Heterologous Expression, Enzymatic Characterization, and Ameliorative Effects of a Deoxynivalenol (DON)-Degrading Enzyme in a DON-Induced Mouse Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Functional Validation of the DON-Degrading Enzyme (DDE)

2.2. Functional Validation of the DON-Degrading Enzyme DDE

2.3. Analysis of the Enzymatic Properties of the DON-Degrading Enzyme (DDE)

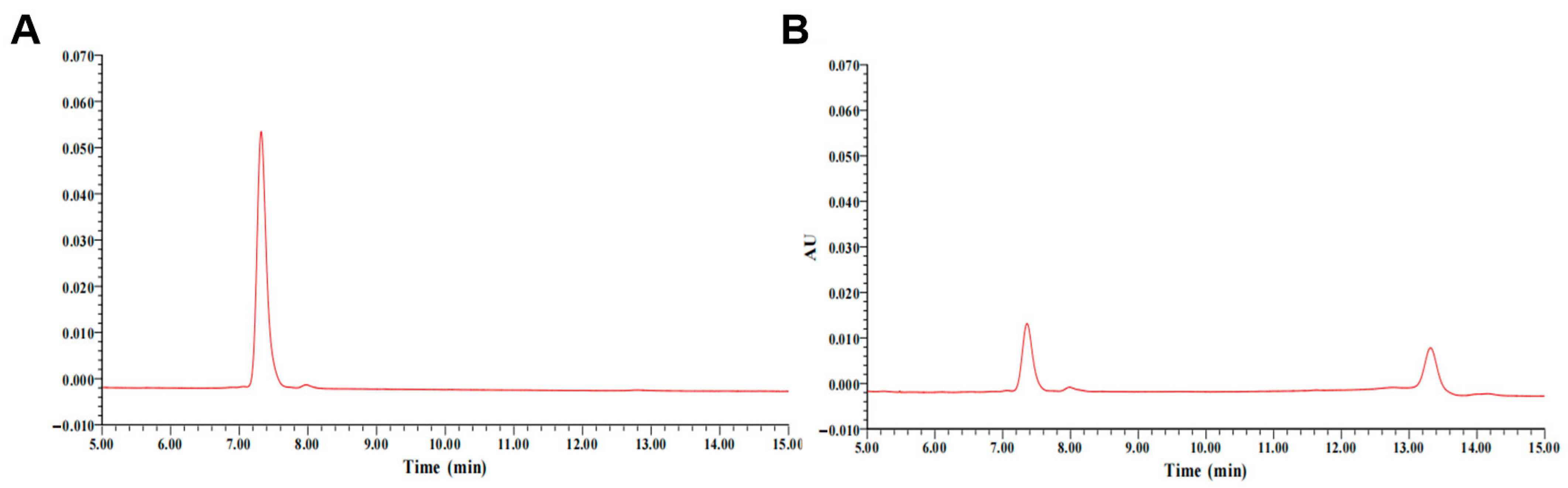

2.4. Detection of DDE-Catalyzed Metabolic Products

2.5. Effects of DON-Degrading Enzymes on Serum Biochemical Parameters, Liver Function, and Intestinal Health in DON-Exposed Mice

