Secondary Metabolites of Lasiodiplodia theobromae: Distribution, Chemical Diversity, Bioactivity, and Implications of Their Occurrence

Abstract

1. Introduction

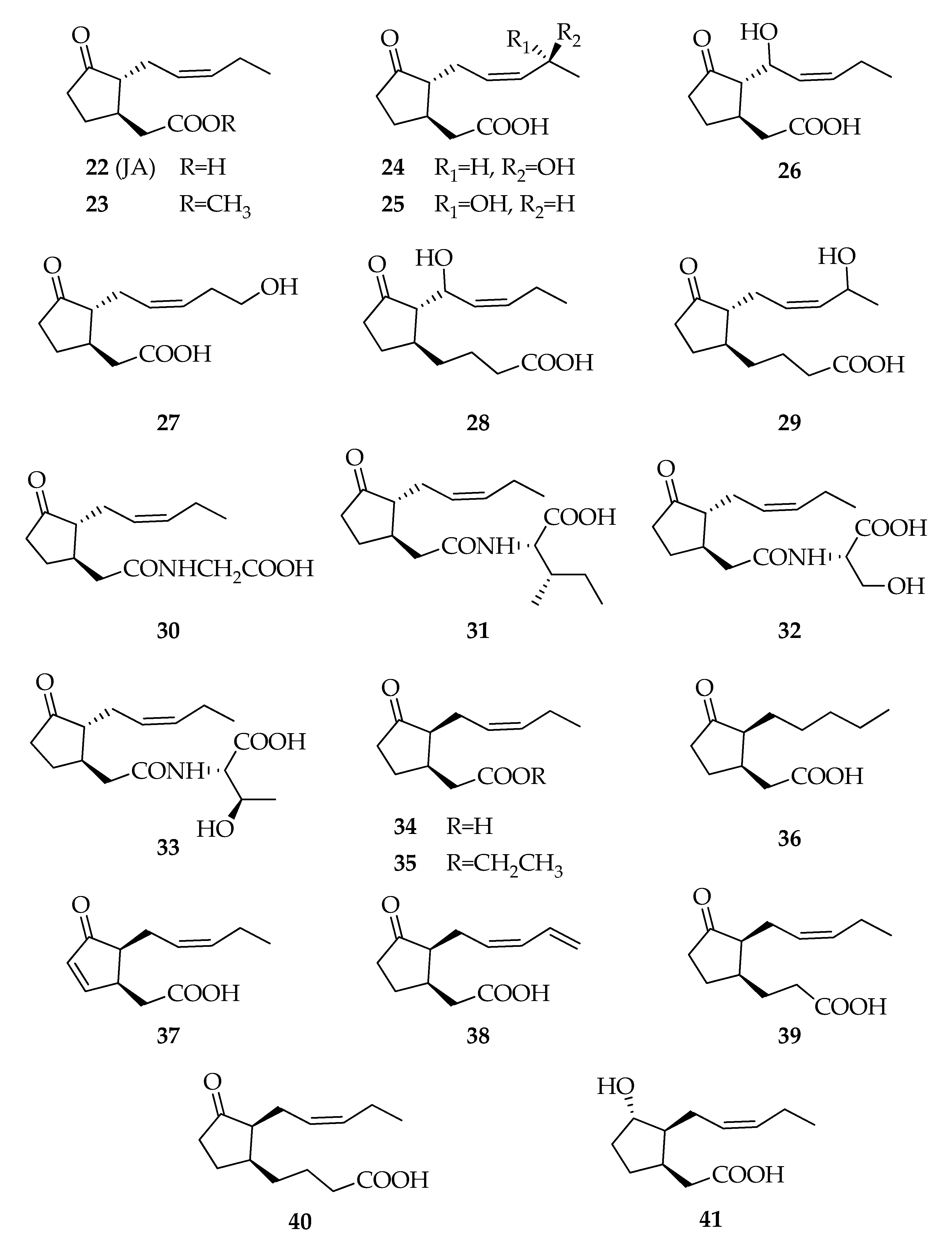

2. Secondary Metabolites

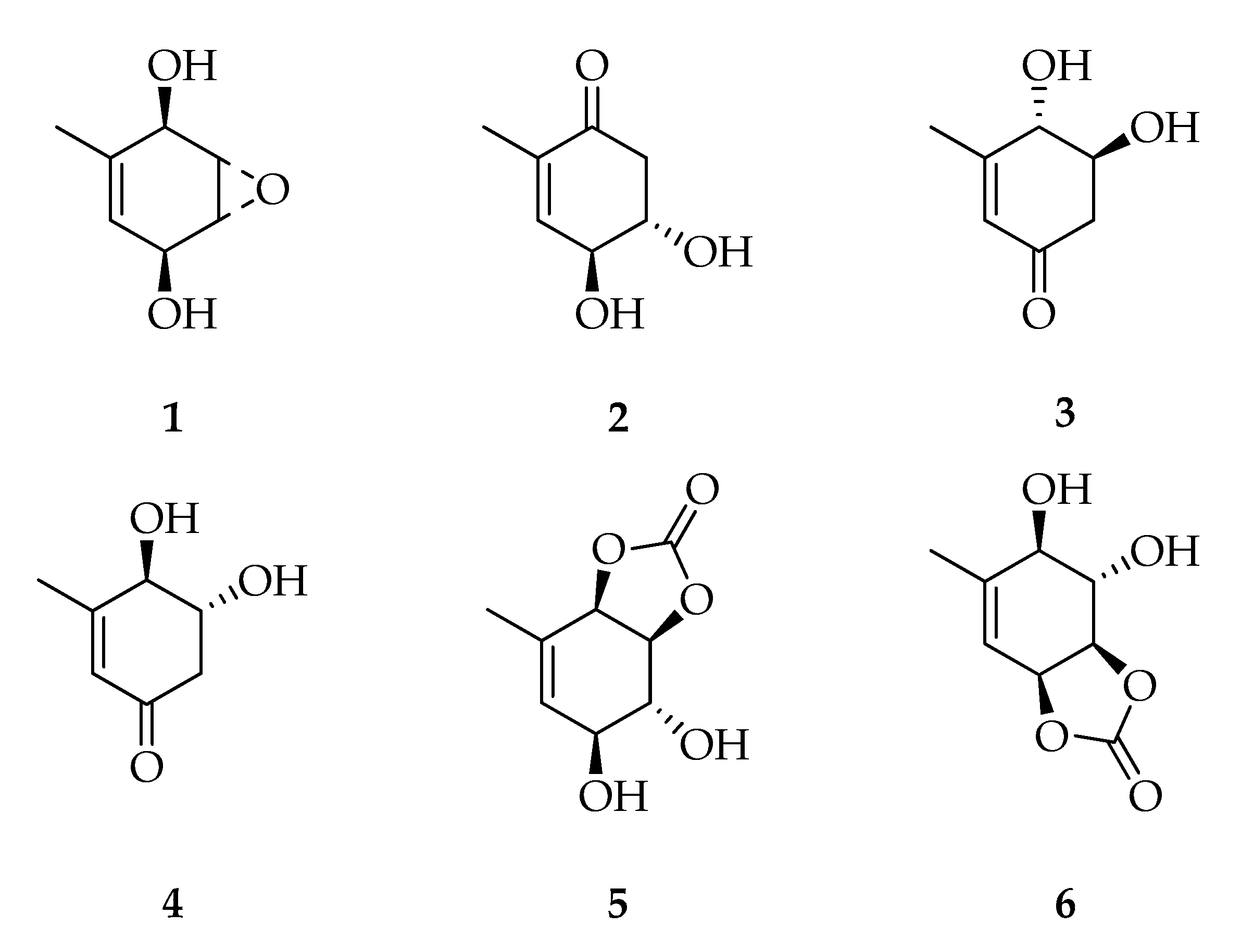

2.1. Cyclohexenes and Cyclohexenones

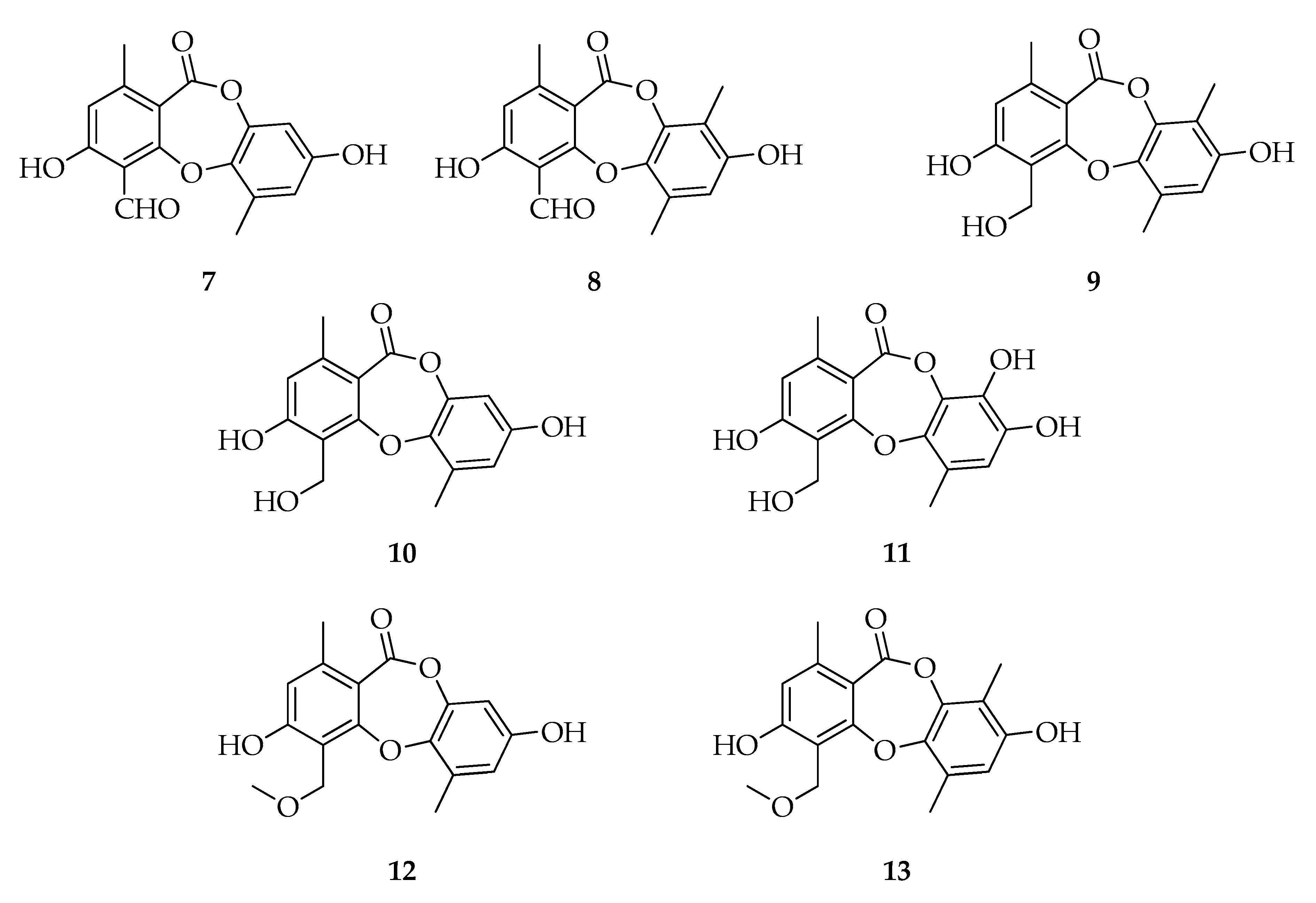

2.2. Depsidones

2.3. Diketopiperazines

2.4. Indoles

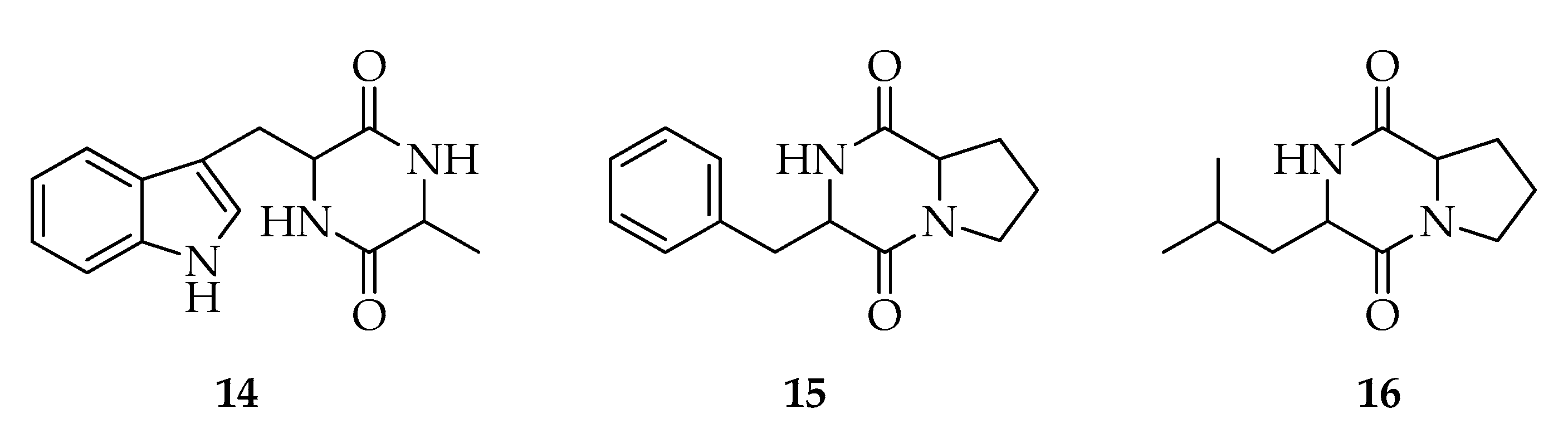

2.5. Jasmonates

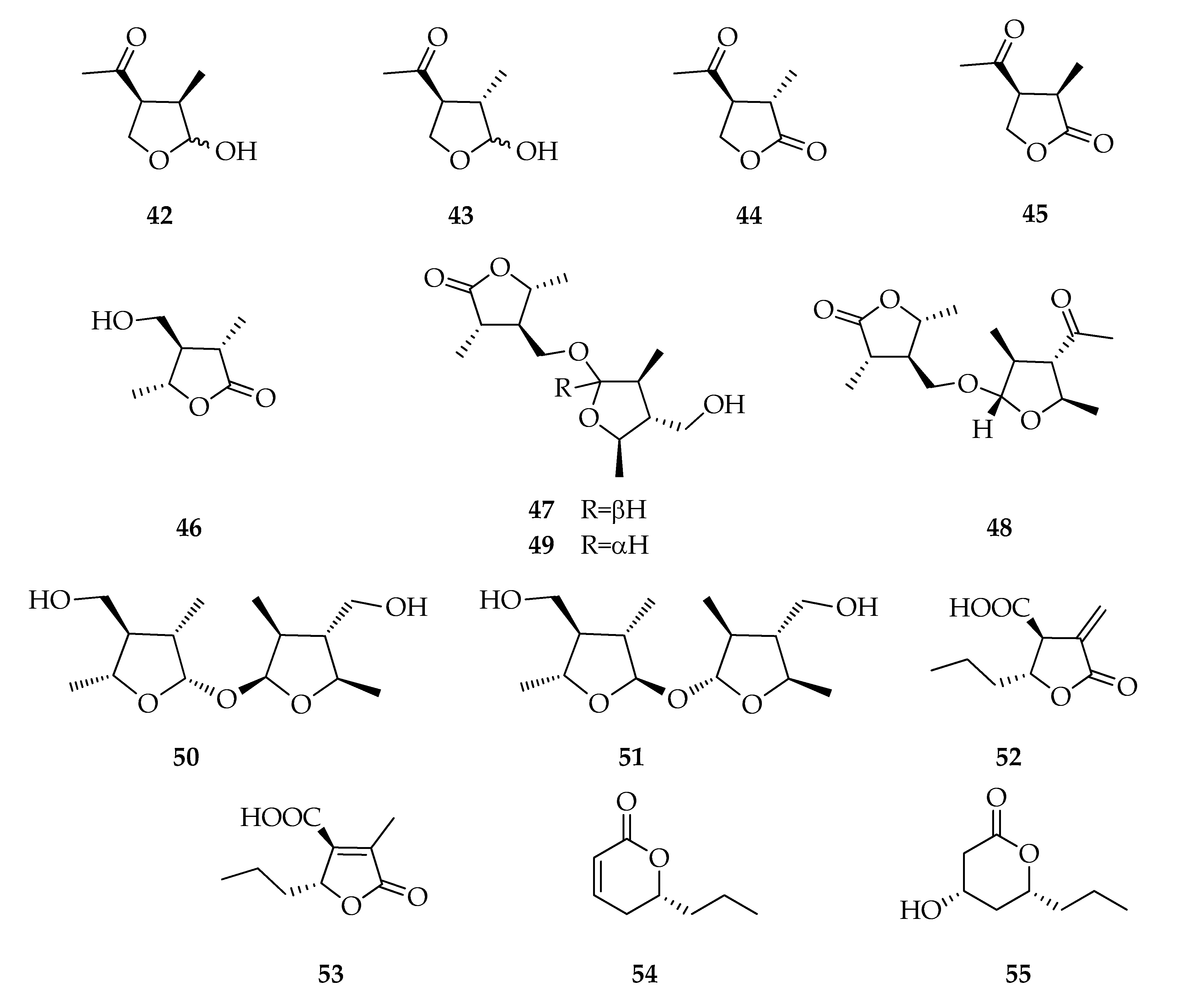

2.6. Lactones and Analogues

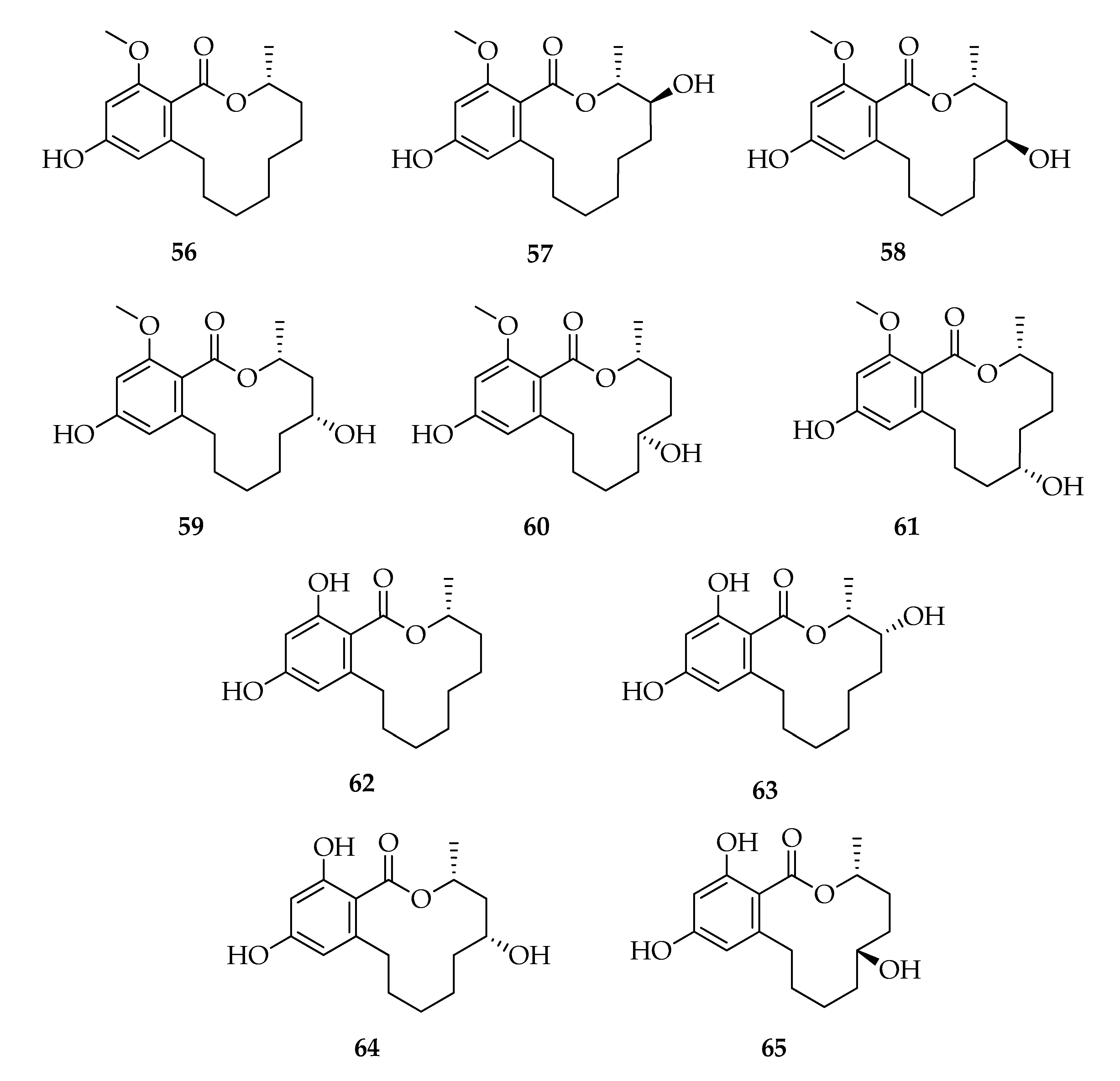

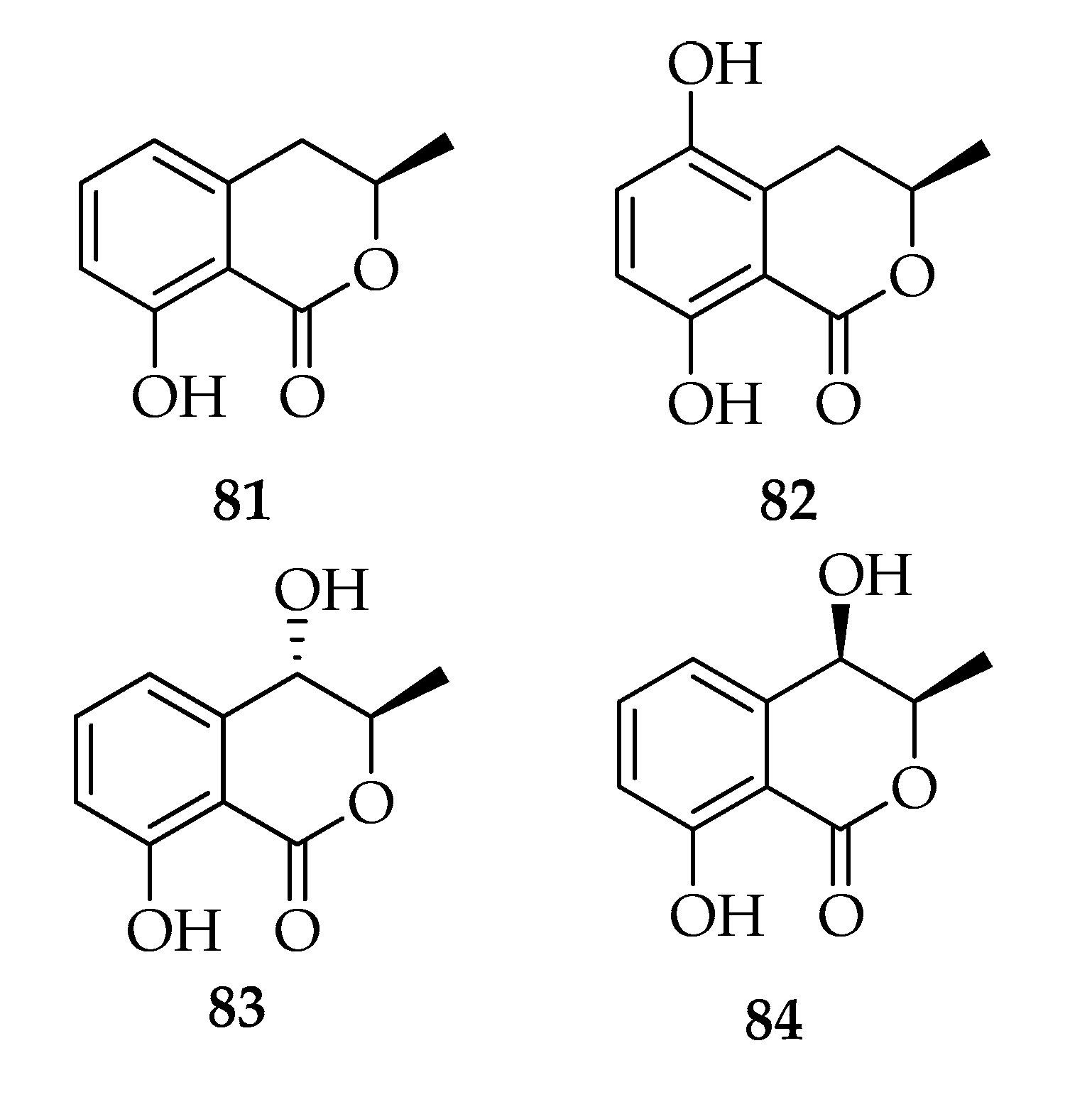

2.7. Lasiodiplodins

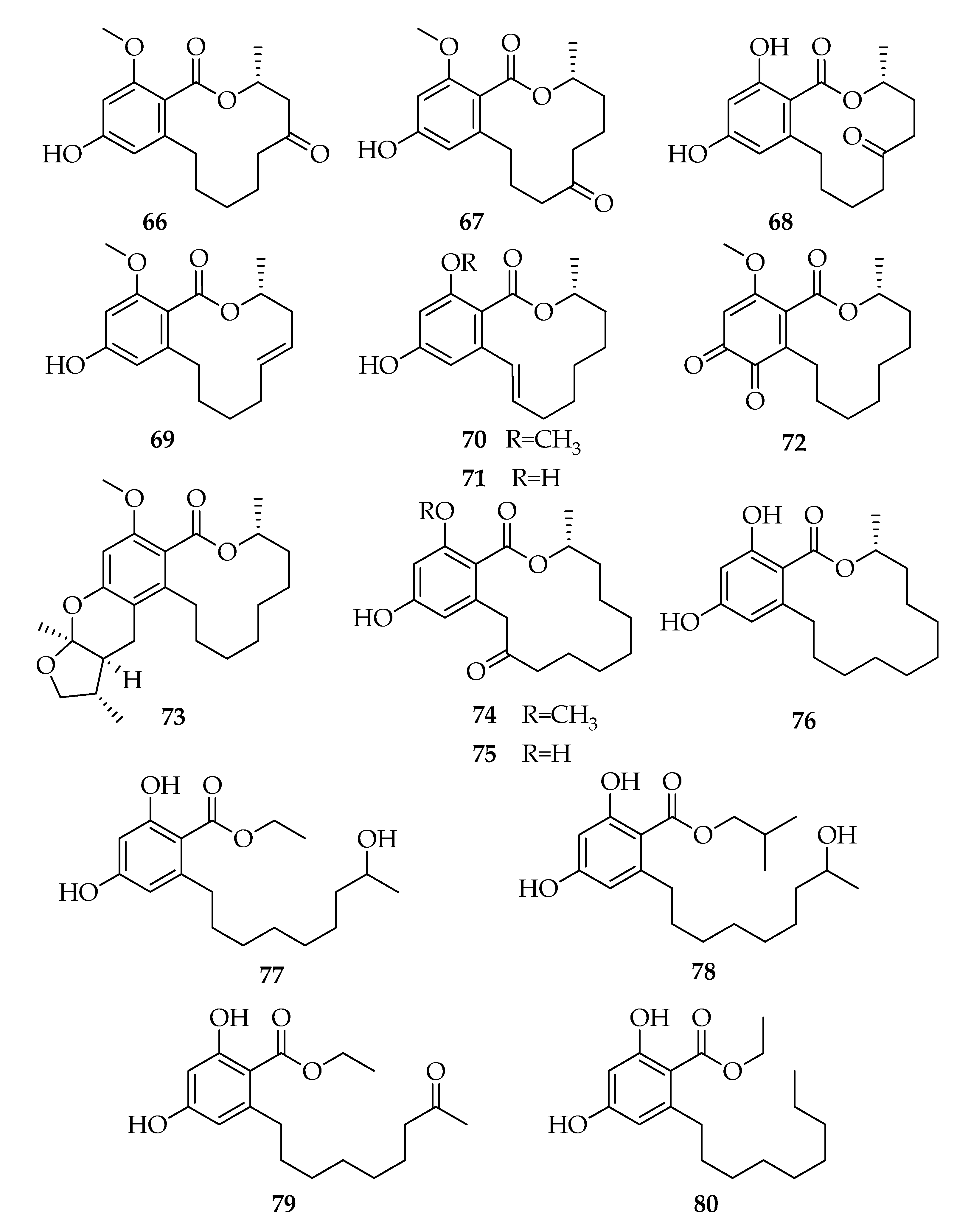

2.8. Melleins

2.9. Phenyl and Phenol Derivates

2.10. 2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones

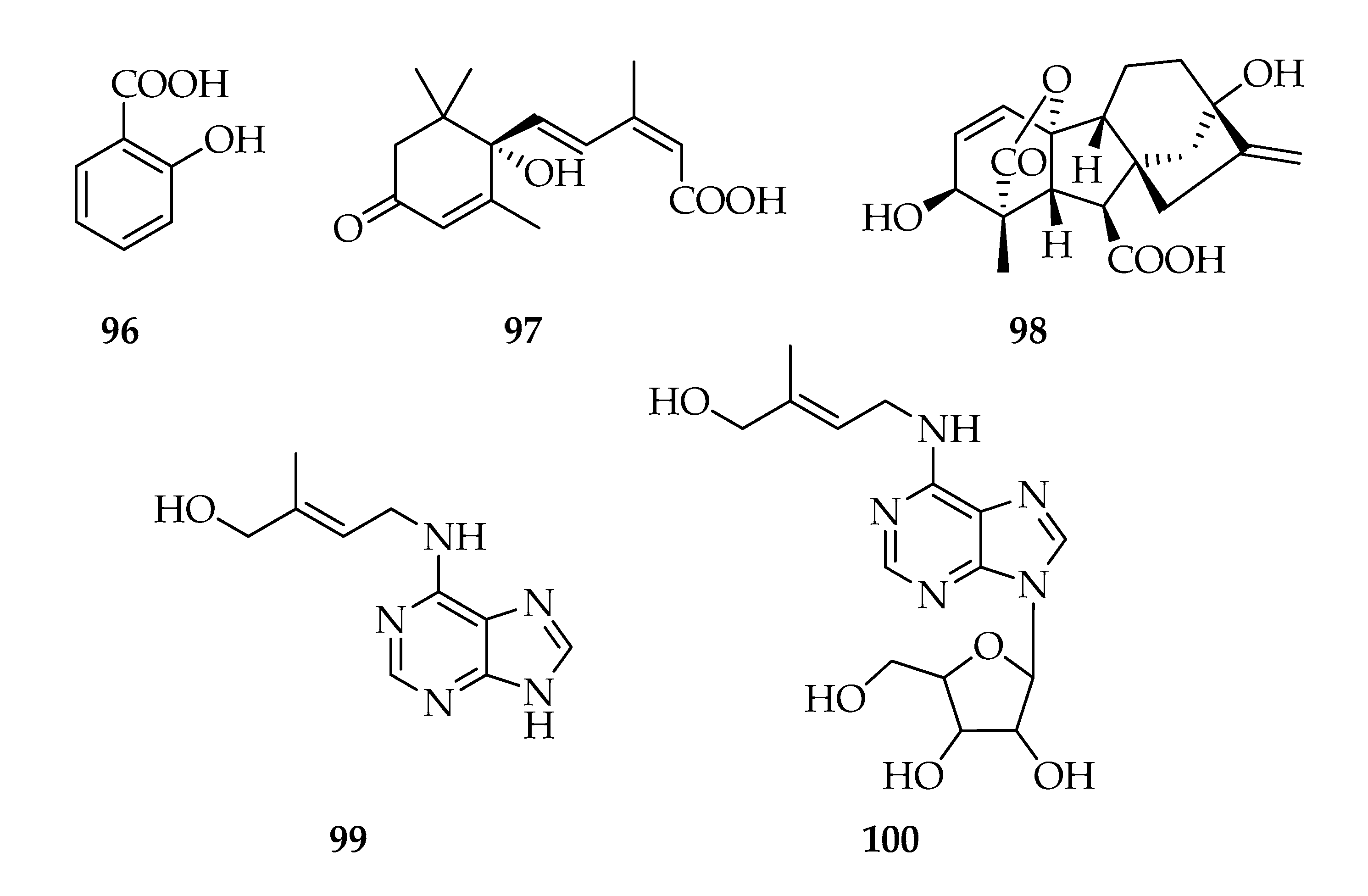

2.11. Phytohormones

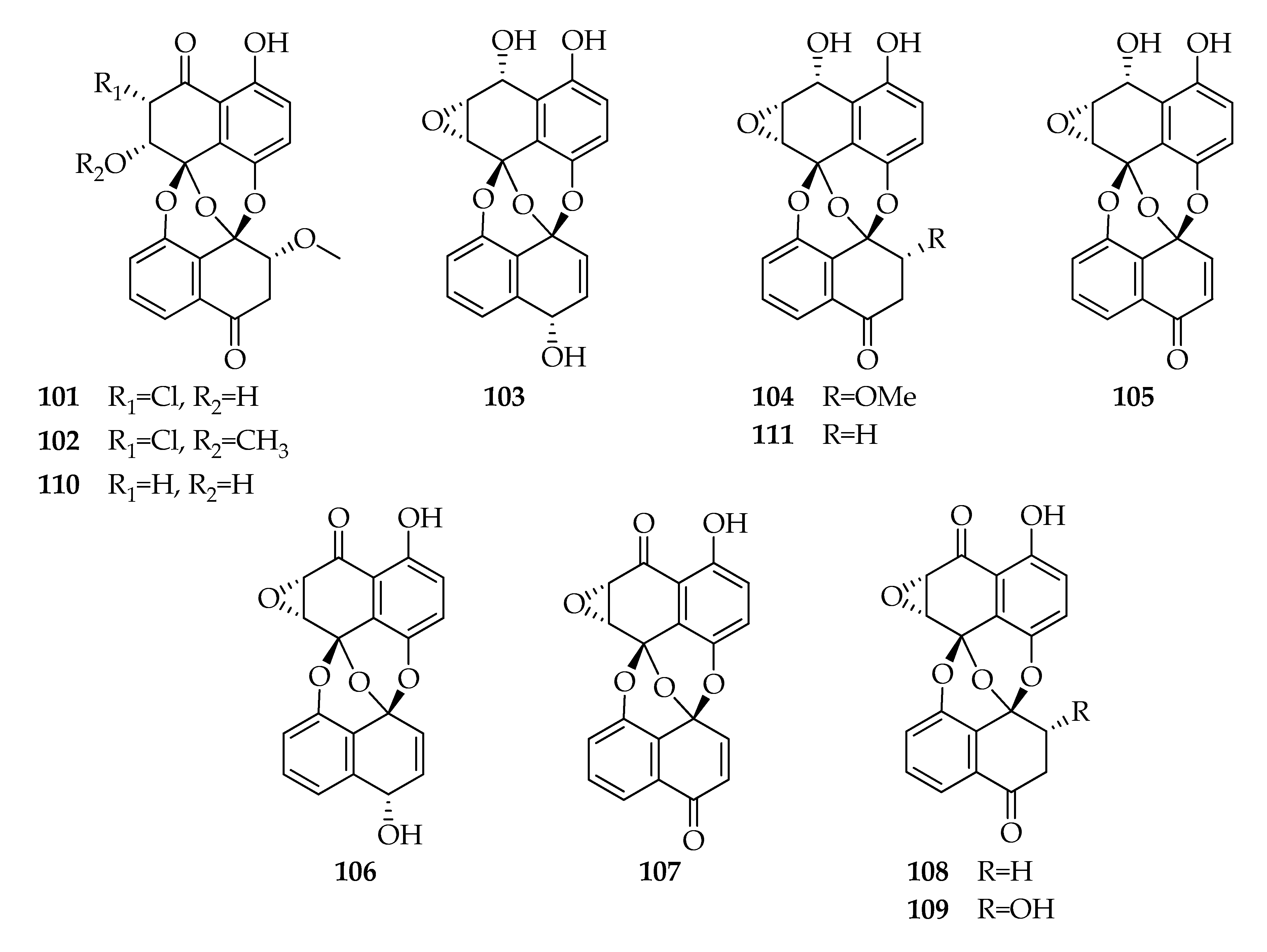

2.12. Preussomerins

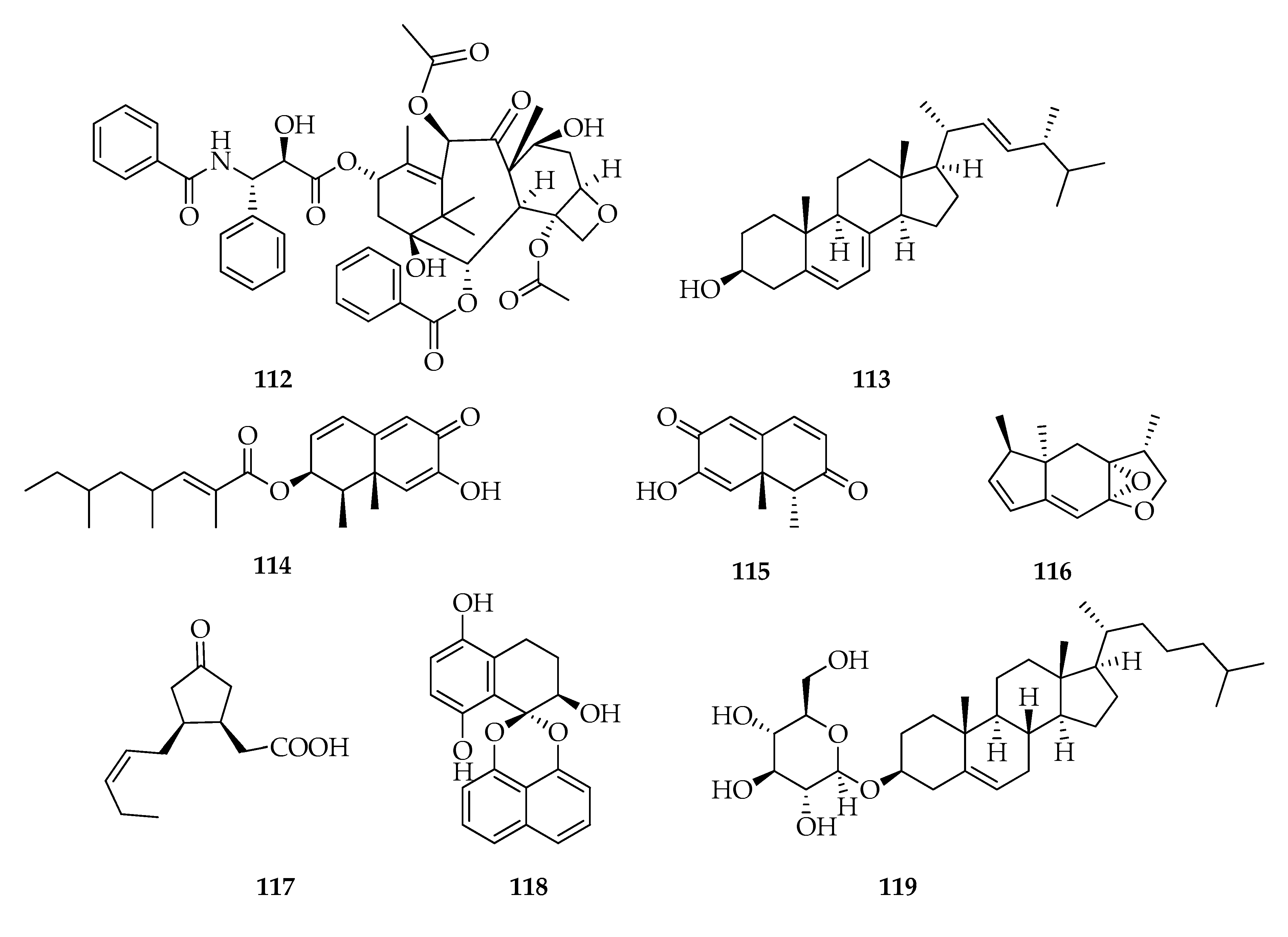

2.13. Miscellaneous

3. Fatty acids

4. Effect of Growth Conditions on Low Molecular Weight Compounds Production

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phillips, A.J.L.; Alves, A.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The Botryosphaeriaceae: Genera and species known from culture. