Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Modulate Platelet Response During Storage of Platelet Concentrates and Impair Silkworm Survival

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Staphylococcus aureus Heightens Platelet Activation During Storage of S. aureus-Contaminated PCs

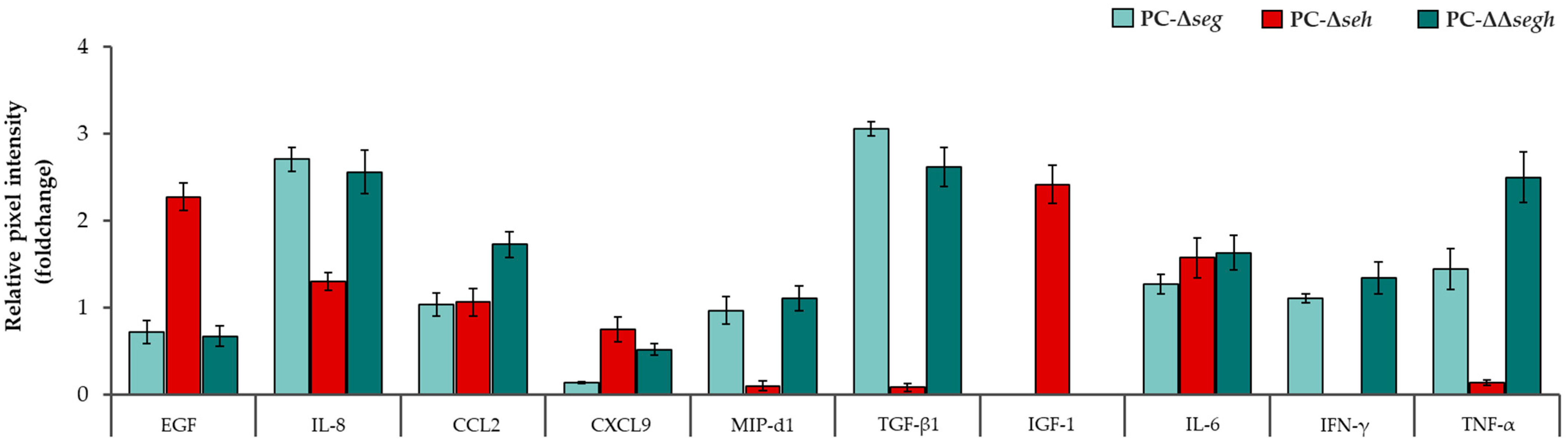

2.2. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Exacerbate a Pro-Inflammatory Profile in Platelets During PC Storage