2.5.1. Effects of DDE on Organ Indices in DON-Exposed Mice

2.5.2. Effects of DDE on Physiological and Biochemical Indicators in DON-Exposed Mice

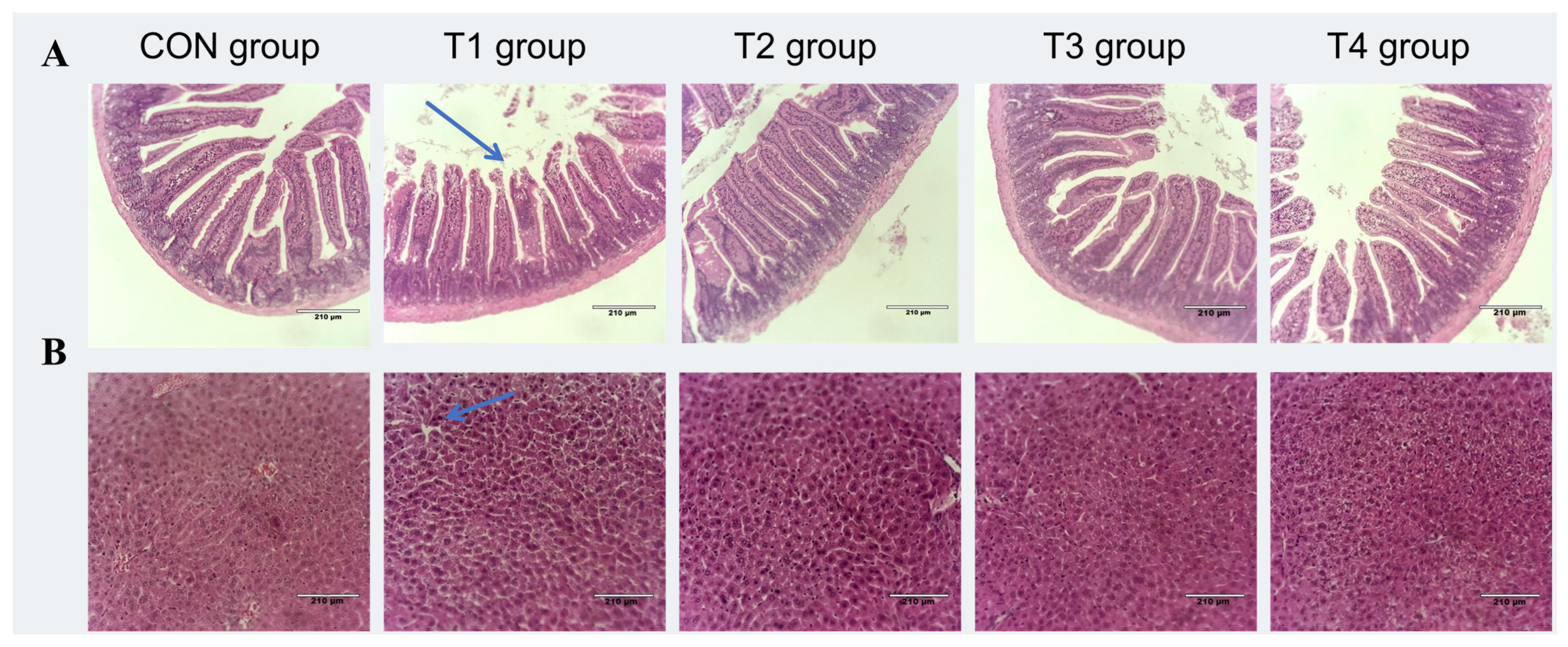

2.5.3. Effects of DDE on Intestinal and Liver Morphology in DON-Exposed Mic

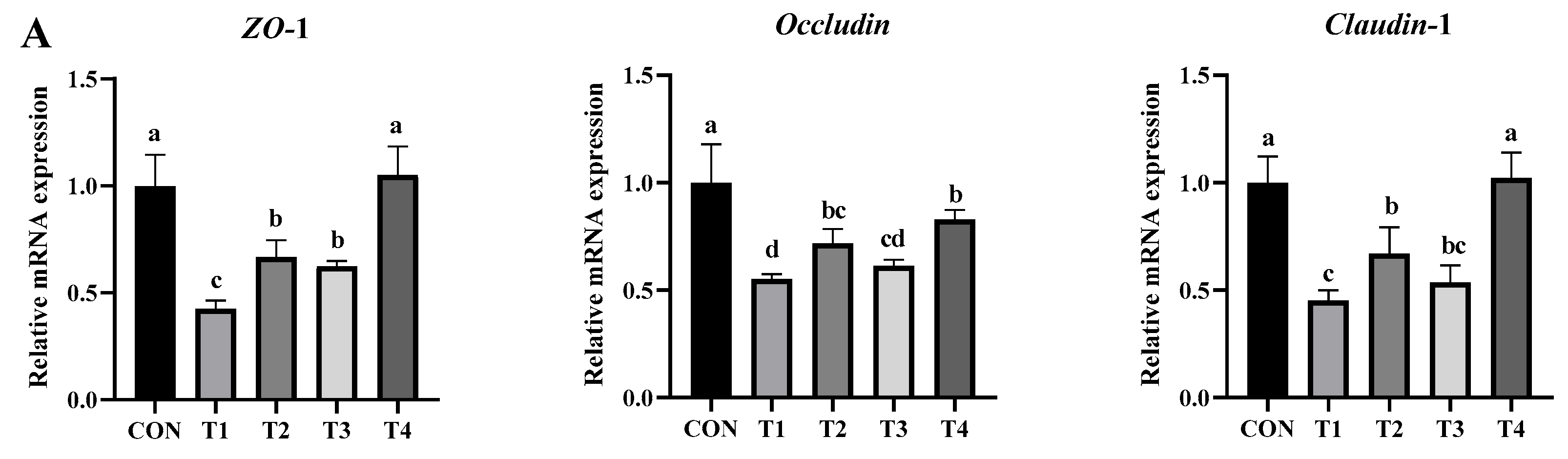

