Overcoming Analytical Challenges for the Detection of 27 Cyanopeptides Using a UHPLC-QqQ-MS Method in Fish Tissues

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Extraction Development in Muscle

2.1.1. Impact of Polypropylene Adsorption

2.1.2. Sonication Time

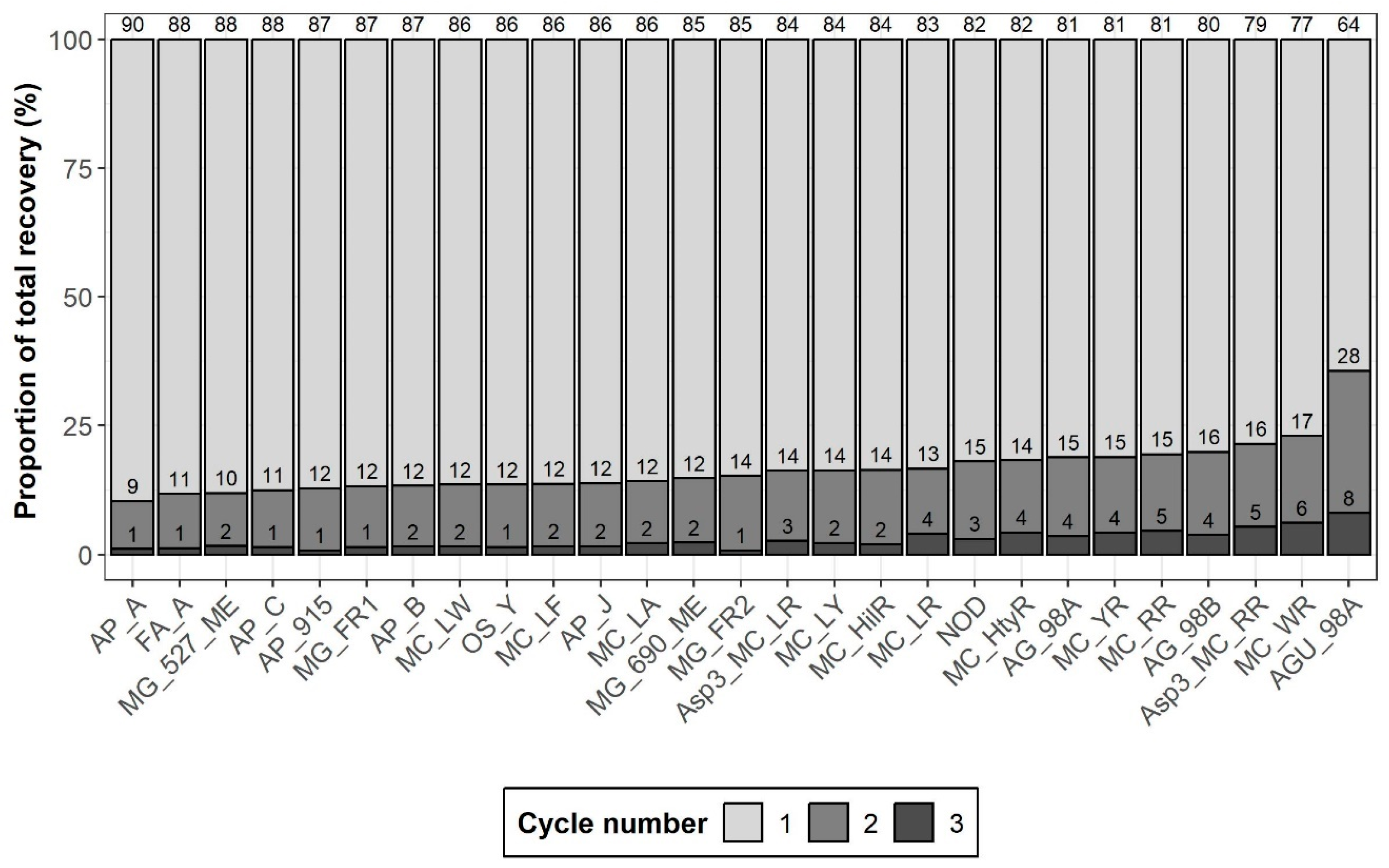

2.1.3. Extraction Cycle Number

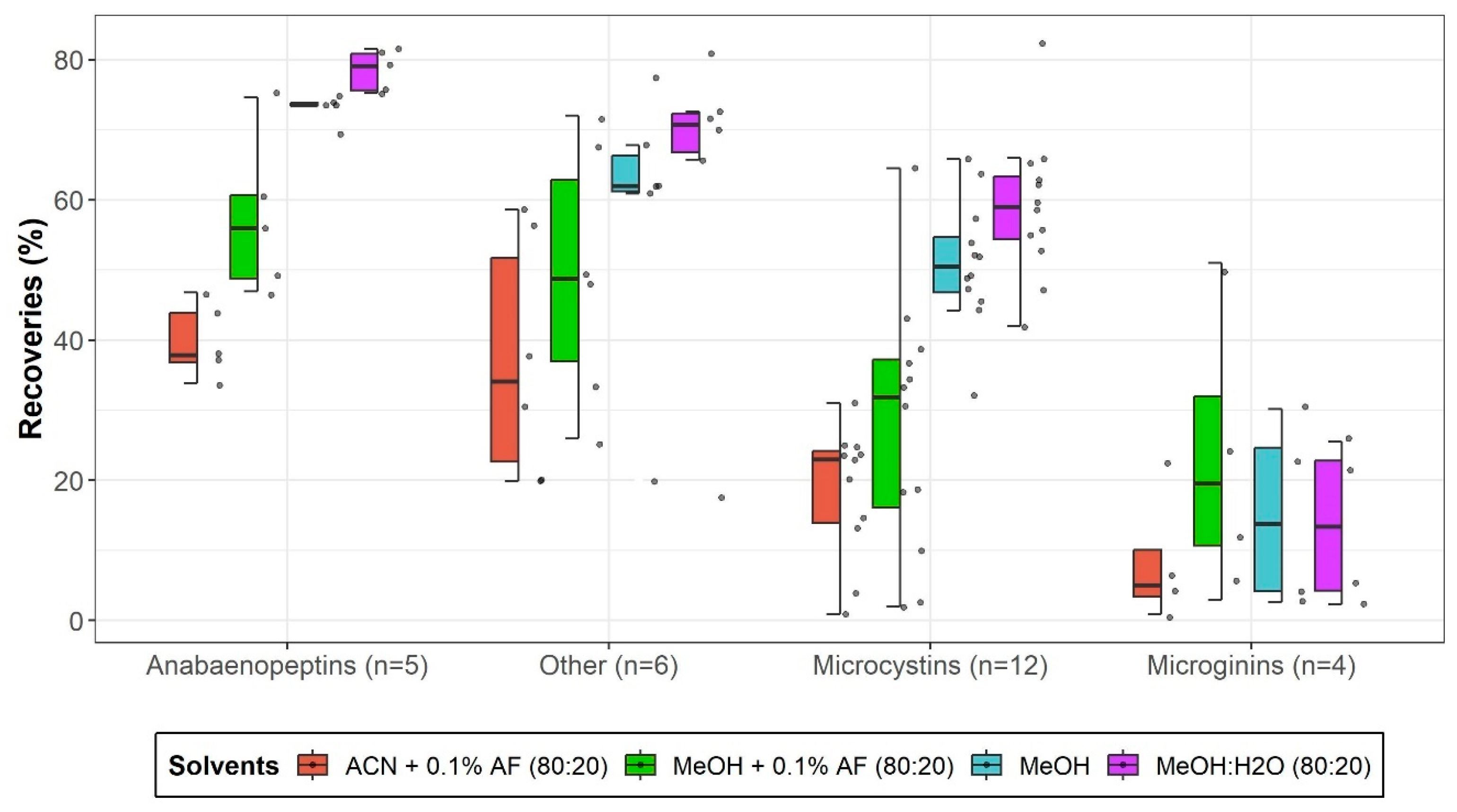

2.1.4. Liquid-Liquid Extraction Conditions Evaluation

2.1.5. Methanol Percentage in Sample

2.1.6. Filtration Step Prior to Analysis

