1. Introduction

It has been predicted that the world’s energy consumption will increase by roughly 28% between 2015 and 2040, with residential and commercial buildings’ electricity usage being the major contributor to the growth [

1]. Conventional electricity generation technologies tend to produce carbon dioxide emission, which is believed to be associated with global warming and some other environmental issues. This has led to an urgent need to increase the penetration of renewable energy (RE)-based distributed power generation (DG). In the past decade, the penetration of typical RE-based DG technologies, such as wind power generation and solar photovoltaic (PV) generation, has grown drastically worldwide [

2]. Because of the inherently unpredictable and nonlinear characteristics of these RE-based DG technologies, improvement in energy harvesting and conversion technologies is much desired. Among currently used RE sources, solar PV offers many advantages: it is inexhaustible and pollution-free, and it exhibits the highest energy density, with an average of 170 W/m

2. In addition, solar PV generation systems require relatively low maintenance costs. Increasing the usage of distributed PV systems to a certain level can substantially reduce transmission losses, thus increasing energy utilization. Based on the data reported in [

3], until 2017, the total share of global RE-based generation was only roughly 4%, but it has been expected that the solar PV generation level will catch up in the share of future RE-based generation.

The PV cells in a PV module produce DC electricity out of sunlight. As a result, a proper power converter interface is required for a grid-connected or standalone solar PV generation system when supplying electricity to AC loads. When power converters are tested for practical PV generation applications, environmental conditions such as solar irradiance and ambience temperature have to be considered. Testing the converters under actual and various environmental conditions is a valid yet time-consuming method, and the associated cost may be very high. Moreover, it is also challenging to obtain the current and voltage (I-V) characteristics of a PV module in a laboratory with limited space. A better approach is to design PV emulators using power converters, which require much less space and are easily programmable. In the literature, many PV emulation systems have been reported. In [

4], a buck converter-based PV emulator was controlled using a fast-convergence resistance-feedback strategy that required a current-resistance model of a PV module. A dynamic field programmable analog array (FPAA)-based PV emulator was presented in [

5] with the following advantages: (1) it did not require numerical interpolation or large amount of data in memory; (2) it was easily characterized, compared with a field programmable gate array (FPGA)- or digital signal processor (DSP)-based implementations. In [

6], a portable, inexpensive and light-weight plug-and-play PV emulator was developed using a DC/DC converter. Great promise for PV module emulation with a minimum amount of output error was shown. In [

7], S. M. Azharuddin et al. proposed a near-accurate PV emulator using a simple power converter and a dSPACE controller for real-time control. The proposed device enabled fast converter response with a high bandwidth current regulator. A low-cost, portable, embedded design for implementing a real-time, high-accuracy PV emulator using new processors was proposed in [

8].

For industrial applications, a PV emulator with a higher power rating is required. In [

9], a dynamic 10-kVA PV emulator based on high-power inverters and an active LCL filter was developed and implemented. The maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithms of a real PV module were tested using the proposed hardware. The minimized harmonic current content and fast adjustment for power factor (PF) were achieved with the selected power stage. A. Koran et al. [

10] proposed a high-efficiency PV source simulator with the advantages of using analog and digital-based controllers. A three-phase AC-DC dual boost rectifier cascaded with a three-phase DC-DC interleaved buck converter was used in this system. A low-cost PV module emulation system developed using LabVIEW software was proposed in [

11]. Several analytical models of PV cells and the estimation of power and current curves for a given irradiance and temperature were studied. D. Pelin et al. [

12] described a PV emulator using DC programmable sources and conducted a 6-day emulation. In [

13], a real-time emulator for control and diagnosis purposes of solar PV generation was developed in a Matlab/Simulink environment. I-V characteristics of generator model were emulated with a programmable DC/AC power source. A PV emulator with quasi-sliding mode controller to realize PV characteristics under rapidly varying environmental conditions was proposed in [

14]. In their design case, a user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI) was developed. In [

15], a PV emulator using dSPACE controller with simple control was designed to achieve fast response. Current mode controller and a modified look-up table were combined for the control mechanism.

In most of the papers reviewed above, the theoretical models using V-I curves of the given PV modules and the conventional silicon (Si)-based switching devices were commonly used for designing converter-based PV emulators. In the literature, a conference paper [

16] presented a hardware design case of the PV module emulator, in which GaN MOSFETs were used; however, the details of controller design issues were not discussed. Comprehensive analysis and comparison of performance between Si- and GaN-based DC-DC converters can be found in [