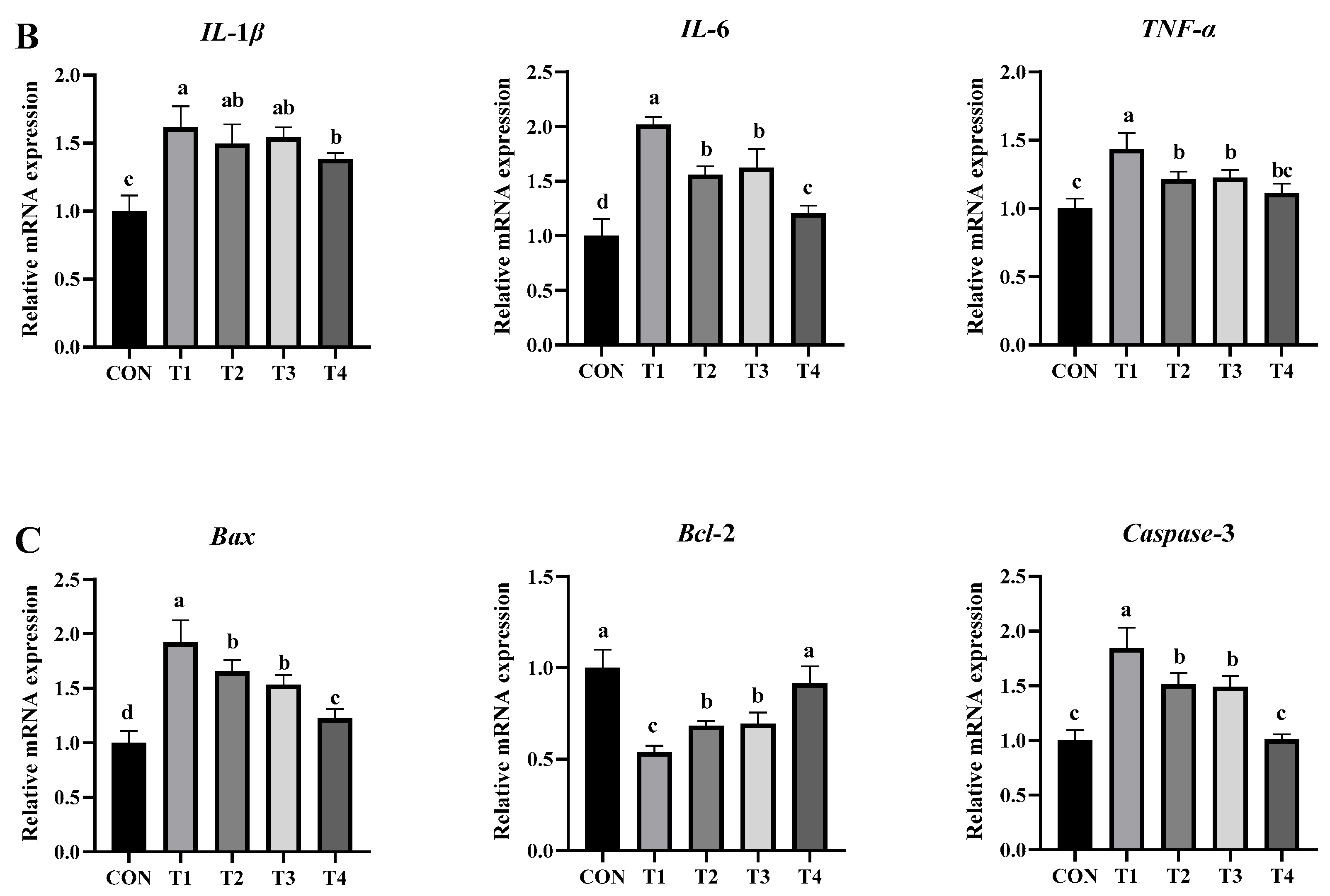

2.5.4. Effects of DDE on mRNA Expression of Genes Associated with Intestinal Inflammation, Barrier Function, and Apoptosis in DON-Exposed Mice

2.5.5. Effects of DDE on the Gut Microbiota of DON-Induced Mice

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. DON-Degrading Strains and Vectors

