Adult Nutrient Intakes from Current National Dietary Surveys of European Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying National Diet Surveys (NDS)

2.2. Data Extracted

3. Results

3.1. Data Extracted

3.2. Energy and Nutrient Intakes

3.2.1. Energy

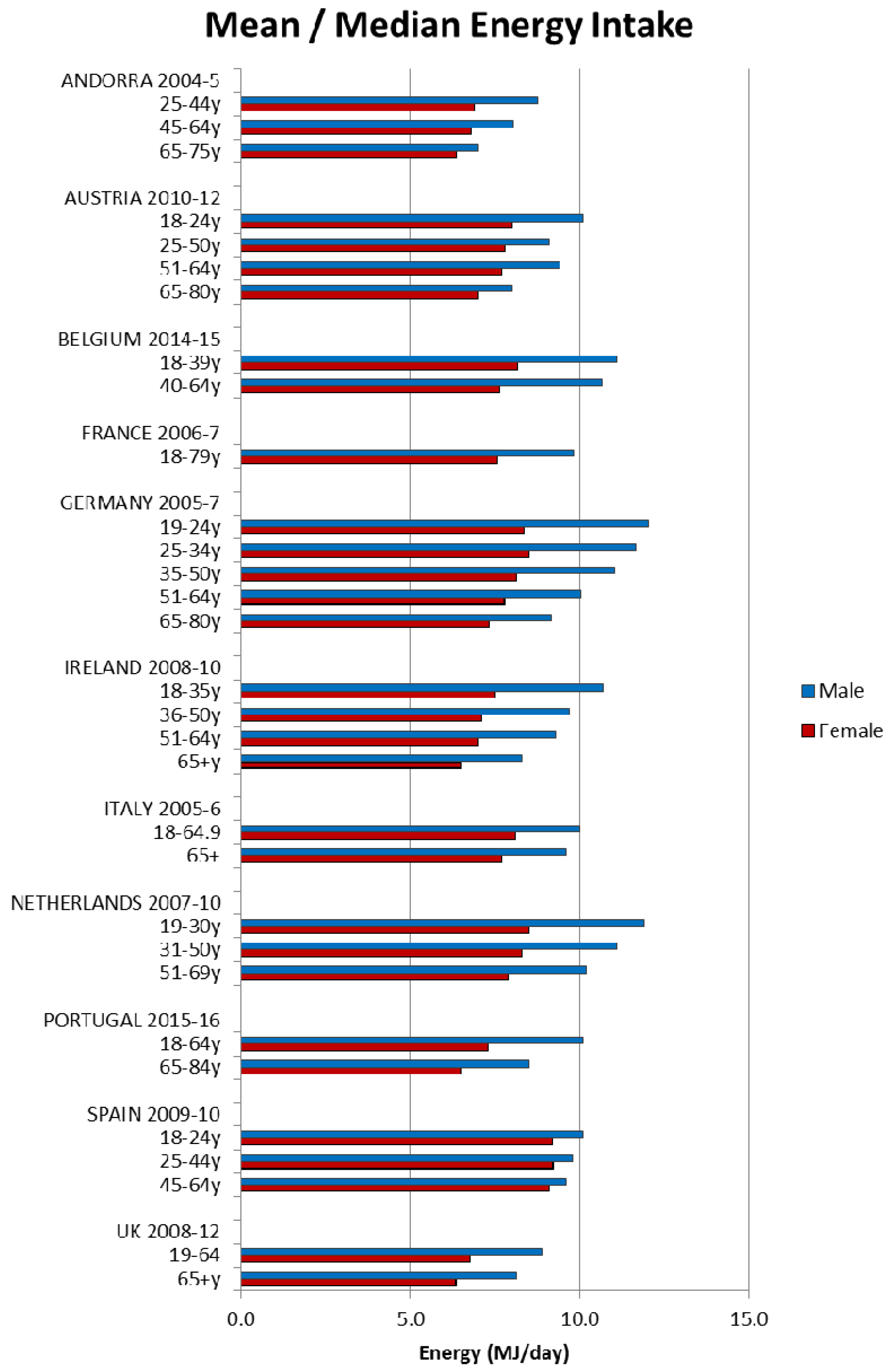

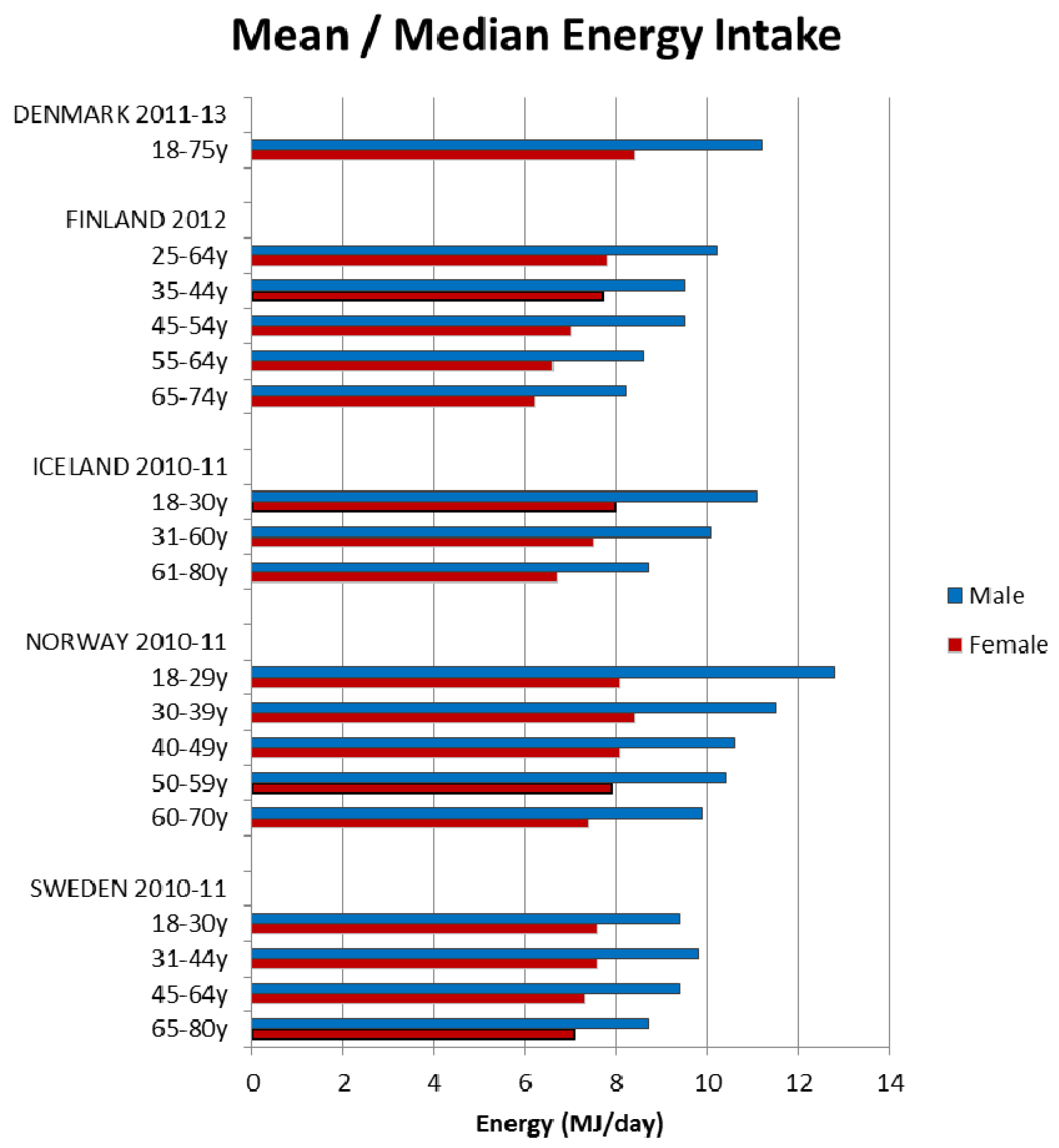