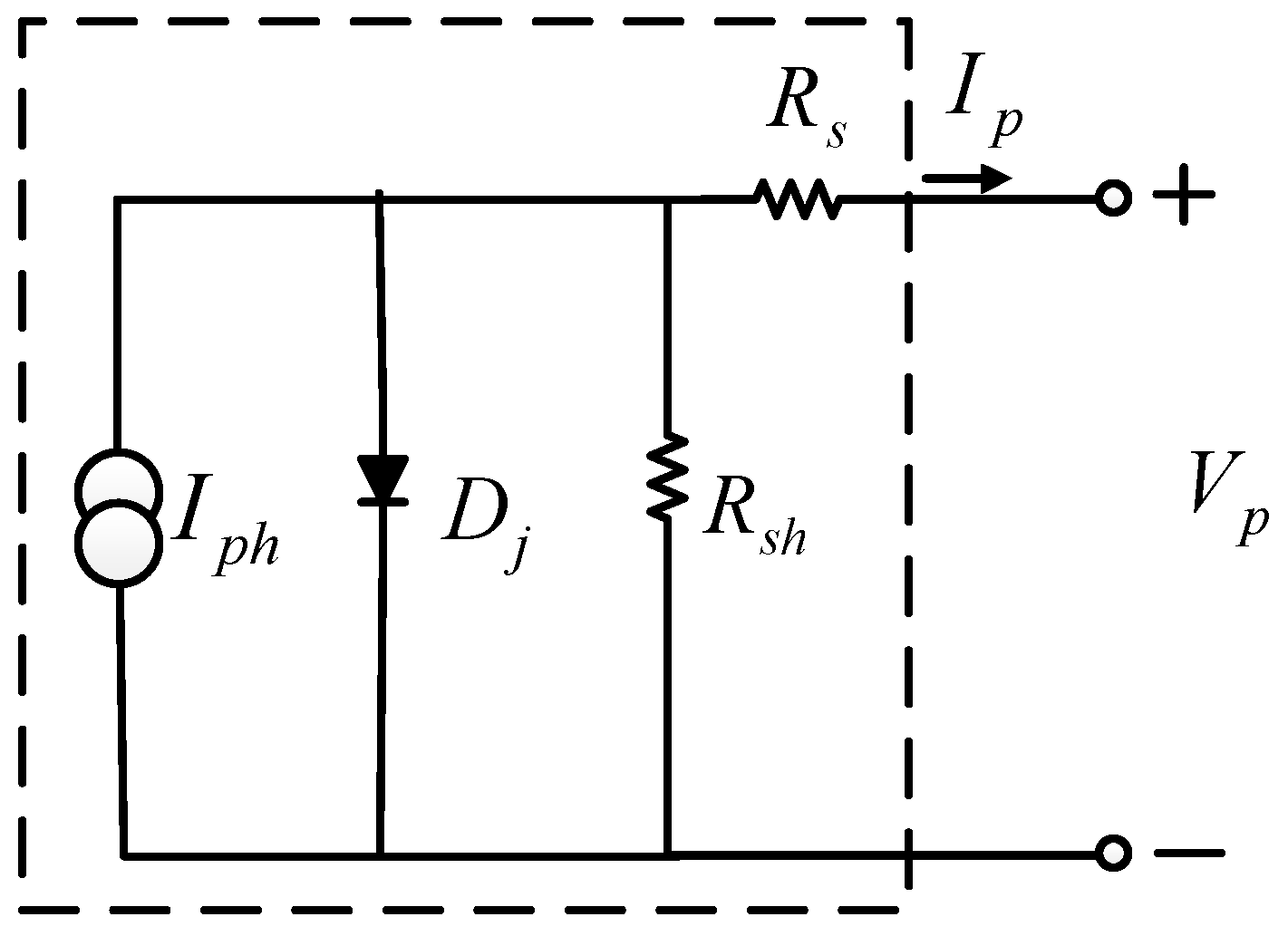

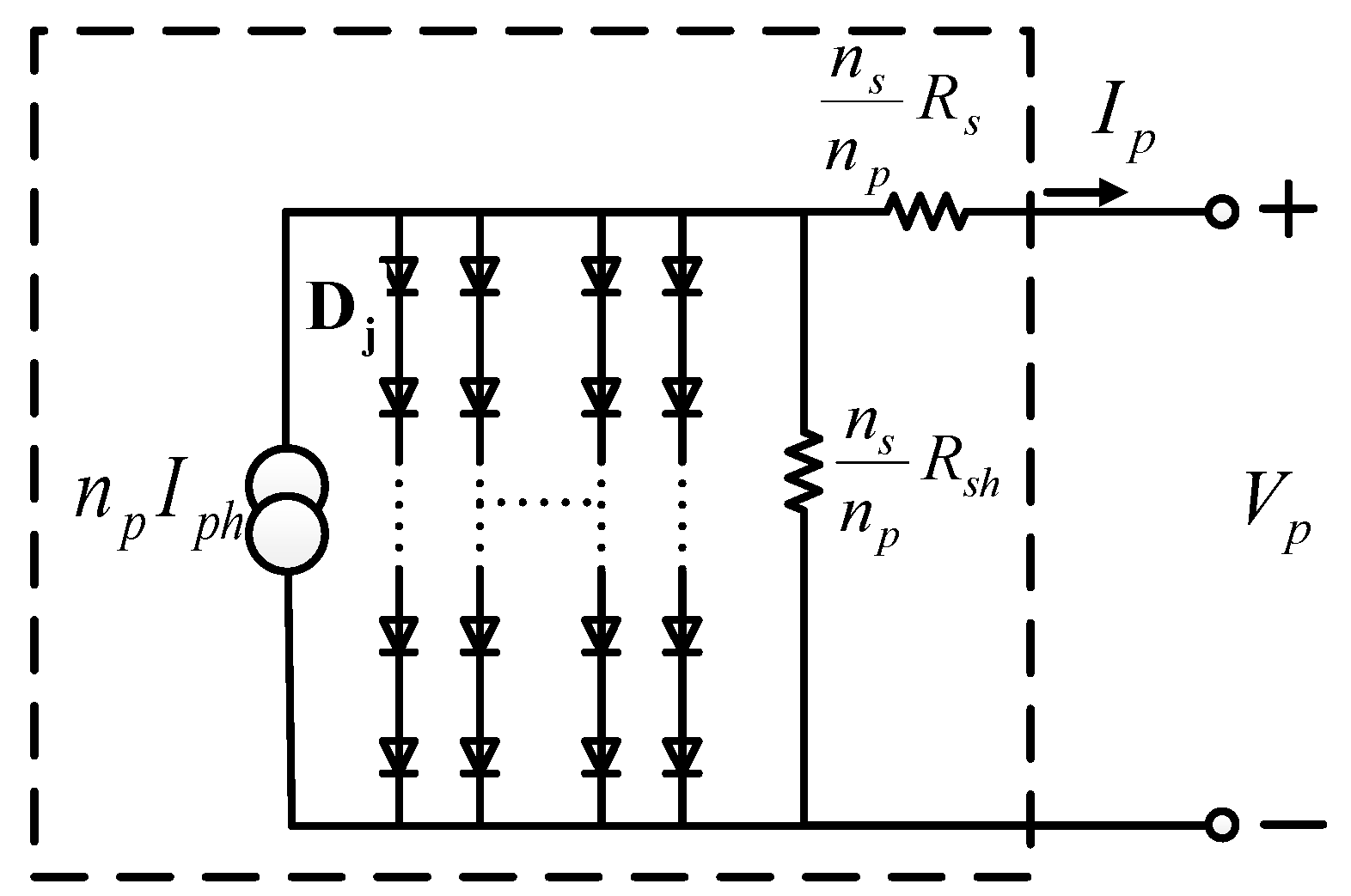

17]. In this paper, a gallium nitride (GaN)-based and DSP-controlled DC-DC converter is presented to achieve a flexible and highly efficient PV emulator with the capability to closely simulate any V-I characteristic of a PV module using parameters either from manufacture’s datasheets or measured data, including normal operating conditions and shading conditions. Flexible emulation features have been implemented with the proposed digital control scheme and verified with a 1 kW hardware prototype. This paper is organized into four sections. In the next section, the PV model is firstly derived, from the cell level to the module level. Then, the modeling of the DC/DC converter and controllers, along with the implementation methodology, are explained.

Section 3 presents results from the simulation and implementation of the proposed emulator with an electronic load to demonstrate the performance of the proposed PV emulator. The test of the system efficiencies of the proposed PV emulator using GaN-based synchronous buck converter operated at different switching frequencies is presented in

Section 4. Finally, a summary of the paper is given in the last section.

3. Simulation and Implementation

To validate the performance of the designed PV emulator, both simulation studies with computer software and hardware implementation are performed.

