1. Introduction

Mycotoxins are naturally occurring small-molecule secondary molecules produced by certain mold species, primarily from

Alternaria,

Aspergillus,

Claviceps,

Fusarium, and

Penicillium genera, among others [

1]. The production of mycotoxins can occur globally in numerous crops and under a wide range of environmental and agronomic conditions, from field production through harvest, storage, and feed out. Some of the major factors affecting mycotoxin production include temperature, humidity, water activity, pH, aerobic conditions, fungal strain and microbial competition, substrate type and accessibility, and pest pressure [

2]. Generally, mycotoxins may be placed into the categories of regulated, masked, emerging, and storage mycotoxins [

3,

4,

5,

6], although these are not mutually exclusive. Regulated mycotoxins are those that are typically well-known and have action or guidance levels globally. Masked mycotoxins are those that have been biologically modified by plant defense mechanisms and sequestered following Phase-II and Phase-III metabolism [

5] and are more difficult to detect. Many emerging mycotoxins are produced by

Fusarium molds and historically escaped detection by conventional analytical techniques, although advanced methods are allowing for more routine detection and quantification [

3,

7]. Storage mycotoxins are primarily produced by the

Penicillium or

Aspergillus taxa and typically develop during feedstuff or feed storage [

4]. A few storage mycotoxins have regulatory guidelines in certain countries, but many mycotoxins in this group are not regulated.

Mycotoxins can be produced individually or in combination, where a single mycotoxin may be synthesized by multiple fungal species, a single mold can produce several distinct mycotoxins, and multiple different molds can be present on the same crop material [

1]. In the United States, it is reported that maize grain and maize silage may contain 4.8 to 5.2 different mycotoxins per sample, with some of the emerging and masked mycotoxins having higher occurrence rates than the typical regulated mycotoxins [

8]. In Europe, grains have been reported to contain up to 17 simultaneous mycotoxins [

6]. A survey from Asian countries that assessed the presence of 25 mycotoxins also showed high prevalence of multiple mycotoxin contamination (including emerging mycotoxins) in feedstuffs, with the majority of rice bran samples containing 7 mycotoxins (49.6%) and maize containing 5 mycotoxins (40.8%) [

3]. These survey results reflect the conclusion that multiple mycotoxin contamination is a common pattern globally in a variety of feedstuff types.

The consumption of individual mycotoxins by animals has been linked to a range of health and performance challenges. However, multiple mycotoxin mixtures can further increase the response due to heightened negative effects on intestinal health, immunity, and performance [

9]. Together, these negative effects pose a substantial economic burden to producers. A previous meta-analysis [

10] suggested that mycotoxin consumption in broilers could reduce the European Poultry Efficiency Factor by 22.5%, potentially resulting in an income loss of over EUR 1500 per flock. This estimate considered only reduced performance and increased mortality, excluding additional costs such as veterinary care. Due to the negative effects not only on animal health but also farm productivity and profitability, it is critical to understand the occurrence and co-occurrence of mycotoxins in animal feedstuffs to improve monitoring and mitigation programs. This study aimed to investigate prevalence, concentrations, and co-occurrence of 54 mycotoxins (11 groups) from the regulated, masked, emerging, and storage categories over a seven-year period, while also investigating the influence of feedstuff type and climatic region of Europe on these contamination patterns. This assessment of multiple mycotoxin contamination in several different crops by climatic regions of Europe is unique and could give insight into those regions with greater risk. Furthermore, co-occurrence patterns of mycotoxins were assessed through probabilistic co-occurrence modeling, which is of particular importance due to the combined influence of mycotoxins on animal performance and health. The information from this survey could help tailor local mycotoxin monitoring and mitigation by showing the mycotoxins that may be of primary importance to include in analysis programs and the potential risk for animals. Collectively, this survey may support a growing framework of knowledge looking to assess and predict mycotoxin risk by feedstuff type, growing region, and yearly environmental variability.