4.2. Heterologous Expression of DON-Degrading Enzyme DDE

4.2.1. Cloning of the DDE Gene and Construction of the Recombinant Vector

4.2.2. Expression and Purification of the Degrading Enzyme (DDE)

4.2.3. Validation of DDE-Degrading Enzyme Activity

4.2.4. Determination of DDE Degradation Enzyme Concentration

4.2.5. Analysis of the Properties of DDE

4.2.6. LC-MS Analysis of DDE Degradation Products

4.3. Effects of DON-Degrading Enzymes on DON-Induced Hepatointestinal Injury in Mice

4.3.1. Experimental Animals and Management

4.3.2. Experimental Design

4.3.3. Sample Collection and Processing

4.3.4. Measurement Parameters and Analytical Methods

4.4. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pestka, J.J. Deoxynivalenol: Mechanisms of action, human exposure, and toxicological relevance. Arch. Toxicol. 2010, 84, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber-Dorninger, C.; Jenkins, T.; Schatzmayr, G. Global Mycotoxin Occurrence in Feed: A Ten-Year Survey. Toxins 2019, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscoto, G.L.; Salvato, L.A.; Alvarenga, E.R.; Dias, R.R.S.; Pinheiro, G.R.G.; Rodrigues, M.P.; Pinto, P.N.; Freitas, R.P.; Keller, K.M. Mycotoxins in Cattle Feed and Feed Ingredients in Brazil: A Five-Year Survey. Toxins 2022, 14, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, S.; Scarpino, V.; Lanzanova, C.; Romano, E.; Reyneri, A. Multi-Mycotoxin Long-Term Monitoring Survey on North-Italian Maize over an 11-Year Period (2011–2021): The Co-Occurrence of Regulated, Masked and Emerging Mycotoxins and Fungal Metabolites. Toxins 2022, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Srivastava, S.; Dewangan, J.; Divakar, A.; Rath, S.K. Global occurrence of deoxynivalenol in food commodities and exposure risk assessment in humans in the last decade: A survey. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1346–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.-w.; Ling, H.-l.; Gao, C.-q.; Zhao, J.-c.; Yang, C.; Wang, X.-q. Methionine and Its Hydroxyl Analogues Improve Stem Cell Activity to Eliminate Deoxynivalenol-Induced Intestinal Injury by Reactivating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11464–11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Pan, X.; Zhou, H.-R.; Pestka, J.J. Modulation of Inflammatory Gene Expression by the Ribotoxin Deoxynivalenol Involves Coordinate Regulation of the Transcriptome and Translatome. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 131, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelusky, D.B.; Hartin, K.E.; Trenholm, H.L. Distribution of deoxynivalenol in cerebral spinal fluid following administration to swine and sheep. J. Environ. Sci. health. Part. B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes 1990, 25, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Dixit, S.; Dwivedi, P.D.; Pandey, H.P.; Das, M. Influence of temperature and pH on the degradation of deoxynivalenol (DON) in aqueous medium: Comparative cytotoxicity of DON and degraded product. Food Addit. Contam. Part A-Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neill, K.; Damoglou, A.; Patterson, M. The stability of deoxynivalenol and 3-acetyI deoxynivalenol to gamma irradiation. Food Addit. Contam. 1993, 10, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Cavret, S.; Laurent, N.; Videmann, B.; Mazallon, M.; Lecoeur, S. Assessment of deoxynivalenol (DON) adsorbents and characterisation of their efficacy using complementary in vitro tests. Food Addit. Contam. Part A-Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2010, 27, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretz, M.; Beyer, M.; Cramer, B.; Knecht, A.; Humpf, H.-U. Thermal degradation of the Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6445–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Subryan, L.M.; Potts, D.; McLaren, M.E.; Gobran, F.H. Reduction in levels of deoxynivalenol in contaminated wheat by chemical and physical treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1986, 34, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qin, X.; Tang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L. CotA laccase, a novel aflatoxin oxidase from Bacillus licheniformis, transforms aflatoxin B1 to aflatoxin Q1 and epi-aflatoxin Q1. Food Chem. 2020, 325, 126877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Qin, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Bin, Y.; Xie, X.; Zheng, F.; Luo, H. Biodegradation of Deoxynivalenol by Nocardioides sp. ZHH-013: 3-keto-Deoxynivalenol and 3-epi-Deoxynivalenol as Intermediate Products. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 658421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.W.; Hassan, Y.I.; Perilla, N.; Li, X.-Z.; Boland, G.J.; Zhou, T. Bacterial Epimerization as a Route for Deoxynivalenol Detoxification: The Influence of Growth and Environmental Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Ye, Y.; Sun, X. Microbial detoxification of mycotoxins in food and feed. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 4951–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qin, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Ji, C.; Zhao, L. Enzymatic degradation of deoxynivalenol by a novel bacterium, Pelagibacterium halotolerans ANSP101. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 140, 111276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.W.; Bondy, G.S.; Zhou, T.; Caldwell, D.; Boland, G.J.; Scott, P.M. Toxicology of 3-epi-deoxynivalenol, a deoxynivalenol-transformation product by Devosia mutans 17-2-E-8. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 84, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; He, J.; Young, J.C.