Natural Occurrence of Conventional and Emerging Fusarium Mycotoxins in Freshly Harvested Wheat Samples in Xinjiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Natural Occurrence of Fusarium Mycotoxins

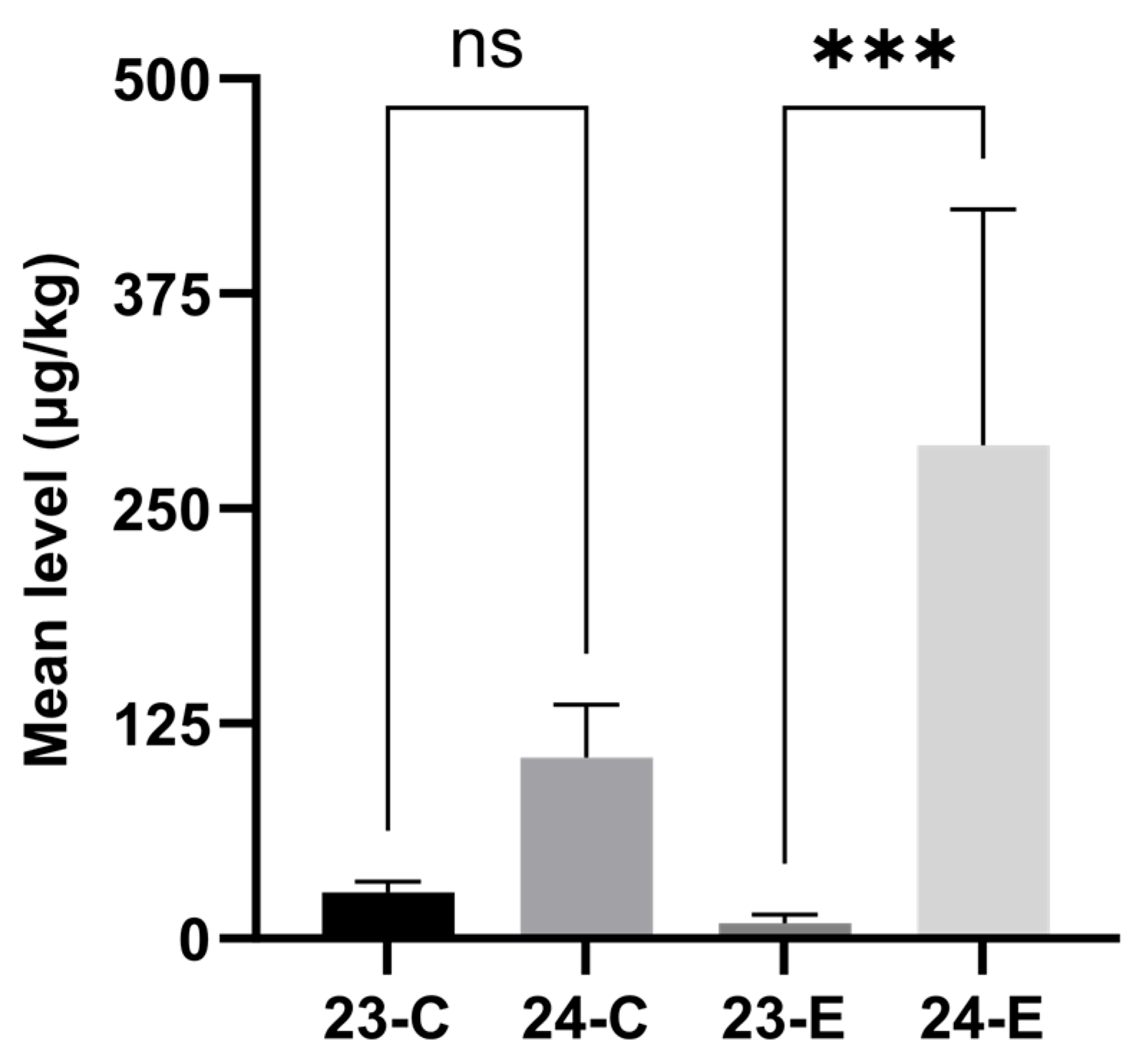

2.2. Effect of Sampling Timing and Regions on the Contents of Mycotoxins

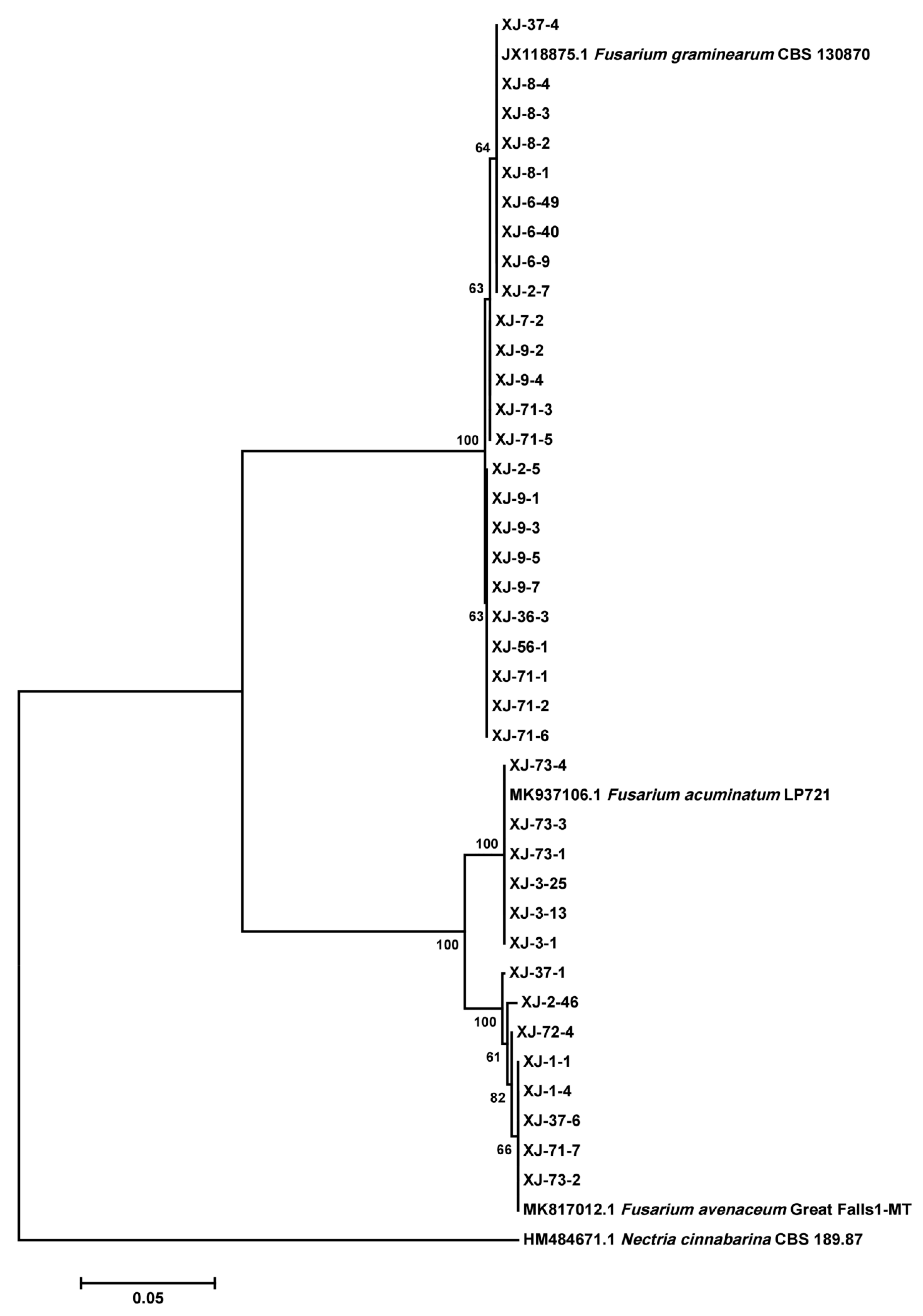

2.3. Species Composition and Chemotype of Fusarium Isolates

