Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword Cross-Targeting the Host as an “Innocent Bystander”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

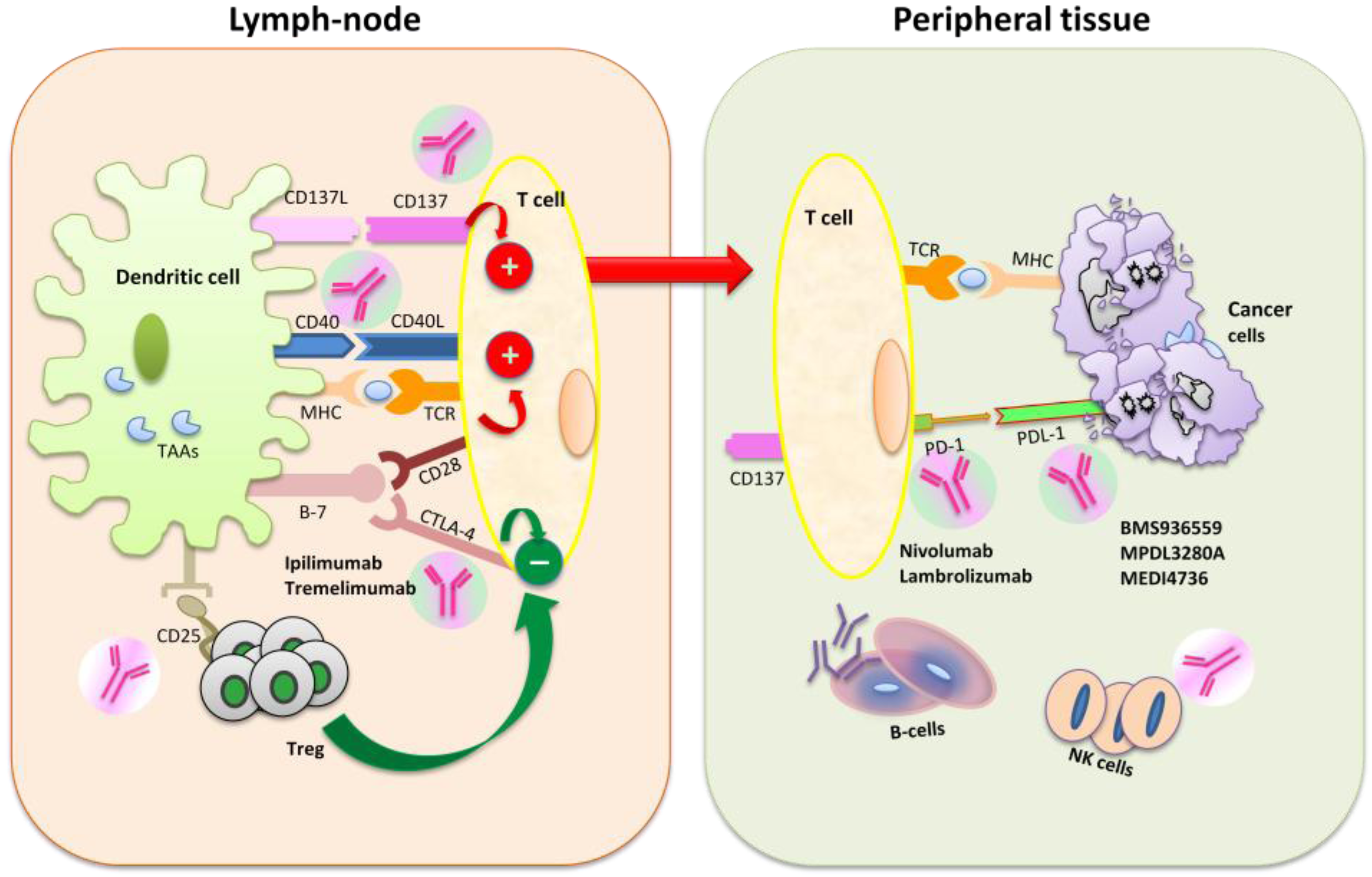

2. Role of Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment

3. Mechanisms of Action of Immunomodulators

4. Clinical Trials with Immune Checkpoint Blockade Targeted Agents

5. Clinical Trials with Immune-Stimulatory and Immune-Suppressor Molecules

| Study drug | National Clinical Trial (NCT) Number | Disease | Therapy | Phase | Primary Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies | |||||