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.-Z.; Ji, C.; Zhou, T. Transformation of trichothecene mycotoxins by microorganisms from fish digesta. Aquaculture 2009, 290, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlovsky, P. Biological detoxification of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol and its use in genetically engineered crops and feed additives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Mu, P.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Tang, S.; Wu, Y.; Miao, X.; Wang, X.; Wen, J.; Deng, Y. Dual Function of a Novel Bacterium, Slackia sp. D-G6: Detoxifying Deoxynivalenol and Producing the Natural Estrogen Analogue, Equol. Toxins 2020, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.-J.; Yuan, Q.-S.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Guo, M.-W.; Gong, A.-D.; Zhang, J.-B.; Wu, A.-B.; Huang, T.; Qu, B.; Li, H.-P.; et al. Aerobic De-Epoxydation of Trichothecene Mycotoxins by a Soil Bacterial Consortium Isolated Using In Situ Soil Enrichment. Toxins 2016, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, C. Methanol dehydrogenase, a PQQ-containing quinoprotein dehydrogenase. Sub-Cell. Biochem. 2000, 35, 73–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzner, S. Oxygenases without requirement for cofactors or metal ions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 60, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, B.W.; van Kleef, M.A.; Duine, J.A. Quinohaemoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase apoenzyme from Pseudomonas testosteroni. Biochem. J. 1986, 234, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, K.; Toyama, H.; Yamada, M.; Adachi, O. Quinoproteins: Structure, function, and biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 58, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, H.; Mathews, F.S.; Adachi, O.; Matsushita, K. Quinohemoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases: Structure, function, and physiology. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 428, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carere, J.; Hassan, Y.I.; Lepp, D.; Zhou, T. The enzymatic detoxification of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol: Identification of DepA from the DON epimerization pathway. Microb. Biotechnol. 2018, 11, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.-J.; Shi, M.-M.; Yang, P.; Huang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, A.-B.; Dong, W.-B.; Li, H.-P.; Zhang, J.-B.; Liao, Y.-C. A quinone-dependent dehydrogenase and two NADPH-dependent aldo/keto reductases detoxify deoxynivalenol in wheat via epimerization in a Devosia strain. Food Chem. 2020, 321, 126703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Ji, C.; Zhao, L. A quinoprotein dehydrogenase from Pelagibacterium halotolerans ANSP101 oxidizes deoxynivalenol to 3-keto-deoxynivalenol. Food Control 2022, 136, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carere, J.; Hassan, Y.I.; Lepp, D.; Zhou, T. The Identification of DepB: An Enzyme Responsible for the Final Detoxification Step in the Deoxynivalenol Epimerization Pathway in Devosia mutans 17-2-E-8. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.-J.; Zhang, L.; Yi, S.-Y.; Tang, X.-L.; Yuan, Q.-S.; Guo, M.-W.; Wu, A.-B.; Qu, B.; Li, H.-P.; Liao, Y.-C. An aldo-keto reductase is responsible for Fusarium toxin-degrading activity in a soil Sphingomonas strain. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikunaga, Y.; Sato, I.; Grond, S.; Numaziri, N.; Yoshida, S.; Yamaya, H.; Hiradate, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Toshima, H.; Koitabashi, M.; et al. Nocardioides sp. strain WSN05-2, isolated from a wheat field, degrades deoxynivalenol, producing the novel intermediate 3-epi-deoxynivalenol. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhou, D.; Ren, Z.; Deng, J. The PGC-1α/SIRT3 pathway mediates the effect of DON on mitochondrial autophagy and liver injury in mice. Mycotoxin Res 2025, 41, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Wang, M.; Grenier, B.; Ilic, S.; Ruczizka, U.; Dippel, M.; Buenger, M.; Hackl, M.; Nagl, V. MicroRNA Expression Profiling in Porcine Liver, Jejunum and Serum upon Dietary DON Exposure Reveals Candidate Toxicity Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zeng, D.; Wang, H.; Qing, X.; Sun, N.; Xin, J.; Luo, M.; Khalique, A.; Pan, K.; Shu, G.; et al. Dietary Probiotic Bacillus licheniformis H2 Enhanced Growth Performance, Morphology of Small Intestine and Liver, and Antioxidant Capacity of Broiler Chickens Against Clostridium perfringens-Induced Subclinical Necrotic Enteritis. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, H.; Zong, Q.; Ahmed, A.A.; Bao, W.; Liu, H.-Y.; Cai, D. Lactoferrin Relieves Deoxynivalenol-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response by Modulating the Nrf2/MAPK Pathways in the Liver. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8182–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, J.H.; Moukha, S.; Brou, K.; Gnakri, D. Lipid metabolism disorders, lymphocytes cells death, and renal toxicity induced by very low levels of deoxynivalenol and fumonisin b1 alone or in combination following 7 days oral administration to mice. Toxicol. Int. 2013, 20, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Huangfu, B.; Xing, F.; Xu, W.; He, X. Combined exposure to deoxynivalenol facilitates lipid metabolism disorder in high-fat-diet-induced obesity mice. Environ. Int. 2023, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutskii, K.M.; Gorshinskii, B.M. Serum and tissue aspartate and alanine aminotransferases activity of rats with vitamin A deficiency. Ukr. Biokhimichnyi Zhurnal 1976, 48, 444–446. [Google Scholar]

