Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: Outcomes on Uremic Toxins, Inflammation, and Vascular Calcification from Experimental and Clinical Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Experimental Model of Vascular Calcification in Rats

2.1.1. Changes in Kidney Function and Mineral Metabolism Parameters

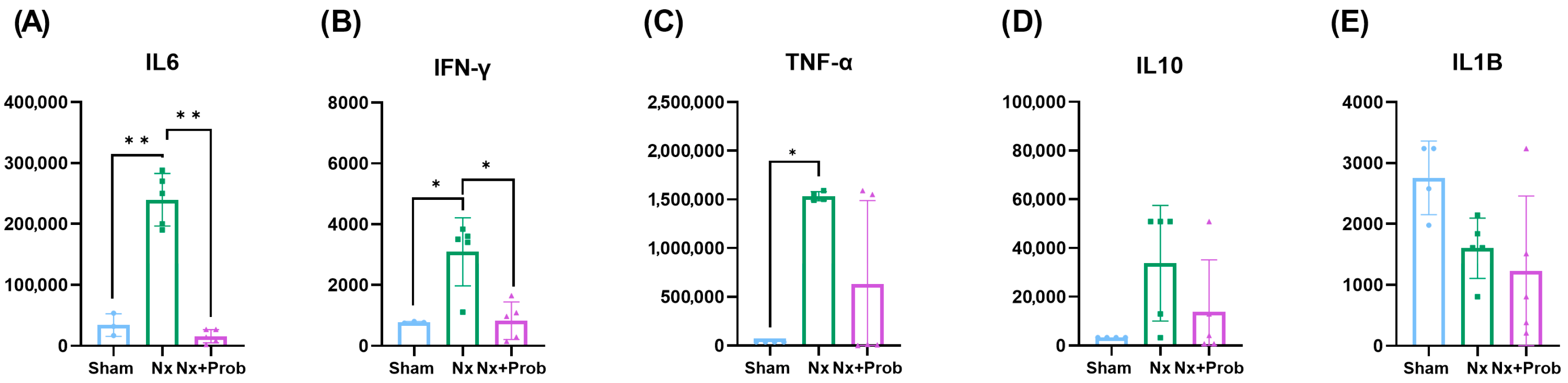

2.1.2. Inflammation in the Rat Experimental Model

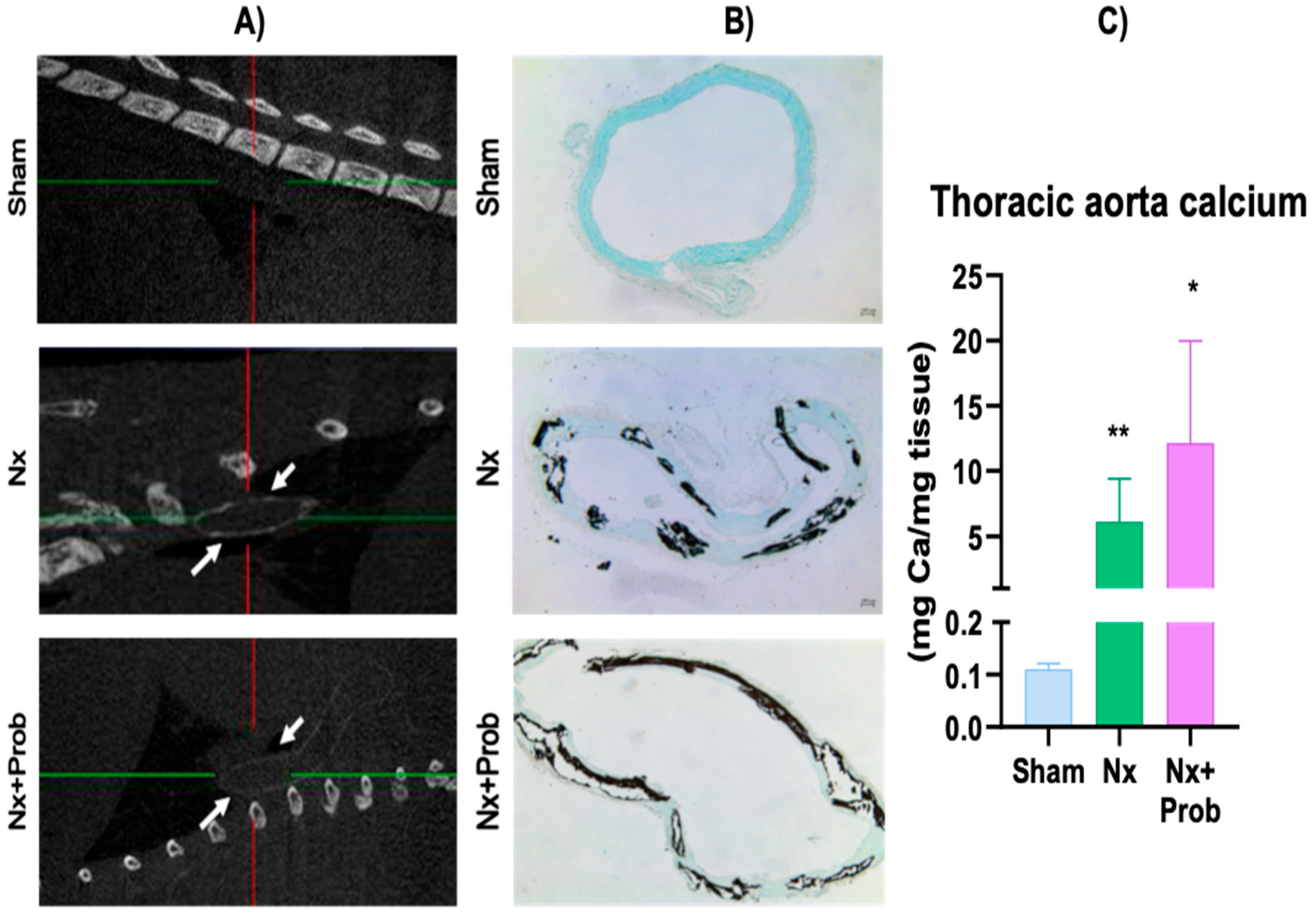

