Organ-on-a-Chip Models of the Female Reproductive System: Current Progress and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

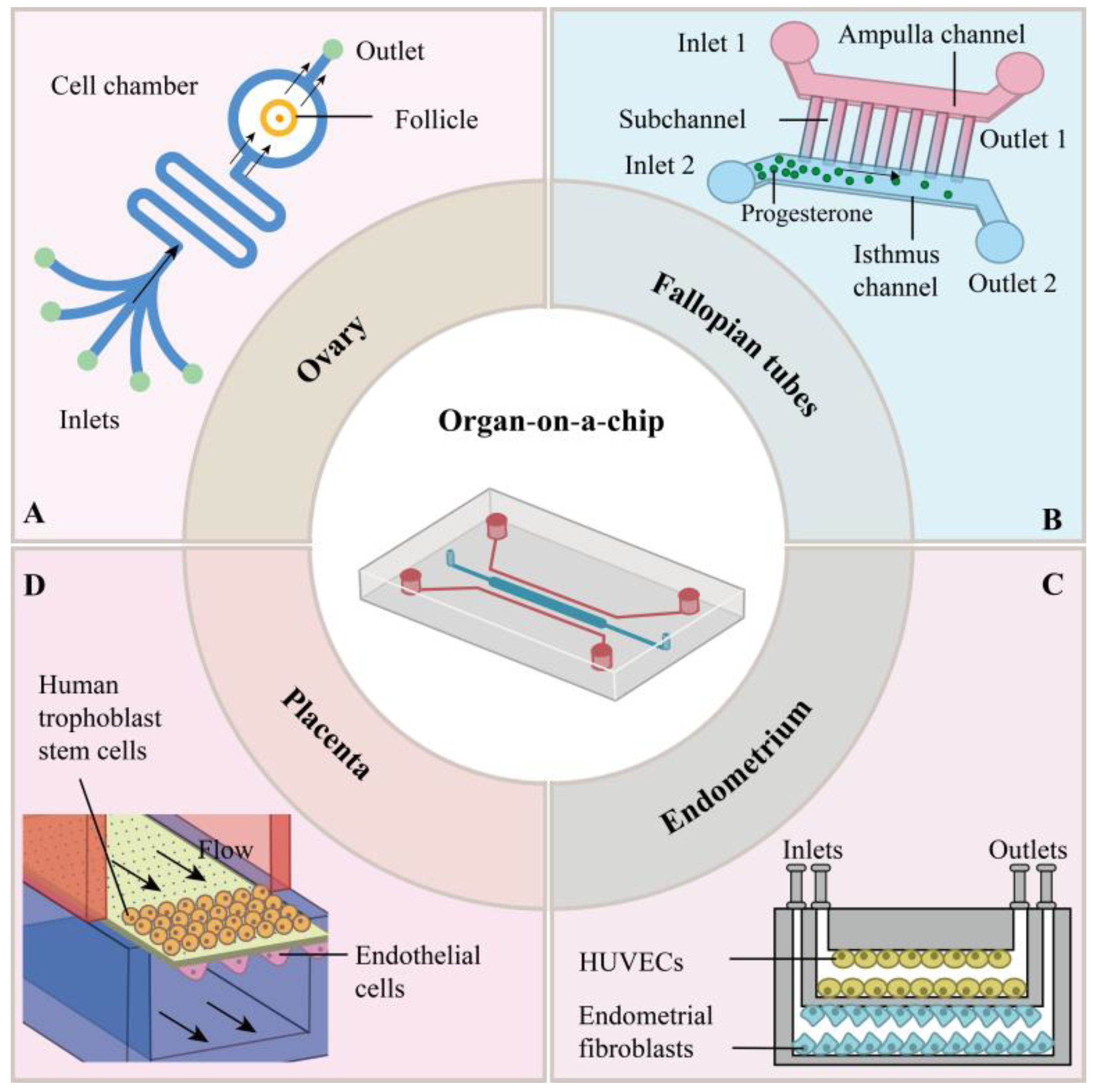

2. Organ-on-a-Chips in the Female Reproductive System

2.1. Ovarian-Organ-on-a-Chip

2.1.1. Fabrication Methods and Materials

2.1.2. Simulation of the Physiological Environment of the Ovary

2.1.3. Applications in the Study of Ovarian Diseases

| Organ/Chip Type | Construction Methods | Pros and Cons of Materials | Simulated Physiological Environment | Key Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian-organ-on-a-chip | -Microfluidic encapsulation (e.g., collagen-alginate hydrogel) -Decellularized ECM (DECM) scaffolds -Co-culture of oocytes, granulosa, and stromal cells | -PDMS Pros: gas permeability Cons: poor absorption of steroid hormones -hydrogel-based systems (e.g., gelatin, alginate, dECM) Pros: adequate diffusion properties Cons: low gas permeability | -Follicle maturation under hormone gradients -Dynamic steroidogenesis mimicking menstrual cycles | -Ovarian cancer modeling (e.g., OTME-Chip, OvCa-Chip) -Drug toxicity testing for chemotherapy agents | [24,30,31,32,36,38,39,40,41,42] |

