Plasma Metabolomics Reveals Systemic Metabolic Remodeling in Early-Lactation Dairy Cows Fed a Fusarium-Contaminated Diet and Supplemented with a Mycotoxin-Deactivating Product

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

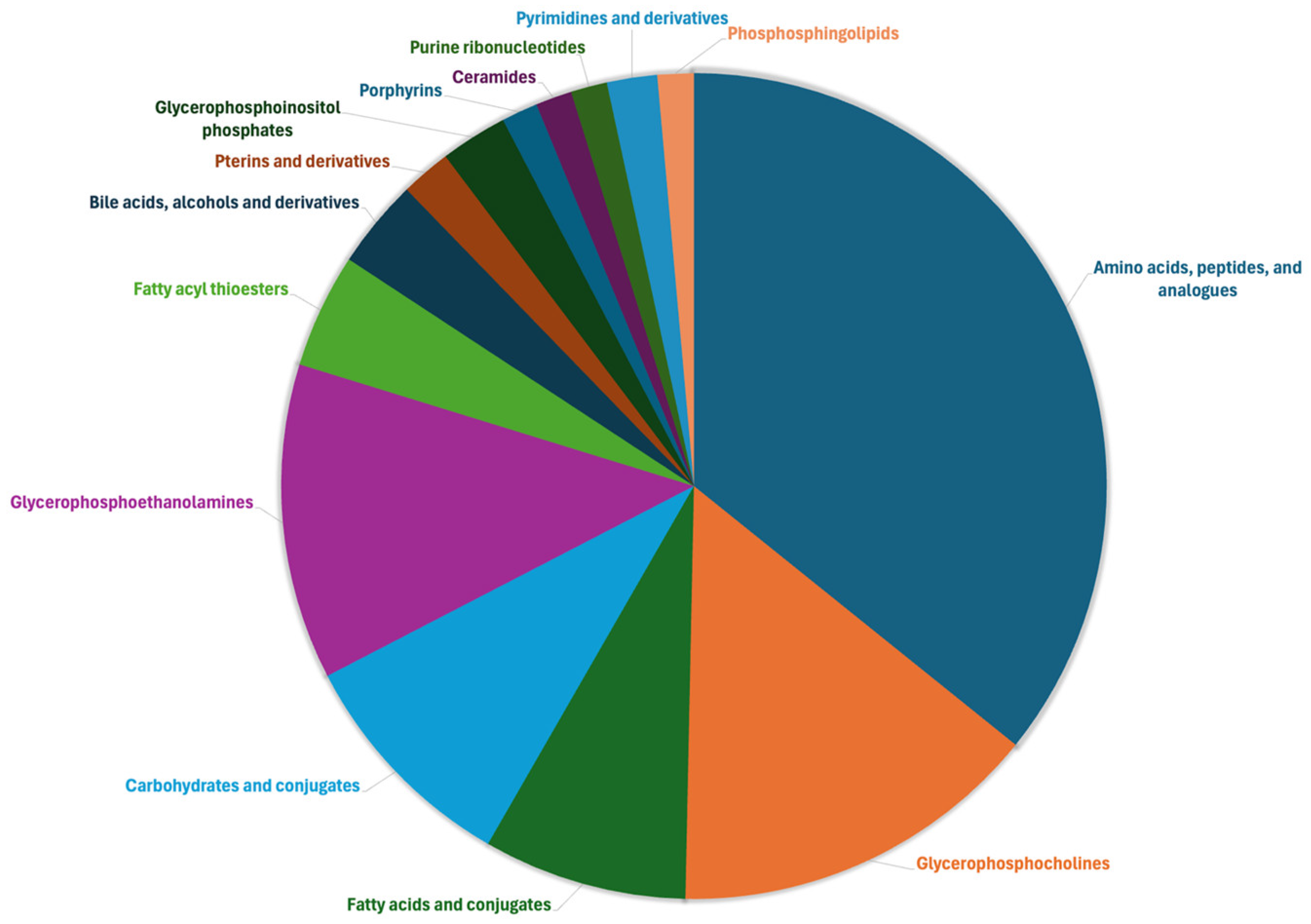

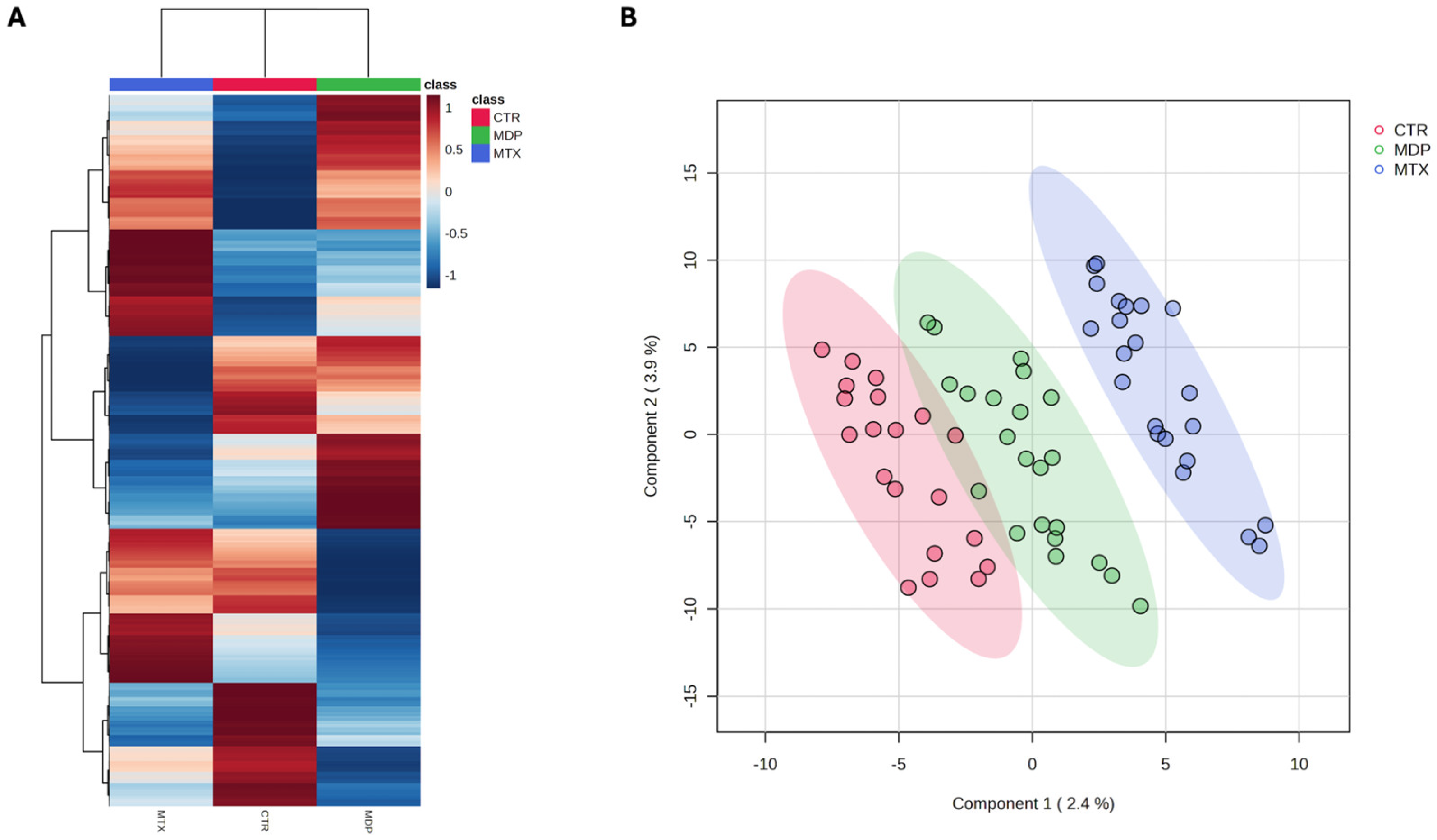

2.1. Plasma Metabolome and Multivariate Statistical Discrimination

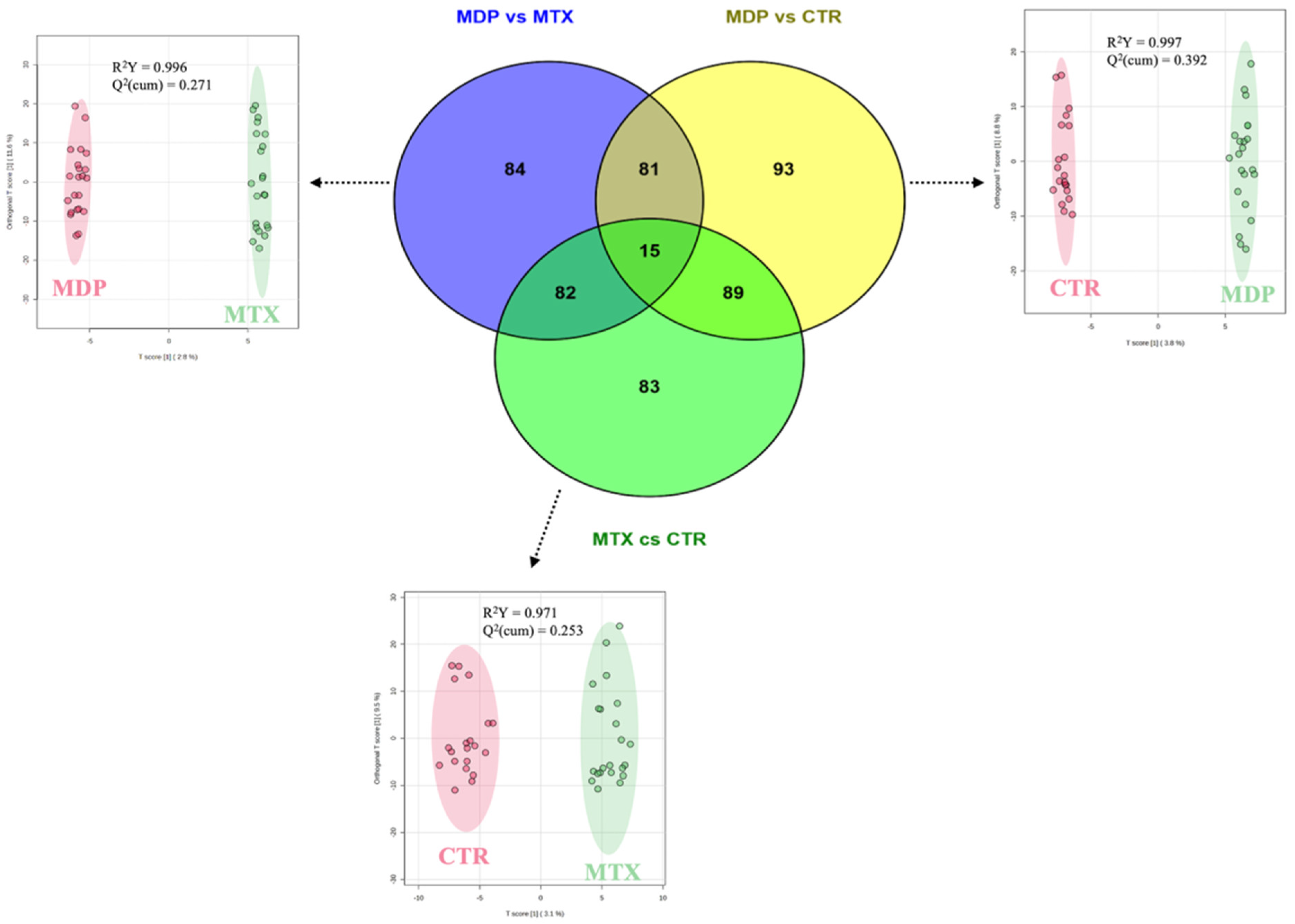

2.2. Pairwise Comparisons from OPLS-DA and Venn Diagram

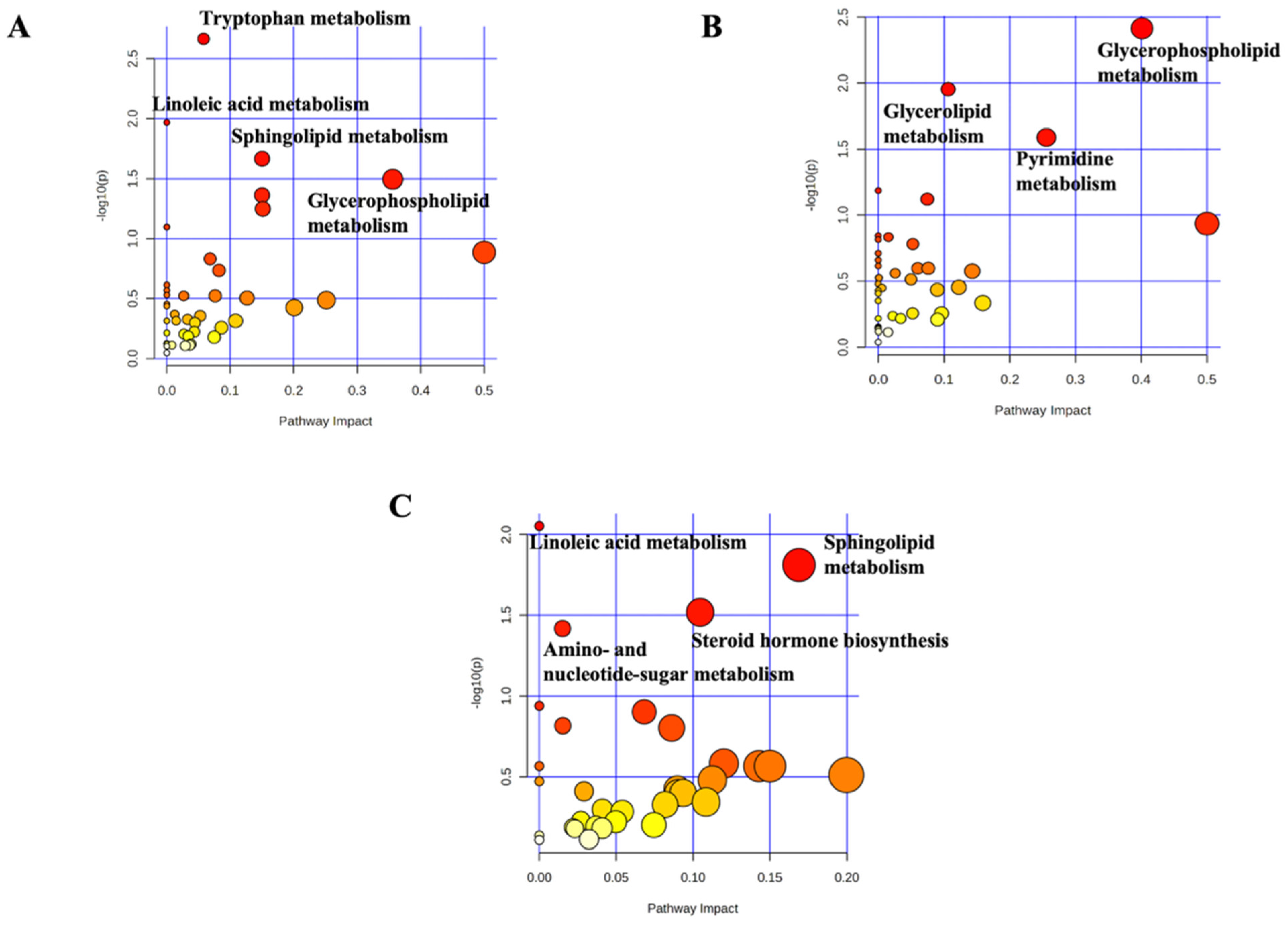

2.3. Pathway Analyses and Exclusive Biomarker Compounds of MDP

3. Discussion

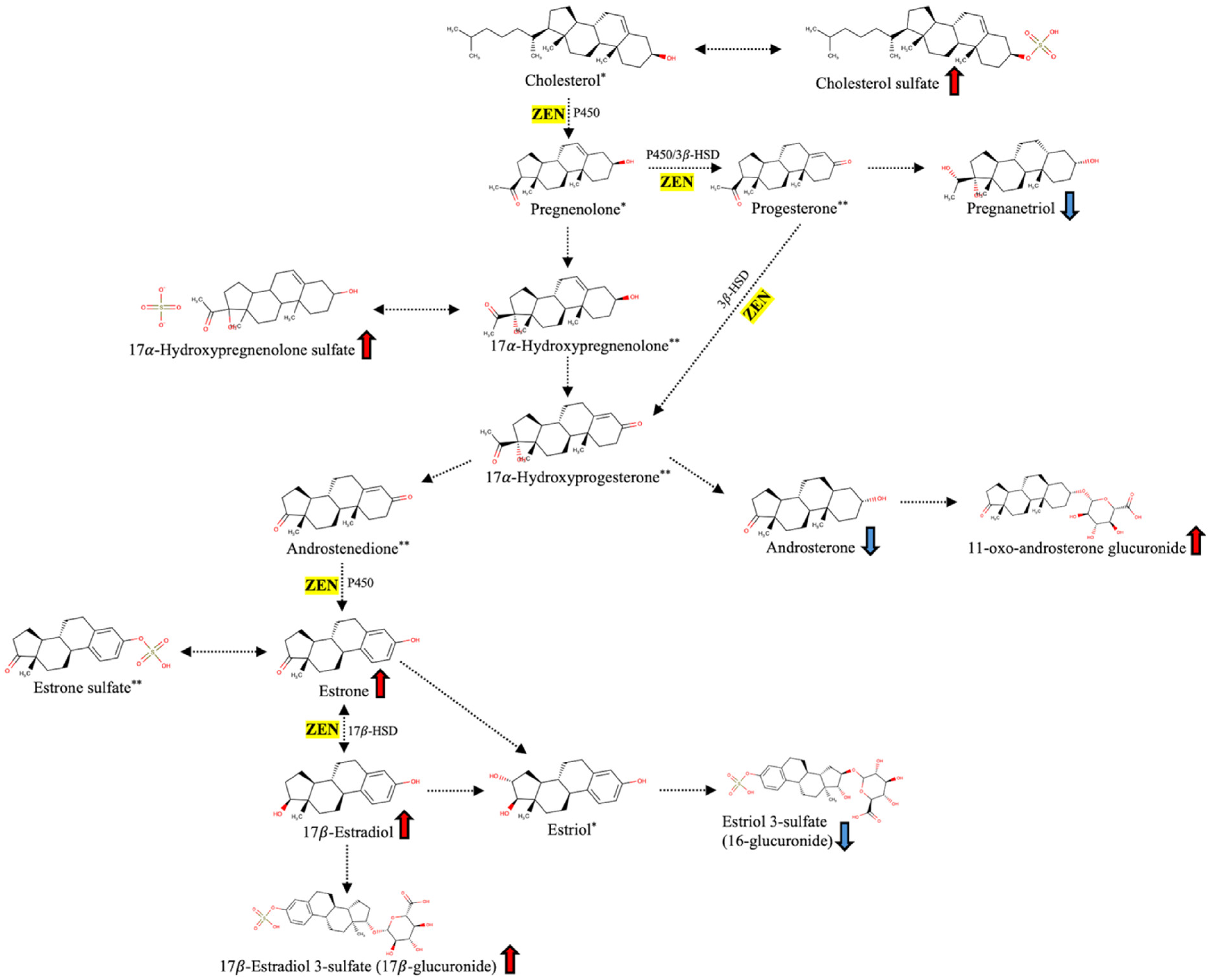

3.1. Metabolic Disruptions Caused by Fusarium Mycotoxins (MTX vs. CTR)

3.2. Protective Effects of the Mycotoxin-Deactivating Product (MDP vs. MTX)

3.3. Exploratory Metabolomic Differences Between MDP and CTR Groups

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Experimental Cows and Diets

5.2. Collection of Plasma Samples and Extraction of Metabolites

5.3. Untargeted Metabolomic Profiling Based on HRMS

5.4. Multivariate Statistics and Pathway Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- González-Jartín, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cañás, I.; Alvariño, R.; Alfonso, A.; Sainz, M.J.; Vieytes, M.R.; Gomes, A.; Ramos, I.; Botana, L.M. Occurrence of mycotoxins in total mixed ration of dairy farms in Portugal and carry-over to milk. Food Control 2024, 165, 110682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.; Lemos, A.; Silva, J.; Rodrigues, M.; Simões, J. Mycotoxins evaluation of total mixed ration (TMR) in bovine dairy farm: An update. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, A.; Mosconi, M.; Trevisi, E.; Santos, R.R. Adverse Effects of Fusarium Toxins in Ruminants: A Review of In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. Dairy 2022, 3, 474–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Effects of mycotoxin-contaminated feed on farm animals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 122087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, Z.C.; Averkieva, O.; Rajauria, G.; Pierce, K.M. The effect of feedborne Fusarium mycotoxins on dry matter intake, milk production and blood metabolites of early lactation dairy cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2019, 253, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Fancello, F.; Rocchetti, G. Mycotoxicoses. In Rumen Health Compendium, 2nd ed.; Tedeschi, L.O., Nagaraja, T.G., Eds.; Kendall Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2024; pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar, R.; Raghavendra, V.B.; Rachitha, P. A comprehensive review of mycotoxins, their toxicity, and innovative detoxification methods. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudergue, C.; Burel, C.; Dragacci, S.; Favrot, M.-C.; Fremy, J.-M.; Massimi, C.; Pringent, P.; Debongnie, P.; Pussemier, L.; Boudra, H.; et al. Review of mycotoxin-detoxifying agents used as feed additives: Mode of action, efficacy and feed/food safety (report). EFSA Support. Publ. 2009, 6, 22E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catellani, A.; Ghilardelli, F.; Trevisi, E.; Cecchinato, A.; Bisutti, V.; Fumagalli, F.; Swamy, H.V.L.N.; Han, Y.; van Kuijk, S.; Gallo, A. Effects of Supplementation of a Mycotoxin Mitigation Feed Additive in Lactating Dairy Cows Fed Fusarium Mycotoxin-Contaminated Diet for an Extended Period. Toxins 2023, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, M.H.; Daniel, J.B.; Sadri, H.; Schuchardt, S.; Martín-Tereso, J.; Sauerwein, H. Longitudinal characterization of the metabolome of dairy cows transitioning from one lactation to the next: Investigations in blood serum. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 1263–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Qin, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, W.; Aschalew, N.D.; et al. Impact of deoxynivalenol on rumen function, production, and health of dairy cows: Insights from metabolomics and microbiota analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Ghilardelli, F.; Bonini, P.; Lucini, L.; Masoero, F.; Gallo, A. Changes of Milk Metabolomic Profiles Resulting from a Mycotoxins-Contaminated Corn Silage Intake by Dairy Cows. Metabolites 2021, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, N.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.; Wang, J. The biochemical and metabolic profiles of dairy cows with mycotoxins-contaminated diets. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catellani, A.; Mossa, F.; Gabai, G.; D’Hallewin, J.S.K.; Trevisi, E.; Faas, J.; Artavia, I.; Labudova, S.; Piccioli-Cappelli, F.; Minuti, A.; et al. Efficacy of a mycotoxin deactivating product to reduce the impact of Fusarium mycotoxins contaminated ration in dairy cows during early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 9627–9650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, J.; Kersten, S.; Meyer, U.; Engelhardt, U.; Dänicke, S. Residues of zearalenone (ZEN), deoxynivalenol (DON) and their metabolites in plasma of dairy cows fed Fusarium contaminated maize and their relationships to performance parameters. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 65, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunade, I.; Jiang, I.; Adeyemi, J.; Oliveira, A.; Vyas, D.; Adesogan, A. Biomarker of aflatoxin ingestion: 1H NMR-based plasma metabolomics of dairy cows fed aflatoxin B1 with or without sequestering agents. Toxins 2018, 10, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, J.W.; Rico, J.E. Invited review: Sphingolipid biology in the dairy cow: The emerging role of ceramide. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 7619–7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.T.; Merrill, A.H. Ceramide synthase inhibition by fumonisins: A perfect storm of perturbed sphingolipid metabolism, signaling, and disease. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fang, Q.; Xie, T.; Gong, X. Mechanism of ceramide synthase inhibition by fumonisin B1. Structure 2024, 32, 1419–1428.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Szabó, A. Fumonisin distorts the cellular membrane lipid profile: A mechanistic insight. Toxicology 2024, 506, 153860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, P.; Lassallette, E.; Beaujardin-Daurian, U.; Travel, A. Fumonisins alone or mixed with other fusariotoxins increase the C22–24:C16 sphingolipid ratios in chicken livers, while deoxynivalenol and zearalenone have no effect. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 395, 111005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, D.K.; Sandrock, L.M.; Most, E.; Koch, C.; Ringseis, R.; Eder, K. Performance and metabolic, inflammatory, and oxidative stress-related parameters in early lactating dairy cows with high and low hepatic FGF21 expression. Animals 2023, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Anwar, F.; Ghazali, F.M. A comprehensive review of mycotoxins: Toxicology, detection, and effective mitigation approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jin, Y.; Wu, S.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, H.; Shen, J.; Zhou, C.; Fu, Y.; Li, R.; et al. Deoxynivalenol induces oxidative stress, inflammatory response and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M. Metabolism of zearalenone in farm animals. In Fusarium Mycotoxins, Taxonomy and Pathogenicity, 1st ed.; Chelkowsi, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, F.; Caloni, F.; Schreiber, N.B.; Cortinovis, C.; Spicer, L.J. In vitro effects of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone major metabolites alone and combined, on cell proliferation, steroid production and gene expression in bovine small-follicle granulosa cells. Toxicon 2016, 109, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangsuwan, T.; Haghdoost, S. The Nucleotide Pool, a Target for Low-Dose γ-Ray-Induced Oxidative Stress. Radiat. Res. 2008, 170, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yong, K.; Du, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Ma, L.; Yao, X.; Shen, L.; Yu, S.; Yan, Z.; et al. Association between Tryptophan Metabolism and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Dairy Cows with Ketosis. Metabolites 2023, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporta, J.; Moore, S.A.E.; Peters, M.W.; Peters, T.L.; Hernandez, L.L. Short communication: Circulating serotonin (5-HT) concentrations on day 1 of lactation as a potential predictor of transition-related disorders. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 5146–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, M.K.; Cheng, A.A.; Hernandez, L.L. Graduate Student Literature Review: Serotonin and calcium metabolism: A story unfolding. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 13008–13019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenkrug, G. Antioxidant effects of N-acetylserotonin: Possible mechanisms and clinical implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1053, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bionaz, M.