2.1.3. Vascular Calcification in the Rat Experimental Model

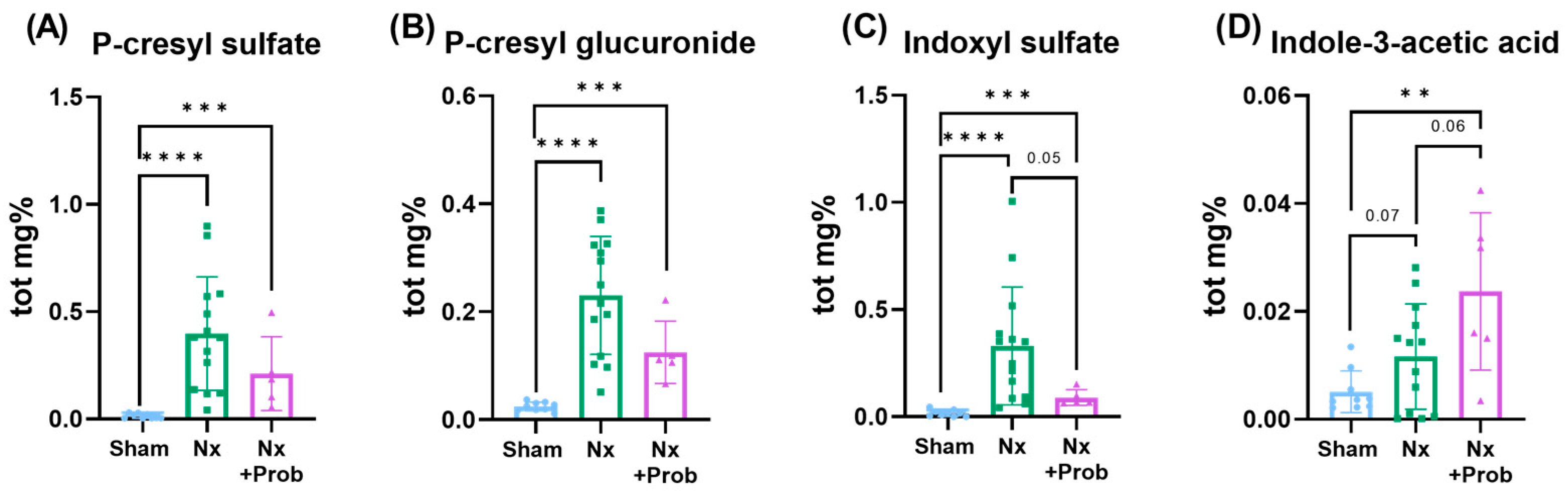

2.1.4. Quantification of Uremic Toxins in the Rat Experimental Model

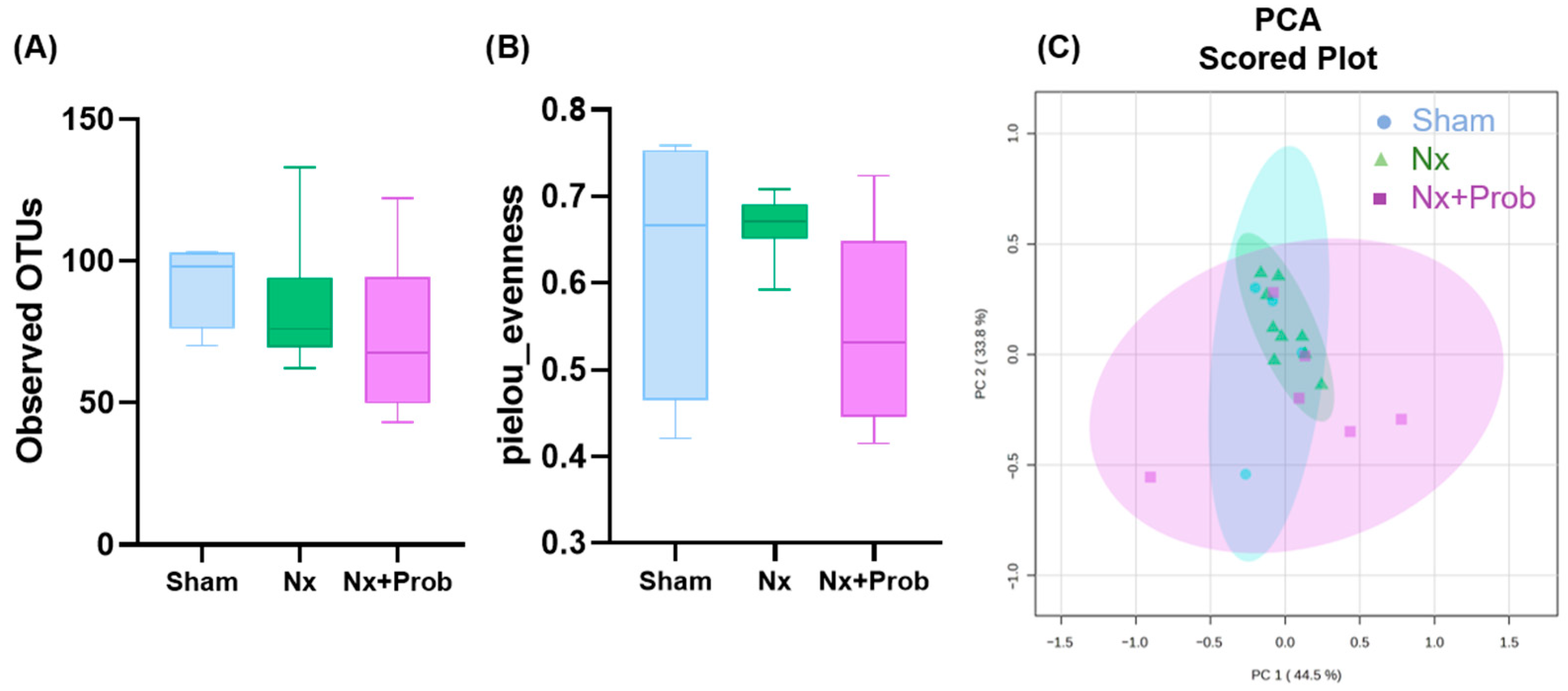

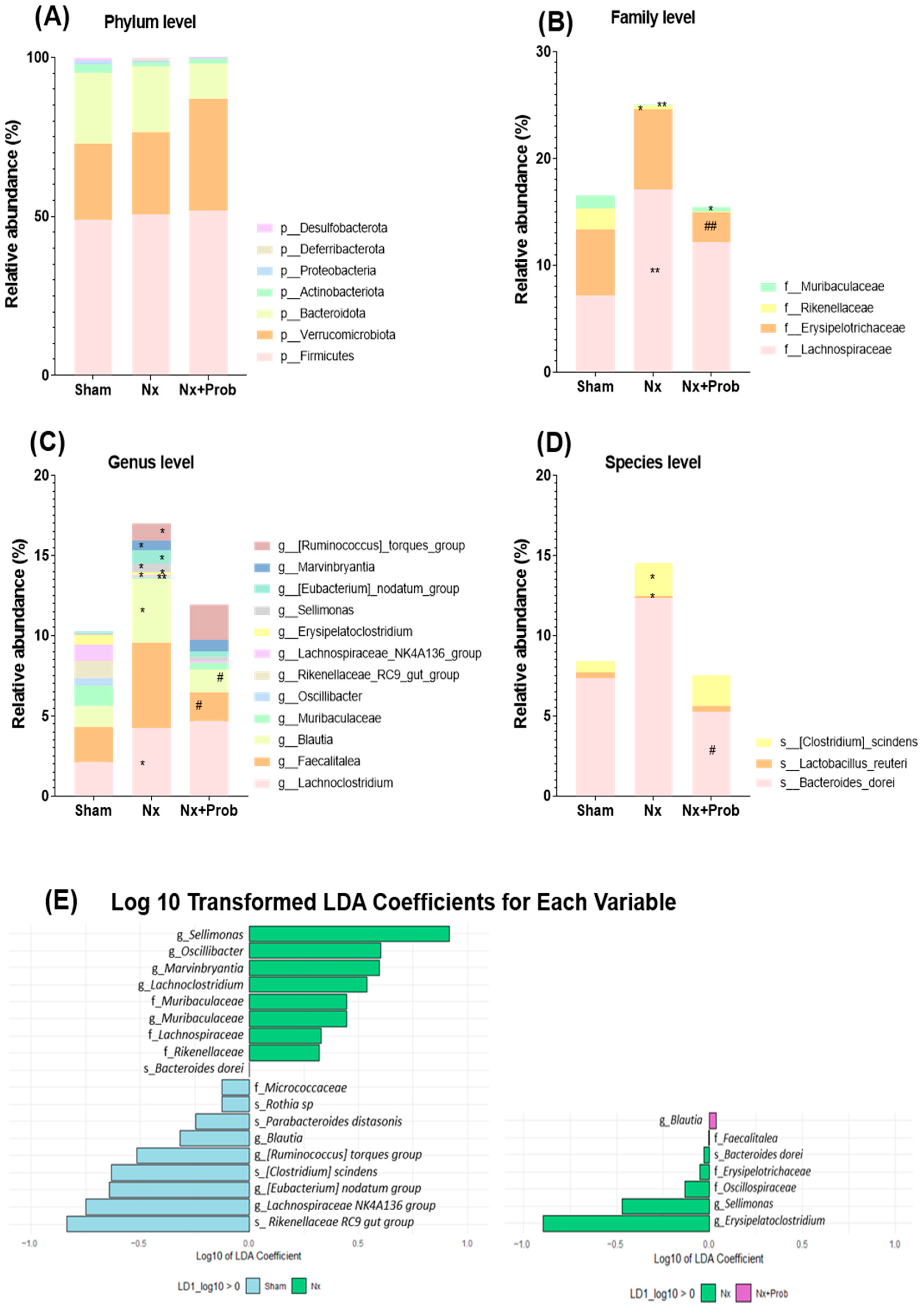

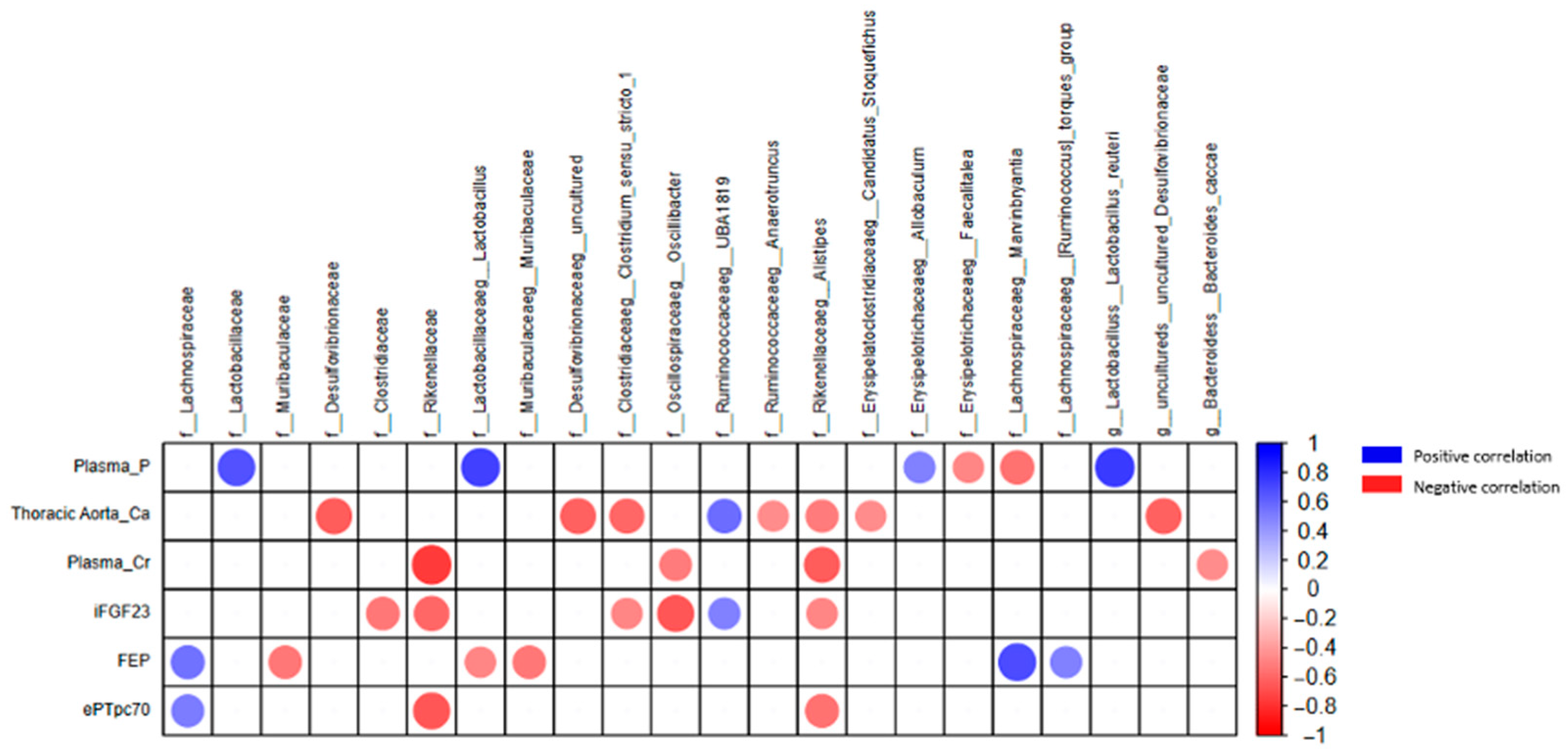

2.1.5. Characterizing Fecal Bacterial Diversity in the Rat Experimental Model

2.2. Clinical Study: Results

2.2.1. Kidney Function and Mineral Metabolism Parameters in Patients with CKD and VC