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 76, 51–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, J.; Wingfield, M.J.; Roux, J.; Slippers, B. Invasive everywhere? Phylogeographic analysis of the globally distributed tree pathogen Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Forests 2017, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punithalingam, E. Botryodiplodia theobromae. C.M.I. Descript. Fungi Bact. 1976, 519, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J. Botryosphaeriaceae as endophytes and latent pathogens of woody plants: Diversity, ecology and impact. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, D.F.; Rossman, A.Y. Fungal Databases. Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, ARS, USDA. Available online: http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Summerbell, R.C.; Krajden, S.; Levine, R.; Fuksa, M. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Lasiodiplodia theobromae and successfully treated surgically. Med. Mycol. 2004, 42, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacostas, L.J.; Henderson, A.; Choong, K.; Sowden, D. An unusual skin lesion caused by Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2015, 8, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekhanont, K.; Nonpassopon, M.; Nimvorapun, N.; Santanirand, P. Treatment with intrastromal and intracameral voriconazole in 2 eyes with Lasiodiplodia theobromae keratitis. Medicine 2015, 94, e541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Shalin, S.C.; Kothari, A.; Rico, J.C.C.; Caradine, K.; Burgess, M. Lasiodiplodia species fungal osteomyelitis in a multiple myeloma patient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2016, 18, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Crous, P.W.; Correia, A.; Phillips, A.J.L. Morphological and molecular data reveal cryptic speciation in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Fungal Divers. 2008, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Félix, C.; Libório, S.; Nunes, M.; Félix, R.; Duarte, A.S.; Alves, A.; Esteves, A.C. Lasiodiplodia theobromae as a producer of biotechnologically relevant enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbmann, L.; Stingele, F.; Petruccioli, M. Exopolysaccharide production by filamentous fungi: The example of Botryosphaeria rhodina. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2003, 84, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, C.; Salvatore, M.M.; DellaGreca, M.; Ferreira, V.; Duarte, A.S.; Salvatore, F.; Naviglio, D.; Gallo, M.; Alves, A.; Esteves, A.C.; et al. Secondary metabolites produced by grapevine strains of Lasiodiplodia theobromae grown at two different temperatures. Mycologia 2019, 111, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.D.; Fu, Y.H.; Jiang, F.S.; Xu, Z.H.; Cheng, D.Q.; Ding, B.; Gao, C.X.; Ding, Z.S. Lasiodiplodia sp. ME4-2, an endophytic fungus from the floral parts of Viscum coloratum, produces indole-3-carboxylic acid and other aromatic metabolites. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chen, D.; Cai, R.; Cui, H.; Long, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, C.; She, Z. Cytotoxic and antibacterial preussomerins from the mangrove endophytic fungus Lasiodiplodia theobromae ZJ-HQ1. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2397–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, F.; Haroth, S.; Feussner, K.; Meldau, D.; Rekhter, D.; Ischebeck, T.; Brodhun, F.; Feussner, I. Optimized jasmonic acid production by Lasiodiplodia theobromae reveals formation of valuable plant secondary metabolites. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Long, Y.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y.; She, Z. Lasiodiplactone A, a novel lactone from the mangrove endophytic fungus Lasiodiplodia theobromae ZJ-HQ1. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6338–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Khan, D.; Niaz, S.I.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, L. New lasiodiplodins from mangrove endophytic fungus Lasiodiplodia sp. 318#. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 326–332. [Google Scholar]