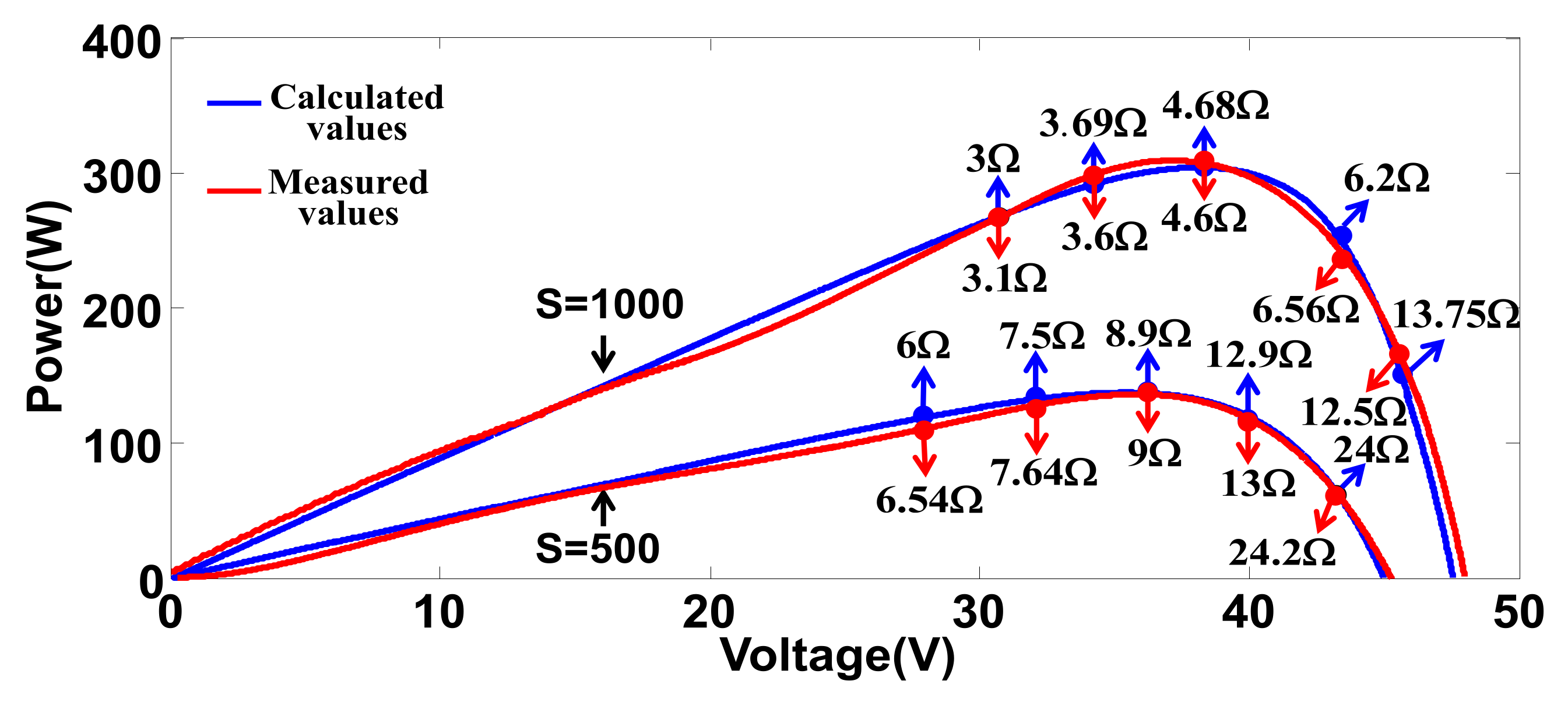

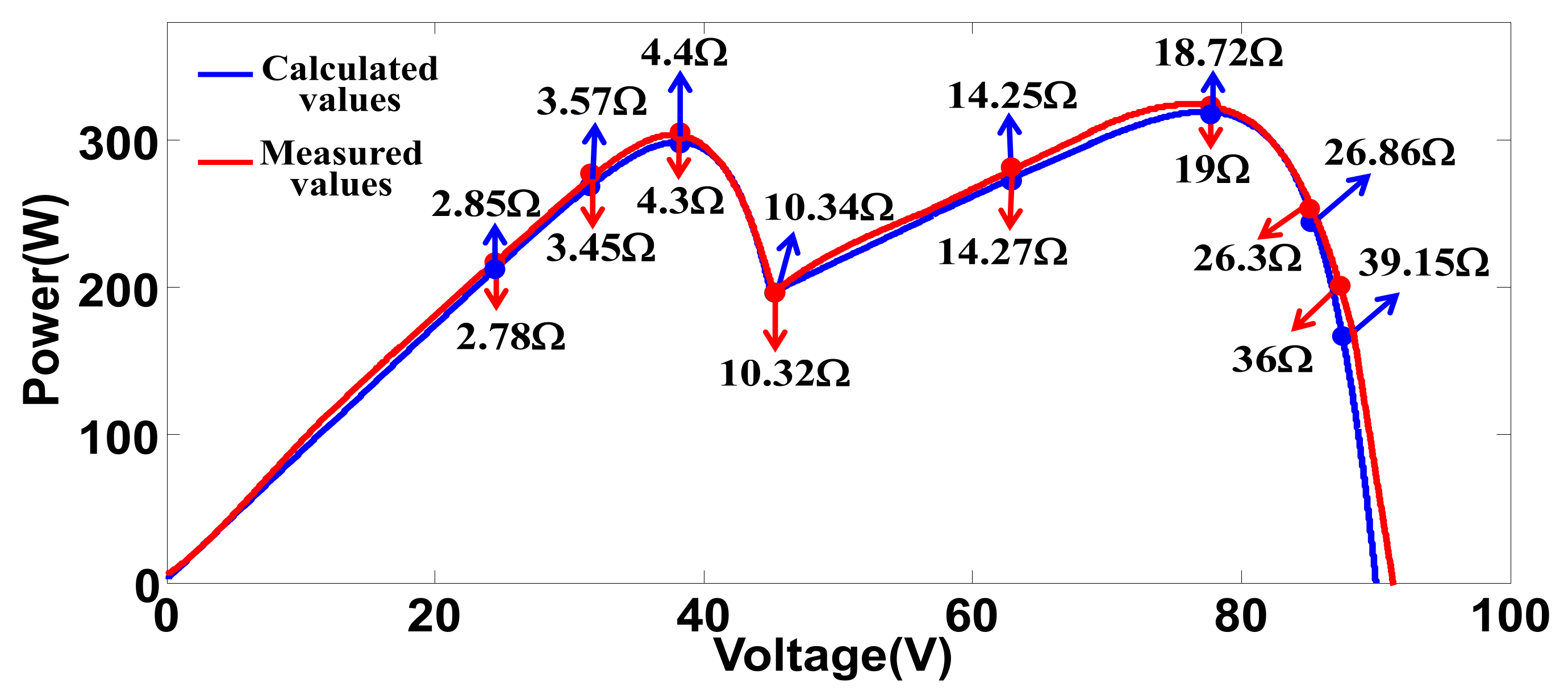

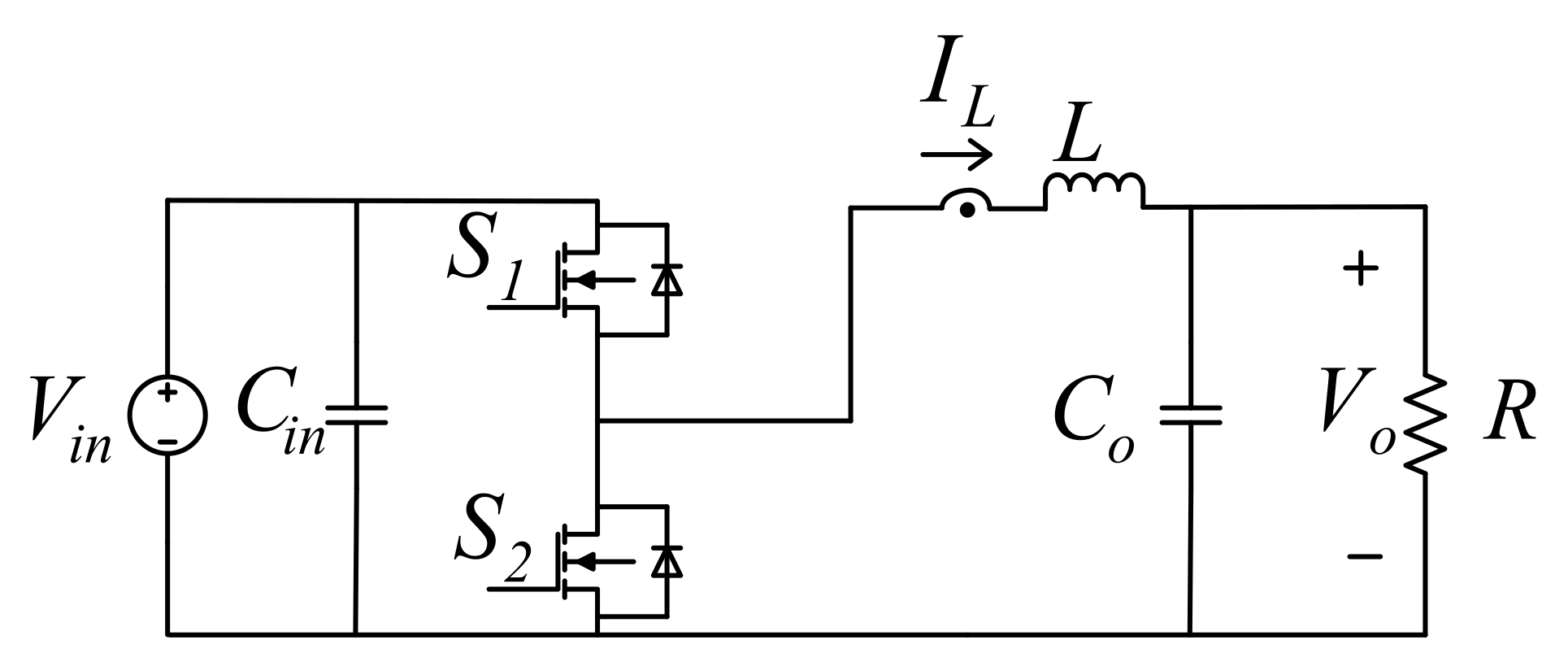

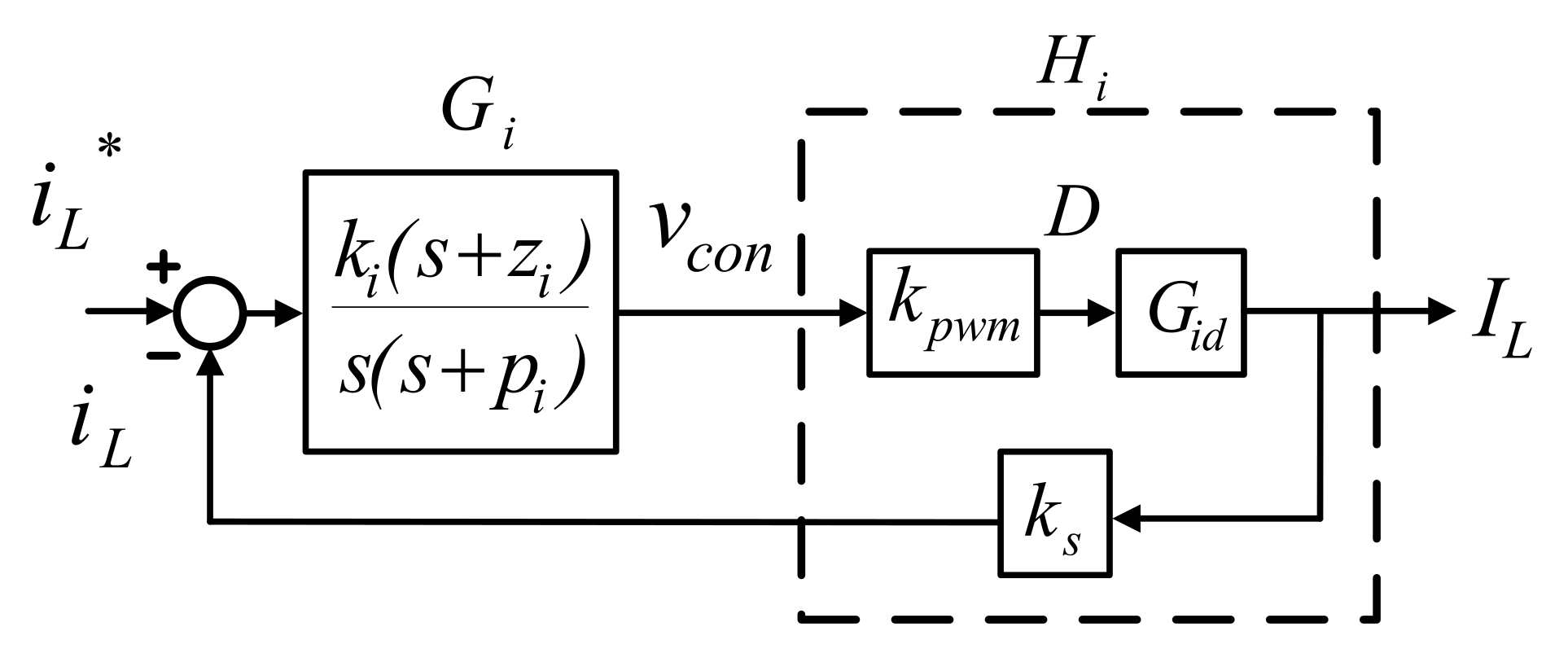

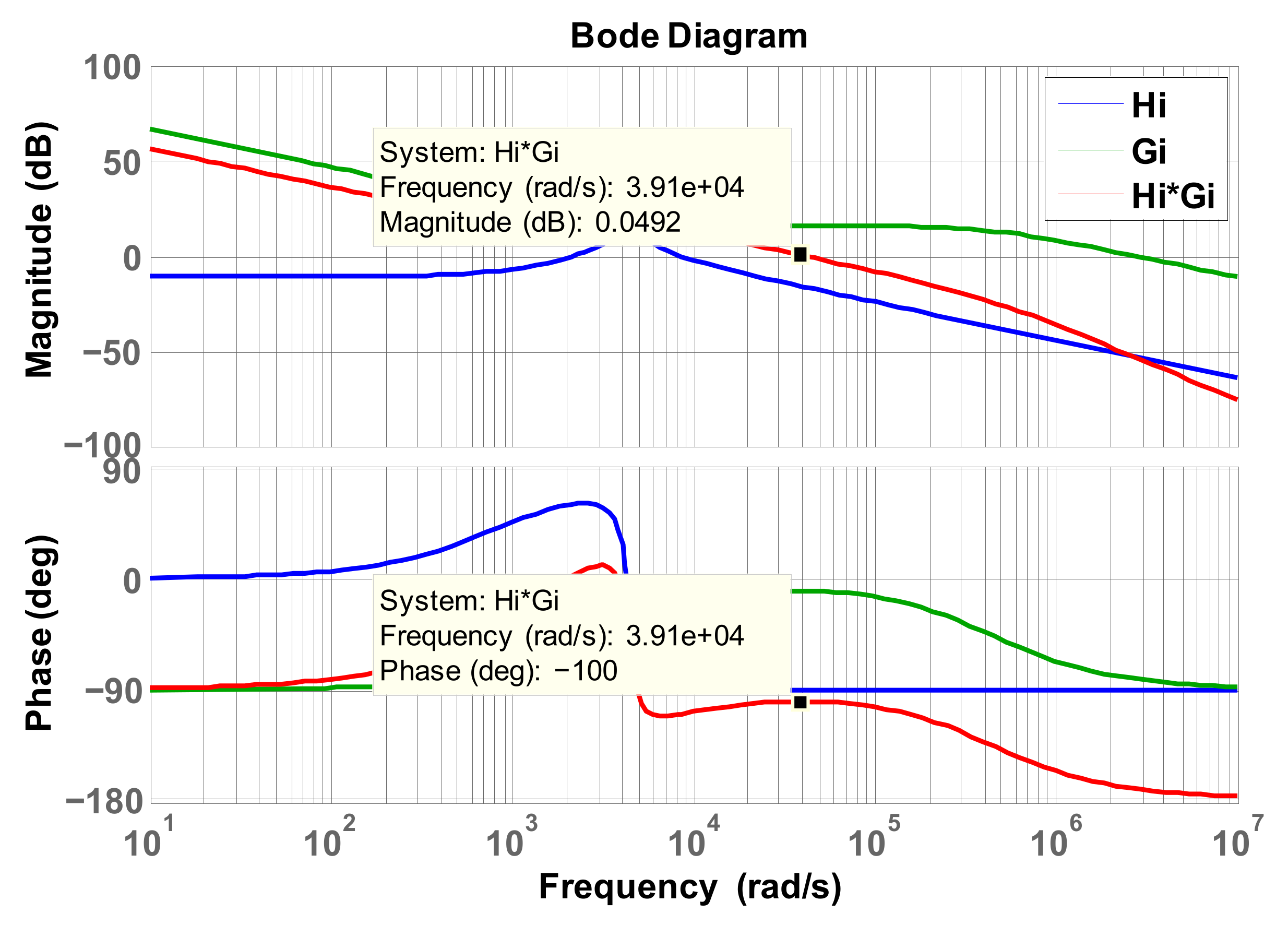

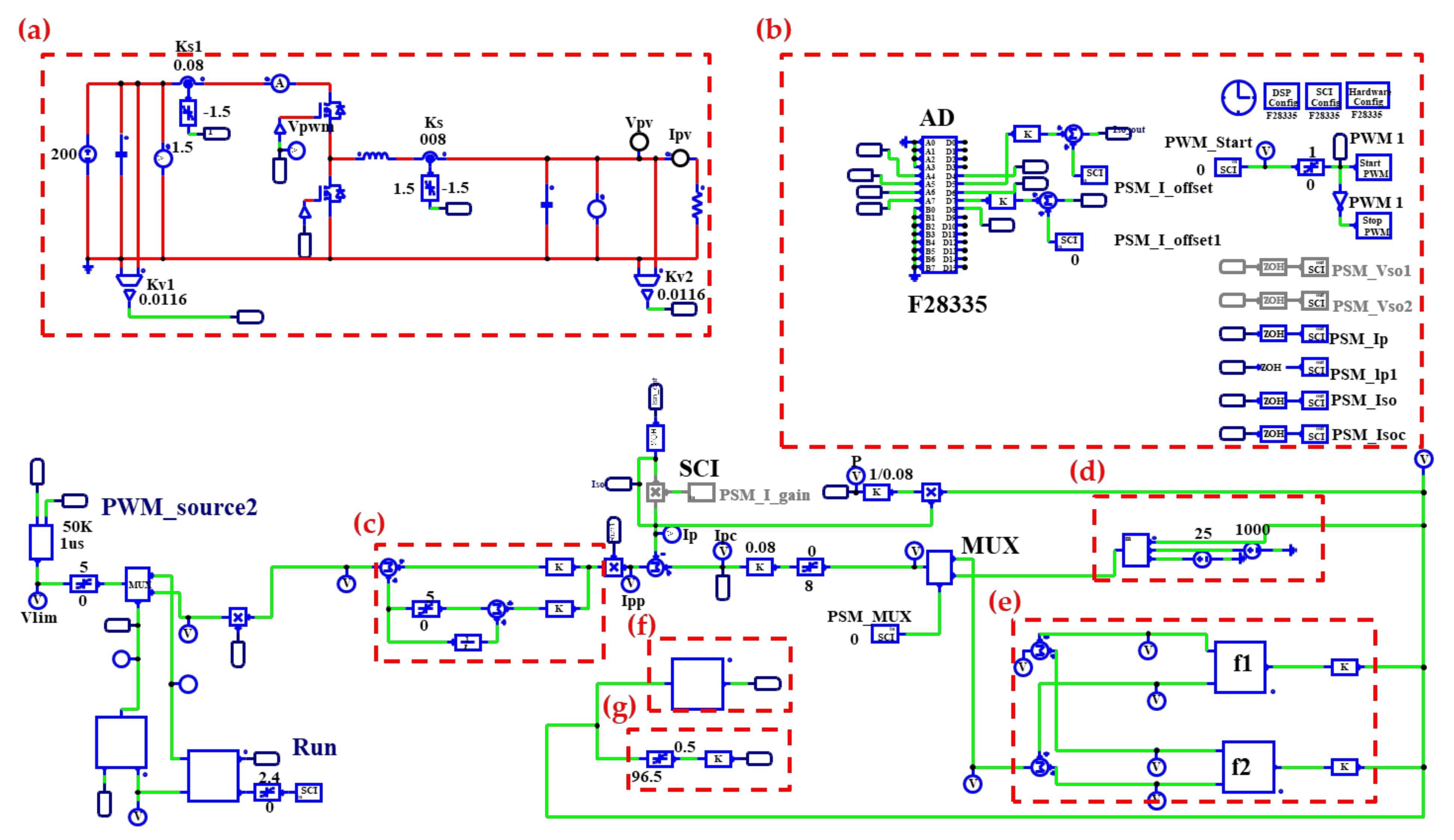

Figure 11 shows the complete software simulation model of the proposed PV emulator and the arrangement of control signals. In this paper, two control methods, the direct referencing method (case 1 and case 2) and output voltage feedback method (case 3), are used to implement the control of the proposed PV emulator with a digital control scheme. In

Figure 11, block (a) is the power circuit of the proposed synchronous buck converter. Block (b) is an analog to digital (AD) module in TI’s DSP. Block (c) is the designed type-II current controller for tracking the current commands sent from PV model blocks (d) or (e). Block (d) is a program block interpreting the theoretical voltage-current relationship of emulated PV module as given in equation (7). Block (e) has two program blocks respectively describing the shedding conditions of two PV modules having different irradiances, e.g., S = 1000 and S = 500. In this study, a simple curve fitting method is used to fit the measured points (V & I pairs) of a given PV module and irradiance condition. In this study case, the number of measured voltage and current data pair is 10. It can be predicted that the measured and theoretically calculated values cannot be perfectly meet. This is due to the inevitable error in curve fitting a limited number of measured points. Some advanced algorithms can be used to improve the quality of fitting but the calculating burden of digital controller will be increased. In block (f), a voltage ramp generator is programmed to send out the emulated terminal voltages of the PV module to the PV model blocks, (e) and (d), for calculating the corresponding currents. As can be seen in

Figure 11, the current commands of the PV emulator can be any combination of the outputs from (d) and (e), depending on the desired emulation scenario. It should be noted that, normally, a properly designed user interface is required for the practical application of the PV emulator; however, it is out of the investigation scope of the present paper.

