Efficient Expression of Lactone Hydrolase Cr2zen for Scalable Zearalenone Degradation in Pichia pastoris

Abstract

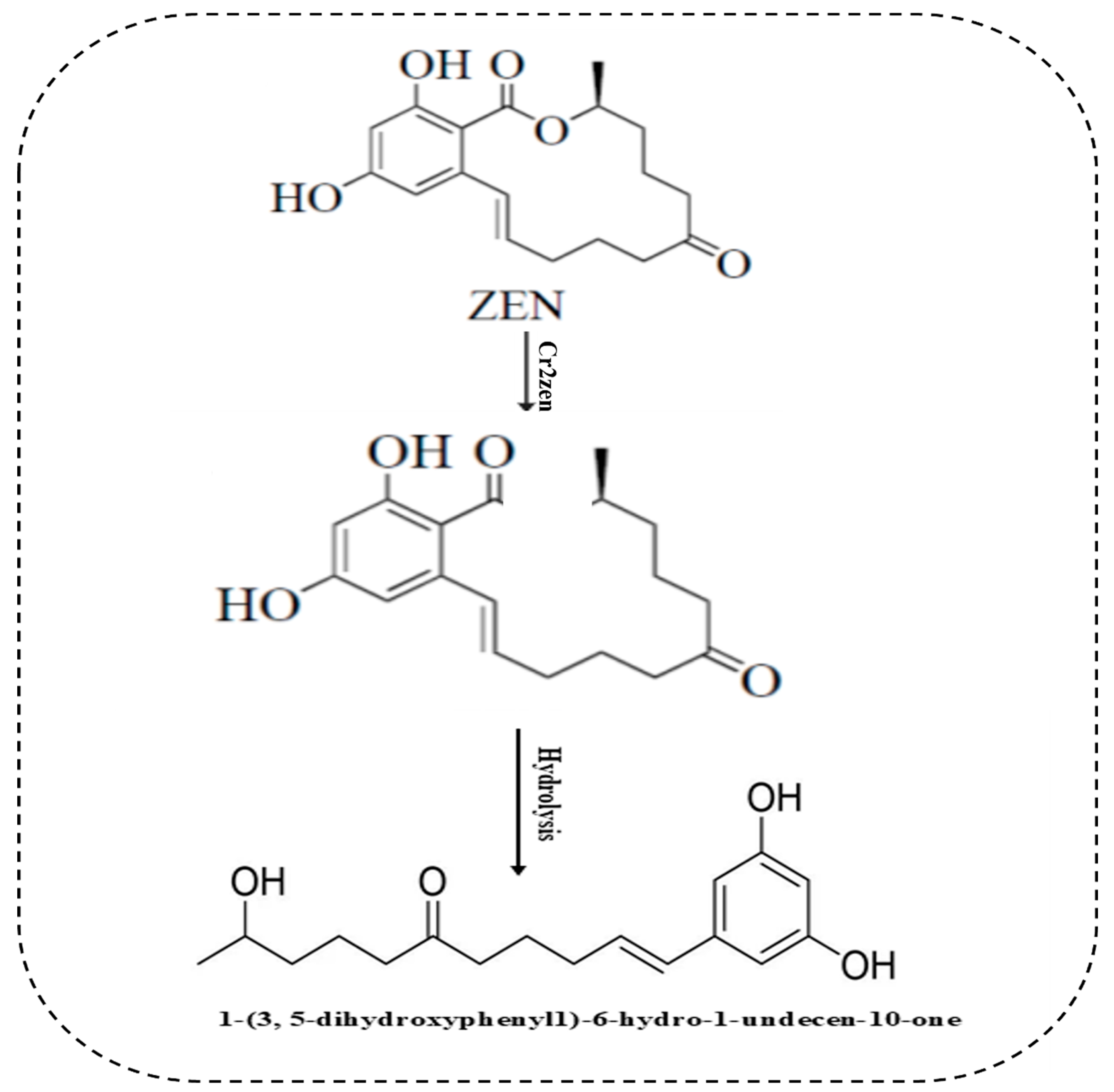

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Gene Cloning and Sequence Analysis

