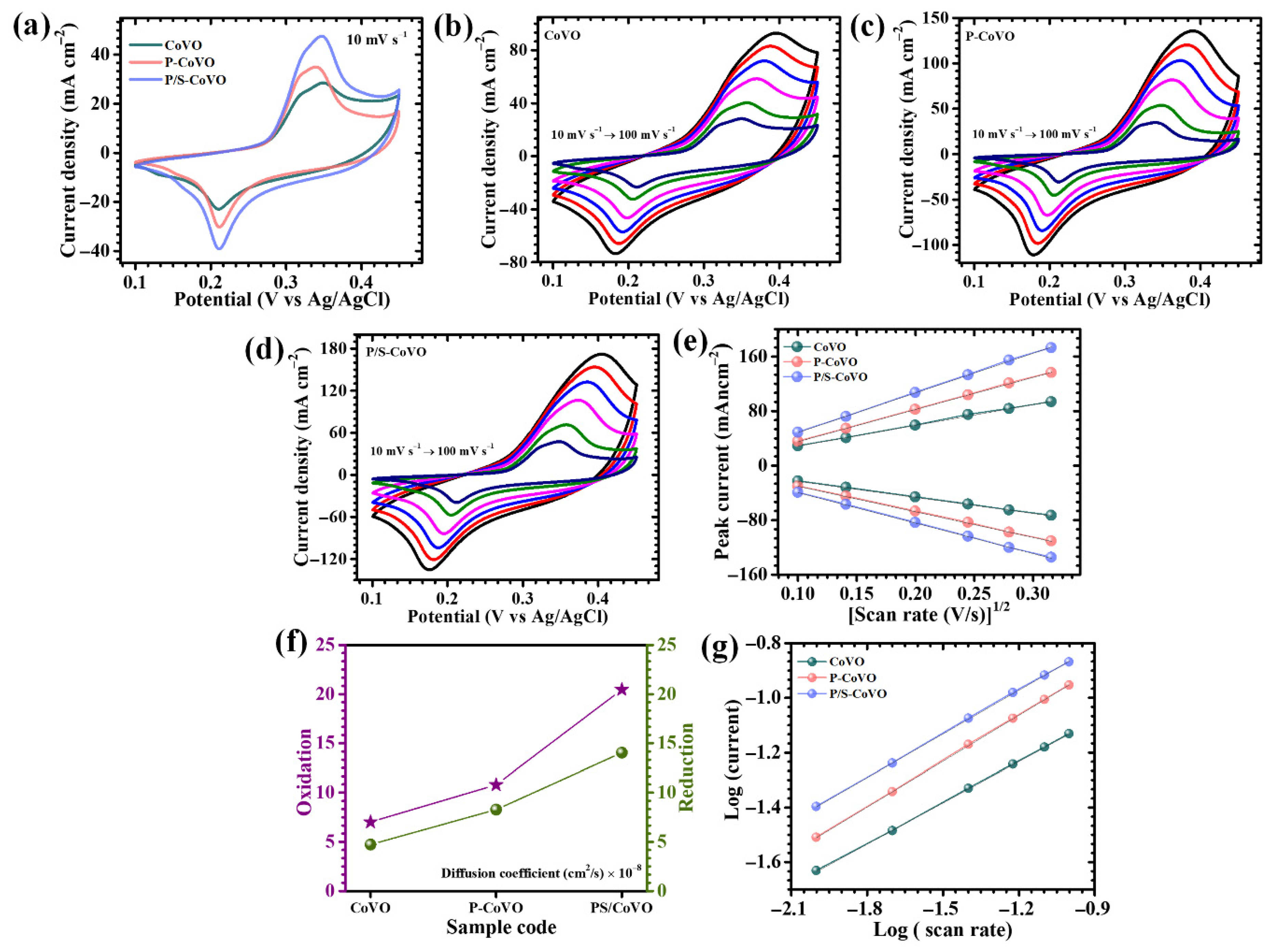

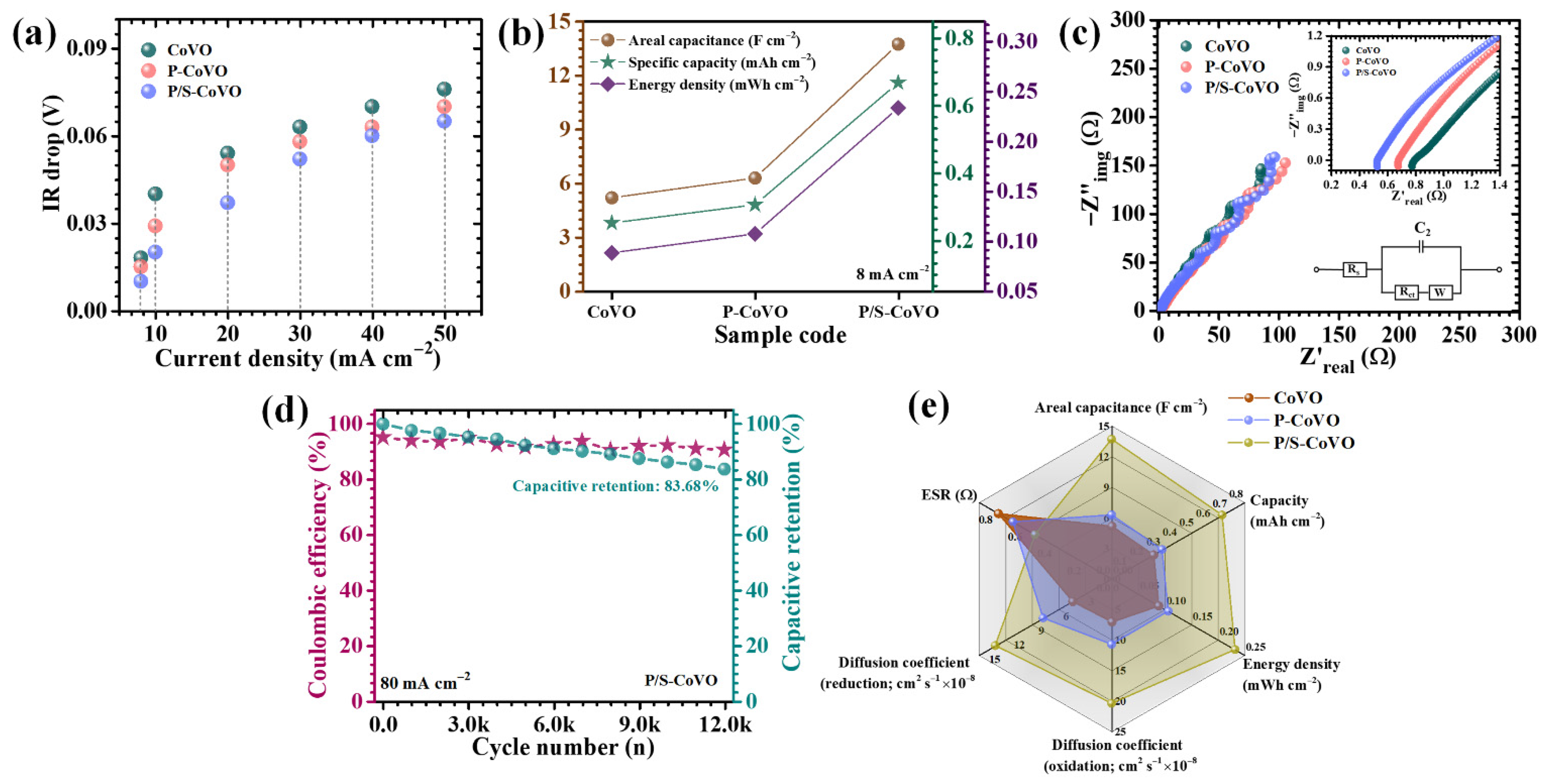

2.2. Synthesis of CoVO and Surfactant-Modified Variants

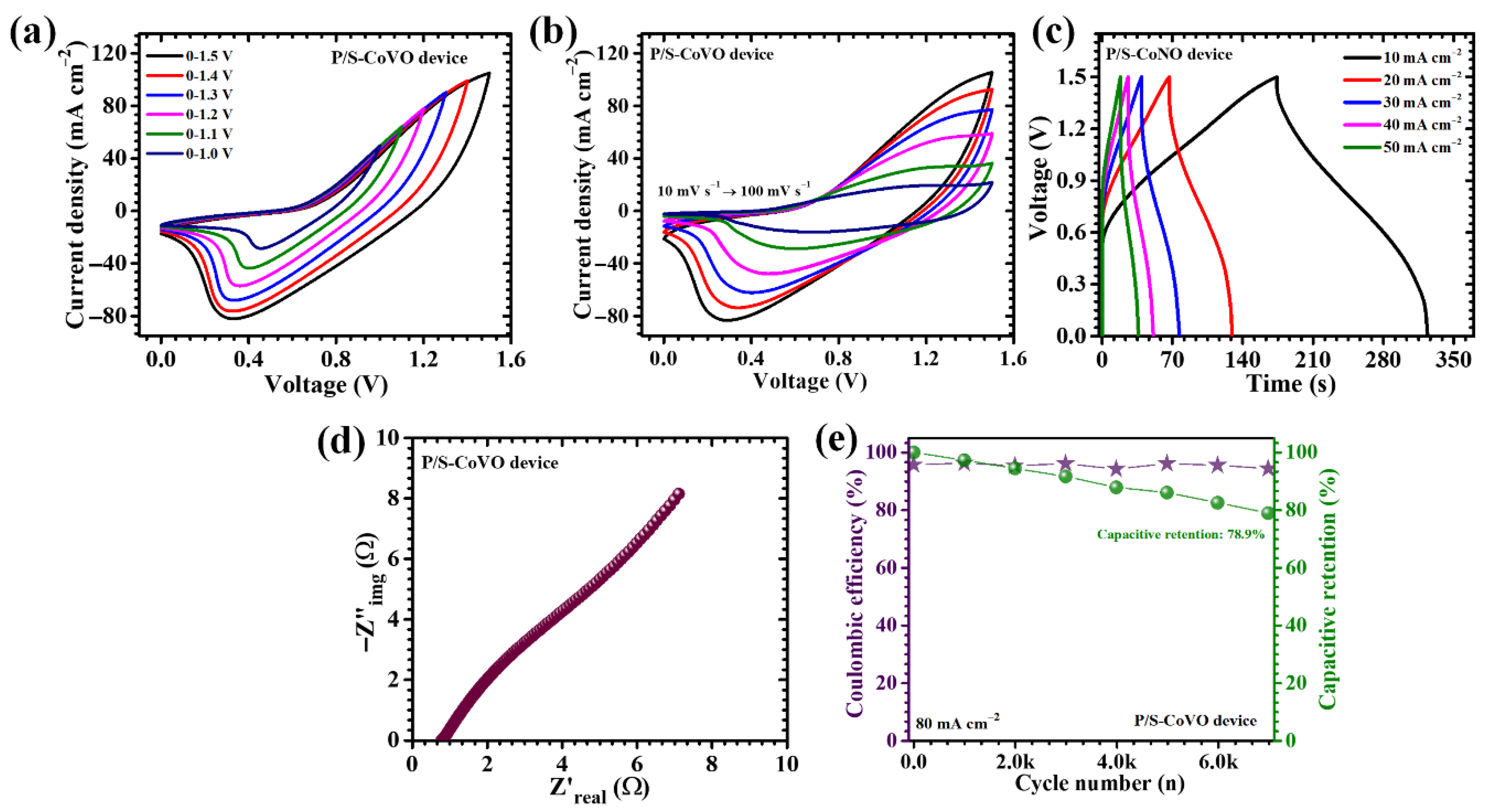

3. Sample Characterization and Electrochemical Measurements

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. X-Ray Diffraction Elucidation

