Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease?

Abstract

1. Introduction

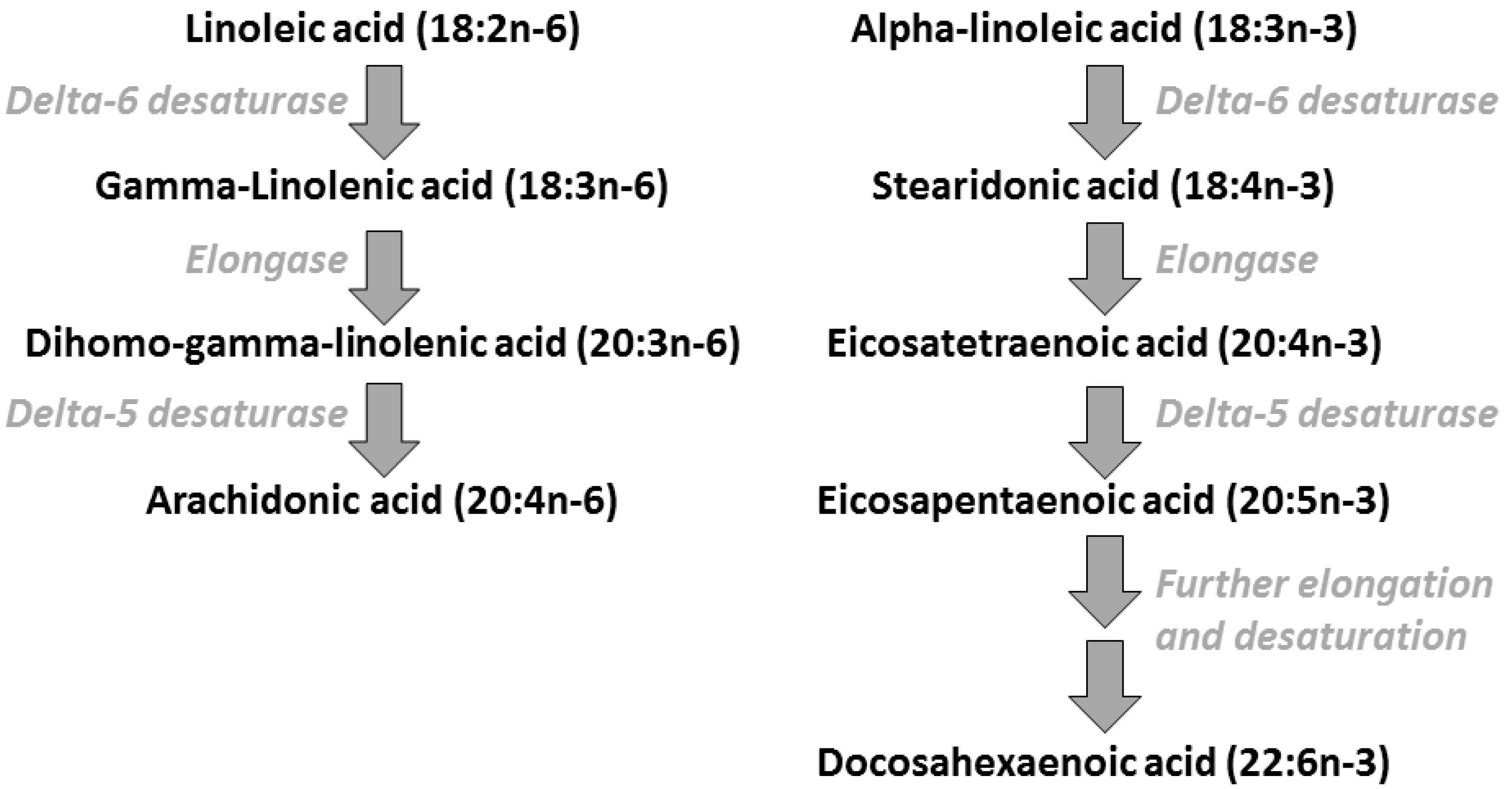

2. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Metabolic Relationships, Dietary Sources, and Typical Intakes