2.2. Extraction Development in Liver

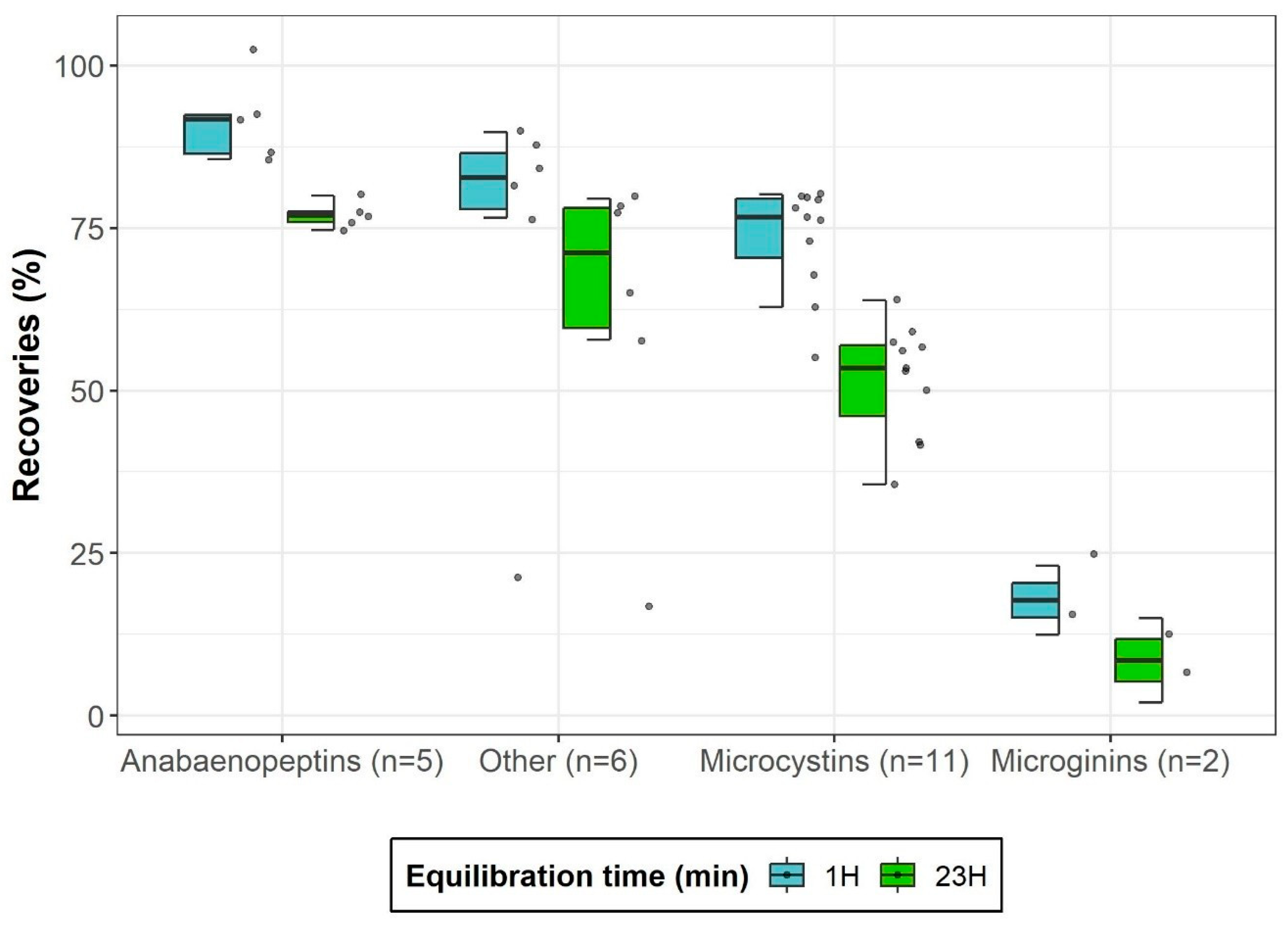

2.2.1. Optimization of Equilibration Time

2.2.2. Chromatographic Gradient Modifications

2.3. Validation

2.3.1. Recovery and Matrix Effects

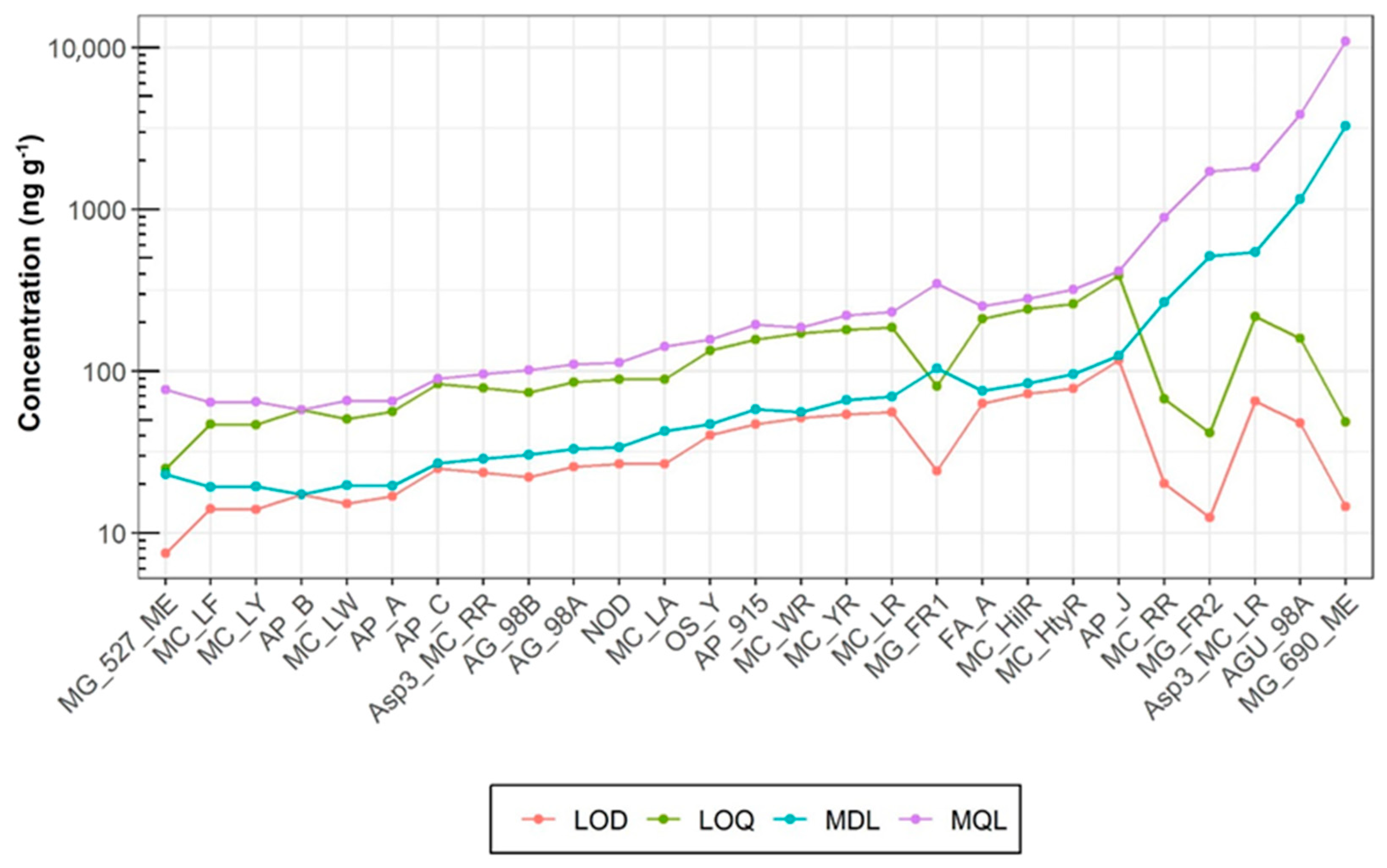

