Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans and Fish—A Review

Abstract

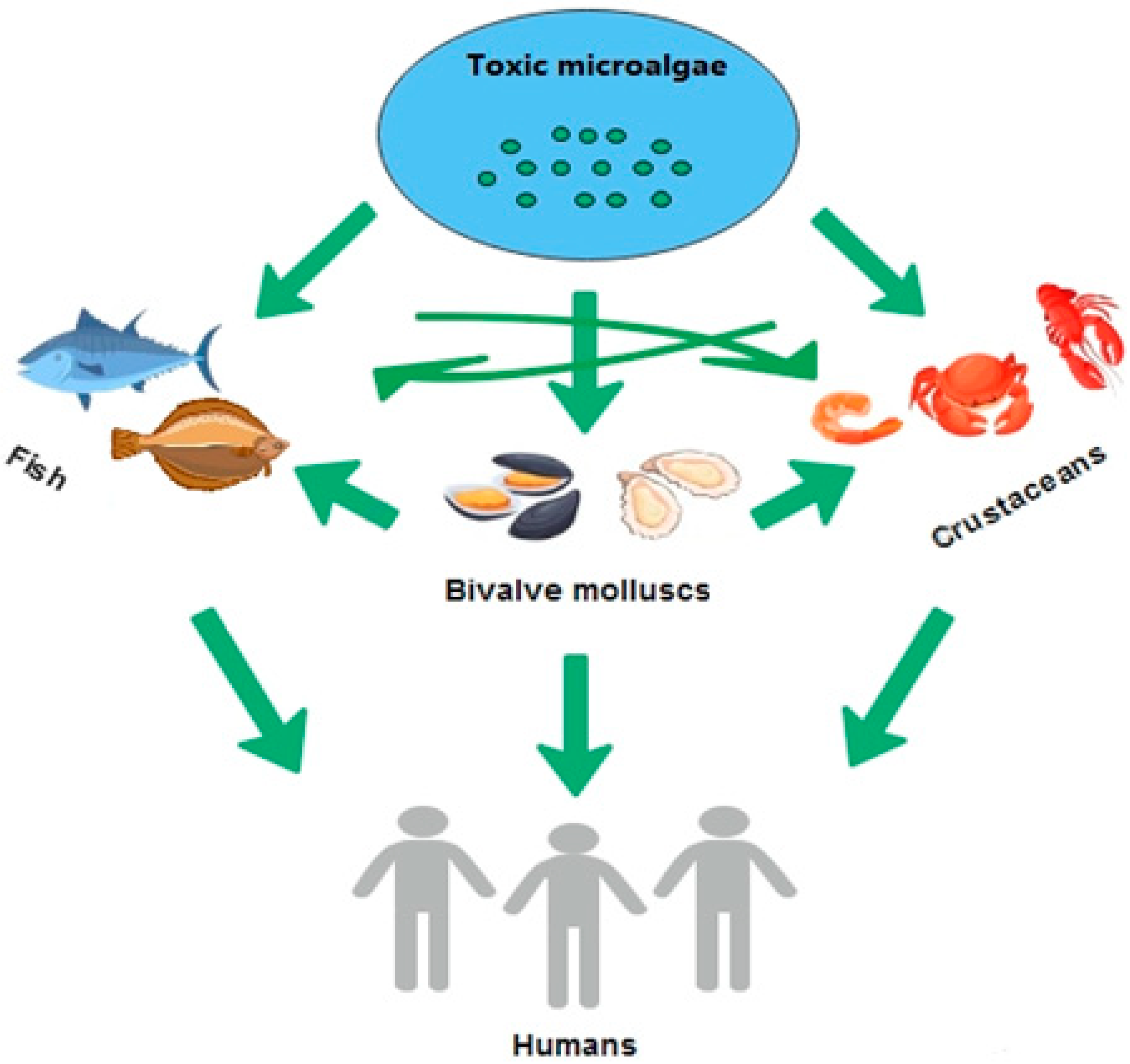

1. Introduction

Seafood Production and Global Market

2. Challenges in the Detection of Marine Biotoxins

3. Occurrence of Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans

