Active–Passive Vibration Control of Cantilever Beam Based on Magnetic Spring with Negative Stiffness and Piezoelectric Actuator

Abstract

1. Introduction

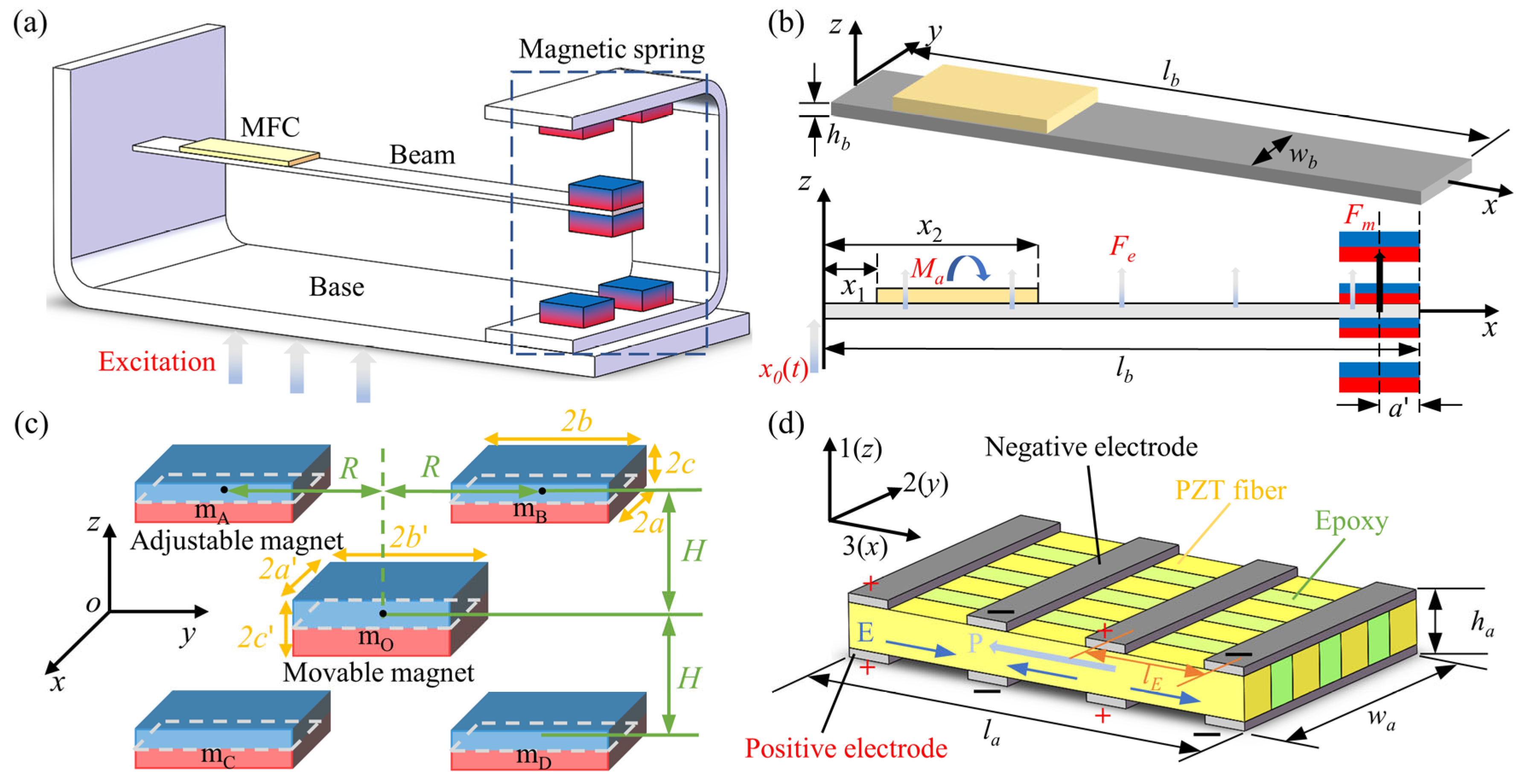

2. Structural Description and Modeling of MTPCBS

2.1. Structural Description

2.2. Dynamic Modeling of the MTPCBS

