Cosmetic Treatment Using Botulinum Toxin in the Oral and Maxillofacial Area: A Narrative Review of Esthetic Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Studies in the English language;

- Include dosage of BoNT and/or number of injection points;

- Be performed in human adults with no diseases;

- Given BoNT injection of the face for cosmetic or esthetic purpose;

- The literature is limited to expert consensus.

- Studies using BoNT for other reasons than cosmetic/aesthetic: i.e., stroke, neurogenic, bladder management, spasticity, sialorrhea, bruxism, strabismus, myofascial pain, TMJ, or obesity;

- Studies using BoNT for cosmetic/aesthetic reasons in other parts of the body or other reasons: i.e., skin texture, scar, androgenic alopecia, neck wrinkles, trapezius hypertrophy, or calf hypertrophy;

- Studies that investigated only a single muscle.

3. Results

3.1. Cosmetic Indications and Contraindications

3.2. Cosmetically Used Botulinum Toxin Products

3.3. Facial Target Muscles and Injection Doses

3.4. Injection Techniques of BoNT in the Face

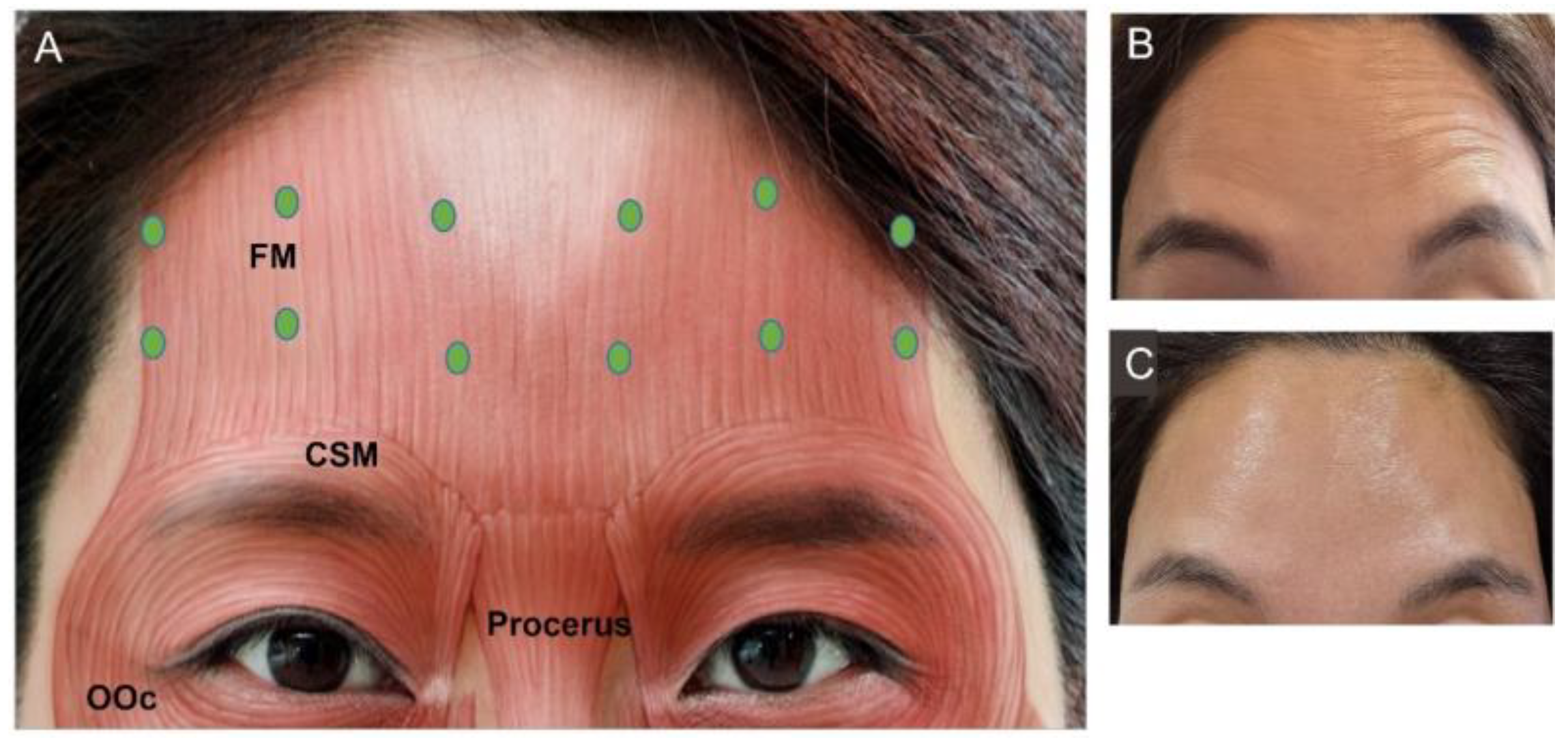

3.4.1. Forehead Frontalis

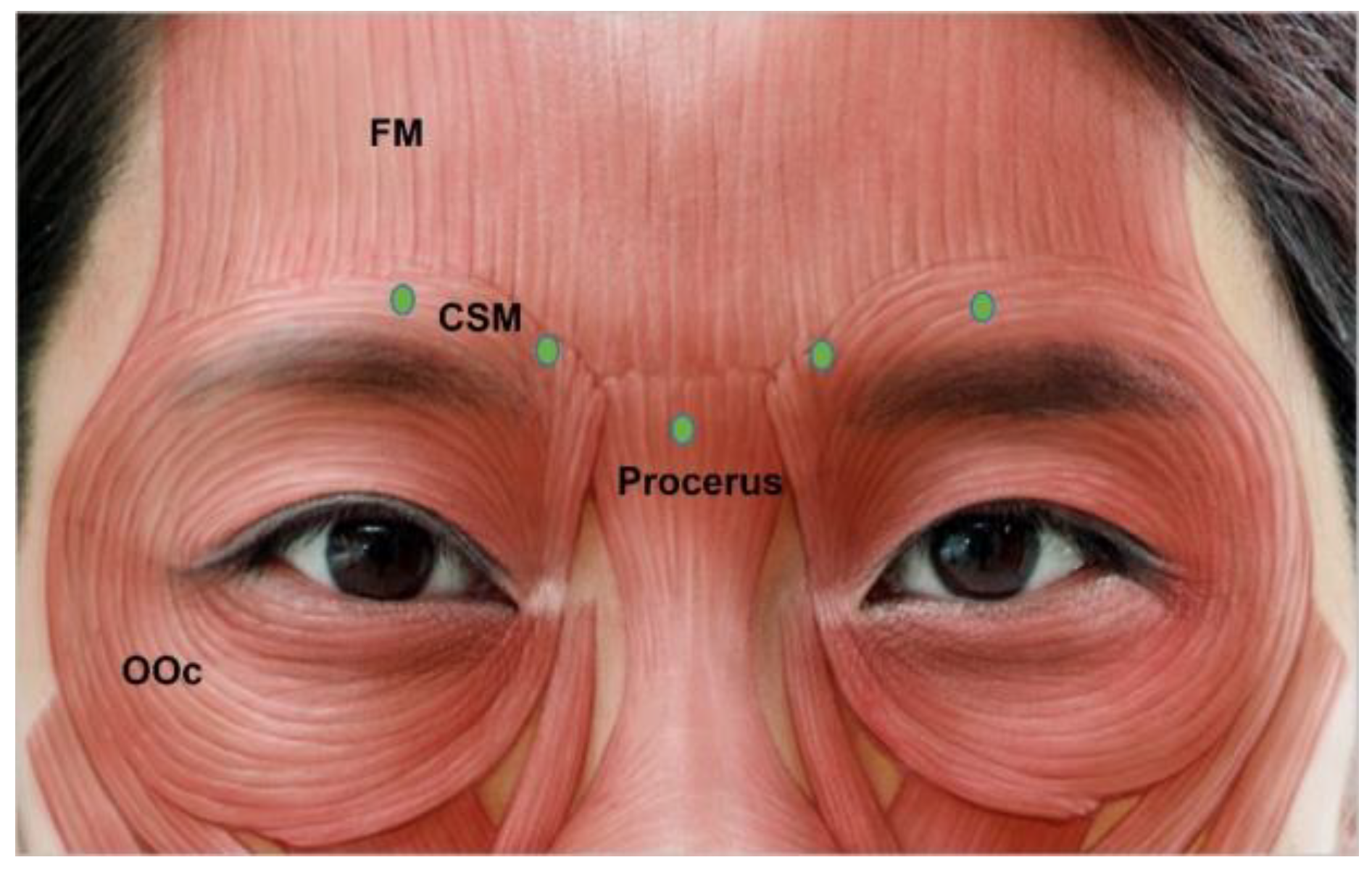

3.4.2. Glabella

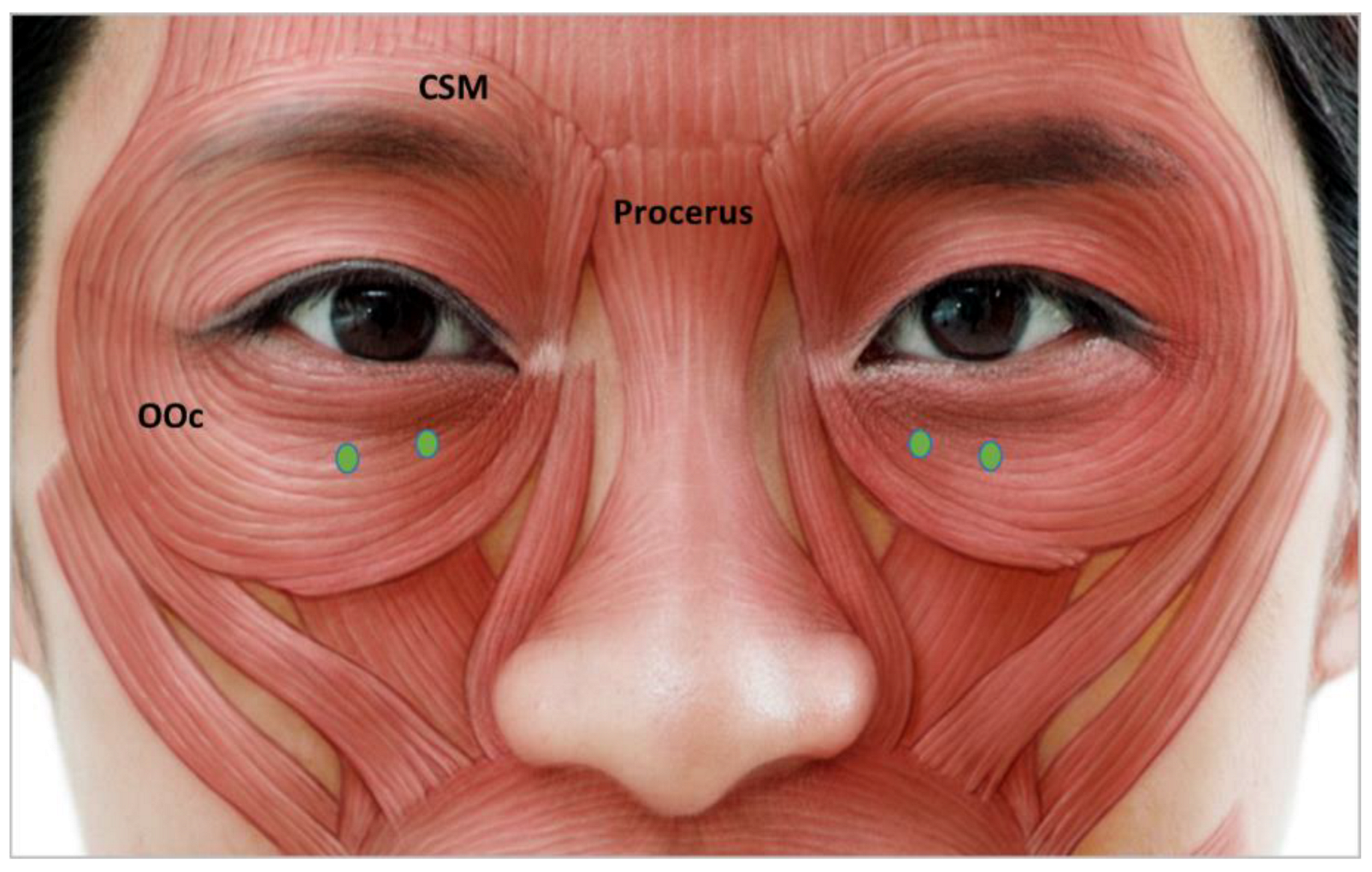

3.4.3. Lateral Canthal Lines (Crow’s Feet)

3.4.4. Infraorbital Rhytides

3.4.5. Bunny Lines

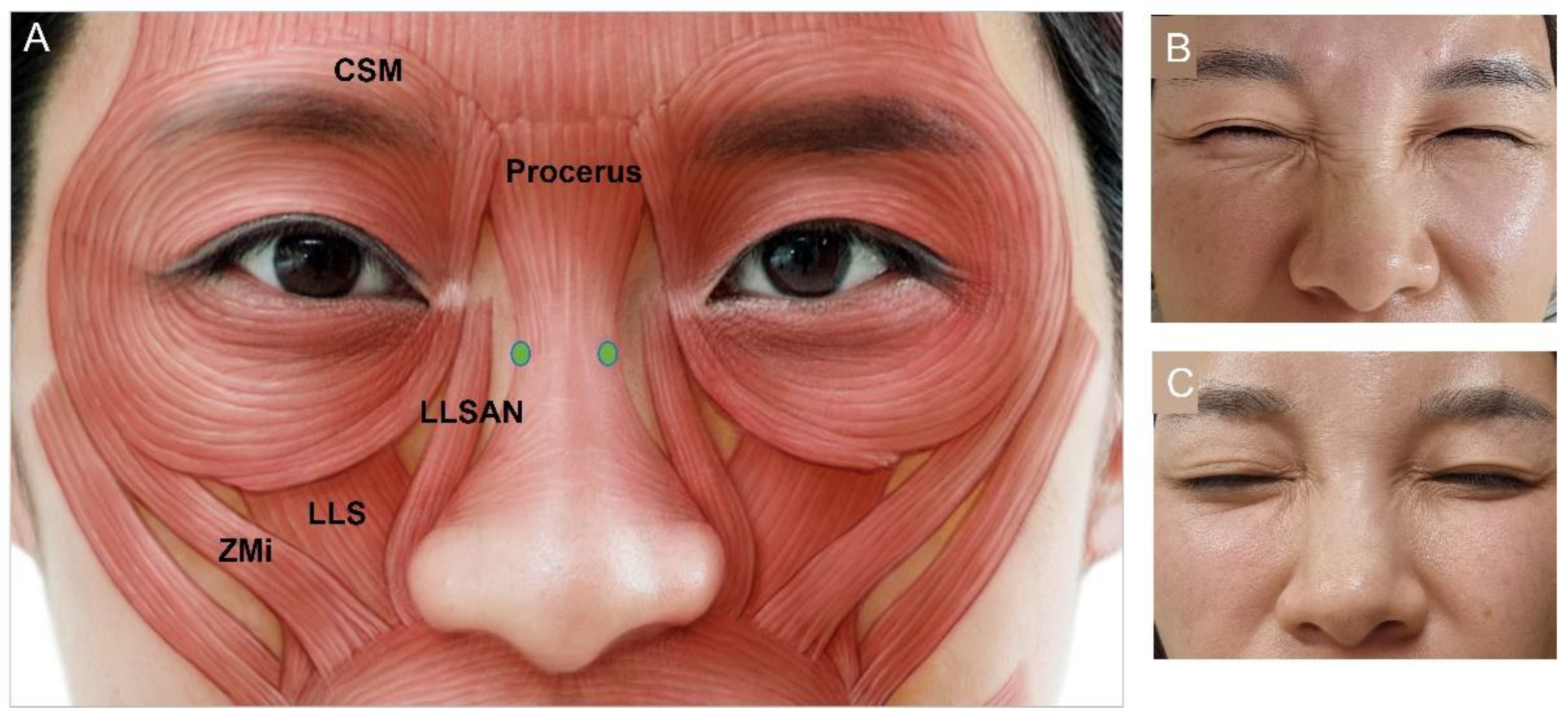

3.4.6. Gummy Smile

3.4.7. Perioral Rhytides

3.4.8. Masseter Hypertrophy

3.4.9. Parotid Gland Hypertrophy

3.4.10. Drooping Oral Commissures

3.4.11. Cobble Stone Chin

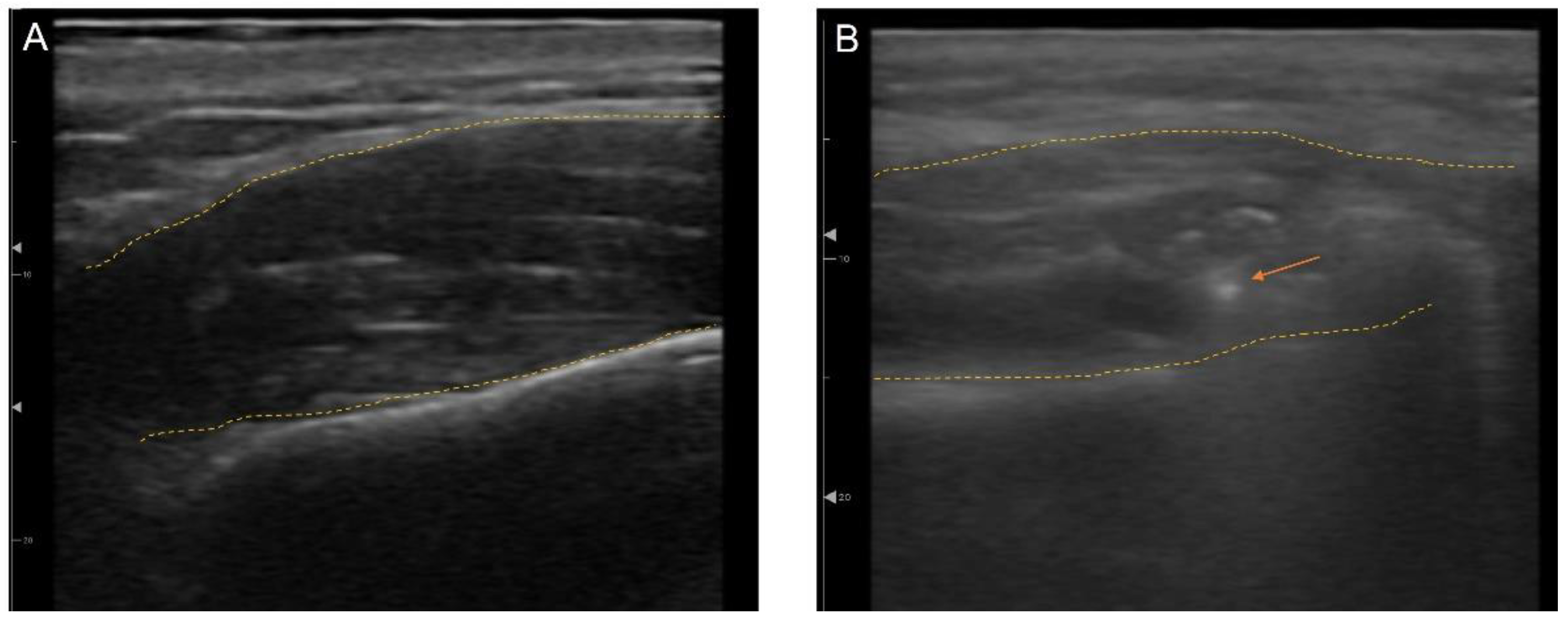

3.5. Ultrasonography (US)-Guided Botulinum Toxin Techniques

3.6. Complications

4. Discussion

5. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Adverse effects |

| BoNT | Botulinum toxin |

| CSM | Corrugator supercilia muscle |

| DAO | Depressor anguli oris |

| DLI | Depressor labii inferioris |

| FM | Frontalis muscle |

| HAS | Human Serum Albumin |

| IM | Intramuscularly |

| U | International Unit |

| IV | Intravenously |

| L | Liquid |

| LLS | Levator labii superioris |

| LLSAN | Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi |

| NACL | Sodium chloride |

| NAPs | Neurotoxin-associated complexing proteins |

| OOc | Orbicularis oculi |

| OOr | Orbicularis oris |

| P | Powder |

| PO | Orally |

| q.s. | Quantum sufficit |

| US | Ultrasonography |

| Zmi | Zygomaticus minor |

| ZMj | Zygomaticus major |

| IP | Injection points |

| n | Number |

| F | Female |

| M | Male |

| Up | Upper |