| Ipilimumab | |||||

| NCT01489059 | Melanoma | IL-21 + Ipilimumab | I | Safety | |

| NCT01676649 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab + Carboplatin + Paclitaxel | II | Safety | |

| NCT01498978 | Prostate Cancer | Ipilimumab + Androgen Suppression Therapy | II | Efficacy | |

| NCT01896869 | Pancreatic cancer | FOLFIRINOX Followed by Ipilimumab | II | Efficacy | |

| NCT01363206 | Melanoma | Granulocyte Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor + Ipilimumab | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01988077 | Melanoma | Adoptive T-Cell Transfer + Ipilimumab | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01856023 | Melanoma | IL-2 + Ipilimumab | III | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01822509 | Hematologic Malignancies | Ipilimumab After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation | I | Safety | |

| NCT01611558 | Ovarian Cancer | Ipilimumab | II | Safety | |

| NCT01450761 | Small Cell Lung Cancer | Etoposide + Platinum +/− Ipilimumab | III | Efficacy | |

| NCT01604889 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab +/− INCB024360 | I/II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01024231 | Melanoma | BMS-936558 + Ipilimumab | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01832870 | Prostate Cancer | Sipuleucel-T + Ipilimumab | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01524991 | Urothelial Carcinoma | Gemcitabine, Cisplatin + Ipilimumab | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01285609 | Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Paclitaxel + Carboplatin +/− Ipilimumab | III | Efficacy | |

| NCT01565837 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab + Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01689974 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab vs. Ipilimumab + Radiotherapy | II | response rates | |

| NCT01750983 | Advanced Cancers | Ipilimumab + Lenalidomide | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01489059 | Melanoma | IL-21/Ipilimumab | I | Safety | |

| NCT01740297 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab +/− Talimogene Laherparepvec | I/II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01274338 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab or High-Dose Interferon Alfa-2b | III | Efficacy | |

| NCT01738139 | Advanced Cancers | Ipilimumab +/− Mesylate | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01827111 | Melanoma | Abraxane + Ipilimumab | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01767454 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab + Dabrafenib +/− Trametinib | I | Safety | |

| NCT01860430 | Cancer of Head and Neck | Cetuximab + Radiotherapy + Ipilimumab | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01673854 | Melanoma | Vemurafenib Followed by Ipilimumab | II | Safety | |

| NCT01608594 | Melanoma (Neoadjuvant) | Ipilimumab + IFN-α2b | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01590082 | Melanoma | Doxycycline, Temozolomide + Ipilimumab | I/II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01711515 | Cervical Cancer | Chemoradiation Therapy + Ipilimumab | I | Safety | |

| NCT01810016 | Melanoma | NY-ESO-1 Vaccine + Ipilimumab | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01896999 | Hodgkin Lymphoma | Ipilimumab and Brentuximab Vedotin | I | Safety | |

| NCT01473940 | Pancreatic Cancer | Ipilimumab and Gemcitabine | I | Safety | |

| NCT01729806 | B-Cell Lymphoma | Ipilimumab + Rituximab | I | Safety | |

| NCT01331525 | Small Cell Lung Cancer | Ipilimumab + Carboplatin + Etoposide | II | Efficacy | |

| NCT00836407 | Pancreatic Cancer | Ipilimumab +/− Vaccine Therapy | I | Safety | |

| NCT01643278 | Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors or Other Sarcomas | Dasatinib and Ipilimumab | I | Safety | |