4.2. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

4.3. Morphological and Elemental Composition

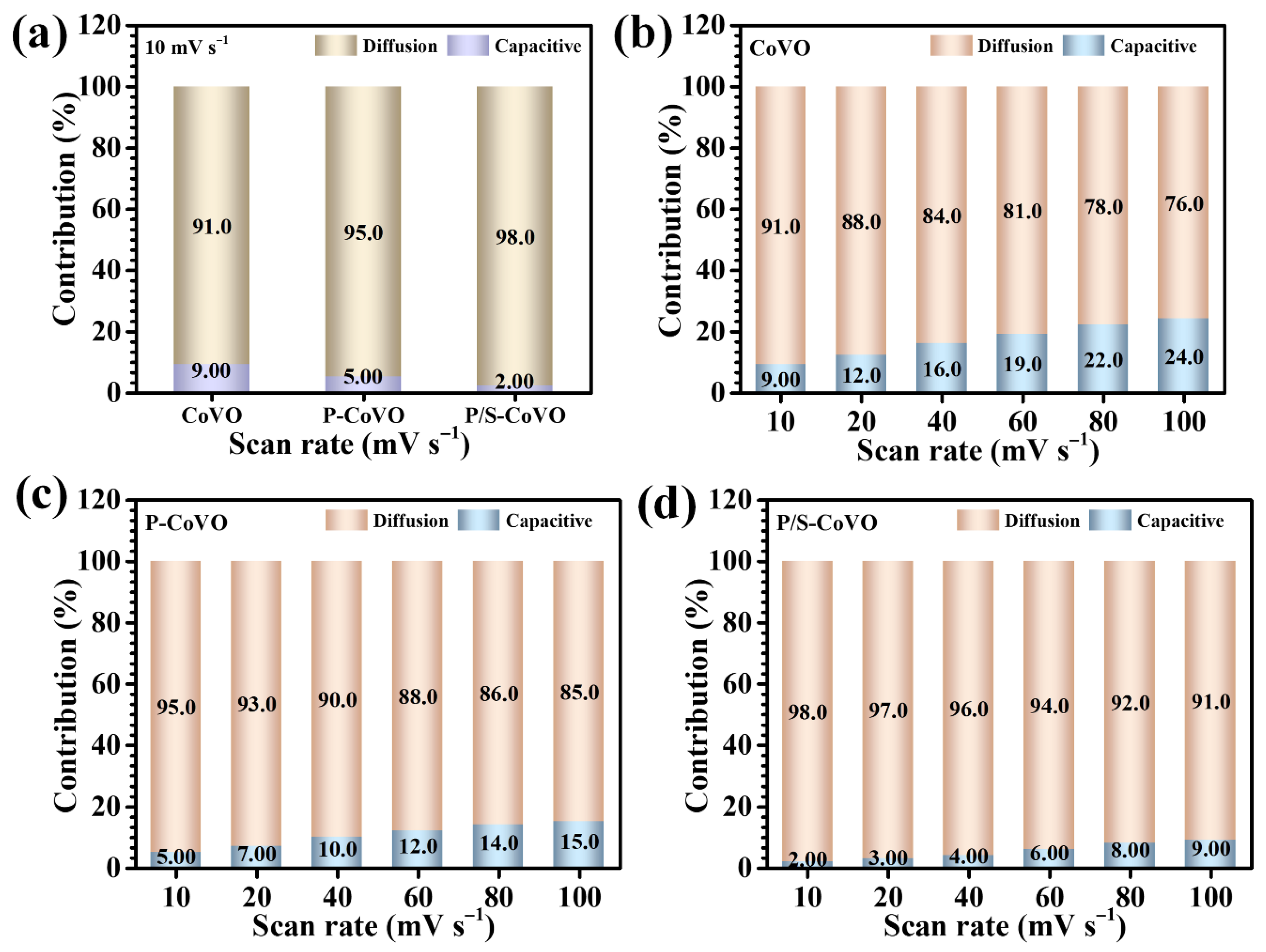

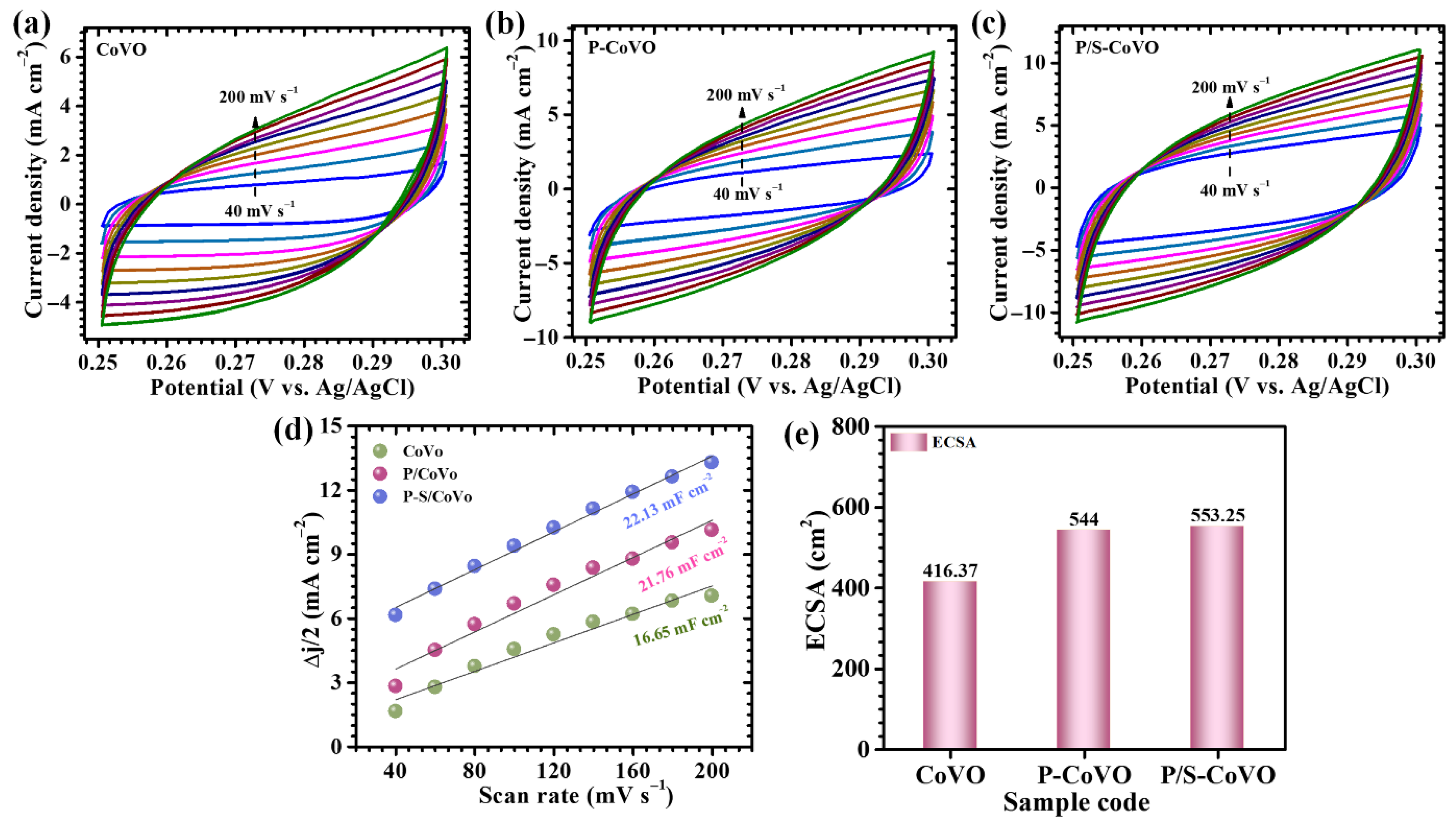

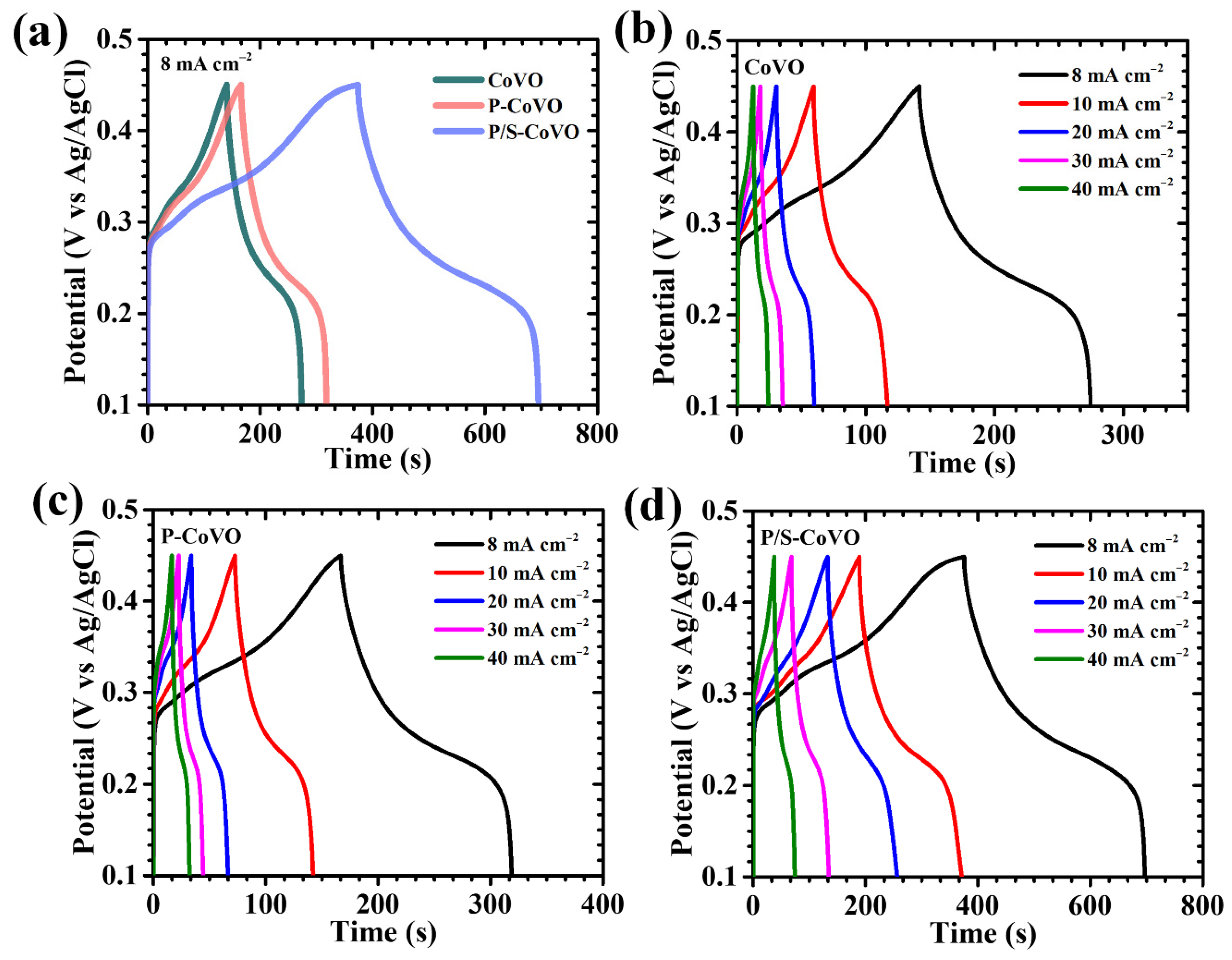

5. Electrochemical Analysis

6. Electrochemical Performance of Asymmetric Supercapacitor Device

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khaleel, M.; Yusupov, Z. Advancing Sustainable Energy Transitions: Insights on Finance, Policy, Infrastructure, and Demand-Side Integration. Unconv. Resour. 2026, 9, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzigeorgiou, N.G.; Theocharides, S.; Makrides, G.; Georghiou, G.E. A Review on Battery Energy Storage Systems: Applications, Developments, and Research Trends of Hybrid Installations in the End-User Sector. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Rui, X.; Bai, R.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.H.; Zhao, M.; Li, B.Q.; Zhang, X.; et al. Roadmap for Next-Generation Electrochemical Energy Storage Technologies: Secondary Batteries and Supercapacitors. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 30568–30687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid Khan, H.; Latif Ahmad, A. Supercapacitors: Overcoming Current Limitations and Charting the Course for next-Generation Energy Storage. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 141, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morankar, P.J.; Amate, R.U.; Teli, A.M.; Bhosale, M.K.; Beknalkar, S.A.; Jeon, C.-W. Architectonic Redox Interface Coupling in Bilayered NiFe2O4@Co3O4 Composites for Asymmetric Supercapacitive Energy Storage. J. Power Sources 2026, 661, 238690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amate, R.U.; Morankar, P.J.; Teli, A.M.; Bhosale, M.K.; Ahir, N.A.; Jeon, C.W. Interface-Centric Strategies in Nb2O5/MoS2 Heterostructure: Leveraging Synergistic Potential for Dual-Function Electrochromic Energy Storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 161962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Al Mahmud, A.; Pandiyarajan, S.; Singh, K.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Morankar, P.J.; Hussain, S.; Rosaiah, P.; Khan, M.Z.; Ajmal, Z.; et al. Practicality of MXenes: Recent Trends, Considerations, and Future Aspects in Supercapacitors. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 55, 101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, H.; Valio, J.; Suominen, P.; Tynjälä, P.; Lassi, U. Advancements in Cathode Technology, Recycling Strategies, and Market Dynamics: A Comprehensive Review of Sodium Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, X. NiCo2O4-Based Materials for Electrochemical Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 14759–14772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Seifi, M.; Moghadam, M.T.T.; Askari, M.B.; Varma, R.S. High-Capacity MnCo2O4/NiCo2O4 as Electrode Materials for Electrochemical Supercapacitors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 174, 111176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruchamy, K.; Balasankar, A.; Ramasundaram, S.; Oh, T.H. Recent Design and Synthesis Strategies for High-Performance Supercapacitors Utilizing ZnCo2O4-Based Electrode Materials. Energies 2023, 16, 5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qin, Y.; Weng, D.; Xiao, Q.