2.2.2. Inflammation Profile in Patients with CKD and VC

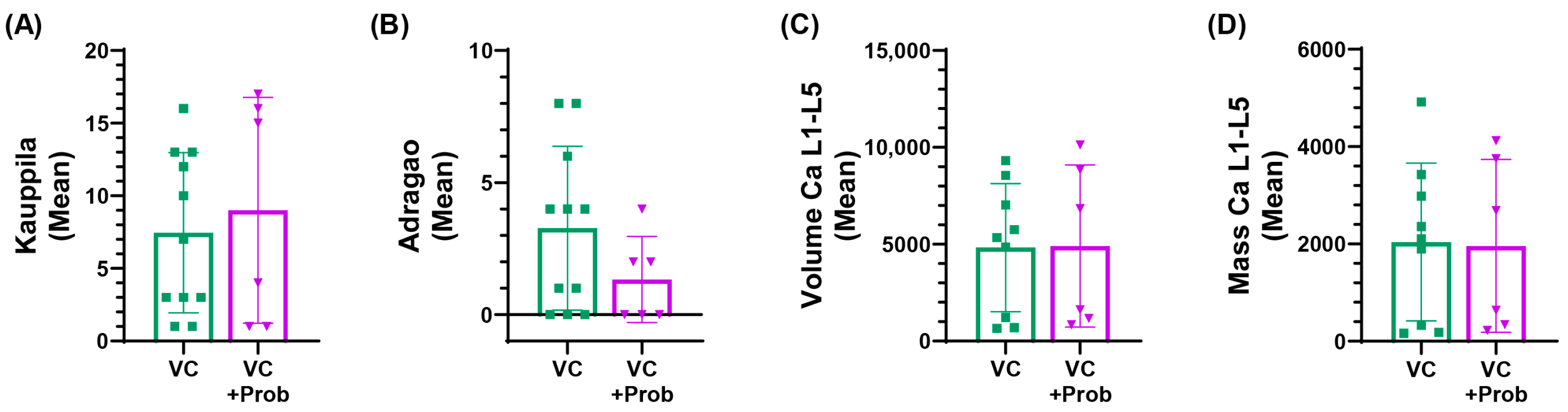

2.2.3. Vascular Calcification in Patients with CKD and VC

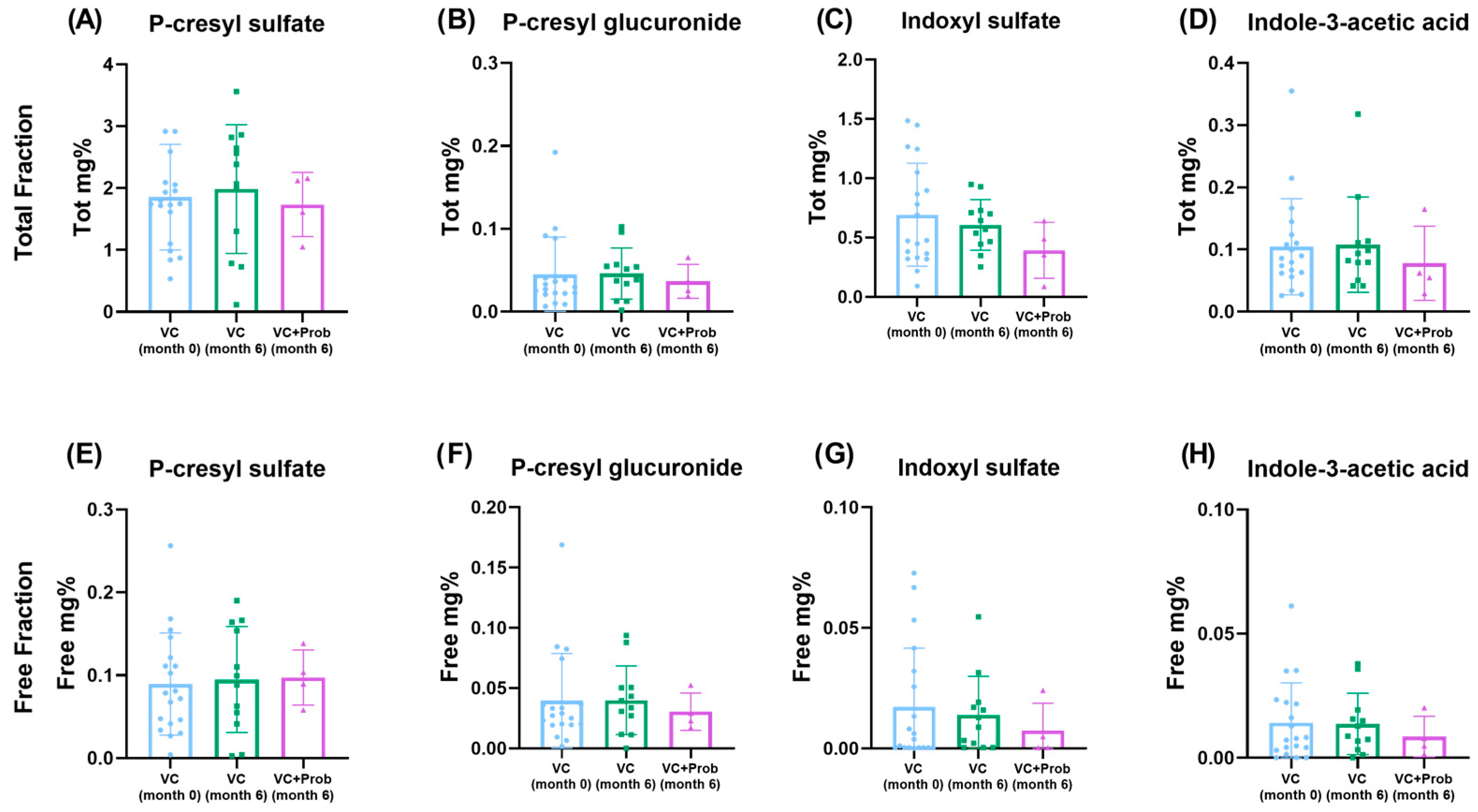

2.2.4. Quantification of Uremic Toxins in Patients with CKD and VC

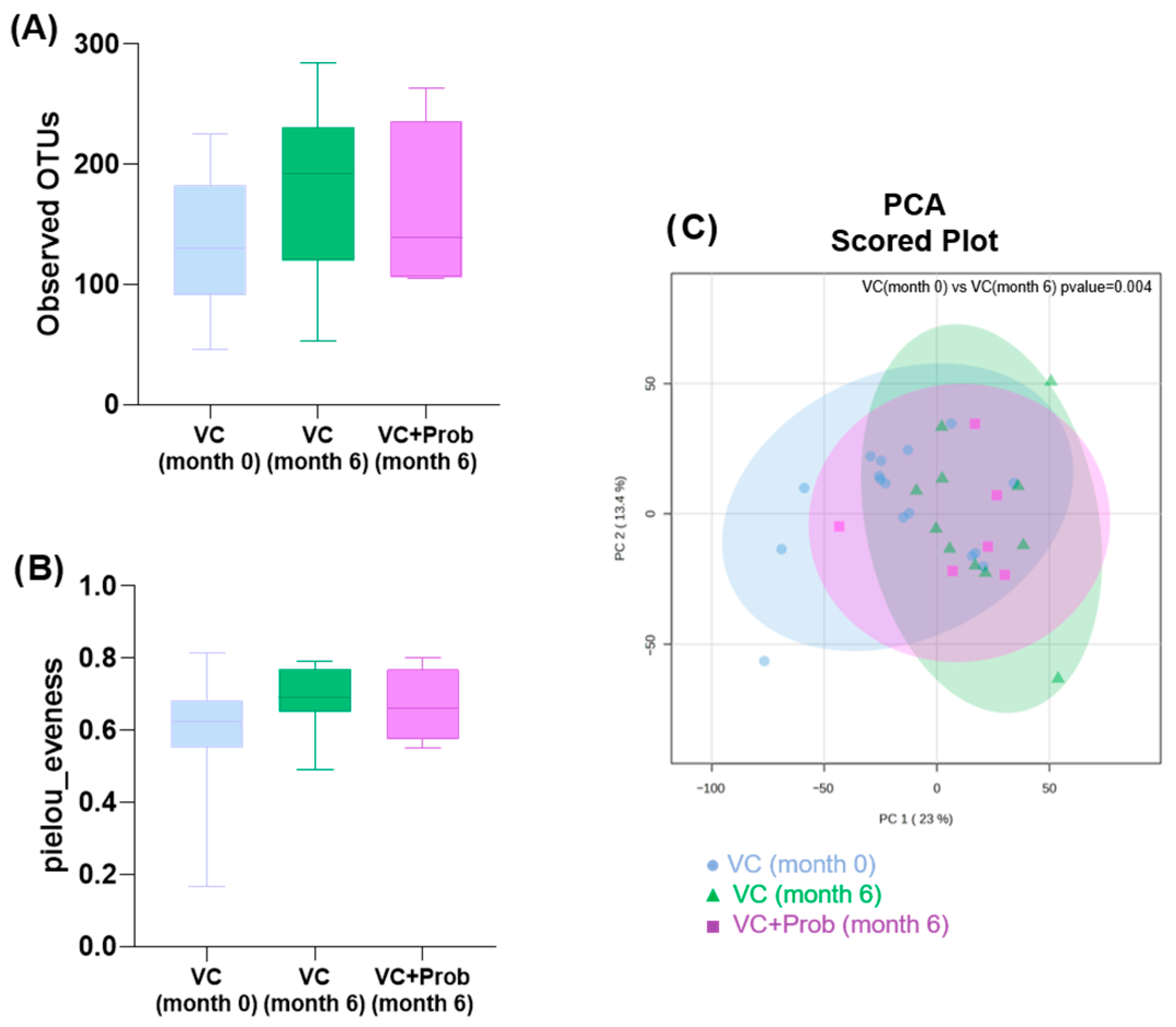

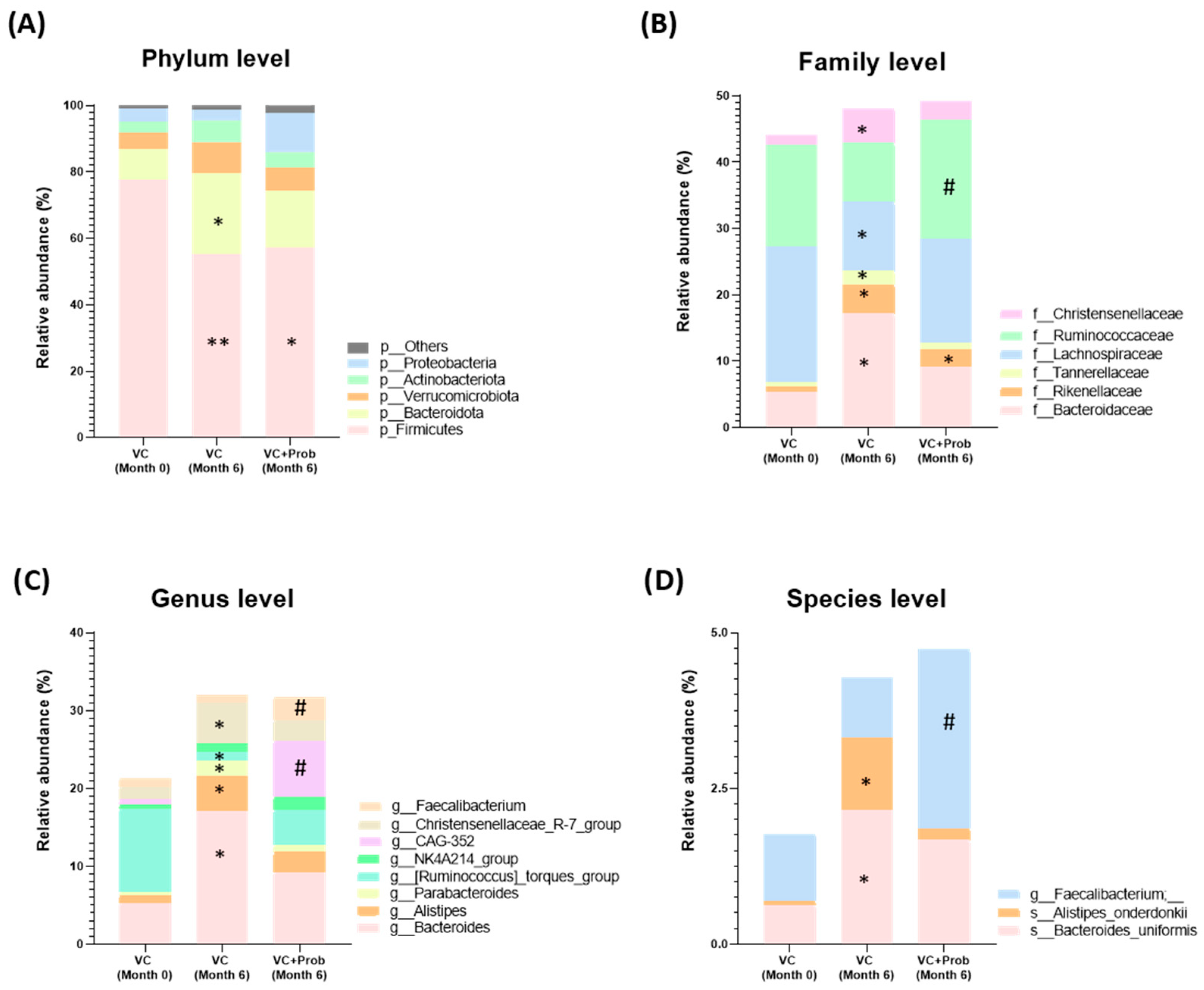

2.2.5. Characterization of Fecal Bacterial Diversity in Patients