| NCT00636168 | Melanoma | Melanoma vs. placebo | III | Efficacy | |

| Tremelimumab | |||||

| NCT01843374 | Mesothelioma | Tremelimumab vs. Placebo | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01853618 | Liver Cancer | Tremelimumab + Chemoembolization | I | Safety | |

| NCT01975831 | Solid Tumors | MEDI4736 + Tremelimumab | I | Safety | |

| NCT01103635 | Melanoma | Tremelimumab + CP-870,893 | I | Safety | |

| Anti-PD-1 antibodies | |||||

| Nivolumab | |||||

| NCT01783938 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab followed by Nivolumab | II | Safety | |

| NCT01454102 | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | Nivolumab + Chemotherapy or As Maintenance Therapy | I | Safety | |

| NCT01928394 | Solid Tumors | Nivolumab or Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | I/II | Efficacy | |

| NCT01642004 | Squamous Cell Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | Nivolumab vs Docetaxel | III | Efficacy | |

| NCT01844505 NCT01927419 | Melanoma | Nivolumab or Nivolumab + Ipilimumab or Ipilimumab | III/II | Efficacy | |

| NCT01668784 | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Nivolumab vs. Everolimus | III | Efficacy | |

| NCT01968109 | Solid Tumors | Anti-LAG-3 +/− Anti-PD-1 | I | Safety | |

| NCT01592370 | Hematologic Malignancy | Nivolumab | I | Safety | |

| NCT01721772 | Melanoma | Nivolumab vs. Dacarbazine | III | Efficacy | |

| Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies | |||||

| Ipilimumab | |||||

| NCT01629758 | Solid Tumors | IL-21+ Nivolumab | I | Safety | |

| MK-3475 | |||||

| NCT01295827 | Solid Tumor | MK-3475 | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01840579 | Solid Tumor | MK-3475 + chemotherapy | I | Safety | |

| NCT01905657 | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | MK-3475 vs. Docetaxel | II/III | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01866319 | Melanoma | MK-3475 vs. Ipilimumab | III | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01848834 | Solid Tumor | MK-3475 | I | Safety/Efficacy | |

| Anti-PD-L1 antibodies | |||||

| BMS-936559 | |||||

| NCT00729664 | Cancer | BMS-936559 | I | Safety | |

| MPDL3280A | |||||

| NCT01633970 | Solid Tumors | MPDL3280A + Bevacizumab +/− Chemotherapy | I | Safety | |

| NCT01656642 | Melanoma | MPDL3280A + Vemurafenib | I | Safety | |

| NCT01846416 | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | MPDL3280A | II/III | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01903993 | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | MPDL3280A vs. Docetaxel | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| Other immunomodulators | |||||

| BMS-986015 (Anti-KIR) | |||||

| NCT01750580 | Cancer | BMS-986015 + Ipilimumab | I | Safety | |

| Daclizumab (anti CD25) | |||||

| NCT01468311 | Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | Daclizumab | I/II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| NCT01307618 | Melanoma | Vaccine +/− IL-12 Followed by Daclizumab | II | Safety/Efficacy | |

| BMS-663513 (CD137 agonist) | |||||

| NCT01471210 | Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/Solid Tumors | BMS-663513 | I | Safety | |

| NCT01775631 | Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | BMS-663513 + Rituximab | I | Safety | |

6. Immune-Related Toxicity of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

| Serious Adverse Events (Grade 3 and 4) | Ipilimumab [9*,42,72,74,76] | Tremelimumab [44,45,46] | Anti-PD1 (Nivolumab, Lambrolizumab) [3,51 **,52] | Anti-PD-L1 (BMS-936559) [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatologic | ||||

| Rash and/or pruritus | 3.2%–4% | 2.5%–18% | 1%–4% | <1% |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Diarrhea | 4%–5.3% | 5%–21% | 1%–3% | <1% |