3. Discussion

Mycotoxin contamination of feeding materials for animals is common worldwide and may alter the quality of the commodity as well as the health, performance, and profitability of the animals consuming this material. Studies have shown that mycotoxin contamination can also contribute to raising the carbon footprint of production [

10,

11] through altered feed efficiencies and increased mortality rates. Furthermore, when considering the co-contamination of multiple mycotoxins, this could raise the risk to animal health and performance. While mycotoxin contamination of feedstuffs is the norm, as shown in both the current survey and previously published surveys [

8,

12,

13], the presence and concentrations of mycotoxins are also thought to be associated in part with climate change and altered agricultural practices [

14].

Mycotoxin content can vary by matrix type and is influenced by the European climatic region in which the crop was grown and stored. Across feedstuffs, maize grain contained the greatest mean number of mycotoxins, with 6.68 different mycotoxins per sample, followed by maize silage at 6.03. Maize is considered to be one of the most susceptible crops to pathogenic fungi [

14]. Interestingly, while maize products had the highest average number of mycotoxins across all samples and typically contained the highest detected maximums, this survey showed the prevalence of important regional variations. For example, barley in the Nordic region had the highest mean number of mycotoxins overall at 9.33, even though the mean number for barley across all regions combined was only 4.53 mycotoxins. Furthermore, barley was one of the feedstuffs, with the greatest number of mycotoxin groups (four groups) that significantly differed by region and had some of the highest average concentrations of mycotoxins within these groups. Within the Nordic region, all samples in this survey were from Finland. Barley is one of the most important crops produced in Finland, representing about one-quarter of the cultivated area [

15]. As such, the high prevalence and concentrations of mycotoxins in this feedstuff from this region could have significant health and economic effects.

