Carbon NanoFiber-Integrated VN@CNS Multilevel Architectures for High-Performance Zinc-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

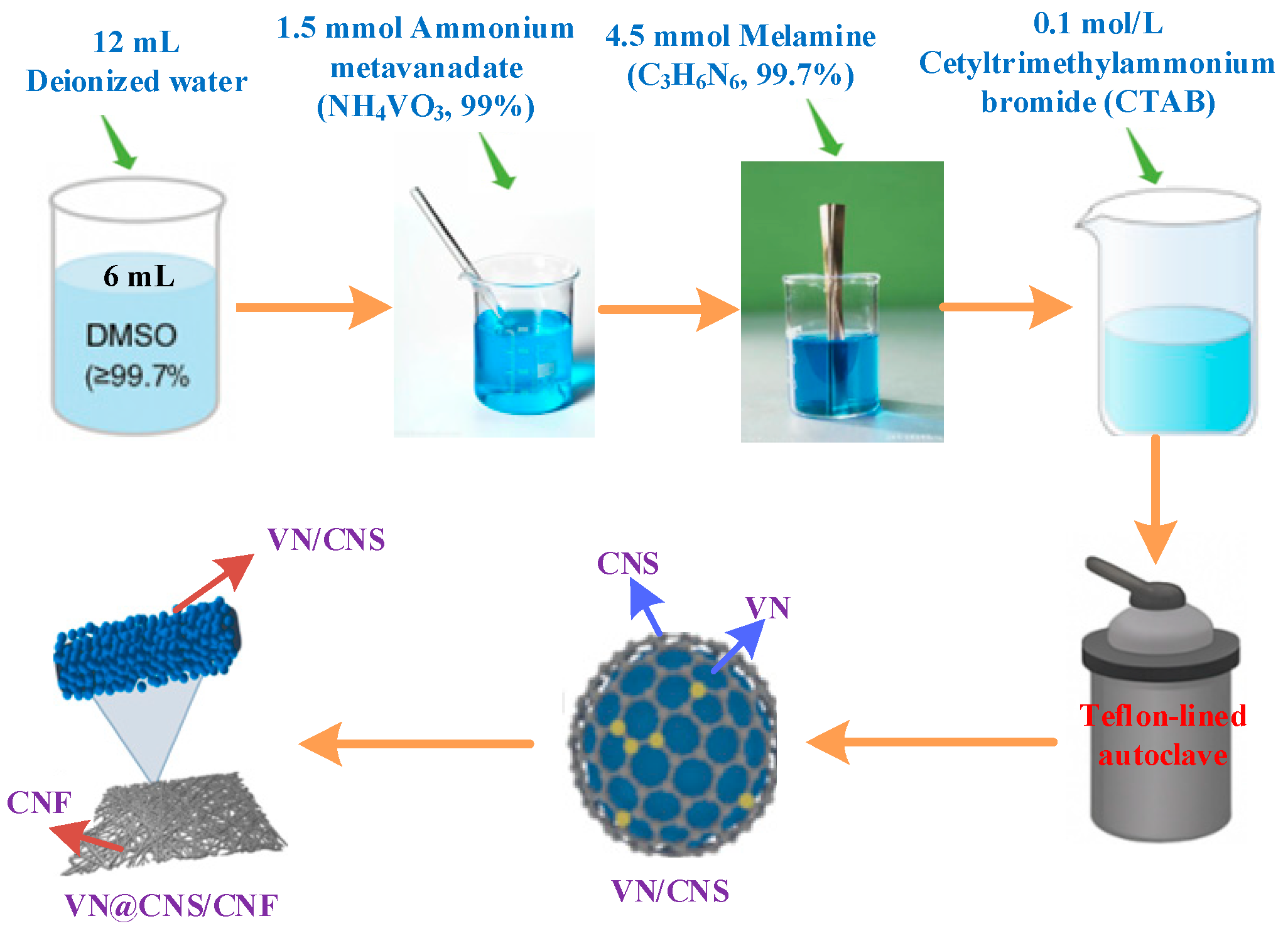

2.1. Synthesis of VN@CNS/CNF

2.2. Electrode Preparation and Cell Assembly

2.3. Experimental Instruments

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Characterization of VN@CNS/CNF