- Félix, C.; Salvatore, M.M.; DellaGreca, M.; Meneses, R.; Duarte, A.S.; Salvatore, F.; Naviglio, D.; Gallo, M.; Jorrín-Novo, J.V.; Alves, A.; et al. Production of toxic metabolites by two strains of Lasiodiplodia theobromae, isolated from a coconut tree and a human patient. Mycologia 2018, 110, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztahelyi, T.; Holb, I.J.; Pócsi, I. Secondary metabolites in fungus-plant interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbez-Torres, J.R. The status of Botryosphaeriaceae species infecting grapevines. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2011, 50, S5–S45. [Google Scholar]

- Uranga, C.C.; Beld, J.; Mrse, A.; Córdova-Guerrero, I.; Burkart, M.D.; Hernández-Martínez, R. Fatty acid esters produced by Lasiodiplodia theobromae function as growth regulators in tobacco seedlings. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 472, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Matsuura, H.; Yoshihara, T. Isolation of an α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone derivative, a toxin from the plant pathogen Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2803–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.S.; Chandran, R.R.; Divekar, P.V. Botryodiplodin, a new antibiotic from Botryodiplodia theobromae Pat. I. Production, isolation and biological properties. Indian, J. Exp. Biol. 1966, 4, 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge, D.C.; Galt, S.; Giles, D.; Turner, W.B. Metabolites of Lasiodiplodia theobromae. J. Chem. Soc. Org. 1971, 1971, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miersch, O.; Preiss, A.; Sembdner, G.; Schreiber, K. (+)-7-iso-jasmonic acid and related compounds from Botryodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miersch, O.; Schmidt, J.; Sembdner, G.; Schreiber, K. Jasmonic acid-like substances from the culture filtrate of Botryodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1303–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miersch, O.; Schneider, G.; Sembdner, G. Hydroxylated jasmonic acid and related compounds from Botryodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 4049–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Ahmad, A.; Agrawal, P.K. (-)-Jasmonic acid, a phytotoxic substance from Botryodiplodia theobromae: Characterization by NMR spectroscopic methods. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 2008–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamori, K.; Matsuura, H.; Yoshihara, T.; Ichihara, A.; Koda, Y. Potato micro-tuber inducing substances from Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Nago, H. (R)-2-Octeno-δ-lactone and other volatiles produced by Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1994, 58, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, H.; Nakamori, K.; Omer, E.A.; Hatakeyama, C.; Yoshihara, T.; Ichihara, A. Three lasiodiplodins from Lasiodiplodia theobromae IFO 31059. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Asai, M.; Matsuura, H.; Yoshihara, T. Potato micro-tuber inducing hydroxylasiodiplodins from Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Asai, M.; Yoshihara, T. Novel resorcinol derivatives from Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Z. Naturforsch. C. J. Biosci. 2000, 55, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Takahashi, K.; Matsuura, H.; Yoshihara, T. Novel potato micro-tuber-inducing compound, (3R,6S)-6-hydroxylasiodiplodin, from a strain of Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 1610–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Peng, G.T.; She, Z.G.; Zhou, S.N. Lactones from a brown alga endophytic fungus (No. ZZF36) from the South China Sea and their antimicrobial activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4205–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, F.M.; Oliveira, M.C.F.; Arriaga, Â.; Lemos, T.L.; Andrade-Neto, M.; Mattos, M.C.D.; Mafezoli, J.; Viana, F.M.P.; Ferreira, V.M.; Rodrigues-Filho, E.; et al. A new eremophilane-type sesquiterpene from the phytopatogen fungus Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Sphaeropsidaceae). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2008, 19, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, R.; Takahashi, K.; Matsuura, H.; Nabeta, K. New potato micro-tuber-inducing cyclohexene compounds related to theobroxide from Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatachalam, R.; Subban, K.; Paul, M.J. Taxol from Botryodiplodia theobromae (BT 115)-an endophytic fungus of Taxus baccata. J. Biotechnol. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaoka, N.; Nabeta, K.; Matsuura, H. Isolation and structural elucidation of a new cyclohexenone compound from Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 1890–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rukachaisirikul, V.; Arunpanichlert, J.; Sukpondma, Y.; Phongpaichit, S.; Sakayaroj, J. Metabolites from the endophytic fungi Botryosphaeria rhodina PSU-M35 and PSU-M114. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 10590–10595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, R.; Scherlach, K.; Dahse, H.-M.; Sattler, I.; Hertweck, C. Botryorhodines A–D, antifungal and cytotoxic depsidones from Botryosphaeria rhodina, an endophyte of the medicinal plant Bidens pilosa. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi, M.; Kumaran, R.S.; Choi, Y.K.; Kim, H.J.; Muthumary, J. Isolation and detection of taxol, an anticancer drug produced from Lasiodiplodia theobromae, an endophytic fungus of the medicinal plant Morinda citrifolia. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, G.; Torrecillas, A.; Nogueiras, C.; Michelena, G.; Sánchez-Bravo, J.; Acosta, M. Simultaneous quantification of phytohormones in fermentation extracts of Botryodiplodia theobromae by liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, S.; Sun, L.; Blunt, J.W.; Cole, A.L.; Munro, M.H.; Ramasamy, K.; Weber, J.F.F. Evolving trends in the dereplication of natural product extracts. 3: Further lasiodiplodins from Lasiodiplodia theobromae, an endophyte from Mapania kurzii. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valayil, M.J.; Kuriakose, G.C.; Jayabaskaran, C. Isolation, purification and characterization of a novel steroidal saponin cholestanol glucoside from Lasiodiplodia theobromae that induces apoptosis in A549 cells. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xue, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, L. Lasiodiplodins from mangrove endophytic fungus Lasiodiplodia sp. 318#. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 755–760. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hawary, S.S.; Sayed, A.M.; Rateb, M.E.; Bakeer, W.; AbouZid, S.F.; Mohammed, R. Secondary metabolites from fungal endophytes of Solanum nigrum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2568–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.; Viegelmann, C.V.; Clements, C.J.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Metabolomics-guided isolation of anti-trypanosomal metabolites from the endophytic fungus Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Planta Med. 2017, 234, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.X.; Li, W.S.; Tao, M.H.; Pan, Q.L.; Sun, Z.H.; Ye, W.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, W.M. 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromones from endophytic fungal strain Botryosphaeria rhodina A13 from Aquilaria sinensis. Chin. Herb. Med. 2017, 9, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeokoli, B.O.; Ebrahim, W.; El-Neketi, M.; Müller, W.E.; Kalscheuer, R.; Lin, W.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. A new depsidone derivative from mangrove sediment derived fungus Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, Q.; Matsuura, H.; Yoshihara, T. Theobroxide triggers jasmonic acid production to induce potato tuberization in vitro. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 47, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, Q.; Minami, C.; Matsuura, H.; Kimura, A.; Yoshihara, T. Inhibitory effect of salicylhydroxamic acid on theobroxide-induced potato tuber formation. Plant Sci. 2003, 165, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.Y.; Baek, K.H.; Moon, Y.S.; Yun, H.K. Theobroxide treatment inhibits wild fire disease occurrence in Nicotiana benthamiana by the overexpression of defense-related genes. Plant Pathol. J. 2013, 29, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, T.; Ohmori, F.; Nakamori, K.; Amanuma, M.; Tsutsumi, T.; Ichihara, A.; Matsuura, H. Induction of plant tubers and flower buds under noninducing photoperiod conditions by a natural product, theobroxide. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2000, 19, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.R.; Mohamed, G.A.; Al Haidari, R.A.; El-Kholy, A.A.; Zayed, M.F.; Khayat, M.T. Biologically active fungal depsidones: Chemistry, biosynthesis, structural characterization, and bioactivities. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 317–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, R.; Salvatore, M.M.; Andolfi, A. Secondary metabolites of mangrove-associated strains of Talaromyces. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, X.; Xu, T.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Diketopiperazines from marine organisms. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 2809–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, A.D. 2, 5-Diketopiperazines: Synthesis, reactions, medicinal chemistry, and bioactive natural products. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3641–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Jiang, N.; Mei, Y.N.; Chu, Y.L.; Ge, H.M.; Song, Y.C.; Ng, S.W.; Tan, R.X. An antibacterial metabolite from Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae F2. Phytochemistry 2014, 100, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, H. Current aspects of auxin biosynthesis in plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Koga, J.; Adachi, T.; Kishi, K.; Syono, K. Efficient conversion of L-tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid and/or tryptophol by some species of Rhizoctonia. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996, 37, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.J.; Gustafson, M.E.; Rosazza, J.P. Formation of indole-3-carboxylic acid by Chromobacterium violaceum. J. Bacteriol. 1976, 126, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnus, V.; Šimaga, Š.; Iskrić, S.; Kveder, S. Metabolism of tryptophan, indole-3-acetic acid, and related compounds in parasitic plants from the genus Orobanche. Plant Physiol. 1982, 69, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, E.; Bellwon, P.; Huber, S.; Schlaeppi, K.; Bernsdorff, F.; Vallat-Michel, A.; Mauch, F.; Zeier, J. Regulatory and functional aspects of indolic metabolism in plant systemic acquired resistance. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, B. Auxin biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 1997, 48, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Jones, J.D. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1773. [Google Scholar]