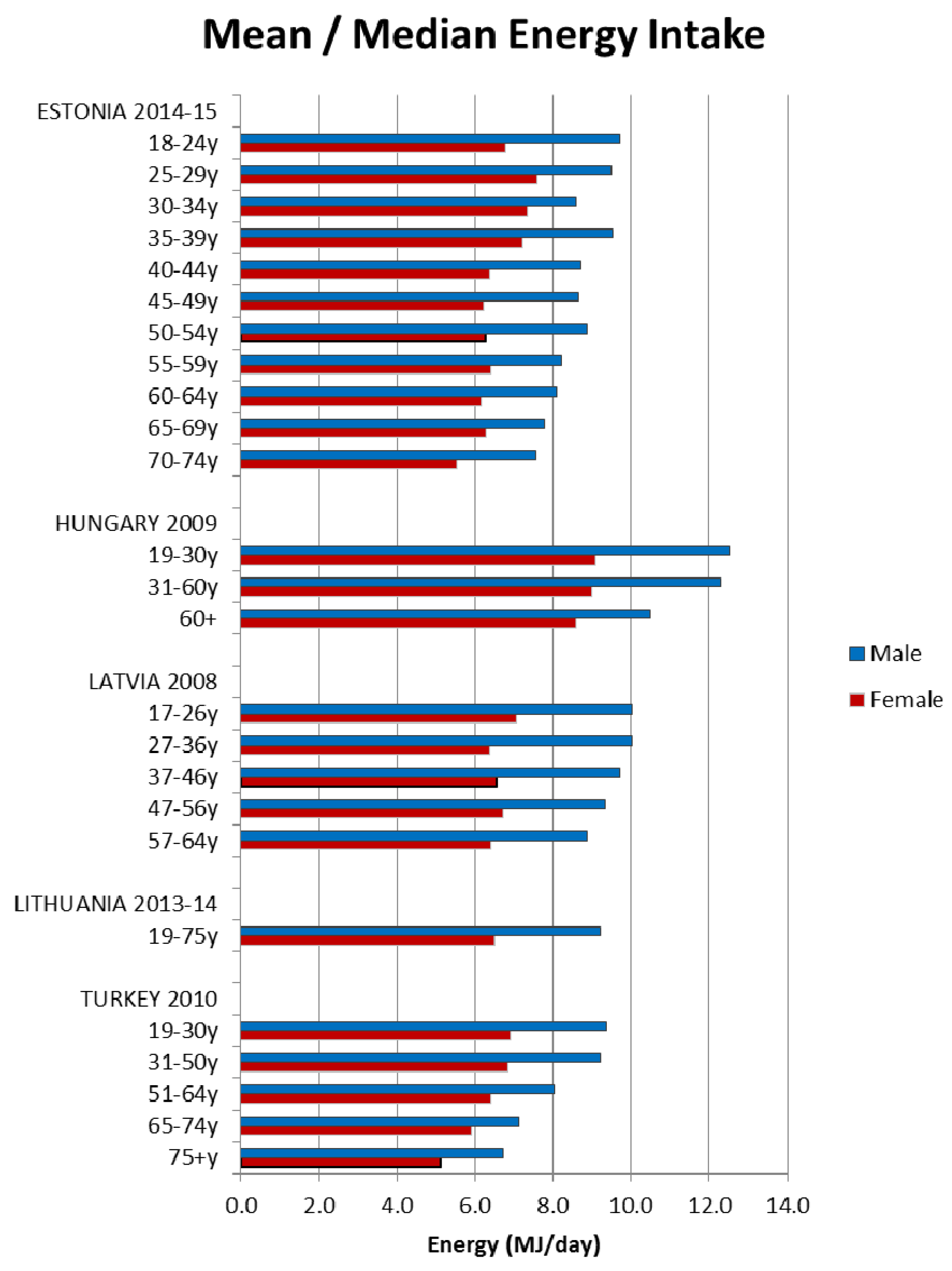

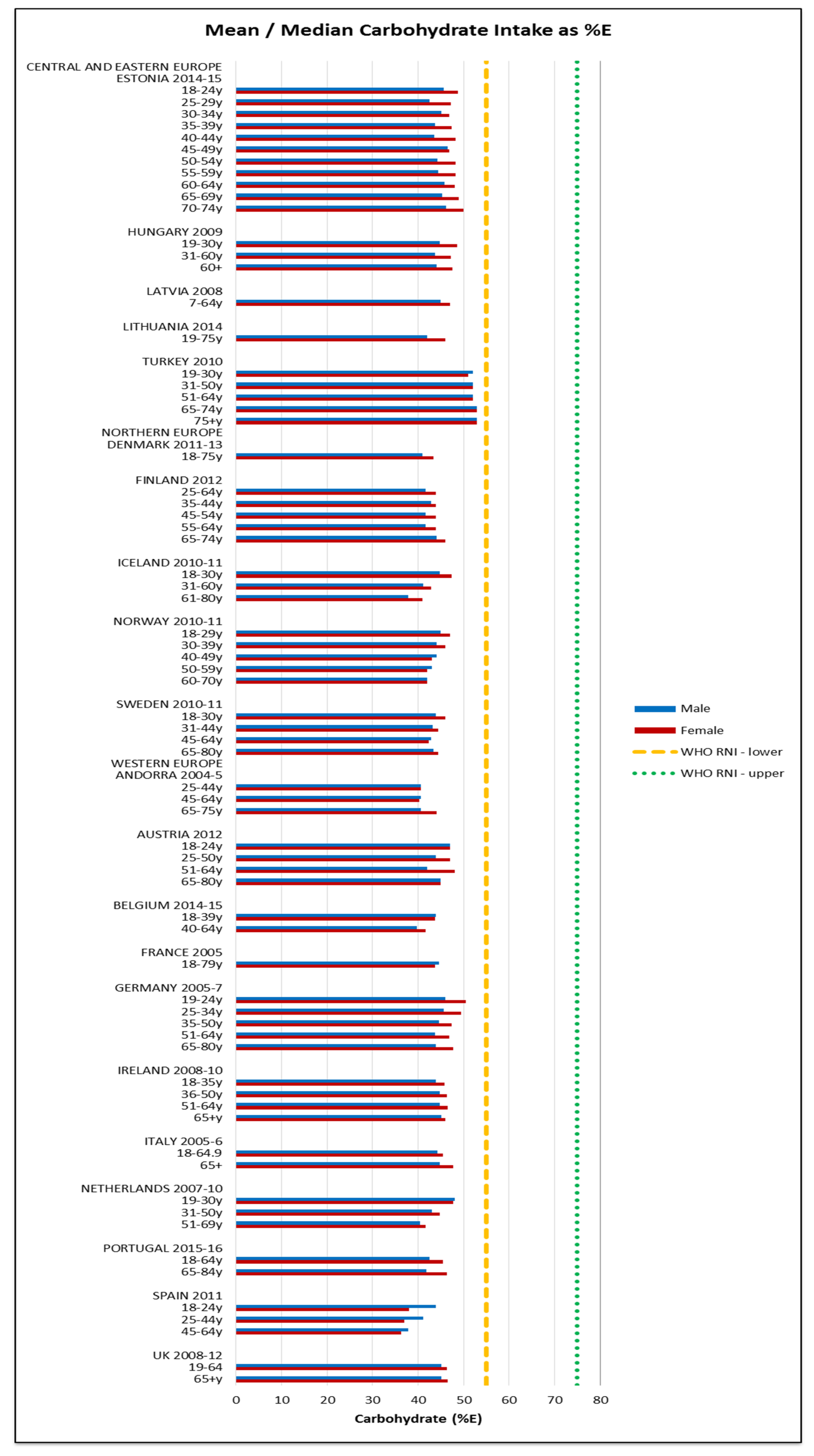