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

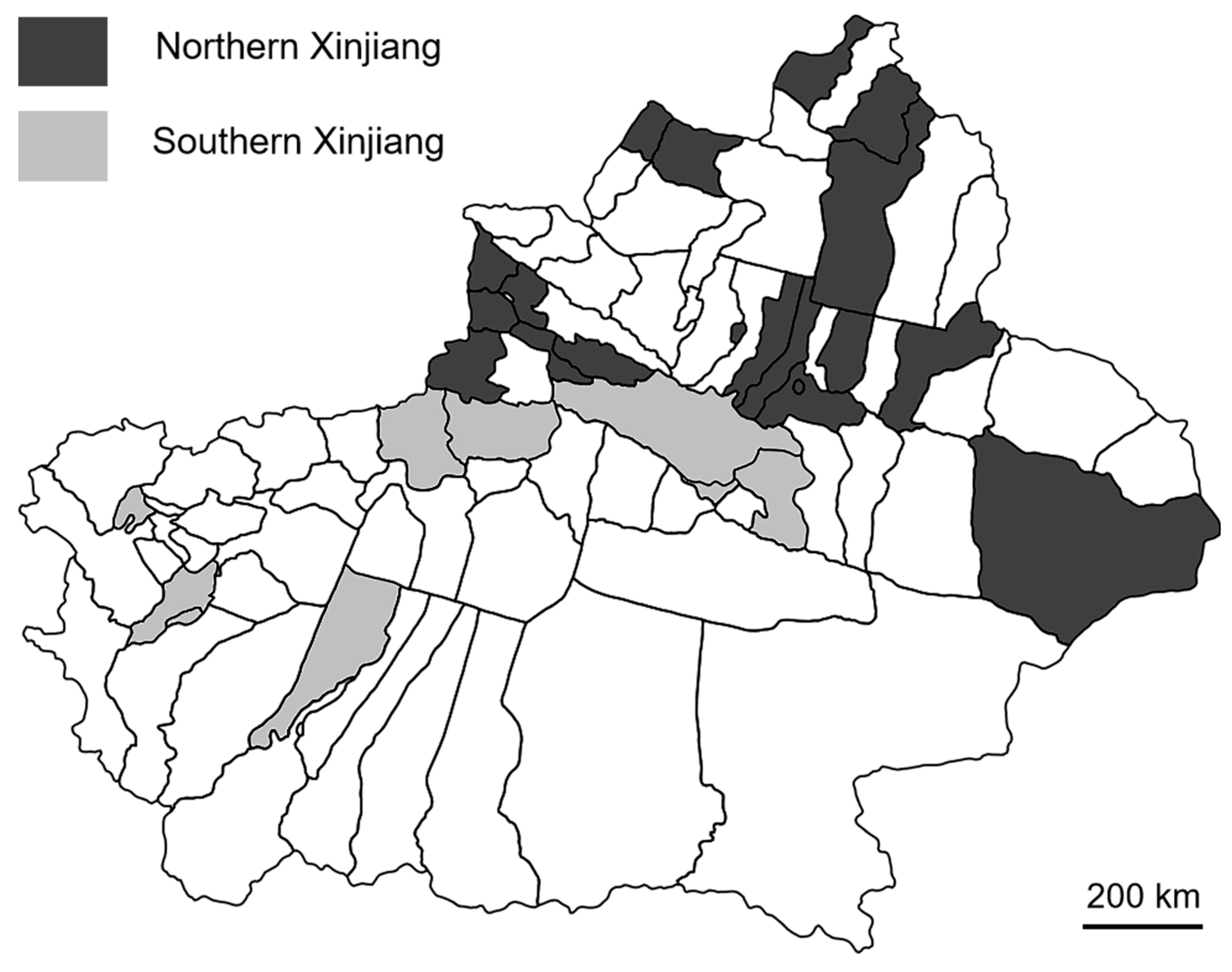

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. Mycotoxin Analysis and Method Validation