| L | Lower |

| NR | Not reported |

References

- Liew, S.; Dart, A. Nonsurgical reshaping of the lower face. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2008, 28, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, A.; Remington, K. BeautiPHIcation™: A global approach to facial beauty. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2011, 38, 347–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, S.; Wu, W.T.; Chan, H.H.; Ho, W.W.; Kim, H.J.; Goodman, G.J.; Peng, P.H.; Rogers, J.D. Consensus on changing trends, attitudes, and concepts of Asian beauty. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2016, 40, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, R. Botulinum toxin injection for facial wrinkles. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 90, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zimbler, M.S.; Kokoska, M.S.; Thomas, J.R. Anatomy and pathophysiology of facial aging. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 9, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gadhia, K.; Walmsley, A.D. Facial aesthetics: Is botulinum toxin treatment effective and safe? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 207, E9; discussion 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, K.; Younessi, S.; Dubin, D.; Lin, M.J.; Khorasani, H. Emerging off-label esthetic uses of botulinum toxin in dermatology. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frevert, J. Pharmaceutical, biological, and clinical properties of botulinum neurotoxin type A products. Drugs R D 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alster, T.S.; Harrison, I.S. Alternative clinical indications of botulinum toxin. Am. J. Clin. Derm. 2020, 21, 855–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrera-Figallo, M.A.; Ruiz-de-León-Hernández, G.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Castro-Araya, A.; Torres-Ferrerosa, O.; Hernández-Pacheco, E.; Gutierrez-Perez, J.L. Use of Botulinum Toxin in Orofacial Clinical Practice. Toxins 2020, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J. Botulinum toxin: State of the art. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benecke, R. Clinical relevance of botulinum toxin immunogenicity. BioDrugs 2012, 26, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, S.S.; Schechter, R.; Inglesby, T.V.; Henderson, D.A.; Bartlett, J.G.; Ascher, M.S.; Eitzen, E.; Fine, A.D.; Hauer, J.; Layton, M.; et al. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: Medical and public health management. JAMA 2001, 285, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, R.L.; Bigalke, H.; Dressler, D. Pharmacology of botulinum toxin: Differences between type A preparations. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006, 13 (Suppl. S1), 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, S.; Baker, M.R.; Chatterjee, S.; Kumar, H. Botulinum Toxin: An Update on Pharmacology and Newer Products in Development. Toxins 2021, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Masuyer, G.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Lundin, D.; Henriksson, L.; Miyashita, S.I.; Martínez-Carranza, M.; Dong, M.; Stenmark, P. Identification and characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, A.; Carruthers, J. Botulinum toxin type A. J. Am. Acad. Derm. 2005, 53, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.K.; Sobel, J.; Chatham-Stephens, K.; Luquez, C. Clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of botulism, 2021. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2021, 70, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspers, G.W.; Pijpe, J.; Jansma, J. The use of botulinum toxin type A in cosmetic facial procedures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 40, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, K.H.; Shin, K.S.; Yeon, S.H.; Kwon, D.G. Application of botulinum toxin in maxillofacial field: Part I. Bruxism and square jaw. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 41, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.S.; Bergeron, L.; Yu, C.C.; Chen, P.K.; Chen, Y.R. Mandible changes evaluated by computed tomography following Botulinum Toxin A injections in square-faced patients. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2011, 35, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majid, O.W. Clinical use of botulinum toxins in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 39, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schantz, E.J.; Johnson, E.A. Properties and use of botulinum toxin and other microbial neurotoxins in medicine. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.B. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology 1980, 87, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, J.; Carruthers, A. Botulinum toxin in facial rejuvenation: An update. Derm. Clin. 2009, 27, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Lora, V.R.M.; Del Bel Cury, A.A.; Jabbari, B.; Lacković, Z. Botulinum toxin type A in dental medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Rho, N.K.; Kim, H.S. Consensus recommendations on the aesthetic usage of botulinum toxin type A in Asians. Derm. Surg. 2013, 39, 1843–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, H.; Huang, P.H.; Hsu, N.J.; Huh, C.H.; Wu, W.T.; Wu, Y.; Cassuto, D.; Kerscher, M.J.; Seo, K.K. Aesthetic applications of botulinum toxin A in Asians: An international, multidisciplinary, Pan-Asian consensus. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.M.; Chatrath, V.; Anand, C.; Shetty, R.; Chhabra, C.; Singh, K.; Vedamurthy, M.; Pai, J.; Sthalekar, B.; Sheth, R. Consensus recommendations for treatment strategies in Indians using botulinum toxin and Hyaluronic Acid fillers. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.T.; Liew, S.; Chan, H.H.; Ho, W.W.; Supapannachart, N.; Lee, H.K.; Prasetyo, A.; Yu, J.N.; Rogers, J.D. Consensus on current injectable treatment strategies in the Asian face. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2016, 40, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagien, S.; Raspaldo, H. Facial rejuvenation with botulinum neurotoxin: An anatomical and experiential perspective. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2007, 9 (Suppl. S1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertossi, D.; Cavallini, M.; Cirillo, P.; Piero Fundarò, S.; Quartucci, S.; Sciuto, C.; Tonini, D.; Trocchi, G.; Signorini, M. Italian consensus report on the aesthetic use of onabotulinum toxin A. J. Cosmet. Derm. 2018, 17, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, J.; Fagien, S.; Matarasso, S.L. Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type a in facial aesthetics. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 114 (Suppl. S6), 1s–22s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, J.D.A.; Glogau, R.G.; Blitzer, A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: Botulinum toxin type a, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies—Consensus recommendations. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121 (Suppl. S5), 5s–30s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, J.; Fournier, N.; Kerscher, M.; Ruiz-Avila, J.; Trindade de Almeida, A.R.; Kaeuper, G. The convergence of medicine and neurotoxins: A focus on botulinum toxin type A and its application in aesthetic medicine—A global, evidence-based botulinum toxin consensus education initiative: Part II: Incorporating botulinum toxin into aesthetic clinical practice. Dermatol. Surg. 2013, 39 Pt 2, 510–525. [Google Scholar]