- Skiepko, N.; Przybylska-Gornowicz, B.; Gajecka, M.; Gajecki, M.; Lewczuk, B. Effects of Deoxynivalenol and Zearalenone on the Histology and Ultrastructure of Pig Liver. Toxins 2020, 12, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathumbi, P.; Mwangi, J.; Mugera, G.; Njiro, S. Biochemical and Haematological Changes Mediated by a Chloroform Extract of Prunus Africana Stem Bark in Rats. Pharm. Biol. 2000, 38, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, X.; Ma, J.; Shan, A. Low-dose deoxynivalenol exposure triggers hepatic excessive ferritinophagy and mitophagy mitigated by hesperidin modulated O-GlcNAcylation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, R.B.; Kubena, L.F.; Huff, W.E.; Elissalde, M.H.; Phillips, T.D. Hematologic and immunologic toxicity of deoxynivalenol (DON)-contaminated diets to growing chickens. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1991, 46, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Lin, L.; Li, P.; Tian, H.; Shen, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Qin, Y.; Tang, C. Selenomethionine protects the liver from dietary deoxynivalenol exposure via Nrf2/PPARγ-GPX4-ferroptosis pathway in mice. Toxicology 2024, 501, 153689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyarts, T.; Dänicke, S.; Valenta, H.; Ueberschär, K.H. Carry-over of Fusarium toxins (deoxynivalenol and zearalenone) from naturally contaminated wheat to pigs. Food Addit. Contam. Part A-Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2007, 24, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.E.; Al-Khalaifah, H.S.; Mohamed, W.A.M.; Gharib, H.S.A.; Osman, A.; Al-Gabri, N.A.; Amer, S.A. Effects of Phenolic-Rich Onion (Allium cepa L.) Extract on the Growth Performance, Behavior, Intestinal Histology, Amino Acid Digestibility, Antioxidant Activity, and the Immune Status of Broiler Chickens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 582612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolf-Clauw, M.; Castellote, J.; Joly, B.; Bourges-Abella, N.; Raymond-Letron, I.; Pinton, P.; Oswald, I.P. Development of a pig jejunal explant culture for studying the gastrointestinal toxicity of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol: Histopathological analysis. Toxicol. Vitr. 2009, 23, 1580–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Li, X.; Lin, Q.; Shen, Z.; Feng, J.; Hu, C. Resveratrol Improves Intestinal Morphology and Anti-Oxidation Ability in Deoxynivalenol-Challenged Piglets. Animals 2022, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, S.; Sun, N.; Li, H.; Khan, A.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Y.; Fan, R. Deoxynivalenol damages the intestinal barrier and biota of the broiler chickens. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, F.; Armstrong, C.; Nera, E.; Truelove, J.; Fernie, S.; Scott, P.; Stapley, R.; Hayward, S.; Gunner, S. Chronic feeding study of deoxynivalenol in B6C3F1 male and female mice. Teratog. Carcinog. Mutagen. 1995, 15, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracarense, A.-P.F.L.; Lucioli, J.; Grenier, B.; Pacheco, G.D.; Moll, W.-D.; Schatzmayr, G.; Oswald, I.P. Chronic ingestion of deoxynivalenol and fumonisin, alone or in interaction, induces morphological and immunological changes in the intestine of piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1776–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluske, J.R.; Turpin, D.L.; Kim, J.-C. Gastrointestinal tract (gut) health in the young pig. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masada, M.P.; Persson, R.G.; Kenney, J.S.; Lee, S.W.; Page, R.C.; Allison, A.C. Measurement of interleukin-1α and -1β in gingival crevicular fluid: Implications for the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 1990, 25, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-C.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Cao, L.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Chen, X.-F.; Chu, X.-Y.; Zhu, D.-F.; Rahman, S.U.; Feng, S.-B.; et al. Deoxynivalenol Induces Intestinal Damage and Inflammatory Response through the Nuclear Factor-κB Signaling Pathway in Piglets. Toxins 2019, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.M.; Cory, S. The Bcl-2 Protein Family: Arbiters of Cell Survival. Science 1998, 281, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.F.; Li, R.N.; Dai, P.Y.; Li, Z.J.; Li, Y.S.; Li, C.M. Deoxynivalenol induced apoptosis and inflammation of IPEC-J2 cells by promoting ROS production. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lin, Z. Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) alleviated sepsis-induced acute liver injury, inflammation, oxidative stress and cell apoptosis by downregulating CUL3 expression. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 2459–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, N.; Seo, S.-U.; Chen, G.Y.; Nunez, G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, H.; Payros, D.; Pinton, P.; Theodorou, V.; Mercier-Bonin, M.; Oswald, I.P. Impact of mycotoxins on the intestine: Are mucus and microbiota new targets? J. Toxicol. Environ. Health-Part B-Crit. Rev. 2017, 20, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Willer, T.; Li, L.; Pielsticker, C.; Rychlik, I.; Velge, P.; Kaspers, B.; Rautenschlein, S. Influence of the Gut Microbiota Composition on Campylobacter jejuni Colonization in Chickens. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00380-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J. The Effects of Deoxynivalenol on the Ultrastructure of the Sacculus Rotundus and Vermiform Appendix, as Well as the Intestinal Microbiota of Weaned Rabbits. Toxins 2020, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.E.; Jeong, J.Y.; Song, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, D.-W.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, M.; Oh, Y.K.; et al. Colon Microbiome of Pigs Fed Diet Contaminated with Commercial Purified Deoxynivalenol and Zearalenone. Toxins 2018, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajarillo, E.A.B.; Chae, J.P.; Balolong, M.P.; Kim, H.B.; Seo, K.-S.; Kang, D.-K. Pyrosequencing-based Analysis of Fecal Microbial Communities in Three Purebred Pig Lines. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Hehemann, J.-H.; Rebuffet, E.; Czjzek, M.; Michel, G. Environmental and gut Bacteroidetes: The food connection. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, I.A.; Aroniadis, O.C.; Kelly, L.; Brandt, L.J. Postinfection Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Links Between Gastroenteritis, Inflammation, the Microbiome, and Functional Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 51, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, P.; Zhao, J.; Sun, J.; Guan, W.; Johnston, L.J.; Leyesque, C.L.; Fan, P.; He, T.; et al. Dietary Clostridium butyricum Induces a Phased Shift in Fecal Microbiota Structure and Increases the Acetic Acid-Producing Bacteria in a Weaned Piglet Model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5157–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, C. Effects of Adding Clostridium sp. WJ06 on Intestinal Morphology and Microbial Diversity of Growing Pigs Fed with Natural Deoxynivalenol Contaminated Wheat. Toxins 2017, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Cyr, M.J.; Perrin-Guyomard, A.; Houee, P.; Rolland, J.-G.; Laurentie, M. Evaluation of an Oral Subchronic Exposure of Deoxynivalenol on the Composition of Human Gut Microbiota in a Model of Human Microbiota-Associated Rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, G.T. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; He, S.; Xiong, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota-metabolic axis insight into the hyperlipidemic effect of lotus seed resistant starch in hyperlipidemic mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 314, 120939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wei, H.; Zhou, Y.; Szeto, C.-H.; Li, C.; Lin, Y.; Coker, O.O.; Lau, H.C.H.; Chan, A.W.H.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. High-Fat Diet Promotes Colorectal Tumorigenesis Through Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 135–149.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Kubota, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Tsugawa, H.; Suda, W.; Kwon, A.T.-J.; Yazaki, J.; Ikeda, K.; Nemoto, S.; Mochizuki, Y.; et al. Gut microbial carbohydrate metabolism contributes to insulin resistance. Nature 2023, 621, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber-Ruano, I.; Calvo, E.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Rodriguez-Pena, M.M.; Ceperuelo-Mallafre, V.; Cedo, L.; Nunez-Roa, C.; Miro-Blanch, J.; Arnoriaga-Rodriguez, M.; Balvay, A.; et al. Orally administered Odoribacter laneus improves glucose control and inflammatory profile in obese mice by depleting circulating succinate. Microbiome 2022, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiippala, K.; Barreto, G.; Burrello, C.; Diaz-Basabe, A.; Suutarinen, M.; Kainulainen, V.; Bowers, J.R.; Lemmer, D.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Eklund, K.K.; et al. Novel Odoribacter splanchnicus Strain and Its Outer Membrane Vesicles Exert Immunoregulatory Effects in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 575455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimzadeh, M.; Sadeghizadeh, M.; Najafi, F.; Arab, S.; Mobasheri, H. Impact of heat shock step on bacterial transformation efficiency. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2016, 5, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Item | CON Group | T1 Group | T2 Group | T3 Group | T4 Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac index | 6.12 ± 0.87 | 6.18 ± 0.62 | 5.70 ± 0.65 | 6.28 ± 1.22 | 5.84 ± 0.76 | 0.626 |

