Towards Understanding the Function of Aegerolysins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aegerolysins

2.1. Fungal Aegerolysins from Basidiomycota—Agaricomycotina

2.1.1. Aegerolysins from Pleurotus ostreatus

2.1.2. Aegerolysins from Pleurotus eryngii

2.1.3. Aegerolysins from Agrocybe aegerita

2.1.4. Aegerolysins from Moniliophthora perniciosa

2.1.5. Aegerolysins from Lignosus rhinocerotis

2.2. Fungal Aegerolysins from Ascomycota—Eurotimycetes

2.2.1. Aegerolysins from Aspergillus fumigatus

2.2.2. Aegerolysins from Aspergillus niger

2.2.3. Aegerolysins from Aspergillus terreus

2.2.4. Aegerolysins from Aspergillus oryzae

2.3. Fungal Aegerolysins from Ascomycota—Sordariomycetes

2.3.1. Aegerolysins from Beauveria bassiana

2.3.2. Aegerolysins from Trichoderma atroviride

2.4. Fungal Aegerolysins from Ascomycota—Dothideomycetes

Aegerolysins from Alternaria gaisen

2.5. Bacterial Aegerolysins from Firmicutes

2.5.1. Aegerolysins from Bacillus thuringiensis

2.5.2. Aegerolysins from Clostridium bifermentans

2.6. Bacterial Aegerolysins from Proteobacteria

2.6.1. Aegerolysins from Alcaligenes faecalis

2.6.2. Aegerolysins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa

2.7. Aegerolysins from Insecta, Lepidoptera

Aegerolysins from Pseudoplusia includes

2.8. Aegerolysins from Virus, Ascoviridae

Aegerolysins from Trichoplusia ni ascovirus 2c (TnAV2c)

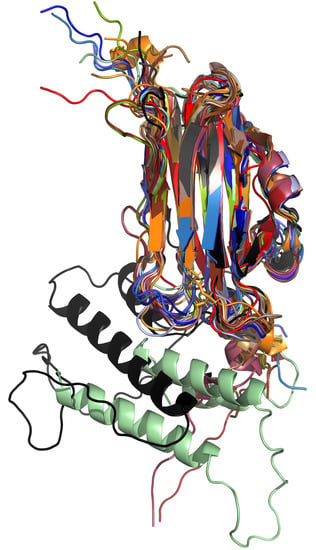

3. Sequences, Structures, and Structural Models of Aegerolysins

4. Aegerolysin Binary Partner Proteins

5. Lifestyle of Organisms Encoding for Aegerolysins and Putative Function of Aegerolysins

6. Conclusions and Future Research

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Literature Search

7.2. Comparative Genomics

7.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

7.4. Protein Structure Prediction

7.5. Protein Structure Presentation

7.6. Alignment of Proteins and Prediction of Secondary Structure

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berne, S.; Lah, L.; Sepčić, K. Aegerolysins: Structure, function, and putative biological role. Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butala, M.; Novak, M.; Kraševec, N.; Skočaj, M.; Veranič, P.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K. Aegerolysins: Lipid-binding proteins with versatile functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.P.; Green, B.J.; Beezhold, D.H. Fungal hemolysins. Med. Mycol. 2013, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, M.; Kraševec, N.; Skočaj, M.; Maček, P.; Anderluh, G.; Sepčić, K. Fungal aegerolysin-like proteins: Distribution, activities, and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, K.; Butala, M.; Viero, G.; Dalla Serra, M.; Sepčić, K.; Maček, P. Fungal MACPF-like proteins and aegerolysins: Bi-component pore-forming proteins? In Sub-Cellular Biochemistry; Anderluh, G., Gilbert, R., Eds.; Subcellular Biochemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 80, pp. 271–291. ISBN 978-94-017-8880-9. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji-Hasegawa, A.; Hullin-Matsuda, F.; Greimel, P.; Kobayashi, T. Pore-forming toxins: Properties, diversity, and uses as tools to image sphingomyelin and ceramide phosphoethanolamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T.; Ishitsuka, R.; Kobayashi, T. Detectors for evaluating the cellular landscape of sphingomyelin- and cholesterol-rich membrane domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2016, 1861, 812–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullin-Matsuda, F.; Makino, A.; Murate, M.; Kobayashi, T. Probing phosphoethanolamine-containing lipids in membranes with duramycin/cinnamycin and aegerolysin proteins. Biochimie 2016, 130, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullin-Matsuda, F.; Murate, M.; Kobayashi, T. Protein probes to visualize sphingomyelin and ceramide phosphoethanolamine. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2018, 216, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panevska, A.; Skočaj, M.; Modic, Š.; Razinger, J.; Sepčić, K. Aegerolysins from the fungal genus Pleurotus—Bioinsecticidal proteins with multiple potential applications. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 186, 107474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundner, M.; Panevska, A.; Sepčić, K.; Skočaj, M. What can mushroom proteins teach us about lipid rafts? Membranes 2021, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MycoCosm—The Fungal Genomics Resouce (DOE Joint Genome Institute). Available online: https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/home (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Ensembl Bacteria Release 54—Jul 2022 © EMBL-EBI. Available online: http://bacteria.ensembl.org/index.html (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Chang, H.-W.; Yang, C.-T.; Wali, N.; Shie, J.-J.; Hsueh, Y.-P. Sensory cilia as the Achilles heel of nematodes when attacked by carnivorous mushrooms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6014–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zervakis, G.I.; Ntougias, S.; Gargano, M.L.; Besi, M.I.; Polemis, E.; Typas, M.A.; Venturella, G. A reappraisal of the Pleurotus eryngii complex—New species and taxonomic combinations based on the application of a polyphasic approach, and an identification key to Pleurotus taxa associated with Apiaceae plants. Fungal Biol. 2014, 118, 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.K.; Rühl, M.; Mishra, B.; Kleofas, V.; Hofrichter, M.; Herzog, R.; Pecyna, M.J.; Sharma, R.; Kellner, H.; Hennicke, F.; et al. The genome sequence of the commercially cultivated mushroom Agrocybe aegerita reveals a conserved repertoire of fruiting-related genes and a versatile suite of biopolymer-degrading enzymes. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinhardt, L.W.; Rincones, J.; Bailey, B.A.; Aime, M.C.; Griffith, G.W.; Zhang, D.; Pereira, G.A.G. Moniliophthora perniciosa, the causal agent of witches’ broom disease of cacao: What’s new from this old foe? Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, S.-Y.; Tan, C.-S. Tiger milk mushroom (the Lignosus trinity) in Malaysia: A medicinal treasure trove. In Medicinal Mushrooms; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 349–369. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, R.P.; Riley, R.; Wiebenga, A.; Aguilar-Osorio, G.; Amillis, S.; Uchima, C.A.; Anderluh, G.; Asadollahi, M.; Askin, M.; Barry, K.; et al. Comparative genomics reveals high biological diversity and specific adaptations in the industrially and medically important fungal genus Aspergillus. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Azeem, A.M.; Salem, F.M.; Abdel-Azeem, M.A.; Nafady, N.A.; Mohesien, M.T.; Soliman, E.A. Biodiversity of the genus Aspergillus in different habitats. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nierman, W.C.; Pain, A.; Anderson, M.J.; Wortman, J.R.; Kim, H.S.; Arroyo, J.; Berriman, M.; Abe, K.; Archer, D.B.; Bermejo, C.; et al. Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 2005, 438, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, J.; Harvey, R.; Seaton, A. Sources and incidence of airborne Aspergillus fumigatus (Fres). Clin. Exp. Allergy 1976, 6, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, E.; Dunn-Coleman, N.; Frisvad, J.C.; Van Dijjck, P. On the safety of Aspergillus niger—A review. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 59, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, G.; Susca, A.; Cozzi, G.; Ehrlich, K.; Varga, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Meijer, M.; Noonim, P.; Mahakarnchanakul, W.; Samson, R.A. Biodiversity of Aspergillus species in some important agricultural products. Stud. Mycol. 2007, 59, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Safety Evaluation of Certain Mycotoxins in Food/Prepared by the Fifty-Sixth Meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA); Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pel, H.J.; de Winde, J.H.; Archer, D.B.; Dyer, P.S.; Hofmann, G.; Schaap, P.J.; Turner, G.; de Vries, R.P.; Albang, R.; Albermann, K.; et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of the versatile cell factory Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.P.; Blachere, F.M.; Hettick, J.M.; Lukomski, S.; Schmechel, D.; Beezhold, D.H. Characterization of recombinant terrelysin, a hemolysin of Aspergillus terreus. Mycopathologia 2011, 171, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, M.; Yamada, O.; Gomi, K. Genomics of Aspergillus oryzae: Learning from the history of koji mold and exploration of its future. DNA Res. 2008, 15, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, F.E.; Goettel, M.S.; Blackwell, M.; Chandler, D.; Jackson, M.A.; Keller, S.; Koike, M.; Maniania, N.K.; Monzón, A.; Ownley, B.H.; et al. Fungal entomopathogens: New insights on their ecology. Fungal Ecol. 2009, 2, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.; Vidkjær, N.H.; Hooshmand, K.; Jensen, B.; Fomsgaard, I.S.; Meyling, N.V. Seed inoculations with entomopathogenic fungi affect aphid populations coinciding with modulation of plant secondary metabolite profiles across plant families. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druzhinina, I.S.; Kubicek, C.P. Ecological Genomics of Trichoderma. In The Ecological Genomics of Fungi; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinina, I.S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Horwitz, B.A.; Kenerley, C.M.; Monte, E.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Zeilinger, S.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Kubicek, C.P. Trichoderma: The genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, L.; Le Crom, S.L.; Gruber, S.; Coulpier, F.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Kubicek, C.P.; Druzhinina, I.S. Comparative transcriptomics reveals different strategies of Trichodermamycoparasitism. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, L. Ecophysiology of Trichoderma in Genomic Perspective. In Biotechnology and Biology of Trichoderma; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.G.; Bischoff, J.F.; Reymond, S.T. Differential gene expression in Alternaria gaisen exposed to dark and light. Mycol. Prog. 2011, 11, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, E.G.; Roberts, R.G. Alternaria themes and variations (73). Mycotaxon 1993, 48, 109–140. [Google Scholar]