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Busato, S. Advances in fatty acids nutrition in dairy cows: From gut to cells and effects on performance. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.Z.; Shen, L.H.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Y.X.; Bai, L.P.; Yu, S.M.; Yao, X.P.; Ren, Z.H.; Yang, Y.X.; Cao, S.Z. Plasma metabolite changes in dairy cows during parturition identified using untargeted metabolomics. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 4639–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Tan, Z.L.; Li, Z.C.; Gao, S.; Yi, K.L.; Zhou, C.S.; Tang, S.X.; Han, X.F. Metabolomic changes in the liver tissues of cows in early lactation supplemented with dietary rumen-protected glucose during the transition period. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 281, 115093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.J.C.; Fonseca, L.M.; Poletti, G.; Martins, N.P.; Grigoletto, N.T.S.; Chesini, R.G.; Tonin, F.G.; Cortinhas, C.S.; Acedo, T.S.; Artavia, I.; et al. Anti-mycotoxin feed additives: Effects on metabolism, mycotoxin excretion, performance, and total-tract digestibility of dairy cows fed artificially multi-mycotoxin-contaminated diets. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 108, 7891–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruhauf, S.; Pühringer, D.; Thamhesl, M.; Fajtl, P.; Kunz-Vekiru, E.; Höbartner-Gussl, A.; Schatzmayr, G.; Adam, G.; Damborsky, J.; Djinovic-Carugo, K.; et al. Bacterial lactonases ZenA with noncanonical structural features hydrolyze the mycotoxin zearalenone. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 3392–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartinger, D.; Moll, W. Fumonisin elimination and prospects for detoxification by enzymatic transformation. World Mycotoxin J. 2011, 4, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinl, S.; Hartinger, D.; Thamhesl, M.; Vekiru, E.; Krska, R.; Schatzmayr, G.; Moll, W.