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

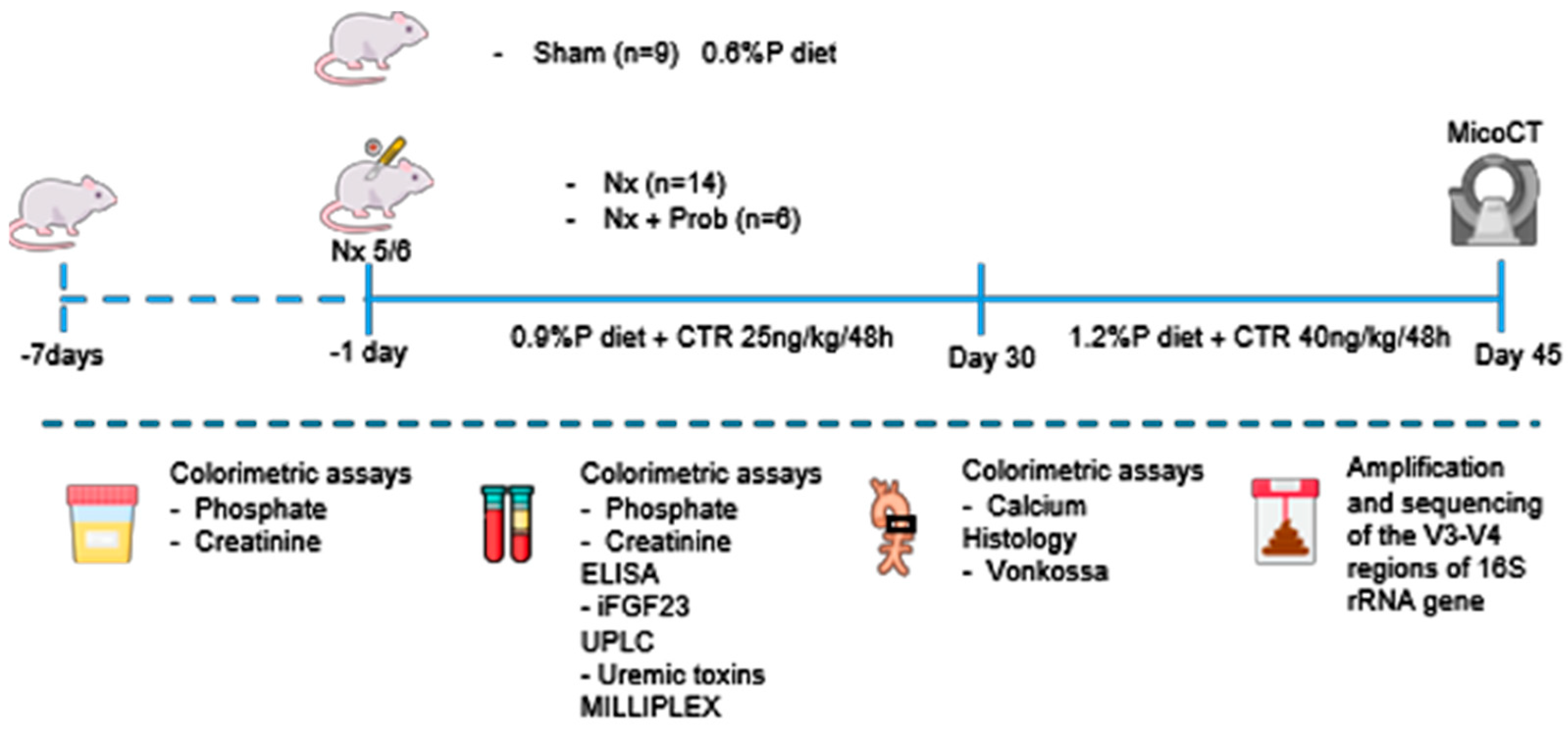

5.1. Experimental Study

5.1.1. Biochemical Measurements

5.1.2. Determination of Cytokines

5.1.3. Histology

5.1.4. Quantification of Calcium Content from Thoracic Aortas

5.1.5. Gut Microbiome Analysis in the Rat Experimental Model and in Patients from the Clinical Study

5.1.6. Quantification of Uremic Toxins Using UPLC (Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography) in Plasma Samples of the Rat Experimental Model and of the Patients from the Clinical Study

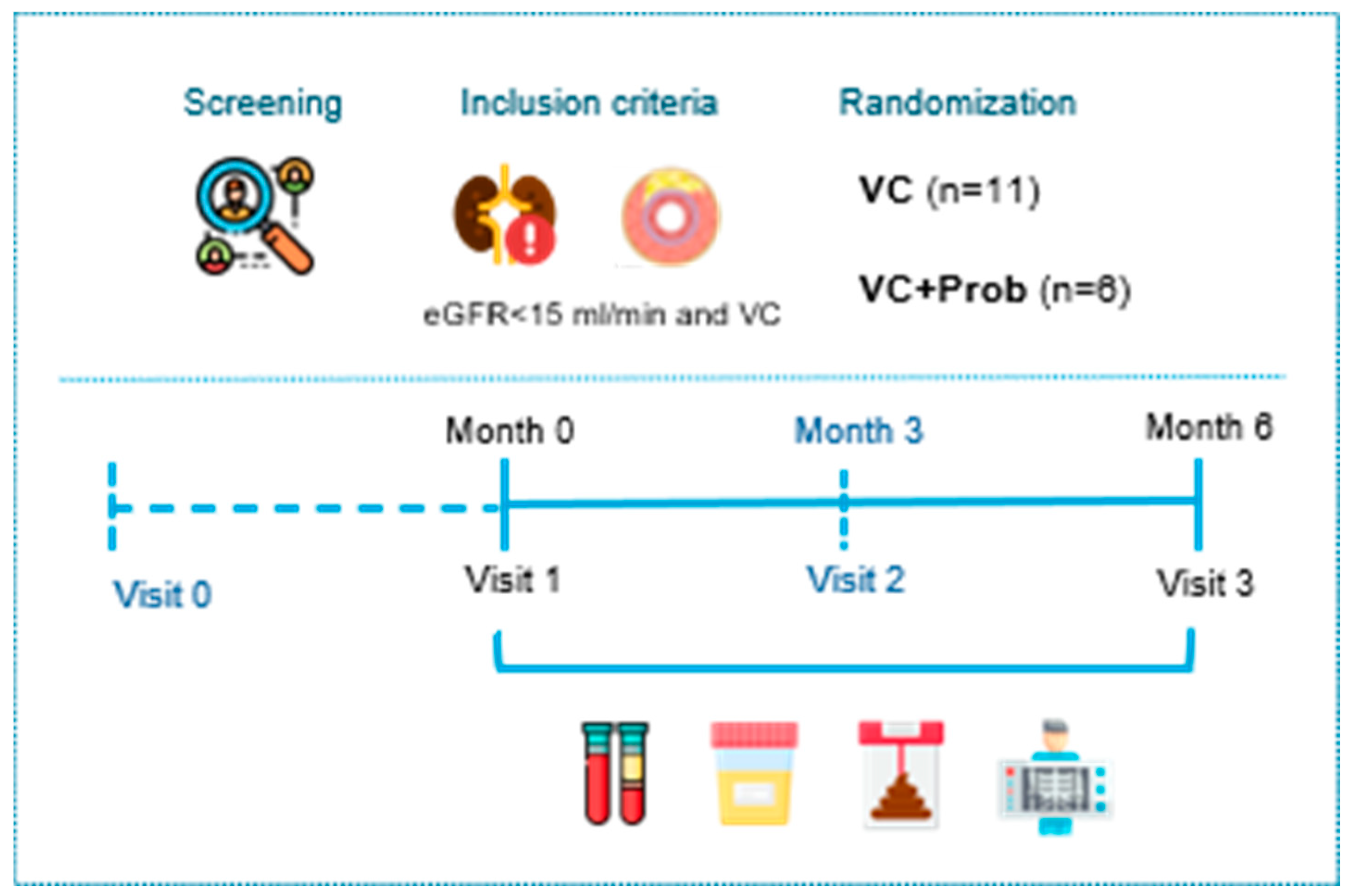

5.2. Clinical Study: Methods

5.2.1. Estimation of Nutritional Status

5.2.2. Blood and Urine Analysis

5.2.3. Assessment of Vascular Calcification in Patients

5.2.4. Inflammatory Profile in Patients

5.3. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| VC | Vascular Calcification |