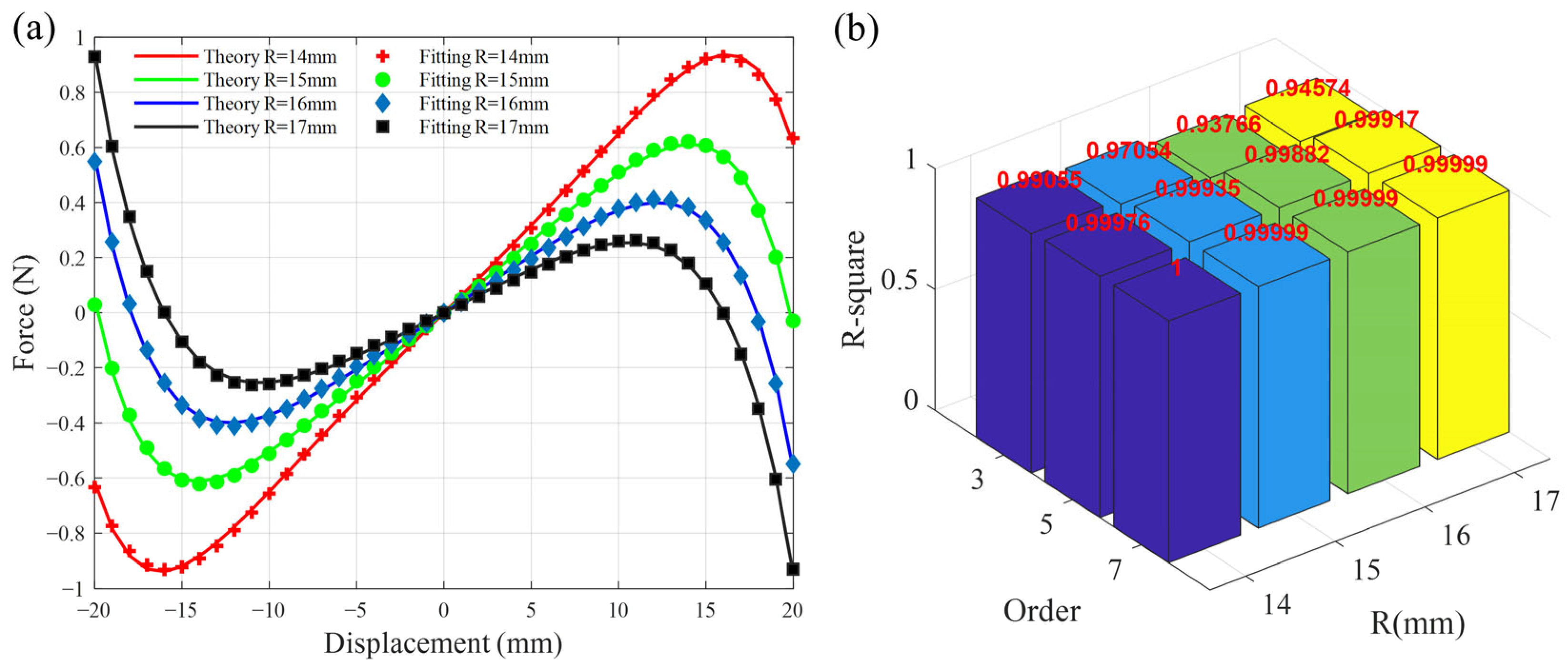

2.3. Modeling of NSMS

2.4. Modeling of MFC

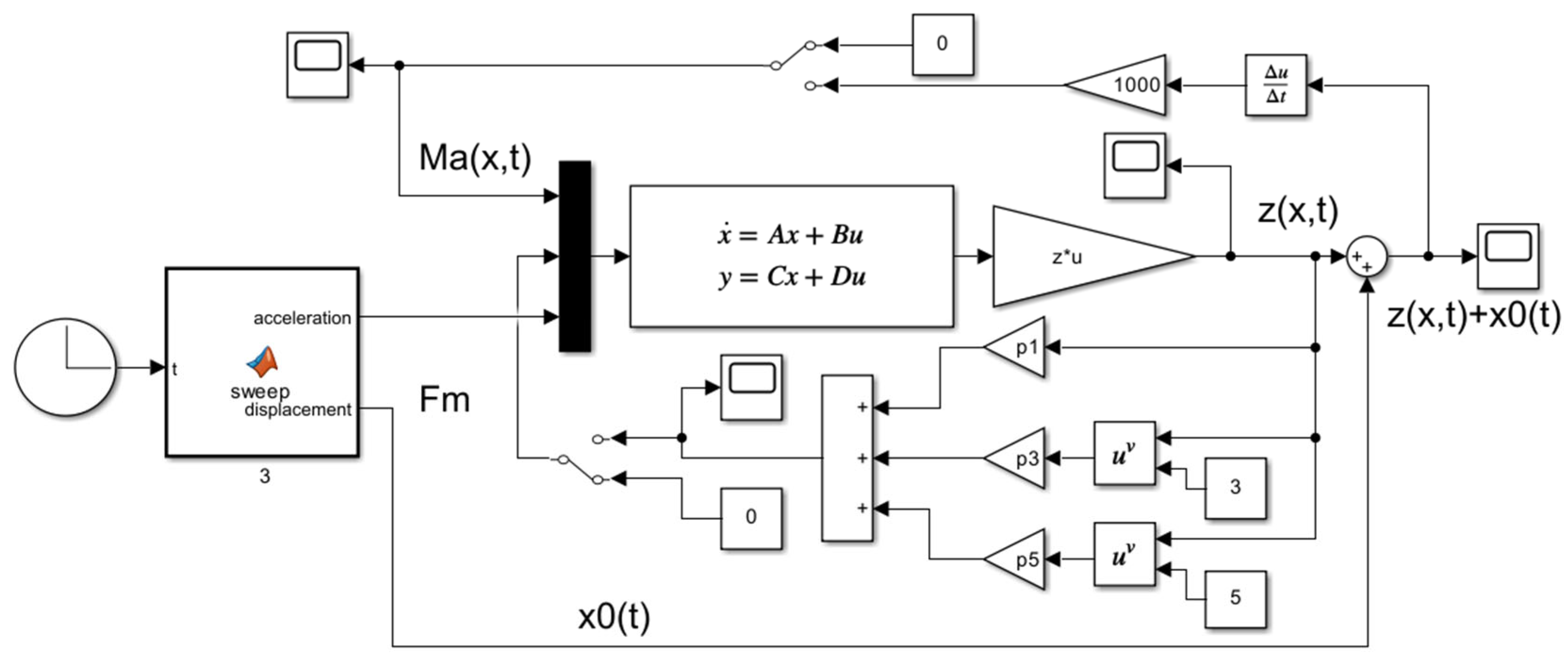

2.5. State Space Representation

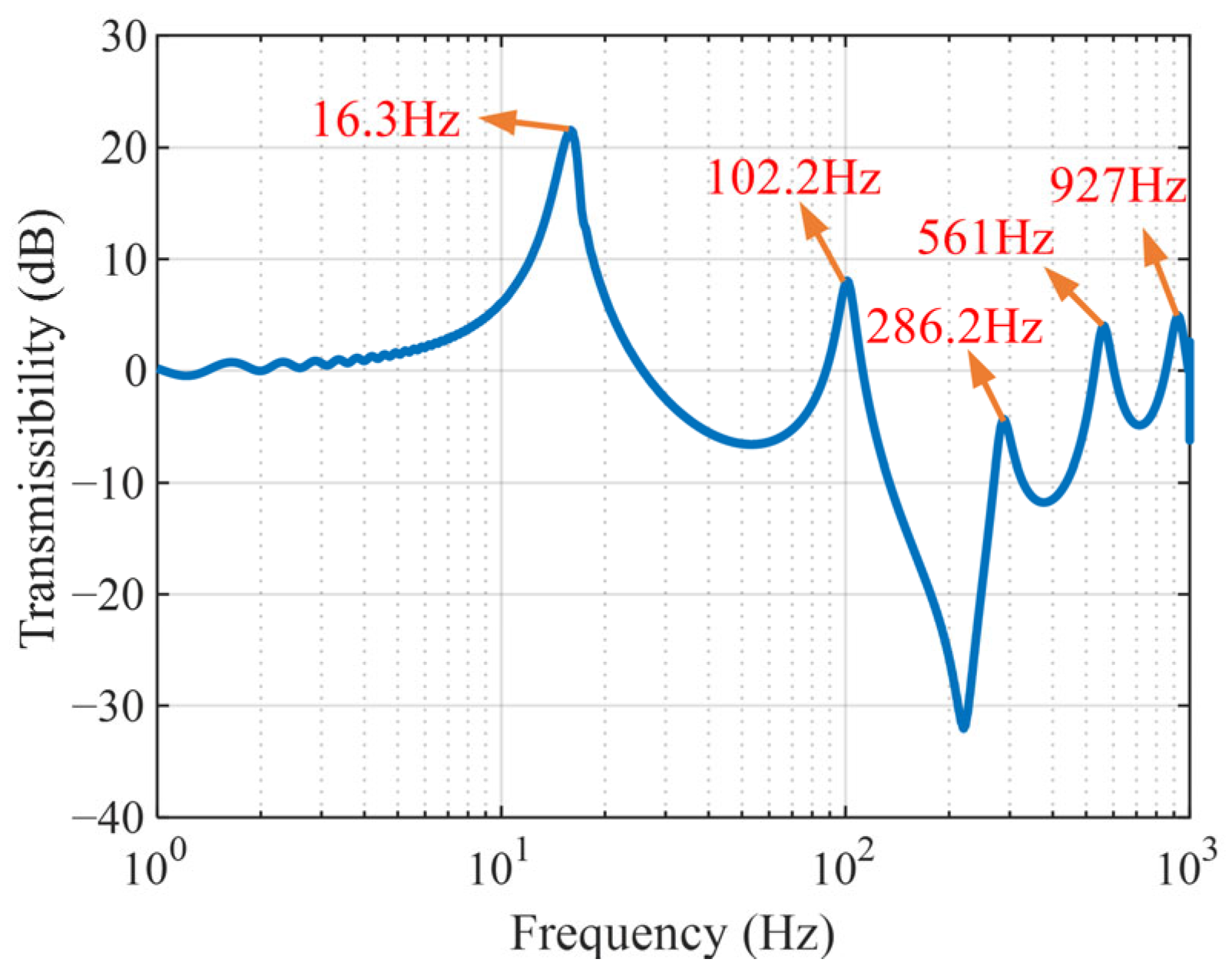

2.6. Displacement Transmissibility

2.7. Control Strategy

3. Numerical Simulations

3.1. Simulation Model