| Fallopian-organ-on-a-chip | -Lithography/3D-printed serpentine channels -Primary epithelial cell culture with cyclic fluid shear stress | -PDMS Cons: absorbs hormones and small molecules -Sol–gel coatings: Pros: reduce absorption Cons: compromise permeability and mechanical stability; swelling and cracking | -Ciliary beating under flow conditions -Embryo transport via peristaltic motion | -Infertility mechanism studies -Enhanced embryo development and zygote genome reprogramming | [25,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] |

| Endometrial-organ-on-a-chip | -Tri-layered “epithelium-stroma-vasculature” microfluidic design -Integration of TEER/pH sensors for real-time monitoring | -PDMS Pros: hormone absorption -hydrogels Pros: gas-permeability advantages with hydrogel biomimicry -Thermoplastics Pros: excellent optics and minimal molecule absorption | -Menstrual cycle phases (proliferative/secretory) -Embryo implantation microenvironment | -Endometriosis pathogenesis (e.g., β-catenin-driven invasion) -Drug screening for endometrial receptivity | [26,51,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] |

| Placental-organ-on-a-chip | -Dual-channel system mimicking maternal–fetal circulation -Co-culture of HUVEC (vascular) and BeWo (trophoblast) cells | -PDMS Cons: absorption of drugs and hormones -Glass Pros: optical clarity and zero absorption Cons: lacks gas permeability -SLA/DLP using PEGDA-based resins Pros: low absorption and gas permeability Cons: low transparency and architectural flexibility | -Nutrient/toxin transport across placental barrier -Hypoxia-induced preeclampsia pathology | -Bacterial infection dynamics (e.g., E. coli-triggered inflammation) -Drug transfer studies (e.g., glyburide) | [27,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] |

| Multi-organ-chip | -EVATAR platform (integration of ovary, uterus, cervix, liver) -Modular microfluidic interconnections | - | -Hormonal crosstalk (e.g., 28-day menstrual cycle) -Systemic drug metabolism and toxicity analysis | -PCOS studies -Chemotherapy toxicity assessment (e.g., paclitaxel) | [42,77,78] |