| Nausea or vomiting | <5% | 8%–13% | 0 | <1% |

| Colitis | 2%–21% | 2.1%–18% | 2% | |

| Endocrine | ||||

| Hypophysitis | 0.8 | 2% | 1% | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0 | 1% | 1% | 0 |

| Hypopituitarism | 0.8 | 1% | Non reported | 0 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 1.5 | 1% | 0 | <1% |

| Hepatic | ||||

| Increase in alanine aminotransferase | 1.5%–22% | Not reported | 1%–7% | 0 |

| Increase in aspartate aminotransferase | 0.8%–18% | Not reported | 1%–6% | <1% |

| Hepatitis | <3% | 1% | Not reported | <5% |

| Fatigue | 6%–10% | 2%–13% | 2% | 3% |

| Pneumonitis | Not reported | 1% | 1%–3% | Not reported |

7. Toxicity of Other Immunomodulator Agents

8. Toxicity: Management and Correlation with Outcome

9. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smyth, M.J.; Dunn, G.P.; Schreiber, R.D. Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting: The roles of immunity in suppressing tumor development and shaping tumor immunogenicity. Adv. Immunol. 2006, 90, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Loose, D.; Van de Wiele, C. The immune system and cancer. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2009, 24, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaud, C.; John, L.B.; Westwood, J.A. Immune modulation of the tumor microenvironment for enhancing cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e25961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanchot, C.; Terme, M.; Pere, H. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells: Phenotype, role, mechanism of expansion in situ and clinical significance. Cancer Microenviron. 2013, 6, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, G.J.; Fox, S.B.; Han, C.; Leek, R.D.; Garcia, J.F.; Harris, A.L.; Banham, A.H. Quantification of regulatory T cells enables the identification of high-risk breast cancer patients and those at risk of late relapse. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5373–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, E.; Olson, S.H.; Ahn, J. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18538–18543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoual, C.; Hans, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Peyrard, S.; Klein, C.; Agueznay, N.H.; Mosseri, V.; Laccourreye, O.; Bruneval, P.; Fridman, W.H.; Brasnu, D.F.; Tartour, E. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating CD4+ T-cell subpopulations in head and neck cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, D.M.; Droeser, R.A.; Viehl, C.T.; Zlobec, I.; Lugli, A.; Zingg, U.; Oertli, D.; Kettelhack, C.; Terracciano, L.; Tornillo, L. High frequency of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3 (+) regulatory T cells predicts improved survival in mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 2635–2643. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, C.; Thomas, L.; Bondarenko, I.; O'Day, S.; Jeffrey, W.; Garbe, C.; Lebbe, C.; Baurain, J.F.; Testori, A.; Grob, J.J.; et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2517–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Tykodi, S.S.; Chow, L.Q.; Hwu, W.J.; Topalian, S.L.; Hwu, P.; Drake, C.G.; Camacho, L.H.; Kauh, J.; Odunsi, K.; et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaguchi, T.; Sumimoto, H.; Kudo-Saito, C. The mechanisms of cancer immunoescape and development of overcoming strategies. Int. J. Hematol. 2011, 93, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, G.J. Monoclonal antibody mechanisms of action in cancer. Immunol. Res. 2007, 39, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroncek, D.F.; Berger, C.; Cheever, M.A.; Childs, R.W.; Dudley, M.E.; Flynn, P.; Gattinoni, L.; Heath, J.R.; Kalos, M.; Marincola, F.M.; et al. New directions in cellular therapy of cancer: A summary of the summit on cellular therapy for cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 15, 10–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski, T.F. Cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, A.J.; Peggs, K.S.; Allison, J.P. Checkpoint blockade in cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Immunol. 2006, 90, 297–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkord, E.; Alcantar-Orozco, E.M.; Dovedi, S.J.; Hawkins, R.E.; Gilham, D.E.; et al. T regulatory cells in cancer: Recent advances and therapeutic potential. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, R.; Hirohashi, Y.; Sato, N. Depletion of Tregs in vivo: A promising approach to enhance antitumor immunity without autoimmunity. Immunotherapy 2012, 4, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, K.; Gottfried, E.; Kreutz, M.; Mackensen, A. Suppression of Tcell responses by tumor metabolites. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2011, 60, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Pal, S.K.; Reckamp, K.; Figlin, R.A.; Yu, H. STAT3: A target to enhance antitumor immune response. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011, 344, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, M.K.; Wolchok, J.D. At the bedside: CTLA-4- and PD-1-blocking antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.M.; Butterfield, L.H.; Tarhini, A.A.; Zarour, H.; Kalinski, P.; Ferrone, S. Immunotherapy of cancer in 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, S.; Czuczman, M.S.; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, F.J. Dacetuzumab, a humanized mAb against CD40 for the treatment of hematological malignancies. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 10, 579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, A.G.; Hodgkin, P.D. Activation rules: The two-signal theories of immune activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2000, 2, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Peggs, K.S.; Quezada, S.A.; Chambers, C.A.; Korman, A.J.; Allison, J.P. Blockade of CTLA-4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsley, P.S.; Bradshaw, J.; Greene, J.; Peach, R.; Bennett, K.L.; Mittler, R.S. Intracellular trafficking of CTLA-4 and focal localization towards sites of TCR engagement. Immunity 1996, 4, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.B.; Allison, J.P. The emerging role of CTLA-4 as an immune attenuator. Immunity 1997, 7, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, M.L.; Fallarino, F. Mechanisms of CTLA-4-Ig in tolerance induction. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Tagami, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Uede, T.; Shimizu, J.; Sakaguchi, N.; Mak, T.W.; Sakaguchi, S. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.B.; Postow, M.A.; Callahan, M.K.; Allison, J.P.; Wolchok, J.D. Immune Modulation in Cancer with Antibodies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2014, 65, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyi, C.; Postow, M.A. Checkpoint blocking antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Okazaki, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakatani, K.; Hara, M.; Matsumori, A.; Sasayama, S.; Mizoguchi, A.; Hiai, H.; Minato, N.; et al. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science 2001, 5502, 319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, H.; Nose, M.; Hiai, H.; Minato, N.; Honjo, T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity 1999, 11, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parham, P. MHC class I molecules and KIRs in human history, health and survival. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznol, M.; Hodi, F.S.; Margolin, K. Phase I study of BMS-663513, a fully human anti-CD137 agonist monoclonal antibody, in patients (pts) with advanced cancer (CA). J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26 (Suppl. S15), Abstract 3007. [Google Scholar]