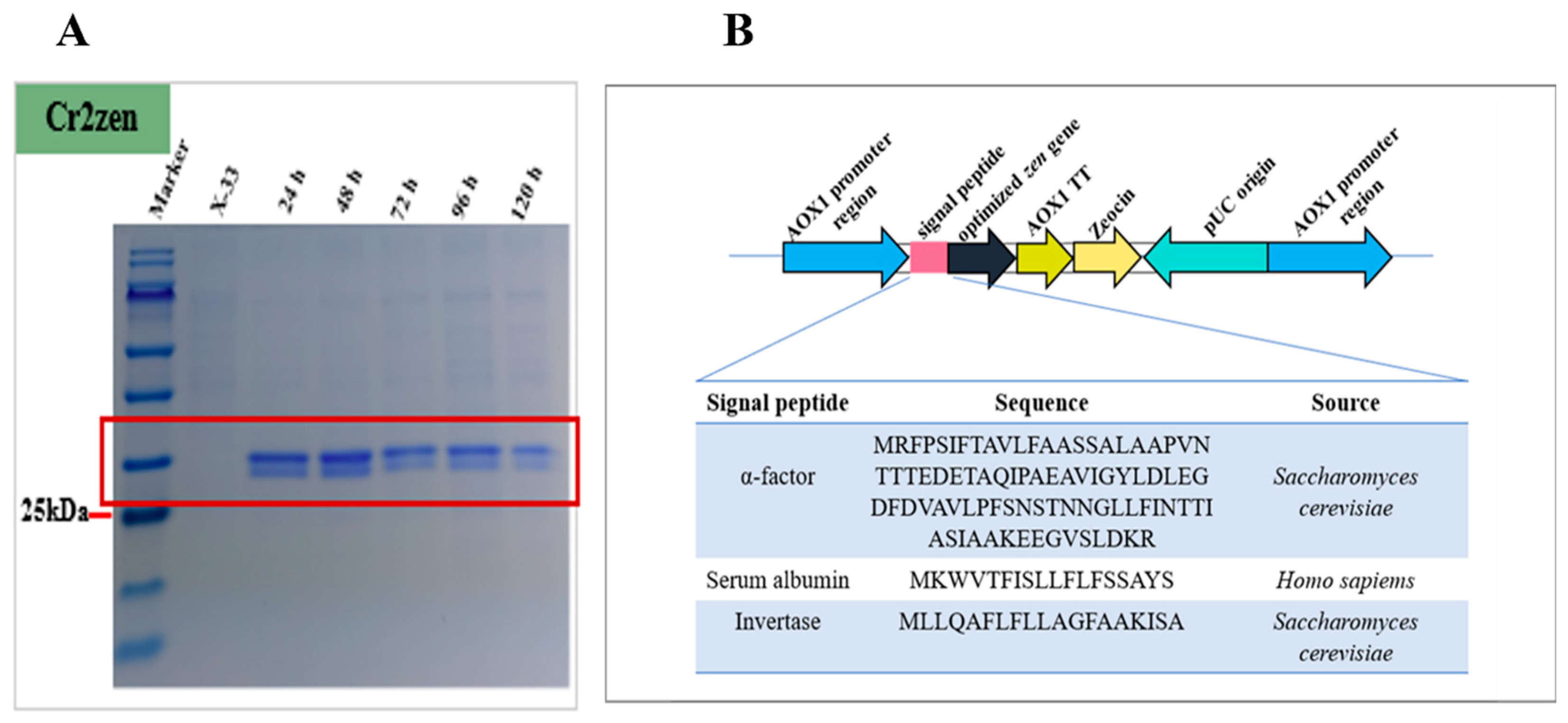

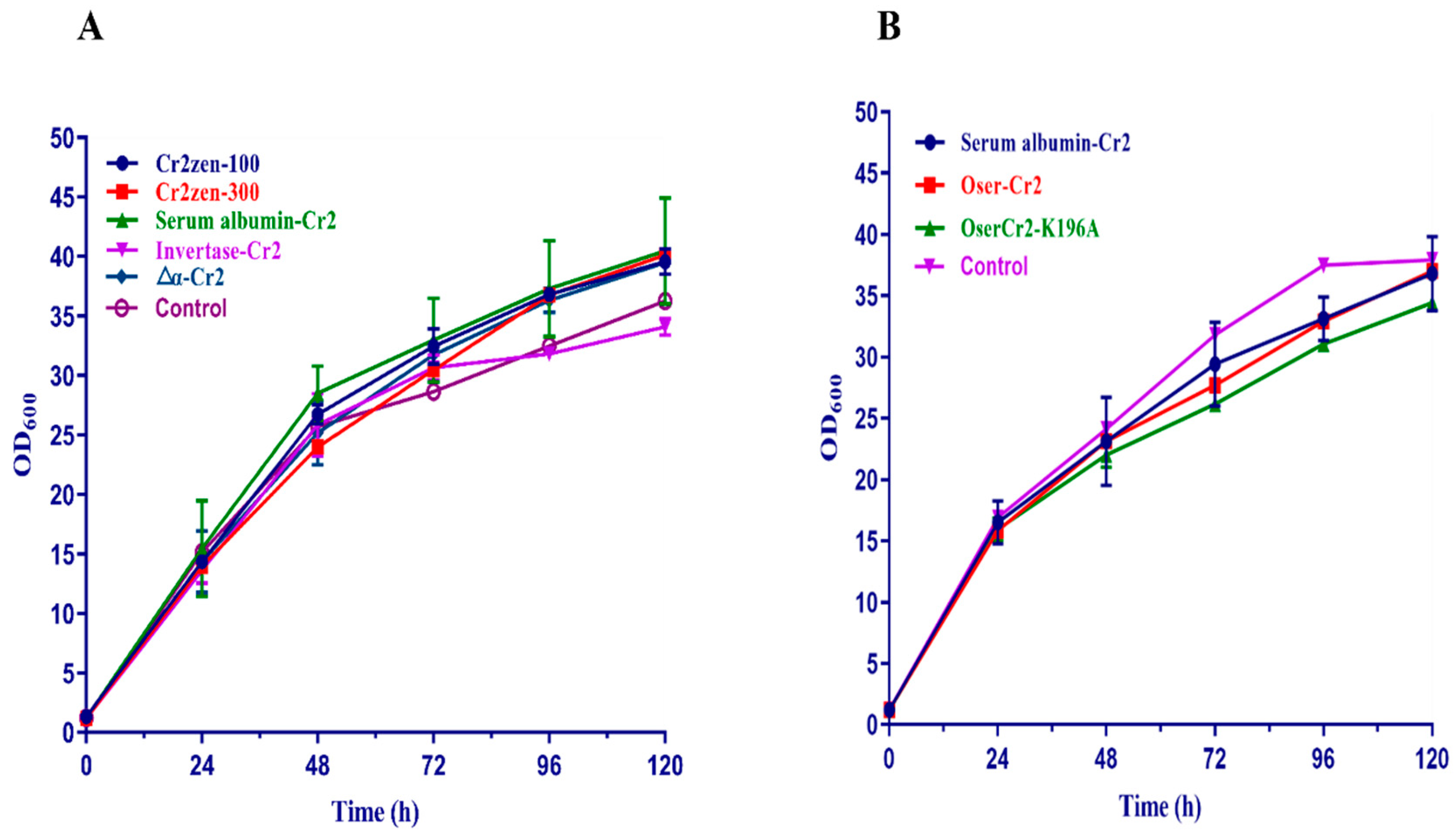

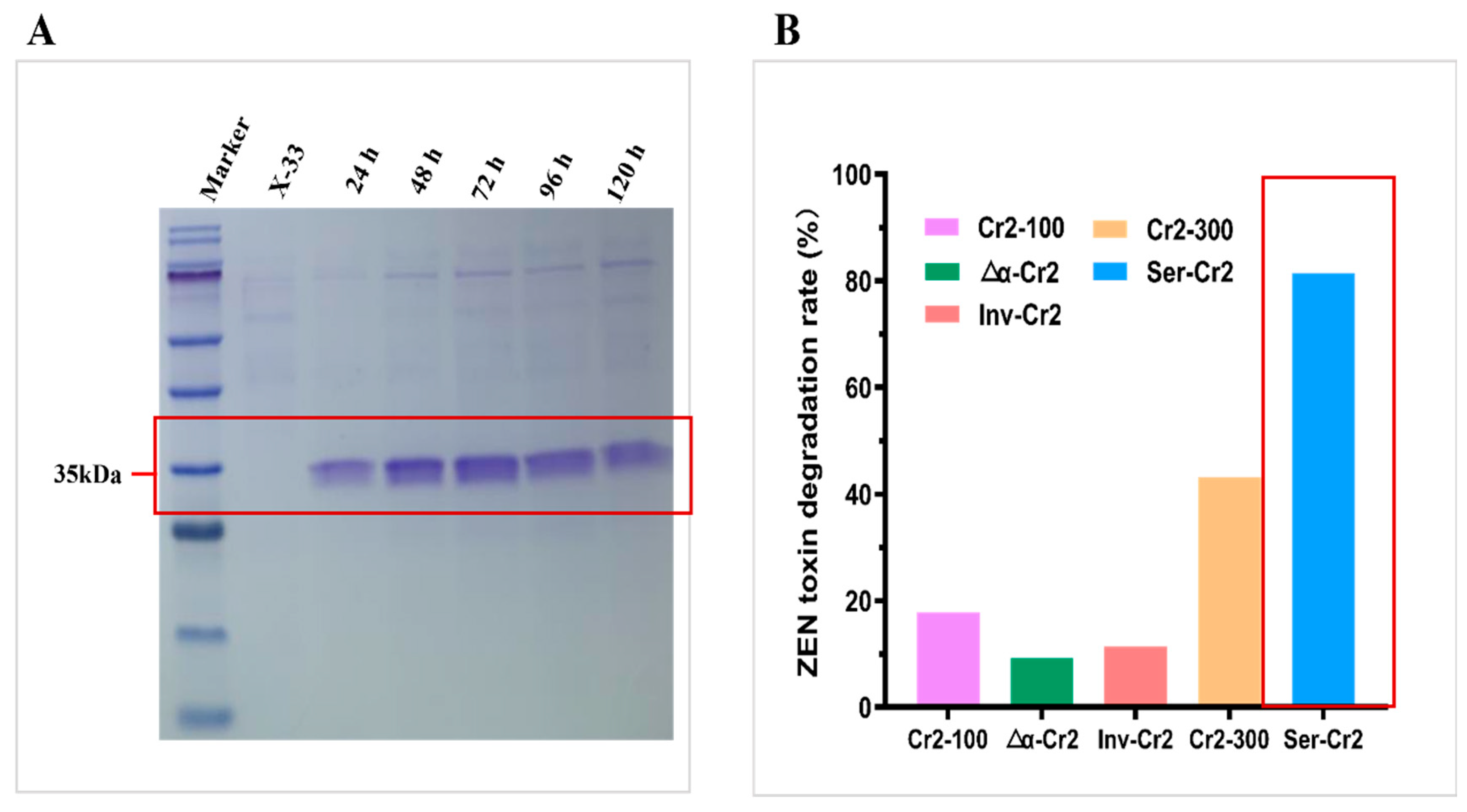

2.2. Signal Peptide Optimization of Cr2zen in P. pastoris