- May, M.J.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Jones, J.D.G. Involvement of reactive oxygen species, glutathione metabolism, and lipid peroxidation in the gene-dependent defense response of tomato cotyledons induced by race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum. Plant Physiol. 1996, 110, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B.; Eggermont, K.; Penninckx, I.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Vogelsang, R.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Broekaert, W.F. Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15107–15111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Hause, B. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 1021–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Feussner, I. The oxylipin pathways: Biochemistry and function. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernerén, F.; Eng, F.; Hamberg, M.; Oliw, E.H. Linolenate 9R-dioxygenase and allene oxide synthase activities of Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Lipids 2012, 47, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andolfi, A.; Maddau, L.; Cimmino, A.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Basso, S.; Deidda, A.; Serra, S.; Evidente, A. Lasiojasmonates A–C, three jasmonic acid esters produced by Lasiodiplodia sp., a grapevine pathogen. Phytochemistry 2014, 103, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linaldeddu, B.T.; Deidda, A.; Scanu, B.; Franceschini, A.; Serra, S.; Berraf-Tebbal, A.; Zouaoui Boutiti, M.; Ben Jamâa, M.L.; Phillips, A.J.L. Diversity of Botryosphaeriaceae species associated with grapevine and other woody hosts in Italy, Algeria and Tunisia, with descriptions of Lasiodiplodia exigua and Lasiodiplodia mediterranea sp. nov. Fungal Divers. 2015, 71, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, G.P.; Althaus, J.R.; Divekar, P.V. Structure of the antibiotic botryodiplodin—use of chemical ionization mass spectrometry in organic structure determination. J. Chem. Soc. D Chem. Commun. 1969, 23, 1414–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurry, P.M.; Abe, K. Stereochemistry and synthesis of the antileukemic agent botryodiplodin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 5824–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Amemiya, S.; Inoue, K.; Kojima, K. The conversion of methylenomycin A to natural botryodiplodin and their absolute configurations. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 25, 2365–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S.; Lablache-Combier, A.; Biguet, J.; Foulon, C.; Delfosse, M.J. Botryodiplodin, a mycotoxin synthesized by a strain of P. roqueforti. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 2358–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouguier, R.; Gastaldi, S.; Stien, D.; Bertrand, M.; Villar, F.; Andrey, O.; Renaud, P. Synthesis of (±)- and (−)-botryodiplodin using stereoselective radical cyclizations of acyclic esters and acetals. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2003, 14, 3005–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Félix, C.; Lima, F.; Ferreira, V.; Naviglio, D.; Salvatore, F.; Duarte, A.S.; Alves, A.; Andolfi, A.; Esteves, A.C. Secondary metabolites produced by Macrophomina phaseolina isolated from Eucalyptus globulus. Agriculture 2020, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolfi, A.; Basso, S.; Giambra, S.; Conigliaro, G.; Lo Piccolo, S.; Alves, A.; Burruano, S. Lasiolactols A and B produced by the grapevine fungal pathogen Lasiodiplodia mediterranea. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, W.T.; Abbas, H.K.; Baird, R.E.; Ramezani, M.; Sciumbato, G.L. (-)-Botryodiplodin, a unique ribose-analog toxin. Toxin Rev. 2007, 26, 343–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Mao, H.; Huang, Q.; Dong, J. Benzenediol lactones: A class of fungal metabolites with diverse structural features and biological activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 747–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.H.; Jiang, N.; Dong, C.H.; Wei, Z.W.; Wu, H.K.; Chen, C.F.; Zhao, Y.X.; Zhou, S.L.; Zhang, M.M.; Zheng, W.F. Lasiodiplodin analogues from the endophytic fungus Sarocladium kiliense. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buayairaksa, M.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K.; Moosophon, P.; Hahnvajanawong, C.; Soytong, K. Cytotoxic lasiodiplodin derivatives from the fungus Syncephalastrum racemosum. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011, 34, 2037–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patocka, J.; Soukup, O.; Kuca, K. Resorcylic acid lactones as the protein kinase inhibitors, naturally occuring toxins. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1873–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.S.; Ebizuka, Y.; Noguchi, H.; Kiuchi, F.; Shibuya, M.; Iitaka, Y.; Seto, H.; Sankawa, U. Biologically active constituents of Arnebia euchroma: Structure of arnebinol, an ansa-type monoterpenylbenzenoid with inhibitory activity on prostaglandin biosynthesis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991, 39, 2956–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Andersen, B.; Thrane, U. The use of secondary metabolite profiling in chemotaxonomy of filamentous fungi. Mycol. Res. 2008, 112, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, T.; Takahashi, K.; Matsuura, H.; Nabeta, K. Biosynthesis of resorcylic acid lactone (5S)-5-hydroxylasiodiplodin in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 2522–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saeed, A. Isocoumarins, miraculous natural products blessed with diverse pharmacological activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 116, 290–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, D.; Xu, P. Recent advances in biotechnological production of 2-phenylethanol. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Avila, O.; Sánchez, A.; Font, X.; Barrena, R. Bioprocesses for 2-phenylethanol and 2-phenylethyl acetate production: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 9991–10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucci, P.; Bertoz, V.; Pacetti, D.; Moret, S.; Conte, L. Effect of the refining process on total hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, and tocopherol contents of olive oil. Foods 2020, 9, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, P.; Casadevall, A. Quorum sensing in fungi–a review. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmood, A.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Meng, G.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Fungal quorum-sensing molecules and inhibitors with potential antifungal activity: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, D.K.; Petersen, L.M.; Klitgaard, A.; Knudsen, P.B.; Jarczynska, Z.D.; Nielsen, K.F.; Gotfredsen, C.H.; Larsen, T.O.; Mortensen, U.H. Molecular and chemical characterization of the biosynthesis of the 6-MSA-derived meroterpenoid yanuthone D in Aspergillus niger. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.R.; Mohamed, G.A. Natural occurring 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromones, structure elucidation and biological activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1489–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Isa, N.M.; Zainal, Z. Agarwood induction: Current developments and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, R.; Fiorentino, A. Plant bioactive metabolites and drugs produced by endophytic fungi of Spermatophyta. Agriculture 2015, 5, 918–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.N.; Knowles, S.; Hayward, A.; Thorn, R.G.; Saville, B.J.; Emery, R.J.N. Detection of phytohormones in temperate forest fungi predicts consistent abscisic acid production and a common pathway for cytokinin biosynthesis. Mycologia 2015, 107, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zou, W.X.; Meng, J.C.; Hu, J.; Tan, R.X. New bioactive metabolites produced by Colletotrichum sp., an endophytic fungus in Artemisia annua. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagobaty, R.K.; Joshi, S.R. Promotion of seed germination of green gram and chick pea by Penicillium verruculosum RS7PF, a root endophytic fungus of Potentilla fulgens L. Adv. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta, T.; Hayashi, T. Biochemical studies on Bakanae fungus of rice. Part 3. Physiological action of gibberellin on plants. J. Agric. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1939, 15, 403–413. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.Q.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance: Turning local infection into global defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Radhakrishnan, D.; Prasad, K.; Chini, A. Fungal production and manipulation of plant hormones. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, B.; Topçuoğlu, S.F. GA3, ABA and cytokinin production by Lentinus tigrinus and Laetiporus sulphureus fungi cultured in the medium of olive oil mill waste. Turk. J. Biol. 2001, 25, 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagobaty, R.K.; Joshi, S.R. Metabolite profiling of endophytic fungal isolates of five ethno-pharmacologically important plants of Meghalaya, India. J. Metabolomics Syst. Biol. 2011, 2, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, H.A.; Baenziger, N.C.; Gloer, J.B. Structure of preussomerin A: An unusual new antifungal metabolite from the coprophilous fungus Preussia isomera. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 6718–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, E.; Stockley, M.; Taylor, R.J. The first total syntheses of (±)-Preussomerins K and L using 2-arylacetal anion technology. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 4877–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, A.; Kar, S.; Vignesh, K.; Kolhe, U.D. An overview of paclitaxel delivery systems. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 43; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-41837-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, M.C.; Taylor, H.L.; Wall, M.E.; Caggon, P.; McPhail, A.T. Plant antitumor agents: VI The isolation and structure of taxol, a novel anti leukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, B.S. Developments in taxol production through endophytic fungal biotechnology: A review. Orient. Pharm. Exp. Med. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, H.B.; Walker, M.; Zeeck, A. Cladospirones B to I from Sphaeropsidales sp. F-24′ 707 by variation of culture conditions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 2000, 3185–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinu, M.V.; Gini, C.K.; Jayabaskaran, C. In vitro antioxidant activity of cholestanol glucoside from an endophytic fungus Lasiodiplodia theobromae isolated from Saraca asoca. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 952–962. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, Y.; Subban, K.; Chelliah, J. Enhanced cytotoxicity and apoptotic activity by the combined application of cholestanol glucoside, a novel fungal secondary metabolite and paclitaxel on human cervical cancer cells. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Drug Discovery (ICDD), Hyderabad, India, 29 February–2 March 2020; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3530004 (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Vestal, J.R.; White, D.C. Lipid analysis in microbial ecology. Bioscience 1989, 39, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Nicoletti, R.; Salvatore, F.; Naviglio, D.; Andolfi, A. GC-MS approaches for the screening of metabolites produced by marine-derived Aspergillus. Mar. Chem. 2018, 206, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Vogel, R.L.; Witherup, K.M.; Rutledge, S.J.; Pitzenberger, S.M.; Adam, M.; Rodan, G.A. Identification of fatty acid methyl ester as naturally occurring transcriptional regulators of the members of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor family. Lipids 1996, 31, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.B.; Alimova, Y.; Myers, T.M.; Ebersole, J.L. Short-and medium-chain fatty acids exhibit antimicrobial activity for oral microorganisms. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.H.; Kock, J.L.; Thibane, V.S. Antifungal free fatty acids: A review. Sci. Microb. Pathog. Commun. Curr. Res. Technol. Adv. 2011, 1, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, A.; Stintzi, A. Enzymes in jasmonate biosynthesis-structure, function, regulation. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillardin, C. Lipases as pathogenicity factors of fungi. In Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-540-77584-3. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Giambra, S.; Naviglio, D.; DellaGreca, M.; Salvatore, F.; Burruano, S.; Andolfi, A. Fatty Acids Produced by Neofusicoccum vitifusiforme and N. parvum, fungi associated with grapevine Botryosphaeria dieback. Agriculture 2018, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Schweikert, M.A. Handbook of Secondary Fungal Metabolites; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 9780121794606. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, N.P.; Turner, G.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal secondary metabolism-from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Nicoletti, R.; DellaGreca, M.; Andolfi, A. Occurrence and properties of thiosilvatins. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapuścińska, A.; Nowak, I. Jasmonates as new active substances in pharmaceutical and cosmetic industry. In Proceedings of the 5th European Young Engineers Conference (EYEC), Warsaw, Poland, 20–22 April 2016; Available online: https://eyec.ichip.pw.edu.pl (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Eng, F.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, M.; Favela-Torres, E. Culture conditions for jasmonic acid and biomass production by Botryodiplodia theobromae in submerged fermentation. Proc. Biochem. 1998, 33, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanhukia, P.C.; Thakkaar, V.S. Response surface methodology to optimize the nutritional parameters for enhanced production of jasmonic acid by Lasiodiplodia theobromae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 105, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanhukia, P.C.; Thakkaar, V.S. Significant medium components for enhanced jasmonic acid production by Lasiodiplodia theobromae using Plackett-Burman design. Curr. Trends Biotechol. Pharm. 2007, 1, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanhukia, P.C.; Thakkaar, V.S. Standardization of growth and fermentation criteria of Lasiodiplodia theobromae for production of jasmonic acid. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 707–712. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K.M.; Ponnusamy, M.; Uthandi, S. Evaluation of jasmonic acid production by Lasiodiplodia theobromae under Submerged fermentation. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Valayil, J.M.; Jayabaskaran, C. Media optimization for the production of a bioactive steroidal saponin, cholestanol glucoside by Lasiodiplodia theobromae. European J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Valayil, J.M.; Guriakose, G.C.; Jayabaskaran, C. Modulating the biosynthesis of a bioactive steroidal saponin, cholestanol glucoside by Lasiodiplodia theobromae using abiotic stress factors. Int. J. Pharmacy Pharma. Sci. 2015, 7, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Name | Formula | Nominal Mass (U) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexenes and Cyclohexenones | |||