2.3.2. Precision, Accuracy, and Sensitivity

2.3.3. Microginins

2.4. Application in Environmental Samples

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Standard Solutions

4.2. Fish Samples

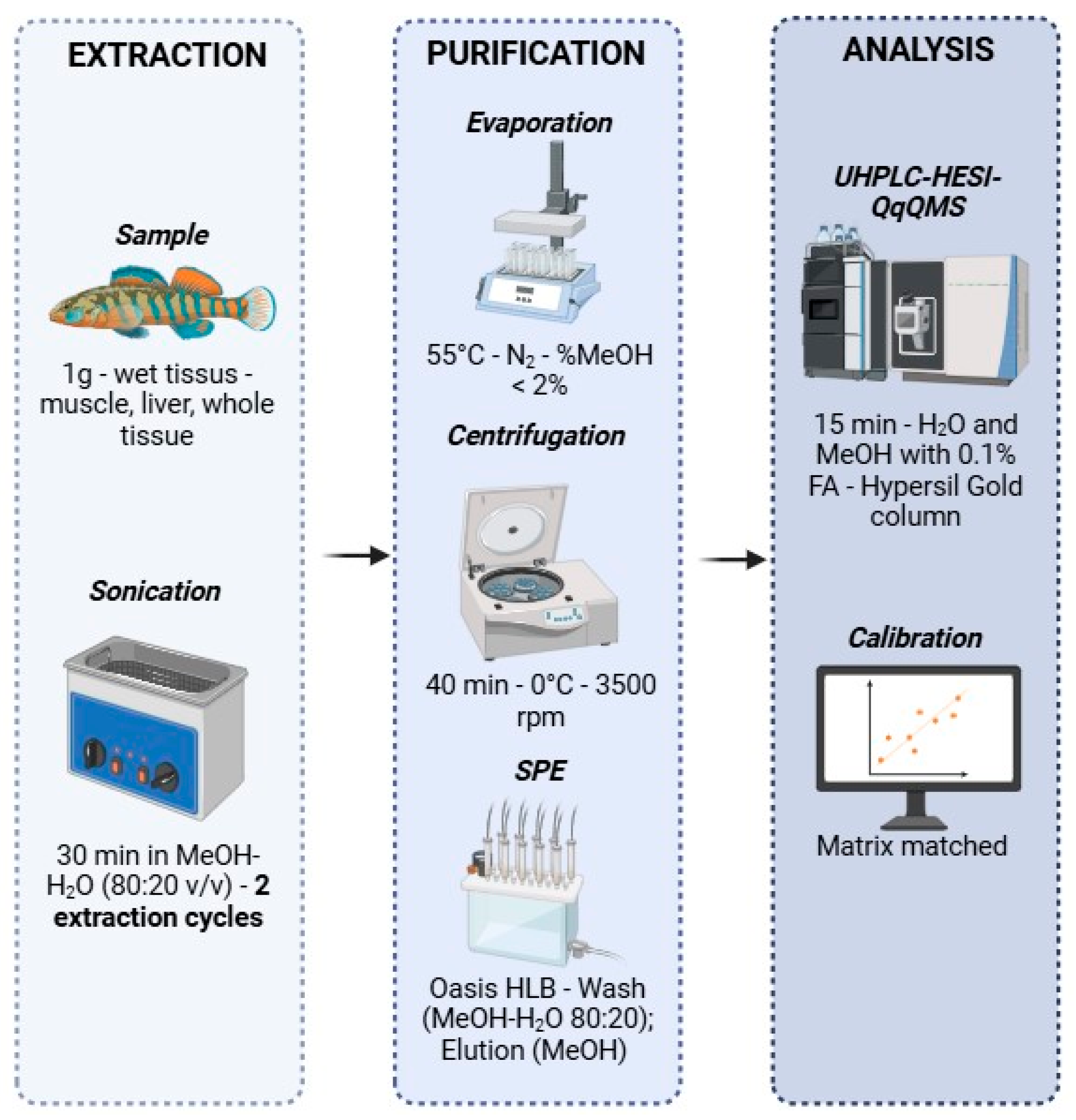

4.3. Extraction and Clean-Up

4.4. Ultra-High Liquid Chromatography-Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-QqQMS)

4.5. Method Validation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Adda | 3-Amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyl-deca-4,6-dienoic acid |