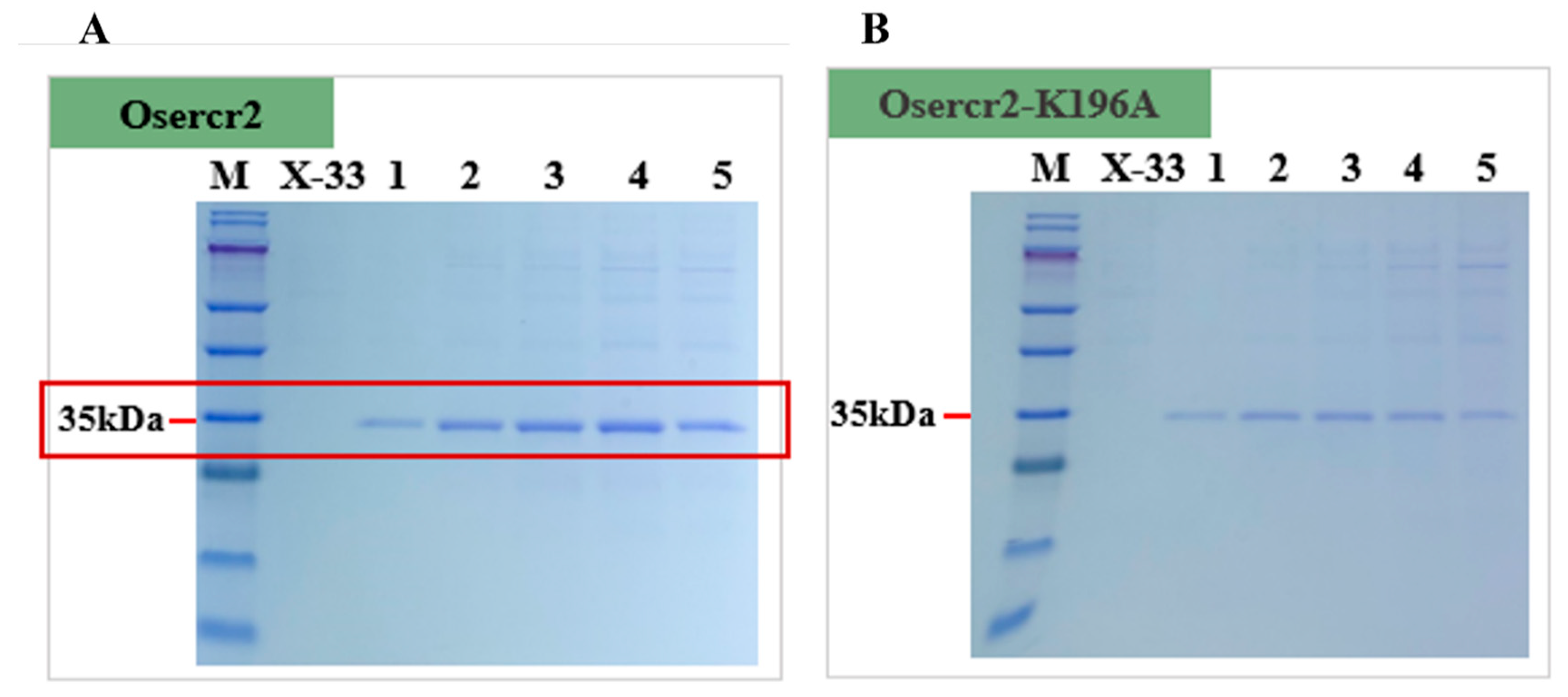

2.3. Enhanced Expression of Cr2zen in P. pastoris

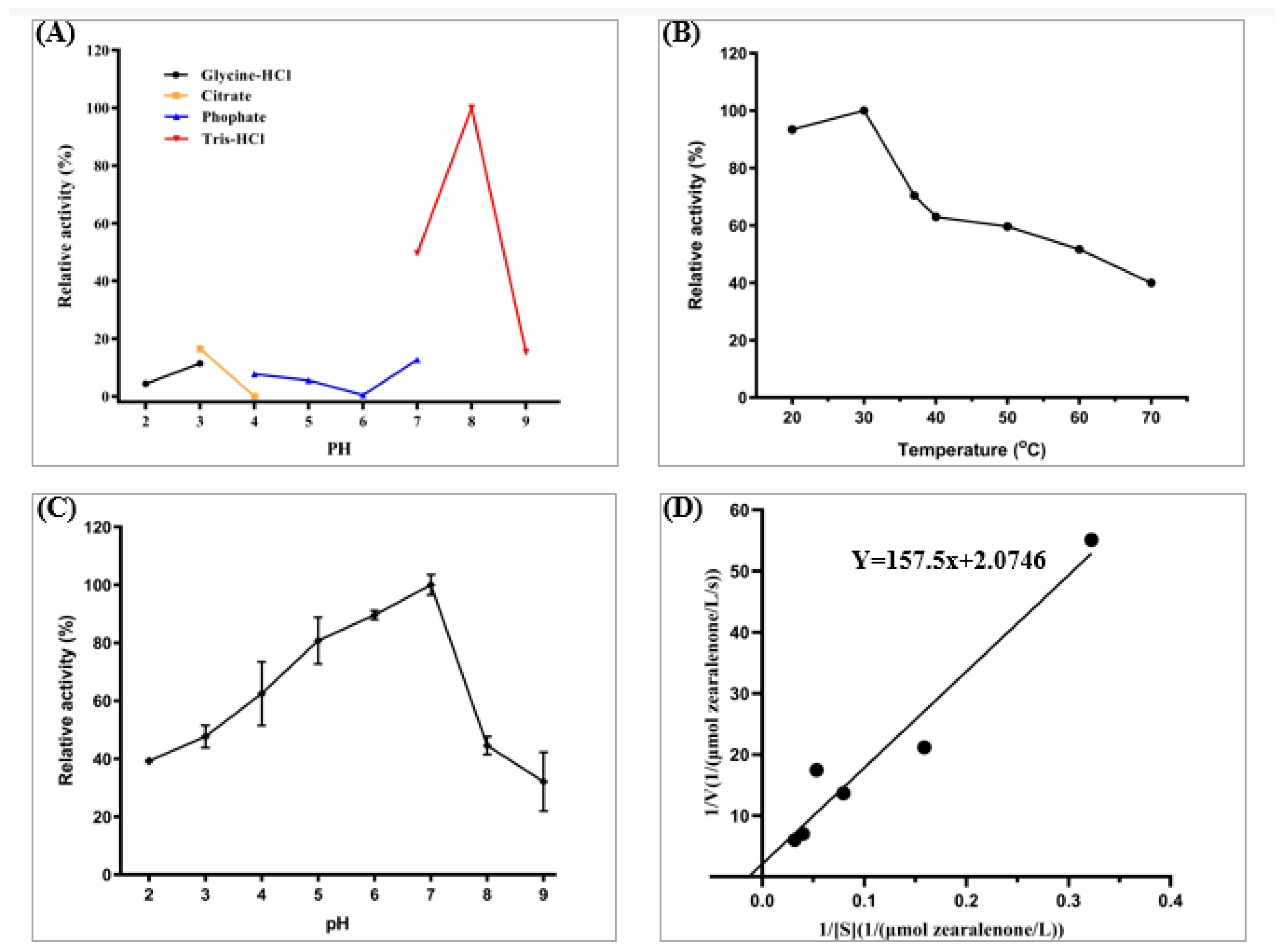

2.4. Enzymatic Characterization of Lactone Hydrolase Cr2zen