3.2. Effect of Passive Control

3.3. Effect of Active Control

4. Experimental Verification

4.1. Experimental Setup

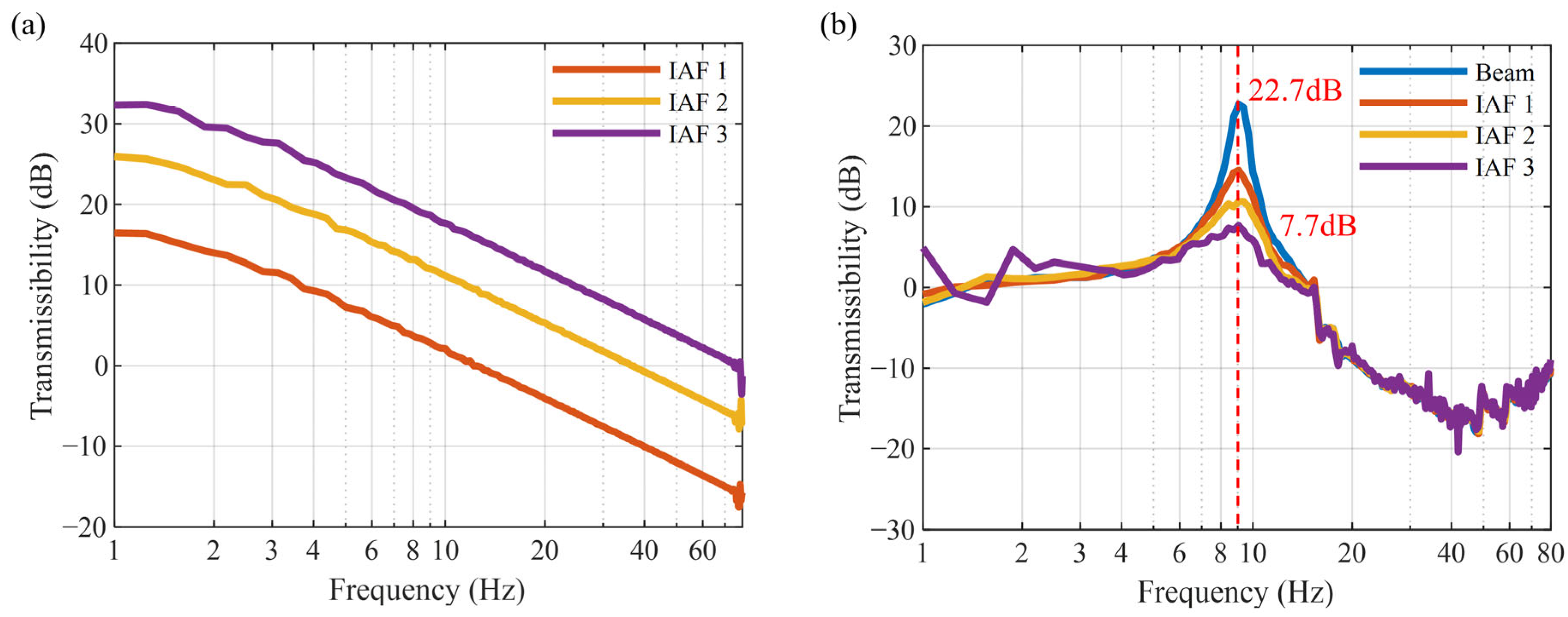

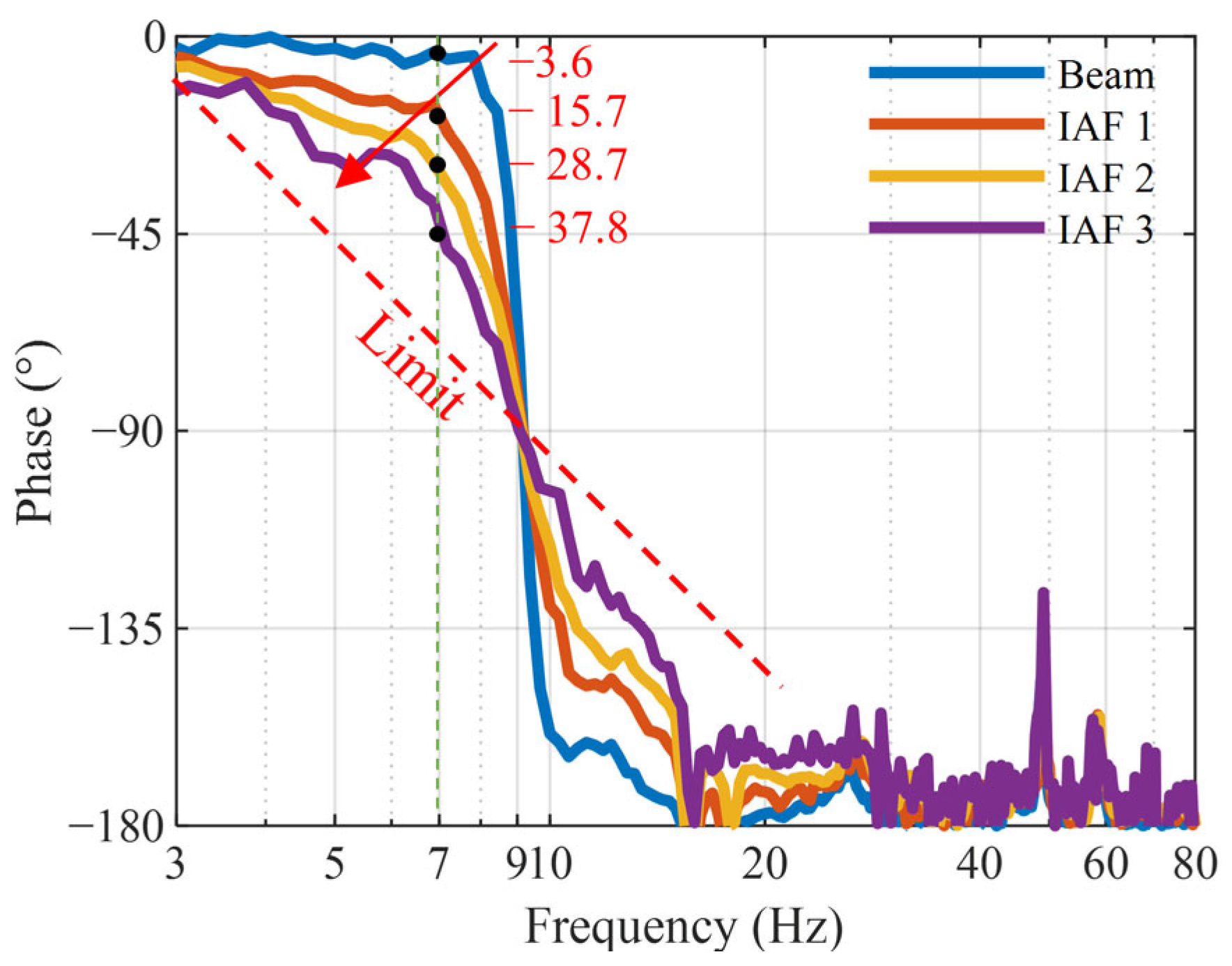

4.2. Verification of the Parallel of Positive and Negative Stiffness

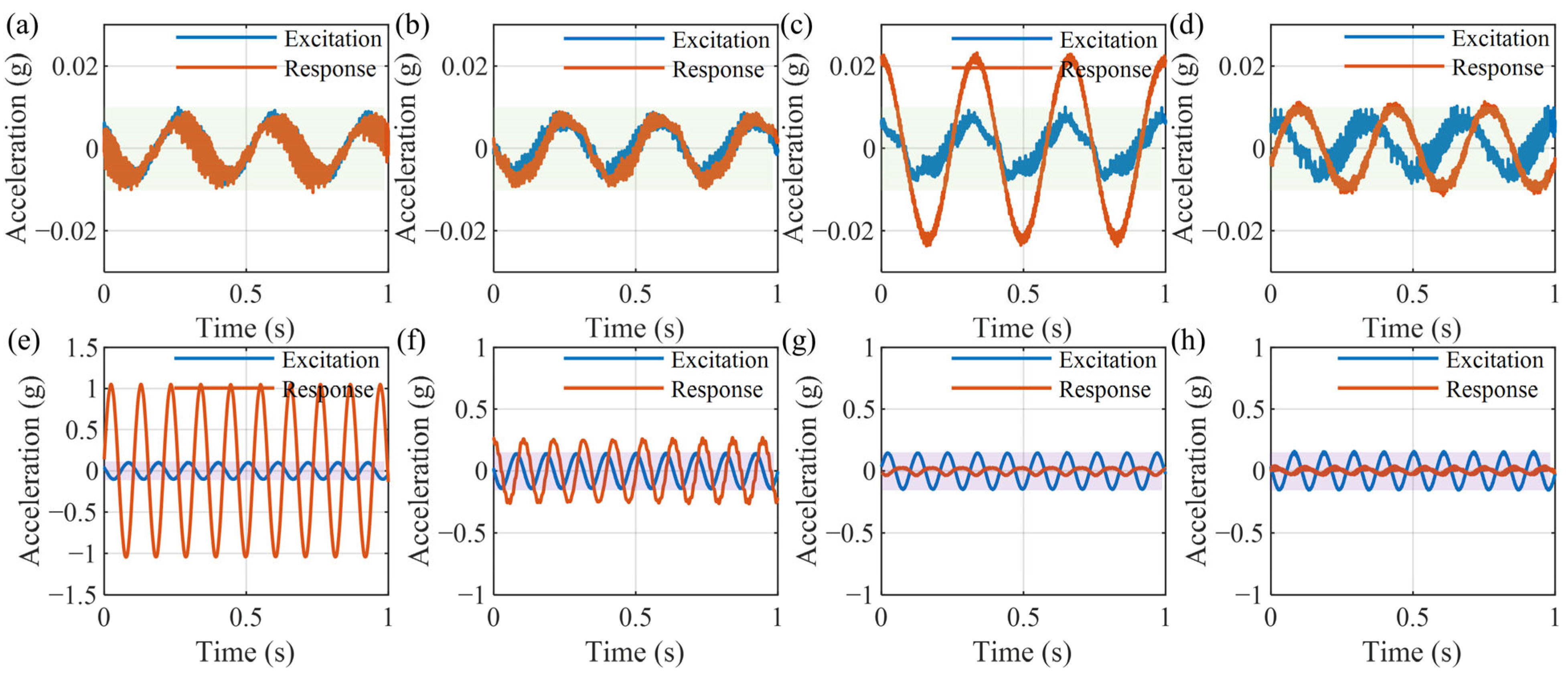