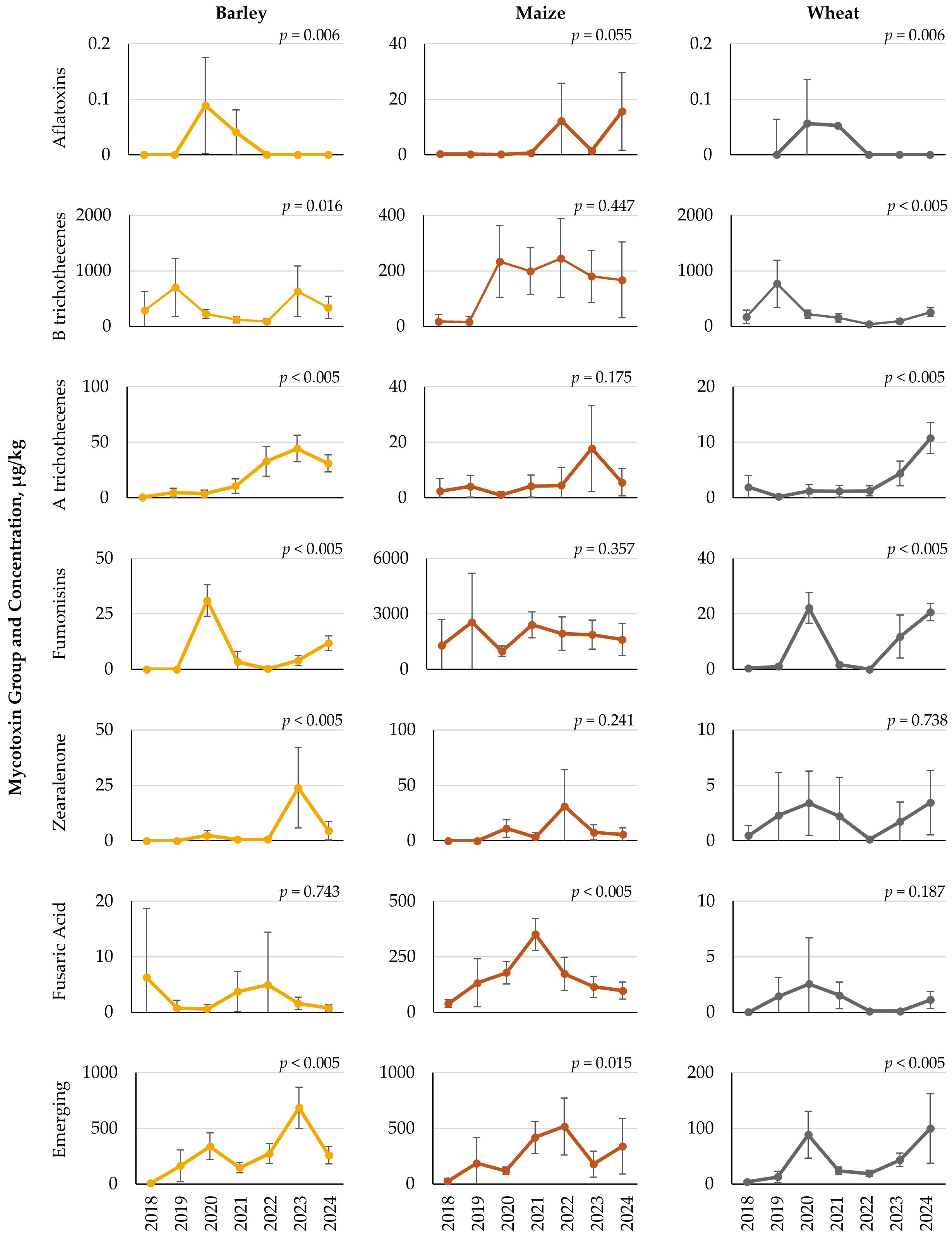

Significant yearly variations in mycotoxin content were observed across each feedstuff type. The small grains, barley and wheat, both showed yearly differences across a number of mycotoxin groups. In general, barley showed the highest mycotoxin concentrations in 2020 and 2023, while wheat results showed elevated concentrations of several mycotoxin groups in 2020 and 2024. Interestingly, both barley and wheat showed no difference in FA levels across years, with low concentrations and occurrence rates less than 10%. Maize, on the other hand, only had yearly differences for FA and emerging mycotoxins, with concentrations being highest in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Maize also contained a high occurrence rate of FA, with greater than 92% of the samples containing this mycotoxin, while occurrence rates of the various emerging mycotoxins were low. Maize silage samples were also impacted by year, with 2018 and 2023 generally having the highest concentrations, although yearly differences were not observed for B trichothecenes and FA, despite these being the two most prevalent mycotoxins. As such, it may be concluded that these two mycotoxin groups may be of constant presence in maize silage. More similar to the small grains, grass silage samples showed several yearly differences, with 2020 having several higher mycotoxin concentrations.

When looking across years, feedstuffs, and mycotoxins, it may be summarized that 2020 and 2023 were among the years that showed the highest mycotoxin concentrations, particularly for the small grains and grass silage. Europe is reported to be the fastest warming continent [

16]. The Copernicus Climate Change Service report [

16] for Europe states that 2024 was the warmest year on record since 1900, followed by 2020 and 2023. Furthermore, in 2024, 34% of the land area experienced above-average precipitation, while in 2023, about 7% of the land area experienced above-average precipitation. Although the results from this mycotoxin survey have not been correlated with any statistical model, it may be suggested that feedstuffs such as barley, wheat, and grass silage could have increased mycotoxin occurrence during years of elevated temperature stress. In contrast, mycotoxin contamination of maize and maize silage may be promoted by different weather patterns, notably the slightly lower (although still above-average) temperatures observed in years other than 2020, 2023, and 2024 [

16]. In addition to temperature and precipitation amount, it should also be remembered that the timing of these weather events during plant and grain development is also critical [

17]. Although the year 2025 is not complete at the time of this survey, reports indicate that 2025 had the fourth warmest summer (June to August) for the European continent, with pronounced variation in precipitation among regions [

18]. As such, it may be expected that mycotoxin risk will continue to increase. Although the conclusions from this survey regarding mycotoxin variation by climatic region and year are largely speculative due to a lack of detailed and local weather (temperature, precipitation) data, these results do provide a starting point for concepts to investigate. Further research is needed to link location data, mycotoxin results, and weather patterns to have a more accurate understanding of climate influence and mycotoxin predictions.