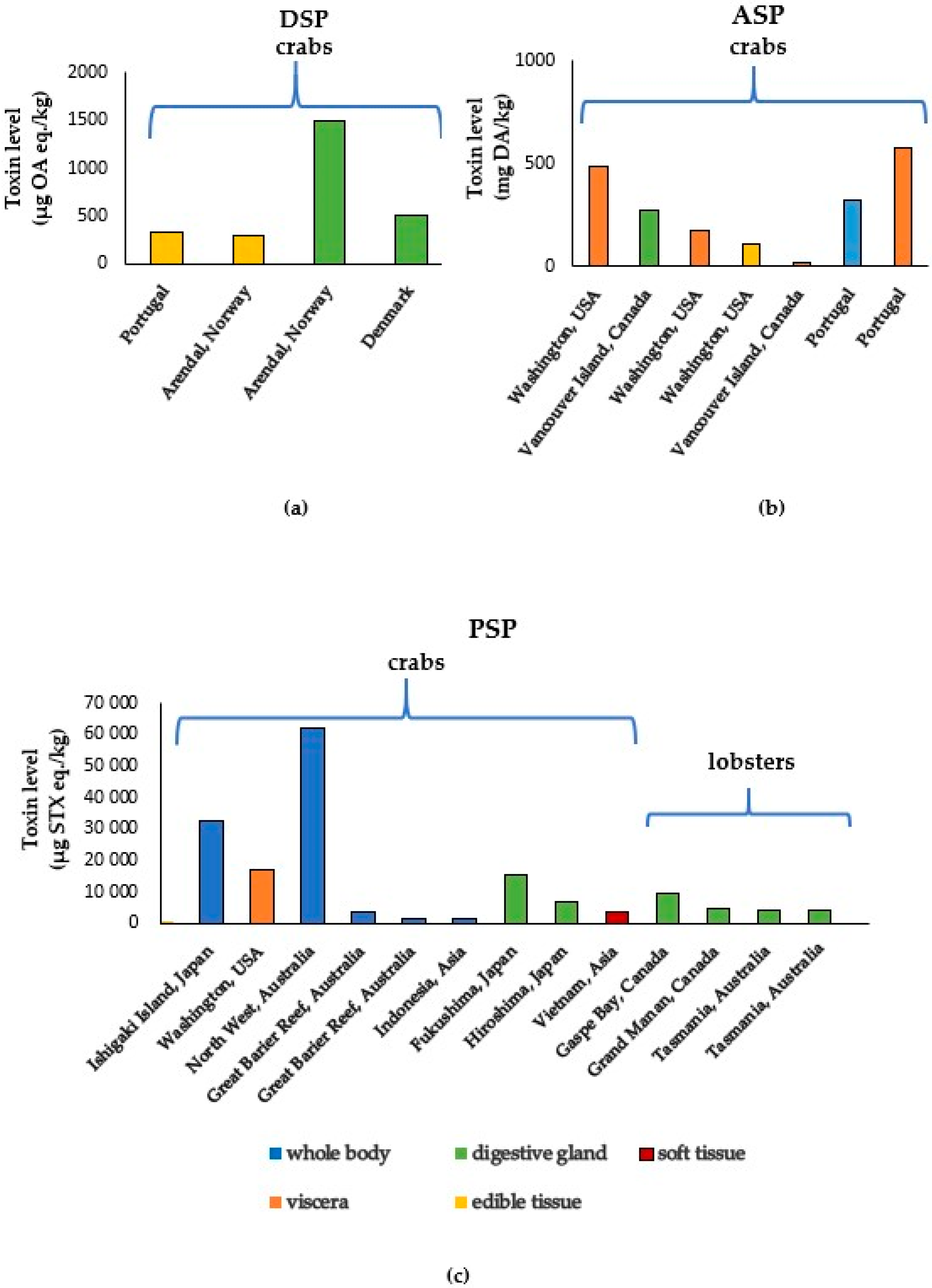

3.1. Marine Biotoxins in Crabs

3.2. Marine Biotoxins in Lobsters

3.3. Marine Biotoxins in Shrimps

4. Fish as Non-Bivalve Vectors for Marine Biotoxins

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASP | Amnesic shellfish poisoning |