2.2. Fallopian-Organ-on-a-Chip

2.2.1. Fabrication Methods and Materials

2.2.2. Simulation of the Physiological Environment of Fallopian Tubes

2.2.3. Applications in the Study of Fallopian Tube Diseases

2.3. Endometrial-Organ-on-a-Chip

2.3.1. Fabrication Methods and Materials

2.3.2. Simulation of the Physiological Environment of Endometrium

2.3.3. Applications in the Study of Endometrium Diseases

2.4. Placental-Organ-on-a-Chip

2.4.1. Fabrication Methods and Materials

2.4.2. Simulation of the Physiological Environment of Placenta

2.4.3. Applications in the Study of Placental Diseases

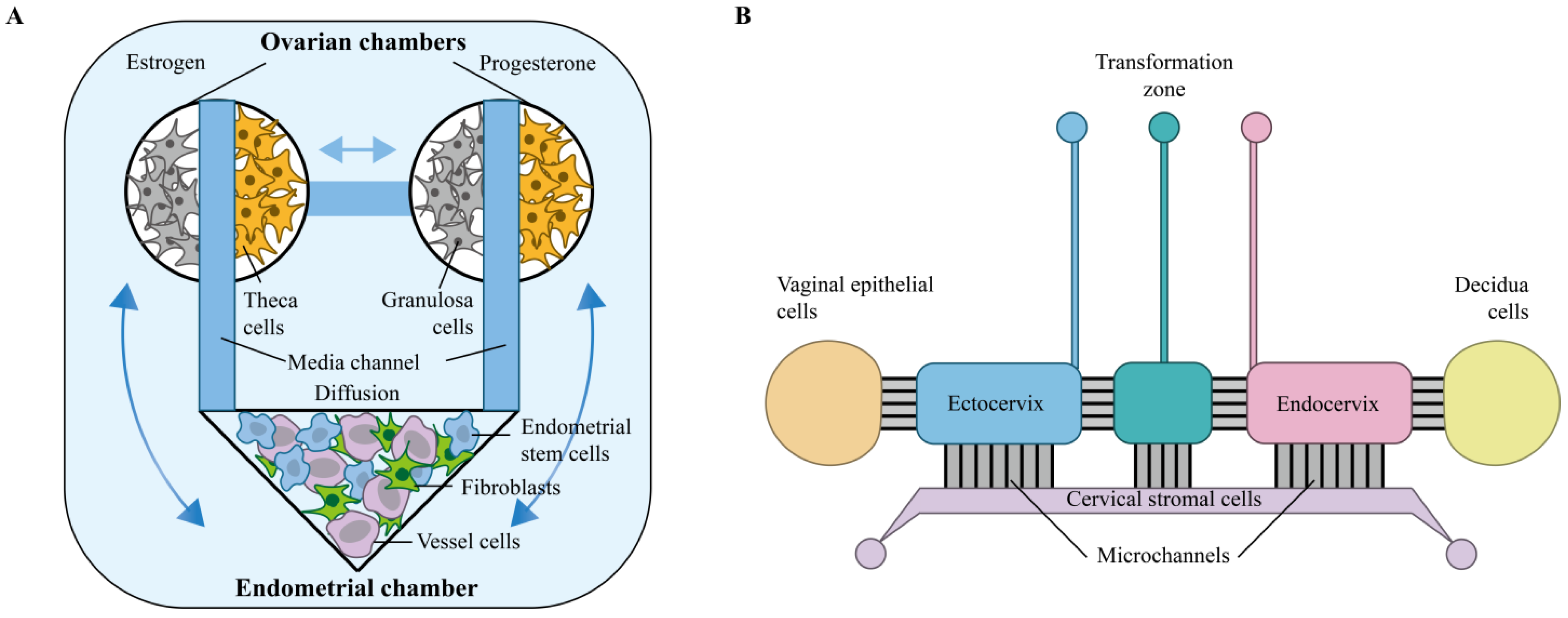

3. Joint Multi-Organ-on-a-Chip Study of the Female Reproductive System

3.1. Multi-Organ-Chip

3.2. EVATAR

4. Integrated Readouts for Functional Assessment of Female Reproductive OOC Models

5. Applications of OOCs for Female Reproductive System Organs

5.1. Drug Discovery and Screening

5.2. Modeling of Female Diseases

5.3. Promotion of Research in Assisted Reproductive Medicine

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

6.1. Challenges and Limitations

6.2. Directions for Improvement and Innovation

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, S.; Lopez-Tello, J.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N. Developmental programming of the female reproductive system—A review. Biol. Reprod. 2020, 104, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pask, A. The Reproductive System. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 886, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, R.B.; Wentzensen, N.; Guido, R.S.; Schiffman, M. Cervical Cancer Screening: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretsadik, A.; Bogale, N.; Dulla, D. Descriptive epidemiology of gynaecological cancers in southern Ethiopia: Retrospective cross-sectional review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes Soares, C.; Midlej, V.; de Oliveira, M.E.; Benchimol, M.; Costa, M.L.; Mermelstein, C. 2D and 3D-organized cardiac cells shows differences in cellular morphology, adhesion junctions, presence of myofibrils and protein expression. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38147. [Google Scholar]