| Nx | 5/6 Nephrectomy |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| VSMCs | Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells |

| P | Phosphate |

| IS | Indoxyl Sulfate |

| IAA | Indole-3-Acetic Acid |

| pCS | P-Cresyl Sulfate |

| pCG | P-Cresyl Glucuronide |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-Oxide |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| Micro-CT | Micro-Computed Tomography |

| iFGF23 | Intact Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 |

| Cr | Creatinine |

| RT | Room Temperature |

| V1 | Visit 1 |

| V3 | Final Visit |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| PEA | Proximity Extension Assay |

| FEP | Fractional Excretion of Phosphate |

| ePTpc70 | End-Proximal Tubule Phosphate Concentration |

| OTUs | Observed Operational Taxonomic Units |

| PCA | Unsupervised Principal Component Analysis |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| PP | Pulse Pressure |

| HT | Hypertension |

| DM | Diabetes |

| DL | Dyslipidemia |

| HU | Hyperuricemia |

| IHD | Ischemic Heart Disease |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| Ca | Calcium |

| PTH | Parathyroid Hormone |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| Alb | Albumin |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| UPLC | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IFN-γ | Interpheron-γ |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| PD | Peritoneal dialysis |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

References

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Global Public Health Agenda: An International Consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlacher, E.; Wollenhaupt, J.; Baaten, C.C.F.M.J.; Noels, H. Impact of Uremic Toxins on Endothelial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąk, W.; Dąbek, B.; Balcerczyk-Lis, M.; Motor, J.; Radzioch, E.; Młynarska, E.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Role of Uremic Toxins, Oxidative Stress, and Renal Fibrosis in Chronic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baaten, C.C.F.M.J.; Vondenhoff, S.; Noels, H. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Increased Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 970–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-P.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.-L. The Functional Role of Cellular Senescence during Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1330942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, P.; DeRiso, A.; Patel, M.; Battepati, D.; Khatib-Shahidi, B.; Sharma, H.; Gupta, R.; Malhotra, D.; Dworkin, L.; Haller, S.; et al. Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: Diversity in the Vessel Wall. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Bellosta, R. Vascular Calcification: Key Roles of Phosphate and Pyrophosphate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Giachelli, C.M. Vascular Calcification in CKD-MBD: Roles for Phosphate, FGF23, and Klotho. Bone 2017, 100, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Huo, J.; Chen, L. Bibliometric Analysis of the Relationship between Gut Microbiota and Chronic Kidney Disease from 2001–2022. Integr. Med. Nephrol. Androl. 2024, 11, e00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoultz, I.; Claesson, M.J.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Fåk Hållenius, F.; Konturek, P.; Korpela, K.; Laursen, M.F.; Penders, J.; Roager, H.; Vatanen, T.; et al. Gut Microbiota Development across the Lifespan: Disease Links and Health-promoting Interventions. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 297, 560–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, A.; Regolisti, G.; Brusasco, I.; Cabassi, A.; Morabito, S.; Fiaccadori, E. Alterations of Intestinal Barrier and Microbiota in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Ławiński, J.; Olszewski, R.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. The Impact of CKD on Uremic Toxins and Gut Microbiota. Toxins 2021, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanli, Z.; Vural, I.M.; Alp Avci, G. Chronic Kidney Disease, Uremic Toxins and Microbiota. Microbiota Host 2025, 3, e240012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, S.; Glorieux, G.; Vanholder, R. Uremic Toxins and Cardiovascular System. Cardiol. Clin. 2021, 39, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wu, Q.; Yao, Q.; Jiang, K.; Yu, J.; Tang, Q. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism and Multiple Effects on Cardiovascular Diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 81, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, H.; Tu, X.; Gao, Z. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids of Gut Microbiota Origin in Hypertension. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 730809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiola, M.; Koppe, L.; Larabi, A.; Thirion, F.; Lange, C.; Quinquis, B.; David, A.; Le Chatelier, E.; Benoit, B.; Sequino, G.; et al. Toxic Microbiome and Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease: Insights from a Longitudinal CKD-Microbiome Study. Gut 2025, 74, 1624–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchin, S.; Bertin, L.; Bonazzi, E.; Lorenzon, G.; De Barba, C.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Maniero, D.; Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Peng, D.; Kasimumali, A.; Rong, S. Gut Microbial Metabolites SCFAs and Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lv, D.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, J.; Liang, M.; Hou, F.; Chen, Y. Quantitative Reduction in Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Especially Butyrate, Contributes to the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 1857–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.-P.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.-T.; Sun, H.-H.; Liu, M.-D.; Zhou, H.-L.; Wang, Y.-S.; Xu, Z.-X. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Kumari, I.; Singh, B.; Sharma, K.K.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics: Safe Options for next-Generation Therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.D.C.S.O. Modulation of Intestinal Microbiota, Control of Nitrogen Products and Inflammation by Pre/Probiotics in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-W.; Chen, M.-J. Exploring the Preventive and Therapeutic Mechanisms of Probiotics in Chronic Kidney Disease through the Gut–Kidney Axis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 8347–8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-J.; Shan, Q.-Y.; Wu, X.; Miao, H.; Zhao, Y.-Y. Gut Microbiota Regulates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: A Double-Edged Sword in Renal Fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.J.; Hwang, J.; Kang, W.K.; Ahn, J.-P.; Kim, H.J. Administration of the Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus Paraplantarum Is Effective in Controlling Hyperphosphatemia in 5/6 Nephrectomy Rat Model. Life Sci. 2022, 306, 120856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, E.; Corr, S.C. Lactobacillus Spp. for Gastrointestinal Health: Current and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 840245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, L.; Dai, T.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, T.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ai, Y.; Ma, L.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Produced by Ruminococcaceae Mediate α-Linolenic Acid Promote Intestinal Stem Cells Proliferation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Q.; Shan, X.; Cai, C.; Hao, J.; Li, G.; Yu, G. Dietary Fucoidan Modulates the Gut Microbiota in Mice by Increasing the Abundance of Lactobacillus and Ruminococcaceae. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 3224–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyanti, M.; Andita, T.A.; Erlinawati, N.D.; Yunita, E.; Nasution, A.A.; Sari, K.; Massardi, N.A.; Putri, S.R. Probiotic Lactobacillus Acidophilus FNCC 0051 Improves Pancreatic Histopathology in Streptozotocin-Induced Type-1 Diabetes Mellitus Rats. Indones. Biomed. J. 2022, 14, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.-K.; Yen, T.-H.; Hsieh, P.-S.; Ho, H.-H.; Kuo, Y.-W.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-L.; Li, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Wang, J.-Y. Effect of a Probiotic Combination in an Experimental Mouse Model and Clinical Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pilot Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 661794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Li, L.; Ng, J.K.-C.; Li, P.K.-T. The Potential Benefits and Controversies of Probiotics Use in Patients at Different Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabico, S.; Al-Mashharawi, A.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Wani, K.; Amer, O.E.; Hussain, D.S.; Ahmed Ansari, M.G.; Masoud, M.S.; Alokail, M.S.; McTernan, P.G. Effects of a 6-Month Multi-Strain Probiotics Supplementation in Endotoxemic, Inflammatory and Cardiometabolic Status of T2DM Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhong, X.; Li, W.; Guo, T.; Ning, X.; Li, Z.; Ou, C. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Aggravates Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Potential Role for Extracellular Vesicles. Life Sci. 2023, 331, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Gai, Z.; Han, M.; Xu, J.; Zou, K. Reduction in Serum Concentrations of Uremic Toxins Driven by Bifidobacterium Longum Subsp. Longum BL21 Is Associated with Gut Microbiota Changes in a Rat Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Probiotics Antimicro. Prot. 2024, 17, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Miao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Wu, X.; Chen, L.; Guo, Y.; Zou, L.; Vaziri, N.D.; Li, P.; et al. Intrarenal 1-Methoxypyrene, an Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist, Mediates Progressive Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis in Mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 2929–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yang, N.; Yu, C.; Lu, L. Uremic Toxins Mediate Kidney Diseases: The Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Zou, L.; Guo, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, F.; Cao, G.; Zhao, Y. Lactobacillus Species Ameliorate Membranous Nephropathy through Inhibiting the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Pathway via Tryptophan-produced Indole Metabolites. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Microbial Tryptophan Catabolites in Health and Disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Niu, J.; Tang, X.-C.; Shan, L.-H.; Xiao, L.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Yin, L.-Y.; Yu, Y.-Y.; Li, X.-R.; Zhou, P. The Effects of Probiotic Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG on Fecal Flora and Serum Markers of Renal Injury in Mice with Chronic Kidney Disease. Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kafoury, B.M.; Saleh, N.K.; Shawky, M.K.; Mehanna, N.; Ghonamy, E.; Saad, D.A. Possible Protective Role of Probiotic and Symbiotic to Limit the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in 5/6th Nephrectomized Albino Rats. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.-N.; Yu, X.-Y.; Zhuang, S.; Guo, Y.; Vaziri, N.D.; Ma, S.-X.; Su, W.; Shang, Y.-Q.; et al. Targeting Lactobacillus Johnsonii to Reverse Chronic Kidney Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anegkamol, W.; Bowonsomsarit, W.; Taweevisit, M.; Tumwasorn, S.; Thongsricome, T.; Kaewwongse, M.; Pitchyangkura, R.; Tosukhowong, P.; Chuaypen, N.; Dissayabutra, T. Synbiotics as a Novel Therapeutic Approach for Hyperphosphatemia and Hyperparathyroidism in Chronic Kidney Disease Rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradi, V.; Caprara, C.; Barzon, E.; Mattarollo, C.; Zanetti, F.; Ferrari, F.; Husain-Syed, F.; Giavarina, D.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M. A Possible Role of P-Cresyl Sulfate and Indoxyl Sulfate as Biomarkers in the Prediction of Renal Function According to the GFR (G) Categories. Integr. Med. Nephrol. Androl. 2024, 11, e24-00002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Wu, V.; Wu, P.-C.; Wu, C.-J. Meta-Analysis of the Associations of p-Cresyl Sulfate (PCS) and Indoxyl Sulfate (IS) with Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Renal Failure. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Fu, P. Efficacy of Probiotics/Synbiotics Supplementation in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1434613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Merkling, T.; Metzger, M.; Koppe, L.; Laville, M.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Frimat, L.; Combe, C.; Massy, Z.A.; Stengel, B.; et al. Probiotic Intake and Inflammation in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: An Analysis of the CKD-REIN Cohort. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 772596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria Barros, A.; Borges, N.A.; Nakao, L.S.; Dolenga, C.J.; do Carmo, F.L.; de Carvalho Ferreira, D.; Stenvinkel, P.; Bergman, P.; Lindholm, B.; Mafra, D. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Inflammatory Biomarkers and Uremic Toxins in Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Patients: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, N.A.; Carmo, F.L.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; de Brito, J.S.; Dolenga, C.J.; Ferreira, D.C.; Nakao, L.S.; Rosado, A.; Fouque, D.; Mafra, D. Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Ren. Nutr. 2018, 28, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Stefanski, C.T.; Dolenga, C.; Nakao, L.S.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; De Moraes, T.P.; Moreno-Amaral, A.N. Pilot Study of Probiotic Supplementation on Uremic Toxicity and Inflammatory Cytokines in Chronic Kidney Patients. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 16, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastià, C.; Folch, J.M.; Ballester, M.; Estellé, J.; Passols, M.; Muñoz, M.; García-Casco, J.M.; Fernández, A.I.; Castelló, A.; Sánchez, A.; et al. Interrelation between Gut Microbiota, SCFA, and Fatty Acid Composition in Pigs. mSystems 2024, 9, e0104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Kong, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, G. A High-Fat Diet Increases Gut Microbiota Biodiversity and Energy Expenditure Due to Nutrient Difference. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-R.; Chou, T.-S.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hsiao, J.-K. A Potential Probiotic-Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 Group: Evidence from the Restoration of the Dietary Pattern from a High-Fat Diet. Res. Sq. 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, B.; Tang, T.; Xiao, Z.; Ye, F.; Li, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, J.-G.; Jiang, S. Gut Microbiota and Risk of Five Common Cancers: A Univariable and Multivariable Mendelian Randomization Study. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 10393–10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjabzadeh, D.; Bosch, J.A.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Ikram, M.A.; van Meurs, J.B.J.; Luik, A.I.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Lok, A.; van Duijn, C.M.; et al. Gut Microbiome-Wide Association Study of Depressive Symptoms. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Liao, S.-X.; He, Y.; Wang, S.; Xia, G.-H.; Liu, F.-T.; Zhu, J.-J.; You, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, L.; et al. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota With Reduced Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Level in Patients With Large-Artery Atherosclerotic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.Y.; Ha, C.W.Y.; Campbell, C.R.; Mitchell, A.J.; Dinudom, A.; Oscarsson, J.; Cook, D.I.; Hunt, N.H.; Caterson, I.D.; Holmes, A.J.; et al. Increased Gut Permeability and Microbiota Change Associate with Mesenteric Fat Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-N.; Yang, H.-W.; Hou, C.-Y.; Chang-Chien, G.-P.; Lin, S.; Tain, Y.-L. Melatonin Prevents Chronic Kidney Disease-Induced Hypertension in Young Rat Treated with Adenine: Implications of Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadsee, N.; Chuaypen, N.; Techawiwattanaboon, T.; Jinato, T.; Patcharatrakul, T.; Malakorn, S.; Petchlorlian, A.; Praditpornsilpa, K.; Patarakul, K. Identification of a Novel Gut Microbiota Signature Associated with Colorectal Cancer in Thai Population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, P.A.; Song, Y.; Liu, C.; Molitoris, D.R.; Vaisanen, M.-L.; Collins, M.D.; Finegold, S.M. Anaerotruncus Colihominis Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., from Human Faeces. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, F. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Restores Normal Fecal Composition and Delays Malignant Development of Mild Chronic Kidney Disease in Rats. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1037257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yu, H.; Fu, J.; Hu, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Bu, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; et al. Berberine Ameliorates Chronic Kidney Disease through Inhibiting the Production of Gut-Derived Uremic Toxins in the Gut Microbiota. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 1537–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini Khiabani, S.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Samadi Kafil, H. Chronic Kidney Disease and Gut Microbiota. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, T.; Hu, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, N. Changes in Gut Microbial Community upon Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, S.; Merckelbach, E.; Noels, H.; Vohra, A.; Jankowski, J. Homeostasis in the Gut Microbiota in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins 2022, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, A.; Stewart, L.; Blanchard, J.; Leschine, S. Untangling the Genetic Basis of Fibrolytic Specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in Diverse Gut Communities. Diversity 2013, 5, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, S.; Martín, R.; Rossi, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Chatel, J.M.; Sokol, H.; Thomas, M.; Wells, J.M.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii and Human Intestinal Health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, N.B.; Bryrup, T.; Allin, K.H.; Nielsen, T.; Hansen, T.H.; Pedersen, O. Alterations in Fecal Microbiota Composition by Probiotic Supplementation in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.; Hou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Shah, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Xia, X. Comparative Analysis of the Intestinal Microbiome in Rattus Norvegicus from Different Geographies. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1283453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, R.; Wang, S.; Solberg Woods, L.C.; Seshie, O.; Chung, S.T.; Shively, C.A.; Register, T.C.; Craft, S.; McClain, D.A.; Yadav, H. Comparative Microbiome Signatures and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Mouse, Rat, Non-Human Primate, and Human Feces. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fátima, G.P. Calcificación Vascular Asociada a Inflamación: Influencia de la Vitamina, D. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pendón-Ruiz De Mier, M.V.; Vergara, N.; Rodelo-Haad, C.; López-Zamorano, M.D.; Membrives-González, C.; López-Baltanás, R.; Muñoz-Castañeda, J.R.; Caravaca, F.; Martín-Malo, A.; Felsenfeld, A.J.; et al. Assessment of Inorganic Phosphate Intake by the Measurement of the Phosphate/Urea Nitrogen Ratio in Urine. Nutrients 2021, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novillo, C.; García-Saez, R.M.; Sánchez-Molina, L.; Rodelo-Haad, C.; Carmona, A.; Pinaglia-Tobaruela, G.; Membrives-González, C.; Jurado, D.; Santamaría, R.; Muñoz-Castañeda, J.R.; et al. The Phosphate/Urea Nitrogen Ratio in Urine—A Method to Assess the Relative Intake of Inorganic Phosphate. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sham | Nx | Nx + Prob | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 14 | 6 |