- Raspaldo, H.; Gassia, V.; Niforos, F.R.; Michaud, T. Global, 3-dimensional approach to natural rejuvenation: Part 1—Recommendations for volume restoration and the periocular area. J. Cosmet. Derm. 2012, 11, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassia, V.; Raspaldo, H.; Niforos, F.R.; Michaud, T. Global 3-dimensional approach to natural rejuvenation: Recommendations for perioral, nose, and ear rejuvenation. J. Cosmet. Derm. 2013, 12, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspaldo, H.; Niforos, F.R.; Gassia, V.; Dallara, J.M.; Bellity, P.; Baspeyras, M.; Belhaouari, L.; Group, C. Lower-face and neck antiaging treatment and prevention using onabotulinumtoxin A: The 2010 multidisciplinary French consensus—Part 2. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2011, 10, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspaldo, H.; Baspeyras, M.; Bellity, P.; Dallara, J.M.; Gassia, V.; Niforos, F.R.; Belhaouari, L. Upper- and mid-face anti-aging treatment and prevention using onabotulinumtoxin A: The 2010 multidisciplinary French consensus—Part 1. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2011, 10, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, B.; Talarico, S.; Cassuto, D.; Escobar, S.; Hexsel, D.; Jaén, P.; Monheit, G.D.; Rzany, B.; Viel, M. International consensus recommendations on the aesthetic usage of botulinum toxin type A (Speywood Unit)—Part II: Wrinkles on the middle and lower face, neck and chest. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2010, 24, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Donofrio, L.; Ascher, B.; Hexsel, D.; Monheit, G.; Rzany, B.; Weiss, R. Expanding the use of neurotoxins in facial aesthetics: A consensus panel’s assessment and recommendations. J. Drugs Derm. 2010, 9 (Suppl. S1), s7–s22, quiz s23–s25. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher, B.; Talarico, S.; Cassuto, D.; Escobar, S.; Hexsel, D.; Jaén, P.; Monheit, G.D.; Rzany, B.; Viel, M. International consensus recommendations on the aesthetic usage of botulinum toxin type A (Speywood Unit)—Part I: Upper facial wrinkles. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2010, 24, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yutskovskaya, Y.; Gubanova, E.; Khrustaleva, I.; Atamanov, V.; Saybel, A.; Parsagashvili, E.; Dmitrieva, I.; Sanchez, E.; Lapatina, N.; Korolkova, T.; et al. IncobotulinumtoxinA in aesthetics: Russian multidisciplinary expert consensus recommendations. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Derm. 2015, 8, 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, C.; Kane, M.A.; Bucay, V.W.; Allen, S.; Applebaum, D.J.; Baumann, L.; Cox, S.E.; Few, J.W.; Joseph, J.H.; Lorenc, Z.P.; et al. Current aesthetic use of abobotulinumtoxinA in clinical practice: An evidence-based consensus review. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2012, 32 (Suppl. S1), 8s–29s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, M.; Podda, M.; Sommer, B. S1 guideline aesthetic botulinum toxin therapy. J. Dtsch. Derm. Ges. 2013, 11, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, Z.P.; Kenkel, J.M.; Fagien, S.; Hirmand, H.; Nestor, M.S.; Sclafani, A.P.; Sykes, J.M.; Waldorf, H.A. Consensus panel’s assessment and recommendations on the use of 3 botulinum toxin type A products in facial aesthetics. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2013, 33 (Suppl. S1), 35s–40s. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, H.; Signorini, M.; Liew, S.; Trindade de Almeida, A.R.; Wu, Y.; Vieira Braz, A.; Fagien, S.; Goodman, G.J.; Monheit, G.; Raspaldo, H. Global Aesthetics Consensus: Botulinum Toxin Type A—Evidence-Based Review, Emerging Concepts, and Consensus Recommendations for Aesthetic Use, Including Updates on Complications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 518e–529e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, H.; Liew, S.; Signorini, M.; Vieira Braz, A.; Fagien, S.; Swift, A.; De Boulle, K.L.; Raspaldo, H.; Trindade de Almeida, A.R.; Monheit, G. Global aesthetics consensus: Hyaluronic Acid billers and botulinum toxin type A-recommendations for combined treatment and optimizing outcomes in diverse patient populations. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 1410–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, M.; Swift, A.; Signorini, M.; Fagien, S. Facial assessment and injection guide for botulinum toxin and injectable Hyaluronic Acid fillers: Focus on the upper Face. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 265e–276e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, M.; DeBoulle, K.; Braz, A.; Rohrich, R.J. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum toxin and injectable Hyaluronic Acid fillers: Focus on the midface. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 540e–550e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, M.; Wu, W.T.L.; Goodman, G.J.; Monheit, G. Facial assessment and injection guide for botulinum toxin and injectable Hyaluronic Acid fillers: Focus on the lower face. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 393e–404e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminer, M.S.; Cox, S.E.; Fagien, S.; Kaufman, J.; Lupo, M.P.; Shamban, A. Re-examining the optimal use of neuromodulators and the changing landscape: A consensus panel update. J. Drugs Derm. 2020, 19, s5–s15. [Google Scholar]