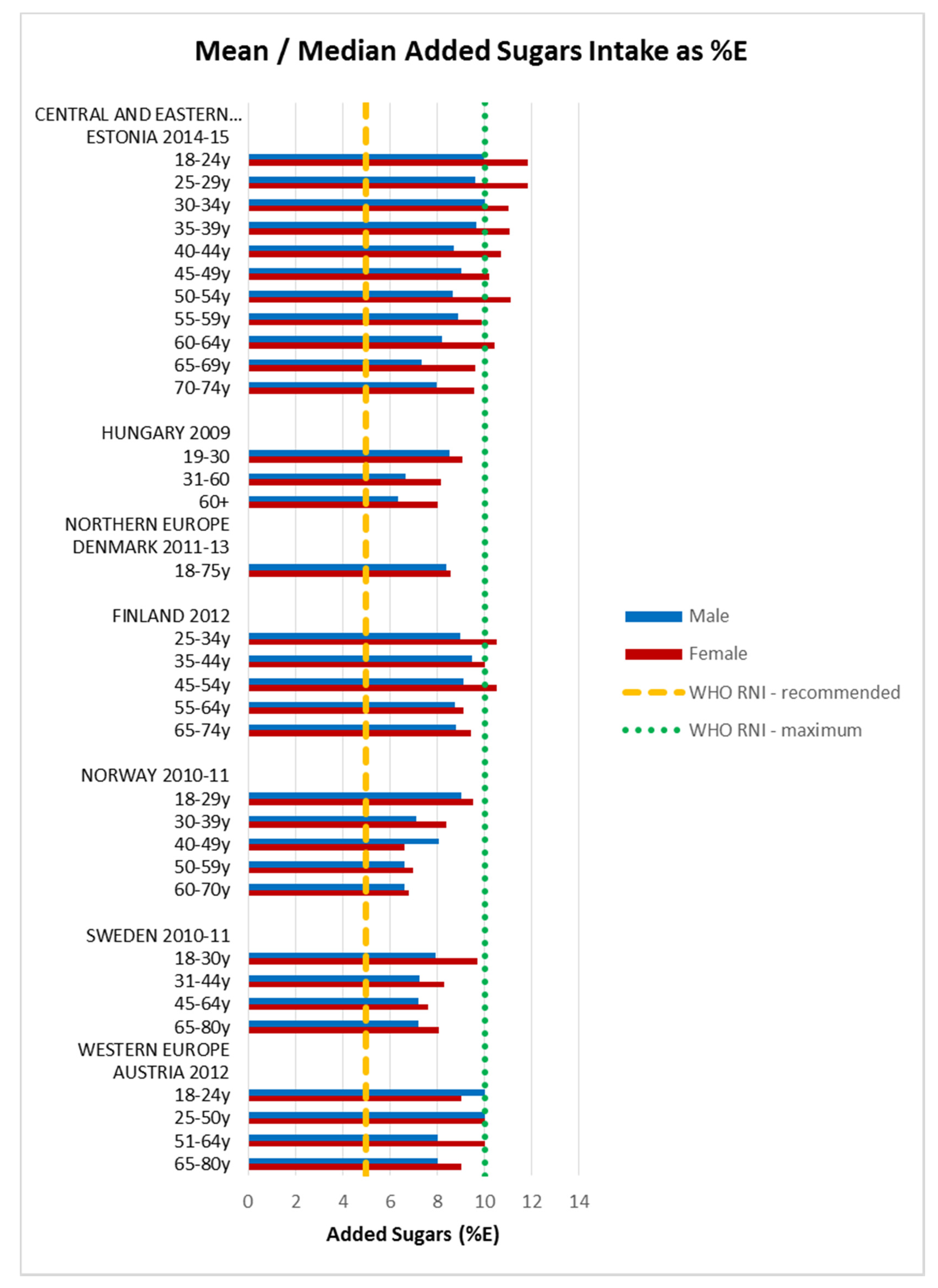

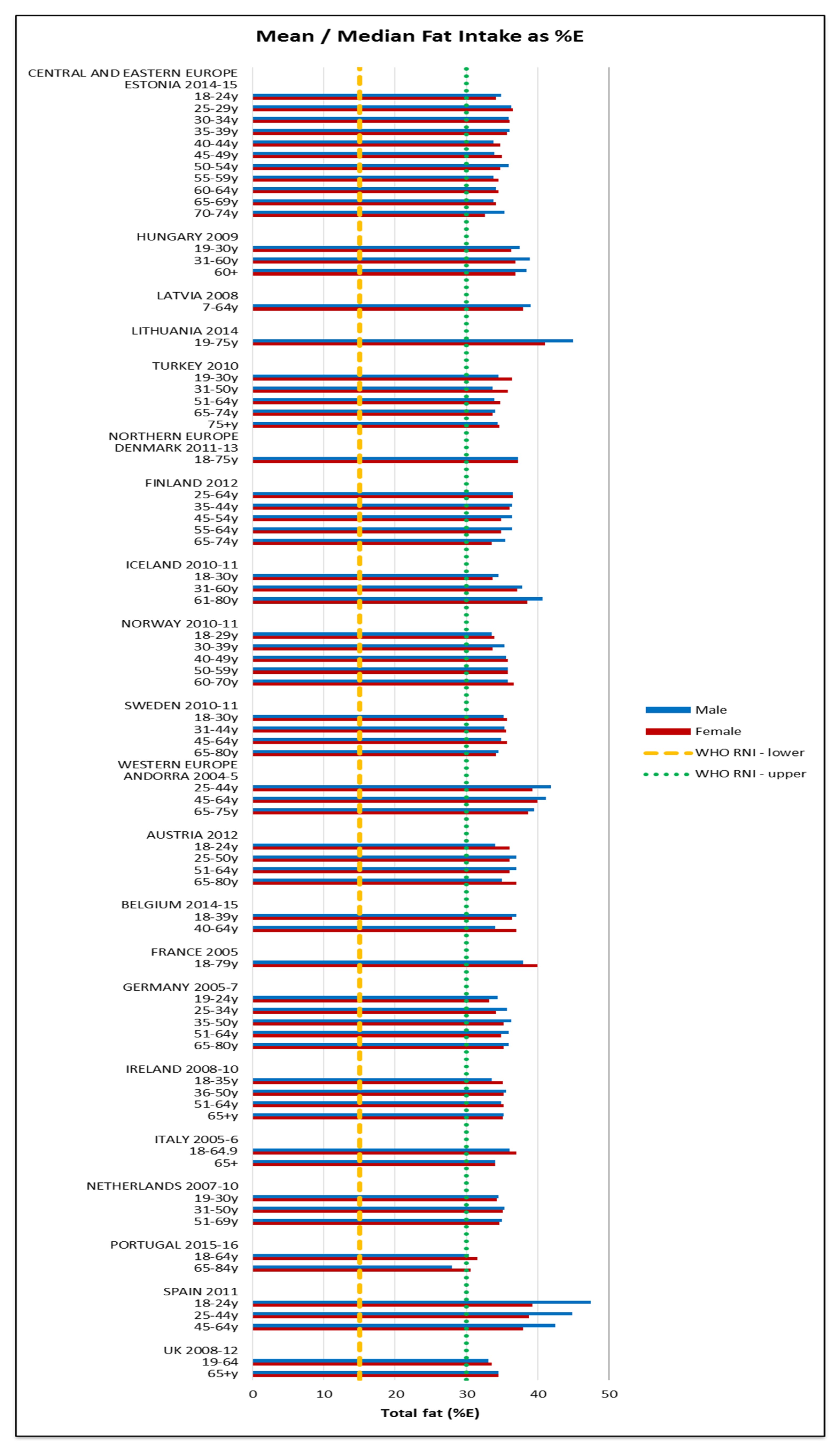