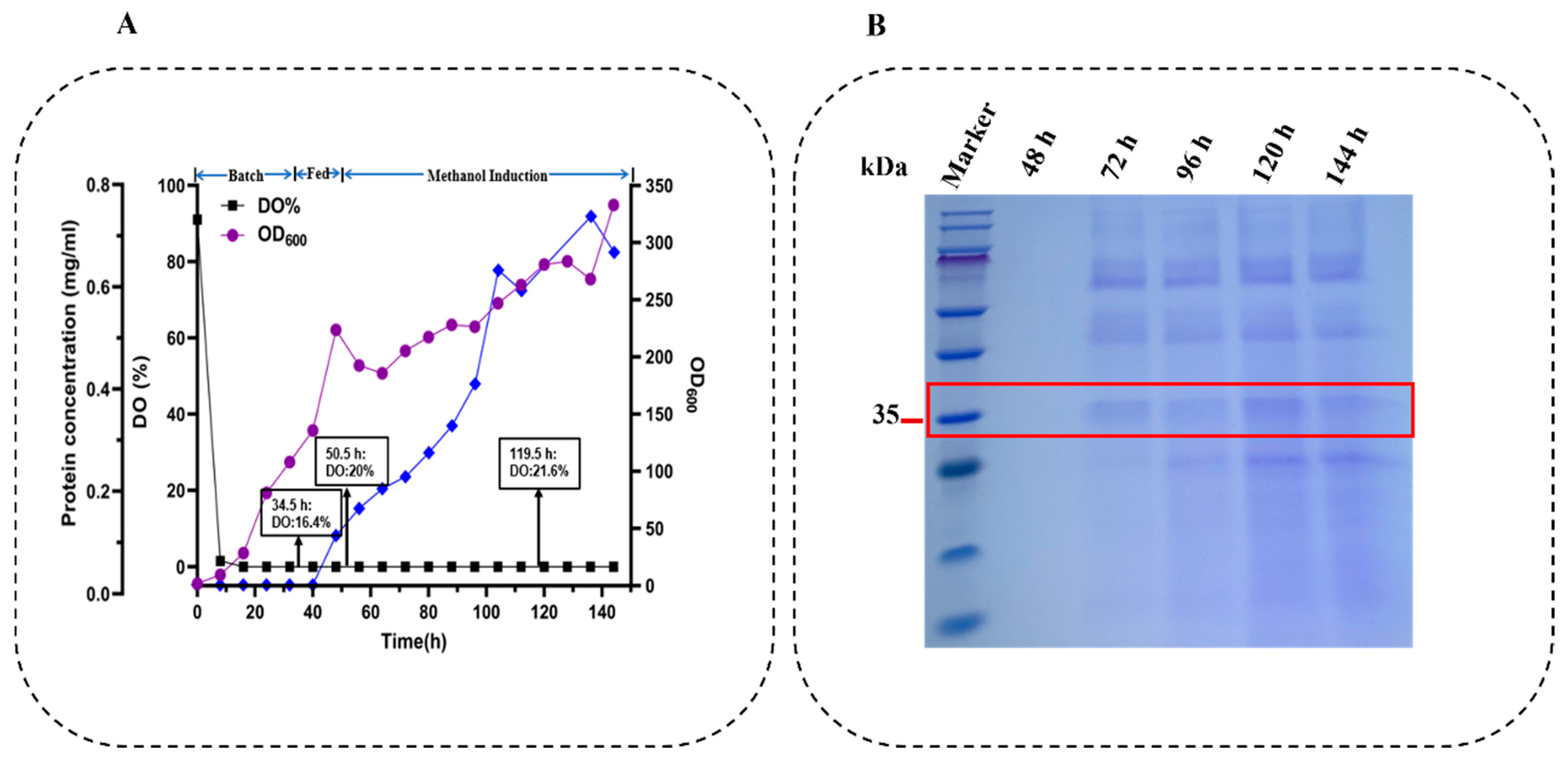

2.5. High-Density Fermentation of Strain Ser-Cr2

2.6. Codon-Optimized Oser-Cr2 for Enhanced Expression

