Correlations Between Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, Megalin, Lysine and Markers of Tubular Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

2.2. TMAO, Choline, Betaine, and L-Carnitine Levels in CKD Patients and Healthy Controls

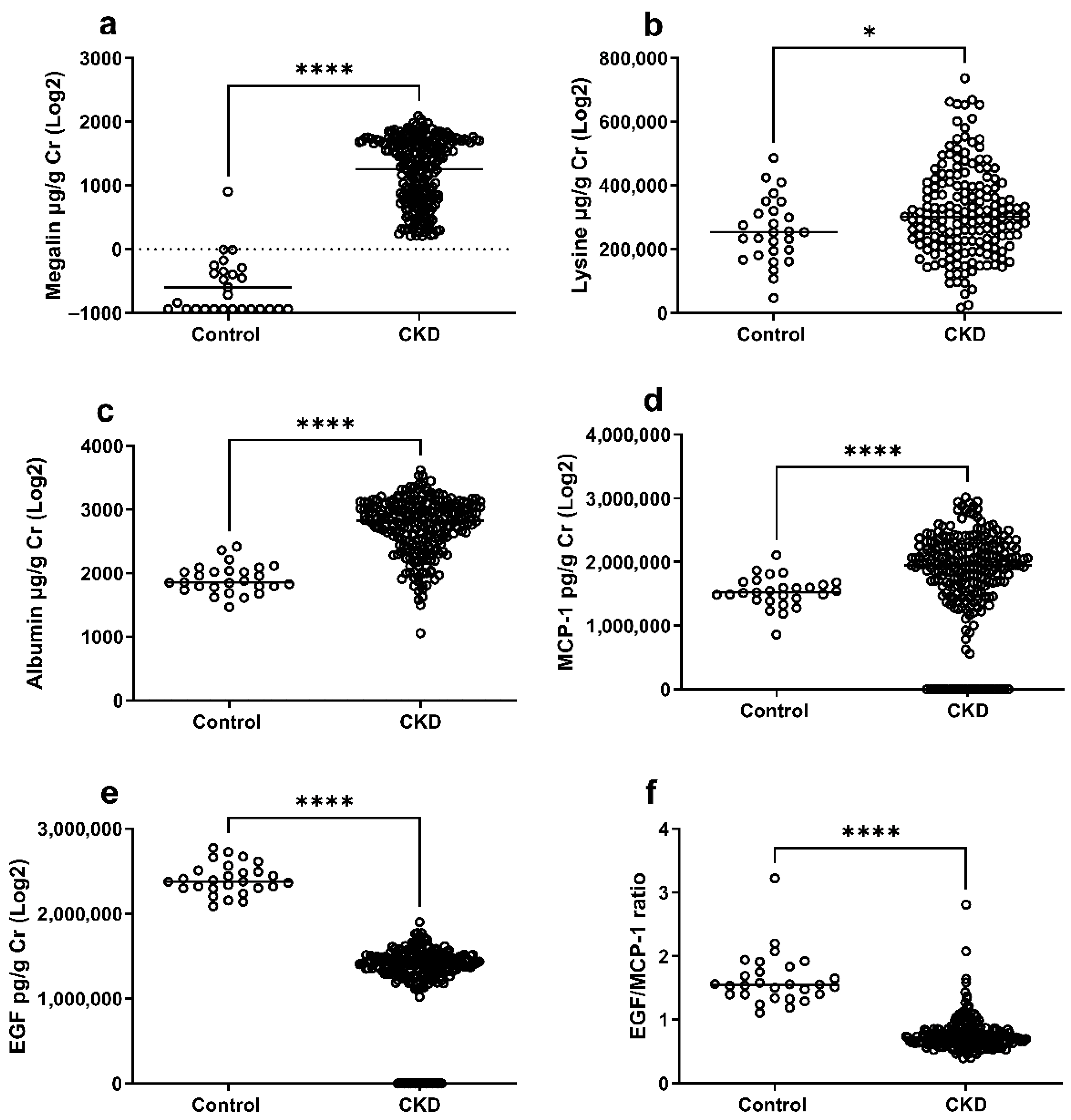

2.3. Soluble Megalin, Lysine, and Markers of Tubular Damage in CKD Patients and Healthy Controls