| AZP | Azaspiracid shellfish poisoning |

| BTX | Brevetoxin |

| CTX | Ciguatoxin |

| DSP | Diarrhetic shellfish poisoning |

| DTX | Dinophysistoxin |

| HILIC-MS/MS | Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry |

| HPLC-FLD | High-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection |

| HPLC-UV | High-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry |

| MBA | Mouse bioassay |

| PSP | Paralytic shellfish poisoning |

| PTX | Palytoxin |

| TTX | Tetrodotoxin |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry |

| YTX | Yessotoxoin |

References

- Paz, O.; Marisa, S. Emerging marine biotoxins in european waters: Potential risks and analytical challenges. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farabegoli, F.; Blanco, L.; Rodríguez, L.P.; Vieites, J.M.; Cabado, A.G. Phycotoxins in marine shellfish: Origin, ocurrence and effects on humans. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visciano, P.; Schirone, M.; Berti, M.; Milandri, A.; Tofalo, R.; Suzzi, G. Marine biotoxins: Occurrence, toxicity, regulatory Limits and reference methods. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.R.; Costa, S.T.; Braga, A.C.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Vale, P. Relevance and challenges in monitoring marine biotoxins in non-bivalve vectors. Food Control 2017, 76, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzao, M.C.; Vilarino, N.; Vale, C.; Costas, C.; Cao, A.; Raposo-Garcia, S.; Vieytes, M.R.; Botana, L.M. Current trends and new challenges in marine phycotoxins. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for the hygiene of foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2004, 139, 55–205. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004R0853&qid=1764432595843 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products. Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, 95, 1–142. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/625/2025-01-05 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Estevez, P.; Castro, D.; Pequeño-Valtierra, A.; Giraldez, J.; Gago-Martinez, A. Emerging marine biotoxins in seafood from European coasts: Incidence and analytical challenges. Foods 2019, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerssen, A.; Pol-Hofstad, I.E.; Poelman, M.; Mulder, P.P.J.; Van den Top, H.J.; De Boer, J. Marine toxins: Chemistry, toxicity, occurrence and detection, with special reference to the Dutch situation. Toxins 2010, 2, 878–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Panel on contaminants in the food chain (CONTAM). Scientific opinion on marine biotoxins in shellfish—Palytoxin group. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on marine biotoxins in shellfish—Cyclic imines (spirolides, gymnodimines, pinnatoxins and pteriatoxins). EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific opinion on marine biotoxins in shellfish—Emerging toxins: Ciguatoxin group. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, P.; Sampayo, M.A.D.M. First confirmation of human diarrhoeic poisonings by okadaic acid esters after ingestion of razor clams (Solen marginatus) and green crabs (Carcinus maenas) in Aveiro lagoon, Portugal and detection of okadaic acid esters in phytoplankton. Toxicon 2002, 40, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, T.; Aasen, J.; Aune, T. Diarrhetic shellfish poisoning by okadaic acid esters from Brown crabs (Cancer pagurus) in Norway. Toxicon 2005, 46, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castberg, T.; Torgersen, T.; Aasen, J.; Aune, T.; Naustvoll, L.J. Diarrhoetic shellfish poisoning toxins in Cancer pagurus L., 1758 (Brachyura, Cancridae) in Norwegian waters. Sarsia 2004, 89, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation. Part 1 World Review; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in Action. Part 1 World Review; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Mansour, S.T.; Nouh, R.A.; Khattab, A.R. Crustaceans (shrimp, crab, and lobster): A comprehensive review of their potential health hazards and detection methods to assure their biosafety. J. Food Saf. 2022, 13026, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanasamy, A.; Balde, A.; Raghavender, P.; Shashanth, D.; Abraham, J.; Joshi, I.; Abdul, N.R. Isolation of marine crab (Charybdisnatator) leg muscle peptide and its anti-inflammatory effects on mac-rophage cells. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 25, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Gopakumar, K. Shellfish: Nutritive value, health benefits, and consumer safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 1219–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowaiye, A.; Emenyeonu, L.; Nwonu, E.J.; Abakpa, G.O.; Bur, D.; Ibeanu, G. The Potential of Biotoxins for Drug Discovery and Development. In Biotoxins in Food, Threats and Benefits, 1st ed.; Aransiola, S.A., Kotun, B.C., Maddela, N.G., Eds.; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament Commission. European Parliament Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627 of 15 March 2019 laying down uniform practical arrangements for the performance of official controls on products of animal origin intended for human consumption in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council and amending Commission Regulation (EC) No 2074/2005 as regards official controls. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L131, 51–100. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2019/627/2025-08-10 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Bian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.S.; Gao, H.Y. Marine toxins in seafood: Recent updates on sample pretreatment and determination techniques. Food Chem. 2024, 438, 137995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassolas, A.; Hayat, A.; Catanante, G.; Marty, J.L. Detection of the marine toxin okadaic acid: Assessing seafood safety. Talanta 2013, 105, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K.; Cold, U.; Fischer, K. Accumulation and depuration of okadaic acid esters in the European green crab (Carcinus maenas) during a feeding study. Toxicon 2008, 51, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, P.; Sampayo, M.A.D.M. Domoic acid in Portuguese shellfish and fish. Toxicon 2001, 39, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, C.L.; Gauglitz, E.J., Jr.; Barnett, H.J.; Lund, J.A.K.; Wekell, J.C.; Eklund, A.M. The fate of domoic acid in Dungeness crab (Cancer magister) as a function of processing. J. Shellfish Res. 1995, 14, 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.R.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Botelho, M.J.; Sampayo, M.A.D.M. A potential vector of domoic acid: The swimming crab Polybius henslowii Leach (Decapoda-brachyura). Toxicon 2003, 42, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, P.; Gallacher, S.; Bates, L.A.; Brown, N.; Quilliam, M.A. Determination and confirmation of the Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning toxin, domoic acid, in shellfish from Scotland by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. J. AOAC Int. 2001, 84, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwein, D.M.; Foster, K.; Doose, G.; Newton, R.T. The detection and distribution of the marine neurotoxin domoic acid on the Pacific Coast of the United States 1991–1993. J. Shellfish Res. 1995, 14, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway, S.E. Phycotoxin-Related shellfish poisoning: Bivalve molluscs are not the only vectors. Rev. Fish. Sci. 1995, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeds, J.R. Non-Traditional Vectors for Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 308–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How, C.K.; Chern, C.H.; Huang, Y.C.; Wang, L.M.; Lee, C.H. Tetrodotoxin poisoning. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 21, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, O.; Noguchi, T.; Shida, Y.; Onoue, Y. Occurrence of carbamoyl-N-hydroxyderivatives of saxitoxin and neosaxitoxin in a xanthid crab Zosimus aeneus. Toxicon 1994, 32, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, O.; Nishio, S.; Noguchi, T.; Shida, Y.; Onoue, Y. A new saxitoxin analogue from a Xanthid crab Atergatis floridus. Toxicon 1995, 33, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, L.E. Haemolymph protein in xanthid crabs: Its selective binding of saxitoxin and possible role in toxin bioaccumulation. Mar. Biol. 1997, 128, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, A.; Llewellyn, L. Comparative analyses by HPLC and the sodium channel and saxiphilin 3H-saxitoxin receptor assays for paralytic shellfish toxins in crustaceans and molluscs from tropical North West Australia. Toxicon 1998, 36, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, K.; Noguchi, T.; Uzu, A.; Hashimoto, K. Individual, local, and size-dependent variations in toxicity of the xanthid crab Zosimus aeneus. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 1983, 49, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Ho, P.H.; Hwang, C.C.; Hwang, P.A.; Cheng, C.A.; Hwang, D.F. Tetrodotoxin in several species of xanthid crabs in southern Taiwan. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, H.V.; Takata, Y.; Sato, S.; Fukuyo, Y.; Kodama, M. Frequent occurrence of the tetrodotoxin-bearing horseshoe crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda in Vietnam. Fish. Sci. 2009, 75, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.; Malhi, N.; Tan, J.; Harwood, D.T.; Madigan, T. Fate of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in Southern Rock Lobster (Jasus edwardsii) during Cooking: Concentration, Composition, and Distribution. J. Food Protect. 2018, 81, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NZRLIC. National Marine Biotoxin Risk Management Plan for the New Zealand Rock Lobster Industry; New Zealand Rock Lobster Industry Council: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024; Available online: https://nzrocklobster.co.nz/documents/nationalmarinebiotoxinriskmanagementplan/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- California Ocean Science Trust. Frequently Asked Questions: Harmful Algal Blooms and California Fisheries. California Ocean Science Trust. Available online: https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=128577 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- CDFW. Health Advisories and Closures for California Finfish, Shellfish and Crustaceans. Available online: https://wildlife.ca.gov/Fishing/Ocean/Health-Advisories (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Madigan, T.; Tan, J.; Malhi, N.; McLeod, C.; Turnbull, A. Understanding and Reducing the Impact of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in Southern Rock Lobster; FRDC Report 2013/713; South Australian Research and Development Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017.