4.4. Fungi Isolation

4.5. Species Composition of Fusarium Isolates

4.6. Genotype and Mycotoxin Production of Fusarium Isolates

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, H.; Ding, Y.D.; Fan, G.Q.; Gao, Y.H.; Huang, T.R. Research report on the development status of wheat industry in southern Xinjiang. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2024, 61, 5–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.B.; Xu, J.H.; Shi, J.R. Fusarium toxins in Chinese wheat since the 1980s. Toxins 2019, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Guan, X.L.; Zong, Y.; Hua, X.T.; Xing, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.Z.; Liu, Y. Deoxynivalenol in wheat from the Northwestern region in China. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2018, 11, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.L.; Wang, M.M.; Ma, Z.Y.; Raze, M.; Zhao, P.; Liang, J.M.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, J.W.; Hu, D.M.; et al. Fusarium diversity associated with diseased cereals in China, with an updated phylogenomic assessment of the genus. Stud. Mycol. 2023, 104, 87–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.M.; Crous, P.W.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Han, S.L.; Liu, F.; Liang, J.M.; Duan, W.J.; Cai, L. Fusarium and allied genera from China: Species diversity and distribution. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2022, 48, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, W.; Deng, F.F.; Niu, W.L.; Shen, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.K.; Gao, H.F. Occurrence of Fusarium crown rot caused by Fusarium culmorum on winter wheat in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.L.; Walkowiak, S.; Sura, S.; Ojo, E.R.; Henriquez, M.A. Genomics and transcriptomics of 3ANX (NX-2) and NX (NX-3) producing isolates of Fusarium graminearum. Toxins 2025, 17, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakroun, Y.; Oueslati, S.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Abderrabba, M.; Savoie, J.M. Characterization of Fusarium acuminatum: A potential enniatins producer in Tunisian wheat. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, M.T.; Ward, T.J.; Cappelletti, E.; Beccari, G.; McCormick, S.P.; Busman, M.; Laraba, I.; O’Donnell, K.; Prodi, A. Species diversity and mycotoxin production by members of the Fusarium tricinctum species complex associated with Fusarium head blight of wheat and barley in Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 358, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.Y.; Zhang, T.W.; Xing, Y.J.; Dai, C.C.; Ciren, D.J.; Yang, X.J.; Wu, X.L.; Mokoena, M.P.; Olaniran, A.O.; Shi, J.R.; et al. Characterization of Fusarium species causing head blight of highland barley (qingke) in Tibet, China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 418, 110728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, M.; Waśkiewica, A.; Stępień, Ł. Fusarium cyclodepsipeptide mycotoxins: Chemistry, biosynthesis, and occurrence. Toxins 2020, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.M.; Xu, E.J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Li, F.Q. Natural occurrence of beauvericin and enniatins in corn- and wheat-based samples harvested in 2017 collected from Shandong Province, China. Toxins 2018, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.F.; Jin, C.H.; Xiao, Y.P.; Deng, M.H.; Wang, W.; Lyu, W.T.; Chen, J.P.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, H. Natural occurrence of regulated and emerging mycotoxins in wheat grains and assessment of the risks from dietary mycotoxins exposure in China. Toxins 2023, 15, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Y.J.; Zhang, D.W.; Liu, Z.N.; Sun, X.Y.; Yang, X.T. Occurrence of regulated, emerging, and masked mycotoxins in Chinese wheat between 2021 and 2022. Toxicon 2025, 260, 108344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.L.; Qiu, N.N.; Zhou, S.; Lyu, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.G.; Zhao, Y.F.; Wu, Y.N. Development of sensitive and reliable UPLC-MS/MS methods for food analysis of emerging mycotoxins in China total diet study. Toxins 2019, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Sui, H.X.; Ye, J.; Wu, Y.; et al. Natural occurrence and co-occurrence of beauvericin and enniatins in wheat kernels from China. Toxins 2024, 16, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 2761-2017; National Food Safety Standard Limit of Mycotoxins in Foods. Standardization administration of the people’s republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/1756 of 25 June 2024 amending and correcting Regulation (EU) 2023/915 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/1022 of 8 April 2024 amending Regulation (EU) 2023/915 as regards maximum levels of deoxynivalenol in food. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, 4.9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.Y.; Zhang, T.W.; Dai, C.C.; He, C.; Ciren, D.J.; Shi, J.R.; Xing, Y.J.; Xu, J.H.; Li, Y.; Dong, F. Determination and contamination of mycotoxins in highland barley grain samples from Xizang. J. Chin. Cereals Oils Assoc. 2024, 39, 189–195. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.W.; Wu, D.L.; Li, W.D.; Hao, Z.H.; Wu, X.L.; Xing, Y.J.; Shi, J.R.; Li, Y.; Dong, F. Occurrence of Fusarium mycotoxins in freshly harvested highland barley (qingke) grains from Tibet, China. Mycotoxin Res. 2023, 39, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, I.; Persson, P.; Friberg, H. Fusarium head blight from a microbiome perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 628373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulet, F.; Hymery, N.; Coton, E.; Coton, M. Enniatin mycotoxins in food: A systematic review of global occurrence, biosynthesis, and toxicological impacts on in vitro human cell models. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz, C.; Saladino, F.; Luciano, F.B.; Mañes, J.; Meca, G. Occurrence, toxicity, bioaccessibility and mitigation strategies of beauvericin, a minor Fusarium mycotoxin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, H.J.; Pringas, C.; Maerlaender, B. Evaluation of environmental and management effects on Fusarium head blight infection and deoxynivalenol concentration in the grain of winter wheat. Eur. J. Agron. 2006, 24, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.B.; Dong, F.; Yu, M.; Xu, J.H.; Shi, J.R. Effect of preceding crop on Fusarium species and mycotoxin contamination of wheat grains. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4536–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.F.; Yao, J.Q.; Zhang, W.N. Spatiotemporal precipitation variation in Xinjiang from 1961 to 2018. J. Wuyi Univ. 2021, 40, 45–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.; Qiu, J.B.; Xu, J.H.; Yu, M.Z.; Wang, S.F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, G.F.; Shi, J.R. Effect of environmental factors on Fusarium population and associated trichothecenes in wheat grain grown in Jiangsu province, China. Int. J. Food microbiol. 2016, 230, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M.L.; Chulze, S.; Magan, N. Temperature and water activity effects on growth and temporal deoxynivalenol production by two Argentinean strains of Fusarium graminearum on irradiated wheat grain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizán, M.M.; Gomez, A.D.L.A.; Baptista, Z.P.T.; Jimenez, C.M.; Matías, M.D.H.S.; Catalán, C.A.; Sampietro, D.A. Influence of water activity and temperature on growth and production of trichothecenes by Fusarium graminearum sensu stricto and related species in maize grains. Sampietro, D.A. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 305, 108242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Albuquerque, D.; Patriarca, A.; Fernández Pinto, V. Water activity influence on the simultaneous production of DON, 3-ADON and 15-ADON by a strain of Fusarium graminearum sensu stricto of 15-ADON genotype. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 373, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybecky, A.I.; Chulze, S.N.; Chiotta, M.L. Effect of water activity and temperature on growth and trichothecene production by Fusarium graminearum on maize grains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 285, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Chen, X.X.; Lei, X.Y.; Wu, D.L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Lee, Y.-W.; Mokoena, M.P.; Olaniran, A.O.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Effect of crop rotation on Fusarium mycotoxins and Fusarium species in cereals in Sichuan Province (China). Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, Z.Q.; Chen, S.B.; Duan, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.D.; Wang, T.; Guo, B.; Li, Y.M. Comparing utilization of solar, heat sesources and yield production with summer and multiple cropping silage corn in the northern Xinjiang. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 26, 63–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dill-Macky, R.; Jones, R.K. The effect of previous crop residues and tillage on Fusarium head blight of wheat. Plant Dis. 2000, 84, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorano, A.; Blandino, M.; Reyneri, A.; Vanara, F. Effect of maize residues on the Fusarium spp. infection and deoxynivalenol (DON) contamination of wheat grain. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, J.N.; Zhao, Y.; Sangare, L.; Xing, F.G.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Xue, X.F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Limited survey of deoxynivalenol in wheat from different crop rotation fields in Yangtze-Huaihe river basin region of China. Food Control 2015, 53, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y.; Gao, S.M.; Liu, S.J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.F. Analysis on the species composition and mycotoxin chemotypes of wheat Fusarium head blight in Shandong Province. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2017, 32, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.M.; Hu, Y.C.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, W.; Guo, J.H.; Chen, H.G. Geographic distribution of trichothecene chemotypes of the Fusarium graminearum species complex in major winter wheat production areas of China. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Liu, J.W.; Liu, B.J.; Liu, B.; Liang, Y.C. Composition and pathogenicity differentiation of pathogenic species isolated from Fusarium head blight in Shandong Province. J. Plant Prot. 2013, 40, 27–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lee, T.; Zhang, H.; Van Diepeningen, A.D.; Waalwijk, C. Biogeography of Fusarium graminearum species complex and chemotypes: A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2015, 32, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.X.; Zhang, H.; Kong, X.J.; Van der Lee, T.; Waalwijk, C.; Van Diepeningen, A.D.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.S.; Chen, W.Q.; Feng, J. Host and cropping system shape the Fusarium population: 3ADON-producers are ubiquitous in wheat whereas NIV-producers are more prevalent in rice. Toxins 2018, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, R.L.; Higgens, C.E.; Boaz, H.E.; Gorman, M. The structure of beauvericin, a new depsipeptide antibiotic toxic to Artemia salina. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 49, 4255–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, Ł.; Waśkiewicz, A. Sequence divergence of the enniatin synthase gene in relation to production of beauvericin and enniatins in Fusarium species. Toxins 2013, 5, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.; Singh, S.K.; Dufossé, L. Multigene phylogeny, beauvericin production and bioactive potential of Fusarium strains isolated in India. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liuzzi, V.C.; Mirabelli, V.; Cimmarusti, M.T.; Haidukowski, M.; Leslie, J.F.; Logrieco, A.F.; Caliandro, R.; Fanelli, F.; Mulè, G. Enniatin and beauvericin biosynthesis in Fusarium species: Production profiles and structural determinant prediction. Toxins 2017, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, T.; Pszczółkowska, K.; Fordoński, G.; Olszewski, J. PCR approach based on the esyn1 gene for the detection of potential enniatin-producing Fusarium species. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 117, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarelli, L.; Beccari, G.; Prodi, A.; Generotti, S.; Etruschi, F.; Meca, G.; Juan, C.; Mañes, J. Biosynthesis of beauvericin and enniatins in vitro by wheat Fusarium species and natural grain contamination in an area of central Italy. Food Microbiol. 2015, 46, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, D.; Gong, Y.Y.; Routledge, M.N.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y. Risk assessment of deoxynivalenol in high-risk area of China by human biomonitoring using an improved high-throughput UPLC-MS/MS method. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, R.H.; Tong, E.Y.; Wu, P.G.; Chen, J.; Zhao, D.; Pan, X.D.; Wang, J.K.; Wu, X.L.; Zhang, H.X.; et al. Occurrence and exposure assessment of deoxynivalenol and its acetylated derivatives from grains and grain products in Zhejiang Province, China (2017–2020). Toxins 2022, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific Opinion on the risks to human and animal health related to the presence of beauvericin and enniatins in food and feed. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3802.