| 1 | Theobroxide | C7H10O3 | 142 |

| 2 | (4S,5S)-4,5-Dihydroxy-2-methylcyclohex-2-enone | C7H10O3 | 142 |

| 3 | (4S,5S)-4,5-Dihydroxy-3-methylcyclohex-2-enone | C7H10O3 | 142 |

| 4 | (4R,5R)-4,5-Dihydroxy-3-methylcyclohex-2-enone | C7H10O3 | 142 |

| 5 | (3aS,4R,5S,7aR)-4,5-Dihydroxy-7-methyl-3a,4,5,7a-tetrahydrobenzo[1,3]dioxol-2-one | C8H10O5 | 186 |

| 6 | (3aR,4S,5R,7aS)-4,5-Dihydroxy-6-methyl-3a,4,5,7a-tetrahydrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-2-one | C8H10O5 | 186 |

| Depsidones | |||

| 7 | Botryorhodine A | C16H12O6 | 300 |

| 8 | Botryorhodine B | C17H14O6 | 314 |

| 9 | Botryorhodine C | C17H16O6 | 316 |

| 10 | Botryorhodine D | C16H14O6 | 302 |

| 11 | Botryorhodine I | C16H14O7 | 318 |

| 12 | 1H-Dibenzo[b,e][1,4]dioxepin-11-one,3,8-dihydroxy-4-(methoxymethyl)-1,6-dimethyl | C17H16O6 | 316 |

| 13 | Simplicildone A | C18H18O6 | 330 |

| Diketopiperazines | |||

| 14 | Cyclo-(Trp-Ala) | C14H15N3O2 | 257 |

| 15 | Cyclo-(Phe-Pro) | C14H16N2O2 | 244 |

| 16 | Cyclo-(Leu-Pro) | C11H18N2O2 | 210 |

| Indoles | |||

| 17 | 3-Indolacetic acid (3-IAA) | C10H9NO2 | 175 |

| 18 | 3-Indolcarboxylic acid (3-ICA) | C9H7NO2 | 161 |

| 19 | 3-Indolcarbaldehyde | C9H7NO | 145 |

| 20 | 3-Indolpropionic acid (3-IPA) | C11H11NO2 | 189 |

| 21 | 3-Indolbutyric acid (3-IBA) | C12H13NO2 | 203 |

| Jasmonates | |||

| 22 | Jasmonic acid (JA) | C12H18O3 | 210 |

| 23 | Methyl jasmonate | C13H20O3 | 224 |

| 24 | (11S)-11-Hydroxy-jasmonic acid | C12H18O4 | 226 |

| 25 | (11R)- 11-Hydroxy-jasmonic acid | C12H18O4 | 226 |

| 26 | 8-Hydroxy-jasmonic acid | C12H18O4 | 226 |

| 27 | 12-Hydroxy-jasmonic acid | C12H18O4 | 226 |

| 28 | 3-Oxo-2-(1-hydroxy-2Z-pentenyl)cyclopent-1-yl-butyric acid | C14H22O4 | 254 |

| 29 | 3-Oxo-2-(4-hydroxy-2Z-pentenyl)cyclopent-1-yl-butyric acid | C14H22O4 | 254 |

| 30 | JA–Glycine | C14H21NO4 | 267 |

| 31 | JA–Isoleucine | C18H29NO4 | 323 |

| 32 | JA–Serine | C15H23NO5 | 297 |

| 33 | JA–Threonine | C16H26NO5 | 311 |

| 34 | (+)-7-iso-Jasmonic acid | C12H18O3 | 210 |

| 35 | Ethyl (+)-7-iso-jasmonate | C14H22O3 | 238 |

| 36 | (+)-9,10-Dihydro-7-iso-jasmonic acid | C12H20O3 | 212 |

| 37 | (+)-4,5-Didehydro-7-iso-jasmonic acid | C12H16O3 | 208 |

| 38 | (+)-11,12-Didehydro-7-iso-jasmonic acid | C12H16O3 | 208 |

| 39 | (1R,2S)-[3-Oxo-2-(2Z)-pentenyl)-cyclopentyl]propanoic acid | C13H20O3 | 224 |

| 40 | (1S,2S)-[3-Oxo-2-(2Z)-pentenyl)-cyclopentyl]butanoic acid | C14H22O3 | 238 |

| 41 | (+)-Cucurbic acid | C12H20O3 | 212 |

| Lactones and Analogues | |||

| 42 | (3R,4S)-(-)-Botryodiplodin | C7H12O3 | 144 |

| 43 | (3S,4S)-3-epi-Botryodiplodin | C7H12O3 | 144 |

| 44 | (3S,4S)-4-Acetyl-3-methyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one | C7H10O3 | 142 |

| 45 | (3R,4S)-4-Acetyl-3-methyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one | C7H10O3 | 142 |

| 46 | (3S,4R,5R)-4-Hydroxymethyl-3,5-dimethyldihydro-2-furanone | C7H12O3 | 144 |

| 47 | Botryosphaerilactone A | C14H24O5 | 272 |

| 48 | Botryosphaerilactone B | C15H24O5 | 284 |

| 49 | Botryosphaerilactone C | C14H24O5 | 272 |

| 50 | Lasiolactol A | C14H26O5 | 274 |

| 51 | Lasiolactol B | C14H26O5 | 274 |

| 52 | (3S,4R)-3-Carboxy-2-methylene-heptan-4-olide | C9H12O4 | 184 |

| 53 | Decumbic acid | C9H12O4 | 184 |

| 54 | Lasiolactone/(R)-(-)-2-Octeno-δ-lactone | C8H12O2 | 140 |

| 55 | Tetrahydro-4-hydroxy-6-propylpyran-2-one | C8H14O3 | 158 |

| Lasiodiplodins | |||

| 56 | (3R)-Lasiodiplodin | C17H24O4 | 292 |

| 57 | (3R,4S)-4-Hydroxy-lasiodiplodin | C17H24O5 | 308 |

| 58 | (3R,5S)-5-Hydroxy-lasiodiplodin | C17H24O5 | 308 |

| 59 | (3R,5R)-5-Hydroxy-lasiodiplodin | C17H24O5 | 308 |

| 60 | (3R,6S)-6-Hydroxy-lasiodiplodin | C17H24O5 | 308 |

| 61 | Botryosphaeriodiplodin | C17H24O5 | 308 |

| 62 | (3R)-De-O-methyl-lasiodiplodin | C16H22O4 | 278 |

| 63 | (3R,4R)-4-Hydroxy-de-O-methyl-lasiodiplodin | C16H22O5 | 294 |

| 64 | (3R,5R)-5-Hydroxy-de-O-methyl-lasiodiplodin | C16H22O5 | 294 |

| 65 | (3R,6R)-6-Hydroxy-de-O-methyl-lasiodiplodin | C16H22O5 | 294 |

| 66 | (3R)-5-Oxo-Lasiodiplodin | C17H22O5 | 306 |

| 67 | (3R)-7-Oxo-Lasiodiplodin | C17H22O5 | 306 |

| 68 | (3R)-6-Oxo-de-O-methyl-lasiodiplodin | C16H20O5 | 292 |

| 69 | (3R,5E)-5-Etheno-lasiodiplodin | C17H22O4 | 290 |

| 70 | (3R,9E)-9-Etheno-lasiodiplodin | C17H22O4 | 290 |

| 71 | (3R,9E)-9-Etheno-de-O-methyl-lasiodiplodin | C16H20O4 | 276 |

| 72 | (R)-14-Methoxy-3-methyl-3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10-octahydro-1H-benzo[c][1]oxacyclododecine-1,11,12-trione | C17H22O5 | 306 |

| 73 | Lasiodiplactone | C24H34O5 | 402 |

| 74 | epi-8,9-Dihydrogreensporone C | C19H26O5 | 334 |

| 75 | (3R)-Nordinone | C18H24O5 | 320 |

| 76 | (R)-Zearalenone | C18H26O4 | 306 |

| 77 | Ethyl-2,4-dihydroxy-6-(8’-hydroxynonyl)benzoate | C18H28O5 | 324 |

| 78 | Isobutyl-2,4-dihydroxy-6-(8’-hydroxynonyl)benzoate | C20H32O5 | 352 |

| 79 | Ethyl-2,4-dihydroxy-6-(8’-oxononyl)benzoate | C18H26O5 | 322 |

| 80 | Ethyl-2,4-dihydroxy-6-nonylbenzoate | C18H28O4 | 308 |

| Melleins | |||

| 81 | (-)-Mellein | C10H10O3 | 178 |

| 82 | (-)-(3R)-5-Hydroxymellein | C10H10O4 | 194 |

| 83 | (-)-(3R,4S)-(trans)-4-Hydroxymellein | C10H10O4 | 194 |

| 84 | (-)-(3R,4R)-(cis)-4-Hydroxymellein | C10H10O4 | 194 |

| Phenyl and Phenol derivates | |||

| 85 | Tyrosol | C7H8O2 | 124 |

| 86 | 2-Phenylethanol | C7H8O | 108 |

| 87 | 6-Methylsalicylic acid | C8H8O3 | 152 |

| 88 | Scytalone | C10H10O4 | 194 |

| 2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones | |||

| 89 | 6-Hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone | C18H16O4 | 296 |

| 90 | 6,7-Dimethoxy-2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone | C19H18O4 | 310 |

| 91 | (5S,6R,7S,8R)-2-(2-Phenylethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrchromone | C17H20O6 | 320 |

| 92 | 6-Hydroxy-2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone | C17H14O3 | 266 |

| 93 | 4-Hydroxy-2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone | C17H14O3 | 266 |