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Wei, F.; Lu, Y. Design and Synthesis of Hierarchical Nanowire Composites for Electrochemical Energy Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 3420–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraveji, S.; Fotouhi, L.; Shahrokhian, S.; Zirak, M. Boosting Energy Storage Performance of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 with Core-Shell Structure as an Efficient Positive Electrode for Fabrication of High-Performance Hybrid Supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isacfranklin, M.; Deepika, C.; Ravi, G.; Yuvakkumar, R.; Velauthapillai, D.; Saravanakumar, B. Nickel, Bismuth, and Cobalt Vanadium Oxides for Supercapacitor Applications. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 28206–28210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasi, S.E.; Ranjithkumar, R.; Devendran, P.; Krishnakumar, M.; Arivarasan, A. Studies on Electrochemical Mechanism of Nanostructured Cobalt Vanadate Electrode Material for Pseudocapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Du, M.; Demir, M.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Gu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J. In-Situ Formation of Morphology-Controlled Cobalt Vanadate on CoO Urchin-like Microspheres as Asymmetric Supercapacitor Electrode. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 958, 170489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jiang, J.; Tian, H.; Niu, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, C. A Facile Method to Synthesize CoV2O6 as a High-Performance Supercapacitor Cathode. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 9475–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Chai, H.; Wang, Y.; Jia, D.; Cao, Y.; Liu, A. 3D Porous Hydrated Cobalt Pyrovanadate Microflowers with Excellent Cycling Stability as Cathode Materials for Asymmetric Supercapacitor. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 469, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Sari, F.N.I.; Ting, J.M. 3D Hierarchical Cobalt Vanadate Nanosheet Arrays on Ni Foam Coupled with Redox Additive for Enhanced Supercapacitor Performance. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 29170–29176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Rajkumar, P.; Radhika, G.; Iyer, M.S.; Manigandan, R.; Rajaiah, D.K.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Raman, S.; Marimuthu, S.; Kim, J. High Performance and Enhanced Stability of Mn–Co3V2O8 Coral-like Structure for Supercapacitor Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 9419–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerthana, M.; Archana, J.; Senthil Kumar, E.; Navaneethan, M. Synergistic Enhancement of Electrochemical Performance in Co3O4/CuO/RGO Heterostructures Composite for High-Energy, High-Rate Supercapattery Devices. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 1212–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T. A Facile Green Synthesis of Porous Hexagonal Cobalt Pyrovanadate Electrode for Supercapacitors by Deep Eutectic Solvent. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 892, 162205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdluli, P.S.; Sosibo, N.M.; Mashazi, P.N.; Nyokong, T.; Tshikhudo, R.T.; Skepu, A.; Van Der Lingen, E. Selective Adsorption of PVP on the Surface of Silver Nanoparticles: A Molecular Dynamics Study. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 1004, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Q.; Farooq, U.; Chen, W.; Miao, R.; Qi, Z. Anionic Surfactant-Assisted the Transport of Carbon Dots through Saturated Soil and Its Variation with Aqueous Chemistry. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 644, 128860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morankar, P.J.; Amate, R.U.; Teli, A.M.; Chavan, G.T.; Beknalkar, S.A.; Dalavi, D.S.; Ahir, N.A.; Jeon, C.W. Surfactant Integrated Nanoarchitectonics for Controlled Morphology and Enhanced Functionality of Tungsten Oxide Thin Films in Electrochromic Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safo, I.A.; Werheid, M.; Dosche, C.; Oezaslan, M. The Role of Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as a Capping and Structure-Directing Agent in the Formation of Pt Nanocubes. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 3095–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poolakkandy, R.R.; Menamparambath, M.M. Soft-Template-Assisted Synthesis: A Promising Approach for the Fabrication of Transition Metal Oxides. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 5015–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, A.; Farrukh, M.A.; Khaleeq-Ur-Rahman, M.; Adnan, R. Micelle-Assisted Synthesis of Al2O3·CaO Nanocatalyst: Optical Properties and Their Applications in Photodegradation of 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 641420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, T.; Pang, H. Cobalt Vanadium Oxide Thin Nanoplates: Primary Electrochemical Capacitor Application. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.B.; Kong, L.B.; Ma, X.J.; Luo, Y.C.; Kang, L. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Three-Dimensional Co3O4/Co3(VO4)2 Hybrid Nanorods on Nickel Foam as Self-Supported Electrodes for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2014, 269, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, S.S.; Bhosale, S.B.; Patil, S.S.; Ransing, A.; Parale, V.G.; Lokhande, C.D.; Park, H.H.; Patil, U.M. Chemical Synthesis of Binder-Free Nanosheet-like Cobalt Vanadium Oxide Thin Film Electrodes for Hybrid Supercapacitor Devices. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 5467–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczkur, K.M.; Mourdikoudis, S.; Polavarapu, L.; Skrabalak, S.E. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in Nanoparticle Synthesis. Dalt. Trans. 2015, 44, 17883–17905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi-Derazkola, S.; Zinatloo-Ajabshir, S.; Salavati-Niasari, M. New Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Assisted Preparation of Nd2O3 Nanostructures via a Simple Route. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 56666–56676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Panda, P.; Barman, S. Synthesis of a Co3V2O8/CNx Hybrid Nanocomposite as an Efficient Electrode Material for Supercapacitors. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 5897–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, S.S.; Kadam, R.A.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Kadam, S.L.; Teli, A.M.; Al-Kahtani, A.A.; Radhalayam, D.; Shin, D.K.; Yewale, M.A. Transitioning from Microballs to Microrods via Time Interval: Shaping Cobalt Vanadium Oxide for Use in Energy Storage Devices. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 428, 127513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liardet, L.; Hu, X. Amorphous Cobalt Vanadium Oxide as a Highly Active Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Evolution. ACS Catal. 2017, 8, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Dong, H.; Jia, D.; Zhou, W. Low-Cost Synthesis of Hierarchical Co3V2O8 Microspheres as High-Performance Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, M.A.; Saeed, A.H.; Sharif, M.; Rehman, A. Direct Deposition of Amorphous Cobalt–Vanadium Mixed Oxide Films for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12671–12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarabelli, L.; Sun, M.; Zhuo, X.; Yoo, S.; Millstone, J.E.; Jones, M.R.; Liz-Marzán, L.M. Plate-Like Colloidal Metal Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 3493–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.S.; Betty, C.A.; Bhosale, P.N.; Patil, P.S.; Hong, C.K. From Nanocorals to Nanorods to Nanoflowers Nanoarchitecture for Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells at Relatively Low Film Thickness: All Hydrothermal Process. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavolu, M.R.; Muralee Gopi, C.V.V.; Prabu, S.; Ullapu, P.R.; Jung, J.H.; Joo, S.W.; Ramesh, R. Hierarchical Nanoporous NiCoN Nanoflowers with Highly Rough Surface Electrode Material for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 4619–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Xu, C.; Liu, H. MXene-Driven in Situ Construction of Hollow Core-Shelled Co3V2O8@Ti3C2Tx Nanospheres for High-Performance All-Solid-State Asymmetric Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 24896–24904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amate, R.U.; Morankar, P.J.; Teli, A.M.; Beknalkar, S.A.; Chavan, G.T.; Ahir, N.A.; Dalavi, D.S.; Jeon, C.W. Versatile Electrochromic Energy Storage Smart Window Utilizing Surfactant-Assisted Niobium Oxide Thin Films. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Polleux, J.; Lim, J.; Dunn, B. Pseudocapacitive Contributions to Electrochemical Energy Storage in TiO2 (Anatase) Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 14925–14931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Lamiel, C.; Mohamed, S.G.; Vijayakumar, S.; Ali, A.; Shim, J.J. Controlled Synthesis and Growth Mechanism of Zinc Cobalt Sulfide Rods on Ni-Foam for High-Performance Supercapacitors. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 71, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Gai, S.; He, F.; Niu, N.; Gao, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, P. A Sandwich-Type Three-Dimensional Layered Double Hydroxide Nanosheet Array/Graphene Composite: Fabrication and High Supercapacitor Performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 2, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkhanna, G.; Umeshbabu, E.; Ranga Rao, G. Charge Storage, Electrocatalytic and Sensing Activities of Nest-like Nanostructured Co3O4. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 487, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawade, A.K.; Tayade, S.N.; Dubal, D.P.; Mali, S.S.; Hong, C.K.; Sharma, K.K.K. Enhanced Supercapacitor Performance through Synergistic Electrode Design: Reduced Graphene Oxide-Polythiophene (RGO-PTs) Nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 492, 151843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Z.; Su, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, L. One-Step Hydrothermal Synthesis of Tb-Doped MnO2 Nanosheet@nanowire Homostructures for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 708, 163767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboraia, A.M.; Sharaf, I.M.; Alradaddi, S.; Ben Gouider Trabelsi, A.; Alkallas, F.H. Advanced Supercapacitors: Benefit from the Electrode Material Cubic-ZrO2 by Doping with Gd. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 714, 417519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kang, L.; Jun, S.C. Challenges and Strategies toward Cathode Materials for Rechargeable Potassium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, S.K.; Rao, G.R. Ultralayered Co3O4 for High-Performance Supercapacitor Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 15646–15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.; Raut, S.D.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Algadi, H.; Albargi, H.; Alsaiari, M.A.; Akhtar, M.S.; Qamar, M.; Baskoutas, S. Perforated Co3O4 Nanosheets as High-Performing Supercapacitor Material. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 389, 138661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zeng, G.; Liu, Z.; Tang, L.; Shao, B.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.; et al. Surfactant-Assisted Synthesis of Photocatalysts: Mechanism, Synthesis, Recent Advances and Environmental Application. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Gao, F.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; You, H.; Du, Y. A Review of the Role and Mechanism of Surfactants in the Morphology Control of Metal Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 3895–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytürk, S.E.Y.; Çıtak, A.; Aydın, E.C.; Durukan, M.B. Synthesis of Heterostructured Nanocomposites as Supercapacitor Electrodes and Investigation of Their Electrochemical Properties. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 472, 143379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.A.; Yewale, M.A.; Teli, A.M.; Annu; Nakate, U.T.; Kumar, V.; Kadam, S.L.; Shin, D.K. Bimetallic Co3V2O8 Microstructure: A Versatile Bifunctional Electrode for Supercapacitor and Electrocatalysis Applications. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 41, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renani, A.S.; Momeni, M.M.; Aydisheh, H.M.; Lee, B.K. New Photoelectrodes Based on Bismuth Vanadate-V2O5@TiNT for Photo-Rechargeable Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code | Diffusion Coefficient (cm2/s) × 10−8 | b-Value | ESR (R1) (Ω) | Rct (R2) (Ω) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation | Reduction | ||||