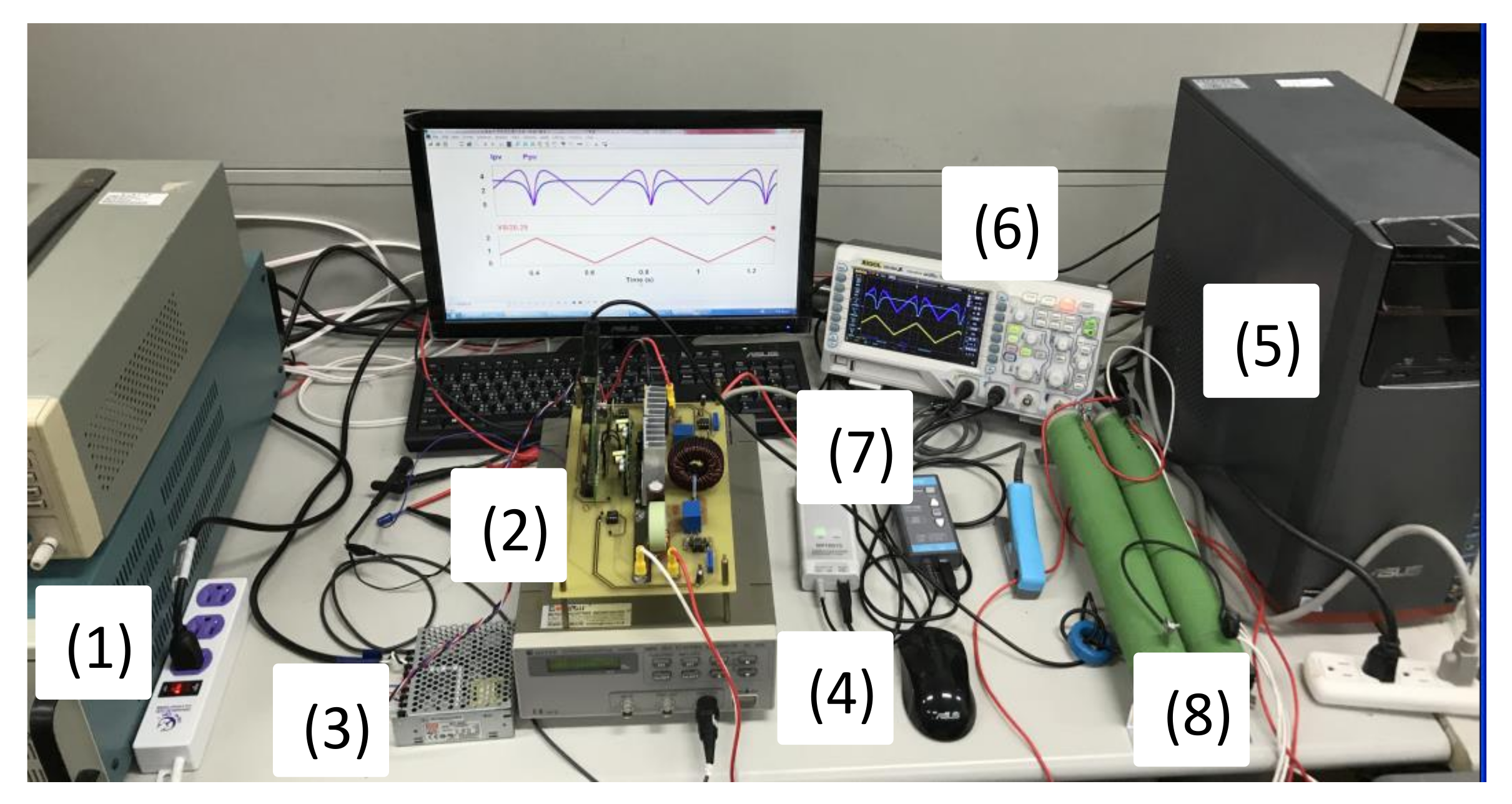

A photo of the complete hardware implementation of the DC-DC synchronous buck converter-based PV module emulator is shown in

Figure 12, including (1) DC power supply, (2) DSP-controlled GaN based synchronous buck converter, (3) auxiliary power, (4) function generator, (5) personal computer, (6) digital oscilloscope, (7) voltage and current probes, and (8) resistive load. The synchronous buck converter is built using GaN power switches (TPH3207WS) with properly designed output inductor and capacitor values. Laboratory-made sensing circuits are used for voltage and current measurements. During operation, sensed current and voltage feedbacks are directly fed into the ADC ports of TI’s TMS320F28335 controller. Corresponding PWM pulses are then sent out via the PWM port. Gate pulses are isolated from the buck converter’s power circuitry with proper driving IC before being applied to the gate of the GaN switches. The major advantage of using DSP and a digital control scheme is online parameter tuning and better flexibility in implementing possible changes of conditions. To verify the effectiveness and performance of the proposed PV emulator, two sets of dynamic V-I characteristics and conditions, i.e., normal irradiance and partial shading conditions, are tested. It is found that the response time of the proposed controller is very short and that the absolute error between experimental results and calculated values is quite small. Typical results are presented in the following paragraphs for comparison.

In case 1, theoretical characteristics of the two PV modules under normal irradiance (S = 1000 & 1000) are used.

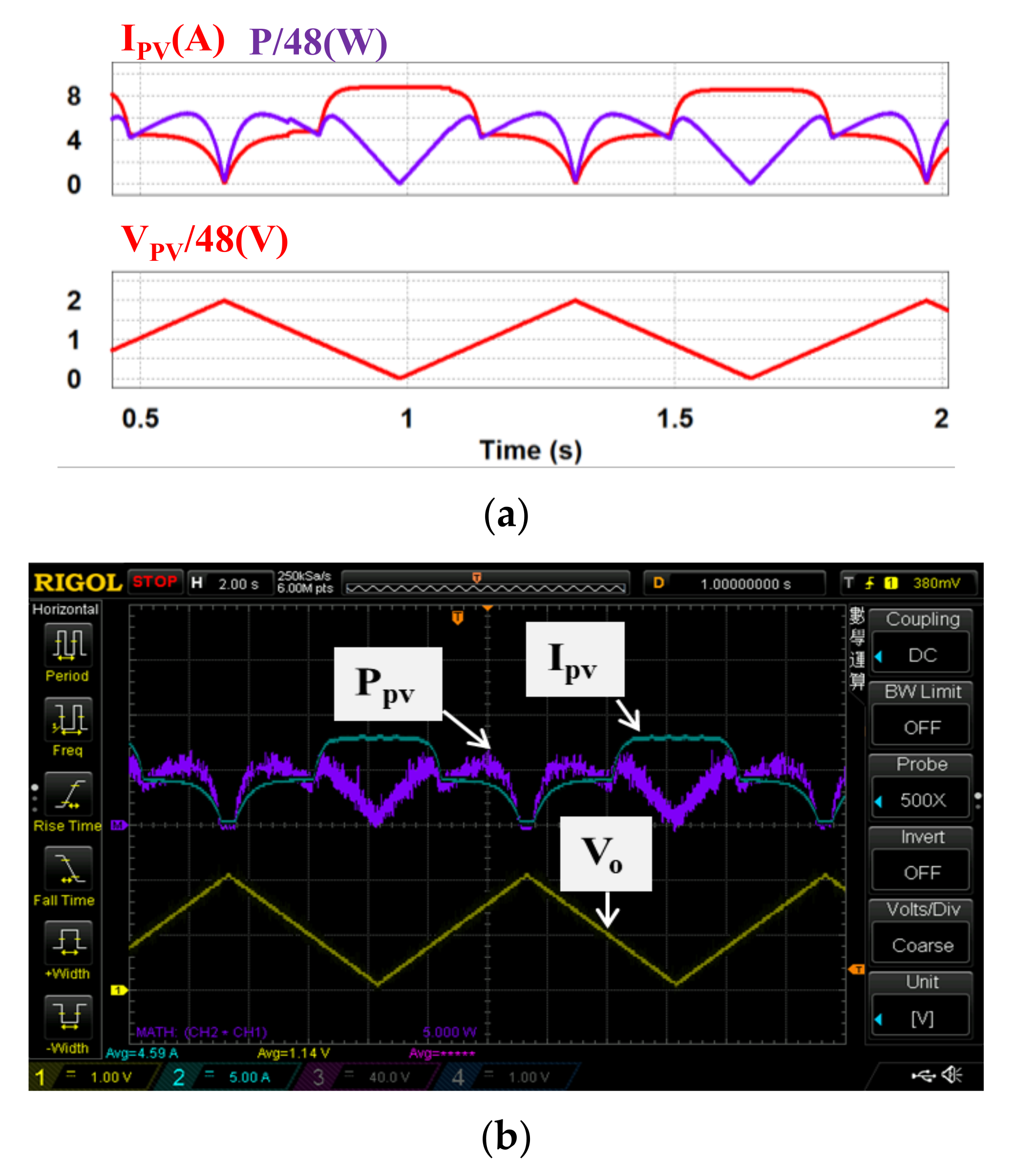

Figure 13a,b shows a set of simulation and measured results from the PV emulator (

IPV: 5 A/div;

Vo: 40 V/div;

T: 2 s/div;

VPV: 48 V/div;

PPV: 270 W/div).