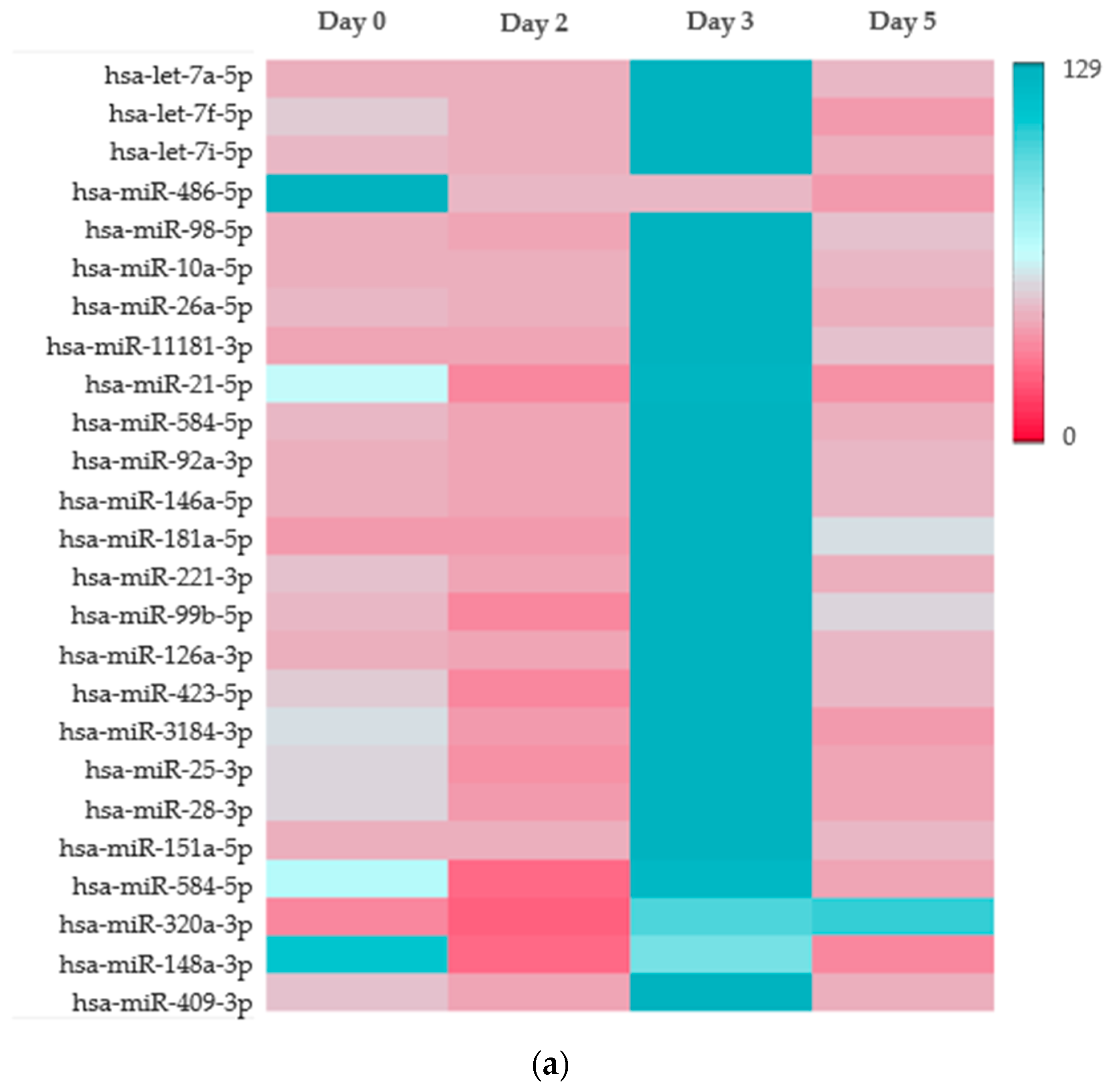

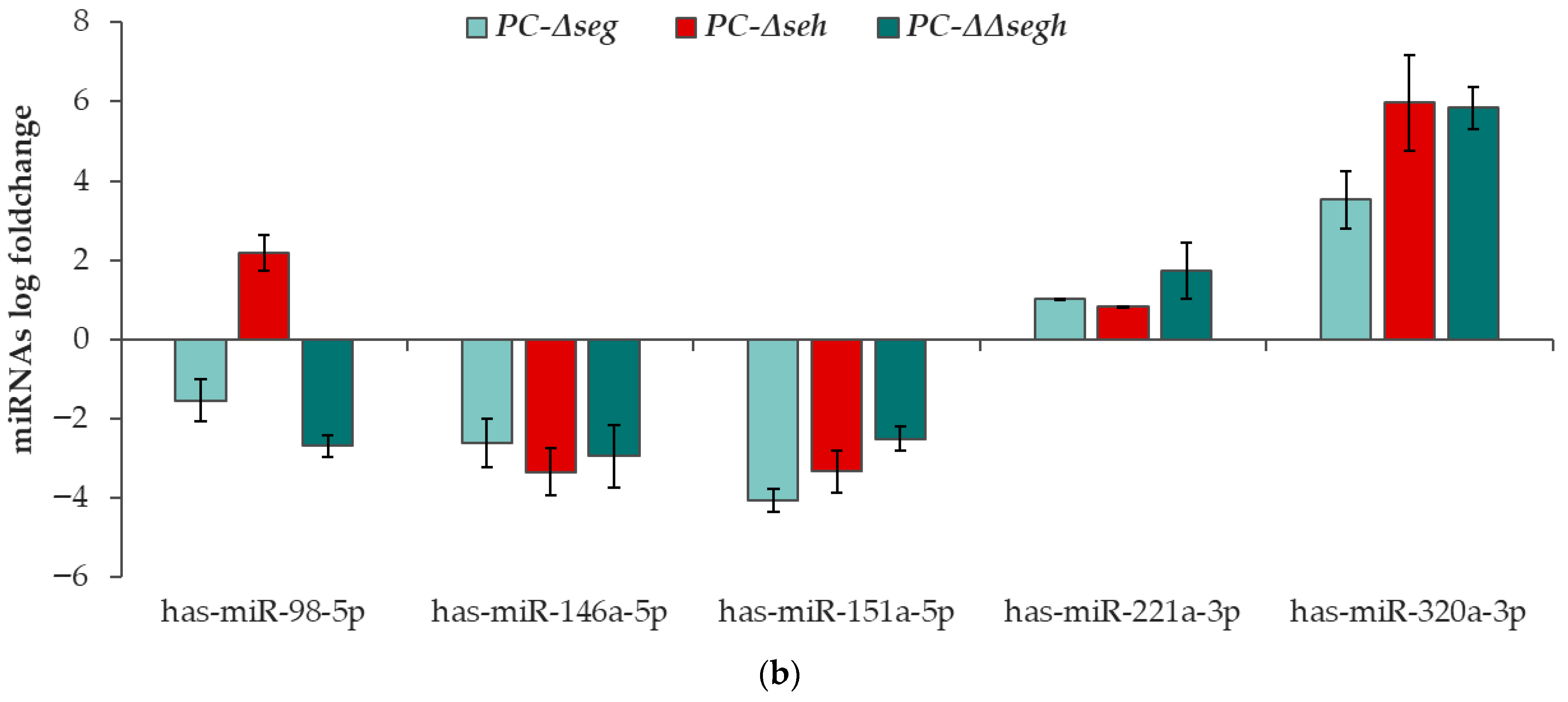

2.3. Platelet microRNA Profile Is Altered by Staphylococcal Enterotoxins During PC Storage

2.4. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Increase Silkworm Mortality

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Staphylococcus aureus Isolates and Inoculation of PCs

5.2. Flow Cytometric Analyses of P-Selectin and Annexin V Expression

5.3. Platelet Cytokine Detection and Quantification

5.4. MicroRNA Next Generation Sequencing and Differential Expression Analysis

5.4.1. Platelet miRNA Extraction from PCs

5.4.2. Small RNA Library Preparation and Sequencing

5.4.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

5.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR of Validation of miRNA Data

5.6. Silkworm Survival Assay

5.7. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CCL2 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 |

| CD62P | Cluster of Differentiation 62P (P-selectin) |

| CXCL9 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 9 |

| ΔΔsegh | Double SEG/SEH-deficient mutant strain |

| Δseg | SEG-deficient mutant strain |

| Δseh | SEH-deficient mutant strain |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| LD50 | Median Lethal Dose |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MIP-3α | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 3 alpha |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B cells |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PC | Platelet Concentrate |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Staphylococcal Enterotoxin |

| SEG | Staphylococcal Enterotoxin G |

| SEH | Staphylococcal Enterotoxin H |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor beta 1 |