| Hepatic index | 41.77 ± 2.27 b | 46.84 ± 2.81 a | 43.86 ± 1.99 ab | 43.91 ± 1.89 ab | 43.49 ± 2.00 b | 0.002 |

| Renal index | 12.87 ± 2.52 | 13.35 ± 0.81 | 13.73 ± 0.56 | 13.85 ± 0.63 | 13.75 ± 0.61 | 0.534 |

| Spleen index | 3.01 ± 0.28 | 3.06 ± 0.17 | 3.08 ± 0.32 | 2.99 ± 0.24 | 3.12 ± 0.52 | 0.932 |

| Item | CON Group | T1 Group | T2 Group | T3 Group | T4 Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum GSH-Px (U/mL) | 1612.25 ± 57.09 a | 1315.19 ± 56.79 c | 1380.04 ± 41.55 c | 1485.45 ± 46.92 b | 1557.14 ± 56.55 ab | <0.001 |

| Liver GSH-Px (U/mg protein) | 816.56 ± 26.02 a | 625.09 ± 41.51 c | 713.82 ± 20.10 b | 720.87 ± 19.40 b | 796.79 ± 39.81 a | <0.001 |

| Serum SOD (U/mL) | 31.93 ± 1.64 a | 26.47 ± 0.62 c | 27.41 ± 1.16 c | 29.64 ± 2.17 b | 29.90 ± 0.88 ab | <0.001 |

| Liver SOD (U/mg protein) | 9.59 ± 0.82 a | 7.01 ± 0.72 b | 7.70 ± 0.57 b | 7.72 ± 0.59 b | 9.12 ± 0.56 a | <0.001 |

| Serum CAT (U/mL) | 29.80 ± 1.78 b | 26.47 ± 1.10 c | 25.67 ± 0.95 c | 42.12 ± 2.72 a | 28.43 ± 1.52 b | <0.001 |

| Liver CAT (U/mg protein) | 86.94 ± 7.36 a | 62.86 ± 6.83 d | 66.45 ± 5.21 cd | 73.01 ± 7.61 bc | 81.18 ± 4.39 ab | <0.001 |

| Serum MDA (nmol/mL) | 10.85 ± 0.46 c | 23.27 ± 2.59 a | 13.55 ± 1.54 b | 14.68 ± 0.98 b | 11.15 ± 0.90 c | <0.001 |

| Liver MDA (nmol/mg protein) | 3.91 ± 0.55 b | 5.11 ± 0.95 a | 4.95 ± 0.72 ab | 5.07 ± 0.55 a | 4.27 ± 0.47 ab | 0.006 |

| Item | CON Group | T1 Group | T2 Group | T3 Group | T4 Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.10 ± 0.24 a | 3.50 ± 0.16 b | 3.52 ± 0.15 b | 3.78 ± 0.28 ab | 3.81 ± 0.23 ab | <0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.34 ± 0.13 b | 1.68 ± 0.12 a | 1.41 ± 0.12 b | 1.53 ± 0.11 ab | 1.34 ± 0.18 b | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.61 ± 0.29 a | 1.62 ± 0.19 b | 1.75 ± 0.37 b | 1.91 ± 0.25 b | 1.97 ± 0.37 b | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.87 ± 0.53 b | 4.78 ± 0.65 a | 4.45 ± 0.25 ab | 4.03 ± 0.31 b | 3.89 ± 0.58 b | 0.004 |

| Item | CON Group | T1 Group | T2 Group | T3 Group | T4 Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum ALT (U/L) | 6.93 ± 1.04 b | 13.44 ± 1.42 a | 7.99 ± 0.23 b | 8.26 ± 0.64 b | 7.52 ± 1.03 b | <0.001 |

| Hepatic ALT (U/mg prot) | 2.87 ± 0.07 d | 4.12 ± 0.37 a | 2.11 ± 0.24 b | 3.20 ± 0.60 bc | 2.59 ± 0.12 cd | <0.001 |