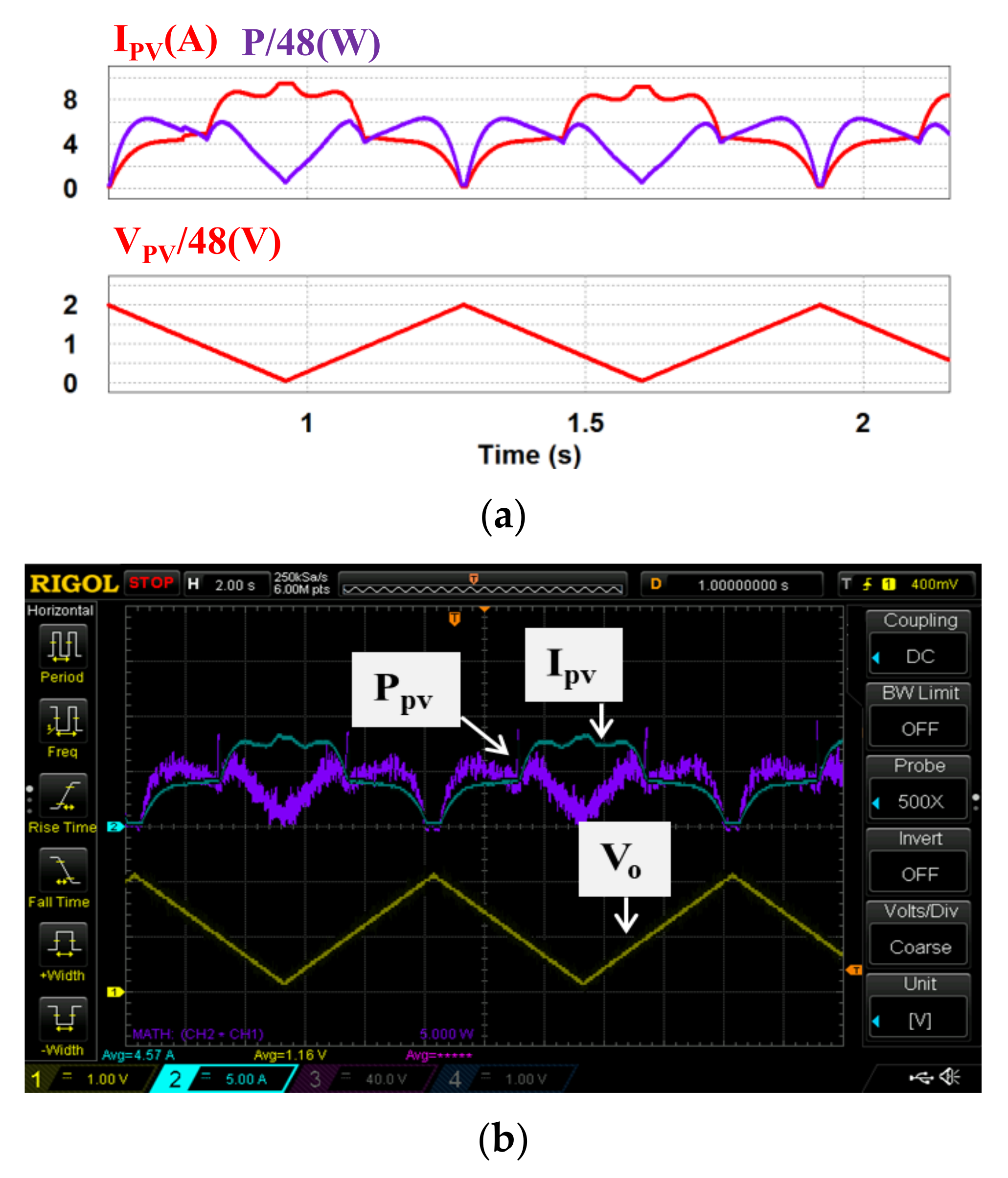

In case 2, both theoretical and measured characteristics of the two PV modules under partial shading (S = 500 & 1000) are used.

Figure 14a,b and

Figure 15a,b respectively show the two sets of simulation and measured results from the proposed PV emulator (

IPV: 5 A/div;

Vo: 40 V/div;

T: 2 s/div;

VPV: 48 V/div;

PPV: 270 W/div).

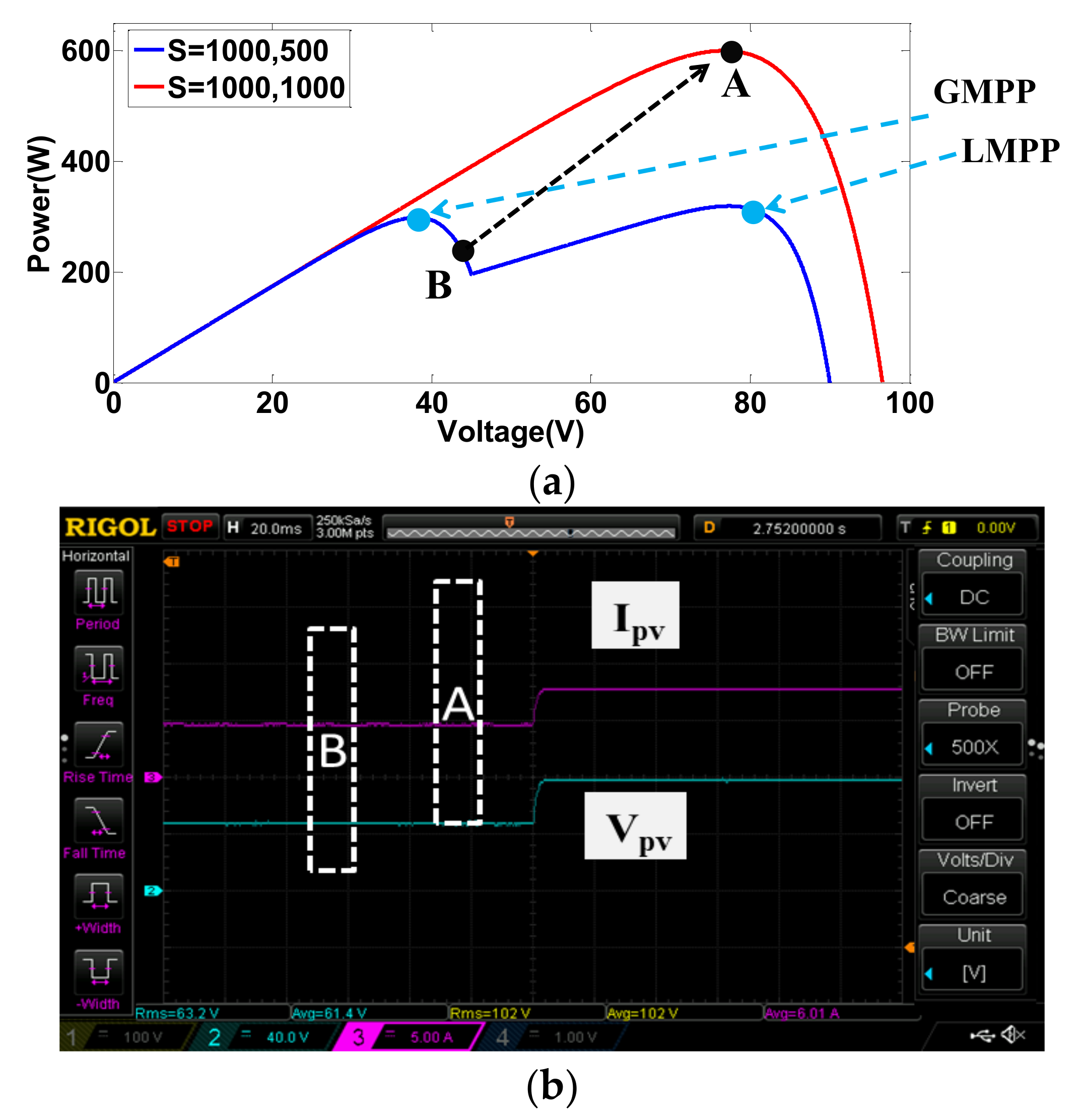

In case 3, the control transition between the conditions of cases 1 and 2 is performed.

Figure 16a shows simulated transition from normal condition (A) to shading condition (B), and

Figure 16b shows the corresponding measured waveforms.

Figure 17 shows the results of control transition from shading condition (B) to normal condition (A) (

IPV: 5 A/div;

Vpv: 40 V/div;

T: 20 ms/div).