- Argôlo-Filho, R.; Loguercio, L. Bacillus thuringiensis is an environmental pathogen and host-specificity has developed as an adaptation to human-generated ecological niches. Insects 2013, 5, 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, L.; Muñoz, D.; Berry, C.; Murillo, J.; Caballero, P. Bacillus thuringiensis toxins: An overview of their biocidal activity. Toxins 2014, 6, 3296–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, N.; Chawla, S.; Likitvivatanavong, S.; Lee, H.L.; Gill, S.S. The Cry Toxin operon of Clostridium bifermentans subsp. malaysia is highly toxic to Aedes larval mosquitoes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5689–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ju, S.; Lin, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Sun, M. Alcaligenes faecalis ZD02, a Novel Nematicidal Bacterium with an Extracellular Serine Protease Virulence Factor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, B.B. Bacterial Disease in Diverse Hosts. Cell 1999, 96, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieda, Y.; Iiyama, K.; Yasunaga-Aoki, C.; Lee, J.M.; Kusakabe, T.; Shimizu, S. Pathogenicity of gacA mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 244, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.; Pereira, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa diversification during infection development in cystic fibrosis lungs—A review. Pathogens 2014, 3, 680–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, M.; Rahme, L.G. Modeling Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis in plant hosts. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, N.; Musarrat, J. Characterization of a new Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain NJ-15 as a potential biocontrol agent. Curr. Microbiol. 2003, 46, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, A.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Roque-Specht, V.F.; Valduga, E.; Gonzatti, F.; Schuh, S.M.; Carneiro, E. Biotic potential and life tables of Chrysodeixis includens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), Rachiplusia nu, and Trichoplusia ni on soybean and forage turnip. J. Insect Sci. 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Clark, K.D.; Strand, M.R. The protein P23 identifies capsule-forming plasmatocytes in the moth Pseudoplusia includens. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-W.; Wang, L.; Carner, G.R.; Arif, B.M. Characterization of three ascovirus isolates from cotton insects. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2005, 89, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xue, J.; Seaborn, C.P.; Arif, B.M.; Cheng, X.-W. Sequence and organization of the Trichoplusia ni ascovirus 2c (Ascoviridae) genome. Virology 2006, 354, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasiak, K.; Renault, S.; Federici, B.A.; Bigot, Y. Characteristics of pathogenic and mutualistic relationships of ascoviruses in field populations of parasitoid wasps. J. Insect Physiol. 2005, 51, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraševec, N.; Panevska, A.; Lemež, Š.; Razinger, J.; Sepčić, K.; Anderluh, G.; Podobnik, M. Lipid-Binding aegerolysin from biocontrol fungus Beauveria bassiana. Toxins 2021, 13, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, M.; Castanera, R.; Lavín, J.L.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Oguiza, J.A.; Ramírez, L.; Pisabarro, A.G. Comparative and transcriptional analysis of the predicted secretome in the lignocellulose-degrading basidiomycete fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 4710–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.; Salamov, A.A.; Brown, D.W.; Nagy, L.G.; Floudas, D.; Held, B.W.; Levasseur, A.; Lombard, V.; Morin, E.; Otillar, R.; et al. Extensive sampling of basidiomycete genomes demonstrates inadequacy of the white-rot/brown-rot paradigm for wood decay fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9923–9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanera, R.; López-Varas, L.; Borgognone, A.; LaButti, K.; Lapidus, A.; Schmutz, J.; Grimwood, J.; Pérez, G.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Grigoriev, I.V.; et al. Transposable elements versus the fungal genome: Impact on whole-genome architecture and transcriptional profiles. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkireddy, K.K.R.; Navarro-González, M.; Velagapudi, R.; Kües, U. Proteins expressed during hyphal aggregation for fruting body formation in basidiomycetes. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products, Arcachon, France, 4–7 October 2011; Savoie, J.-M., Foulongne-Oriol, M., Largeteau, M., Barroso, G., Eds.; Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA): Paris, France, 2011; pp. 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer, A.W.; Avigad, L.S. A cytolytic protein from the edible mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1979, 585, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kim, B.-G.; Kim, K.-J.; Lee, J.-S.; Yun, D.-W.; Hahn, J.-H.; Kim, G.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; Suh, D.-S.; Kwon, S.-T.; et al. Comparative analysis of sequences expressed during the liquid-cultured mycelia and fruit body stages of Pleurotus ostreatus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2002, 35, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, T.; Noguchi, K.; Mimuro, H.; Ukaji, F.; Ito, K.; Sugawara-Tomita, N.; Hashimoto, Y. Pleurotolysin, a novel sphingomyelin-specific two-component cytolysin from the edible mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus, assembles into a transmembrane pore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 26975–26982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoyanova, N.; Kondos, S.C.; Farabella, I.; Law, R.H.P.; Reboul, C.F.; Caradoc-Davies, T.T.; Spicer, B.A.; Kleifeld, O.; Traore, D.A.K.; Ekkel, S.M.; et al. Conformational changes during pore formation by the perforin-related protein pleurotolysin. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Voorspoels, A.; Versloot, R.C.A.; Van Der Heide, N.J.; Carlon, E.; Willems, K.; Maglia, G. PlyAB nanopores detect single amino acid differences in folded haemoglobin from blood. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202206227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Molecular Graphics System PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC). Available online: https://pymol.org/2/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Berne, S.; Križaj, I.; Pohleven, F.; Turk, T.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K. Pleurotus and Agrocybe hemolysins, new proteins hypothetically involved in fungal fruiting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1570, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maličev, E.; Chowdhury, H.H.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K. Effect of ostreolysin, an Asp-hemolysin isoform, on human chondrocytes and osteoblasts, and possible role of Asp-hemolysin in pathogenesis. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sepčić, K.; Berne, S.; Rebolj, K.; Batista, U.; Plemenitaš, A.; Šentjurc, M.; Maček, P. Ostreolysin, a pore-forming protein from the oyster mushroom, interacts specifically with membrane cholesterol-rich lipid domains. FEBS Lett. 2004, 575, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidic, I.; Berne, S.; Drobne, D.; Maček, P.; Frangež, R.; Turk, T.; Štrus, J.; Sepčić, K. Temporal and spatial expression of ostreolysin during development of the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebolj, K.; Sepčić, K. Ostreolysin, a cytolytic protein from culinary-medicinal oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.: Fr.) P. Kumm. (Agaricomycetideae), and its potential use in medicine and biotechnology. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2008, 10, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolj, K.; Bakrač, B.; Garvas, M.; Ota, K.; Šentjurc, M.; Potrich, C.; Coraiola, M.; Tomazzolli, R.; Serra, M.D.; Maček, P.; et al. EPR and FTIR studies reveal the importance of highly ordered sterol-enriched membrane domains for ostreolysin activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2010, 1798, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebolj, K.; Ulrih, N.P.