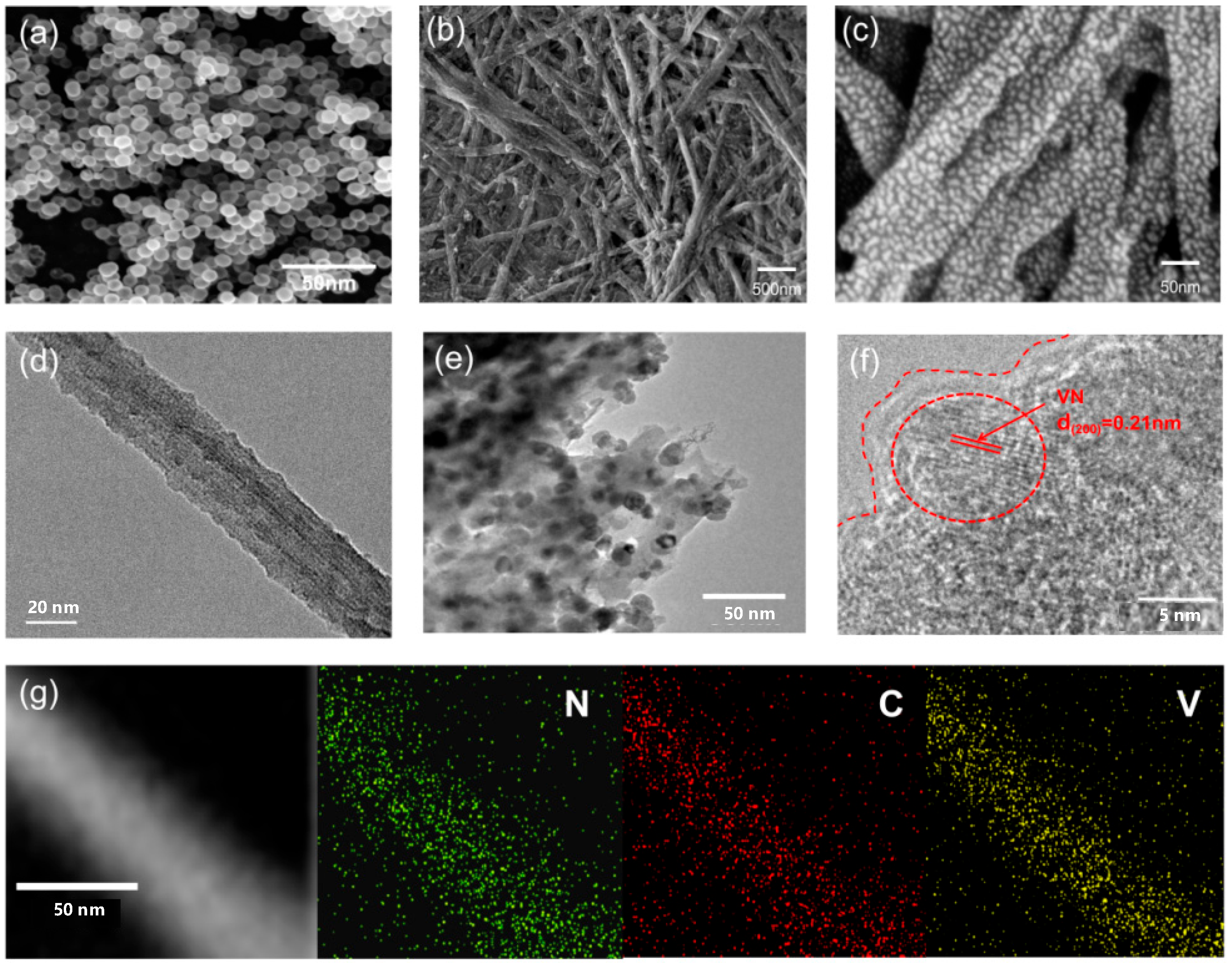

3.1.1. SEM and TEM Characterization

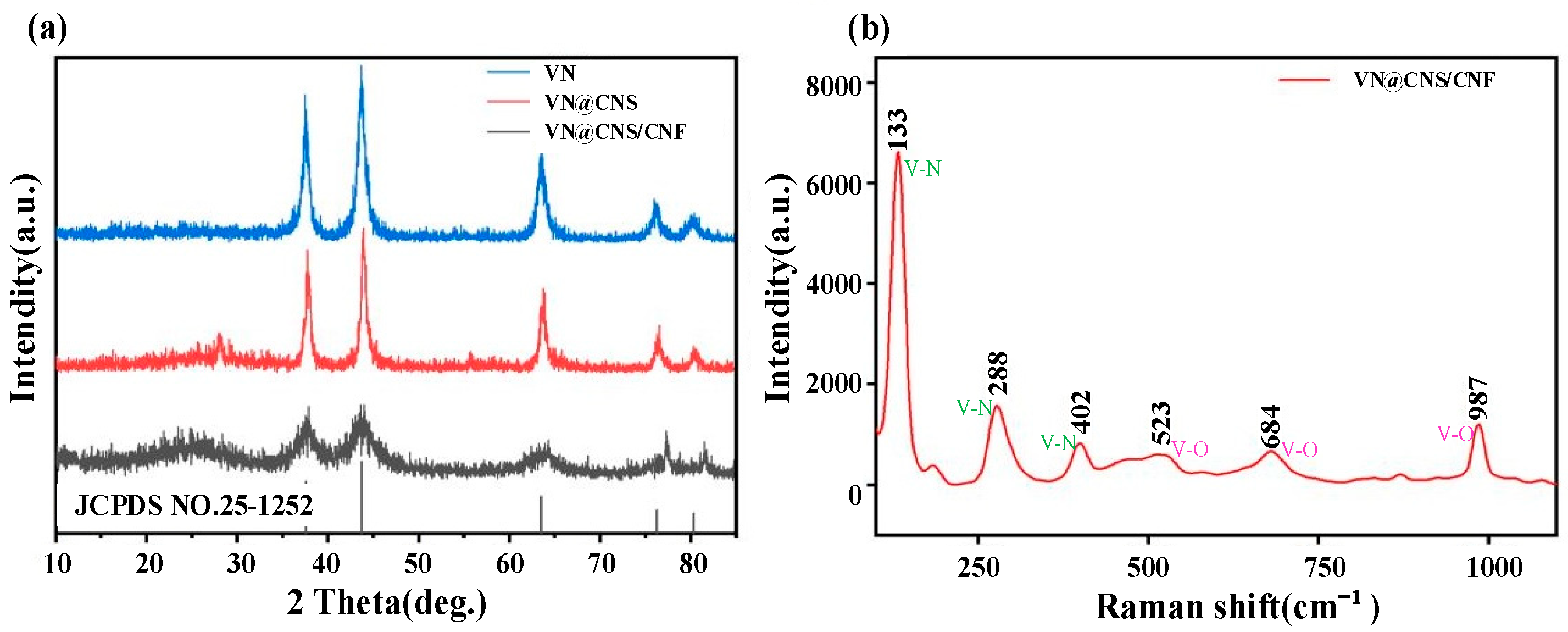

3.1.2. XRD and Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

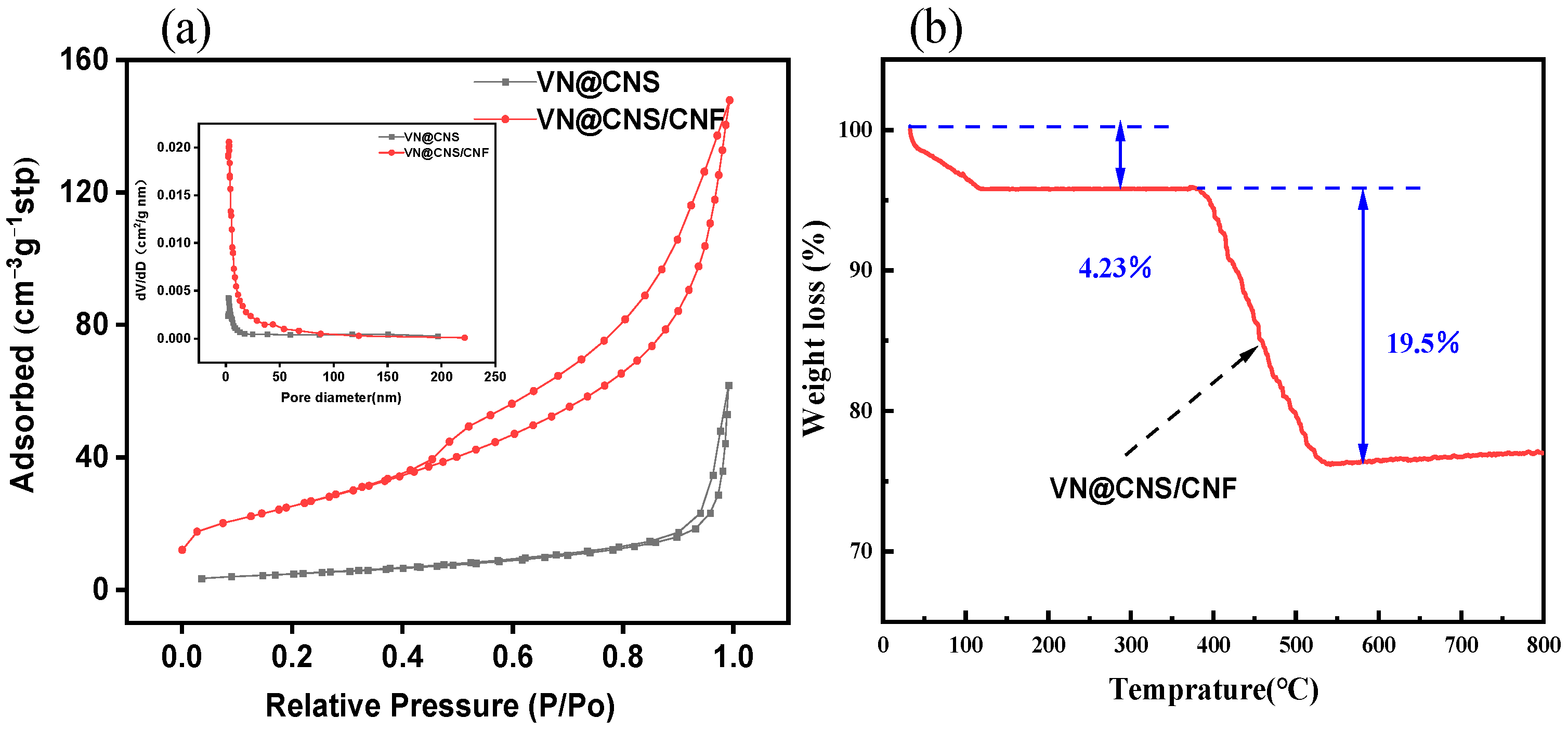

3.1.3. Nitrogen Adsorption–Desorption and Thermogravimetric Analysis

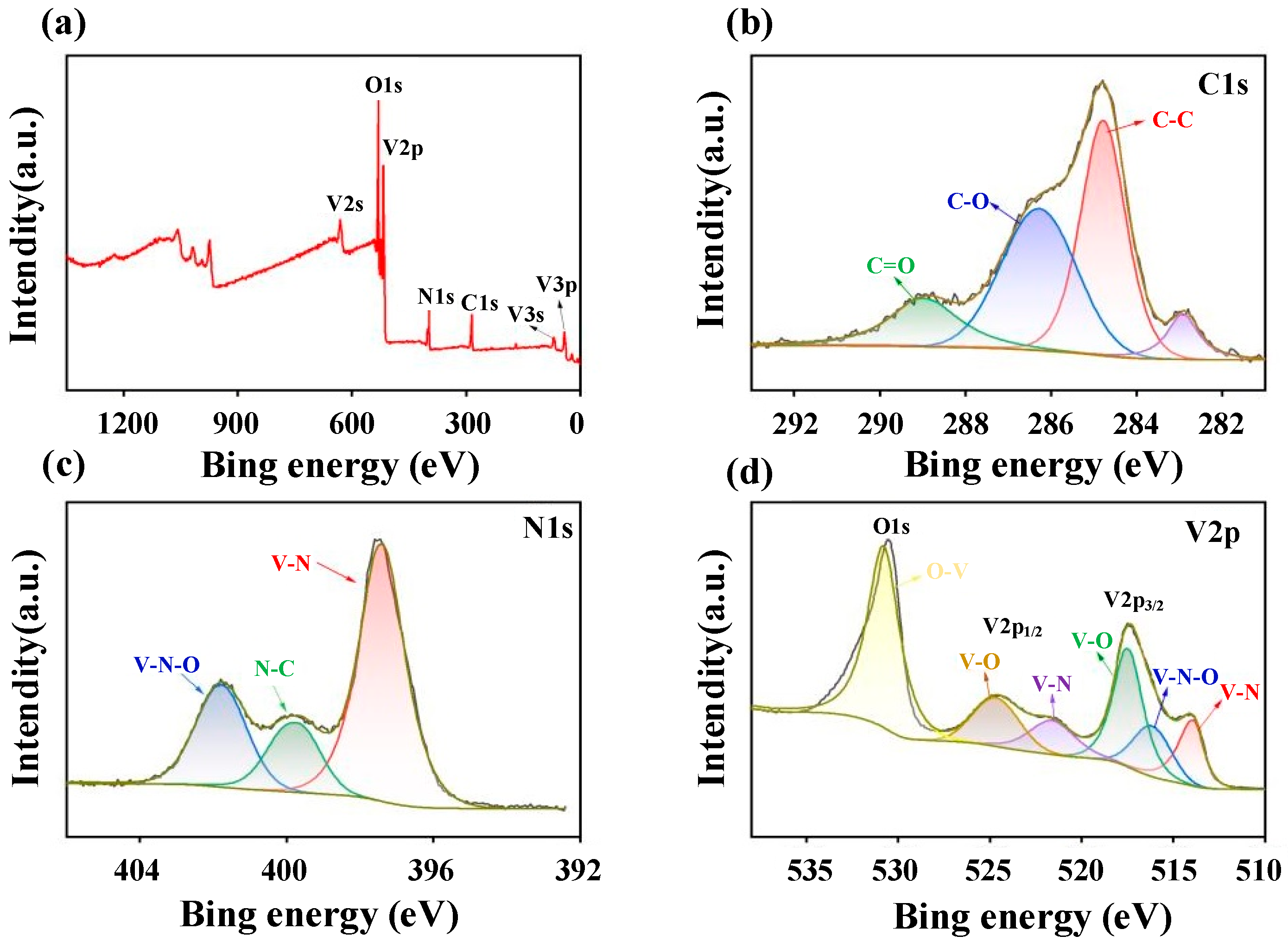

3.1.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

3.2. Electrochemical Performance of VN@CNS/CNF Electrodes

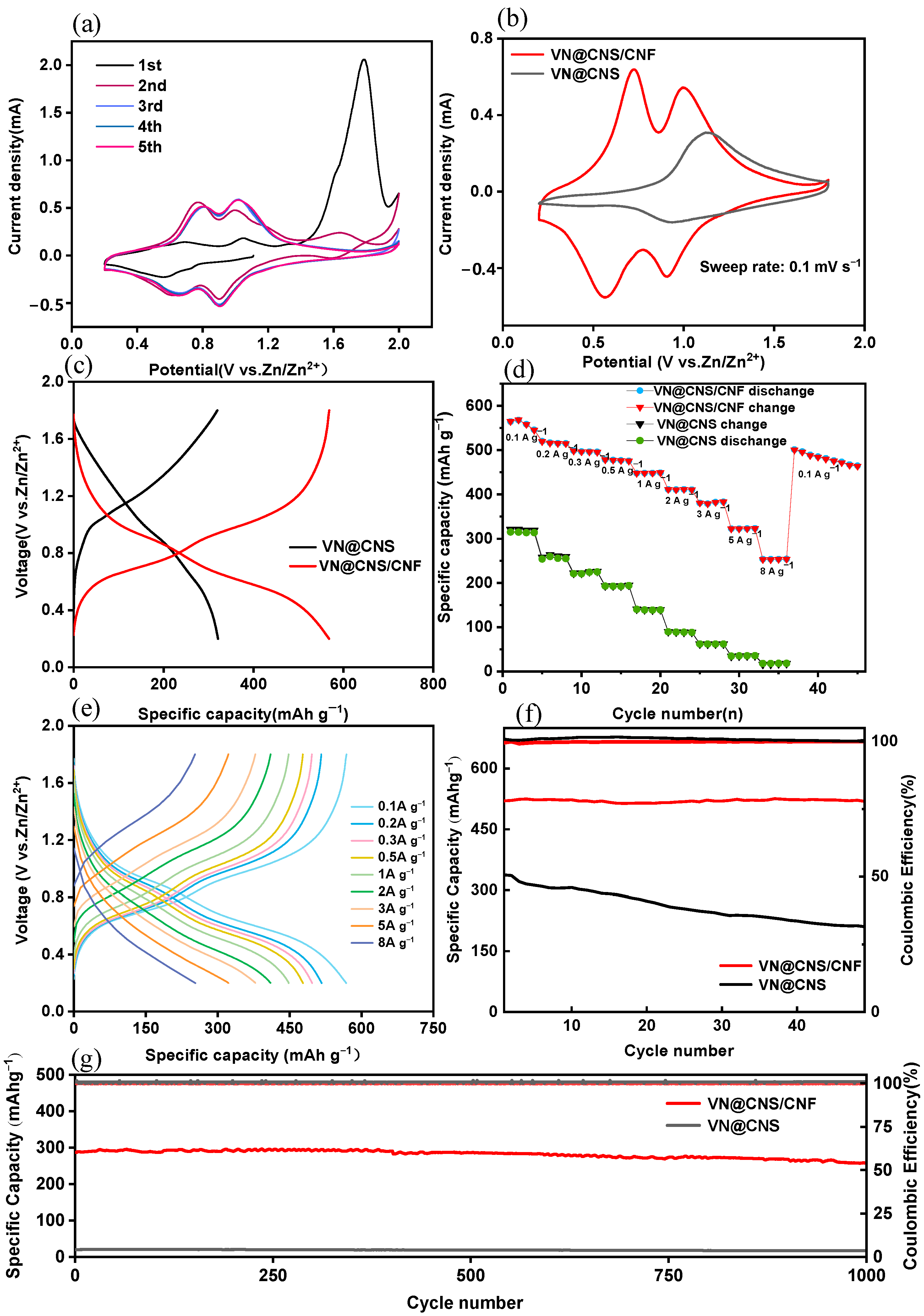

3.2.1. Cyclic Voltammetry and Galvanostatic Charge–Discharge Performance

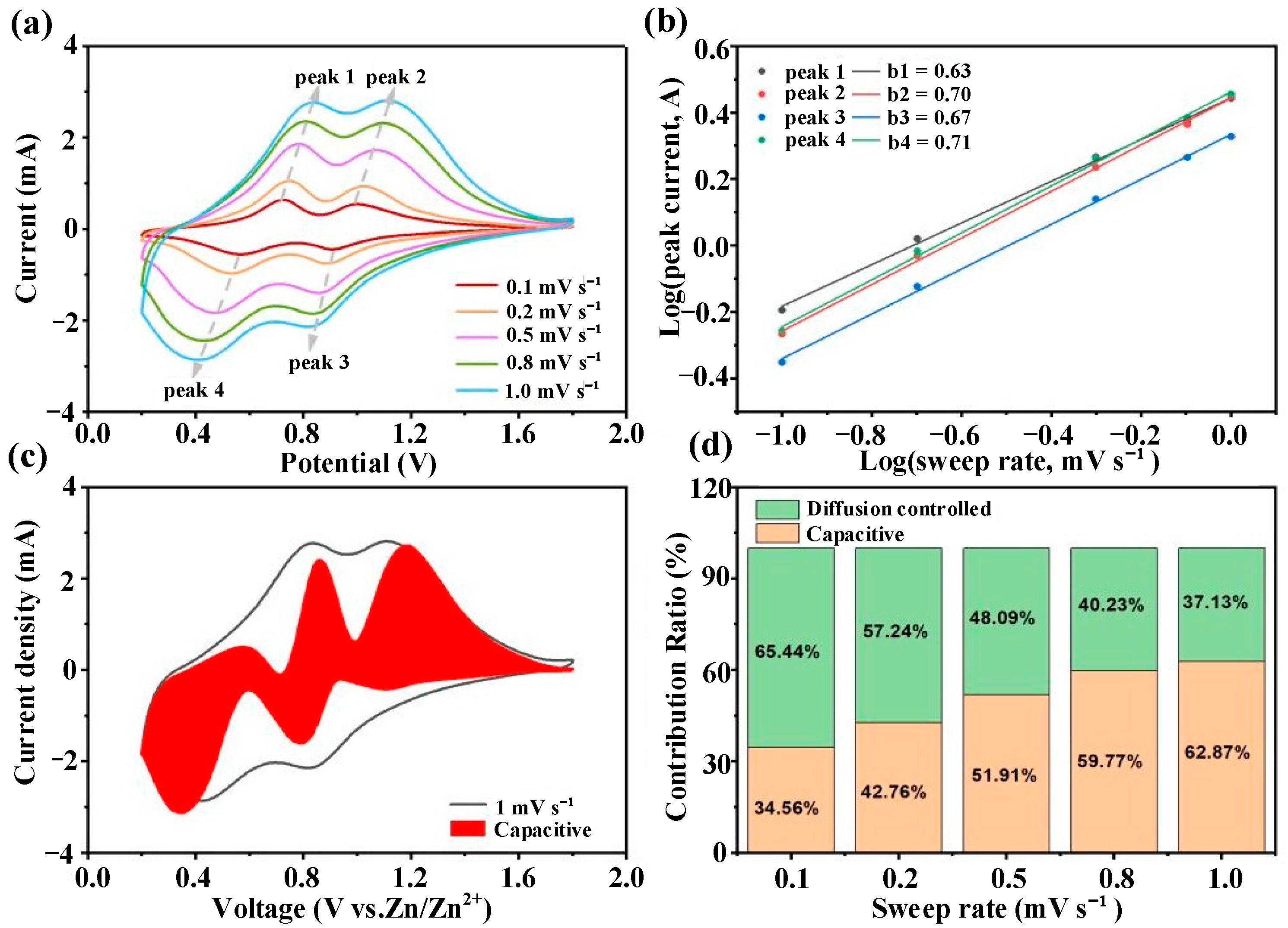

3.2.2. Electrochemical Kinetics Analysis

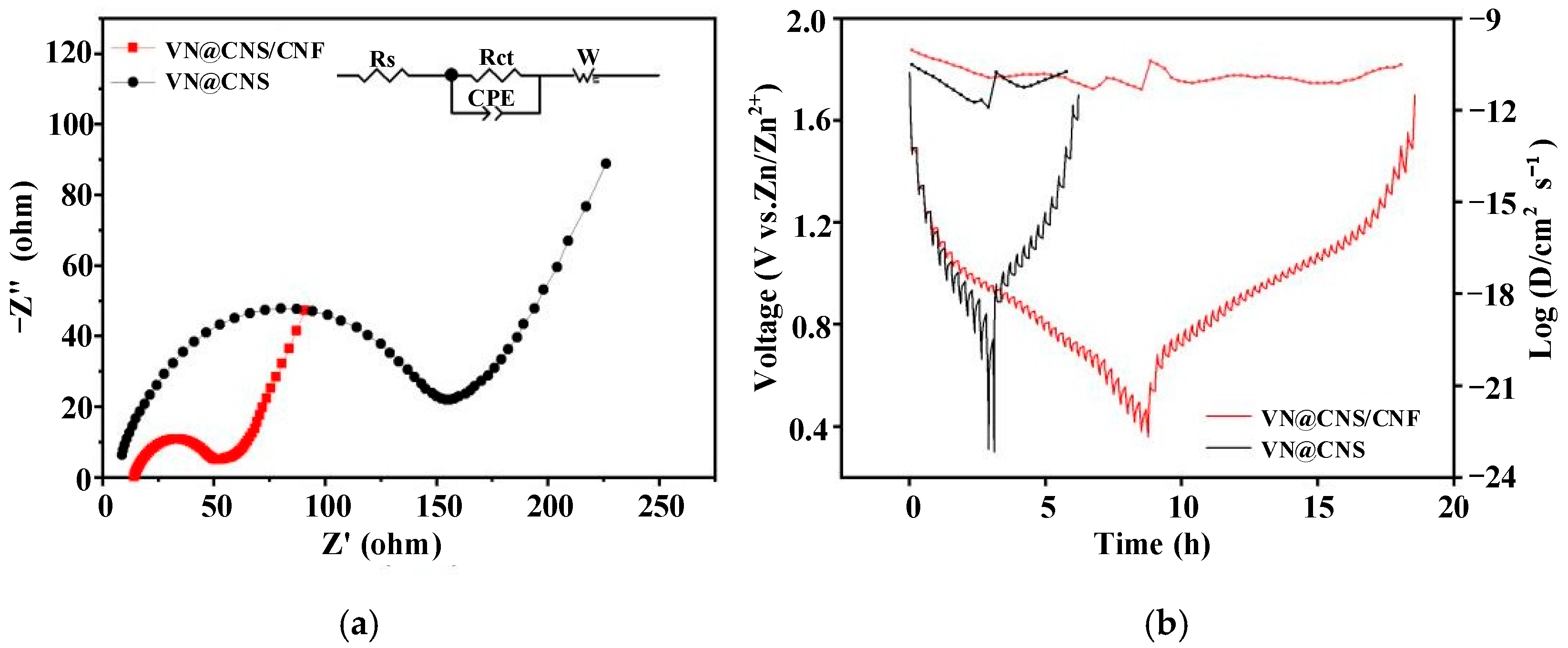

3.2.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhi, C.; Chen, S. Recent advances in electrolytes for “beyond aqueous” zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, 2106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Diao, J.; Henkelman, G.; Mullins, C. Anion-regulated electric double layer and progressive nucleation enable uniform and nanoscale Zn deposition for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Liu, C.; Neale, Z.; Yang, J.; Cao, G. Active materials for aqueous zinc ion batteries: Synthesis, crystal structure, morphology, and electrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7795–7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Yan, M.; Liao, X.; Luo, Y.; Nan, C. Reversible V3+/V5+ double redox in lithium vanadium oxide cathode for zinc storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 29, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhan, C.