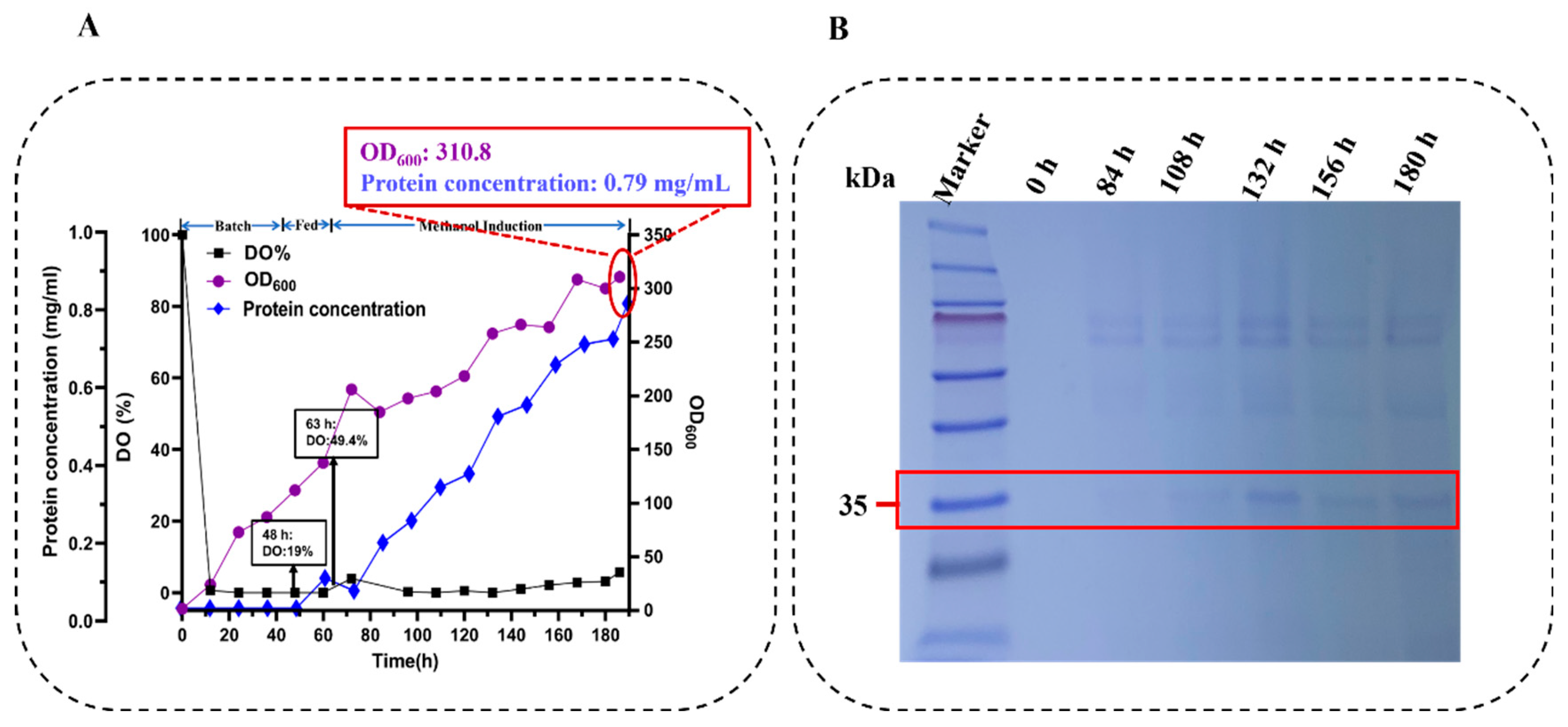

2.7. High-Density Fermentation of Oser-Cr2 in Pichia pastoris

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmids, Strains, Chemicals and Media