- Signorini, M.; Piero Fundarò, S.; Bertossi, D.; Cavallini, M.; Cirillo, P.; Natuzzi, G.; Quartucci, S.; Sciuto, C.; Patalano, M.; Trocchi, G. OnabotulinumtoxinA from lines to facial reshaping: A new Italian consensus report. J. Cosmet. Derm. 2022, 21, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, C.P.; Xia, J.; Costa, C.S.; Gemperli, R.; Tatini, M.D.; Bulsara, M.K.; Riera, R. Botulinum toxin type A for facial wrinkles. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, 011301. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, L.E.; Connor, L.M.; Moradi, A.; Alghoul, M. Current use of cosmetic toxins to improve facial aesthetics. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 147, 644e–657e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Seo, K.K.; Lee, H.-K.; Kim, J. Clinical anatomy for botulinum toxin injection. In Clinical Anatomy of the Face for Filler and Botulinum Toxin Injection; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 55–92. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.W. Complications, adverse reactions, and insights with the use of botulinum toxin. Derm. Surg. 2003, 29, 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K.H.; Shin, K.S.; Yeon, S.H.; Kwon, D.G. Application of botulinum toxin in maxillofacial field: Part II. Wrinkle, intraoral ulcer, and cranio-maxillofacial pain. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 41, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzini, M.; Rossetto, O.; Eleopra, R.; Montecucco, C. Botulinum Neurotoxins: Biology, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Pharm. Rev. 2017, 69, 200–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frevert, J.; Ahn, K.Y.; Park, M.Y.; Sunga, O. Comparison of botulinum neurotoxin type A formulations in Asia. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solish, N.; Carruthers, J.; Kaufman, J.; Rubio, R.G.; Gross, T.M.; Gallagher, C.J. Overview of DaxibotulinumtoxinA for injection: A novel formulation of botulinum toxin type A. Drugs 2021, 81, 2091–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Fujinaga, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Ohyama, T.; Takeshi, K.; Moriishi, K.; Nakajima, H.; Inoue, K.; Oguma, K. Molecular composition of Clostridium botulinum type A progenitor toxins. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodnough, M.C.; Johnson, E.A. Stabilization of botulinum toxin type A during lyophilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 3426–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dover, J.S.; Monheit, G.; Greener, M.; Pickett, A. Botulinum toxin in aesthetic medicine: Myths and realities. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-J.; Youn, K.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, S.O.; Na, J. US applications in botulinum toxin injection procedures. In Ultrasonographic Anatomy of the Face and Neck for Minimally Invasive Procedures: An Anatomic Guideline for Ultrasonographic-Guided Procedures; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-J.; Youn, K.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, S.O.; Na, J. General US anatomy of the face and neck. In Ultrasonographic Anatomy of the Face and Neck for Minimally Invasive Procedures: An Anatomic Guideline for Ultrasonographic-Guided Procedures; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 25–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gart, M.S.; Gutowski, K.A. Overview of botulinum toxins for aesthetic uses. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2016, 43, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokich, V.O.; Kokich, V.G.; Kiyak, H.A. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: Asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 130, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.O.; Baek, S.H.; Choi, J.Y. Physical therapy for smile improvement after orthognathic Surgery. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, R.; Hexsel, D. Gummy smile and botulinum toxin: A new approach based on the gingival exposure area. J. Am. Acad. Derm. 2010, 63, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.S.; Hur, M.S.; Hu, K.S.; Song, W.C.; Koh, K.S.; Baik, H.S.; Kim, S.T.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.J. Surface anatomy of the lip elevator muscles for the treatment of gummy smile using botulinum toxin. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, N.; Kothari, R.; Shah, N.; Sandhu, S.; Tripathy, D.M.; Galadari, H.; Gold, M.H.; Goldman, M.P.; Kassir, M.; Schepler, H.; et al. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in masseter muscle hypertrophy for lower face contouring. J. Cosmet. Derm. 2022, 21, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroumpouzos, G.; Kassir, M.; Gupta, M.; Patil, A.; Goldust, M. Complications of botulinum toxin, A. An update review. J. Cosmet. Derm. 2021, 20, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Hong, S.O.; Kim, H.M.; Oh, W.; Kim, H.J. Positional deformation of the parotid gland: Application to minimally invasive procedures. Clin. Anat. 2022, 35, 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teymoortash, A.; Sommer, F.; Mandic, R.; Schulz, S.; Bette, M.; Aumüller, G.; Werner, J.A. Intraglandular application of botulinum toxin leads to structural and functional changes in rat acinar cells. Br. J. Pharm. 2007, 152, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ondo, W.G.; Hunter, C.; Moore, W. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of botulinum toxin B for sialorrhea in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2004, 62, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.E.; Gronseth, G.; Rosenfeld, J.; Barohn, R.J.; Dubinsky, R.; Simpson, C.B.; McVey, A.; Kittrell, P.P.; King, R.; Herbelin, L. Randomized double-blind study of botulinum toxin type B for sialorrhea in ALS patients. Muscle Nerve 2009, 39, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Youn, K.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, S.O.; Na, J. US Applications in filler injection procedures. In Ultrasonographic Anatomy of the Face and Neck for Minimally Invasive Procedures: An Anatomic Guideline for Ultrasonographic-Guided Procedures; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-J.; Youn, K.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, S.O.; Na, J. US applications in thread lifting procedures. In Ultrasonographic Anatomy of the Face and Neck for Minimally Invasive Procedures: An Anatomic Guideline for Ultrasonographic-Guided Procedures; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Youn, K.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.J. Ultras.sound-guided botulinum neurotoxin type A injection for correcting asymmetrical smiles. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2018, 38, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.H.; Favero, V.; Mah, J.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, S.T. Effect of botulinum toxin injection on asymmetric lower face with chin deviation. Toxins 2020, 12, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollina, U.; Konrad, H. Managing adverse events associated with botulinum toxin type A: A focus on cosmetic procedures. Am. J. Clin. Derm. 2005, 6, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargaran, D.; Zoller, F.; Zargaran, A.; Rahman, E.; Woollard, A.; Weyrich, T.; Mosahebi, A. Complications of cosmetic botulinum toxin A injections to the upper face: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, N.; Singh, S.; DeBoulle, K.; Rahman, E. A review of Complications due to the use of botulinum toxin A for cosmetic indications. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadari, H.; Galadari, I.; Smit, R.; Prygova, I.; Redaelli, A. Use of AbobotulinumtoxinA for cosmetic treatments in the neck, and middle and lower areas of the face: A systematic review. Toxins 2021, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Yang, W.; Lindo, P.; Singh, B.R. Type A botulinum neurotoxin complex proteins differentially modulate host response of neuronal cells. Toxicon 2014, 82, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.Y.; Park, E.S. Immunogenicity of botulinum toxin. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2022, 49, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, P.; Jansen, A.; Lee, J.I.; Moll, M.; Ringelstein, M.; Rosenthal, D.; Bigalke, H.; Aktas, O.; Hartung, H.P.; Hefter, H. High prevalence of neutralizing antibodies after long-term botulinum neurotoxin therapy. Neurology 2019, 92, e48–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Mao, C.; Lei, X.; Lee, E. Safety and Efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Crow’s Feet Lines in Chinese Subjects. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moers-Carpi, M.; Dirschka, T.; Feller-Heppt, G.; Hilton, S.; Hoffmann, K.; Philipp-Dormston, W.G.; Rütter, A.; Tan, K.; Chapman, M.A.; Fulford-Smith, A. A randomised, double-blind comparison of 20 units of onabotulinumtoxinA with 30 units of incobotulinumtoxinA for glabellar lines. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2012, 14, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascher, B.; Kestemont, P.; Boineau, D.; Bodokh, I.; Stein, A.; Heckmann, M.; Dendorfer, M.; Pavicic, T.; Volteau, M.; Tse, A.; et al. Liquid formulation of AbobotulinumtoxinA exhibits a favorable efficacy and safety profile in moderate to severe glabellar Lines: A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled trial. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2018, 38, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, A.; Carruthers, J. A single-center, dose-comparison, pilot study of botulinum neurotoxin type A in female patients with upper facial rhytids: Safety and efficacy. J. Am. Acad. Derm. 2009, 60, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerscher, M.; Rzany, B.; Prager, W.; Turnbull, C.; Trevidic, P.; Inglefield, C. Efficacy and safety of IncobotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Upper Facial Lines: Results From a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study. Derm. Surg. 2015, 41, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, H.I.; Jung, N.; Won, C.H.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, Y.W. Efficacy and safety of Prabotulinumtoxin A and Onabotulinumtoxin A for Crow’s feet: A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, split-face study. Derm. Surg. 2019, 45, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, J.; Carruthers, A.; Monheit, G.D.; Davis, P.G. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/ml smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation: Satisfaction and patient-reported outcomes. Dermatol. Surg. 2010, 36 (Suppl. S4), 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.L.; Dayan, S.H.; Cox, S.E.; Yalamanchili, R.; Tardie, G. OnabotulinumtoxinA dose-ranging study for hyperdynamic perioral lines. Derm. Surg. 2012, 38, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandhari, R.; Imran, A.; Sethi, N.; Rahman, E.; Mosahebi, A. Onabotulinumtoxin Type A Dosage for upper face expression lines in males: A systematic review of current recommendations. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2021, 41, 1439–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Indication | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forehead | Glabella | Crow’s Feet | Infraorbital | Bunny Lines | ||||||

| Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | |

| Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | ||||||

| Carruthers et al., 2004, 2008 [33,34] | F: 6–15 M: 6–15 | 4–8 | F: 10–30 M: 20–40 | 5–7 | F: 10–30 M: 20–30 | 2–5/side | NR | NR | 2–5 | 1/side |

| Carruthers et al., 2013 [35] | 5–15 | 4–10 | F: 10–50 M: 20–60 | 5–7 | 10–30 | 2–5/side | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Raspaldo et al., 2011 [38,39] | F: 10–20 M: 10–30 | 3–5 | 8–25 | 2–5 | 6–16/side | 3–4/side | 2–4 | 1–2/side | 4–8 | 1/side |

| 1–2 | 4–5 | 2–4 | 0.5–2 | 2–4 | ||||||

| Maas et al., 2012 [44] | 11.75 (range: 5–30) | 6 | 20 (range: 12–25) | 5 | 20 (range: 6–30) | 3/side | 4 (range: 1.5–8) | 1/side | 6 (range: 2–12) | 1/side |

| Imhof et al., 2013 [45] | F: 8 M: 12 | 4–6 | 20 | 5 | 4–6 | 3/side | 2 | 2/side | 2 | 1/side |

| 0.5–2 | 4 | 1–3 | 0.5 | 1 | ||||||

| Lorenc et al., 2013 [46] | F: 10–20 M: 20–40 | 4–6 | 20 (range: 10–40) | 5 | 8–16/side | 4/side | 1 (range: 0.5–2.5) | 1/side | NR | NR |

| Yuskovskaya et al., 2015 [43] | 10–20 | 4–8 | 20 | 6 | 12/side | 3/side | NR | NR | 4–8 | 1/side |

| 2–4 | 2–5 | 4 | 2–4 | |||||||

| Sundaram et al., 2016 [47,48] | 8–25 | 4–8 | 12–40 | 3–7 | 6–15/side | 1–5/side | 0.5–2/side | 1–3/side | 4–8,10 | 2–3 |

| 2–4 | 2–4 | 1–4 | 0.5–2 | 2–4 | ||||||

| De Maio et al., 2017 [49,50,51] | NR | 5–7 | NR | 5 | NR | 3/side | NR | 1/side | 4–6 | 2 or 3 |

| 2 | ||||||||||

| Kaminer et al., 2020 [52] | F: 2–20 M: 4–30 | 2–12 | F: 6–35 M: 8–40 | 3–8 | 6–20 | 2–6/side | NR | NR | 2–10 | 1–2/side |

| Signorini et al., 2022 [53] | 20 | 5–10 | 30 | 5–7 | 18 | 3/side | 1–2 | 1/side | 4–6 | 1/side |

| 2–4 | 6 | 6 | 0.5–1 | 2–3 | ||||||

| Authors | Indication | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perioral | Gummy Smile | Masseter Hypertrophy | Parotid Gland Hypertrophy | DAO | Cobble Stone Chin | |||||||

| Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | IP (n) | |

| Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | Dose per IP (U) | |||||||

| Carruthers et al., 2004, 2008 [33,34] | 4–5 | 2–6 | 2–4 | 1/side | 25–30/side | NR | NR | NR | 2–5 | 1/side | 4–5 | 1–2 |

| Carruthers et al., 2013 [35] | 4–6 | 2–6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1–15 | 1/side | 4–10 | 1–2 |

| 1–7.5 | ||||||||||||

| Raspaldo et al., 2011 [38,39] | Up: 2–5 L: 2–5 | Up: 2–4 L: 2–4 | 3–5/side | 1/side | 18–30/side | 1–5/side | NR | NR | 2–5/side | 1–2/side | 6–10 | 2 |

| ~1 | 1–2 | 6 | 1–2.5 | 3–5 | ||||||||

| Maas et al., 2012 [44] | 5 (range: 2–12) | Up: 4 L: 2 | 5 (range: 2–10) | 1/side | 32.5 (range: 20–60) | 3/side | NR | NR | 6 (range: 2–10) | 1/side | 5 (range: 3–10) | 2–3 |

| Imhof et al., 2013 [45] | 4 | Up: 4 L: 2 | NR | NR | 4–6 | 2 or 3 | NR | NR | 1–3 | 1/side | 6 (range: 2–8) | 2 |

| 2 | ||||||||||||

| Lorenc et al., 2013 [46] | 5 | 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 1/side | 4–5 | 2 |

| 2.5 | 2.5 | |||||||||||

| Yuskovskaya et al., 2015 [43] | Up: 4–6 | Up: 4 | NR | NR | 50 | 3/side | NR | NR | 6 | 1/side | 6 | 2 |

| 1–1.5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||

| Sundaram et al., 2016 [47,48] | 1–5 | 2–5 | 1–4, 8 | 1–2/side | 15–40 | 1–5/side | NR | NR | 2–4/side | 1–2/side | 4–10 | 1–4 |

| 0.5–1 | 0.5–2 | 5–15 | 2 | 2–3 | ||||||||

| De Maio et al., 2017 [49,50,51] | Up: 2–4 L: 2 | U: 2–4 L: 2 | 6–10 | 3–5 | 6–24/side | 3/side | NR | NR | 4–8 | 1/side | 4–8 | 1- 3 |

| 1 | 2 | 4–8 | 2–4 | 2.5 | ||||||||

| Kaminer et al., 2020 [52] | 2–10 | 2–8 | NR | NR | 5–35 | 2–6/side | NR | NR | 2–6 | 1–2/side | 2–10 | 1–4 |

| Signorini et al., 2022 [53] | 1–4 | Up: 2–4 | 6–10 | 3 | 25–50/side | 3–5/side | NR | NR | 4–8 | 1/side | 8–10 | 1–2 |

| 0.5–1 | 2 | 5–10 or 7–22 | 2–4 | 4–10 | ||||||||

| Indication | Authors | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al., 2013 [27] | Wu et al., 2016 [30] | Sundaram et al., 2016 [28] | Kapoor et al., 2017 [29] | |||||||||