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K. Steroid structural requirements for interaction of ostreolysin, a lipid-raft binding cytolysin, with lipid monolayers and bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chowdhury, H.H.; Rebolj, K.; Kreft, M.; Zorec, R.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K. Lysophospholipids prevent binding of a cytolytic protein ostreolysin to cholesterol-enriched membrane domains. Toxicon 2008, 51, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepčić, K.; Berne, S.; Potrich, C.; Turk, T.; Maček, P.; Menestrina, G. Interaction of ostreolysin, a cytolytic protein from the edible mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus, with lipid membranes and modulation by lysophospholipids. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003, 270, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, K.; Leonardi, A.; Mikelj, M.; Skočaj, M.; Wohlschlager, T.; Künzler, M.; Aebi, M.; Narat, M.; Križaj, I.; Anderluh, G.; et al. Membrane cholesterol and sphingomyelin, and ostreolysin A are obligatory for pore-formation by a MACPF/CDC-like pore-forming protein, pleurotolysin B. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endapally, S.; Frias, D.; Grzemska, M.; Gay, A.; Tomchick, D.R.; Radhakrishnan, A. Molecular discrimination between two conformations of sphingomyelin in plasma membranes. Cell 2019, 176, 1040–1053.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skočaj, M.; Resnik, N.; Grundner, M.; Ota, K.; Rojko, N.; Hodnik, V.; Anderluh, G.; Sobota, A.A.; Maček, P.; Veranič, P.; et al. Tracking cholesterol/sphingomyelin-rich membrane domains with the ostreolysin A-mCherry protein. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skočaj, M.; Yu, Y.; Grundner, M.; Resnik, N.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Leonardi, A.; Križaj, I.; Guella, G.; Maček, P.; Kreft Erdani, M.; et al. Characterisation of plasmalemmal shedding of vesicles induced by the cholesterol/sphingomyelin binding protein, ostreolysin A-mCherry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 2882–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, N.; Repnik, U.; Kreft, M.E.; Sepčić, K.; Maček, P.; Turk, B.; Veranič, P. Highly selective anti-cancer activity of cholesterol-interacting agents methyl-β-cyclodextrin and ostreolysin A/pleurotolysin B protein complex on urothelial cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panevska, A.; Skočaj, M.; Križaj, I.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K. Ceramide phosphoethanolamine, an enigmatic cellular membrane sphingolipid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2019, 1861, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milijaš Jotić, M.; Panevska, A.; Iacovache, I.; Kostanjšek, R.; Mravinec, M.; Skočaj, M.; Zuber, B.; Pavšič, A.; Razinger, J.; Modic, Š.; et al. Dissecting out the molecular mechanism of insecticidal activity of ostreolysin A6/pleurotolysin B complexes on western corn rootworm. Toxins 2021, 13, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panevska, A.; Hodnik, V.; Skočaj, M.; Novak, M.; Modic, Š.; Pavlic, I.; Podržaj, S.; Zarić, M.; Resnik, N.; Maček, P.; et al. Pore-forming protein complexes from Pleurotus mushrooms kill western corn rootworm and Colorado potato beetle through targeting membrane ceramide phosphoethanolamine. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, H.B.; Ishitsuka, R.; Inaba, T.; Murate, M.; Abe, M.; Makino, A.; Kohyama-Koganeya, A.; Nagao, K.; Kurahashi, A.; Kishimoto, T.; et al. Evaluation of aegerolysins as novel tools to detect and visualize ceramide phosphoethanolamine, a major sphingolipid in invertebrates. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 3920–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Krpan, T.; Panevska, A.; Shewell, L.K.; Day, C.J.; Jennings, M.P.; Guella, G.; Sepčić, K. Binding specificity of ostreolysin A6 towards Sf9 insect cell lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panevska, A.; Glavan, G.; Jemec Kokalj, A.; Kukuljan, V.; Trobec, T.; Žužek, M.C.M.C.; Vrecl, M.; Drobne, D.; Frangež, R.; Sepčić, K.; et al. Effects of bioinsecticidal aegerolysin-based cytolytic complexes on non-target organisms. Toxins 2021, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, N.; Grundner, M.; Ragucci, S.; Pavšič, M.; Mravinec, M.; Pedone, P.V.; Sepčić, K.; Di Maro, A. Characterization and cytotoxic activity of ribotoxin-like proteins from the edible mushroom Pleurotus eryngii. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntes, P.; Rebolj, K.; Sepčić, K.; Maček, P.; Cecilija Žužek, M.; Cestnik, V.; Frangež, R. Ostreolysin induces sustained contraction of porcine coronary arteries and endothelial dysfunction in middle- and large-sized vessels. Toxicon 2009, 54, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolj, K.; Batista, U.; Sepčić, K.; Cestnik, V.; Maček, P.; Frangež, R. Ostreolysin affects rat aorta ring tension and endothelial cell viability in vitro. Toxicon 2007, 49, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žužek, M.C.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K.; Cestnik, V.; Frangež, R. Toxic and lethal effects of ostreolysin, a cytolytic protein from edible oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), in rodents. Toxicon 2006, 48, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, T.; Trenti, F.; Panevska, A.; Bajc, G.; Guella, G.; Ciacci, C.; Canonico, B.; Canesi, L.; Sepčić, K. Ceramide aminoethylphosphonate as a new molecular target for pore-forming aegerolysin-based protein complexes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 902706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, L.; Spivak, O.; Tal, D.; Schälling, D.; Peri, I.; Graeve, L.; Salame, T.M.; Yarden, O.; Hadar, Y.; Schwartz, B. A recombinant fungal compound induces anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on colon cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28854–28864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, T.; Nimri, L.; Yehuda-Shnaidman, E.; Staikin, K.; Hadar, Y.; Friedler, A.; Amartely, H.; Slutzki, M.; Di Pizio, A.; Niv, M.Y.; et al. Recombinant ostreolysin induces brown fat-like phenotype in HIB-1B cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, L.; Staikin, K.; Peri, I.; Yehuda-Shnaidman, E.; Schwartz, B. Ostreolysin induces browning of adipocytes and ameliorates hepatic steatosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 33, 1990–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, M.; Čepin, U.; Hodnik, V.; Narat, M.; Jamnik, M.; Kraševec, N.; Sepčić, K.; Anderluh, G. Functional studies of aegerolysin and MACPF-like proteins in Aspergillus niger. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraševec, N.; Novak, M.; Barat, S.; Skočaj, M.; Sepčić, K.; Anderluh, G. Unconventional secretion of nigerolysins A from Aspergillus species. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, P.H.K.; Ng, T.B.B. A hemolysin from the mushroom Pleurotus eryngii. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, H.B.; Kishimoto, T.; Abe, M.; Makino, A.; Inaba, T.; Murate, M.; Dohmae, N.; Kurahashi, A.; Nishibori, K.; Fujimori, F.; et al. Binding of a pleurotolysin ortholog from Pleurotus eryngii to sphingomyelin and cholesterol-rich membrane domains. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2933–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurahashi, A.; Sato, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Nishibori, K.; Fujimori, F. Homologous genes, Pe.pleurotolysin A and Pe.ostreolysin, are both specifically and highly expressed in primordia and young fruiting bodies of Pleurotus eryngii. Mycoscience 2014, 55, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Kudou, M.; Hoshi, Y.; Kudo, A.; Nanashima, N.; Miyairi, K. Isolation and characterization of a novel two-component hemolysin, erylysin A and B, from an edible mushroom, Pleurotus eryngii. Toxicon 2010, 56, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, N.; Sepčić, K.; Plemenitaš, A.; Windoffer, R.; Leube, R.; Veranič, P. Desmosome assembly and cell-cell adhesion are membrane raft-dependent processes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundner, M.; Munjaković, H.; Tori, T.; Sepčić, K.; Gašperšič, R.; Oblak, Č.; Seme, K.; Guella, G.; Trenti, F.; Skočaj, M. Ceramide phosphoethanolamine as a possible marker of periodontal disease. Membranes 2022, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakihara, T.; Takiguchi, N.; Uzawa, H.; Serizawa, R.; Kobayashi, T. Erylysin A inhibits cytokinesis in Escherichia coli by binding with cardiolipin. J. Biochem. 