4.2. Gene Cloning and Expression

4.3. Enzyme Induction and Protein Analysis

4.4. Optimization of Cr2zen Production

4.5. Expression of Cr2zen with High-Density Fermentation

4.6. Zearalenone Degradation Assay

4.7. HPLC Analysis

4.8. Biochemical Characterization

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tu, Y.; Liu, S.; Cai, P.; Shan, T. Global distribution, toxicity to humans and animals, biodegradation, and nutritional mitigation of deoxynivalenol: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 3951–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in occurrence, importance, and mycotoxin control strategies: Prevention and detoxification in foods. Foods 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goda, A.A.; Shi, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, L.; Abdel-Galil, M.; Salem, S.H.; Ayad, E.G.; Deabes, M. Global health and economic impacts of mycotoxins: A comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, C.; Arredondo, C.; Echeverría-Vega, A.; Gordillo-Fuenzalida, F. Penicillium spp. mycotoxins found in food and feed and their health effects. World Mycotoxin J. 2020, 13, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navale, V.; Vamkudoth, K.R.; Ajmera, S.; Dhuri, V. Aspergillus derived mycotoxins in food and the environment: Prevalence, detection, and toxicity. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1008–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrivá, L.; Font, G.; Manyes, L.; Berrada, H. Studies on the presence of mycotoxins in biological samples: An overview. Toxins 2017, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.B.; Patriarca, A.; Magan, N. Alternaria in food: Ecophysiology, mycotoxin production and toxicology. Mycobiology 2015, 43, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huangfu, B.; Xu, T.; Xu, W.; Asakiya, C.; Huang, K.; He, X. Research progress of safety of zearalenone: A review. Toxins 2022, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boevre, M.; Jacxsens, L.; Lachat, C.; Eeckhout, M.; Di Mavungu, J.D.; Audenaert, K.; Maene, P.; Haesaert, G.; Kolsteren, P.; De Meulenaer, B. Human exposure to mycotoxins and their masked forms through cereal-based foods in Belgium. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 218, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoui, A.; El Khoury, A.; Kallassy, M.; Lebrihi, A. Quantification of Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium culmorum by real-time PCR system and zearalenone assessment in maize. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 154, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheur, F.B.; Kouidhi, B.; Al Qurashi, Y.M.A.; Salah-Abbès, J.B.; Chaieb, K. Biotechnology of mycotoxins detoxification using microorganisms and enzymes. Toxicon 2019, 160, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, B.; Li, X.; Dong, L.; Javed, M.T.; Xu, L.; Saleemi, M.K.; Li, G.; Jin, B.; Cui, H.; Ali, A. Microbial and enzymatic battle with food contaminant zearalenone (ZEN). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 4353–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Identification of a potent enzyme for the detoxification of zearalenone. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 68, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Ren, C.; Gong, Y.; Gao, X.; Rajput, S.A.; Qi, D.; Wang, S. The insensitive mechanism of poultry to zearalenone: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.-Q.; Zhao, A.-H.; Wang, J.-J.; Tian, Y.; Yan, Z.-H.; Dri, M.; Shen, W.; De Felici, M.; Li, L. Oxidative stress as a plausible mechanism for zearalenone to induce genome toxicity. Gene 2022, 829, 146511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Liu, C.; Zheng, J.; Dong, Z.; Guo, N. Toxicity of zearalenone and its nutritional intervention by natural products. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10374–10400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balló, A.; Busznyákné Székvári, K.; Czétány, P.; Márk, L.; Török, A.; Szántó, Á.; Máté, G. Estrogenic and non-estrogenic disruptor effect of zearalenone on male reproduction: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Sagandykova, G.; Buszewski, B. Zearalenone and its metabolites: Effect on human health, metabolism and neutralisation methods. Toxicon 2019, 162, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Xu, H.; Ji, Q.; Xu, R.; Zhu, M.; Dang, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Y. Mutation, food-grade expression, and characterization of a lactonase for zearalenone degradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5107–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Gu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, W.; Wu, S.; Wang, H. Analysis of the roles of the ISLR2 gene in regulating the toxicity of zearalenone exposure in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Toxins 2022, 14, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, S.; De Saeger, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, F. Deglucosylation of zearalenone-14-glucoside in animals and human liver leads to underestimation of exposure to zearalenone in humans. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 2779–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgaru, C.V.; Marin, D.E.; Pistol, G.C.; Taranu, I. Zearalenone and the immune response. Toxins 2021, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, X.; Hai, J.; Si, X.; Li, J.; Fu, H.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. Roles of stress response-related signaling and its contribution to the toxicity of zearalenone in mammals. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3326–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wang, G.; Hou, M.; Du, S.; Han, J.; Yu, Y.; Gao, H.; He, D.; Shi, J.; Lee, Y.-W. New hydrolase from Aeromicrobium sp. HA for the biodegradation of zearalenone: Identification, mechanism, and application. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2023, 71, 2411–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basit, A.; Liu, J.; Rahim, K.; Jiang, W.; Lou, H. Thermophilic xylanases: From bench to bottle. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, L.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y. High-level expression of a ZEN-detoxifying gene by codon optimization and biobrick in Pichia pastoris. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 193, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Ou, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Huang, H. Recent advances in detoxification strategies for zearalenone contamination in food and feed. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 30, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, M.A.; Scorer, C.A.; Clare, J.J. Foreign gene expression in yeast: A review. Yeast 1992, 8, 423–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Walczak, J.; Railean-Plugaru, V.; Rudnicka, J.; Buszewski, B. Investigation of zearalenone adsorption and biotransformation by microorganisms cultured under cellular stress conditions. Toxins 2019, 11, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, K.; Saladino, F.; Fernández-Blanco, C.; Ruiz, M.; Mañes, J.; Fernández-Franzón, M.; Meca, G.; Luciano, F. Reaction of zearalenone and α-zearalenol with allyl isothiocyanate, characterization of reaction products, their bioaccessibility and bioavailability in vitro. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-G.; Wang, Y.-D.; Huang, W.-F.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.-W. Molecular reaction mechanism for elimination of zearalenone during simulated alkali neutralization process of corn oil. Food Chem. 2020, 307, 125546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Zhou, H.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Ma, L. Effect of temperature and pH on the conversion between free and hidden zearalenone in zein. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 130001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi-Ando, N.; Kimura, M.; Kakeya, H.; Osada, H.; Yamaguchi, I. A novel lactonohydrolase responsible for the detoxification of zearalenone: Enzyme purification and gene cloning. Biochem. J. 2002, 365, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yin, L.; Hu, H.; Selvaraj, J.N.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G. Expression, functional analysis and mutation of a novel neutral zearalenone-degrading enzyme. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Engineering strategies for enhanced production of protein and bio-products in Pichia pastoris: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, R.; Hu, X.; Liu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, R.