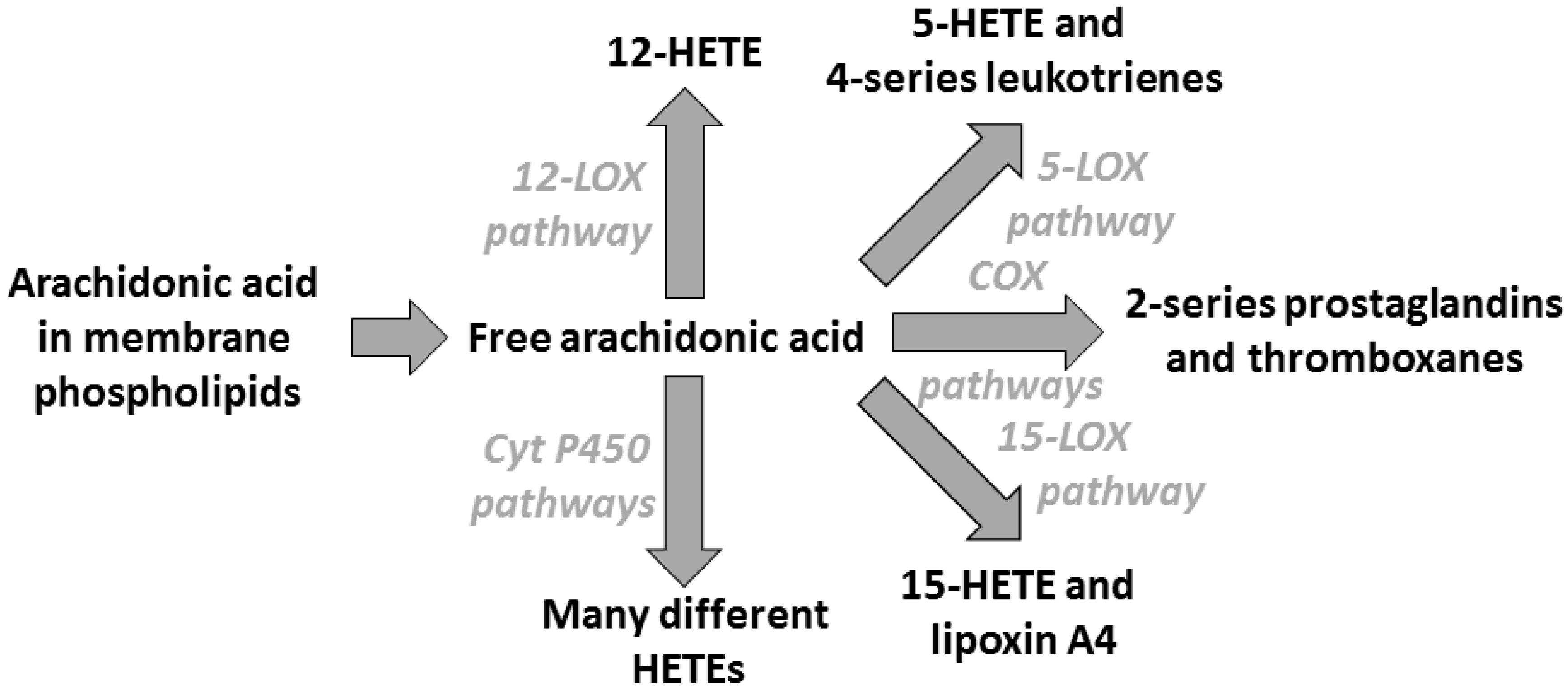

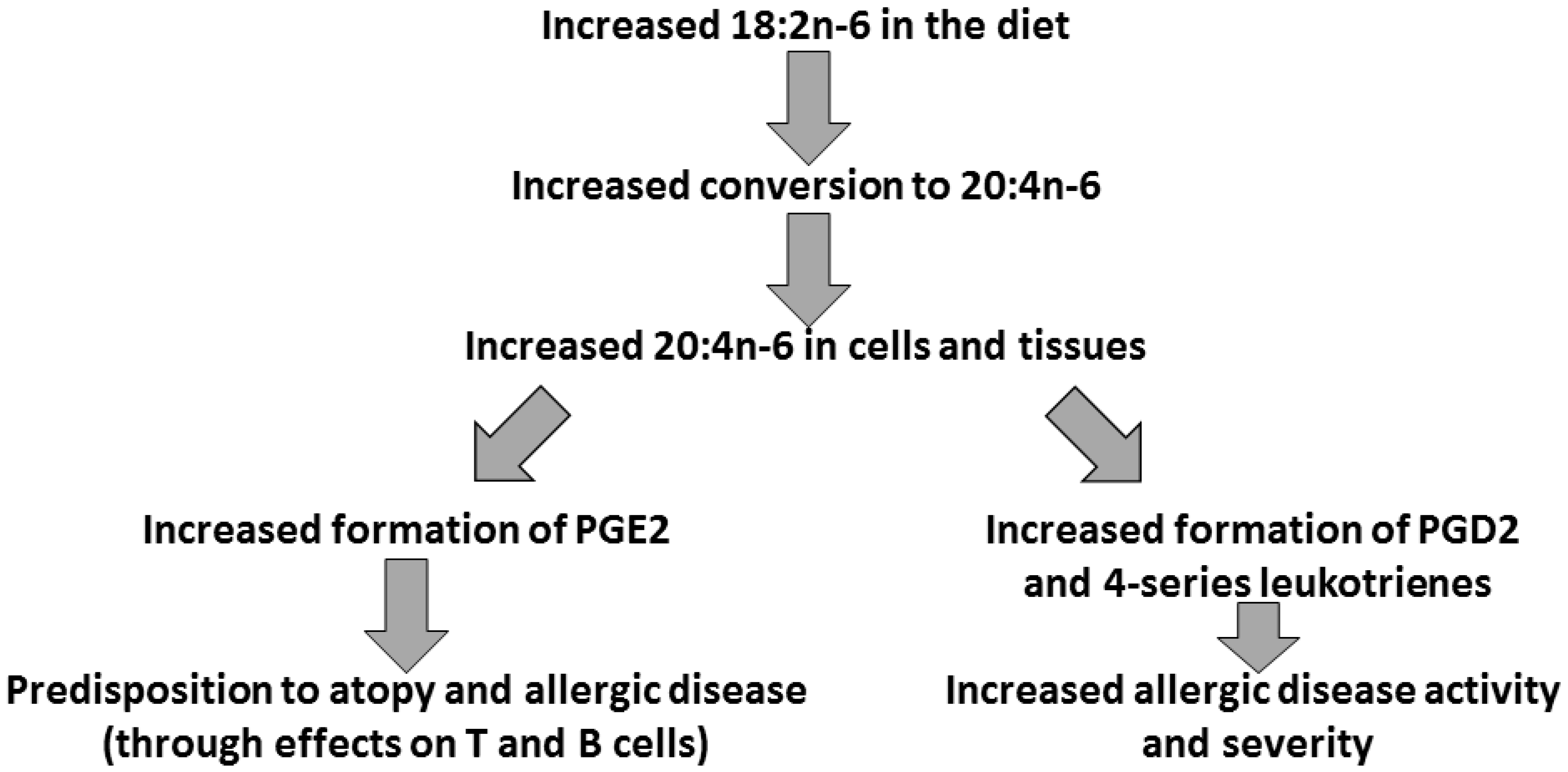

3. Arachidonic Acid, Lipid Mediators, Inflammation, and Allergic Disease

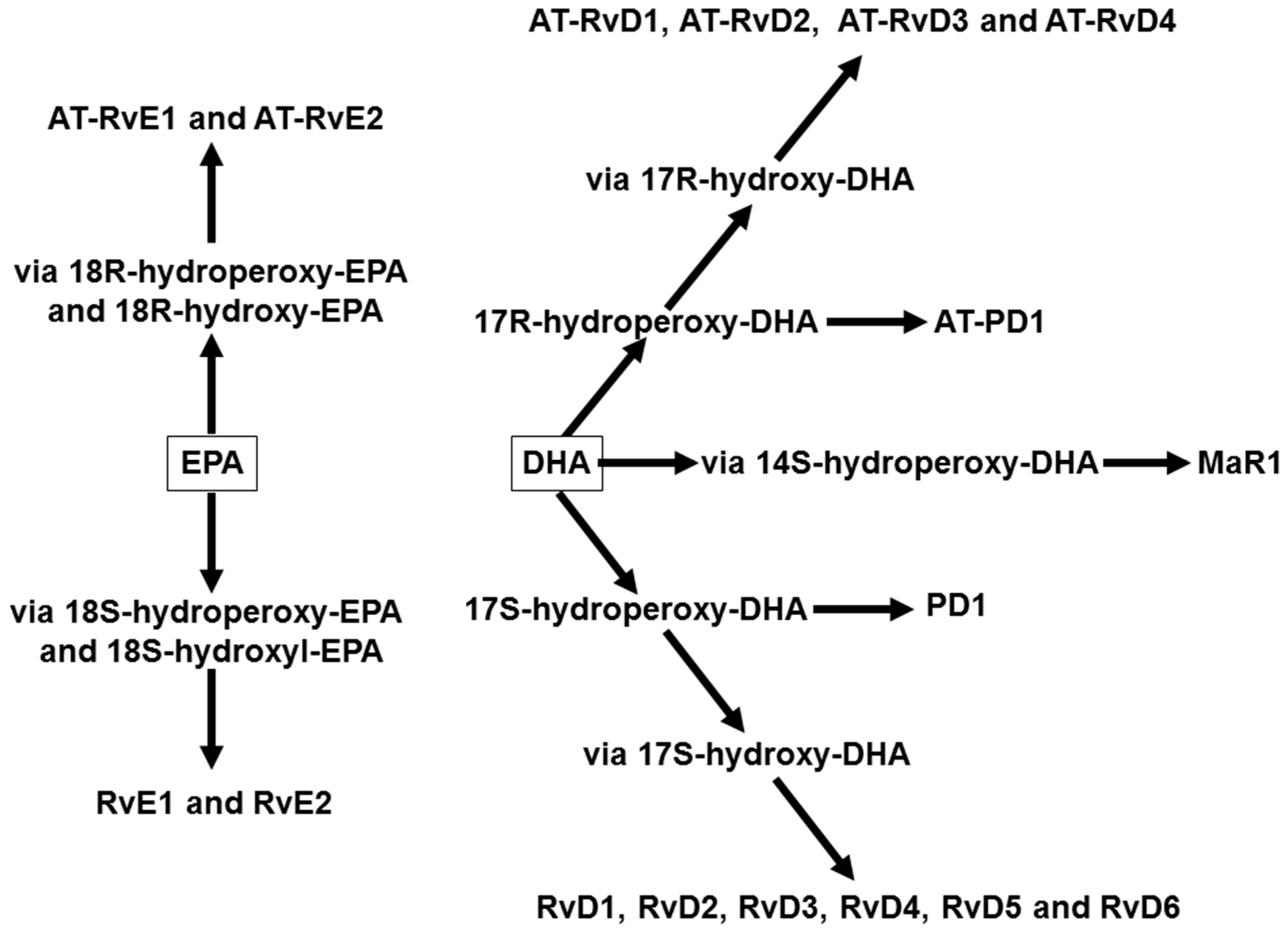

4. Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Lipid Mediators, and Inflammatory Processes

5. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Allergic Disease in Infants and Children

6. The Salmon in Pregnancy Study

7. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| ALA | α-Linolenic acid |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LA | Linoleic acid |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| LT | Leukotriene |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| TX | Thromboxane |