| Plasma P (mg/dL) | 3.90 ± 0.859 | 7.10 ± 3.367 * | 5.97 ± 4.238 |

| Plasma Cr (mg/dL) | 0.80 ± 0.141 | 1.56 ± 0.475 *** | 1.93 ± 1.208 ** |

| Urine Cr (mg/24 h) | 11.01 ± 3.606 | 9.26 ± 2.438 | 7.23 ± 2.141 * |

| FEP (%) | 53.0 ± 31.99 | 186.8 ± 89.65 *** | 169.1 ± 133.8 * |

| ePTpc70 (mg/dL) | 1.84 ± 0.735 | 11.62 ± 4.565 *** | 7.80 ± 4.196 * |

| iFGF23 (pg/mL) | 124.9 ± 51.92 | 22,586 ± 31,304 ** | 30,468 ± 28,336 ** |

| Control | VC | VC + Prob | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 11 | 6 | - |

| Age (years) | 61 ± 5 | 67 ± 10 | 64 ± 14 | 0.314 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 4.35 | 28.0 ± 7.07 | 27.4 ± 3.84 | 0.872 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 117.1 ± 16.62 | 150.3 ± 25.02 a | 143.5 ± 26.20 a | 0.007 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78.2 ± 7.50 | 81.6 ± 15.55 | 79.3 ± 13.00 | 0.817 |

| PP (mmHg) | 38.7 ± 11.19 | 68.5 ± 23.61 a | 64.0 ± 27.12 | 0.008 |

| Male (n/%) | 6/60 | 9/82 | 3/50.0 | 0.352 |

| HT (n/%) | 0/0 | 10/91 a | 6/100 a | 0.000 |

| DM (n/%) | 0/0 | 6/55 a | 3/50 a | 0.019 |

| DL (n/%) | 2/20 | 9/82 a | 6/100 a | 0.001 |

| HU (n/%) | 0/0 | 10/91 a | 5/83 a | 0.000 |

| Smoke (n/%) | 0/0 | 2/18 | 1/17 | 0.101 |

| IHD (n/%) | 0/0 | 3/27 | 1/17 | 0.211 |

| CVD (n/%) | 0/0 | 2/18 | 0/0 | 0.208 |

| Dialysis (n/%) | 0/0 | 5/46 (PD:3; HD:2) | 1/17 (HD:1) | 0.109 |

| VC (M 0) | VC (M 6) | VC + Prob (M 0) | VC + Prob (M 6) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr (mg/dL) | 4.02 ± 1.56 | 4.50 ± 1.06 | 3.85 ± 0.77 | 5.17 ± 2.28 | 0.398 |

| GFR (mL/min) | 18.67 ± 4.5 | 16.50 ± 3.72 | 17.20 ± 3.35 | 16.67 ± 3.20 | 0.711 |

| Mg (mg/dL) | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 2.05 ± 0.29 | 2.17 ± 0.15 | 2.25 ± 0.36 | 0.637 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 9.36 ± 0.86 | 9.06 ± 0.47 | 9.12 ± 0.63 | 8.60 ± 0.64 | 0.202 |

| P (mg/dL) | 5.02 ± 1.50 | 4.26 ± 1.05 | 4.48 ± 1.00 | 5.08 ± 1.34 | 0.474 |

| 1,25OHD (pg/mL) | 23.36 ± 14.49 | 21.50 ± 10.14 | 16.75 ± 4.86 | 18.67 ± 9.93 | 0.744 |

| 25OHD (ng/mL) | 26.78 ± 17.09 | 28.16 ± 9.66 | 30.07 ± 20.27 | 23.85 ± 4.52 | 0.893 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 237.24 ± 146.66 | 245.05 ± 133.59 | 348.78 ± 304.03 | 427.25 ± 314.75 | 0.315 |

| iFGF23 (pg/mL) | 1242.29 ± 1329.72 | 1133.99 ± 1154.37 | 405.21 ± 328.29 | 843.16 ± 886.76 | 0.464 |

| Prot/Cr (mg/g) | 1.80 ± 0.57 | 1.55 ± 0.53 | 1.84 ± 0.47 | 1.59 ± 0.78 | 0.782 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.20 ± 1.02 | 11.86 ± 1.55 | 11.73 ± 0.93 | 11.67 ± 1.98 | 0.855 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.34 ± 0.34 | 4.03 ± 0.39 | 4.32 ± 0.30 | 4.15 ± 0.36 | 0.232 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.27 ± 3.13 | 15.5 ± 33.73 | 4.00 ± 7.83 | 5.86 ± 5.57 | 0.461 |

| Iron (mg/dL) | 88.55 ± 46.14 | 56.13 ± 18.36 | 81.75 ± 28.88 | 68.00 ± 38.26 | 0.418 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 185.55 ± 196.90 | 213.162 ± 247.07 | 230.90 ± 355.09 | 54.04 ± 47.83 | 0.592 |

| DIET | VC (M 0) | VC (M 6) | VC + Prob (M 0) | VC + Prob (M 6) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate | 1058 ± 286.9 | 976.6 ± 250.8 | 982.1 ± 346.7 | 997.9 ± 144.3 | 0.943 |

| Calcium | 688.5 ± 213.1 | 552.6 ± 174.6 | 650.4 ± 305.8 | 738 ± 126.3 | 0.382 |

| Protein | 69,683 ± 20,270 | 62,099 ± 17,705 | 60,075 ± 11,152 | 59,453 ± 17,237 | 0.698 |

| Processed food | 64,185 ± 53,359 | 74,999 ± 78,017 | 82,138 ± 91,938 | 91,533 ± 92,831 | 0.911 |

| Soft drinks | 24.44 ± 73.33 | 0 ± 0 | 55 ± 134.7 | 33 ± 73.79 | 0.581 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Obrero, T.; Pendón-Ruiz de Mier, M.V.; Gordillo-Arnaud, J.E.; Jiménez Moral, M.J.; Vidal, V.; Guerrero, F.; Carmona, A.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, M.E.; Torralbo, A.I.; Ojeda, R.; et al. Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: Outcomes on Uremic Toxins, Inflammation, and Vascular Calcification from Experimental and Clinical Models. Toxins 2026, 18, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010006

Obrero T, Pendón-Ruiz de Mier MV, Gordillo-Arnaud JE, Jiménez Moral MJ, Vidal V, Guerrero F, Carmona A, Rodríguez-Ortiz ME, Torralbo AI, Ojeda R, et al. Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: Outcomes on Uremic Toxins, Inflammation, and Vascular Calcification from Experimental and Clinical Models. Toxins. 2026; 18(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleObrero, Teresa, María Victoria Pendón-Ruiz de Mier, Jose E. Gordillo-Arnaud, María José Jiménez Moral, Victoria Vidal, Fátima Guerrero, Andrés Carmona, María Encarnación Rodríguez-Ortiz, Ana Isabel Torralbo, Raquel Ojeda, and et al. 2026. "Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: Outcomes on Uremic Toxins, Inflammation, and Vascular Calcification from Experimental and Clinical Models" Toxins 18, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010006

APA StyleObrero, T., Pendón-Ruiz de Mier, M. V., Gordillo-Arnaud, J. E., Jiménez Moral, M. J., Vidal, V., Guerrero, F., Carmona, A., Rodríguez-Ortiz, M. E., Torralbo, A. I., Ojeda, R., Moyano, C., Sanchez-Ramade, M., Mesa, J., López-Ruiz, D. J., Valdés-Díaz, K., García-Sáez, R. M., Jurado-Montoya, D., Rodelo-Haad, C., Álvarez-Benito, M., ... Muñoz-Castañeda, J. R. (2026). Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: Outcomes on Uremic Toxins, Inflammation, and Vascular Calcification from Experimental and Clinical Models. Toxins, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010006