- Fonsatti, E.; Maio, M.; Altomonte, M.; Hersey, P. Biology and clinical applications of CD40 in cancer treatment. Semin. Oncol. 2010, 37, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, M.L.; Shiels, H.; Thompson, C.B.; Gajewski, T.F. Expression and function of CTLA-4 in Th1 and Th2 cells. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar]

- Slovin, S.F.; Higano, C.S.; Hamid, O.; Tejwani, S.; Harzstark, A.; Alumkal, J.J.; Scher, H.I.; Chi, K.; Gagnier, P.; McHenry, M.B.; et al. Ipilimumab alone or in combination with radiotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Results from an open-label, multicenter phase I/II study. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genova, C.; Rijavec, E.; Barletta, G.; Sini, C.; Dal Bello, M.G.; Truini, M.; Murolo, C.; Pronzato, P.; Grossi, F. Ipilimumab (MDX-010) in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal, R.E.; Levy, C.; Turner, K.; Mathur, A.; Hughes, M.; Kammula, U.S.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Yang, J.C.; Lowy, I.; et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. 2010, 33, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Hughes, M.; Kammula, U.; Royal, R.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Suri, K.B.; Levy, C.; Allen, T.; Mavroukakis, S.; et al. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J. Immunother. 2007, 30, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 26 February 2014).