2021, 170, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Espinar, M.T.; Labarere, J.; Labarère, J. Cloning and sequencing of the Aa-Pri1 gene specifically expressed during fruiting initiation in the edible mushroom Agrocybe aegerita, and analysis of the predicted amino-acid sequence. Curr. Genet. 1997, 32, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.B.L.; Gramacho, K.P.; Silva, D.C.; Góes-Neto, A.; Silva, M.M.; Muniz-Sobrinho, J.S.; Porto, R.F.; Villela-Dias, C.; Brendel, M.; Cascardo, J.C.M.; et al. Early development of Moniliophthora perniciosa basidiomata and developmentally regulated genes. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne, S.; Pohleven, J.; Vidic, I.; Rebolj, K.; Pohleven, F.; Turk, T.; Maček, P.; Sonnenberg, A.; Sepčić, K. Ostreolysin enhances fruiting initiation in the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 1431–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kües, U.; Liu, Y. Fruiting body production in basidiomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 54, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berne, S.; Sepčić, K.; Anderluh, G.; Turk, T.; Maček, P.; Poklar Ulrih, N. Effect of pH on the pore forming activity and conformational stability of ostreolysin, a lipid raft-binding protein from the edible mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 11137–11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, H.-Y.Y.; Fung, S.-Y.; Ng, S.-T.; Tan, C.-S.; Tan, N.-H. Genome-based proteomic analysis of Lignosus rhinocerotis (Cooke) Ryvarden sclerotium. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 12, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yap, H.-Y.Y.; Chooi, Y.-H.; Firdaus-Raih, M.; Fung, S.-Y.; Ng, S.-T.; Tan, C.-S.; Tan, N.-H. The genome of the tiger milk mushroom, Lignosus rhinocerotis, provides insights into the genetic basis of its medicinal properties. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, K.; Matsuda, A.; Wakabayashi, K.; Fununaga, N.; Fukunaga, N. Endotoxin-like substance from Aspergillus fumigatus. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 1962, 3, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, O.; Shimada, H.; Yokota, K. Proceedings: Purification and characteristics of hemolytic toxin from Aspergillus fumigatus. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 1975, 28, 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ebina, K.; Yokota, K.; Sakaguchi, O. Studies on toxin of Aspergillus fumigatus. XIV. Relationship between Asp-hemolysin and experimental infection for mice. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 1982, 23, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebina, K.; Sakagami, H.; Yokota, K.; Kondo, H. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of cDNA encoding Asp-hemolysin from Aspergillus fumigatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1219, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, Y.; Fukuchi, Y.; Kumagai, T.; Ebina, K.; Yokota, K. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein-binding specificity of Asp-hemolysin from Aspergillus fumigatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2001, 1568, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, T.; Nagata, T.; Kudo, Y.; Fukuchi, Y.; Ebina, K.; Yokota, K. Cytotoxic activity and cytokine gene induction of Asp-hemolysin to murine macrophages. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 1999, 40, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kumagai, T.; Nagata, T.; Kudo, Y.; Fukuchi, Y.; Ebina, K.; Yokota, K. Cytotoxic activity and cytokine gene induction of Asp-hemolysin to vascular endothelial cells. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 2001, 121, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wartenberg, D.; Lapp, K.; Jacobsen, I.D.; Dahse, H.-M.; Kniemeyer, O.; Heinekamp, T.; Brakhage, A.A. Secretome analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus reveals Asp-hemolysin as a major secreted protein. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 301, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rementeria, A.; López-Molina, N.; Ludwig, A.; Vivanco, A.B.; Bikandi, J.; Pontón, J.; Garaizar, J. Genes y moléculas implicados en la virulencia de Aspergillus fumigatus. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2005, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.P.; Green, B.J.; Janotka, E.; Hettick, J.M.; Friend, S.; Vesper, S.J.; Schmechel, D.; Beezhold, D.H. Monoclonal antibodies to hyphal exoantigens derived from the opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus terreus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 1568–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.P.; Green, B.J.; Friend, S.; Beezhold, D.H. Development of monoclonal antibodies to recombinant terrelysin and characterization of expression in Aspergillus terreus. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bando, H.; Hisada, H.; Ishida, H.; Hata, Y.; Katakura, Y.; Kondo, A. Isolation of a novel promoter for efficient protein expression by Aspergillus oryzae in solid-state culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisada, H.; Tsutsumi, H.; Ishida, H.; Hata, Y. High production of llama variable heavy-chain antibody fragment (VHH) fused to various reader proteins by Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, R.; Yoshie, T.; Wakai, S.; Asai-Nakashima, N.; Okazaki, F.; Ogino, C.; Hisada, H.; Tsutsumi, H.; Hata, Y.; Kondo, A. Aspergillus oryzae-based cell factory for direct kojic acid production from cellulose. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, J.; Vaknin, D.; Krebs, C.; Doroghazi, J.; Milam, S.L.; Balasubramanian, D.; Duck, N.B.; Freigang, J. Structure–function characterization of an insecticidal protein GNIP1Aa, a member of an MACPF and β-tripod families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2897–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, C.J.; Buckle, A.M.; Law, R.H.P.; Butcher, R.E.; Kan, W.-T.; Bird, C.H.; Ung, K.; Browne, K.A.; Baran, K.; Bashtannyk-Puhalovich, T.A.; et al. A common fold mediates vertebrate defense and bacterial attack. Science 2007, 317, 1548–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.S.; Bayly-Jones, C.; Radjainia, M.; Spicer, B.A.; Law, R.H.P.; Hodel, A.W.; Parsons, E.S.; Ekkel, S.M.; Conroy, P.J.; Ramm, G.; et al. The cryo-EM structure of the acid activatable pore-forming immune effector Macrophage-expressed gene 1. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, T.; Jiao, F.; Yu, X.; Aden, S.; Ginger, L.; Williams, S.I.; Bai, F.; Pražák, V.; Karia, D.; Stansfeld, P.; et al. Structure and mechanism of bactericidal mammalian perforin-2, an ancient agent of innate immunity. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Dehez, F.; Ni, T.; Yu, X.; Dittman, J.S.; Gilbert, R.; Chipot, C.; Scheuring, S. Perforin-2 clockwise hand-over-hand pre-pore to pore transition mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, B.A.; Law, R.H.P.; Caradoc-Davies, T.T.; Ekkel, S.M.; Bayly-Jones, C.; Pang, S.-S.; Conroy, P.J.; Ramm, G.; Radjainia, M.; Venugopal, H.; et al. The first transmembrane region of complement component-9 acts as a brake on its self-assembly. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, L.L.; Cooper, C.L.; Sodetz, J.M.; Lebioda, L. Structure of human C8 protein provides mechanistic insight into membrane pore formation by complement. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17585–17592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Karlsson, M. Functional characterization of the AGL1 aegerolysin in the mycoparasitic fungus Trichoderma atroviride reveals a role in conidiation and antagonism. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2021, 296, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigott, C.R.; Ellar, D.J. Role of receptors in Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin activity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelker, M.S.; Berry, C.; Evans, S.L.; Pai, R.; McCaskill, D.G.; Wang, N.X.; Russell, J.C.; Baker, M.D.; Yang, C.; Pflugrath, J.W.; et al. Structural and biophysical characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins Cry34Ab1 and Cry35Ab1. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, M.J.; Berry, C. Variants of theBacillus sphaericus binary toxins: Implications for differential toxicity of strains. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1998, 71, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narva, K.E.; Wang, N.X.; Herman, R. Safety considerations derived from Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1 structure and function. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 142, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, L.; Schwab, G.; Mazza, A.; Brousseau, R.; Potvin, L.; Schwartz, J.-L. A novel Bacillus thuringiensis (PS149B1) containing a Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1 binary toxin specific for the eestern corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte forms ion channels in lipid membranes. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 12349–12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moellenbeck, D.J.; Peters, M.L.; Bing, J.W.; Rouse, J.R.; Higgins, L.S.; Sims, L.; Nevshemal, T.; Marshall, L.; Ellis, R.T.; Bystrak, P.G.; et al. Insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis protect corn from corn rootworms. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Olson, M.; Lin, G.; Hey, T.; Tan, S.Y.; Narva, K.E. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1 interactions with western corn rootworm midgut membrane binding sites. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Eyun, S.; Arora, K.; Tan, S.; Gandra, P.; Moriyama, E.; Khajuria, C.; Jurzenski, J.; Li, H.; Donahue, M.; et al. Patterns of gene expression in western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera virgifera) neonates, challenged with Cry34Ab1, Cry35Ab1 and Cry34/35Ab1, based on next-generation sequencing. Toxins 2017, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, H.E.; Lee, S.; Dojillo, J.A.; Burmeister, P.; Fencil, K.; Morera, L.; Nygaard, L.; Narva, K.E.; Wolt, J.D. Characterization of Cry34/Cry35 binary insecticidal proteins from diverse Bacillus thuringiensis strain collections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.; O’Neil, S.; Ben-Dov, E.; Jones, A.F.; Murphy, L.; Quail, M.A.; Holden, M.T.G.; Harris, D.; Zaritsky, A.; Parkhill, J. Complete sequence and organization of pBtoxis, the toxin-coding plasmid of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5082–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, A.; Fayad, N.; Makart, L.; Bolotin, A.; Sorokin, A.; Kallassy, M.; Mahillon, J. Role of plasmid plasticity and mobile genetic elements in the entomopathogen Bacillus thuringiensis serovar israelensis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 829–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barloy, F.; Lecadet, M.M.; Delécluse, A. Cloning and sequencing of three new putative toxin genes from Clostridium bifermentans CH18. Gene 1998, 211, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Pérez, V.; Delécluse, A. The Cry toxins and the putative hemolysins of Clostridium bifermentans ser. malaysia are not involved in mosquitocidal activity. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2001, 78, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barloy, F.; Delécluse, A.; Nicolas, L.; Lecadet, M.M. Cloning and expression of the first anaerobic toxin gene from Clostridium bifermentans subsp. malaysia, encoding a new mosquitocidal protein with homologies to Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 3099–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalpani, N.; Altier, D.; Barry, J.; Kassa, A.; Nowatzki, T.M.; Sethi, A.; Zhao, J.-Z.; Diehn, S.; Crane, V.; Sandahl, G.; et al. An Alcaligenes strain emulates Bacillus thuringiensis producing a binary protein that kills corn rootworm through a mechanism similar to Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Ortega, C.; Leininger, C.; Barry, J.; Poland, B.; Yalpani, N.; Altier, D.; Nelson, M.E.; Lu, A.L. Coordinated binding of a two-component insecticidal protein from Alcaligenes faecalis to western corn rootworm midgut tissue. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 183, 107597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklavič, Š.; Kogovšek, P.; Hodnik, V.; Korošec, J.; Kladnik, A.; Anderluh, G.; Gutierrez-Aguirre, I.; Maček, P.; Butala, M.; Miklavič, S.; et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa RhlR-controlled aegerolysin RahU is a low-affinity rhamnolipid-binding protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Elliott, M.R.; Leitinger, N.; Jensen, R.V.; Goldberg, J.B.; Amin, A.R. RahU: An inducible and functionally pleiotropic protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa modulates innate immunity and inflammation in host cells. Cell. Immunol. 2011, 270, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rao, J.; DiGiandomenico, A.; Unger, J.; Bao, Y.; Polanowska-Grabowska, R.K.R.K.; Goldberg, J.B.J.B. A novel oxidized low-density lipoprotein-binding protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 2008, 154, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kočar, E.; Lenarčič, T.; Hodnik, V.; Panevska, A.; Huang, Y.; Bajc, G.; Kostanjšek, R.; Naren, A.P.A.P.; Maček, P.; Anderluh, G.; et al. Crystal structure of RahU, an aegerolysin protein from the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and its interaction with membrane ceramide phosphorylethanolamine. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Cheng, X.; Li, L.; Li, J. Identification of Trichoplusia ni ascovirus 2c virion structural proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 2194–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Xian, W.-F.; Xue, J.; Wei, Y.-L.; Cheng, X.-W.; Wang, X. Complete genome sequence of a renamed isolate, Trichoplusia ni Ascovirus 6b, from the United States. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00148-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-H.; Hou, D.-H.; Wang, M.; Cheng, X.-W.; Hu, Z. Genome analysis of Heliothis virescens ascovirus 3h isolated from China. Virol. Sin. 2017, 32, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaghloul, H.A.H.; Hice, R.; Arensburger, P.; Federici, B.A. Early in vivo transcriptome of Trichoplusia ni ascovirus core genes. J. Gen. Virol. 2022, 103, 001737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, J.S.; Regan, L. Aromatic rescue of glycine in β sheets. Fold. Des. 1998, 3, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderluh, G.; Kisovec, M.; Kraševec, N.; Gilbert, R.J.C. Distribution of MACPF/CDC Proteins. Subcell. Biochem. 2014, 80, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 2007, 49, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Dueñas, F.J.; Barrasa, J.M.; Sánchez-García, M.; Camarero, S.; Miyauchi, S.; Serrano, A.; Linde, D.; Babiker, R.; Drula, E.; Ayuso-Fernández, I.; et al. Genomic analysis enlightens Agaricales lifestyle evolution and increasing peroxidase diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Ying, S.-H.; Zheng, P.; Wang, Z.-L.; Zhang, S.; Xie, X.-Q.; Shang, Y.; St. Leger, R.J.; Zhao, G.-P.; Wang, C.; et al. Genomic perspectives on the evolution of fungal entomopathogenicity in Beauveria bassiana. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.X.; Pryor, B.; Peever, T.; Lawrence, C.B. The Alternaria genomes database: A comprehensive resource for a fungal genus comprised of saprophytes, plant pathogens, and allergenic species. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folman, L.B.; Klein Gunnewiek, P.J.A.; Boddy, L.; De Boer, W. Impact of white-rot fungi on numbers and community composition of bacteria colonizing beech wood from forest soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 63, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneitel, J. Gause’s Competitive Exclusion Principle. In Encyclopedia of Ecology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1731–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Klepzig, K.D. Competition between a biological control fungus, Ophiostoma piliferum, and symbionts of the southern pine beetle. Mycologia 1998, 90, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyshen, M.D. Wood decomposition as influenced by invertebrates. Biol. Rev. 2016, 91, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Deen, I.H.S.; Twaij, H.A.A.; Al-Badr, A.A.; Istarabadi, T.A.W. Toxicologic and histopathologic studies of Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1987, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S. Insect pathogenic fungi: Genomics, molecular interactions, and genetic improvements. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yi, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, C. Empirical support for the pattern of competitive exclusion between insect parasitic fungi. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, P.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, C. Genetics of Cordyceps and related fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 2797–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, L.; Chen, M.; Shang, Y.; Tang, G.; Tao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Huang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhan, S.; Wang, C. Population genomics and evolution of a fungal pathogen after releasing exotic strains to control insect pests for 20 years. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsa, S.; Ortiz, V.; Vega, F.E. Establishing fungal entomopathogens as endophytes: Towards endophytic biological control. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 74, e50360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownley, B.H.; Gwinn, K.D.; Vega, F.E. Endophytic fungal entomopathogens with activity against plant pathogens: Ecology and evolution. In The Ecology of Fungal Entomopathogens; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.; Bazopoulou, D.; Pujol, N.; Tavernarakis, N.; Ewbank, J.J. Genome-wide investigation reveals pathogen-specific and shared signatures in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to infection. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Peng, D.; Cheng, C.; Zhou, W.; Ju, S.; Wan, D.; Yu, Z.; Shi, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, F.; et al. Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein Cry6Aa triggers Caenorhabditis elegans necrosis pathway mediated by aspartic protease (ASP-1). PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestsov, G.V.; Lushnikov, O.V.; Glazunova, A.V. Nematopathogenic fungi as the basis of the biological control of root-knot nematodes. Agrar. Sci. 2019, 326, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanes, D.; Richards, T.A. Horizontal gene iransfer in eukaryotic plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 583–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnepf, E.; Crickmore, N.; Van Rie, J.; Lereclus, D.; Baum, J.; Feitelson, J.; Zeigler, D.R.; Dean, D.H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 775–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajid, M.; Geng, C.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, J.; Peng, D.; Sun, M. Whole-genome analysis of Bacillus thuringiensis revealing partial genes as a source of novel Cry toxins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00277-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lieberman, J. Knocking ’em dead: Pore-forming proteins in immune defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 455–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scopus Title-Abstract-Keywords Search. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic#basic (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Grigoriev, I.V.; Nikitin, R.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Ohm, R.; Otillar, R.; Riley, R.; Salamov, A.; Zhao, X.; Korzeniewski, F.; et al. MycoCosm portal: Gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D699–D704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, K.L.; Contreras-Moreira, B.; De Silva, N.; Maslen, G.; Akanni, W.; Allen, J.; Alvarez-Jarreta, J.; Barba, M.; Bolser, D.M.; Cambell, L.; et al. Ensembl Genomes 2020—enabling non-vertebrate genomic research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D689–D695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensembl Fungi Release 54—Jul 2022 © EMBL-EBI. Available online: https://fungi.ensembl.org/index.html (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Kubicek, C.P.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Martinez, D.A.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Thon, M.; Zeilinger, S.; Casas-Flores, S.; Horwitz, B.A.; Mukherjee, P.K.; et al. Comparative genome sequence analysis underscores mycoparasitism as the ancestral life style of Trichoderma. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondego, J.M.C.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Costa, G.G.L.; Formighieri, E.F.; Parizzi, L.P.; Rincones, J.; Cotomacci, C.; Carraro, D.M.; Cunha, A.F.; Carrer, H.; et al. A genome survey of Moniliophthora perniciosa gives new insights into Witches’ Broom Disease of cacao. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, M.B.; Cerqueira, G.C.; Inglis, D.O.; Skrzypek, M.S.; Binkley, J.; Chibucos, M.C.; Crabtree, J.; Howarth, C.; Orvis, J.; Shah, P.; et al. The Aspergillus Genome Database (AspGD): Recent developments in comprehensive multispecies curation, comparative genomics and community resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D653–D659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, N.D.; Khaldi, N.; Joardar, V.S.; Maiti, R.; Amedeo, P.; Anderson, M.J.; Crabtree, J.; Silva, J.C.; Badger, J.H.; Albarraq, A.; et al. Genomic islands in the pathogenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronning, C.M.; Fedorova, N.D.; Bowyer, P.; Coulson, R.; Goldman, G.; Stanley Kim, H.; Turner, G.; Wortman, J.R.; Yu, J.; Anderson, M.J.; et al. Genomics of Aspergillus fumigatus. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2005, 22, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joardar, V.; Abrams, N.F.; Hostetler, J.; Paukstelis, P.J.; Pakala, S.; Pakala, S.B.; Zafar, N.; Abolude, O.O.; Payne, G.; Andrianopoulos, A.; et al. Sequencing of mitochondrial genomes of nine Aspergillus and Penicillium species identifies mobile introns and accessory genes as main sources of genome size variability. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesth, T.C.; Nybo, J.L.; Theobald, S.; Frisvad, J.C.; Larsen, T.O.; Nielsen, K.F.; Hoof, J.B.; Brandl, J.; Salamov, A.; Riley, R.; et al. Investigation of inter- and intraspecies variation through genome sequencing of Aspergillus section Nigri. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.R.; Salazar, M.P.; Schaap, P.J.; Van De Vondervoort, P.J.I.; Culley, D.; Thykaer, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Nielsen, K.F.; Albang, R.; Albermann, K.; et al. Comparative genomics of citric-acid-producing Aspergillus niger ATCC 1015 versus enzyme-producing CBS 513.88. Genome Res. 2011, 21, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Pontes, M.V.; Brandl, J.; McDonnell, E.; Strasser, K.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Riley, R.; Mondo, S.; Salamov, A.; Nybo, J.L.; Vesth, T.C.; et al. The gold-standard genome of Aspergillus niger NRRL 3 enables a detailed view of the diversity of sugar catabolism in fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2018, 91, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, M.; Asai, K.; Sano, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kumagai, T.; Terai, G.; Kusumoto, K.-I.; Arima, T.; Akita, O.; Kashiwagi, Y.; et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae. Nature 2005, 438, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, C.K.; Pham, X.Q.; Erwin, A.L.; Mizoguchi, S.D.; Warrener, P.; Hickey, M.J.; Brinkman, F.S.L.; Hufnagle, W.O.; Kowalik, D.J.; Lagrou, M.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 2000, 406, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClustalW 2.1 (Kyoto University Bioinformatics Centre). Available online: https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Jones, D.T.; Taylor, W.R.; Thornton, J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Bioinformatics 1992, 8, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UCSF ChimeraX. Available online: http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozdetskiy, A.; Cole, C.; Procter, J.; Barton, G.J. JPred4: A protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W389–W394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organism Name | Other Names | Taxonomy | Lifestyle/Niche | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | ||||