References

- Barker, D.J. The developmental origins of adult disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004, 23, 588S–595S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Cooper, C.; Thornburg, K.L. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.A. Nutrients, growth, and the development of programmed metabolic function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000, 478, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Langley-Evans, S.C. Nutrition in early life and the programming of adult disease: A review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28 (Suppl. 1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zusman, I.; Gurevich, P.; Ben-Hur, H. Two secretory immune systems (mucosal and barrier) in human intrauterine development, normal and pathological. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 16, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, O. Innate immunity of the newborn: Basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.K.; Hollander, G.A.; McMichael, A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282, 2014–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C.; Krauss-Etschmann, S.; de Jong, E.C.; Dupont, C.; Frick, J.-S.; Frokiaer, H.; Garn, H.; Koletzko, S.; Lack, G.; Mattelio, G.; et al. Workshop report: Early nutrition and immunity—Progress and perspectives. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hodge, L.; Peat, J.; Salome, C. Increased consumption of polyunsaturated oils may be a cause of increased prevalence of childhood asthma. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1994, 24, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, P.N.; Sharp, S. Dietary fat and asthma: Is there a connection? Eur. Resp. J. 1997, 10, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Kremmyda, L.S.; Vlachava, M.; Noakes, P.S.; Miles, E.A. Is there a role for fatty acids in early life programming of the immune system? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasbalg, T.L.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Ramsden, C.E.; Majchrzak, S.F.; Rawlings, R.R. Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Nutrition Foundation. Briefing Paper: N-3 Fatty Acids and Health; British Nutrition Foundation: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoob, P.; Calder, P.C. Fatty acids and immune function: New insights into mechanisms. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, S41–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Immunomodulation by omega-3 fatty acids. Prostagland Leukotr. Essent. Fatty Acids 2007, 77, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. The relationship between the fatty acid composition of immune cells and their function. Prostagland Leukotr. Essent. Fatty Acids 2008, 79, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C.; Miles, E.A. Fatty acids and atopic disease. Pediat. Allergy Immunol. 2000, 11 (Suppl. 13), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Abnormal fatty acid profiles occur in atopic dermatitis but what do they mean? Clin. Exp. Allergy 2006, 36, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaou, A. Prostanoids. In Bioactive Lipids; Nicolaou, A., Kafatos, G., Eds.; The Oily Press: Bridgewater, UK, 2004; pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, S. Leukotrienes and lipoxins. In Bioactive Lipids; Nicolaou, A., Kafatos, G., Eds.; The Oily Press: Bridgewater, UK, 2004; pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.A.; Austen, K.F.; Soberman, R.J. Leukotrienes and other products of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway: Biochemistry and relation to pathobiology in human diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tilley, S.L.; Coffman, T.M.; Koller, B.H. Mixed messages: Modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinski, P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.L.; Peebles, R.S. Update on the role of prostaglandins in allergic lung inflammation: Separating friends from foes, harder than you might think. J. Allegy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.Y.; Christman, J.W. Involvement of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandins in the molecular pathogenesis of inflammatory lung diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006, 290, L797–L805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajt, M.L.; Gelhaus, S.L.; Freeman, B.; Uvalle, C.E.; Trudeau, J.B.; Holgun, F.; Wenzel, S.E. Prostaglandn D2 pathway upregulation: Relation to asthma severity, control, and TH2 inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.D.; Clish, C.B.; Schmidt, B.; Gronert, K.; Serhan, C.N. Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: Signals in resolution. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachier, I.; Chanez, P.; Bonnans, C.; Godard, P.; Bousquet, J.; Chavis, C. Endogenous anti-inflammatory mediators from arachidonate in human neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 290, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Jain, A.; Marleau, S.; Clish, C.; Kantarci, A.; Behbehani, B.; Colgan, S.P.; Stahl, G.L.; Merched, A.; Petasis, N.A.; et al. Reduced inflammation and tissue damage in transgenic rabbits overexpressing 15-lipoxygenase and endogenous anti-inflammatory lipid mediators. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 6856–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewirtz, A.T.; Collier-Hyams, L.S.; Young, A.N.; Kucharzik, T.; Guilford, W.J.; Parkinson, J.F.; Williams, I.R.; Neish, A.S.; Madara, J.L. Lipoxin A4 analogs attenuate induction of intestinal epithelial proinflammatory gene expression and reduce the severity of dextran sodium sulfate induced colitis. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 5260–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Mutius, E.; Martinez, F.D.; Fritzsch, C.; Nicolai, T.; Roell, G.; Thiemann, H.H. Prevalence of asthma and atopy in two areas of West and East Germany. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1994, 149, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poysa, L.; Korppi, M.; Pietikainen, M.; Remes, K.; Juntunen-Backman, K. Asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema in finnish children and adolescents. Allergy 1991, 46, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Mutius, E.; Weiland, S.K.; Fritzsch, C.; Duhme, H.; Keil, U. Increasing prevalence of hay fever and atopy among children in Leipzig, East Germany. Lancet 1998, 351, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunder, T.; Kuikka, L.; Turtinen, J.; Rasanen, L.; Uhari, M. Diet, serum fatty acids, and atopic diseases in childhood. Allergy 2001, 56, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haby, M.M.; Peat, J.K.; Marks, G.B.; Woolcock, A.J.; Leeder, S.R. Asthma in preschool children: Prevalence and risk factors. Thorax 2001, 56, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolte, G.; Frye, C.; Hoelscher, B.; Meyer, I.; Wjst, M.; Heinrich, J. Margarine consumption and allergy in children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.L.; Elfman, L.; Mi, Y.; Johansson, M.; Smedje, G.; Norback, D. Current asthma and respiratory symptoms among pupils in relation to dietary factors and allergens in the school environment. Indoor Air 2005, 15, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddy, W.H.; de Klerk, N.H.; Kendall, G.E.; Mihrshahi, S.; Peat, J.K. Ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids and childhood asthma. J. Asthma 2004, 41, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala-Vila, A.; Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Fatty acid composition abnormalities in atopic disease: Evidence explored and role in the disease process examined. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2008, 38, 1432–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwaru, B.I.; Erkkola, M.; Lumia, M.; Kronberg-Kippilä, C.; Ahonen, S.; Kaila, M.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; Knip, M.; Veijola, R.; et al. Maternal intake of fatty acids during pregnancy and allergies in the offspring. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, P.; Pala, H.S.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Newsholme, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Encapsulated fish oil enriched in α-tocopherol alters plasma phospholipid and mononuclear cell fatty acid compositions but not mononuclear cell functions. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 30, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, D.A.; Wallace, F.A.; Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C.; Newsholme, P. The effect of low to moderate amounts of dietary fish oil on neutrophil lipid composition and function. Lipids 2000, 35, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, D.; Miles, E.A.; Banerjee, T.; Wells, S.J.; Roynette, C.E.; Wahle, K.W.J.W.; Calder, P.C. Dose-related effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on innate immune function in healthy humans: A comparison of young and older men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Browning, L.M.; Walker, C.G.; Mander, A.P.; West, A.L.; Madden, J.; Gambell, J.M.; Young, S.; Wang, L.; Jebb, S.A.; Calder, P.C. Incorporation of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids into lipid pools when given as supplements providing doses equivalent to typical intakes of oily fish. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, C.G.; West, A.L.; Browning, L.M.; Madden, J.; Gambell, J.M.; Jebb, S.A.; Calder, P.C. The pattern of fatty acids displaced by EPA and DHA following 12 Months supplementation varies between blood cell and plasma fractions. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6281–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1505S–1519S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wada, M.; DeLong, C.J.; Hong, Y.H.; Rieke, C.J.; Song, I.; Sidhu, R.S.; Yuan, C.; Warnock, M.; Schmaier, A.H.; Yokoyama, C.; et al. Enzymes and receptors of prostaglandin pathways with arachidonic acid-derived versus eicosapentaenoic acid-derived substrates and products. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 22254–22266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannenberg, G.; Serhan, C.N. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators in the inflammatory response: An update. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 2010, 1801, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; van Dyke, T.E. Resolving inflammation: Dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N. Resolution phase lipid mediators of inflammation: Agonists of resolution. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013, 13, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Z.B.; Ge, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cluette-Brown, J.; Laposata, M.; Leaf, A.; Kang, J.X. Adenoviral gene transfer of Caenorhabditis elegans n-3 fatty acid desaturase optimizes fatty acid composition in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4050–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, S.; Haworth, O.; Wu, L.; Weylandt, K.H.; Levy, B.D.; Kang, J.X. Fat-1 transgenic mice with elevated omega-3 fatty acids are protected from allergic airway responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 2011, 1812, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, H.; Hisada, T.; Ishizuka, T.; Utsugi, M.; Kawata, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Okajima, F.; Dobashi, K.; Mori, M. Resolvin E1 dampens airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 367, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, O.; Cernadas, M.; Yang, R.; Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvin E1 regulates interleukin 23, interferon-gamma and lipoxin A4 to promote the resolution of allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerio, A.P.; Haworth, O.; Croze, R.; Oh, S.F.; Uddin, M.; Carlo, T.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Priluck, R.; Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvin D1 and aspirin triggered resolvin D1 promote resolution of allergic airways responses. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremmyda, L.-S.; Vlachava, M.; Noakes, P.S.; Diaper, N.D.; Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Atopy risk in infants and children in relation to early exposure to fish, oily fish, or long-chain omega-3 fatty acids: A systematic review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 41, 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-Q.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Luo, C.-Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.-L.; Sinha, A.; Li, Z.-Y. Fish intake during pregnancy or infancy and allergic outcomes in children: Asystematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 28, 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lumia, M.; Luukkainen, P.; Tapanainen, H.; Kaila, M.; Erkkola, M.; Uusitalo, L.; Niinistö, S.; Kenward, M.G.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; et al. Dietary fatty acid composition during pregnancy and the risk of asthma in the offspring. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 22, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Ohfuji, S.; Hirota, Y. Maternal fat consumption during pregnancy and risk of wheeze and eczema in Japanese infants aged 16–24 months: The Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Thorax 2009, 64, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, K.C.; Calder, P.C.; Inskip, H.M.; Robinson, S.M.; Roberts, G.C.; Cooper, C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Lucas, J.S.A. Maternal plasma phosphatidylcholine fatty acids and atopy and wheeze in the offspring at age of 6 years. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 474–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan, J.A.; Mori, T.A.; Barden, A.; Beilin, L.J.; Taylor, A.L.; Holt, P.G.; Prescott, S.L. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy modifies neonatal allergen-specific immune responses and clinical outcomes in infants at high risk of atopy: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 112, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, S.F.; Osterdal, M.L.; Salvig, J.D.; Mortensen, L.M.; Rytter, D.; Secher, N.J.; Henriksen, T.B. Fish oil intake compared with olive oil intake in late pregnancy and asthma in the offspring: 16 y of registry-based follow-up from a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Strøm, M.; Maslova, E.; Dahl, R.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Rytter, D.; Bech, B.H.; Henriksen, T.B.; Granström, C.; Halldorsson, T.I.; et al. Fish oil supplementation during pregnancy and allergic respiratory disease in the adult offspring. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuhjelm, C.; Warstedt, K.; Larsson, J.; Fredriksson, M.; Böttcher, M.F.; Fälth-Magnusson, K.; Duchén, K. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy and lactation may decrease the risk of infant allergy. Acta Paediatr. 2009, 98, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuhjelm, C.; Warstedt, K.; Fagerås, M.; Fälth-Magnusson, K.; Larsson, J.; Fredriksson, M.; Duchén, K. Allergic disease in infants up to 2 years of age in relation to plasma omega-3 fatty acids and maternal fish oil supplementation in pregnancy and lactation. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 22, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, D.J.; Sullivan, T.; Gold, M.S.; Prescott, S.L.; Heddle, R.; Gibson, R.A.; Makrides, M. Effect of n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in pregnancy on infants' allergies in first year of life: Randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 2012, 344, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, D.J.; Sullivan, T.; Gold, M.S.; Prescott, S.L.; Heddle, R.; Gibson, R.A.; Makrides, M. Randomized controlled trial of fish oil supplementation in pregnancy on childhood allergies. Allergy 2013, 68, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, K.P.; Sullivan, T.; Palmer, D.; Gold, M.; Kennedy, D.J.; Martin, J.; Makrides, M. Prenatal fish oil supplementation and allergy: 6-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisgaard, H.; Stokholm, J.; Chawes, B.L.; Vissing, N.H.; Bjarnadóttir, E.; Schoos, A.M.; Wolsk, H.M.; Pedersen, T.M.; Vinding, R.K.; Thorsteinsdóttir, S.; et al. Fish oil-derived fatty acids in pregnancy and wheeze and asthma in offspring. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2530–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss-Etschmann, S.; Hartl, D.; Rzehak, P.; Heinrich, J.; Shadid, R.; del Carmen Ramírez-Tortosa, M.; Campoy, C.; Pardillo, S.; Schendel, D.J.; Decsi, T.; et al. Nutraceuticals for Healthier Life Study Group. Decreased cord blood IL-4, IL-13, and CCR4 and increased TGF-beta levels after fish oil supplementation of pregnant women. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan, J.A.; Mori, T.A.; Barden, A.; Beilin, L.J.; Taylor, A.L.; Holt, P.G.; Prescott, S.L. Maternal fish oil supplementation in pregnancy reduces interleukin-13 levels in cord blood of infants at high risk of atopy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2003, 33, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; Barden, A.E.; Mori, T.A.; Dunstan, J.A. Maternal fish oil supplementation in pregnancy modifies neonatal leukotriene production by cord-blood-derived neutrophils. Clin. Sci. 2006, 113, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denburg, J.A.; Hatfield, H.M.; Cyr, M.M.; Hayes, L.; Holt, P.G.; Sehmi, R.; Dunstan, J.A.; Prescott, S.L. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy modifies neonatal progenitors at birth in infants at risk of atopy. Pediatr. Res. 2005, 57, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warstedt, K.; Furuhjelm, C.; Duchen, K.; Falth-Magnusson, K.; Fageras, M. The effects of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in pregnancy on maternal eicosanoid, cytokine, and chemokine secretion. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, K.P.; Gold, M.; Kennedy, D.; Martin, J.; Makrides, M. Omega-3 long-chain PUFA intake during pregnanacy and allergic disease outcomes in the offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritzen, L.; Kjaer, T.M.R.; Fruekilde, M.B.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Frokiaer, H. Fish oil supplementation of lactating mothers affects cytokine production in 2 1/2-year-old children. Lipids 2005, 40, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Vaz, N.; Meldrum, S.J.; Dunstan, J.A.; Lee-Pullen, T.F.; Metcalfe, J.; Holt, B.J.; Serralha, M.; Tulic, M.K.; Mori, T.A.; Prescott, S.L. Fish oil supplementation in early infancy modulates developing infant immune responses. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Vaz, N.; Meldrum, S.J.; Dunstan, J.A.; Martino, D.; McCarthy, S.; Metcalfe, J.; Tulic, M.K.; Mori, T.A.; Prescott, S.A. Postnatal fish oil supplementation in high-risk infants to prevent allergy: Randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Peat, J.K.; Marks, G.B.; Mellis, C.M.; Tovey, E.R.; Webb, K.; Britton, W.J.; Leeder, S.R. Childhood Asthma Prevention Study. Eighteen-month outcomes of house dust mite avoidance and dietary fatty acid modification in the Childhood Asthma Prevention Study (CAPS). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Peat, J.K.; Webb, K.; Oddy, W.; Marks, G.B.; Mellis, C.M. Effect of omega-3 fatty acid concentrations in plasma on symptoms of asthma at 18 months of age. Pediatr. Allergy. Immunol. 2004, 15, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peat, J.K.; Mihrshahi, S.; Kemp, A.S.; Marks, G.B.; Tovey, E.R.; Webb, K.; Mellis, C.M.; Leeder, S.R. Three-year outcomes of dietary fatty acid modification and house dust mite reduction in the Childhood Asthma Prevention Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 114, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, G.B.; Mihrshahi, S.; Kemp, A.S.; Tovey, E.R.; Webb, K.; Almqvist, C.; Ampon, R.D.; Crisafulli, D.; Belousova, E.G.; Mellis, C.M.; et al. Prevention of asthma during the first 5 years of life: A randomized controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almqvist, C.; Garden, F.; Xuan, W.; Mihrshahi, S.; Leeder, S.R.; Oddy, W.; Webb, K.; Marks, G.B.; CAPS team. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid exposure from early life does not affect atopy and asthma at age 5 years. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, 1438–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SACN/COT (Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition/Committee on Toxicity). Advice on Fish Consumption: Benefits and Risks; TSO: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, E.A.; Noakes, P.S.; Kremmyda, L.S.; Vlachava, M.; Diaper, N.D.; Rosenlund, G.; Urwin, H.; Yaqoob, P.; Rossary, A.; Farges, M.C.; et al. The Salmon in Pregnancy Study: Study design, subject characteristics, maternal fish and marine n-3 fatty acid intake, and marine n-3 fatty acid status in maternal and umbilical cord blood. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1986S–1992S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al, M.D.; van Houwelingen, A.C.; Kester, A.D.; Hasaart, T.H.; de Jong, A.E.; Hornstra, G. Maternal essential fatty acid patterns during normal pregnancy and their relationship to the neonatal essential fatty acid status. Br. J. Nutr. 1995, 74, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, S.J.; Houwelingen, A.C.; Antal, M.; Manninen, A.; Godfrey, K.; López-Jaramillo, P.; Hornstra, G. Maternal and neonatal essential fatty acid status in phospholipids: An international comparative study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 51, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noakes, P.S.; Vlachava, M.; Kremmyda, L-S.; Diaper, N.D.; Miles, E.A.; Erlewyn-Lajeunesse, M.; Williams, A.P.; Godfrey, K.M.; Calder, P.C. Increased intake of oily fish in pregnancy: Effects on neonatal immune responses and on clinical outcomes in infants at 6 months. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urwin, H.J.; Miles, E.A.; Noakes, P.S.; Kremmyda, L.S.; Vlachava, M.; Diaper, N.D.; Pérez-Cano, F.J.; Godfrey, K.M.; Calder, P.C.; Yaqoob, P. Salmon consumption during pregnancy alters fatty acid composition and secretory IgA concentration in human breast milk. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Publication | Particpants | Intervention Details | Outcomes | Differences from Control in n-3 PUFA Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunstan et al. [62] | atopic, non-smoking pregnant women (n = 98) | fish oil providing 3.7 g n-3 PUFAs daily including 1.02 g EPA and 2.07 g DHA; control group received olive oil; from 20 weeks of gestation until delivery | skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; peanut; house dust mite; cat), asthma, atopic eczema, food allergy all at 12 months of life | less sensitisation to hens’ egg (odds ratio 0.34; p = 0.05); less severe atopic eczema (odds ratio 0.09; p = 0.045); less recurrent wheeze, persistant cough and diagnosed asthma but these were not significant |