Identifying patterns of co-occurrence for groups of mycotoxins may spur further research and insights. Co-occurrence is investigated under a null (random) model that tests if there are combinations of pairs that show significant positive or negative associations [

19]. These associations, or patterns of species occurrence, can provide insight into the pair’s relationships within the environment, as they relate to habitat, competition, symbiotic relationships, etc. Positive associations represent the co-occurrence of pairs that appear greater than random chance, suggesting that a pair of mycotoxin groups co-occurred together more than expected in that environment. This positive co-occurrence may be due to a similarity in mold species producing those mycotoxins, a mold producing more than one mycotoxin, or similar environmental stimuli promoting the production of varying mycotoxin groups, among other factors. On the other hand, negative associations are those where species occur less often than expected by random chance, often due to species competition, avoidance, or sequential matrix-associated evolution [

19]. In relation to mycotoxins, this may occur among molds that require differing environmental conditions to grow or produce mycotoxins [

20]. Further investigation of species attributes can provide information on the contribution of the individual group to the positive, negative, or random associations, and indicate whether the co-occurrences are evenly distributed among groups rather than clustered within a few groups [

21]. With this data, results may give insights into the types of mycotoxins expected to be found on each commodity, as well as the likelihood of mycotoxins coming from

Fusarium,

Penicillium,

Aspergillus, or

Claviceps species.

The results obtained in this research showed that there were more significant deviations from random expectations for grains than for silages, with grains having mostly positive deviations (40 positives versus 7 negatives). Across all grains and maize silage, the highest probabilities of co-occurrence (both positive and non-significant) were between mycotoxin groups produced primarily by

Fusarium molds. Notably, FA and emerging mycotoxins were highly co-occurring with B trichothecenes.

Fusarium represents a large group of mold species, which produce numerous mycotoxins including B and A trichothecenes, FUMs, ZEA, FA, beauvericin, ENN, and MON [

14]. Furthermore, some mycotoxins such as FA or MON are reported to be produced by more than 12 and 30

Fusarium species, respectively [

22,

23]. In this survey, there were high positive co-occurrence rates between B trichothecenes and FA in maize and maize silage, with 55.9% and 86.3%, respectively, indicating that these two mycotoxin groups are not only common in maize-based commodities but also may be promoted by similar environmental conditions. Maize and maize silage also contained high co-occurrence of B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins (52.4% and 74.2%) and FA and emerging mycotoxins (80.8% and 68.1%), although these were associated with the models’ random expectations. Interestingly, although B trichothecenes are a highly co-occurring group, they only contributed to 22% of all positive pairs, showing that they are highly occurring but at rates expected by the models. Across previously published surveys, mycotoxin members of the B trichothecenes are found to be highly occurring [

6,

24].

It is interesting to note that AFs had low occurrence rates across matrix types, at rates of less than 2.7% of samples having AFs above LOD, with the exception of maize that had the occurrence of AFs up to 13%. At the same time, co-occurrences of AFs with other mycotoxins were also low, with an observed maximum (random association) between AFs and FA in maize at 12.7%. Furthermore, analysis of AFs by year was marked by only certain years, with elevated concentrations across feedstuffs. The lower occurrence rates of AFs may reflect a more sporadic production pattern, with episodic spikes driven by periods of elevated temperatures and water activity (a

w)—conditions that have recently become more common in parts of Europe [

2,

16]. Due to the low detection frequency of AFs, establishing robust co-occurrence patterns has been more challenging. Nevertheless, these toxins remain highly relevant as they constitute the only mycotoxin category with enforced regulatory limits. In this survey, levels of AFs were detected above permissible thresholds in some cases, in particular for maize and maize silage (maximum values of 451 µg/kg and 152 µg/kg).

Emerging mycotoxins play an important role in observed mycotoxin co-occurrences. In barley, the highest co-occurrence was for B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins at 60.9% (positive), showing that these mycotoxins often occur together and at rates above random chance. Previous surveys have also found high rates of emerging mycotoxins in barley [

25]. Interestingly, although emerging mycotoxins had a high co-occurrence with B trichothecenes, this mycotoxin group contributed only 10% to all positive co-occurrences, indicating that in the majority of interactions, these mycotoxins were at expected rates. Wheat was similar to barley regarding co-occurrences, with the highest co-occurrences between B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins at 52.9% (positive). Wheat was similar to barley regarding co-occurrences, with the highest co-occurrences between B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins at 52.9% (positive).