4.3. Verification of Active Vibration Control

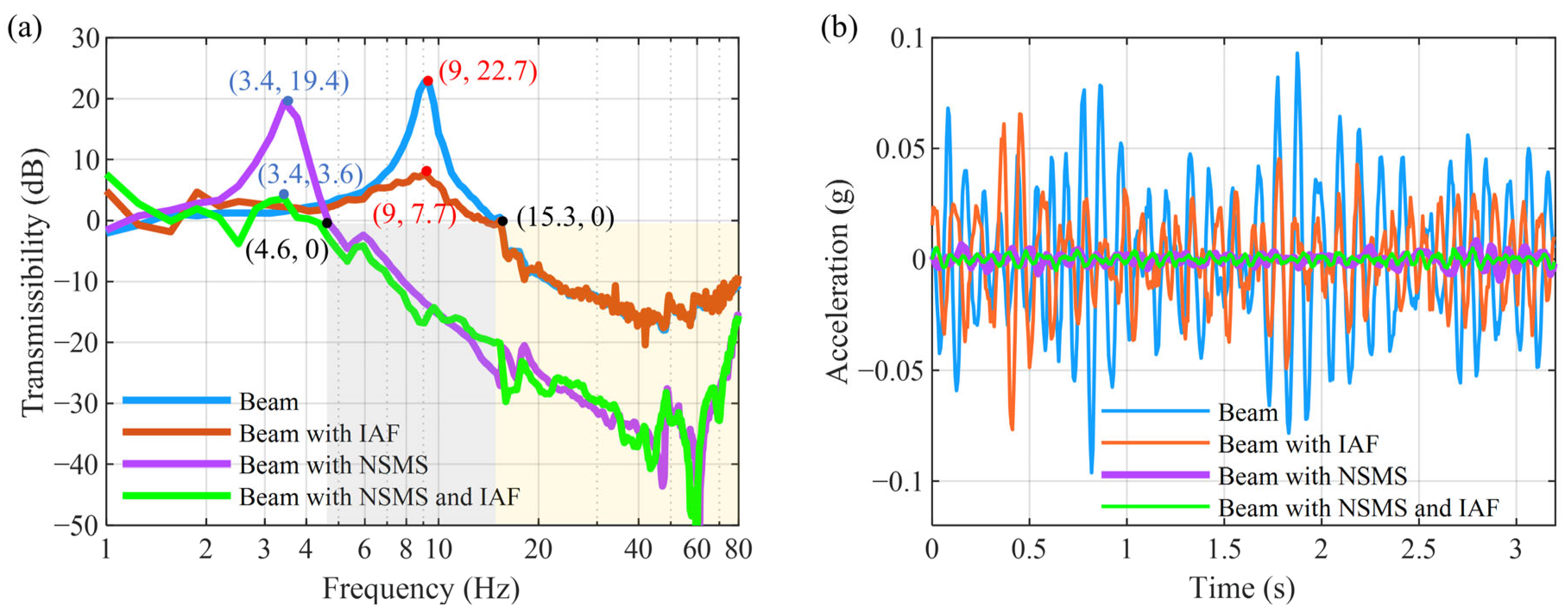

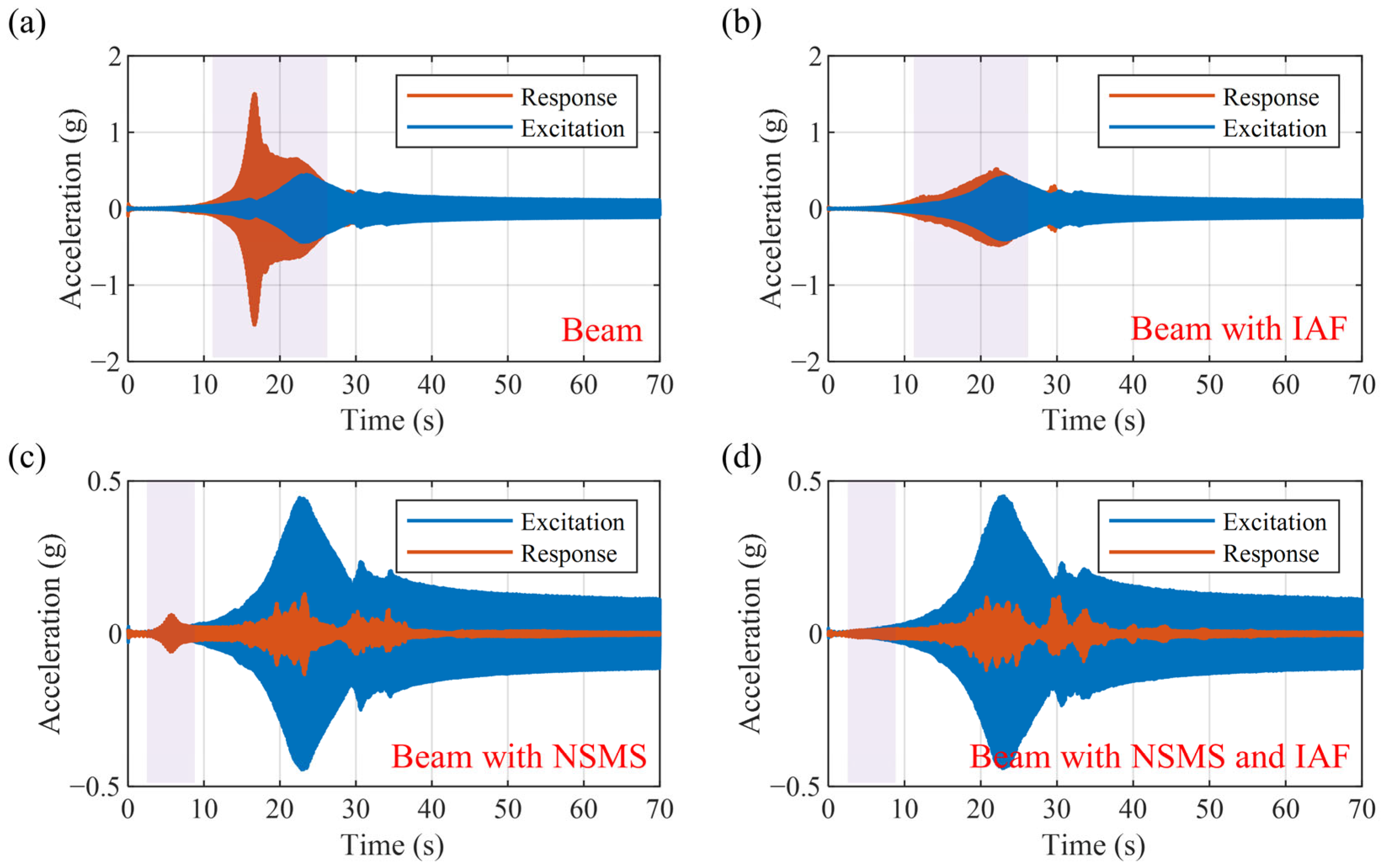

4.4. Comparison of Vibration Isolation Performance

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- By adjusting the magnet distance, a QZS structure can be achieved. The natural frequency of the MTPCBS is reduced from 9 Hz to 3.4 Hz, broadening the vibration suppression bandwidth. Under identical excitation conditions, the RMS vibration amplitude decreased from 0.03 g to 2.6 × 10−3 g, corresponding to an improvement in vibration attenuation from a 50% amplification to an 87% reduction.

- (b)