| Total Dose (U) | Dose per IP (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | Dose per IP (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | Dose per IP (U) | IP (n) | Total Dose (U) | Dose per IP (U) | IP (n) | |

| Forehead rhytides | 6–13.5 | 1–1.5 | 6–9 | 5–12 | 1–4 | NR | 12–14 (range: 2–32) | 0.1–5 | 12 | F: 6–8 M: 10–12 | NR | 4–6 |

| Glabella | 8 | 4 | 3 | 12–20 | NR | 3–10 | 10–20 (range: 6–25) | 2–4 | 3–5 | 16–20 | NR | 5–7 |

| Crow’s feet | 14 | 2–3 | 3/side | 6–12/side | 1–4 | NR | 6–9 (range: 4–16)/side | 2–4 | 3–4/side | 8–12/side | NR | 3–4/side |

| Infraorbital rhytides | 1–2 | 0.5 | 2–4 | 4–6 | NR | NR | 1–2 | 0.5–1 | 2–3/side | n/a | NR | NR |

| Bunny lines | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4–6 | NR | NR | 3–4 | 0.5–5 | 2 | 2–4/side | 1–2 | 2 |

| Perioral rhytides | 0.8–1.2 | 0.2–0.3 | 4 | 2–8 | NR | NR | 2–3 (range: 1–8) | 0.5–1 | 2–6 | 2–4 | NR | Up: 4 L: 2 |

| Gummy smile | 4–6 | 2–3 | 1/side | 2–12 | NR | NR | 2–4 | 1–2 | 2 | 2–3/side | NR | 2 |

| Bulky jaw | 24–30/side | 8–10 | 3/side | 40–80 | NR | NR | 20–40 | 4–6 | 3–5/side | 15–30/side | NR | 3/side |

| Parotid gland hypertrophy | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 20–40/side | 4–6 | 4–6 | NR | NR | NR |

| DAO | 6–10 | 3–5 | 1/side | 4–6 | NR | NR | 2–4/side | 2–4 | 1/side | 2–3/side | NR | 1/side |

| Cobblestone chin | mild: 5 severe: 10 | 5 | mild: 1 severe: 2 | 4–8 | NR | NR | 8 (range: 2–16) | 2–4 | 1–2/side | 6–8 | NR | 1–2 |

| US FDA-Approved Generic Name | Active Substance | Excipient | Unit/ Vial | Stabilization (form) | Commercial Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OnabotulinumtoxinA | Complex (900 kDa) | HSA 0.5 mg, NaCl 0.9 mg | 100 | Vacuum-dried (P) | Botox®, Botox Cosmetic®, Vistabel®, Vistabex® |

| AbobotulinumtoxinA | Complex (500–900 kDa) | HSA 0.125 mg, Lactose 2.5 mg | 500 | Lyophilized (P) | Dysport®, Reloxin®, Azzalure® |

| IncobotulinumtoxinA | Complex-free (150 kDa) | HSA 1 mg, Sucrose 4.7 mg L-methionine (q.s.) | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | Xeomin® Bocouture® |

| LanbotulinumtoxinA | Complex (900 kDa) | Gelatin 5 mg, Dextran 25 mg, Sucrose 25 mg | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | BTXA®, Prosigne®, Lantox® |

| LetibotulinumtoxinA | Complex | HSA 0.5 mgNaCl 0.9 mg | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | Botulax®, Regenox®, Zentox® |

| PrabotulinumtoxinA | Complex (900 kDa) | HSA 0.5 mgNaCl 0.9 mg | 100 | Vacuum-dried (P) | Nabota®, Jeuveau®, Nuceiva® |

| N/A | Complex (940 kDa) | HSA 0.5 mgNaCl 0.9 mg | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | Meditoxin®, Neuronox® |

| N/A | Complex (900 kDa) | Gelatin 6 mg, Maltose 12 mg | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | Relatox® |

| N/A | Complex | Polysorbate | 25 | L | Innotox® |

| N/A | Complex-free (150 KDa) | Polysorbate 20 (q.s.) Sucrose 3 mg NaCl 0.9 mg | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | Coretox® |

| DaxibotulinumtoxinA | Purified toxin (150 kDa) | Peptide (RTP004) Polysorbate 20 sugar | 100 | Lyophilized (P) | DAXXIFY® |

| RimabotulinumtoxinB | Complex (700 kDa) | HSA 0.5 mg NaCl 5.844 mg Sodium succinate 1.621 mg | 5000 | L | Neurobloc®, Myobloc® |

| Facial Treatment Areas | Target Muscles | Total Dose | Dose per IP | Number of IP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forehead rhytides | Frontalis | 6–20 U | 0.5–1 U | 4–6/row (2 rows) |

| Glabella (Frown lines) | Corrugator supercilia, Procerus, Depressor supercilii | 12–30 U | 2–4 U | 3–5 |

| Crow’s feet (Lateral canthal lines) | Lateral orbicularis oculi | 4–16 U/side | 2–4 U | 3–4/side |

| Infraorbital rhytides | Orbicularis oculi | 2–4 U | 0.5–1 U | 2–3/side |

| Bunny lines (Nasal rhytides) | Nasalis (transverse) Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi | 3–4 U | 1.5–2 U | 2 |

| Perioral rhytides (lipstick lines, smoker’s lines) | Orbicularis oris | 2–3 U | 0.5 U | 4–6 |

| Gummy smile | Levator labii superioris, Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, Zygomaticus minor | 2–6 U | 1–2 U | 1–2/side |

| Bulky jaw | Masseter | 15–30 U/side | 5 U | 3–5/side |

| Hypertrophic parotid gland | Parotid gland | 20–40 U | 4–6 U | 4–6/side |

| Drooping oral commissures (frown lines, DAO) | Depressor anguli oris | 4–10 U | 2–5 U | 2 |

| Cobblestone chin | Mentalis | 8–10 U | 2–4 U | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, S.O. Cosmetic Treatment Using Botulinum Toxin in the Oral and Maxillofacial Area: A Narrative Review of Esthetic Techniques. Toxins 2023, 15, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15020082

Hong SO. Cosmetic Treatment Using Botulinum Toxin in the Oral and Maxillofacial Area: A Narrative Review of Esthetic Techniques. Toxins. 2023; 15(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15020082

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Sung Ok. 2023. "Cosmetic Treatment Using Botulinum Toxin in the Oral and Maxillofacial Area: A Narrative Review of Esthetic Techniques" Toxins 15, no. 2: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15020082

APA StyleHong, S. O. (2023). Cosmetic Treatment Using Botulinum Toxin in the Oral and Maxillofacial Area: A Narrative Review of Esthetic Techniques. Toxins, 15(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15020082