| Olsen et al. [63] | pregnant women; n = 553 | fish oil providing 2.7 g n-3 PUFAs daily including 0.86 g EPA and 0.62 g DHA; control group received olive oil; a third group received no intervention; from 30 weeks of gestation until delivery | asthma-related diagnoses at 16 years of life | less incidence of “any asthma” (3.04% vs 8.08%; p = 0.03) and “allegic asthma” (0.76% vs. 5.88%; p = 0.01) |

| Hansen et al. [64] | as above | as above | prescription of asthma or allergic rhinitis medication at age 24 years | less prescription of asthma medication (hazard ratio 0.54; p = 0.02); trend to less prescription of allerfgic rhinitis medication (hazard ratio 0.70; p = 0.10) |

| Furuhjelm et al. [65] | pregnant women with fetus at high allergic risk; n = 145 | fish oil providing 2.7 g n-3 PUFAs daily including 1.6 g EPA and 1.1 g DHA; control group received soybean oil; from 25 weeks of gestation until 3.5 months post-natally | skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; wheat), IgE-antibodies (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; wheat), food allergy, eczema at 3, 6 and 12 months of life | less IgE-associated eczema up to 6 months of life (8% vs. 20%; p = 0.06); less IgE-associated eczema (7.7% vs. 20.8%; p = 0.02), sensitisation to hens’ egg (11.5% vs. 25.4%; p = 0.02), any positive skin prick test (15,4% vs. 31.7%; p = 0.04) up to 12 months of life |

| Furuhjelm et al. [66] | as above | as above | skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; wheat; cat; tomothy; birch), food allergy, eczema at 24 months of life | less IgE-mediated disease (11.1% vs. 30.6%; p = 0.01), IgE-mediated food reactions (5.6% vs. 21.5%; p = 0.01), sensitisation to hens’ egg (13.4% vs. 29.5%; p = 0.04), any positive skin prick test (19.2% vs. 36.1%; p = 0.048), IgE-associated eczema (9.3% vs. 23.8%; p = 0.04) up to 24 months of life |

| Palmer et al. [67] | pregnant women with fetus at high atopy risk; n = 706 | fish oil providing 0.9 g n-3 PUFAs daily including 0.1 g EPA and 0.8 g DHA; control group received mixed vegetable oils; from 21 weeks of gestation until delivery | skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; peanut; wheat; tuna; grass pollen; perennial ryegrass; olive tree pollen; Alternaria tenuis; cat; house dust mite), asthma, food allergy, eczema at 12 months of life | less sensitisation to hens’ egg (9% vs. 15%; p = 0.02); less IgE-associated eczema (7% vs. 12%; p = 0.06) |

| Palmer et al. [68] | as above | as above | skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; peanut; wheat; tuna; cashew; sesame; grass pollen; perennial ryegrass; olive tree pollen; alternaria tenuis; cat; house dust mite), asthma, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, eczema at 3 years of life | - |

| Best et al. [69] | as above | as above | skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; peanut; cashew; perennial ryegrass pollen; olive tree pollen; alternaria tenuis; cat; dog; 2 species of house dust mite), IgE-associated allergic disease symptoms (eczema, wheeze, or rhinitis) with sensitization at 6 years of life | less sensitisation to one species of house dust mite (13.4% vs. 20.3%; p = 0.049) |