- Ribas, A. Clinical development of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody tremelimumab. Semin. Oncol. 2010, 37, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, L.H.; Antonia, S.; Sosman, J.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Gajewski, T.F.; Redman, B.; Pavlov, D.; Bulanhagui, C.; Bozon, V.A.; Gomez-Navarro, J.; Ribas, A. Phase I/II trial of tremelimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Kefford, R.; Marshall, M.A.; Punt, C.J.; Haanen, J.B.; Marmol, M.; Garbe, C.; Gogas, H.; Schachter, J.; Linette, G.; et al. Phase III randomized clinical trial comparing tremelimumab with standard-of-care chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, C.; Elkord, E.; Burt, D.J.; O'Dwyer, J.F.; Austin, E.B.; Stern, P.L.; Hawkins, R.E.; Thistlethwaite, F.C. Modulation of lymphocyte regulation for cancer therapy: A phase II trial of tremelimumab in advanced gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 1662–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatloukal, P.; Heo, D.S.; Park, K.; Kang, J.; Butts, C.; Bradford, D.; Graziano, S.; Huang, B.; Healey, D. Randomized phase II clinical trial comparing tremelimumab (CP-675,206) with best supportive care (BSC) following firstline platinum-based therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 8071. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.Y.; Gore, I.; Fong, L.; Venook, A.; Beck, S.B.; Dorazio, P.; Criscitiello, P.J.; Healey, D.I.; Huang, B.; Gomez-Navarro, J.; et al. Phase II study of the anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 monoclonal antibody, tremelimumab, in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3485–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznol, M.; Kluger, H.M.; Hodi, F.S.; McDermott, D.F.; Carvajal, R.D.; Lawrence, D.P.; Topalian, S.L.; Atkins, M.B.; Powderly, J.D.; Sharfman, W.H.; et al. Survival and long-term follow-up of safety and response in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma (MEL) in a phase I trial of nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538). J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31. 2013: CRA9006. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.K.; Hwu, W.J.; Kefford, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Joseph, R.W.; Weber, J.S.; Dronca, R.; Gangadhar, T.C.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Daud, A.; Hodi, F.S.; Hwu, W.J.; Kefford, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Hersey, P.; Joseph, R.W.; Weber, J.S.; et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Omiya, R.; Matsumura, Y.; Sakoda, Y.; Kuramasu, A.; Augustine, M.M.; Yao, S.; Tsushima, F.; Narazaki, H.; Anand, S.; et al. B7-H1/CD80 interaction is required for the induction and maintenance of peripheral T-cell tolerance. Blood 2010, 116, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Gordon, M.S.; Fine, G.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Soria, J.-C.; Hamid, O.; Powderly, J.D.; Burris, H.A.; Mokatrin, A.; Kowanetz, M.; et al. A study of MPDL3280A, an engineered PD-L1 antibody in patients with locally advanced or metastatic tumors. In Proceedings of the 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 31 May 2013–4 June 2013.

- Tabernero, J.; Powderly, J.D.; Hamid, O.; Gordon, M.S.; Fisher, G.A.; Braiteh, F.S.; Garbo, L.E.; Fine, G.D.; Kowanetz, M.; McCall, B.; et al. Clinical activity, safety, and biomarkers of MPDL3280A, an engineered PD-L1 antibody in patients with locally advanced or metastatic CRC, gastric cancer (GC), SCCHN, or other tumors. In Proceedings of the 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 31 May–4 June 2013.

- Uyttenhove, C.; Pilotte, L.; Theate, I.; Stroobant, V.; Colau, D.; Parmentier, N.; Boon, T.; Van den Eynde, B.J. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasku, M.A.; Clem, A.L.; Telang, S.; Taft, B.; Gettings, K.; Gragg, H.; Cramer, D.; Lear, S.C.; McMasters, K.M.; Miller, D.M.; et al. Transient T cell depletion causes regression of melanoma metastases. J. Transl. Med. 2008, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, A.J.; Vonderheide, R.H. Clinical use of anti-CD25 antibody daclizumab to enhance immune responses to tumor antigen vaccination by targeting regulatory T cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1174, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Phase II, 2nd Line Melanoma: RAND Monotherapy. Available online: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00612664 (accessed on 26 February 2014).