- European Commission. Commission regulation (EC) No. 401/2006 of 23 February 2006, laying down the methods of sampling and analysis for the official control of the levels of mycotoxins in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2006, 70, 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; Blackwell Publishing: Ames, IA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhang, J.B.; Chen, F.F.; Li, H.P.; Ndoye, M.; Liao, Y.C. A multiplex PCR assay for genetic chemotyping of toxigenic Fusarium graminearum and wheat grains for 3-acetyldeoxynivalenol, 15-acetyldeoxynivalenol and nivalenol mycotoxins. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

| Mycotoxin | Positive Samples (n) a | Incidence of Contamination (%) | Mean of Positive Samples (μg/kg) | Contamination Range (μg/kg) | ML (μg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | EU | |||||

| ZEN | 62 | 41.1 | 9.67 ± 1.04 | 0.96–45.5 | 60 | 100 |

| DON | 47 | 31.1 | 170 ± 23.1 | 10.3–831 | 1000 | 1500 |

| ENNB | 28 | 18.5 | 319 ± 62.8 | 5.60–3305 | / | / |

| BEA | 22 | 14.6 | 115 ± 16.1 | 6.35–829 | / | / |

| ENNB1 | 13 | 8.61 | 565 ± 97.2 | 7.03–3832 | / | / |

| ENNA1 | 9 | 5.96 | 341 ± 51.0 | 12.5–1651 | / | / |

| 3ADON | 7 | 4.64 | 130 ± 12.5 | 27.2–257 | / | / |

| 15ADON | 7 | 4.64 | 76.2 ± 7.63 | 16.0–188 | / | / |

| DOM b | 6 | 3.97 | 81.5 ± 7.22 | 32.0–135 | / | / |

| ENNA | 6 | 3.97 | 110 ± 14.4 | 6.02–393 | / | / |

| NIV | 3 | 1.99 | 33.7 ± 4.11 | 6.42–86.9 | / | / |

| FB1 c | 1 | 0.66 | 14.4 | 14.4 | / | / |

| Mycotoxin | Mean Level of Fusarium toxins (μg/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. graminearum-15ADON | F. graminearum-3ADON | F. acuminatum | F. avenaceum | |