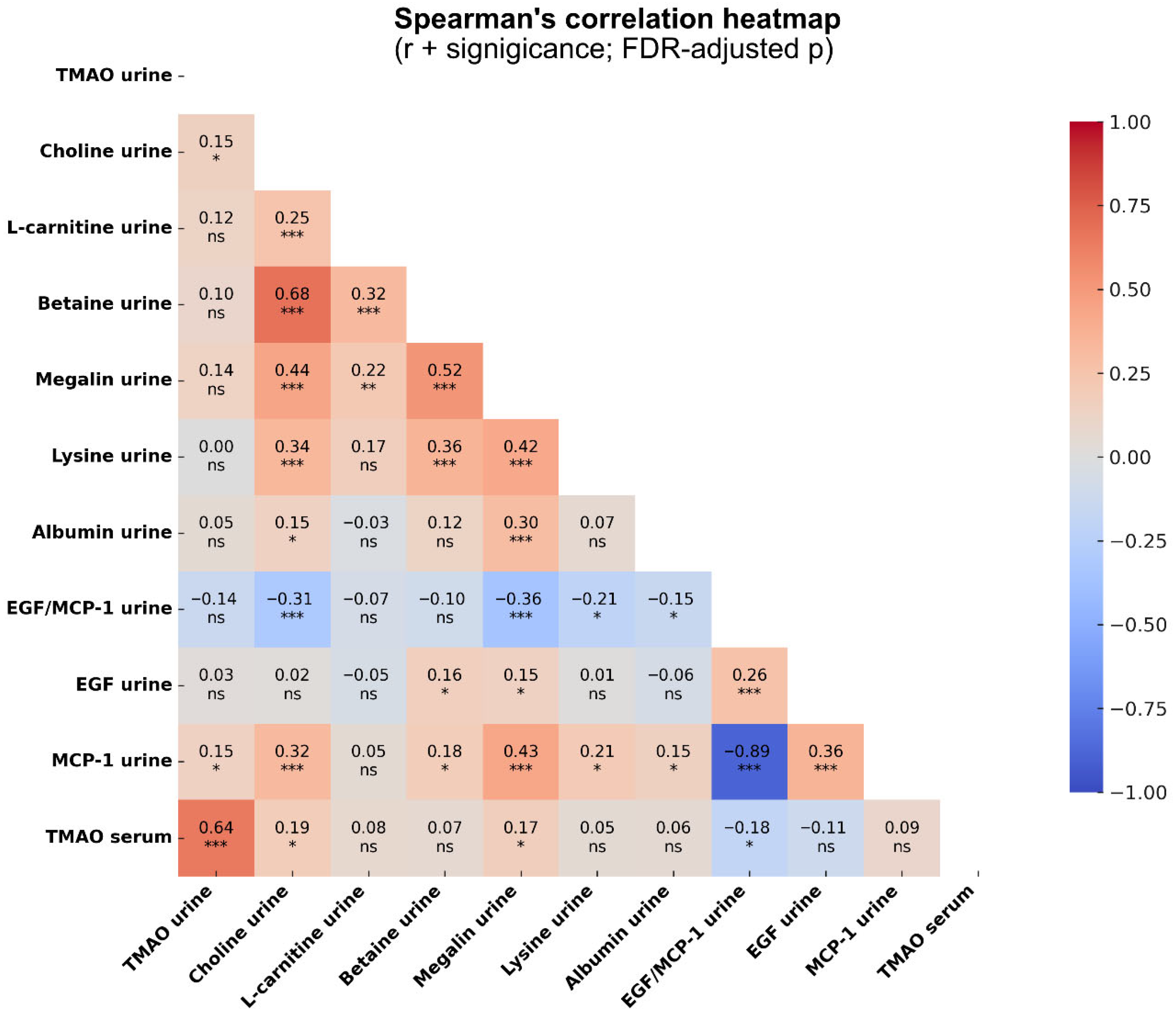

2.4. Correlations Between TMAO, Megalin, Lysine, and Markers of Tubular Damage in CKD

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Patients and Study Design

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Urine Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry

4.4. Measurement of Megalin, Albumin, EGF, and MCP-1 in Urine

4.5. Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, M.; Lewis, R.D.; Morgan, A.R.; Whyte, M.B.; Hanif, W.; Bain, S.C.; Davies, S.; Dashora, U.; Yousef, Z.; Patel, D.C.; et al. A Narrative Review of Chronic Kidney Disease in Clinical Practice: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.R.; Fatoba, S.T.; Oke, J.L.; Hirst, J.A.; O’Callaghan, C.A.; Lasserson, D.S.; Hobbs, F.D.R. Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.N.; Kennedy, D.J.; Wu, Y.P.; Buffa, J.A.; Agatisa-Boyle, B.; Li, X.M.S.; Levison, B.S.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine-Oxide (TMAO) Pathway Contributes to Both Development of Renal Insufficiency and Mortality Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, M.T.; Ramezani, A.; Manal, A.; Raj, D.S. Trimethylamine-Oxide: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Toxins 2016, 8, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.N.; Du, J.P.; Chen, Z.H.; Shi, D.Z.; Qu, H. Effects of Microbiota-Driven Therapy on Circulating Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Metabolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 710567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.L.; Savoj, J.; Nakata, M.B.; Vaziri, N.D. Altered microbiome in chronic kidney disease: Systemic effects of gut-derived uremic toxins. Clin. Sci. 2018, 132, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.C.; Croyal, M.; Ene, L.; Aguesse, A.; Billon-Crossouard, S.; Krempf, M.; Lemoine, S.; Guebre-Egziabher, F.; Juillard, L.; Soulage, C.O. Elevation of Trimethylamine-N-Oxide in Chronic Kidney Disease: Contribution of Decreased Glomerular Filtration Rate. Toxins 2019, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruppen, E.G.; Garcia, E.; Connelly, M.A.; Jeyarajah, E.J.; Otvos, J.D.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Dullaart, R.P.F. TMAO is Associated with Mortality: Impact of Modestly Impaired Renal Function. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.B.; Morse, B.L.; Djurdjev, O.; Tang, M.L.; Muirhead, N.; Barrett, B.; Holmes, D.T.; Madore, F.; Clase, C.M.; Rigatto, C.; et al. Advanced chronic kidney disease populations have elevated trimethylamine N-oxide levels associated with increased cardiovascular events. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, J.A.P.; Wheeler, D.C. The role of trimethylamine N-oxide as a mediator of cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, J.R.; House, J.A.; Ocque, A.J.; Zhang, S.Q.; Johnson, C.; Kimber, C.; Schmidt, K.; Gupta, A.; Wetmore, J.B.; Nolin, T.D.; et al. Serum Trimethylamine--Oxide is Elevated in CKD and Correlates with Coronary Atherosclerosis Burden. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, W.H.W.; Li, X.M.S.; Otto, M.C.D.; Lemaitre, R.; Fretts, A.M.; Nemet, I.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Budoff, M.J.; Didonato, J.A.; et al. Associations of Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide-Related Metabolites with the Development and Progression of Albuminuria. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, W.H.W.; Li, X.S.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Lee, Y.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Fretts, A.; Nemet, I.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Sitlani, C.M.; et al. The Gut Microbial Metabolite Trimethylamine N -oxide, Incident CKD, and Kidney Function Decline. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 35, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkins, K.S.; Schnaper, H.W. Tubulointerstitial injury and the progression of chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2012, 27, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, S.; Hosojima, M.; Kaseda, R.; Kabasawa, H.; Yamamoto-Kabasawa, K.; Kurosawa, H.; Sato, H.; Iino, N.; Takeda, T.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Significance of Urinary Full-Length and Ectodomain Forms of Megalin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.; Maxwell, A.P.; Brazil, D.P. The Potential of Albuminuria as a Biomarker of Diabetic Complications. Cardiovasc. Drug Ther. 2021, 35, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, R.; Christensen, E.I.; Birn, H. Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption: From experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansevoort, R.T.; de Jong, P.E. The Case for Using Albuminuria in Staging Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, H.; Niihata, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Fujimura, M.; Kurosawa, K.; Sakuramachi, Y.; Takano, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Okamura, S.; Kitatani, M.; et al. Urinary C-megalin as a novel biomarker of progression to microalbuminuria: A cohort study based on the diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 22). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 186, 109810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanaki, S.; Kumawat, A.K.; Persson, K.; Demirel, I. TMAO Suppresses Megalin Expression and Albumin Uptake in Human Proximal Tubular Cells Via PI3K and ERK Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wysocki, J.; Ye, M.H.; Vallés, P.G.; Rein, J.; Shirazi, M.; Bader, M.; Gomez, R.A.; Sequeira-Lopez, M.L.S.; Afkarian, M.; et al. Urinary Renin in Patients and Mice With Diabetic Kidney Disease. Hypertension 2019, 74, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Martini, A.G.; Janssen, M.J.; Garrelds, I.M.; Masereeuw, R.; Lu, X.F.; Danser, A.H.J. Megalin A Novel Endocytic Receptor for Prorenin and Renin. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thelle, K.; Christensen, E.; Vorum, H.; Orskov, H.; Birn, H. Characterization of proteinuria and tubular protein uptake in a new model of oral L-lysine administration in rats. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinschen, M.M.; Palygin, O.; El-Meanawy, A.; Domingo-Almenara, X.; Palermo, A.; Dissanayake, L.V.; Golosova, D.; Schafroth, M.A.; Guijas, C.; Demir, F.; et al. Accelerated lysine metabolism conveys kidney protection in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Massy, Z.A.; Stenvinkel, P.; Chesnaye, N.C.; Larabi, I.A.; Alvarez, J.C.; Caskey, F.J.; Torino, C.; Porto, G.; Szymczak, M.; et al. The association between TMAO, CMPF, and clinical outcomes in advanced chronic kidney disease: Results from the European QUALity (EQUAL) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J.; Kang, M.S.; Song, J.; Kim, S.G.; Cho, S.; Huh, H.; Lee, S.; Park, S.; Jo, H.A.; et al. Urinary Metabolite Profile Predicting the Progression of CKD. Kidney360 2023, 4, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanaki, S.; Kumawat, A.K.; Persson, K.; Demirel, I. The Fibrotic Effects of TMAO on Human Renal Fibroblasts Is Mediated by NLRP3, Caspase-1 and the PERK/Akt/mTOR Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefania, K.; Ashok, K.K.; Geena, P.V.; Katarina, P.; Isak, D. TMAO enhances TNF-alpha mediated fibrosis and release of inflammatory mediators from renal fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missailidis, C.; Hallqvist, J.; Qureshi, A.R.; Barany, P.; Heimburger, O.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P.; Bergman, P. Serum Trimethylamine--Oxide Is Strongly Related to Renal Function and Predicts Outcome in Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0141738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouque, D.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kopple, J.; Cano, N.; Chauveau, P.; Cuppari, L.; Franch, H.; Guarnieri, G.; Ikizler, T.A.; Kaysen, G.; et al. A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, T.; Hosojima, M.; Kabasawa, H.; Yamamoto-Kabasawa, K.; Goto, S.; Tanaka, T.; Kitamura, N.; Nakada, M.; Itoh, S.; Ogasawara, S.; et al. Urinary A- and C-megalin predict progression of diabetic kidney disease: An exploratory retrospective cohort study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2022, 36, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, A.; Terryn, S.; Schmidt, V.; Christensen, E.I.; Huska, M.R.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Hubner, N.; Devuyst, O.; Hammes, A.; Willnow, T.E. The soluble intracellular domain of megalin does not affect renal proximal tubular function in vivo. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, S.; Kuwahara, S.; Hosojima, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Kaseda, R.; Sarkar, P.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kabasawa, H.; Iida, T.; Goto, S.; et al. Exocytosis-Mediated Urinary Full-Length Megalin Excretion Is Linked With the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauta, F.L.; Boertien, W.E.; Bakker, S.J.L.; van Goor, H.; van Oeveren, W.; de Jong, P.E.; Bilo, H.; Gansevoort, R.T. Glomerular and Tubular Damage Markers Are Elevated in Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, Y. Epidermal growth factor as a prognostic biomarker in chronic kidney diseases. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satirapoj, B.; Dispan, R.; Radinahamed, P.; Kitiyakara, C. Urinary epidermal growth factor, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 or their ratio as predictors for rapid loss of renal function in type 2 diabetic patients with diabetic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesch, G.H.; Schwarting, A.; Kinoshita, K.; Lan, H.Y.; Rollins, B.J.; Kelley, V.R. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promotes macrophage-mediated tubular injury, but not glomerular injury, in nephrotoxic serum nephritis. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harskamp, L.R.; Meijer, E.; van Goor, H.; Engels, G.E.; Gansevoort, R.T. Stability of tubular damage markers epidermal growth factor and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in urine. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2019, 57, e265–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, M.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, L.; Nie, J. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Aggravates Kidney Injury via Activation of p38/MAPK Signaling and Upregulation of HuR. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2022, 47, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanish, M.K.; Chapman, A.N.; Yates, S.; Price, R.; Hendry, B.M.; Roderick, P.J.; Dockrell, M.E.C. Evaluation of Urinary Biomarkers of Proximal Tubular Injury, Inflammation, and Fibrosis in Patients With Albuminuric and Nonalbuminuric Diabetic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, L.; Ferreira, M.S.; Kemp, J.A.; Mafra, D. The Role of Betaine in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, R.B.; Ortiz, A.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Markoska, K.; Schepers, E.; Vanholder, R.; Glorieux, G.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Heinzmann, S.S. Increased urinary osmolyte excretion indicates chronic kidney disease severity and progression rate. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2018, 33, 2156–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Liu, S.; Gurung, R.L.; Lee, J.; Zheng, H.L.; Ang, K.; Chan, C.; Lee, L.S.; Han, S.R.; Kovalik, J.P.; et al. Urine Choline Oxidation Metabolites Predict Chronic Kidney Disease Progression in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2025, dgaf281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leschke, M.; Rumpf, K.W.; Eisenhauer, T.; Becker, K.; Bock, U.; Scheler, F. Serum levels and urine excretion of L-carnitine in patients with normal and impaired kidney function. Klin. Wochenschr. 1984, 62, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, J.; Ito, S.; Kodama, G.; Nakayama, Y.; Kaida, Y.; Yokota, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Tashiro, K.; Fukami, K. Kinetics of Serum Carnitine Fractions in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Not on Dialysis. Kurume Med. J. 2021, 66, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Buffa, J.A.; Roberts, A.B.; Sangwan, N.; Skye, S.M.; Li, L.; Ho, K.J.; Varga, J.; DiDonato, J.A.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. Targeted Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine N-Oxide Production Reduces Renal Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis and Functional Impairment in a Murine Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Arter. Throm Vas. 2020, 40, 1239–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, K.J.; Ocak, G.; Drechsler, C.; Caskey, F.J.; Evans, M.; Postorino, M.; Dekker, F.W.; Wanner, C. The EQUAL study: A European study in chronic kidney disease stage 4 patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2012, 27, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Controls (n = 27) | CKD 4–5 (n = 233) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 70 ± 5 | 75 ± 6 | 0.0002 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 22 (81) | 160 (69) | 0.191 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 ± 3.1 | 27.6 ± 5 | 0.032 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 7 (26) | 16 (7) | 0.0046 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 2 (1) | 88 (38) | 0.0011 |