- Francés-Herrero, E.; Lopez, R.; Hellström, M.; de Miguel-Gómez, L.; Herraiz, S.; Brännström, M.; Pellicer, A.; Cervelló, I. Bioengineering trends in female reproduction: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 798–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Mokshagundam, S.; Herington, J.L.; Ding, T.; Osteen, K.G. Rodent Models of Experimental Endometriosis: Identifying Mechanisms of Disease and Therapeutic Targets. Curr. Womens Health Rev. 2018, 14, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.A.; Pearson, A.M.; Slack, J.L.; Por, E.D.; Scribner, A.N.; Eti, N.A.; Burney, R.O. Endometriosis in the Mouse: Challenges and Progress Toward a ‘Best Fit’ Murine Model. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 806574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, F.; Wibisono, H.; Mon Khine, Y.; Harada, T. Animal models for research on endometriosis. Front. Biosci. 2021, 13, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Aoki, H.; Tamura, K.; Takeda, A.; Minato, S.; Masaki, R.; Yanagihara, R.; Hayashi, N.; Yano, Y.; et al. A novel PCOS rat model and an evaluation of its reproductive, metabolic, and behavioral phenotypes. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2022, 21, e12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varughese, E.E.; Adams, G.P.; Leonardi Carlos, E.P.; Malhi, P.S.; Paul, B.; Mary, K.; Jaswant, S. Development of a domestic animal model for endometriosis: Surgical induction in the dog, pigs, and sheep. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2018, 10, 228402651877394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamzadeh, V.; Sohrabi-Kashani, A.; Shen, M.; Juncker, D. Digital Manufacturing of Functional Ready-to-Use Microfluidic Systems. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2303867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, N.; Urrios, A.; Kang, S.; Folch, A. The upcoming 3D-printing revolution in microfluidics. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 1720–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.T.; Ahmadianyazdi, A.; Folch, A. A ‘print-pause-print’ protocol for 3D printing microfluidics using multimaterial stereolithography. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 1243–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.C.; Tu, Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, J. Construction of oxygen and chemical concentration gradients in a single microfluidic device for studying tumor cell-drug interactions in a dynamic hypoxia microenvironment. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galie, P.A.; Nguyen, D.H.; Choi, C.K.; Cohen, D.M.; Janmey, P.A.; Chen, C.S. Fluid shear stress threshold regulates angiogenic sprouting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7968–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.T.; Lin, R.Z.; Chen, R.J.; Chin, C.K.; Gong, S.E.; Chang, H.Y.; Peng, H.L.; Hsu, L.; Yew, T.R.; Chang, S.F.; et al. Liver-cell patterning lab chip: Mimicking the morphology of liver lobule tissue. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 3578–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.; Kim, H. Characterization of a microfluidic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (μBBB). Lab Chip 2012, 12, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Leslie, D.C.; Matthews, B.D.; Fraser, J.P.; Jurek, S.; Hamilton, G.A.; Thorneloe, K.S.; McAlexander, M.A.; Ingber, D.E. A human disease model of drug toxicity-induced pulmonary edema in a lung-on-a-chip microdevice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 159ra147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santbergen, M.J.C.; van der Zande, M.; Gerssen, A.; Bouwmeester, H.; Nielen, M.W.F. Dynamic in vitro intestinal barrier model coupled to chip-based liquid chromatography mass spectrometry for oral bioavailability studies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.; Kuramoto, G.; Homma, J.; Sakaguchi, K.; Shimizu, T. In-Vitro Decidualization with Different Progesterone Concentration: Development of a Hormone-Responsive 3D Endometrial Tissue Using Rat Endometrial Tissues. Cureus 2023, 15, e49613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingber, D.E. Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling, drug development and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Fu, J. Integrated micro/nanoengineered functional biomaterials for cell mechanics and mechanobiology: A materials perspective. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1494–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.U.R.; Fu, M.; Deng, J.; Geng, C.; Luo, Y.; Lin, B.; Yu, X.; Liu, B. A Microfluidic Device for Culturing an Encapsulated Ovarian Follicle. Micromachines 2017, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.X.; Wu, Y.; Luo, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, W.; Tang, J.; Shi, H.; Gao, H.; et al. Escaping Behavior of Sperms on the Biomimetic Oviductal Surface. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnecco, J.S.; Pensabene, V.; Li, D.J.; Ding, T.; Hui, E.E.; Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Osteen, K.G. Compartmentalized Culture of Perivascular Stroma and Endothelial Cells in a Microfluidic Model of the Human Endometrium. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 1758–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Rong, L.; Qin, J. Self-assembled human placental model from trophoblast stem cells in a dynamic organ-on-a-chip system. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Orisaka, M.; Wang, H.; Orisaka, S.; Thompson, W.; Zhu, C.; Kotsuji, F.; Tsang, B.K. Gonadotropin and intra-ovarian signals regulating follicle development and atresia: The delicate balance between life and death. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 3628–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.C.; Blanchard, Z.; Maurer, K.A.; Gertz, J. Estrogen Signaling in Endometrial Cancer: A Key Oncogenic Pathway with Several Open Questions. Horm. Cancer 2019, 10, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashzadeh, A.; Moghassemi, S.; Shavandi, A.; Amorim, C.A. A review on biomaterials for ovarian tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2021, 135, 8–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, W.Y.; Chua, C.K.; Leong, K.F.; Chandrasekaran, M. Rapid prototyping in tissue engineering: Challenges and potential. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yu, Y.; Hu, Y.; He, X.; Berk Usta, O.; Yarmush, M.L. Generation and manipulation of hydrogel microcapsules by droplet-based microfluidics for mammalian cell culture. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1913–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, L.D.; Jain, A. The prospects of microphysiological systems in modeling platelet pathophysiology in cancer. Platelets 2023, 34, 2247489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Mathur, T.; Handley, K.F.; Hu, W.; Afshar-Kharghan, V.; Sood, A.K.; Jain, A. OvCa-Chip microsystem recreates vascular endothelium-mediated platelet extravasation in ovarian cancer. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 3329–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laronda, M.M.; Rutz, A.L.; Xiao, S.; Whelan, K.A.; Duncan, F.E.; Roth, E.W.; Woodruff, T.K.; Shah, R.N. A bioprosthetic ovary created using 3D printed microporous scaffolds restores ovarian function in sterilized mice. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.K.; Agarwal, P.; Huang, H.; Zhao, S.; He, X. The crucial role of mechanical heterogeneity in regulating follicle development and ovulation with engineered ovarian microtissue. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5122–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghannam, F.; Alayed, M.; Alfihed, S.; Sakr, M.A.; Almutairi, D.; Alshamrani, N.; Al Fayez, N. Recent Progress in PDMS-Based Microfluidics Toward Integrated Organ-on-a-Chip Biosensors and Personalized Medicine. Biosensors 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meer, B.J.; de Vries, H.; Firth, K.S.A.; van Weerd, J.; Tertoolen, L.G.J.; Karperien, H.B.J.; Jonkheijm, P.; Denning, C.; IJzerman, A.P.; Mummery, C.L. Small molecule absorption by PDMS in the context of drug response bioassays. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavati, B.; Oleinikov, A.V.; Du, E. Development of an Organ-on-a-Chip-Device for Study of Placental Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pors, S.E.; Ramløse, M.; Nikiforov, D.; Lundsgaard, K.; Cheng, J.; Andersen, C.Y.; Kristensen, S.G. Initial steps in reconstruction of the human ovary: Survival of pre-antral stage follicles in a decellularized human ovarian scaffold. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Monteiro Melo Ferraz, M.; Nagashima, J.B.; Venzac, B.; Le Gac, S.; Songsasen, N. A dog oviduct-on-a-chip model of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Coppeta, J.R.; Rogers, H.B.; Isenberg, B.C.; Zhu, J.; Olalekan, S.A.; McKinnon, K.E.; Dokic, D.; Rashedi, A.S.; Haisenleder, D.J.; et al. A microfluidic culture model of the human reproductive tract and 28-day menstrual cycle. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Karim, M.; Hasan, M.M.; Hooper, J.; Wahab, R.; Roy, S.; Al-Hilal, T.A. Cancer-on-a-Chip: Models for Studying Metastasis. Cancers 2022, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Rayamajhi, S.; Sipes, J.; Russo, A.; Pathak, H.B.; Li, K.; Sardiu, M.E.; Bantis, L.E.; Mitra, A.; Puri, R.V.; et al. Proteomic Profiling of Fallopian Tube-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Using a Microfluidic Tissue-on-Chip System. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubizarreta, M.E.; Xiao, S. Bioengineering models of female reproduction. Biodes. Manuf. 2020, 3, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, J.H.; Yu, J.; Luo, D.; Shuler, M.L.; March, J.C. Microscale 3-D hydrogel scaffold for biomimetic gastrointestinal (GI) tract model. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, M.; Rho, H.S.; Hemerich, D.; Henning, H.H.W.; van Tol, H.T.A.; Hölker, M.; Besenfelder, U.; Mokry, M.; Vos, P.; Stout, T.A.E.; et al. An oviduct-on-a-chip provides an enhanced in vitro environment for zygote genome reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Bernal, M.A.; Fazleabas, A.T. Physiologic Events of Embryo Implantation Decidualization in Human Non-Human Primates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkowski, W.; Gall-Mas, L.; Falco, M.M.; Li, Y.; Lavikka, K.; Kriegbaum, M.C.; Oikkonen, J.; Bulanova, D.; Pietras, E.J.; Voßgröne, K.; et al. A platform for efficient establishment and drug-response profiling of high-grade serous ovarian cancer organoids. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 1106–1121.e1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrecht, S.; Busschaert, P.; Qian, J.; Vanderstichele, A.; Loverix, L.; Van Gorp, T.; Van Nieuwenhuysen, E.; Han, S.; Van den Broeck, A.; Coosemans, A.; et al. High-grade serous tubo-ovarian cancer refined with single-cell RNA sequencing: Specific cell subtypes influence survival and determine molecular subtype classification. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Xavier, M.; Calero, V.; Pastrana, L.; Gonalves, C. Critical Analysis of the Absorption/Adsorption of Small Molecules by Polydimethylsiloxane in Microfluidic Analytical Devices. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoe, H.; Osaki, T.; Kawano, R.; Takeuchi], S. Parylene-coating in PDMS microfluidic channels prevents the absorption of fluorescent dyes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 150, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Toepke, M.W.; Beebe, D.J. PDMS absorption of small molecules and consequences in microfluidic applications. Lab Chip 2006, 6, 1484–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Mani, S.; Clair, G.; Olson, H.M.; Paurus, V.L.; Ansong, C.K.; Blundell, C.; Young, R.; Kanter, J.; Gordon, S.; et al. A microphysiological model of human trophoblast invasion during implantation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Yoon, M.J.; Hong, S.H.; Cha, H.; Lee, D.; Koo, H.S.; Ko, J.E.; Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Jeon, N.L.; et al. Three-dimensional microengineered vascularised endometrium-on-a-chip. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 2720–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbpour Marzouni, E.; Stern, C.; Henrik Sinclair, A.; Tucker, E.J. Stem Cells and Organs-on-chips: New Promising Technologies for Human Infertility Treatment. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 878–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.W.; Chang, P.Y.; Huang, H.Y.; Li, C.J.; Tien, C.H.; Yao, D.J.; Fan, S.K.; Hsu, W.Y.; Liu, C.H. Womb-on-a-chip biomimetic system for improved embryo culture and development. Sens. Actuat B Chem. 2016, 226, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Hu, B.; Han, Z.Q.; Zhu, J.H.; Fan, X.; Chen, X.X.; Li, Z.P.; Zhou, H. BAG2-Mediated Inhibition of CHIP Expression and Overexpression of MDM2 Contribute to the Initiation of Endometriosis by Modulating Estrogen Receptor Status. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 554190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnecco, J.S.; Brown, A.; Buttrey, K.; Ives, C.; Goods, B.A.; Baugh, L.; Hernandez-Gordillo, V.; Loring, M.; Isaacson, K.B.; Griffith, L.G. Organoid co-culture model of the human endometrium in a fully synthetic extracellular matrix enables the study of epithelial-stromal crosstalk. Med 2023, 4, 554–579.e559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksana, M. Molecular Aspects of Cancer Research Endometrium—The Prospect of Personalized Treatment. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Monteiro Melo Ferraz, M.; Nagashima, J.B.; Venzac, B.; Le Gac, S.; Songsasen, N. 3D printed mold leachates in PDMS microfluidic devices. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amend, N.; Koller, M.; Schmitt, C.; Worek, F.; Wille, T. The suitability of a polydimethylsiloxane-based (PDMS) microfluidic two compartment system for the toxicokinetic analysis of organophosphorus compounds. Toxicol. Lett. 2023, 388, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Hromada, L.; Liu, J.; Kumar, P.; DeVoe, D.L. Low temperature bonding of PMMA and COC microfluidic substrates using UV/ozone surface treatment. Lab Chip 2007, 7, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, S.K.; Whitesides, G.M. Microfluidic devices fabricated in poly(dimethylsiloxane) for biological studies. Electrophoresis 2003, 24, 3563–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, C.; Tess, E.R.; Schanzer, A.S.; Coutifaris, C.; Su, E.J.; Parry, S.; Huh, D. A microphysiological model of the human placental barrier. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3065–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, C.; Yi, Y.S.; Ma, L.; Tess, E.R.; Farrell, M.J.; Georgescu, A.; Aleksunes, L.M.; Huh, D. Placental Drug Transport-on-a-Chip: A Microengineered In Vitro Model of Transporter-Mediated Drug Efflux in the Human Placental Barrier. Adv. Health. Mater. 2018, 7, 1700786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermant, A.; Rabussier, G.; Lanz, H.L.; Davidson, L.; Porter, I.M.; Murdoch, C.E. Development of a human iPSC-derived placental barrier-on-chip model. iScience 2023, 26, 107240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, E.A.; Thadhani, R.; Benzing, T.; Karumanchi, S.A. Pre-eclampsia: Pathogenesis, novel diagnostics and therapies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.M.; Banayan, J.M.; Hofer, J.E. Pre-eclampsia through the eyes of the obstetrician anesthesiologist. Int. J. Obs. Anesth. 2019, 40, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabussier, G.; Bünter, I.; Bouwhuis, J.; Soragni, C.; van Zijp, T.; Ng, C.P.; Domansky, K.; de Windt, L.J.; Vulto, P.; Murdoch, C.E.; et al. Healthy and diseased placental barrier on-a-chip models suitable for standardized studies. Acta Biomater. 2023, 164, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yin, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Yuan, J.; Qin, J. Placental Barrier-on-a-Chip: Modeling Placental Inflammatory Responses to Bacterial Infection. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 3356–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.; Velji, Z.; Hanly, C.; Metcalfe, A. Risk of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, L.; Jeong, S.; Kim, S.; Han, A.; Menon, R. Amnion membrane organ-on-chip: An innovative approach to study cellular interactions. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8945–8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Qin, J. Microengineered hiPSC-Derived 3D Amnion Tissue Model to Probe Amniotic Inflammatory Responses under Bacterial Exposure. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 4644–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Chen, X.; Kang, Q.; Yan, X. Biomedical Application of Functional Materials in Organ-on-a-Chip. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaroud, N.B.; Dekker, R.; Serdijn, W.; Giagka, V. PDMS-Parylene Adhesion Improvement via Ceramic Interlayers to Strengthen the Encapsulation of Active Neural Implants. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 3399–3402. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.R.