- With the implementation of active skyhook damping control, the resonance peak was reduced from 19.4 dB to 3.6 dB, and the RMS amplitude reached 1.77 × 10−3 g, achieving a vibration attenuation rate of 91%. The proposed active–passive vibration control method enhances the low-frequency vibration suppression capacity of the beam, offering a viable strategy for attenuating low-frequency vibrations in beam-type structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, Z.; Zhao, X.; Fan, W.; Gao, H.; Liu, Q.; Yong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K. A Two-Dimensional Cantilever Beam Vibration Sensor Based on Fiber Bragg Grating. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2021, 61, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, A.I.; Mohiuddin, M.; Ahmed, R.; Meade, D.; Akter, K.; Ahmed, H. Harnessing Vibrations: A Review on Structural Architecture and Design Ideology of the Cantilever Beam Based Piezoelectric Energy Harvesters. Appl. Energy 2025, 396, 126286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, P. Experimental Study of a Broadband Vibration Energy Harvester Based on Orthogonal Magnetically Coupled Double Cantilever Beam. Micromachines 2025, 16, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.; Maspero, F.; Esposito, A.; Afifi, T.A.; Riani, M.; Gattere, G.; Di Matteo, A.; Corigliano, A.; Ardito, R. Characterization of AlN in MEMS: Synergistic Use of Dynamic Testing, Static Profilometry, and an Enhanced Reduced-Order Model. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2025, 115, 105834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y. Design, Fabrication, and Characterization of a Piezoelectric Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer with a Suspended Cantilever Beam-like Structure with Enhanced SPL for Air Detection Applications. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Z.; Hao, R.; Sun, T. Modelling and Semi-Active Vibration Control for Spacecraft Solar Panels Equipped with Adjustable-Stiffness Magnetic Joints. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 165, 110453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayastha, S.; Katupitiya, J.; Pearce, G.; Rao, A. Comparative Study of Post-Impact Motion Control of a Flexible Arm Space Robot. Eur. J. Control 2023, 69, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, M.G.; Fleming, A.J.; Yong, Y.K. Active Atomic Force Microscope Cantilevers with Integrated Device Layer Piezoresistive Sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 319, 112519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jin, J.; Chen, Z. Thermo-Flexible Coupled Modeling and Active Control of Thermally Induced Vibrations for a Flexible Plate. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 211, 113092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.G.; Chi, W.C.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.Q. Three-Dimensional Vibration Suppression of Flexible Beams under Multi-Directional Excitations via Piezoelectric Actuators: Theoretical and Experimental Investigations. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 129, 1039–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y. Experiment and Simulation Research on the Vibration Reduction of a Dual-Beam System Equipped with a Wire-Type Coupling Nonlinear Energy Sink. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 237, 113148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Guo, X. Low-Frequency Vibration Suppression of Meta-Beam with Softening Nonlinearity. Appl. Math. Mech. 2025, 46, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisamudhin, K.M.; Acharya, A.; Jain, A.; DasGupta, A. Vibration and Damping Characteristics of 3D-Printed Lattice Beams. Mech. Mater. 2025, 210, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, G. Nonlinear Forced Vibration and Stability Analysis of a Rotating Three-Dimensional Cantilever Beam with Variable Cross-Section. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 211, 113104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Dai, W.; Zhu, C.; Li, R.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, J. Modelling and Nonlinear Analysis of Frictional Jointed Beams with Inerter-Based Dynamic Vibration Absorber. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 145, 116143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; An, Y.; Yang, X.; Hu, N.; Ma, L.; Peng, Y.; Wang, B. Broadband Multifrequency Vibration Attenuation of an Acoustic Metamaterial Beam with Two-Degree-of-Freedom Nonlinear Bistable Absorbers. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 212, 111264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; He, M.X.; Ding, Q. Vibration Suppression by Mistuning Acoustic Black Hole Dynamic Vibration Absorbers. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 542, 117370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Zuo, L. Tuned Nonlinear Spring-Inerter-Damper Vibration Absorber for Beam Vibration Reduction Based on the Exact Nonlinear Dynamics Model. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 509, 116246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Ding, H.; Wang, K. Micro-Vibration Mitigation of a Cantilever Beam by One-Third Power Nonlinear Energy Sinks. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, H. Vibration Suppressing and Energy Harvesting Research of an Elastic Beam by Utilizing an Adjustable Imperfect Nonlinear Energy Sink. Energy 2025, 322, 135663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Hong, X. Stability and Nonlinear Vibration Characteristics of Cantilevered Fluid-Conveying Pipe with Nonlinear Energy Sink. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205, 111987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Sun, W.; Luo, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X. Semi-Analytical Dynamic Modeling and Vibration Reduction Topology Optimization of the Bolted Thin Plate with Partially Attached Constrained Layer Damping. Compos. Struct. 2024, 328, 117739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Chu, C.; Wu, Q.; Chen, G.; Qi, Z.; Xie, S.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Tan, D.; Wen, B. A Nonlinear Vibration Model of Fiber Metal Laminated Thin Plate Treated with Constrained Layer Damping Patches. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2024, 106, 105278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.C.; Sun, X.G.; Wang, Y.Q. Vibration Control of Piezoelectric Beams with Active Constrained Layer Damping Treatment Using LADRC Algorithm. Structures 2024, 62, 106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couet, M.; Deü, J.F.; Rouleau, L.; Thouverez, F.; Gruin, M. Impact of Constrained Layer Damping Patches on the Dynamic Behavior of a Turbofan Bladed Disk. J. Sound Vib. 2025, 606, 119002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Du, D.; Xu, K.; Li, H. Integrated Design of Intelligent Structures for Composite Laminates with Embedded MFCs: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Study. Compos. Struct. 