- Turnbull, A.; Malhi, N.; Seger, A.; Harwood, T.; Jolley, J.; Fitzgibbon, Q.; Hallegraeff, G. Paralytic shellfish toxin uptake, tissue distribution, and depuration in the Southern Rock Lobster Jasus edwardsii Hutton. Harmful Algae 2020, 95, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephton, D.H.; Haya, K.; Martin, J.L.; LeGresley, M.M.; Page, F.H. Paralytic shellfish toxins in zooplankton, mussels, lobsters and caged Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, during a bloom of Alexandrium fundyense off Gran Manan Island, in the Bay of Fundy. Harmful Algae 2007, 6, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.S.; Beach, D.G.; Comeau, L.A.; Haigh, N.; Lewis, N.I.; Locke, A.; Martin, J.L.; McCarron, P.; McKenzie, C.H.; Michel, C.; et al. Marine Harmful Algal Blooms and Phycotoxins of Concern to Canada. Can. Technol. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 3384, 1–322. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans Inspection Branch. Summary of Marine Toxin Records in the Pacific Region, 2250 South Boundary Road, Burnaby, Canada 1994, p. 90. Available online: https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/40610949.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Oikawa, H.; Matsuyama, Y.; Satomi, M.; Yano, Y. Accumulation of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxin by the swimming crab Charybdis japonica in Kure Bay, Hiroshima Prefecture. Fish. Sci. 2008, 74, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, C.; Kiermeier, A.; Stewart, I.; Tan, J.; Turnbull, A.; Madigan, T. Paralytic shellfish toxins in Australian Southern Rock Lobster (Jasus edwardsii): Acute human exposure from consumption of hepatopancreas. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2018, 24, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, L.E.; Dodd, M.J.; Robertson, A.; Ericson, G.; De Koning, C.; Negri, A.P. Post-mortem analysis of samples from a human victim of a fatal poisoning caused by the xanthid crab, Zosimus aeneus. Toxicon 2002, 40, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, L.E.; Endean, R. Toxins extracted from Australian specimens of the crab, Eriphia sebana (Xanthidae). Toxicon 1989, 27, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikawa, H.; Fujita, T.; Saito, K.; Satomi, M.; Yano, Y. Difference in the level of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxin accumulation between the crabs Telmessus acutidens and Charybdis japonica collected in Onahama, Fukushima Prefecture. Fish. Sci. 2007, 73, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Linares, J.; Ochoa, J.L.; Gago-Martinez, A. Effect of PSP Toxins in White Leg Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Boone, 1931. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Altamirano, R.; Manrique, F.A.; Luna-Soria, R. Harmful phytoplankton blooms in shrimp farms from Sinaloa, Mexico. In Abstracts of VIII International Conference on Harmful Algae, Proceedings of the VIII International Conference on Harmful Algae, Vigo, Spain, 25–29 June 1997; Instituto Espanol de Oceanografia: Madrid, Spain, 1997; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Rodrıguez, R.; Paez-Osuna, F. Nutrients, phytoplankton and harmful algal blooms in shrimp ponds: A review with special reference to the situation in the Gulf of California. Aquaculture 2003, 219, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Linares, J.; Cadena, M.; Rangel, C.; Unzueta-Bustamante, M.L.; Ochoa, J.L. Effect of Schizotrix calcicola on white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Penaeus vannamei) postlarvae. Aquaculture 2003, 218, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Linares, J.; Ochoa, J.L.; Gago-Martinez, A. Retention and tissue damage of PSP and NSP toxins in shrimp: Is cultured shrimp a potential vector of toxins to human population? Toxicon 2009, 53, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Z.; Dan, W. Effects of toxic Alexandrium species on the surbvival and feeding rates of brine shrimp Artemia salina. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2006, 26, 3942–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Hui, X.; Wang, G.-X. The developmental toxicity, bioaccumulation and distribution of oxidized single walled carbon nanotubes in Artemia salina. Toxicol. Res. 2018, 7, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, B.R.; Tanaka, K.; Doyle, J.E.; Chu, K.H. A change of heart: Cardiovascular development in the shrimp Metapenaeus ensis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 133, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, G.; Meulebroek, L.V.; Rijcke, M.D.; Janssen, C.R.; Vanhaecke, L. High resolution mass spectrometry-based screening reveals lipophilic toxins in multiple trophic levels from the North Sea. Harmful Algae 2017, 64, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson, B.; Andersen, P.; Arneborg, L.; Cembella, A.; Eikrem, W.; John, U.; West, J.J.; Klemm, K.; Kobos, J.; Lehtinen, S.; et al. Harmful algal blooms and their effects in coastal seas of northern Europe. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickey, R.W.; Plakas, S.M. Ciguatera: A public health perspective. Toxicon 2010, 56, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbister, G.K.; Kiernan, M.C. Neurotoxic marine poisoning. Lancet Neurol. 2005, 4, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleibs, S.; Mebs, D.; Werding, B. Studies on the origin and distribution of palytoxin in Caribbean coral reef. Toxicon 1995, 33, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeds, J.R.; Schwartz, M.D. Human risk associated with palytoxin exposure. Toxicon 2010, 56, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, A.M.; Hokama, Y.; Yasumoto, T.; Fukui, M.; Manea, S.J.; Sutherland, N. Clinical and laboratory findings implicating palytoxin as cause of ciguatera poisoning due to Decapterus macrosoma (mackerel). Toxicon 1989, 27, 1051–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniyama, S.; Mahmud, Y.; Terada, M.; Takatani, T.; Arakawa, O.; Noguchi, T. Occurrence of a food poisoning incident by palytoxin from a serranid Epinephelus sp. in Japan. J. Nat. Toxins 2002, 11, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okano, H.; Masuoka, H.; Kamei, S.; Seko, T.; Koyabu, S.; Tsuneoka, K.; Tamai, T.; Ueda, K.; Nakazawa, S.; Sugawa, M.; et al. Rhabdomyolysis and myocardial damage induced by palytoxin, a toxin of blue humphead parrotfish. Internal Med. 1998, 37, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipiä, V.; Kankaanpää, H.; Meriluoto, J.; Høisæter, T. The first observation of okadaic acid in flounder in the Baltic Sea. Sarsia 2000, 85, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriere, M.; Soliño, L.; Costa, P.R. Effects of the marine biotoxins okadaic acid and dinophysistoxins on fish. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.P.; Mafra, L.L. Diel variations in cell abundance and trophic transfer of diarrheic toxins during massive Dinophysis bloom in southern Brazil. Toxins 2018, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souid, G.; Souayed, N.; Haouas, Z.; Maaroufi, K. Does the phycotoxin okadaic acid cause oxidative stress damages and histological alterations to seabream (Sparus aurata)? Toxicon 2018, 144, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, R.A.F.; Nascimento, S.M.; Santos, L.N. Sublethal fish responses to short-term food chain transfer of DSP toxins: The role of somatic condition. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2020, 524, 151317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, K.A.; Silver, M.W.; Coale, S.L.; Tjeerdema, R.S. Domoic acid in planktivorous fish in relation to toxic Pseudo-nitzschia cell densities. Mar. Biol. 2002, 140, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bane, V.; Lehane, M.; Dikshit, M.; O’Riordan, A.; Furey, A. Tetrodotoxin: Chemistry, toxicity, source, distribution, and detection. Toxins 2014, 6, 693–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, Y.; Arakawa, O.; Noguchi, T. An epidemic survey on freshwater puffer poisoning in Bangladesh. J. Nat. Toxins 2000, 9, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kodama, M.; Ogata, T.; Kawamukai, K.; Oshima, Y.; Yasumoto, T. Toxicity of muscle and other organs of five species of puffer collected from the Pacific coast of Tohoku area of Japan. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 1984, 50, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Ogata, T.; Borja, V.; Gonzales, C.; Fukuyo, Y.; Kodama, M. Frequent occurrence of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins as dominant toxins in marine puffer from tropical water. Toxicon 2000, 38, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.P.; Flewelling, L.J.; Landsberg, J.H. Saxitoxin monitoring in three species of Florida puffer fish. Harmful Algae 2009, 8, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K.; Arakawa, O.; Taniyama, S.; Nonaka, M.; Takatani, T.; Yamamori, K.; Fuchi, Y.; Noguchi, T. Occurrence of saxitoxins as a major toxin in the ovary of a marine puffer Arothron firmamentum. Toxicon 2004, 43, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvao, J.A.; Oetterer, M.; do Carmo Bittencourt-Oliveira, M.; Gouvea-Barros, S.; Hiller, S.; Erler, K.; Luckas, B.; Pinto, E.; Kujbida, P. Saxitoxins accumulation by freshwater tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) for human consumption. Toxicon 2009, 54, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Marine biotoxins in shellfish—Saxitoxin group Scientific opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain. EFSA J. 2009, 1019, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Shimizu, N.; Nakazawa, H. Determination of tetrodotoxin in puffer-fish by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Analyst 2002, 127, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbora, H.D.; Kunter, İ.; Erçetin, T.; Elagöz, A.M.; Çiçek, B.A. Determination of tetrodotoxin (TTX) levels in various tissues of the silver cheeked puffer fish (Lagocephalus sceleratus (Gmelin, 1789) in Northern Cyprus Sea (Eastern Mediterranean). Toxicon 2020, 175, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Sosa, M.J.; García-Álvarez, N.; Sanchez-Henao, A.; Sergent, F.S.; Padilla, D.; Estévez, P.; Caballero, M.J.; Martín-Barrasa, J.L.; Gago-Martínez, A.; Diogène, J.; et al. Ciguatoxin Detection in Flesh and Liver of Relevant Fish Species from the Canary Islands. Toxins 2022, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Marine Biotoxin | Group | Regulatory Limit | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated marine toxins in the EU | |||