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, J.W.; Park, C.H.; Yu, W.J.; Lee, S.J.; Chon, S.J.; Lee, D.H.; Hong, I.S. Development of a novel dual reproductive organ on a chip: Recapitulating bidirectional endocrine crosstalk between the uterine endometrium and the ovary. Biofabrication 2020, 13, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, A.; Jorgenson, A.; Junaid, A.; Ingber, D.E. Modeling Healthy and Dysbiotic Vaginal Microenvironments in a Human Vagina-on-a-Chip. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 204, 66486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Watrelot, A. Fallopian tube subtle pathology. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, K.; Dolitsky, S.; Ludwin, I.; Ludwin, A. Modern assessment of the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes in the era of high-efficacy assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.; Green, A.; Medina, J.E.; Iyer, S.; Ohman, A.W.; McCarthy, E.T.; Reinhardt, F.; Gerton, T.; Demehin, D.; Mishra, R.; et al. Inaugurating High-Throughput Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles for Earlier Ovarian Cancer Detection. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2301930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisert, R.D.; Zavy, M.T.; Moffatt, R.J.; Blair, R.M.; Yellin, T. Embryonic steroids the establishment of pregnancy in pigs. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 1990, 40, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masuda, H.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Hiratsu, E.; Ono, M.; Nagashima, T.; Kajitani, T.; Arase, T.; Oda, H.; Uchida, H.; Asada, H.; et al. Stem cell-like properties of the endometrial side population: Implication in endometrial regeneration. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, P.A.; Critchley, H.O.; Williams, A.R.; Arends, M.J.; Saunders, P.T. New concepts for an old problem: The diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, C.; Liao, Z.; Bai, J.; Hu, D.; Yue, J.; Yang, S. Current knowledge on the role of extracellular vesicles in endometrial receptivity. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melford, S.E.; Taylor, A.H.; Konje, J.C. Of mice and (wo)men: Factors influencing successful implantation including endocannabinoids. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandt, D.; Gruber, P.; Markovic, M.; Tromayer, M.; Rothbauer, M.; Kratz, S.R.A.; Ali, S.F.; Hoorick, J.V.; Holnthoner, W.; Mühleder, S.; et al. Fabrication of biomimetic placental barrier structures within a microfluidic device utilizing two-photon polymerization. Int. J. Bioprint. 2018, 4, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hwang, H.H.; Tekkatte, C.; Lindsay, S.A.; Castro-Martinez, A.; Yu, C.; Saldana, I.; Ma, X.; Farah, O.; Parast, M.M.; et al. 3D-bioprinted placenta-on-a-chip platform for modeling the human maternal–fetal barrier. Int. J. Bioprint. 2025, 025270262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mini Placentas 3D-Printed in a Lab in Amazing World First. Available online: https://www.sciencealert.com/mini-placentas-3d-printed-in-a-lab-in-amazing-world-first (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, S. Recent development of organoids organ-on-a-chip in creation of an in vitro model of the placenta Chin. J. Reprod. Contracept. 2023, 43, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Tantengco, O.A.G.; Richardson, L.S.; Radnaa, E.; Kammala, A.K.; Kim, S.; Medina, P.M.B.; Han, A.; Menon, R. Modeling ascending Ureaplasma parvum infection through the female reproductive tract using vagina-cervix-decidua-organ-on-a-chip feto-maternal interface-organ-on-a-chip. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.A.; Hartse, B.X.; Niaraki Asli, A.E.; Taghavimehr, M.; Hashemi, N.; Abbasi Shirsavar, M.; Montazami, R.; Alimoradi, N.; Nasirian, V.; Ouedraogo, L.J.; et al. Advancement of Sensor Integrated Organ-on-Chip Devices. Sensors 2021, 21, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, M.; Henning, H.; Tol, H.V.; Gadella, B. Oviduct-on-a-Chip: Creating a Niche to Support Physiological Epigenetic Reprogramming During Bovine In Vitro Embryo Production. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Reproduction, Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Odijk, M.; van der Meer, A.D.; Levner, D.; Kim, H.J.; van der Helm, M.W.; Segerink, L.I.; Frimat, J.P.; Hamilton, G.A.; Ingber, D.E.; van den Berg, A. Measuring direct current trans-epithelial electrical resistance in organ-on-a-chip microsystems. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, S.; Lindsey, J.S.; Poudel, I.; Chinthala, S.; Nickerson, M.D.; Gerami-Naini, B.; Gurkan, U.A.; Anchan, R.M.; Demirci, U. Functional maintenance of differentiated embryoid bodies in microfluidic systems: A platform for personalized medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimzadeh, M.; Khashayar, P.; Amereh, M.; Tasnim, N.; Hoorfar, M.; Akbari, M. Microfluidic-Based Oxygen (O2) Sensors for On-Chip Monitoring of Cell, Tissue and Organ Metabolism. Biosensors 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharova, M.; Palma do Carmo, M.A.; van der Helm, M.W.; Le-The, H.; de Graaf, M.N.S.; Orlova, V.; van den Berg, A.; van der Meer, A.D.; Broersen, K.; Segerink, L.I. Multiplexed blood-brain barrier organ-on-chip. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 3132–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combs, D.J.; Moult, E.M.; England, S.K.; Cohen, A.E. Mapping changes in uterine contractility during the ovulatory cycle with wide-area calcium imaging in live mice. bioRxiv 2024, 5, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Cole, T.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.Y. Mechanical Strain-Enabled Reconstitution of Dynamic Environment in Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms: A Review. Micromachines 2021, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, V.; Pensabene, V. Organs-On-Chip Models of the Female Reproductive System. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.E.; Huh, D.D. Organ-on-a-chip technology for the study of the female reproductive system. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 173, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, S. Infectious Vaginitis, Cervicitis, and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 107, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Chacra, L.; Fenollar, F.; Diop, K. Bacterial Vaginosis: What Do We Currently Know? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 672429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.; Doherty, E.; To, T.; Sutherland, A.; Grant, J.; Junaid, A.; Gulati, A.; LoGrande, N.; Izadifar, Z.; Timilsina, S.S.; et al. Vaginal microbiome-host interactions modeled in a human vagina-on-a-chip. Microbiome 2022, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, L.; Nisolle, M. Current Challenges and Future Prospects in Human Reproduction and Infertility. Medicina 2024, 60, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.I.; Taboryski, R. Recent Advances in Microswimmers for Biomedical Applications. Micromachines 2020, 11, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatimel, N.; Perez, G.; Bruno, E.; Sagnat, D.; Rolland, C.; Tanguy-Le-Gac, Y.; Di Donato, E.; Racaud, C.; Léandri, R.; Bettiol, C.; et al. Human fallopian tube organoids provide a favourable environment for sperm motility. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.N.; Moyle-Heyrman, G.; Kim, J.J.; Burdette, J.E. Microphysiologic systems in female reproductive biology. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 1690–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari-Khoei, H.; Esfandiari, F.; Hajari, M.A.; Ghorbaninejad, Z.; Piryaei, A.; Baharvand, H. Organoid technology in female reproductive biomedicine. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2020, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumduri, C.; Turco, M.Y. Organoids of the female reproductive tract. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.E.; Kumar, T.R.; Duncan, F.E. In vitro ovarian follicle growth: A comprehensive analysis of key protocol variables. Biol. Reprod. 2020, 103, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malo, C.; Oliván, S.; Ochoa, I.; Shikanov, A. In Vitro Growth of Human Follicles: Current Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Zhao, Y.; Su, J.; Ryan, D.; Wu, H. Convenient method for modifying poly(dimethylsiloxane) to be airtight and resistive against absorption of small molecules. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 5965–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Chua, Y.C.; Kang, T.G. Oxygen plasma treatment for reducing hydrophobicity of a sealed polydimethylsiloxane microchannel. Biomicrofluidics 2010, 4, 32204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwardt, V.; Ainscough, A.J.; Viswanathan, P.; Sherrod, S.D.; McLean, J.A.; Haddrick, M.; Pensabene, V. Translational Roadmap for the Organs-on-a-Chip Industry toward Broad Adoption. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, J.; Ghanem, A.; Wallisch, P.; Banaeiyan, A.A.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Taškova, K.; Haltmeier, M.; Kurtz, A.; Becker, H.; Reuter, S.; et al. Liver-Kidney-on-Chip To Study Toxicity of Drug Metabolites. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantengco, O.A.G.; Richardson, L.S.; Radnaa, E.; Kammala, A.K.; Kim, S.; Medina, P.M.B.; Han, A.; Menon, R. Exosomes from Ureaplasma parvum-infected ectocervical epithelial cells promote feto-maternal interface inflammation but are insufficient to cause preterm delivery. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 931609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddin, A.; Mustafaoglu, N. Design and Fabrication of Organ-on-Chips: Promises and Challenges. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Feng, L.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X.; Wen, W.; Gong, X. Organ-on-a-chip: Recent breakthroughs and future prospects. Biomed. Eng. Online 2020, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chliara, M.A.; Elezoglou, S.; Zergioti, I. Bioprinting on Organ-on-Chip: Development and Applications. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, H.A.; Eastman, A.J.; Miller, D.R.; Cliffel, D.E. Reproductive organ on-a-chip technologies and assessments of the fetal-maternal interface. Front. Lab A Chip Technol. 2024, 3, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretto, M.; Cox, B.; Noben, M.; Hendriks, N.; Fassbender, A.; Roose, H.; Amant, F.; Timmerman, D.; Tomassetti, C.; Vanhie, A.; et al. Development of organoids from mouse and human endometrium showing endometrial epithelium physiology and long-term expandability. Development 2017, 144, 1775–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, M.; Chen, H.; Deng, K.; Xiao, K. Organ-on-a-Chip Models of the Female Reproductive System: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101125

Pan M, Chen H, Deng K, Xiao K. Organ-on-a-Chip Models of the Female Reproductive System: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. Micromachines. 2025; 16(10):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101125

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Min, Huike Chen, Kai Deng, and Ke Xiao. 2025. "Organ-on-a-Chip Models of the Female Reproductive System: Current Progress and Future Perspectives" Micromachines 16, no. 10: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101125

APA StylePan, M., Chen, H., Deng, K., & Xiao, K. (2025). Organ-on-a-Chip Models of the Female Reproductive System: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. Micromachines, 16(10), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101125