| 94 | 6-Methoxy-2-phenethyl-4H-chromen-4-one | C18H16O3 | 280 |

| 95 | 6-Methoxy-2-(4-methoxyphenethyl)-4H-chromen-4-one | C19H18O4 | 310 |

| Phytohormones | |||

| 96 | Salicylic acid | C7H6O3 | 138 |

| 97 | Abscisic acid | C15H20O4 | 264 |

| 98 | Giberellic acid (GA3) | C19H22O6 | 346 |

| 99 | Zeatin | C10H13N5O | 219 |

| 100 | Zeatin riboside | C15H21N5O5 | 351 |

| Preussomerins | |||

| 101 | Chloropreussomerin A | C21H15ClO8 | 430 |

| 102 | Chloropreussomerin B | C22H17ClO8 | 444 |

| 103 | Preussomerin A | C20H14O7 | 366 |

| 104 | Preussomerin C | C21H16O8 | 396 |

| 105 | Preussomerin D | C20H12O7 | 364 |

| 106 | Preussomerin F | C20H12O7 | 364 |

| 107 | Preussomerin G | C20H10O7 | 362 |

| 108 | Preussomerin H | C20H12O7 | 364 |

| 109 | Preussomerin K | C20H12O8 | 380 |

| 110 | Preussomerin M | C21H16O8 | 396 |

| 111 | Ymf 1029 | C20H14O7 | 366 |

| Miscellaneous | |||

| 112 | Taxol | C47H51NO14 | 853 |

| 113 | Ergosterol | C28H44O | 396 |

| 114 | 2,4,6-Trimethyloct-2-enoic acid 1,2,6,8a-tetrahydro-7-hydroxy-1,8a-dimethyl-6-oxo-2-naphtalenyl ester, | C23H32O4 | 372 |

| 115 | Botryosphaeridione | C12H12O3 | 204 |

| 116 | Botryosphaerihydrofuran | C14H18O2 | 218 |

| 117 | Botryosphaerinone | C12H18O3 | 210 |

| 118 | Cladospirone B | C20H16O5 | 336 |

| 119 | Cholestanol glucoside | C33H56O6 | 548 |

| Strain | Source (Lifestyle) | Growth Conditions | Identified Compounds * | Bioactivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulolytic strain | - | PDB shaken, 8 d, 30 °C | 42 | Antibacterial | [24] |

| - | - | Czapek medium | 18,19,22,56,62,81,84 | - | [25] |

| D 7/2 | Citrus sinensis | Medium (sucrose, soya flour, corn steep liquor, mineral salts), 7 d, 30 °C | 24–29,34–41 | - | [26,27,28] |

| - | - | Czapek medium (0.1% yeast extract), 15 d, 26 °C | 22 | Phytotoxic | [29] |

| IFO 31059 | - | Potato–sucrose medium, 30 d, 23 °C | 1,22,23,81 | Potato microtuber induction | [30] |

| GK-1 | Cocos nucifera (endophyte) | Potato dextrose agar (PDA), 15 d, 25 °C | 54,81,86 | - | [31] |

| IFO 31059 | - | Potato–sucrose medium (2%), 35 d, 23 °C | 58,59,66 | Potato microtuber induction | [32] |

| IFO 31059 (mycelium) | - | Potato–sucrose medium (3%), 35 d, 25 °C | 57,64,65,77,78 | Potato microtuber induction | [33,34] |

| - | Mangifera indica (pathogen) | Surface-sterilized bananas, 3 d, 25 °C | 52,53 | Phytotoxic | [23] |

| Potato–glucose, 21 d, 25 °C | 52 | ||||

| Shimokita 2 | Mangifera indica | Potato–sucrose medium (3% sucrose) 21 d, 25 °C | 60 | Potato microtuber induction | [35] |

| ZZF36 | Sargassum sp. (endophyte) | - | 56,62,64,68,70 | Antimicrobial | [36] |

| - | Psidium guajava (pathogen) | Rice, 32 d, room temperature | 113 | - | [37] |

| Czapek, 40 d, room temperature | 84,114 | ||||

| OCS71 | - | Potato dextrose broth (PDB, 2%), 21 d, 25 °C | 2,5 | Potato microtuber induction | [38] |

| BT 115 | Taxus baccata (endophyte) | - | 112 | [39] | |

| OCS71 | - | PDB (2%), 14 d, 25 °C | 1,3,4,6 | - | [40] |

| PSU-M114 | Garcinia mangostana (endophyte) | PDB, 21 d, room temperature | 54–56,58,59,61,81–84,87,117 | Antibacterial | [41] |

| PSU-M35 | Garcinia mangostana (endophyte) | PDB, 21 d, room temperature | 44,46–49,115,116 | Antibacterial | [41] |

| - | Bidens Pilosa (endophyte) | M25, 21 d, 23 °C | 7–10,18 | Antimicrobial, antiproliferative, cytotoxic | [42] |

| - | Morinda citrifolia (endophyte) | MID with soytone (1 g), 22 d | 112 | Cytotoxic | [43] |

| 2334 | Citrus sinensis | Medium (sucrose, mineral salts and yeast extract), 10 d, 30 °C | 17,20–22,30–33,96–100 | - | [44] |

| 1517 | Citrus sinensis | Medium (sucrose, mineral salts and yeast extract), 10 d, 30 °C | 17,20–22,30–33,96–100 | - | [44] |

| 83 | Brazilian wood | Medium (Sucrose, mineral salts and yeast extract), 10 d, 30 °C | 17,20–22,30–33,96–100 | - | [44] |

| - | Mapania kurzii (endophyte) | PDA | 62,63,65,68,71 | [45] | |

| ZJ-HQ1 | Acanthus ilicifolius | Rice solid-substrate medium+artificial sea salt solution (3%), 28 d, room temperature | 101–111 | Cytotoxic, Antibacterial | [15] |

| UCD256Ma | Vitis vinifera | 5% glucose, 20 d, 25 °C | 81, fatty acids (Table 3) | Tobacco seed germination | [22] |

| MXL28 | Vitis vinifera | Oatmeal powder, 60 d, room temperature | 81, fatty acids (Table 3) | Tobacco seed germination | [22] |

| - | Saraca asoca (endophyte) | M1D broth, 3 d, 25 °C | 119 | Cytotoxic activity against human cancer lines, antioxidant activity | [46] |

| 318# | Excoecaria agallocha (endophyte) | Rice solid-substrate medium, 28 d, 28 °C | 56,58,59,62,67,69,72,74, 76,77,79,80 | Cytotoxic activity against human cancer lines | [18,47] |

| ZJ-HQ1 | Acanthus ilicifolius (endophyte) | Rice solid-substrate medium+artificial sea salt solution (3%), 28 d, room temperature | 73 | Anti-inflammatory | [17] |

| SNFF | Solanum nigrum (endophyte) | Liquid malt extract medium, 28 d, 20 °C | 15,16,19 | - | [48] |

| VP 01 | Vitex pinnata (endophyte) | Rice solid medium, 30 d, room temperature | 62,81,118 | Anti-trypanosomal | [49] |

| A13 | Aquilaria sinensis (endophyte) | Saw dust of host plant with 60% moisture content, 38 d, 27 °C | 89–95 | - | [50] |

| CAA019 | Cocos nucifera (pathogen) | Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 25 °C | 18,22,56 | Phytotoxic, cytotoxic | [19] |

| Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 37 °C | 18,22,44–47 | ||||

| CBS339.90 | Human (pathogen) | Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 25 °C | 18,22,83,84,88 | Phytotoxic, cytotoxic | [19] |

| Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 37 °C | 14,18,44–47,83,84 | ||||

| LA-SOL3 | Vitis vinifera (pathogen) | Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 25 °C | 18,22,45,46,50,51,85 | Phytotoxic, cytotoxic | [13] |

| Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 37 °C | 18,42–46,50,51,84,85 | ||||

| LA-SV1 | Vitis vinifera (pathogen) | Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 25 °C | 18,22,45,46,50,51,81,84 | Phytotoxic, cytotoxic | [13] |

| Czapek amended with cornmeal, 21 d, 37 °C | 18,42,43,45,46,50,51,80,85 | ||||

| M4.2-2 | Mangrove sediment | Rice medium, 25 d, room temperature | 7,8,10–13,62,75,81 | Antibacterial, cytotoxic | [51] |

| Fatty Acids and Their Esters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | L. theobromae UCD256Ma [22] | L. theobromae MXL28 [22] | L. theobromae CBS 122127 [72] | L. theobromae CBS 2334 [72] | |||

| Growth Condition | Oatmeal Powder, 60d, Room Temperature | 5% Glucose, 20 d, 25 °C | 5% Oil, 20 d, 25 °C | 5% Oil + 5% Glucose, 20 d, 25 °C | Oatmeal Powder, 60 d, Room Temperature | Czapek-Dox Medium, 10–12 d 27 °C (Mycelium) | Czapek-Dox Medium, 10–12 d, 27 °C (Mycelium) |

| Hexadecenoic acid (C16:1n7) | + | + | |||||

| Methyl hexadecanoate (C16:0 ME) | + | + | + | ||||

| Ethyl hexadecanoate (C16:0 EE) | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Hexadecanoate, 2-methylpropyl ester | + | + | |||||

| Octadecanoic acid (C18:0) | + | ||||||

| 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z) (C18:1n9) | + | ||||||

| 9-Octadecenoate (Z)- methyl ester (C18:1n9 ME) | + | + | + | ||||

| Octadecanoate ethyl ester (C18:0 EE) | + | + | + | + | |||

| 9-Octadecenoate (Z), ethyl ester (C18:1n9 EE) | + | + | + | + | |||

| 9-Octadecenoate (E) ethyl ester (C18:1n9 EE) | + | + | + | ||||

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z) (C18:1n9) | + | + | |||||

| 9,12-Octadecadienoate (Z,Z)-, methyl ester (C18:1n9 ME) | + | + | + | + | |||

| 9,12-Octadecadienoate (Z,Z) ethyl Ester (C18:1n9 EE) | + | + | + | + | |||

| 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoate (Z,Z,Z)-ethyl ester) (C18:3n3 EE) | + | + | + | + | |||

| Eicosanoic acid (C20:0) | + | ||||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salvatore, M.M.; Alves, A.; Andolfi, A. Secondary Metabolites of Lasiodiplodia theobromae: Distribution, Chemical Diversity, Bioactivity, and Implications of Their Occurrence. Toxins 2020, 12, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12070457

Salvatore MM, Alves A, Andolfi A. Secondary Metabolites of Lasiodiplodia theobromae: Distribution, Chemical Diversity, Bioactivity, and Implications of Their Occurrence. Toxins. 2020; 12(7):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12070457

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalvatore, Maria Michela, Artur Alves, and Anna Andolfi. 2020. "Secondary Metabolites of Lasiodiplodia theobromae: Distribution, Chemical Diversity, Bioactivity, and Implications of Their Occurrence" Toxins 12, no. 7: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12070457

APA StyleSalvatore, M. M., Alves, A., & Andolfi, A. (2020). Secondary Metabolites of Lasiodiplodia theobromae: Distribution, Chemical Diversity, Bioactivity, and Implications of Their Occurrence. Toxins, 12(7), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12070457