| DON | 232 ± 34.6 | 258 ± 45.9 | - | - |

| 3ADON | 9.46 ± 1.69 | 73.1 ± 42.6 | - | - |

| 15ADON | 41.7 ± 5.74 | 34.2 ± 5.47 | - | - |

| ZEN | 124 ± 23.0 | 176 ± 62.6 | - | - |

| ENNA | - | - | 29.1 ± 7.99 | 0.75 ± 0.51 |

| ENNA1 | - | - | 150 ± 31.2 | 13.1 ± 6.87 |

| ENNB | - | - | 234 ± 32.3 | 123 ± 55.2 |

| ENNB1 | - | - | 267 ± 50.4 | 57.0 ± 27.2 |

| Mycotoxin | Linearity (μg/kg) | R2 | LOD (μg/kg) | LOQ (μg/kg) | Spiked (μg/kg) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DON | 10.0~2000 | 0.999 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10.0, 20.0, 100.0 | 87.6, 96.8, 95.2 | 6.8, 5.9, 1.8 |

| 3ADON | 10.0~2000 | 0.999 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10.0, 20.0, 100.0 | 86.4, 108, 104 | 4.3, 3.6, 3.2 |

| 15ADON | 10.0~2000 | 0.998 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10.0, 20.0, 100.0 | 84.4, 103, 106 | 3.6, 3.0, 2.9 |

| 4ANIV | 10.0~2000 | 0.999 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 84.2, 101, 94.7 | 6.9, 5.8, 4.7 |

| NIV | 5.0~1000 | 0.999 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 83.3, 88.6, 90.7 | 2.8, 3.1, 2.6 |

| FB1 | 5.0~1000 | 0.999 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 85.8, 84.9, 83.4 | 2.6, 1.5, 1.7 |

| FB2 | 5.0~1000 | 0.998 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 84.7, 88.3, 85.9 | 6.8, 3.2, 6.9 |

| FB3 | 5.0~1000 | 0.998 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 96.1, 92.9, 95.7 | 6.5, 6.1, 8.2 |

| T-2 | 5.0~1000 | 0.998 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 92.2, 105, 97.5 | 8.6, 3.2, 3.2 |

| HT-2 | 5.0~1000 | 0.997 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 102, 109, 113 | 7.5, 2.4, 3.1 |

| NEO | 5.0~1000 | 0.998 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 89.6, 95.3, 93.5 | 8.7, 2.9, 4.9 |

| DOM | 5.0~1000 | 0.997 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 109, 102, 96.4 | 3.6, 5.9, 3.6 |

| DAS | 5.0~1000 | 0.998 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 94.1, 108, 95.2 | 5.3, 5.8, 6.2 |

| BEA | 5.0~1000 | 0.999 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 83.2, 87.3, 86.0 | 3.2, 3.2, 2.3 |

| ENNA | 5.0~1000 | 0.999 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 76.8, 84.3, 78.8 | 1.3, 2.5, 0.8 |

| ENNA1 | 5.0~1000 | 0.999 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 86.5, 85.2, 78.9 | 2.2, 2.7, 2.4 |

| ENNB | 5.0~1000 | 0.998 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 79.9, 85.6, 89.2 | 1.8, 2.4, 1.3 |

| ENNB1 | 5.0~1000 | 0.999 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.0, 10.0, 50.0 | 86.8, 90.0, 86.4 | 2.3, 2.9, 1.9 |

| ZEN | 1.0~200 | 0.999 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.0, 2.0, 10.0 | 76.8, 84.3, 78.8 | 2.9, 2.1, 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; He, C.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Shi, J.; et al. Natural Occurrence of Conventional and Emerging Fusarium Mycotoxins in Freshly Harvested Wheat Samples in Xinjiang, China. Toxins 2025, 17, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120591

Zheng W, Zhang J, Shi Y, He C, Zhou X, Jiang J, Wang G, Zhang J, Xu J, Shi J, et al. Natural Occurrence of Conventional and Emerging Fusarium Mycotoxins in Freshly Harvested Wheat Samples in Xinjiang, China. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120591

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Weihua, Jinyi Zhang, Yi Shi, Can He, Xiaolong Zhou, Junxi Jiang, Gang Wang, Jingbo Zhang, Jianhong Xu, Jianrong Shi, and et al. 2025. "Natural Occurrence of Conventional and Emerging Fusarium Mycotoxins in Freshly Harvested Wheat Samples in Xinjiang, China" Toxins 17, no. 12: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120591

APA StyleZheng, W., Zhang, J., Shi, Y., He, C., Zhou, X., Jiang, J., Wang, G., Zhang, J., Xu, J., Shi, J., Dong, F., & Sun, T. (2025). Natural Occurrence of Conventional and Emerging Fusarium Mycotoxins in Freshly Harvested Wheat Samples in Xinjiang, China. Toxins, 17(12), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120591