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Cao, X.; Dou, S.; Xiao, Y. Metal organic framework-based cathode materials for aqueous zinc-ion batteries: Recent advances and perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 65, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, J. Recent advances in cathode materials of rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 7, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, T.; Gong, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Di, J. Triggering high capacity and superior reversibility of manganese oxides cathode via magnesium modulation for Zn/MnO2 batteries. Small 2023, 19, 2301906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Yong, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, X. Discrete V2O5/NCQDs heterogeneous assemblies synergizing built-in fields and confinement for enhanced aqueous zinc ion storage. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 253903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambandam, B.; Kim, S.; Pham, D.; Mathew, V.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Soundharrajan, V.; Kim, S.; Alfaruqi, M.; Hwang, J. Hyper oxidized V6O13+x·nH2O layered cathode for aqueous rechargeable Zn battery: Effect on dual carriers transportation and parasitic reactions. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Li, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Li, R. Zn2+ induced phase transformation of K2MnFe(CN)6 boosts highly stable zinc-ion storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Yang, X.; Lin, C.; Xiong, P.; Su, A.; Fang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fan, H.; Xiao, F.; Wei, M. Progressive activation of porous vanadium nitride microspheres with intercalation-conversion reactions toward high performance over a wide temperature range for zinc-ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 640, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lu, M.; Wang, B.; Chai, R.; Li, L.; Cai, D.; Yang, H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W. Uncover the mystery of high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries constructed by oxygen-doped vanadium nitride cathode: Cationic conversion reaction works. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Luo, L.; Song, W.; Man, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, C. Nitrogen-vacancy-rich VN clusters embedded in carbon matrix for high-performance zinc ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2308668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Khanam, Z.; Li, C.; Koroma, M.; Ouyang, T.; Hu, Y.; Shen, K.; Balogun, M. Unlatching the additional zinc storage ability of vanadium nitride nanocrystallites. Small 2024, 20, 2312036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Lu, R.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Ye, C.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, J. Zn2+-mediated catalysis for fast-charging aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Wang, S.E.; Jung, D.S. Nanoconfined vanadium nitride in 3D porous reduced graphene oxide microspheres as high-capacity cathode for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wen, C.; Xu, M.; Wen, W.; Tu, J.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, Z.; Tu, Z.; Fu, Y. In-situ construction of VN-based heterostructure with high interfacial stability and porous channel effect for efficient zinc ion storage. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 224, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, M.; Liu, H.; Dou, S.; Chong, S. Advanced anode materials for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 11220–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Mo, L.; Wei, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, G.; Hu, L. Oxygen vacancies on NH4V4O10 accelerate ion and charge transfer in aqueous zinc–ion batteries. Small 2023, 20, 2306972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Niu, C.; Han, C.; Mai, L. Universal multifunctional hydrogen bond network construction strategy for enhanced aqueous Zn2+/proton hybrid batteries. Nano Energy 2022, 100, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J. Vanadium nitride@nitrogen-doped graphene as zinc ion battery cathode with high rate capability and long cycle stability. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 2955–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liang, H.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Cai, J. Facile preparation of urchin-like morphology V2O3-VN nano-heterojunction cathodes for high-performance zinc-ion water batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 654, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Xu, W.; Ma, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhi, L. Layer-by-layer stacked vanadium nitride nanocrystals/N-doped carbon hybrid nanosheets toward high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 7607–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Xu, N.; Hou, B.; Zhao, X.; Dong, M.; Sun, C.; Wang, X.; Su, Z. Bimetallic metal–organic framework-derived graphitic carbon-coated small Co/VN nanoparticles as advanced trifunctional electrocatalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 2462–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhan, R.; Xu, M.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J. Encapsulating sulfides into tridymite/carbon reactors enables stable sodium ion conversion/alloying anode with high initial coulombic efficiency over 89%. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, P.; Sun, L.; Yang, H. In situ grown hierarchical electrospun nanofiber skeletons with embedded vanadium nitride nanograins for ultra-fast and super-long cycle life aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2202826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, L.E.; Kundu, D.; Nazar, L.F. Scientific challenges for the implementation of Zn-ion batteries. Joule 2020, 4, 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, X.; Meng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Xue, N.; Chen, Y.; Xia, X.; et al. Hydrogen-bond network sieve enables selective OH−/Cl− discrimination for stable seawater splitting at 2.0 A cm−2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025; Advance Article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Fang, G.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Long, M.; Liang, S.; Cao, G.; Pan, A. In situ defect induction in close-packed lattice plane for the efficient zinc ion storage. Small 2021, 17, e2101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Liang, S.; Chen, Z.; Cui, P.; Zhou, J. Simultaneous cationic and anionic redox reactions mechanism enabling high-rate long-life aqueous zinc-ion battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wang, B.; Wu, F.; Jian, J.; Yang, K.; Jin, F.; Cong, B.; Ning, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D. Synergistic nanostructure and heterointerface design propelled ultra-efficient in-situ self-transformation of zinc-ion battery cathodes with favorable kinetics. Nano Energy 2020, 81, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kong, L.; Kang, L.; Chen, C.; Ran, F. Intercalation structure of vanadium nitride nanoparticles growing on graphene surface toward high negative active material for supercapacitor utilization. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 781, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Gong, W.; Meng, X.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L.; Abrua, H.; Geng, J. Kinetic enhancement of sulfur cathodes by N-doped porous graphitic carbon with bound VN nanocrystals. Small 2020, 16, 20049–20050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Yan, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, H. In situ electrochemical oxidation for high-energy-density aqueous batteries: Mechanisms, materials, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 2025, e07933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Du, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Gong, Y.; Yang, S. Unlocking the potential of disordered rocksalts for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1904369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Lu, M.; Li, L.; Cai, D.; Li, J.; Cao, J.; Han, W. Hierarchical core–shell structural NiMoO4@NiS2/MoS2 nanowires fabricated via an in situ sulfurization method for high performance asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 21759–21765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.; Zhu, C.; Song, M.; Liang, P.; Zhang, X.; Tiep, N.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H. A high-rate and stable quasi-solid-state zinc-ion battery with novel 2D layered zinc orthovanadate array. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1803181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zou, L.; Liu, L.; Engelhard, M.; Liu, J. Joint charge storage for high-rate aqueous zinc–manganese dioxide batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1900567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, V.; Simon, P.; Dunn, B. Pseudocapacitive oxide materials for high-rate electrochemical energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1597–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hu, Z.; Liu, X.; Tao, Z.; Chen, J. FeSe2 Microspheres as a high-performance anode material for Na-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3305–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Xu, C. Aqueous V2O5/activated carbon zinc-ion hybrid capacitors with high energy density and excellent cycling stability. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 5478–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Carbon NanoFiber-Integrated VN@CNS Multilevel Architectures for High-Performance Zinc-Ion Batteries. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111265

Cheng Y, Zhou T, Wang J, Wang Y, Li X. Carbon NanoFiber-Integrated VN@CNS Multilevel Architectures for High-Performance Zinc-Ion Batteries. Micromachines. 2025; 16(11):1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111265

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yun, Taoyun Zhou, Jianbo Wang, Yiwen Wang, and Xinyu Li. 2025. "Carbon NanoFiber-Integrated VN@CNS Multilevel Architectures for High-Performance Zinc-Ion Batteries" Micromachines 16, no. 11: 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111265

APA StyleCheng, Y., Zhou, T., Wang, J., Wang, Y., & Li, X. (2025). Carbon NanoFiber-Integrated VN@CNS Multilevel Architectures for High-Performance Zinc-Ion Batteries. Micromachines, 16(11), 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16111265