| TLR | Toll-like Receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

References

- Chi, S.I.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Platelet concentrates safety: A focus on the challenging pathogen Staphylococcus aureus—A narrative review. Ann. Blood 2025, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza-Correa, M.; Kou, Y.; Taha, M.; Kalab, M.; Ronholm, J.; Schlievert, P.M.; Cahill, M.P.; Skeate, R.; Cserti-Gazdewich, C.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Septic transfusion case caused by a platelet pool with visible clotting due to contamination with Staphylococcus aureus. Transfusion 2017, 57, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.; Pouchol, E.; Sandid, I.; Aoustin, L.; Lefort, C.; Chartois, A.G.; Baima, A.; Malard, L.; Bacquet, C.; Ferrera-Tourenc, V.; et al. Implementation of amotosalen plus ultraviolet A-mediated pathogen reduction for all platelet concentrates in France: Impact on the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections. Vox Sang. 2024, 119, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kozakai, M.; Furuta, R.A.; Matsubayashi, K.; Satake, M. Association of Staphylococcus aureus in platelet concentrates with skin diseases in blood donors: Limitations of cultural bacterial screening. Transfusion 2022, 62, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailsford, S.R.; Tossell, J.; Morrison, R.; McDonald, C.P.; Pitt, T.L. Failure of bacterial screening to detect Staphylococcus aureus: The English experience of donor follow-up. Vox Sang. 2018, 113, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenburg-de, G.W.; Spelmink, S.; Heijnen, J.; de Korte, D. Transfusion transmitted bacterial infections (TTBI) involving contaminated platelet concentrates: Residual risk despite intervention strategies. Ann. Blood 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haass, K.A.; Sapiano, M.R.P.; Savinkina, A.; Kuehnert, M.J.; Basavaraju, S.V. Transfusion-Transmitted Infections Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network Hemovigilance Module. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2019, 33, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfar, H.R.; Whiteheart, S.W. Bacterial interactions with platelets: Defining key themes. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1610289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, A.K.; Birch, K.; Gibbins, J.M.; Clarke, S.R. Activation of Human Platelets by Staphylococcus aureus Secreted Protease Staphopain A. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.R.; Loughman, A.; Keane, F.; Brennan, M.; Knobel, M.; Higgins, J.; Visai, L.; Speziale, P.; Cox, D.; Foster, T.J. Fibronectin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus mediate activation of human platelets via fibrinogen and fibronectin bridges to integrin GPIIb/IIIa and IgG binding to the FcgammaRIIa receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, B.; Pasha, R.; Pineault, N.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Modulation of Staphylococcus aureus gene expression during proliferation in platelet concentrates with focus on virulence and platelet functionality. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Yi, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Feng, P.; Kesheng, D.; Chunyan, H. TSST-1 protein exerts indirect effect on platelet activation and apoptosis. Platelets 2022, 33, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.I.; Kumaran, D.; Zeller, M.P.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Transfusion of a platelet pool contaminated with exotoxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus: A case report. Ann. Blood 2022, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.I.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Enhance Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus aureus in Platelet Concentrates. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.D.; Proft, T. The bacterial superantigen and superantigen-like proteins. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 225, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarraud, S.; Mougel, C.; Thioulouse, J.; Lina, G.; Meugnier, H.; Forey, F.; Nesme, X.; Etienne, J.; Vandenesch, F. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus genetic background, virulence factors, agr groups (alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoe, K.; Imanishi, K.; Hu, D.L.; Kato, H.; Fugane, Y.; Abe, Y.; Hamaoka, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakane, A.; Uchiyama, T.; et al. Characterization of novel staphylococcal enterotoxin-like toxin type P. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 5540–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.I.; Flint, A.; Weedmark, K.; Pagotto, F.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Comparative genome analyses of Staphylococcus aureus from platelet concentrates reveal rearrangements involving loss of type VII secretion genes. Access Microbiol. 2024, 6, 000820.v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, S.I.; Yousuf, B.; Paredes, C.; Bearne, J.; McDonald, C.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Proof of concept for detection of staphylococcal enterotoxins in platelet concentrates as a novel safety mitigation strategy. Vox Sang. 2023, 118, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, J.W.; Italiano, J.E., Jr.; Freedman, J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assinger, A. Platelets and infection—An emerging role of platelets in viral infection. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindayna, K. MicroRNA as Sepsis Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Tang, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C. The MicroRNA network in sepsis: From biomarker discovery to novel targeted therapeutic strategies. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2025, 1–26, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldo, L.; Mena, J.; Serradell, M.; Gaig, C.; Adamuz, D.; Vilas, D.; Samaniego, D.; Ispierto, L.; Montini, A.; Mayà, G.; et al. Platelet miRNAs as early biomarkers for progression of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder to a synucleinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, P.; Plante, I.; Ouellet, D.L.; Perron, M.P.; Rousseau, G.; Provost, P. Existence of a microRNA pathway in anucleate platelets. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhermusier, T.; Chap, H.; Payrastre, B. Platelet membrane phospholipid asymmetry: From the characterization of a scramblase activity to the identification of an essential protein mutated in Scott syndrome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montali, A.; Berini, F.; Brivio, M.F.; Mastore, M.; Saviane, A.; Cappellozza, S.; Marinelli, F.; Tettamanti, G. A Silkworm Infection Model for In Vivo Study of Glycopeptide Antibiotics. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaito, C.; Sekimizu, K. A silkworm model of pathogenic bacterial infection. Drug Discov. Ther. 2007, 1, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Amelirad, A.; Shamsasenjan, K.; Akbarzadehlaleh, P.; Pashoutan, S.D. Signaling Pathways of Receptors Involved in Platelet Activation and Shedding of These Receptors in Stored Platelets. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakauer, T. Update on staphylococcal superantigen-induced signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions. Toxins 2013, 5, 1629–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, A.; Dannenberg, L.; M’Pembele, R.; Mourikis, P.; Naguib, D.; Zako, S.; Helten, C.; Petzold, T.; Levkau, B.; Hohlfeld, T.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus increases platelet reactivity in patients with infective endocarditis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbán-Solano, A.; Flores-Gonzalez, J.; Cruz-Lagunas, A.; Pérez-Rubio, G.; Buendia-Roldan, I.; Ramón-Luing, L.A.; Chavez-Galan, L. High levels of PF4, VEGF-A, and classical monocytes correlate with the platelets count and inflammation during active tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1016472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dai, S.; Qiao, C.; Ye, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Liu, Z. Platelets in infection: Intrinsic roles and functional outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1616783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.O.; Yarwood, L.; Wagstaffe, M.J.; Pepper, D.S.; Macdonald, M.C. Immunomodulatory properties of platelet factor 4: Prevention of concanavalin A suppressor-induction in vitro and augmentation of an antigen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity response in vivo. Immunology 1990, 70, 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, T.B.; Moreira-Nunes, C.d.F.; Maués, J.H.; Lamarão, L.M.; de Lemos, J.A.; Montenegro, R.C.; Burbano, R.M. The miRNA Profile of Platelets Stored in a Blood Bank and Its Relation to Cellular Damage from Storage. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xu, A.; Ai, J.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y. Expression of microRNAs during apheresis platelet storage up to day 14 in a blood bank in China. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2024, 31, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvris, A.; Viñas, J.; Burns, K.D. miRNA-486-5p: Signaling targets and role in non-malignant disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejniczak, M.; Kotowska-Zimmer, A.; Krzyzosiak, W. Stress-induced changes in miRNA biogenesis and functioning. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhong, W.; Zou, Z. miR-98-5p Prevents Hippocampal Neurons from Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis by Targeting STAT3 in Epilepsy in vitro. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Liu, L.; Tang, S.; Zhang, X.; Chang, H.; Chen, W.; Fan, T.; Zhang, L.; Shen, B.; Zhang, Q. MicroRNA-221-3p inhibits the inflammatory response of keratinocytes by regulating the DYRK1A/STAT3 signaling pathway to promote wound healing in diabetes. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, J. The current landscape of microRNAs (miRNAs) in bacterial pneumonia: Opportunities and challenges. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsamaki, A.; Vazgiourakis, V.; Mantzarlis, K.; Stamatiou, R.; Makris, D. MicroRNAs in Sepsis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakos, N.; Gilbert, C.; Théroude, C.; Schrijver, I.T.; Roger, T. Modes of action and diagnostic value of miRNAs in sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 951798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilágyi, B.; Fejes, Z.; Póliska, S.; Pócsi, M.; Czimmerer, Z.; Patsalos, A.; Fenyvesi, F.; Rusznyák, Á.; Nagy, G.; Kerekes, G.; et al. Reduced miR-26b Expression in Megakaryocytes and Platelets Contributes to Elevated Level of Platelet Activation Status in Sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, D.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. The platelet concentrate storage environment may enhance the ability of Cutibacterium acnes to establish chronic infections. Transfusion 2025, 65, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Lu, Z. Immune responses to bacterial and fungal infections in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 83, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewels, P.A.; Peltzer, A.; Nahnsen, S.; Fillinger, S.; Wilm, A.; Patel, H.; Di Tommaso, P.; Alneberg, J.; Garcia, M.U. The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: From microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B. Aligning short sequencing reads with Bowtie. In Current Protocols in Bioinformatics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Chapter 11, Unit-11.7. [Google Scholar]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Ibrahim, J.G.; Love, M.I. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: Removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cytokine Mean (Dot Pixel Range) | Day 0 | Day 2 | Day 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC-Ctrl | PC-SA | PC-Ctrl | PC-SA | PC-Ctrl | PC-SA | |