-D.; Grabherr, R. Degradation of fumonisin B1 by the consecutive action of two bacterial enzymes. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 145, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietri, A.; Bertuzzi, T. Simple phosphate buffer extraction for the determination of fumonisins in masa, maize, and derived products. Food Anal. Methods 2012, 5, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, T.; Camardo Leggieri, M.; Battilani, P.; Pietri, A. Co-occurrence of type A and B trichothecenes and zearalenone in wheat grown in northern Italy over the years 2009–2011. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill. 2014, 7, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Piccioli-Cappelli, F.; Zini, S.; Trevisi, E.; Minuti, A. Impact of dry-off and lyophilized Aloe arborescens supplementation on plasma metabolome of dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, A.; Fitzsimmons, C.; Mandal, R.; Piri-Moghadam, H.; Zheng, J.; Guo, A.; Li, C.; Guan, L.L.; Wishart, D.S. The Bovine Metabolome. Metabolites 2020, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazenović, I.; Kind, T.; Sa, M.R.; Ji, J.; Vaniya, A.; Wancewicz, B.; Roberts, B.S.; Torbašinović, H.; Lee, T.; Mehta, S.S.; et al. Structure annotation of all mass spectra in untargeted metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 2155–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; MacDonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W398–W406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discriminant Marker of MDP | MDP vs. MTX | MDP vs. CTR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log2 FC | AUC (ROC) | p-Value | Log2 FC | AUC (ROC) | p-Value | |