| CoVO | 7.02 | 4.72 | 0.56 | 0.802 | 12.89 |

| P-CoVO | 10.8 | 8.28 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 6.042 |

| P/S-CoVO | 20.46 | 14.05 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 2.134 |

| Sample Code | I (mA cm−2) | Areal Capacitance CA (F cm−2) | Capacity (mAh cm−2) | Energy Density ED (mWh cm−2) | Power Density PD (mW cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoVO | 8 | 5.172 | 0.251 | 0.088 | 2.37 |

| 10 | 2.449 | 0.119 | 0.042 | 2.62 | |

| 20 | 2.416 | 0.117 | 0.041 | 5.07 | |

| 30 | 2.057 | 0.100 | 0.035 | 7.41 | |

| 40 | 1.763 | 0.086 | 0.030 | 9.31 | |

| P-CoVO | 8 | 6.269 | 0.305 | 0.107 | 2.49 |

| 10 | 3.298 | 0.160 | 0.056 | 2.89 | |

| 20 | 2.612 | 0.127 | 0.044 | 4.85 | |

| 30 | 2.449 | 0.119 | 0.042 | 7.14 | |

| 40 | 2.155 | 0.105 | 0.037 | 8.25 | |

| P/S-CoVO | 8 | 13.714 | 0.667 | 0.233 | 2.61 |

| 10 | 10.449 | 0.508 | 0.178 | 2.54 | |

| 20 | 7.837 | 0.381 | 0.133 | 5.20 | |

| 30 | 7.510 | 0.365 | 0.128 | 7.16 | |

| 40 | 5.224 | 0.254 | 0.089 | 8.89 |

| Material | Areal Capacitance | Current | Stability | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co3V2O8 | 3.76 F cm−2 | 1 mA cm2 | - | [56] |

| Co3V2O8 | 3.5 F cm−2 | 1 mA cm2 | 87% retention (5000 cycles) | [57] |

| Ni, Bi, Co-Co3V2O8 | 285.65 F g−1 | - | 83.64% retention (5000 cycles) | [14] |

| Co3V2O8/CNx composite | 1.23 F cm−2 | 1 mA | 87% retention (4000 cycles) | [34] |

| CO3V2O8 | 790 F g−1 | 1 A g−1 | 90.1% retention (10000 cycles) | [15] |

| Bismuth vanadate–V2O5 | 0.288 F cm−2 | 0.12 mA cm−2 | 99.7% retention (4000 cycles) | [58] |

| P/S-CoVO | 13.714 F cm−2 | 8 mA cm−2 | 83.68% retention (12,000 cycles) | This work |

| Sample Code | I (mA) | CA (F cm−2) | C (mAh cm−2) | ED (mWh cm−2) | PD (mW cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P/S-CoVO device | 10 | 0.369 | 0.077 | 0.115 | 1.37 |

| 20 | 0.276 | 0.057 | 0.086 | 2.50 | |

| 30 | 0.197 | 0.041 | 0.062 | 2.92 | |

| 40 | 0.142 | 0.030 | 0.044 | 3.20 | |

| 50 | 0.102 | 0.021 | 0.032 | 3.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morankar, P.J.; Patil, A.A.; Teli, A.; Jeon, C.-W. Dual Surfactant-Assisted Hydrothermal Engineering of Co3V2O8 Nanostructures for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121334

Morankar PJ, Patil AA, Teli A, Jeon C-W. Dual Surfactant-Assisted Hydrothermal Engineering of Co3V2O8 Nanostructures for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121334

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorankar, Pritam J., Aditya A. Patil, Aviraj Teli, and Chan-Wook Jeon. 2025. "Dual Surfactant-Assisted Hydrothermal Engineering of Co3V2O8 Nanostructures for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121334

APA StyleMorankar, P. J., Patil, A. A., Teli, A., & Jeon, C.-W. (2025). Dual Surfactant-Assisted Hydrothermal Engineering of Co3V2O8 Nanostructures for High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Micromachines, 16(12), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121334