| MMPB | 2-Methyl-3-methoxy-4-phenylbutyric acid |

| MC | Microcystin |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| SPE | Solid-phase extraction |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| MG | Microginin |

| AGU | Aeruginoguanidine |

| AP | Anabaenopeptin |

| FA-A | Ferintoic acid A |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| logD | Distribution coefficient |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| GHP | Hydrophilic polypropylene |

| Mdha | N-methyldehydroalanine) |

| TR | Retention time |

| QC | Quality control |

| RSD | Relative standard deviations |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| MQL | Method limit of quantification |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MDL | Method limit of detection |

| FA | Formic acid |

| PETG | Polyethylene terephthalate glycol |

| UHPLC-QqQMS | Ultra-high liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry |

| HESI | Heated electrospray ionization |

| SRM | Selected reaction monitoring |

| CF | Correction factor |

References

- Chorus, I.; Fastner, J.; Welker, M. Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins in a Changing Environment: Concepts, Controversies, Challenges. Water 2021, 13, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Sommer, U. Effects of Harmful Blooms of Large-Sized and Colonial Cyanobacteria on Aquatic Food Webs. Water 2020, 12, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Akbar, S.; Sun, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, K.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z. Cyanobacterial Dominance and Succession: Factors, Mechanisms, Predictions, and Managements. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorus, I.; Welker, M. Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water: A Guide to Their Public Health Consequences, Monitoring and Management, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, E.M.-L. Cyanobacterial Peptides beyond Microcystins—A Review on Co-Occurrence, Toxicity, and Challenges for Risk Assessment. Water Res. 2019, 151, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Pinto, E.; Torres, M.A.; Dörr, F.; Mazur-Marzec, H.; Szubert, K.; Tartaglione, L.; Dell’Aversano, C.; Miles, C.O.; Beach, D.G.; et al. CyanoMetDB, a Comprehensive Public Database of Secondary Metabolites from Cyanobacteria. Water Res. 2021, 196, 117017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugumanova, G.; Ponomarev, E.D.; Askarova, S.; Fasler-Kan, E.; Barteneva, N.S. Freshwater Cyanobacterial Toxins, Cyanopeptides and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Toxins 2023, 15, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da S Ferrão-Filho, A.; Kozlowsky-Suzuki, B. Cyanotoxins: Bioaccumulation and Effects on Aquatic Animals. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 2729–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.; Gomes, A.; Calado, L.; Yasui, G.; Assis, D.; Henry, T.; Fonseca, A.; Pinto, E. Toxicity of Cyanopeptides from Two Microcystis Strains on Larval Development of Astyanax Altiparanae. Toxins 2019, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd, G.A.; Morrison, L.F.; Metcalf, J.S. Cyanobacterial Toxins: Risk Management for Health Protection. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 203, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, I.Y.; Yang, F.; Ding, Z.; Yang, S.; Guo, J.; Tezi, C.; Al-Osman, M.; Kamegni, R.B.; Zeng, W. Exposure Routes and Health Effects of Microcystins on Animals and Humans: A Mini-Review. Toxicon 2018, 151, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfushynska, H.; Kasianchuk, N.; Siemens, E.; Henao, E.; Rzymski, P. A Review of Common Cyanotoxins and Their Effects on Fish. Toxics 2023, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliu-Rodriguez, D.; Kucheriavaia, D.; Palagama, D.S.W.; Lad, A.; O’Neill, G.M.; Birbeck, J.A.; Kennedy, D.J.; Haller, S.T.; Westrick, J.A.; Isailovic, D. Development and Application of Extraction Methods for LC-MS Quantification of Microcystins in Liver Tissue. Toxins 2020, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaner, S.; Puddick, J.; Fessard, V.; Feurstein, D.; Zemskov, I.; Wittmann, V.; Dietrich, D.R. Simultaneous Detection of 14 Microcystin Congeners from Tissue Samples Using UPLC- ESI-MS/MS and Two Different Deuterated Synthetic Microcystins as Internal Standards. Toxins 2019, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geis-Asteggiante, L.; Lehotay, S.J.; Fortis, L.L.; Paoli, G.; Wijey, C.; Heinzen, H. Development and Validation of a Rapid Method for Microcystins in Fish and Comparing LC-MS/MS Results with ELISA. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 2617–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Boyer, G.L. Standardization of Microcystin Extraction from Fish Tissues: A Novel Internal Standard as a Surrogate for Polar and Non-Polar Variants. Toxicon 2009, 53, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, B.; Maul, R.; Campbell, K.; Elliott, C.T. Detection of Freshwater Cyanotoxins and Measurement of Masked Microcystins in Tilapia from Southeast Asian Aquaculture Farms. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 4057–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadel-Six, S.; Moyenga, D.; Magny, S.; Trotereau, S.; Edery, M.; Krys, S. Detection of Free and Covalently Bound Microcystins in Different Tissues (Liver, Intestines, Gills, and Muscles) of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Method Characterization. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ye, J.; Zhang, R.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C. Detection of Free Microcystins in the Liver and Muscle of Freshwater Fish by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2017, 52, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manubolu, M.; Lee, J.; Riedl, K.M.; Kua, Z.X.; Collart, L.P.; Ludsin, S.A. Optimization of Extraction Methods for Quantification of Microcystin-LR and Microcystin-RR in Fish, Vegetable, and Soil Matrices Using UPLC–MS/MS. Harmful Algae 2018, 76, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skafi, M.; Vo Duy, S.; Munoz, G.; Dinh, Q.T.; Simon, D.F.; Juneau, P.; Sauvé, S. Occurrence of Microcystins, Anabaenopeptins and Other Cyanotoxins in Fish from a Freshwater Wildlife Reserve Impacted by Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms. Toxicon 2021, 194, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekebri, A.; Blondina, G.J.; Crane, D.B. Method Validation of Microcystins in Water and Tissue by Enhanced Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 3147–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, I.M.; Molina, R.; Jos, A.; Picó, Y.; Cameán, A.M. Determination of Microcystins in Fish by Solvent Extraction and Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1080, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xie, P.; Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Liang, G. Development and Validation of a Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay for the Simultaneous Quantitation of Microcystin-RR and Its Metabolites in Fish Liver. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Waack, J.; Lewis, A.; Edwards, C.; Lawton, L. Development and Single-Laboratory Validation of a UHPLC-MS/MS Method for Quantitation of Microcystins and Nodularin in Natural Water, Cyanobacteria, Shellfish and Algal Supplement Tablet Powders. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1074–1075, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Quijada Jiménez, L.; Guzmán-Guillén, R.; Cătunescu, G.M.; Campos, A.; Vasconcelos, V.; Jos, Á.; Cameán, A.M. A New Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Cyanotoxins (Microcystins and Cylindrospermopsin) in Mussels Using SPE-UPLC-MS/MS. Environ. Res. 2020, 185, 109284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msagati, T.; Siame, B.; Shushu, D. Evaluation of Methods for the Isolation, Detection and Quantification of Cyanobacterial Hepatotoxins. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 78, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaravadivelu, D.; Sanan, T.T.; Venkatapathy, R.; Mash, H.; Tettenhorst, D.; DAnglada, L.; Frey, S.; Tatters, A.O.; Lazorchak, J. Determination of Cyanotoxins and Prymnesins in Water, Fish Tissue, and Other Matrices: A Review. Toxins 2022, 14, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, F.; Ikai, Y.; Oka, H.; Okumura, M.; Ishikawa, N.; Harada, K.; Matsuura, K.; Murata, H.; Suzuki, M. Formation, Characterization, and Toxicity of the Glutathione and Cysteine Conjugates of Toxic Heptapeptide Microcystins. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992, 5, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaraki, M.T.; Shahmohamadloo, R.S.; Sibley, P.K.; MacPherson, K.; Bhavsar, S.P.; Simpson, A.J.; Ortiz Almirall, X. Optimization of an MMPB Lemieux Oxidation Method for the Quantitative Analysis of Microcystins in Fish Tissue by LC-QTOF MS. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, P.; Berry, J. Detection of Total Microcystin in Fish Tissues Based on Lemieux Oxidation and Recovery of 2-Methyl-3-Methoxy-4-Phenylbutanoic Acid (MMPB) by Solid-Phase Microextraction Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (SPME-GC/MS). Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2012, 92, 1443–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Lachapelle, A.; Solliec, M.; Sinotte, M.; Deblois, C.; Sauvé, S. Total Analysis of Microcystins in Fish Tissue Using Laser Thermal Desorption–Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LDTD-APCI-HRMS). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7440–7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, L.; Church, J.L.; Carpino, J.; Faltin-Mara, E.; Rubio, F. The Effects of Water Sample Treatment, Preparation, and Storage Prior to Cyanotoxin Analysis for Cylindrospermopsin, Microcystin and Saxitoxin. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 246, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaner, S.; Puddick, J.; Wood, S.; Dietrich, D. Adsorption of Ten Microcystin Congeners to Common Laboratory-Ware Is Solvent and Surface Dependent. Toxins 2017, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, S.P.; Bobbitt, J.M.; Taylor, R.B.; Lovin, L.M.; Conkle, J.L.; Chambliss, C.K.; Brooks, B.W. Determination of Microcystins, Nodularin, Anatoxin-a, Cylindrospermopsin, and Saxitoxin in Water and Fish Tissue Using Isotope Dilution Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1599, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; De La Cruz, A.A.; Rein, K.; O’Shea, K.E. Ultrasonically Induced Degradation of Microcystin-LR and -RR: Identification of Products, Effect of PH, Formation and Destruction of Peroxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 3941–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, X.; Korenkova, E.; Jobst, K.J.; MacPherson, K.A.; Reiner, E.J. A High Throughput Targeted and Non-Targeted Method for the Analysis of Microcystins and Anatoxin-A Using on-Line Solid Phase Extraction Coupled to Liquid Chromatography–Quadrupole Time-of-Flight High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 4959–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Lachapelle, A.; Duy, S.V.; Munoz, G.; Dinh, Q.T.; Bahl, E.; Simon, D.F.; Sauvé, S. Analysis of Multiclass Cyanotoxins (Microcystins, Anabaenopeptins, Cylindrospermopsin and Anatoxins) in Lake Waters Using on-Line SPE Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 5289–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.R.; Vasconcelos, V.M.; Antunes, A. Computational Study of the Covalent Bonding of Microcystins to Cysteine Residues—A Reaction Involved in the Inhibition of the PPP Family of Protein Phosphatases. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Schulz, K.L.; Zimba, P.V.; Boyer, G.L. Possible Mechanism for the Foodweb Transfer of Covalently Bound Microcystins. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteiller, P.; Biré, R.; Foss, A.J.; Guérin, T.; Lance, E. Analysis of Total Microcystins by Lemieux Oxidation and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry in Fish and Mussels Tissues: Optimization and Comparison of Protocols. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesley, T.M. Ion Suppression in Mass Spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 1041–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C.M. Affinity of Amphiphilic Molecules to Air/Water Surface. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 47928–47937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Lachapelle, A.; Solliec, M.; Gagnon, C. Characterizing Cyanopeptides and Transformation Products in Freshwater: Integrating Targeted, Suspect, and Non-Targeted Analysis with in Silico Modeling. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 4829–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roy-Lachapelle, A.; Teysseire, F.-X.; Gagnon, C. Overcoming Analytical Challenges for the Detection of 27 Cyanopeptides Using a UHPLC-QqQ-MS Method in Fish Tissues. Toxins 2025, 17, 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120580

Roy-Lachapelle A, Teysseire F-X, Gagnon C. Overcoming Analytical Challenges for the Detection of 27 Cyanopeptides Using a UHPLC-QqQ-MS Method in Fish Tissues. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):580. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120580

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoy-Lachapelle, Audrey, François-Xavier Teysseire, and Christian Gagnon. 2025. "Overcoming Analytical Challenges for the Detection of 27 Cyanopeptides Using a UHPLC-QqQ-MS Method in Fish Tissues" Toxins 17, no. 12: 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120580

APA StyleRoy-Lachapelle, A., Teysseire, F.-X., & Gagnon, C. (2025). Overcoming Analytical Challenges for the Detection of 27 Cyanopeptides Using a UHPLC-QqQ-MS Method in Fish Tissues. Toxins, 17(12), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120580