-T.; Jin, J.; Chen, C.-C. Characterization and crystal structure of a novel zearalenone hydrolase from Cladophialophora bantiana. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2017, 73, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi-Ando, N.; Ohsato, S.; Shibata, T.; Hamamoto, H.; Yamaguchi, I.; Kimura, M. Metabolism of zearalenone by genetically modified organisms expressing the detoxification gene from Clonostachys rosea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 3239–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H. Cloning and characterization of three novel enzymes responsible for the detoxification of zearalenone. Toxins 2022, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, D.K.; Devi, S.; Pandhi, S.; Sharma, B.; Maurya, K.K.; Mishra, S.; Dhawan, K.; Selvakumar, R.; Kamle, M.; Mishra, A.K. Occurrence, impact on agriculture, human health, and management strategies of zearalenone in food and feed: A review. Toxins 2021, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.L.; Chang, X.J.; Wang, N.X.; Sun, J.; Sun, C.P. Cloning of ZEN-degrading enzyme ZHD795 and study on degradation activity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, W.; Guang, C.; Mu, W. Zearalenone lactonase: Characteristics, modification, and application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 6877–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Shi, W.; Luo, J.; Peng, F.; Wan, C.; Wei, H. Cloning of zearalenone-degraded enzyme gene (ZEN-jjm) and its expression and activity analysis. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2010, 18, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Lu, D.; Xing, M.; Xu, Q.; Xue, F. Excavation, expression, and functional analysis of a novel zearalenone-degrading enzyme. Folia Microbiol. 2022, 67, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekiru, E.; Fruhauf, S.; Hametner, C.; Schatzmayr, G.; Krska, R.; Moll, W.; Schuhmacher, R. Isolation and characterisation of enzymatic zearalenone hydrolysis reaction products. World Mycotoxin J. 2016, 9, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Hirz, M.; Pichler, H.; Schwab, H. Protein expression in Pichia pastoris: Recent achievements and perspectives for heterologous protein production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 5301–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C. Zearalenone removal from corn oil by an enzymatic strategy. Toxins 2020, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looser, V.; Bruhlmann, B.; Bumbak, F.; Stenger, C.; Costa, M.; Camattari, A.; Fotiadis, D.; Kovar, K. Cultivation strategies to enhance productivity of Pichia pastoris: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Malaphan, W.; Xing, F.; Yu, B. Biodetoxification of fungal mycotoxins zearalenone by engineered probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus reuteri with surface-displayed lactonohydrolase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 8813–8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, K.; Han, Y.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, M. Codon usage bias regulates gene expression and protein conformation in yeast expression system P. pastoris. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Dang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, L.; Yu, C.-h.; Fu, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y. Codon usage is an important determinant of gene expression levels largely through its effects on transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E6117–E6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villada, J.C.; Brustolini, O.J.B.; Batista da Silveira, W. Integrated analysis of individual codon contribution to protein biosynthesis reveals a new approach to improving the basis of rational gene design. DNA Res. 2017, 24, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkaš, M.; Grujicic, N.; Geier, M.; Glieder, A.; Emmerstorfer-Augustin, A. The MFα signal sequence in yeast-based protein secretion: Challenges and innovations’. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Ouyang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, W.; Mu, W. Recent developments of mycotoxin-degrading enzymes: Identification, preparation and application. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 10089–10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juturu, V.; Wu, J.C. Heterologous protein expression in Pichia pastoris: Latest research progress and applications. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, K.R.; Dalvie, N.C.; Love, J.C. The yeast stands alone: The future of protein biologic production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 53, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, D.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Du, G.; Chen, J. High-level expression, purification, and enzymatic characterization of truncated poly (vinyl alcohol) dehydrogenase in methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales-Vallverdú, A.; Gasset, A.; Requena-Moreno, G.; Valero, F.; Montesinos-Seguí, J.L.; Garcia-Ortega, X. Synergic kinetic and physiological control to improve the efficiency of Komagataella phaffii recombinant protein production bioprocesses. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.J.; Pagazartaundua, A.; Glick, B.S.; Valero, F.; Ferrer, P. Bioreactor-scale cell performance and protein production can be substantially increased by using a secretion signal that drives co-translational translocation in Pichia pastoris. New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Khare, S.K. Advances in Microbial Alkaline Proteases: Addressing Industrial Bottlenecks Through Genetic and Enzyme Engineering. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 4861–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Ishigami, M.; Hashiba, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Terai, G.; Hasunuma, T.; Ishii, J.; Kondo, A. Avoiding entry into intracellular protein degradation pathways by signal mutations increases protein secretion in Pichia pastoris. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 2364–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, K.; Liu, P. Effect of Fold-Promoting Mutation and Signal Peptide Screening on Recombinant Glucan 1, 4-Alpha-maltohydrolase Secretion in Pichia pastoris. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 2579–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, G.; Ding, L.; Wei, D.; Zhou, H.; Chu, J.; Zhang, S.; Qian, J. Screening endogenous signal peptides and protein folding factors to promote the secretory expression of heterologous proteins in Pichia pastoris. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 306, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aza, P.; Molpeceres, G.; de Salas, F.; Camarero, S. Design of an improved universal signal peptide based on the α-factor mating secretion signal for enzyme production in yeast. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3691–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helian, Y.; Gai, Y.; Fang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D. A multistrategy approach for improving the expression of E. coli phytase in Pichia pastoris. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Off. J. Soc. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 47, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gong, G.; Pan, J.; Han, S.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Xie, L. High level expression and purification of recombinant human serum albumin in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2018, 147, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Qi, H. Engineering strategies for enhanced heterologous protein production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püllmann, P.; Knorrscheidt, A.; Münch, J.; Palme, P.R.; Hoehenwarter, W.; Marillonnet, S.; Alcalde, M.; Westermann, B.; Weissenborn, M.J. A modular two yeast species secretion system for the production and preparative application of unspecific peroxygenases. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, L.; Fang, H. Current advances of Pichia pastoris as cell factories for production of recombinant proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1059777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Li, W.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D. Effect and mechanism of signal peptide and maltose on recombinant type III collagen production in Pichia pastoris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 4369–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Lu, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y. The α-mating factor secretion signals and endogenous signal peptides for recombinant protein secretion in Komagataella phaffii. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tu, T.; Luo, H.; Huang, H.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Yao, B. Biochemical characterization and mutational analysis of a lactone hydrolase from Phialophora americana. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 68, 2570–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W. Degradation mechanism for Zearalenone ring-cleavage by Zearalenone hydrolase RmZHD: A QM/MM study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 135897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber-Dorninger, C.; Faas, J.; Doupovec, B.; Aleschko, M.; Stoiber, C.; Höbartner-Gußl, A.; Schöndorfer, K.; Killinger, M.; Zebeli, Q.; Schatzmayr, D. Metabolism of zearalenone in the rumen of dairy cows with and without application of a zearalenone-degrading enzyme. Toxins 2021, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidijala, L.; Uthoff, S.; van Kampen, S.J.; Steinbüchel, A.; Verhaert, R.M. Presence of protein production enhancers results in significantly higher methanol-induced protein production in Pichia pastoris. Microb. Cell Factories 2018, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Hsiung, H.-A.; Hong, K.-L.; Huang, C.-T. Enhancing the efficiency of the Pichia pastoris AOX1 promoter via the synthetic positive feedback circuit of transcription factor Mxr1. BMC Biotechnol. 2018, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño López, J.; Duran, L.; Avalos, J.L. Physiological limitations and opportunities in microbial metabolic engineering. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pan, L.; Liu, S.; Pan, L.; Li, X.; Wang, B. Recombinant expression and surface display of a zearalenone lactonohydrolase from Trichoderma aggressivum in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2021, 187, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-C.; Inwood, S.; Gong, T.; Sharma, A.; Yu, L.-Y.; Zhu, P. Fed-batch high-cell-density fermentation strategies for Pichia pastoris growth and production. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manstein, F.; Ullmann, K.; Kropp, C.; Halloin, C.; Triebert, W.; Franke, A.; Farr, C.-M.; Sahabian, A.; Haase, A.; Breitkreuz, Y. High density bioprocessing of human pluripotent stem cells by metabolic control and in silico modeling. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 1063–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; He, X.; Weng, P.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z. A review of yeast: High cell-density culture, molecular mechanisms of stress response and tolerance during fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2022, 22, foac050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschmanová, H.; Weninger, A.; Knejzlík, Z.; Melzoch, K.; Kovar, K. Engineering of the unfolded protein response pathway in Pichia pastoris: Enhancing production of secreted recombinant proteins. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 4397–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baets, J.; De Paepe, B.; De Mey, M. Delaying production with prokaryotic inducible expression systems. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, C.; Liu, H. Enhanced recombinant protein production under special environmental stress. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 630814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Cui, R.; Xu, Q.; Lan, D.; Wang, Y. Controlling specific growth rate for recombinant protein production by Pichia pastoris under oxidation stress in fed-batch fermentation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 6179–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez-Suberbie, M.L.; Morris, S.A.; Kaur, K.; Hickey, J.M.; Joshi, S.B.; Volkin, D.B.; Bracewell, D.G.; Mukhopadhyay, T.K. Holistic process development to mitigate proteolysis of a subunit rotavirus vaccine candidate produced in Pichia pastoris by means of an acid pH pulse during fed-batch fermentation. Biotechnol. Progr. 2020, 36, e2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, E.; El Banna, N.; Baïlle, D.; Heneman-Masurel, A.; Truchet, S.; Rezaei, H.; Huang, M.-E.; Béringue, V.; Martin, D.; Vernis, L. Causative links between protein aggregation and oxidative stress: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, W.; Yu, C.; Xia, J. Transcriptional downregulation of methanol metabolism key genes during yeast death in engineered Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, e202400328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, R.; Cui, L.; Jiang, T.; Shi, J.; Lu, C.; Li, P.; Zhou, M. Alter codon bias of the P. pastoris genome to overcome a bottleneck in codon optimization strategy development and improve protein expression. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 282, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camellato, B.R.; Brosh, R.; Ashe, H.J.; Maurano, M.T.; Boeke, J.D. Synthetic reversed sequences reveal default genomic states. Nature 2024, 628, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, E.; Sonderegger, L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Segessemann, T.; Künzler, M. Structural and functional analysis of peptides derived from KEX2-processed repeat proteins in agaricomycetes using reverse genetics and peptidomics. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02021–e02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhai, X.; Zhu, S.; Qu, Z.; Yuan, W.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C. Coexpression of Kex2 endoproteinase and Hac1 transcription factor to improve the secretory expression of bovine lactoferrin in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2019, 24, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gong, J.-S.; Su, C.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Rao, Z.-M.; Xu, Z.-H.; Shi, J.-S. Pathway engineering facilitates efficient protein expression in Pichia pastoris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 5893–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.-f.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Lin, Y.; Han, S. Comparative transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal the methanol dissimilation pathway of Pichia pastoris. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Verderame, T.D.; Leighton, J.M.; Sampey, B.P.; Appelbaum, E.R.; Patel, P.S.; Aon, J.C. Exometabolome analysis reveals hypoxia at the up-scaling of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae high-cell density fed-batch biopharmaceutical process. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergün, B.G.; Laçın, K.; Çaloğlu, B.; Binay, B. Second generation Pichia pastoris strain and bioprocess designs. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miserez, A.; Yu, J.; Mohammadi, P. Protein-based biological materials: Molecular design and artificial production. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2049–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.-X.; He, R.-Z.; Xu, Y.; Yu, X.-W. Oxidative stress tolerance contributes to heterologous protein production in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, A.; Liu, J.; Miao, T.; Zheng, F.; Rahim, K.; Lou, H.; Jiang, W. Characterization of two endo-β-1, 4-xylanases from Myceliophthora thermophila and their saccharification efficiencies, synergistic with commercial cellulase. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahmad, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Yin, T.; Deng, K.; Lu, C.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W. Efficient Expression of Lactone Hydrolase Cr2zen for Scalable Zearalenone Degradation in Pichia pastoris. Toxins 2026, 18, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010010

Ahmad M, Wang H, Liu X, Wang S, Yin T, Deng K, Lu C, Zhang X, Jiang W. Efficient Expression of Lactone Hydrolase Cr2zen for Scalable Zearalenone Degradation in Pichia pastoris. Toxins. 2026; 18(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Mukhtar, Hui Wang, Xiaomeng Liu, Shounan Wang, Tie Yin, Kun Deng, Caixia Lu, Xiaolin Zhang, and Wei Jiang. 2026. "Efficient Expression of Lactone Hydrolase Cr2zen for Scalable Zearalenone Degradation in Pichia pastoris" Toxins 18, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010010

APA StyleAhmad, M., Wang, H., Liu, X., Wang, S., Yin, T., Deng, K., Lu, C., Zhang, X., & Jiang, W. (2026). Efficient Expression of Lactone Hydrolase Cr2zen for Scalable Zearalenone Degradation in Pichia pastoris. Toxins, 18(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010010