| Serum AST (U/L) | 7.83 ± 0.68 b | 12.24 ± 0.78 a | 11.61 ± 0.78 a | 10.60 ± 1.57 a | 7.53 ± 2.04 b | <0.001 |

| Hepatic AST (U/mg prot) | 2.57 ± 0.42 b | 3.55 ± 0.47 a | 2.99 ± 0.15 b | 3.09 ± 0.44 ab | 2.93 ± 0.12 b | <0.001 |

| Serum AKP (King units/100 mL) | 9.15 ± 2.03 c | 18.06 ± 1.30 a | 13.10 ± 1.30 b | 10.99 ± 0.93 bc | 10.54 ± 1.13 c | <0.001 |

| Hepatic AKP (King units/mg prot) | 7.11 ± 0.55 d | 14.91 ± 1.41 a | 13.63 ± 0.47 b | 13.54 ± 0.60 b | 10.82 ± 0.40 c | <0.001 |

| ALB (g/L) | 31.33 ± 1.71 a | 27.86 ± 1.42 c | 29.08 ± 0.96 bc | 28.88 ± 1.49 bc | 30.63 ± 0.50 ab | <0.001 |

| CRE (μmol/L) | 16.43 ± 0.75 b | 29.22 ± 3.64 a | 27.79 ± 2.71 a | 25.04 ± 3.28 a | 17.17 ± 1.69 b | <0.001 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 4.94 ± 0.66 c | 8.31 ± 0.79 a | 7.56 ± 1.21 ab | 6.27 ± 0.99 bc | 5.65 ± 1.21 c | <0.001 |

| Item | CON Group | T1 Group | T2 Group | T3 Group | T4 Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villus Height (μm) | 393.40 ± 12.23 a | 280.39 ± 6.74 d | 320.54 ± 13.19 c | 322.60 ± 8.56 c | 353.74 ± 10.87 b | <0.001 |

| Crypt Depth (μm) | 95.54 ± 3.08 | 96.15 ± 4.44 | 100.43 ± 2.15 | 97.28 ± 2.69 | 96.90 ± 2.70 | 0.095 |

| Villus/Crypt Ratio | 4.12 ± 0.12 a | 2.92 ± 0.12 d | 3.19 ± 0.12 c | 3.32 ± 0.14 c | 3.65 ± 0.16 b | <0.001 |

| Gene | Primer Sequences (5′-3′) | Product Length (bp) | NCBI Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | F: ATATCGCTGCGCTGGTCG R: TTCCCACCATCACACCCTGG | 129 | NM_007393.5 |

| IL-1β | F: AATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTGATG R: AGCTTCTCCACAGCCACAAT | 189 | NM_008361.4 |

| IL-6 | F: TAGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC R: TTGGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTC | 76 | NM_031168.2 |

| TNF-α | F: GACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAGAG R: TTGGTGGTTTGTGAGTGTGAG | 228 | NM_013693.3 |

| ZO-1 | F: GCCGCTAAGAGCACAGCAA R: TCCCCACTCTGAAAATGAGGA | 134 | NM_001163574.2 |

| Occludin | F: TTGAAAGTCCACCTCCTTACAGA R: CCGGATAAAAAGAGTACGCTGG | 129 | NM_008756.2 |

| Claudin-1 | F: GGGGACAACATCGTGACCG R: AGGAGTCGAAGACTTTGCACT | 100 | NM_016674.4 |

| Bax | F: TGAAGACAGGGGCCTTTTTG R: AATTCGCCGGAGACACTCG | 140 | NM_007527.4 |

| Bcl-2 | F: GTCGCTACCGTCGTGACTTC R: CAGACATGCACCTACCCAGC | 284 | NM_177410.3 |

| Caspase-3 | F: GGGAGCAAGTCAGTGGACTC R: GCGAGATGACATTCCAGTGC | 126 | NM_001284409.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, H.; Xu, B.; Peng, Y.; Mao, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y. Heterologous Expression, Enzymatic Characterization, and Ameliorative Effects of a Deoxynivalenol (DON)-Degrading Enzyme in a DON-Induced Mouse Model. Toxins 2025, 17, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120588

Zhou H, Xu B, Peng Y, Mao J, Zhang X, Guo Y, Zhang Y. Heterologous Expression, Enzymatic Characterization, and Ameliorative Effects of a Deoxynivalenol (DON)-Degrading Enzyme in a DON-Induced Mouse Model. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120588

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Haorui, Bingtao Xu, Yuqing Peng, Jiahao Mao, Xuelei Zhang, Yongpeng Guo, and Yong Zhang. 2025. "Heterologous Expression, Enzymatic Characterization, and Ameliorative Effects of a Deoxynivalenol (DON)-Degrading Enzyme in a DON-Induced Mouse Model" Toxins 17, no. 12: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120588

APA StyleZhou, H., Xu, B., Peng, Y., Mao, J., Zhang, X., Guo, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Heterologous Expression, Enzymatic Characterization, and Ameliorative Effects of a Deoxynivalenol (DON)-Degrading Enzyme in a DON-Induced Mouse Model. Toxins, 17(12), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120588