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Oyster mushroom Hiratake | Agaricomycotina Agaricales | Saprotroph White rot Nematocidal | [15] |

| Pleurotus eryngii | King oyster or trumpet or brown mushroom Boletus of the steppes French horn mushroom Aliʻi oyster | Agaricomycotina Agaricales | Saprotroph Grassland-litter decomposer Facultatively biotrophic Nematocidal | [16] |

| Cyclocybe aegerita | Agrocybe aegerita Poplar mushroom Tea tree mushroom Cha shu gu Yanagi-matsutake Sword-belt mushroom Velvet pioppini | Agaricomycotina Agaricales | Saprotroph Weak white rot on hardwoods Facultatively pathogenic | [17] |

| Moniliophthora perniciosa | Crinipellis perniciosa Witches’ broom disease | Agaricomycotina Agaricales | Hemibiotrophic plant pathogen Broad range of host | [18] |

| Lignosus rhinocerotis | Tiger milk mushroom | Agaricomycotina Polyporales | Saprotroph White rot | [19] |

| Neosartorya fumigata | Aspergillus fumigatus | Eurotimycetes Eurotiales | Saprotroph Ubiquitous in soil and compost Human (opportunistic) pathogen | [20,21,22,23] |

| Aspergillus niger | Eurotimycetes Eurotiales | Saprotroph Ubiquitous in soil and compost Human opportunistic pathogen | [20,21,24,25,26,27] | |

| Aspergillus terreus | Eurotimycetes Eurotiales | Saprotroph Human opportunistic pathogen | [20,21,28] | |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Eurotimycetes Eurotiales | Saprotroph | [20,21,29] | |

| Beauveria bassiana | Sordariomycetes Hypocreales | Entomopathogen Endophyte Soil and insects | [30,31] | |

| Hypocrea atroviridis | Trichoderma atroviride | Sordariomycetes Hypocreales | Mycoparasitic (including oomycetes) Cosmopolitan, soil | [32,33,34,35] |

| Alternaria geisen | Black spot of Japanese pear | Dothideomycetes Pleosporales | Plant pathogen | [36,37] |

| Bacteria | ||||

| Bacillus thuringiensis | Firmicutes | Ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen on vertebrates, plants, insects, nematodes, mollusks, protozoan, animal, and human parasites. Soils, grain dusts, dead insects, water Aerobic and spore-forming | [38,39] | |