As can be seen in

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17, performance in tracking the voltage-current parameters of a given PV module is high. It has been observed that the control error in all test cases is almost negligible. In control practice, the control error can be affected by a number of factors. Typical ones include the type of controller used, the precision of sensors used (the current sensors in this specific design case), the sampling speed, the level of EMI and the quality of the AD device, etc. In this design case, a type II controller, equivalent to a PI controller with a low-pass filter, is utilized to guarantee a theoretical zero-control-error. The accuracy of the Hall current sensor used in our design is about 0.2–1%. To eliminate the 0.2–1% sensing error, a homemade digital compensator is used at the AD configuring module of the TI’s DSP controller with a pre-tuning step.

4. The Analysis of System Efficiency

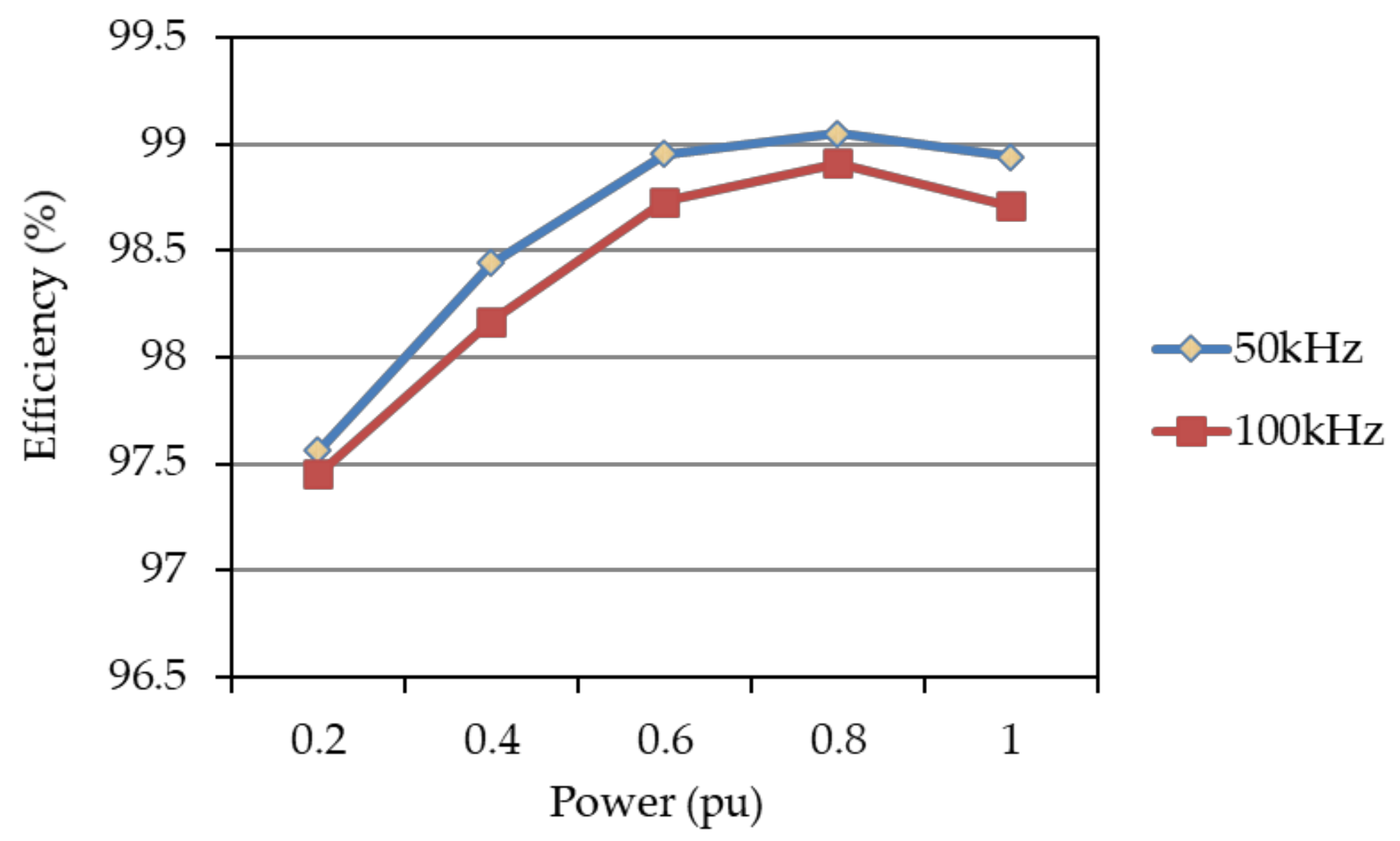

In this paper, the system efficiency of the proposed PV emulator using a GaN-based synchronous buck converter operated at different switching frequencies (50 kHz, 80 kHz) and different output power levels is practically tested.

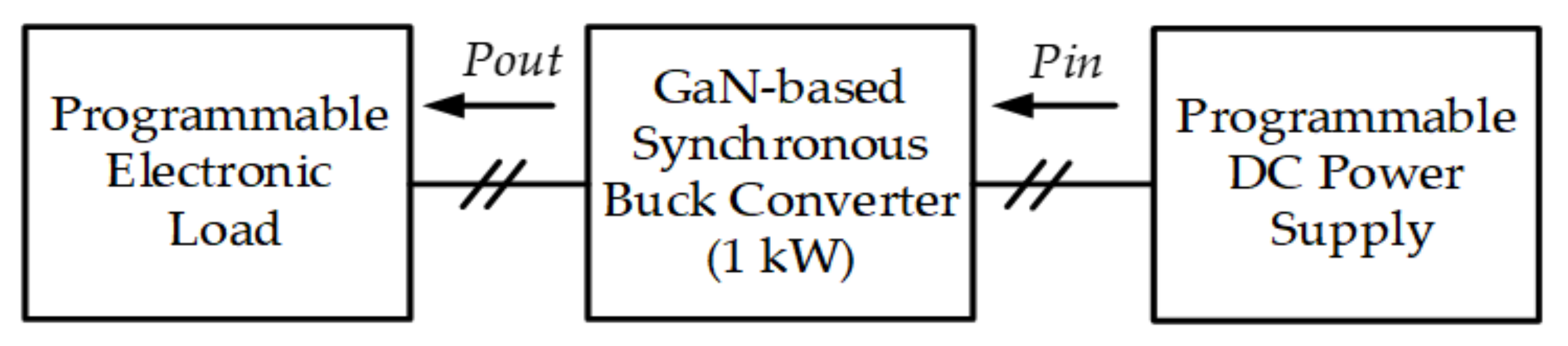

Figure 18 shows the system block diagram of the efficiency tests carried out in this study. In this test, the DC terminals of the proposed GaN-based synchronous buck converter are connected to a programmable DC power supply having the output voltage set to 200 V, and the DC output terminal voltage of the proposed GaN-based synchronous buck converter is regulated at a fixed 100 V by the proposed voltage controller. For testing the converter efficiency under different output power levels, a programmable electronic load is connected to the DC output terminal of the converter. By setting different

Pout and measuring the corresponding

Pin of the converter, the system efficiency at a specific power level and switching frequency can be readily calculated. In this paper, two switching frequencies, i.e., 50 and 80 kHz, are tested at five load levels. The calculated results are graphically shown in

Figure 19. As can be seen in

Figure 19, a maximum efficiency of 99.05% appears at about 80% of the converter’s rated capacity (1 kW), with a switching frequency of 50 kHz, and it is found that, when the switching frequency increases, the efficiency decreases. This is mainly due to the increase in switching losses. In practice, other factors may also affect the performance of efficiency; typical factors include layout construction, the noise level of sensing devices, and driving and control techniques used.