The key emerging mycotoxins detected in barley and wheat, as well as maize silage, were ENN A/A1 and ENN B/B1 at 54 to 75% occurrence rates. In contrast, maize grain had a higher occurrence of MON than ENN. There are numerous mycotoxins that fall into this ‘emerging’ category, including, for example, several produced by

Alternaria species such as tenuazonic acid, alternariol monomethyl ether, and altertoxin [

26]. Although the current survey only included one

Alternaria toxin (alternariol), it covered many of the key emerging mycotoxins (such as ENN A/A1, ENN B/B1, and MON). These emerging mycotoxins can be produced by multiple mold species, but it is reported that ENN is most favorably produced at a

w and temperature combinations of a

w 0.994/25 °C, while MON production occurs more readily at lower moisture levels of a

w 0.960/25 °C [

27]. The production of DON by

F. graminearum is also similar at a

w 0.960/25 °C, supporting the high co-occurrence of these mycotoxins. Due to these high rates of co-occurrence, the potential for feedstuffs to be contaminated with multiple mycotoxins may be considered the norm. For the animal industry, mycotoxin co-contamination is of importance as the consumption of multiple mycotoxins increases the total risk to cause greater negative effects on health or performance through additive or potential synergistic relationships [

9,

28,

29,

30]. Pertaining specifically to the interactions of DON with ENN, MON, or FA, there are a limited number of references, with those that are available cover only a few animal species and lack investigation with naturally contaminated feed materials. Generally, trials investigating DON with ENN or MON report neutral (non-related) or additive-type interactions [

31,

32]. In contrast, the presence of DON with FA is considered to vary widely between neutral, additive, and synergistic [

33,

34]. Given their high co-occurrence, further research on the combined toxicity of these mycotoxins under natural contamination scenarios and across different animal species is warranted. Such work could help explain discrepancies observed among naturally contaminated matrices containing unaccounted mycotoxins (e.g., FA) and controlled, single-toxin dietary challenge studies.

In contrast to the cereal grain-based commodities, grass silage had a pattern of few positive and more negative associations, which may indicate that grass has a pattern of mold growth differing from that of other commodities, in part due to the grass substrate composition, growing conditions, harvest timing, and storage management. Generally, grass silage had lower co-occurrence rates of mycotoxins than the other feedstuff types, shown, for example, with the co-occurrence rate for B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins at only 28.8% and having a negative relationship. This negative association indicates that these two groups are occurring less than model expectations or less than observed by random chance in nature. In fact, many of the

Fusarium mycotoxins occurred less in grass silage than expected. These results may be supported by previous research showing that grass silage contained fewer fungal metabolites (mean 20; range 12 to 27) out of 106 analyzed, whereas maize silage contained a mean of 26 (range 19 to 64) fungal metabolites [

35].

There are several unknown factors related to the growth and production of grass silage samples assessed in this survey. As such, some level of caution may be warranted when considering the variability and traceability of mycotoxin risk in grass silage (and similarly maize silage) in this longitudinal survey. For example, it is unknown whether the cut number or harvest timing was consistent across grass silage samples. It is also unknown as to which species of grass were used for each silage sample. Grass species used to make this forage source can vary widely across Europe, which may influence the associated susceptibility to different types of molds, although this has not been statistically confirmed [

36]. Moreover, the duration and conditions of storage before analysis, which can markedly influence both the total mycotoxin load and the pattern of co-occurrence present at the time of consumption, were not captured.

Previous research has demonstrated that the timing of cutting and storage conditions may have the greatest influence on mycotoxin (such as DON, ZEA, and T2) content in grass silage [

36]. For example, DON content of grass harvested in the Czech Republic was shown to be lower in June than from late July to October, although it should be noted that overall each cutting had relatively low concentrations of DON with a maximum mean of 51.9 µg/kg [

36]. As such, harvest times could have played a role in the deviation from the expected occurrence of B trichothecenes in the current survey, but it also may be concluded that these mycotoxins may in fact be occurring less and at lower concentrations in this commodity than others [

35]. Perhaps of more importance is the effect of ensilaging, which was shown by [

36] to increase DON content by about 408% (up to 167.7 µg/kg). Alternatively, in the current survey, the highest co-occurrence rate of 32.1% was found for FA and the

Penicillium mycotoxins group (positive), which was much greater than for other matrix types. This high rate of

Penicilliums in grass silages is supported by previous work [

4,

35].