2025, 357, 118913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.F.; Ding, H.; Ji, J.C.; Wei, K.X.; Jing, X.J.; Chen, L.Q. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Dynamic Design of Nonlinear Energy Sinks. Eng. Struct. 2024, 313, 118228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Meng, Z. Multi-Channel Adaptive Active Vibration Control of Piezoelectric Smart Plate with Online Secondary Path Modelling Using PZT Patches. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 120, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameury, C.; Amabili, M. Active Vibration Control of a Curved Sandwich Beam Using a Nonlinear PPF Algorithm. Compos. Struct. 2025, 367, 119271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyuan, G.; Yiru, W.; Muyao, S.; Xiaojin, Z. Theoretical and Experimental Investigation Study of Discrete Time Rate-dependent Hysteresis Modeling and Adaptive Vibration Control for Smart Flexible Beam with MFC Actuators. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2022, 344, 113738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Rimašauskienė, R.; Jūrėnas, V.; Mahato, S. Experimental Investigation of Vibration Amplitude Control in Additive Manufactured PLA and PLA Composite Structures with MFC Actuator. Eng. Struct. 2023, 294, 116802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Yan, S.; Sun, H. Vibration Mitigation of a Cable-Stayed Beam with Positive Position Feedback Control in Frequency and Time Domains. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameury, C.; Ferrari, G.; Franchini, G.; Amabili, M. An Experimental Approach to Multi-Input Multi-Output Nonlinear Active Vibration Control of a Clamped Sandwich Beam. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 216, 111496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shen, L.; Shao, J.; Fang, J. Simulation and Experiment of Active Vibration Control Based on Flexible Piezoelectric MFC Composed of PZT and PI Layer. Polymers 2023, 15, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, F.; Ding, H.; Liu, T.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Iqbal, A. An Adaptive Active Vibration Control for Flexible Beam Systems under Unknown Deterministic Disturbances. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 112447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Yu, M.; Liu, C. Theoretical and Experimental Study of Active Vibration Control of Rotating Composite Laminated Beams Using Fx-NLMS Algorithm. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 111959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, P.; Liu, C. An Analytical and Experimental Study on Adaptive Active Vibration Control of Sandwich Beam. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 232, 107634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, R.; Chauhan, V.S.; Vaish, R. Fuzzy Logic Based Active Vibration Control Using Novel Photostrictive Composites. Compos. Struct. 2023, 313, 116919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Luo, H.; Shen, J.; Zhang, R. A Method of Layout Optimization for MFC Actuators in Active Vibration Control of Composite Laminates. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 220, 109961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Su, Z. Active Vibration Control of Elastically Restrained Rotating Beams with Piezoelectric Patches Placement Optimization. J. Sound Vib. 2025, 619, 119426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.C.; Hu, Z. li Biological Evolution Reinforcement Learning Vibration Control of a Three-Flexible-Beam Coupling Multi-Body System. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 231, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, X. Fuzzy Neural Network Vibration Control of Three Flexible Coupled Beams. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 305, 110766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, L.; Li, X. Key Technologies in Active Microvibration Isolation Systems: Modeling, Sensing, Actuation, and Control Algorithms. Measurement 2023, 222, 113658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bi, K.; Han, Q.; Ma, R. A State-of-the-Art Review on Negative Stiffness-Based Structural Vibration Control. Eng. Struct. 2025, 323, 119247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Jing, Y.; Cao, X.; Yuan, S.; Luo, J.; Pu, H. A Novel Permanent Magnet Vibration Isolator with Wide Stiffness Range and High Bearing Capacity. Mechatronics 2024, 98, 103119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Zhong, S.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, C.; Bai, R.; Liu, M.; et al. Design and Validation of an In-Plane Electromagnetic Negative Stiffness Mechanism. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 294, 110268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.B.; Jiang, L.J.; Chen, D.C. Dynamic Modelling and Control of a Rotating Euler–Bernoulli Beam. J. Sound Vib. 2004, 274, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.T.; Nguyen, Q.C. Dynamic Model of a Three-Dimensional Flexible Cantilever Beam Attached a Moving Hub. In Proceedings of the 2017 11th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 17–20 December 2017; pp. 2744–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, P.; Chen, G.; Li, K.; Meng, Y.; Ran, J.; Lou, Y. Active Vibration Control of the Cantilever Beam Using a Manipulator. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Real-Time Computing and Robotics (RCAR), Xining, China, 15–19 July 2021; pp. 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoun, G.; Yonnet, J.P. 3D Analytical Calculation of the Forces Exerted between Two Cuboidal Magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1984, 20, 1962–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.; Corigliano, A.; Ardito, R. Numerical and Experimental Evaluation of the Magnetic Interaction for Frequency Up-Conversion in Piezoelectric Vibration Energy Harvesters. Meccanica 2022, 57, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, L.; Han, B.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, W. Analysis and Design of a Novel Arrayed Magnetic Spring with High Negative Stiffness for Low-Frequency Vibration Isolation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 216, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Costa-Castello, R.; Na, J.; De La Torre, O.; Escaler, X. Modeling and Adaptive Parameter Estimation for a Piezoelectric Cantilever Beam. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2023, 70, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantilever beam | Length (lb) × width (wb) × thickness (hb) | 200 × 18 × 0.8 | mm3 |