| IL-8 | 15.83–20.01 | 16.34–25.68 | 18.24–28.66 | 55.45–58.46 | 31.21–45.79 | 81.91–98.29 |

| IL-3 | 2.19–3.09 | 1.75–2.09 | 3.82–4.09 | 7.19–11.4 | 4.86–6.11 | 8.28–12.41 |

| CCL2 | 18.64–19.85 | 19.11–21.80 | 22.01–25.85 | 31.52–34.66 | 26.48–31.36 | 22.22–32.39 |

| EGF | 15.97–20.37 | 13.53–18.81 | 35.22–40.49 | 62.29–69.39 | 53.6–61.53 | 96.59–103.33 |

| MIP-d1 | 31.73–35.11 | 31.38–34.58 | 32.41–38.15 | 58.17–62.53 | 43.96–44.97 | 78.17–84.63 |

| TGF-β1 | 2.30–4.41 | 4.10–4.50 | 8.26–12.89 | 44.4–58.00 | 10.34–14.71 | 34.82–37.75 |

| MIP-3α | 1.97–2.70 | 2.95–3.64 | 4.92–5.87 | 14.52–16.65 | 6.96–11.72 | 20.95–27.41 |

| IFN-γ | 2.53–4.92 | 2.73–3.16 | 6.57–9.81 | 17.35–26.18 | 29.15–39.79 | 40.04–60.40 |

| IGF-1 | 0.82–1.95 | 0.69–1.96 | 7.71–9.63 | 12.75–13.49 | 10.11– 13.71 | 30.7–31.08 |

| TNF-α | 1.91–3.48 | 0.45–1.25 | 1.25–3.96 | 49.78–62.12 | 27.01–35.34 | 62.88–76.85 |

| IL-6 | 1.23–5.24 | 2.61–1.26 | 6.72–8.35 | 10.06–12.85 | 5.98–7.47 | 4.70–6.11 |

| CXCL1 | 2.42–3.89 | 1.54–3.09 | 4.90–6.99 | 8.01–9.83 | 7.04–10.86 | 19.54–22.4 |

| G-CSF | 3.86–4.82 | 1.39–4.20 | 3.86–5.31 | 8.24–11.09 | 6.17–7.82 | 16.25–20.99 |

| CXCL13 | 3.69–4.39 | 1.77–2.03 | 5.10–6.29 | 10.64–12.06 | 6.29–8.23 | 15.29–17.91 |

| OPN | 68.12–74.04 | 82.95–97.41 | 60.47–69.01 | 128.51–137.64 | 156.36–157.52 | 151.69–195.98 |

| S. aureus Strain | PC-WT | PC-Δseg | PC-Δseh | PC-Δsegh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 [CFU/larvae] | ~3.31 × 106 | ~2.31 × 107 | ~3.51 × 107 | ~8.9 × 107 * |

| Silkworm survival from injection with S. aureus-spiked PCs (%) | 27 | 37 | 30 | 40 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chi, S.I.; McGregor, C.; Pineault, N.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Modulate Platelet Response During Storage of Platelet Concentrates and Impair Silkworm Survival. Toxins 2025, 17, 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120593

Chi SI, McGregor C, Pineault N, Ramirez-Arcos S. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Modulate Platelet Response During Storage of Platelet Concentrates and Impair Silkworm Survival. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):593. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120593

Chicago/Turabian StyleChi, Sylvia Ighem, Chelsea McGregor, Nicolas Pineault, and Sandra Ramirez-Arcos. 2025. "Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Modulate Platelet Response During Storage of Platelet Concentrates and Impair Silkworm Survival" Toxins 17, no. 12: 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120593

APA StyleChi, S. I., McGregor, C., Pineault, N., & Ramirez-Arcos, S. (2025). Staphylococcal Enterotoxins Modulate Platelet Response During Storage of Platelet Concentrates and Impair Silkworm Survival. Toxins, 17(12), 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120593