| CVD, n (%) | 2 (1) | 38 (16) | 0.395 |

| eGFR MDRD | 77 (72–95) | 20 (17–23) | 0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | NA | 76 (70–85) | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | NA | 148 (133–161) | |

| SGA overall assessment | 7 (7–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.0001 |

| SGA < 5 (malnourished), n (%) | 0 (0) | 27 (12) | 0.0888 |

| α-Blocker, n (%) | NA | 4 (1.7) | |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | NA | 69 (30) | |

| ACEi/ARB, n (%) | NA | 96 (41.4) | |

| Lipid-lowering, n (%) | NA | 78 (33.6) | |

| Diuretic, n (%) | NA | 106 (45.7) | |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 83 (70–91) | 271 (225–311) | 0.0001 |

| Albumin, g/L | 38 (36–41) | 36 (33–38) | 0.0011 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) | 2.28 (2.19–2.37) | 0.82 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1 (0.9–1.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 144 (133–149) | 118 (108–127) | 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.7 (4.1–5.8) | 4.6 (3.8–5.5) | 0.024 |

| CKD vs. Control β (95% CI); FDR | Age Effect β (95% CI); FDR | Diabetes Effect β (95% CI); FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMAO urine | 807 (−1.46 × 105 to 1.48 × 105); FDR = 0.991 | −4.1 × 103 (−1.09 × 104 to 2.71 × 103); p = 0.237 | 2.3 × 104 (−6.91 × 104 to 1.15 × 105); p = 0.624 |

| Choline urine | 1.5 × 105 (8.07 × 104 to 2.2 × 105); FDR < 0.001 | −3.95 × 103 (−7.17 × 103 to −731); p = 0.016 | 6.71 × 104 (2.35 × 104 to 1.11 × 105); p = 0.0026 |

| L-carnitine urine | −1.02 × 105 (−1.65 × 105 to −3.98 × 104); FDR = 0.0024 | −2.55 × 103 (−5.44 × 103 to 332); p = 0.0826 | 2.44 × 104 (−1.47 × 104 to 6.34 × 104); p = 0.22 |

| Betaine urine | 8.75 × 104 (2.61 × 104 to 1.49 × 105); FDR = 0.0067 | −2.69 × 103 (−5.52 × 103 to 149); p = 0.0632 | 2.74 × 104 (−1.1 × 104 to 6.58 × 104); p = 0.161 |

| Megalin urine | 1.92 × 103 (1.71 × 103 to 2.14 × 103); FDR < 0.001 | −10.4 (−20.4 to −0.466); p = 0.040 | −51.7 (−186 to 82.9); p = 0.45 |

| Lysine urine | 8.81 × 104 (2.73 × 104 to 1.49 × 105); FDR = 0.0047 | −3.16 × 103 (−5.97 × 103 to −347); p = 0.0278 | 2.53 × 104 (−1.27 × 104 to 6.33 × 104); p = 0.191 |

| MCP-1 urine | 2.58 × 105 (−3.32 × 104 to 5.5 × 105); FDR = 0.0914 | −2.14 × 103 (−1.56 × 104 to 1.13 × 104); p = 0.754 | 2.45 × 104 (−1.58 × 105 to 2.07 × 105); p = 0.791 |

| EGF urine | −1.10 × 106 (−1.27 × 106 to −9.26 × 105); FDR < 0.001 | 1.83 × 103 (−6.19 × 103 to 9.85 × 103); p = 0.654 | −8.36 × 104 (−1.92 × 105 to 2.49 × 104); p = 0.13 |

| EGF/MCP-1 | −0.902 (−1.05 to −0.758); FDR < 0.001 | −2.54 × 10−5 (−0.00667 to 0.00662); p = 0.994 | −0.11 (−0.199 to −0.0196); p = 0.017 |

| Albumin | 844 (667 to 1.02 × 103); FDR < 0.001 | −4.21 (−12.4 to 3.98); p = 0.312 | 28.9 (−81.9 to 140); p = 0.608 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kapetanaki, S.; Salihovic, S.; Kumawat, A.K.; Massy, Z.A.; Persson, K.; Barany, P.; Stenvinkel, P.; Evans, M.; Demirel, I. Correlations Between Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, Megalin, Lysine and Markers of Tubular Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins 2025, 17, 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120592

Kapetanaki S, Salihovic S, Kumawat AK, Massy ZA, Persson K, Barany P, Stenvinkel P, Evans M, Demirel I. Correlations Between Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, Megalin, Lysine and Markers of Tubular Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):592. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120592

Chicago/Turabian StyleKapetanaki, Stefania, Samira Salihovic, Ashok Kumar Kumawat, Ziad A. Massy, Katarina Persson, Peter Barany, Peter Stenvinkel, Marie Evans, and Isak Demirel. 2025. "Correlations Between Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, Megalin, Lysine and Markers of Tubular Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease" Toxins 17, no. 12: 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120592

APA StyleKapetanaki, S., Salihovic, S., Kumawat, A. K., Massy, Z. A., Persson, K., Barany, P., Stenvinkel, P., Evans, M., & Demirel, I. (2025). Correlations Between Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, Megalin, Lysine and Markers of Tubular Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins, 17(12), 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120592