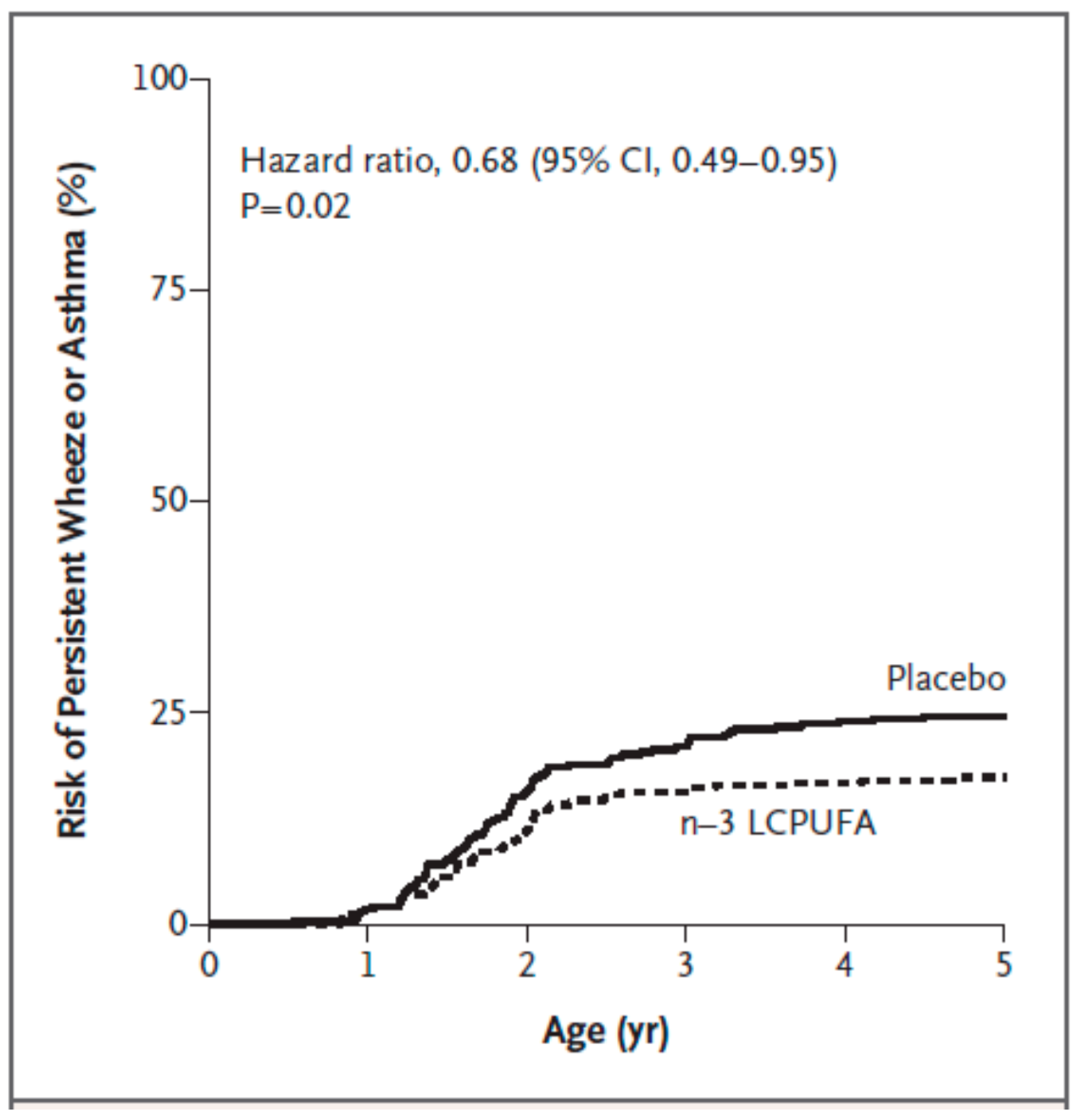

| Bisgaard et al. [70] | pregnant women; n = 736 | fish oil providing 2.4 g n-3 PUFAs daily including 1.32 g EPA and 0.89 g DHA; control group received olive oil; from 24 weeks of gestation until delivery | asthma, allergy, eczema; parental report of lung, skin, lower respiratory tract related symptoms; skin prick test positivity (hens’ egg; cows’ milk; cat; dog) at 6 and 18 months of life | less persistant wheeze/asthma from 3 to 5 years of life (hazard ratio 0.68; p = 0.02) |

| Outcome | Finding (Risk Ratio; 95% Confidence Interval; p) | Studies Included |

|---|---|---|

| atopic eczema (eczema with positive skin prick test) in the first 12 months of life | 0.53; 0.35–0.81; 0.004 | [65,67] |

| any eczema (eczema with or without a positive skin prick test) in the first 12 months of life | 0.85; 0.67–1.07; 0.16 | [65,67] |

| cumulative incidence of IgE-mediated rhino-conjunctivitis (rhino-conjuctivitis with a postive skin prick test) in the first 3 years of life | 0.81; 0.44–1.47; 0.49 | [66,68] |

| positive skin prick test to any allergen in the first 12 months of life | 0.68; 0.52–0.89; 0.006 | [62,65,67] |

| positive skin prick test to hens’ egg in the first 12 months of life | 0.54; 0.39–0.75; 0.0003 | [62,65,67] |

| positive skin prick test to any food extract in the first 12 months of life | 0.58; 0.45–0.75; <0.0001 | [62,65,67] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease? Nutrients 2017, 9, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070784

Miles EA, Calder PC. Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease? Nutrients. 2017; 9(7):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070784

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiles, Elizabeth A., and Philip C. Calder. 2017. "Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease?" Nutrients 9, no. 7: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070784

APA StyleMiles, E. A., & Calder, P. C. (2017). Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease? Nutrients, 9(7), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070784