- Curti, B.D.; Kovacsovics-Bankowski, M.; Morris, N.; Walker, E.; Chisholm, L.; Floyd, K.; Walker, J.; Gonzalez, I.; Meeuwsen, T.; Fox, B.A.; et al. OX40 is a potent immune-stimulating target in late-stage cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 7189–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaehler, K.C.; Piel, S.; Livingstone, E.; Schilling, B.; Hauschild, A.; Schadendorf, D. Update on immunologic therapy with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in melanoma: Identification of clinical and biological response patterns, immune-related adverse events, and their management. Semin. Oncol. 2010, 37, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.R.; Krummel, M.F.; Allison, J.P. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science 1996, 271, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Van Elsas, A.; Hurwitz, A.A.; Allison, J.P. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriello, F.; Schweitzer, A.N.; Lynch, W.P.; Bluestone, J.A.; Sharpe, A.H. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity 1995, 3, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, P.; Penninger, J.M.; Timms, E.; Wakeham, A.; Shahinian, A.; Lee, K.P.; Thompson, C.B.; Griesser, H.; Mak, T.W. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science 1995, 270, 985–988. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz, A.A.; Sullivan, T.J.; Krummel, M.F.; Sobel, R.A.; Allison, J.P. Specific blockade of CTLA-4/B7 interactions results in exacerbated clinical and histologic disease in an actively induced model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 1997, 73, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, P.J.; Maldonado, J.H.; Davis, T.A.; June, C.H.; Racke, M.K. CTLA-4 blockade enhances clinical disease and cytokine production during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 1996, 157, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Luhder, F.; Hoglund, P.; Allison, J.P.; Benoist, C.; Mathis, D. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) regulates the unfolding of autoimmune diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 187, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, A.A.; Foster, B.A.; Kwon, E.D.; Truong, T.; Choi, E.M.; Greenberg, N.M.; Burg, M.B.; Allison, J.P. Combination immunotherapy of primary prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse model using CTLA-4 blockade. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 2444–2448. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, G.Q.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Hwu, P.; Topalian, S.L.; Schwartzentruber, D.J.; Restifo, N.P.; Haworth, L.R.; Seipp, C.A.; Freezer, L.J.; et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8372–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maker, A.V.; Phan, G.Q.; Attia, P.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Kammula, U.S.; Royal, R.E.; Haworth, L.R.; Levy, C.; et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity in patients treated with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and interleukin 2: A phase I/II study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2005, 12, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.S.; Kahler, K.C.; Hauschild, A. Management of immune related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, H.; Wilson, K.S. Immune toxicities and long remission duration after ipilimumab therapy for metastatic melanoma: Two illustrative cases. Curr. Oncol. 2013, 20, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, K.E.; Blansfield, J.A.; Tran, K.Q.; Feldman, A.L.; Hughes, M.S.; Royal, R.E.; Kammula, U.S.; Topalian, S.L.; Sherry, R.M.; Kleiner, D.; et al. Enterocolitis in patients after antibody blockade of CTLA-4. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoos, A.; Ibrahim, R.; Korman, A.; Abdallah, K.; Berman, D.; Shahabi, V.; Chin, K.; Canetta, R.; Humphrey, R.; et al. Development of ipilimumab: Contribution to a new paradigm for cancer immunotherapy. Semin. Oncol. 2010, 37, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, L.; Small, E.J. Anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 antibody: The first in an emerging class of immunomodulatory antibodies for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5275–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Weber, J.S. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: A multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist 2013, 18, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Soria, J.C.; Eggermont, A.M. Drug of the year: Programmed death-1 receptor/programmed death-1 ligand-1 receptor monoclonal antibodies. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 2968–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Strahotin, S.; Hewes, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Archer, D.; Spencer, T.; Dillehay, D.; Kwon, B.; Chen, L.; et al. Cytokine-mediated disruption of lymphocyte trafficking, hemopoiesis, and induction of lymphopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia in anti-CD137-treated mice. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 4194–4213. [Google Scholar]