Penicillium molds typically favor growth and production of mycotoxins on crops post-harvest, being able to grow under a wide range of environmental conditions that include lower a

w (0.79–0.83), pH (3.0–6.0), and oxygen (1%) levels [

37]. However, these molds can also grow and produce mycotoxins on crops pre-harvest when wet conditions occur in the field [

38]. The majority of grass silage samples originated in the Oceanic and northern Continental regions, where grass silage is typically collected over several cuttings from May to August [

39,

40]. Due to this wide range of harvest time and processing, this commodity could be exposed to a variety of environmental conditions. Furthermore, grass silage must undergo proper fermentation for best storage quality. Silage that has lower dry matter and slower fermentation has been correlated with increased mycotoxin risk [

41]. Due to the difference in production and the influence of both field and storage, this feedstuff may have a different mycotoxin profile from the cereal-based commodities.

4. Conclusions

This survey of European grains and forages provides insight into mycotoxin concentrations, occurrence, and co-occurrence between 2018 and 2024. Although it represents only a snapshot of a mycotoxin surveillance program, this survey can be used to understand potential future risk of mycotoxin contamination in animal feedstuffs and ingredient commodities. Furthermore, this survey provides novel insight into mycotoxin profiles according to the European climatic region and mycotoxin co-occurrence patterns for a wide range of mycotoxins including those in the emerging mycotoxin and storage mycotoxin categories.

It has now been established that it is the norm rather than an exception for grains and forages to contain multiple mycotoxins. Maize contained the greatest diversity of mycotoxin, averaging 6.68 distinct toxins per sample, while grass silage contained the lowest average at 3.07. Climatic region played an important role in the observed number of mycotoxins and mycotoxin concentrations. Surprisingly, barley from the Nordic region was one of the more contaminated feedstuffs, with an average of 9.33 mycotoxins per sample and the highest mean and maximum concentrations for several mycotoxin groups including B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins. Harvest year also played a role in observed mycotoxin content. In general, small grains and grass silage appeared to have greater mycotoxin risk in 2020, 2023, and 2024, which were years marked by higher average temperatures across Europe, along with elevated rainfall in some regions. Both barley and wheat had high co-occurrence of B trichothecenes and emerging mycotoxins. However, grass silage had the highest co-occurrence of Penicillium mycotoxins with FA. In contrast, maize and maize silage appeared to have different contamination patterns. Maize had the highest co-occurrence between FUMs and FA or emerging mycotoxins and appeared to have higher concentrations in 2021 and 2022. Maize silage had the highest co-occurrence of B trichothecenes and FA, with generally increased risk in 2018 and 2023. As such, it may be concluded that mycotoxin occurrence and content vary by feedstuff type, region, and year, which may be expected due to varied environmental conditions. Future research is needed to better model and predict the relationship between climate and mycotoxins.

The presence of multiple mycotoxins in different feedstuffs of European origin appears to be the norm and could increase the risk of mycotoxins to animal performance and health. Furthermore, the combination of several feedstuffs containing multiple mycotoxins can further increase risk and result in final mycotoxin intake well above the guidelines suggested by government or regulatory groups. The knowledge gained from this survey may help to support and advance mycotoxin monitoring and mitigation programs. For example, local mycotoxin testing may be tailored based upon those mycotoxins that more frequently occur in that climatic region or feedstuff, including not only the regulated but also masked, emerging, or storage mycotoxins. Maize-based commodities should be generally considered to have the greatest mycotoxin contamination, with the exception of barley from the Nordic climatic region. Furthermore, results demonstrated high mycotoxin co-occurrence, indicating a need for not only an increase in the number of mycotoxins routinely analyzed by individuals and regulatory groups, but also an awareness for a potential increase in negative effects on animals. The high co-occurrence rates of B trichothecenes with FA and emerging mycotoxins should be noted and may suggest a need for continued research aimed at understanding the effects of these mycotoxin groups together on animal performance and health under natural and common contamination levels. Overall, the detection, quantification, and assessment of multiple mycotoxins in feedstuffs should be considered a routine component of a mycotoxin monitoring program, with consideration of management strategies that reduce mycotoxin risk to and within the animal.