| N-Acetylhistidine | 0.36 | 0.77 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 2.4 × 10−3 |

| Aminomalonic acid | 0.46 | 0.77 | 2.2 × 10−3 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 1.6 × 10−3 |

| 8-Hydroxyadenine | 0.32 | 0.74 | 1.5 × 10−2 | 0.37 | 0.77 | 7.8 × 10−3 |

| Pipecolic acid | 0.30 | 0.71 | 1.1 × 10−2 | 0.34 | 0.74 | 5.5 × 10−3 |

| PC(20:1(11Z)/18:2(9Z,12Z)) | −0.59 | 0.77 | >0.05 | −0.57 | 0.75 | 4.1 × 10−2 |

| 2-(Formamido)-N1-(5-phospho-D-ribosyl)acetamidine | 0.45 | 0.72 | 7.9 × 10−3 | 0.49 | 0.74 | 5.3 × 10−3 |

| Allantoic acid | 0.46 | 0.74 | 6.2 × 10−3 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| Riboflavin | 0.73 | 0.77 | 2.9 × 10−3 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 1.5 × 10−2 |

| 4-(2-Amino-3-hydroxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxobutanoic acid | 0.38 | 0.71 | 2.4 × 10−2 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 4.1 × 10−2 |

| Metabolic Pathways | n° of VIP Compounds | Cumulative log2FC | Most Discriminant VIP Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDP vs. MTX | |||

| Tryptophan metabolism | 8 | 1.52 | 4,6-Dihydroxyquinoline (VIP score: 2.458; AUC: 0.74; p-value: 4.7 × 10−3) |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 7 | −1.31 | L-Serine (VIP score: 2.372; AUC: 0.72; p-value: 8.8 × 10−3) |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 38 | −17.46 | PE(22:2(13Z,16Z)/16:0) (VIP score: 2.221; AUC: 0.69; p-value: 1.3 × 10−2) |

| MDP vs. CTR | |||

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 39 | −24.47 | PE(14:1(9Z)/18:4(6Z,9Z,12Z,15Z)) (VIP score: 2.205; AUC: 0.66; p-value: 2.8 × 10−3) |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 4 | 0.89 | CDP (VIP score: 2.411; AUC: 0.77; p-value: 1.6 × 10−3) |

| MTX vs. CTR | |||

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 7 | 2.67 | Ceramide (t18:0/16:0) (VIP score: 1.686; AUC: 0.69; p-value: 3.6 × 10−2) |

| Steroid hormones biosynthesis | 12 | 0.27 | Pregnanetriol (VIP score: 2.171; AUC: 0.67; p-value: 2.2 × 10−2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rocchetti, G.; Catellani, A.; Lapris, M.; Reisinger, N.; Faas, J.; Artavia, I.; Labudova, S.; Trevisi, E.; Gallo, A. Plasma Metabolomics Reveals Systemic Metabolic Remodeling in Early-Lactation Dairy Cows Fed a Fusarium-Contaminated Diet and Supplemented with a Mycotoxin-Deactivating Product. Toxins 2026, 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010009

Rocchetti G, Catellani A, Lapris M, Reisinger N, Faas J, Artavia I, Labudova S, Trevisi E, Gallo A. Plasma Metabolomics Reveals Systemic Metabolic Remodeling in Early-Lactation Dairy Cows Fed a Fusarium-Contaminated Diet and Supplemented with a Mycotoxin-Deactivating Product. Toxins. 2026; 18(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocchetti, Gabriele, Alessandro Catellani, Marco Lapris, Nicole Reisinger, Johannes Faas, Ignacio Artavia, Silvia Labudova, Erminio Trevisi, and Antonio Gallo. 2026. "Plasma Metabolomics Reveals Systemic Metabolic Remodeling in Early-Lactation Dairy Cows Fed a Fusarium-Contaminated Diet and Supplemented with a Mycotoxin-Deactivating Product" Toxins 18, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010009

APA StyleRocchetti, G., Catellani, A., Lapris, M., Reisinger, N., Faas, J., Artavia, I., Labudova, S., Trevisi, E., & Gallo, A. (2026). Plasma Metabolomics Reveals Systemic Metabolic Remodeling in Early-Lactation Dairy Cows Fed a Fusarium-Contaminated Diet and Supplemented with a Mycotoxin-Deactivating Product. Toxins, 18(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010009