- Ascierto, P.A.; Simeone, E.; Sznol, M.; Fu, Y.X.; Melero, I. Clinical experiences with anti-CD137 and anti-PD1 therapeutic antibodies. Semin. Oncol. 2010, 37, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Berenson, J.R.; Niesvizky, R.; Munshi, N.; Matous, J.; Sobecks, R.; Harrop, K.; Drachman, J.G.; Whiting, N. A phase I multidose study of dacetuzumab (SGN-40; humanized anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody) in patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2010, 95, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, R.R.; Forero-Torres, A.; Shustov, A.; Drachman, J.G. A phase I study of dacetuzumab (SGN-40, a humanized anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2010, 51, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, R.; Forero-Torres, A.; Furman, R.R.; Rosenblatt, J.D.; Younes, A.; Ren, H.; Harrop, K.; Whiting, N.; Drachman, J.G. Phase I study of the humanized anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody dacetuzumab in refractory or recurrent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4371–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, A.J.; Mick, R.; Martin, S.; Recio, A.; Aqui, N.A.; Powell, D.J., Jr.; Colligon, T.A.; Trosko, J.A.; Leinbach, L.I.; Pletcher, C.H.; et al. CD25 blockade depletes and selectively reprograms regulatory T cells in concert with immunotherapy in cancer patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 134–162. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, S.G.; Klapper, J.A.; Smith, F.O.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Royal, R.E.; Kammula, U.S.; Hughes, M.S.; Allen, T.E.; Levy, C.L.; et al. Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 6681–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pages, C.; Gornet, J.M.; Monsel, G.; Allez, M.; Bertheau, P.; Bagot, M.; Lebbé, C.; Viguier, M. Ipilimumab-induced acute severe colitis treated by infliximab. Melanoma Res. 2013, 23, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristol-MyersSquibb. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategy for Yervoy (Ipilimumab) on the risks of and recommended management for severe immune-mediated adverse reaction. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UCM249435.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2014).

- Lutzky, J.; Wolchok, J.; Hamid, O.; Lebbe, L.; Pehamberger, H.; Linette, G.; de Pril, V.; Ibrahim, R.; Hoos, A.; O'Day, S. Association between immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and disease control or overall survival in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma treated with 10 mg/kg ipilimumab in three phase II clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27. 2009: 9034. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.; Thompson, J.A.; Hamid, O.; Lebbe, C.; Pehamberger, H.; Linette, G.; de Pril, V.; Ibrahim, R.; Hoos, A.; O’Day, S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5591–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Gelao, L.; Criscitiello, C.; Esposito, A.; Goldhirsch, A.; Curigliano, G. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword Cross-Targeting the Host as an “Innocent Bystander”. Toxins 2014, 6, 914-933. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6030914

Gelao L, Criscitiello C, Esposito A, Goldhirsch A, Curigliano G. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword Cross-Targeting the Host as an “Innocent Bystander”. Toxins. 2014; 6(3):914-933. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6030914

Chicago/Turabian StyleGelao, Lucia, Carmen Criscitiello, Angela Esposito, Aron Goldhirsch, and Giuseppe Curigliano. 2014. "Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword Cross-Targeting the Host as an “Innocent Bystander”" Toxins 6, no. 3: 914-933. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6030914

APA StyleGelao, L., Criscitiello, C., Esposito, A., Goldhirsch, A., & Curigliano, G. (2014). Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword Cross-Targeting the Host as an “Innocent Bystander”. Toxins, 6(3), 914-933. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6030914