| Saxitoxins | STx | 800 µg STX eq.2-HCl/kg | HPLC-FLD * |

| Domoic acid | DA | 20 mg DA/kg | HPLC-UV * |

| Okadaic acid | OA | 160 µg OA eq./kg | LC-MS/MS * |

| Azaspiracids | AZAs | 160 µg AZA eq./kg | LC-MS/MS * |

| Yessotoxins | YTXs | 3.75 mg YTX eq./kg | LC-MS/MS * |

| Emerging marine toxins (not regulated in the EU) | |||

| Brevetoxins | BTx | NE ** | LC-MS/MS |

| Ciguatoxins | CTx | NE ** | LC-MS/MS |

| Cyclic imines | CIs | NE ** | UPLC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS, |

| Tetrodotoxins | TTx | NE ** | HILIC-MS/MS, UPLC-MS/MS |

| Palytoxins | PTXs | NE ** | LC-MS/MS |

| Species | Toxin | Toxin Concentration | Analyzed Tissue | Area | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 221,040 µg STXeq./kg | Gonads | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2004 | [82] |

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 201,060 µg STXeq./kg | Muscle tissue | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 172,360 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 136,660 µg STXeq./kg | Gut contents | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 47,020 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida, Tequesta | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 33,260 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida, Tampa Bay | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Southern Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides nephelus) | PSP | 12,830 µg STXeq./kg | Gonads | Florida, Jacksonville | 2002–2005 | [82] |

| Checkered Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides testudineus) | PSP | 15,050 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida, Tequesta | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Checkered Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides testudineus) | PSP | 3080 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Checkered Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides testudineus) | PSP | 2650 µg STXeq./kg | Gut contents | Florida, Tequesta | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Checkered Puffer Fish (Sphoeroides testudineus) | PSP | 1890 µg STXeq./kg | Gonads | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Bandtail puffer fish (Sphoeroides spengleri) | PSP | 18,320 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Bandtail puffer fish (Sphoeroides spengleri) | PSP | 17,780 µg STXeq./kg | Muscle | Florida, Tequesta | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Bandtail puffer fish (Sphoeroides spengleri) | PSP | 15,340 µg STXeq./kg | Skin | Florida Keys | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Bandtail puffer fish (Sphoeroides spengleri) | PSP | 14,280 µg STXeq./kg | Gut contents | Florida, Indian River Lagoon | 2002–2006 | [82] |

| Starry toado puffer fish (Arothron firmamentum) | PSP | 133,200 µg STXeq./kg * | Ovary | Japan, Iwate | 2000 | [83] |

| Starry toado puffer fish (Arothron firmamentum) | PSP | 27,360 µg STXeq./kg * | Ovary | Japan, Oita Prefecture | 1995 | [83] |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PSP | 300 µg STXeq./kg | Muscle | Brazil, Sao Paulo | 2005 | [84] |

| Starry toado puffer fish (Arothron firmamentum) | TTX | 6600 µg TTXeq./kg ** | Skin | Japan, Oita Prefecture | 1995 | [85] |

| Torafugu puffer fish (Takifugu Rubripes) | TTX | 880,000 µg TTXeq./kg | Liver | Japan, Saitama Prefecture | 2000 | [86] |

| Torafugu puffer fish (Takifugu Rubripes) | TTX | 352,000 µg TTXeq./kg | Ovary | Japan, Saitama Prefecture | 2000 | [86] |

| Silver cheeked puffer fish (Lagocephalus sceleratus) | TTX | 13,480 µg TTXeq./kg | Liver | Northern Cyprus Sea | 2017–2018 | [87] |

| Amberjack (Seriola spp.) | CTX | 6.439 µg CTX1Beq./kg | Liver | Canary Islands | 2016–2019 | [88] |

| Black Moray Eel (Muraena helena) | CTX | 6.062 µg CTX1Beq./kg | Liver | Canary Islands | 2016–2019 | [88] |

| Flounder (Platichthys flesus) | DSP | 222 µg OA/kg | Liver | Baltic Sea, Gulf of Finland | 1996 | [72] |

| Atlantic Anchoveta (Cetengraulis edentulus) | DSP | 44.7 µg OA/kg | Guts + liver | Brazil, Paranagua | 2011 | [73] |

| Blenny fish (Hypleurochilus fissicornis) | DSP | 59.3 µg OA/kg | Viscera | Brazil, Santa Catarina | 2016 | [74] |

| Anchovy (Engraulis mordax) | ASP | 1815; 1175; 1600; 1050; 507; 288 mg DA/kg | Viscera | California, Monterey Bay | 2000 | [77] |

| Sardines (Sardinops sagax) | ASP | 588; 558; 551; 386; 279; 216; 169 mg DA/kg | Viscera | California, Monterey Bay | 2000 | [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madejska, A.; Osek, J. Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans and Fish—A Review. Toxins 2025, 17, 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120589

Madejska A, Osek J. Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans and Fish—A Review. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):589. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120589

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadejska, Anna, and Jacek Osek. 2025. "Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans and Fish—A Review" Toxins 17, no. 12: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120589

APA StyleMadejska, A., & Osek, J. (2025). Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans and Fish—A Review. Toxins, 17(12), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120589