| Elasticity modulus | 200 | GPa | |

| Density | 7850 | kg/m3 | |

| NSMS | Length (2a) × width (2b) × height (2c) of Adjustable magnet | 15 × 15 × 5 | mm3 |

| Length (2a′) × width (2b′) × height (2c′) of Movable magnet | 15 × 15 × 4 | mm3 | |

| Polarization J | 1.42 | T | |

| MFC | Length (la) × width (wa) × thickness (ha) | 28 × 14 × 0.3 | mm3 |

| Elastic modulus | 30.336 | GPa | |

| Piezoelectric constant d33 | 374 × 10−12 | C/N | |

| Parameters | Beam | Beam with IAF | Beam with NSMS | Beam with NSMS and IAF | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resonance frequency | 9 | 9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | Hz |

| Resonance peak | 22.7 | 7.7 | 19.4 | 3.6 | dB |

| Initial vibration isolation frequency | 15.3 | 15.3 | 4.6 | 4.6 | Hz |

| RMS of vibration amplitude | 0.03 | 0.02 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 1.77 × 10−3 | g |

| Vibration attenuation rate | −50% | 0% | 87% | 91% | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, W.; Feng, X.; Ding, J.; Sun, Y.; Pu, H.; Liao, S. Active–Passive Vibration Control of Cantilever Beam Based on Magnetic Spring with Negative Stiffness and Piezoelectric Actuator. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121307

Wang M, Jiang Z, Jiang W, Feng X, Ding J, Sun Y, Pu H, Liao S. Active–Passive Vibration Control of Cantilever Beam Based on Magnetic Spring with Negative Stiffness and Piezoelectric Actuator. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121307

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Min, Zhiwei Jiang, Wei Jiang, Xianghui Feng, Jiheng Ding, Yi Sun, Huayan Pu, and Songquan Liao. 2025. "Active–Passive Vibration Control of Cantilever Beam Based on Magnetic Spring with Negative Stiffness and Piezoelectric Actuator" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121307

APA StyleWang, M., Jiang, Z., Jiang, W., Feng, X., Ding, J., Sun, Y., Pu, H., & Liao, S. (2025). Active–Passive Vibration Control of Cantilever Beam Based on Magnetic Spring with Negative Stiffness and Piezoelectric Actuator. Micromachines, 16(12), 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121307