| Paraclostridium bifermentans subsp. malaysia | Clostridium bifermentans subsp. malaysia | Firmicutes | Anaerobic, forming endospores Mosquito larvicidal | [40] |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | Proteobacteria | Soil, water, environments associated with humans Human opportunistic pathogen Nematocidal | [41] | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Proteobacteria | Ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen on: humans, vertebrates, plants, and insects | [42,43,44,45,46] | |

| Insecta | ||||

| Chrysodeixis includens | Pseudoplusia includes | Lepidoptera Noctuidae | Plant pest (defoliator) Larvae feed on a wide range of plants | [47,48] |

| Viria | ||||

| Trichoplusia ni ascovirus 6a1 | Trichoplusia ni ascovirus 2c | Varidnaviria Ascoviridae | Obligate pathogen P. includens moth larvae | [47,49,50,51] |

| Short Name | Aegerolysin/ Structure | Membrane Receptor | Function | Partner Protein Short Name | Partner Protein/ Structure | Organism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PlyA | Pleurotolysin A PDB ID: 4OEBA | SM/Chol | n.d. | PlyB | Pleurotolysin B PDB ID: 4OEJ Membrane embedded PlyA/PlyB pore PDB ID: 4V2T | Pleurotus ostreatus | [59,61] |

| OlyA | Ostreolysin A | SM/Chol CPE/Chol Lipid rafts | Involvement in mushroom fruiting Anticancer (+PlyB) | PlyB | Pleurotolysin B PDB ID: 4OEJ | Pleurotus ostreatus | [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,76,80,84,85,86,102,104] |

| OlyA6 | Ostreolysin A6 PDB ID: 6MYJ | SM/Chol CPE/Chol CAEP/POPC/Chol Lipid rafts | Insecticidal (+PlyB) | PlyB | Pleurotolysin B PDB ID: 4OEJ | Pleurotus ostreatus | [72,73,74,75,78,79,80,81,82,83,87] |

| rOly | Recombinant ostreolysin | Lipid rafts? | Antiproliferative Pro-apoptotic | n.d. | n.d. | Pleurotu ostreatus | [88,89,90] |

| PlyA2 | Pe.PlyA/Pleurotolysin A2 | SM/Chol CPE/Chol CPE Lipid rafts | Insecticidal (+PlyB) | EryB | Erylysin B | Pleurotus eryngii | [15,79,80,93,94,95,96] |

| EryA | Erylysin A | CPE/Chol CL/DPPC/Chol | Insecticidal (+PlyB) Inhibition of cytokinesis | No | No | Pleurotus eryngii | [78,80,96,98,99] |

| Aa-Pri1 | Aegerolysin Aa-Pri1 | n.d. | No | No | Agrocybe aegerita | [63,100] | |

| MpPRIA1 | Putative aegerolysin | n.d. | MpPLYB? | n.d. | Moniliophthora perniciosa | [101] | |

| MpPRIA2 | Putative aegerolysin | n.d. | MpPLYB? | n.d. | Moniliophthora perniciosa | [101] | |

| GME7309 | GME7309_g aegerolysin-domain-containing protein | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Lignosus rhinocerotis | [105] | |

| Asp-HS | Asp-hemolysin | Oxidized low-density lipoproteins | Cytotoxic effects on murine macrophages and vascular endothelial cells Induce cytokine genes | Asp-HSB | n.d. | Aspergillus fumigatus | [107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115] |

| Asp-HS-like | Asp hemolysin-like | n.d. | n.d. | No | No | Aspergillus fumigatus | [114] |

| NigA1 | Nigerolysin A1 | n.d. | n.d. | No | No | Aspergillus niger | [91,92] |

| NigA2 | Nigerolysin A2 | CPE/Chol | n.d. | NigB1 | Nigerolysin B1 | Aspergillus niger | [91,92] |

| Ter | Terrelysin | n.d. | n.d. | No | No | Aspergillus terreus | [28,116,117] |

| AoHlyA | Aspergillus oryzae hemolysin | n.d. | n.d. | No | No | Aspergillus oryzae | [118,119,120] |

| BlyA | Beauveriolysin A | SM/Chol CPE/Chol | n.d. | BlyB | Beauveriolysin B | Beauveria bassiana | [52] |

| Agl1 | Trichoderma atroviride aegerolysin | Conidiation Antagonism | n.d. | No | No | Trichoderma atroviride | [128] |

| L152 | Alternaria geisen aegerolysin | n.d. | n.d. | L152B | n.d. | Alternaria geisen | [36] |

| Cry34Ab1 (Gpp34Ab1) | 13.6 kDa Insecticidal crystal protein PDB ID: 4JOX | Unknown protein receptor | Insecticidal (+Cry34Ab1) | Cry35Ab1 (Tpp35Ab1) | 43.8 kDa insecticidal crystal protein PDB ID: 4JP0 | Bacillus thuringiensis | [39,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136] |

| Cbm17.1 | Hemolysin-like protein Cbm17.1 | n.d. | Insecticidal (+Cry16Aa/Cry17Aa/ Cbm17.2) | Cry16Aa, Cry17Aa, Cbm17.2 | Pesticidal crystal-like protein Cry16Aa and Cry17Aa, Hemolysin-like protein Cbm17.2 | Clostridium bifermentans | [40,140,142] |

| Cbm17.2 | Hemolysin-like protein Cbm17.2 | n.d. | Insecticidal (+Cry16Aa/Cry17Aa/ Cbm17.1) | Cry16Aa, Cry17Aa, Cbm17.2 | Pesticidal crystal-like protein Cry16Aa and Cry17Aa, Hemolysin-like protein Cbm17.1 | Clostridium bifermentans | [40,140,142] |

| AfIP-1A | Two-component insecticidal protein 16 kDa unit PDB ID: 5V3S | Unknown protein receptor AfIP-1A/AfIP-1B membrane pore | n.d. | AfIP-1B | Two-component insecticidal protein 77 kDa unit | Alcaligenes faecalis | [143,144] |

| RahU | RahU protein PDB ID: 6ZC1 | CPE/Chol | n.d. | No | No | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [145,148] |

| P23 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | No | No | Pseudoplusia includes | [48] |

| TnAV2cgp029 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | No | No | Trichoplusia ni ascovirus 2c | [49,50,149,150,152] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kraševec, N.; Skočaj, M. Towards Understanding the Function of Aegerolysins. Toxins 2022, 14, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14090629

Kraševec N, Skočaj M. Towards Understanding the Function of Aegerolysins. Toxins. 2022; 14(9):629. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14090629

Chicago/Turabian StyleKraševec, Nada, and Matej Skočaj. 2022. "Towards Understanding the Function of Aegerolysins" Toxins 14, no. 9: 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14090629

APA StyleKraševec, N., & Skočaj, M. (2022). Towards Understanding the Function of Aegerolysins. Toxins, 14(9), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14090629