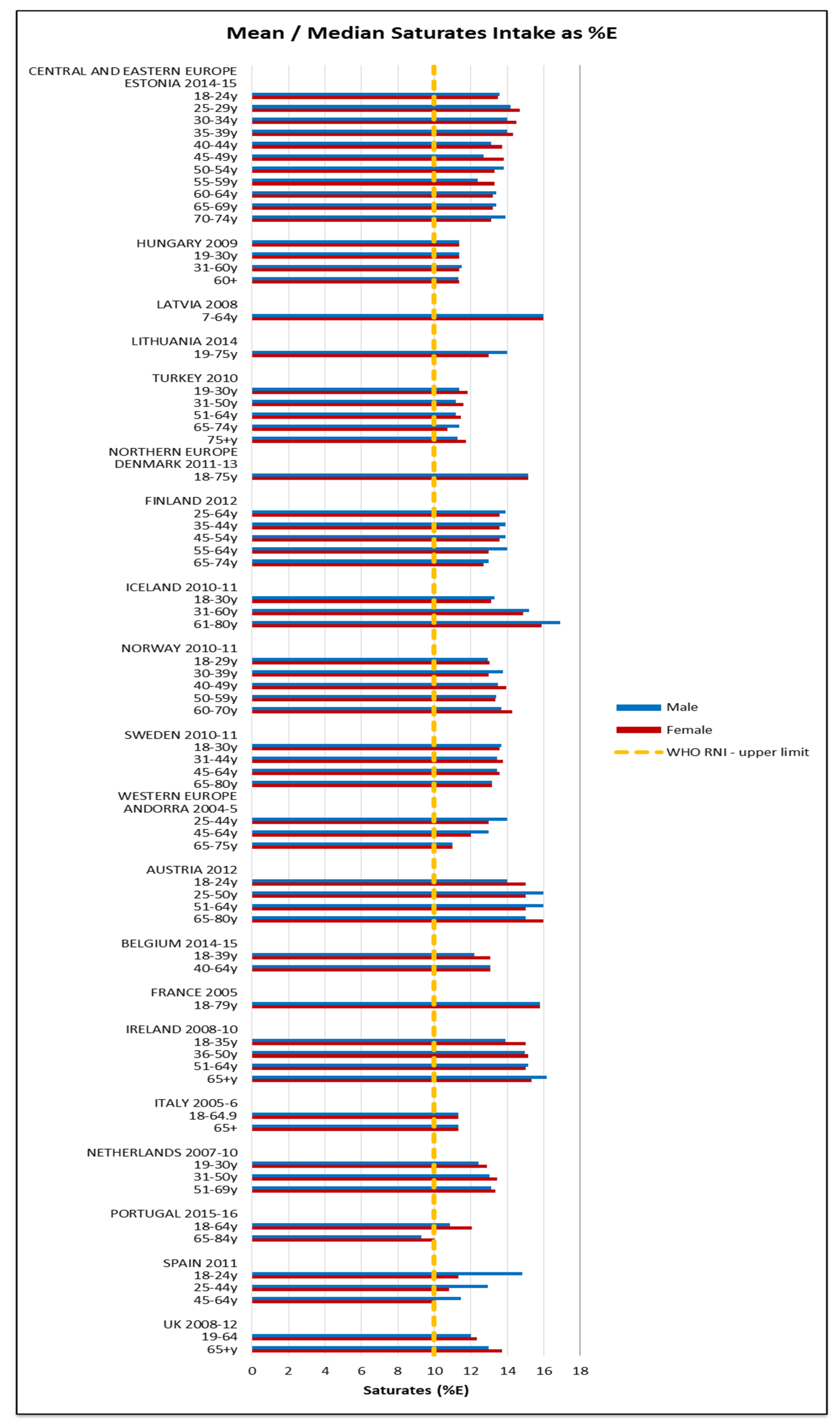

3.2.2. Macronutrients

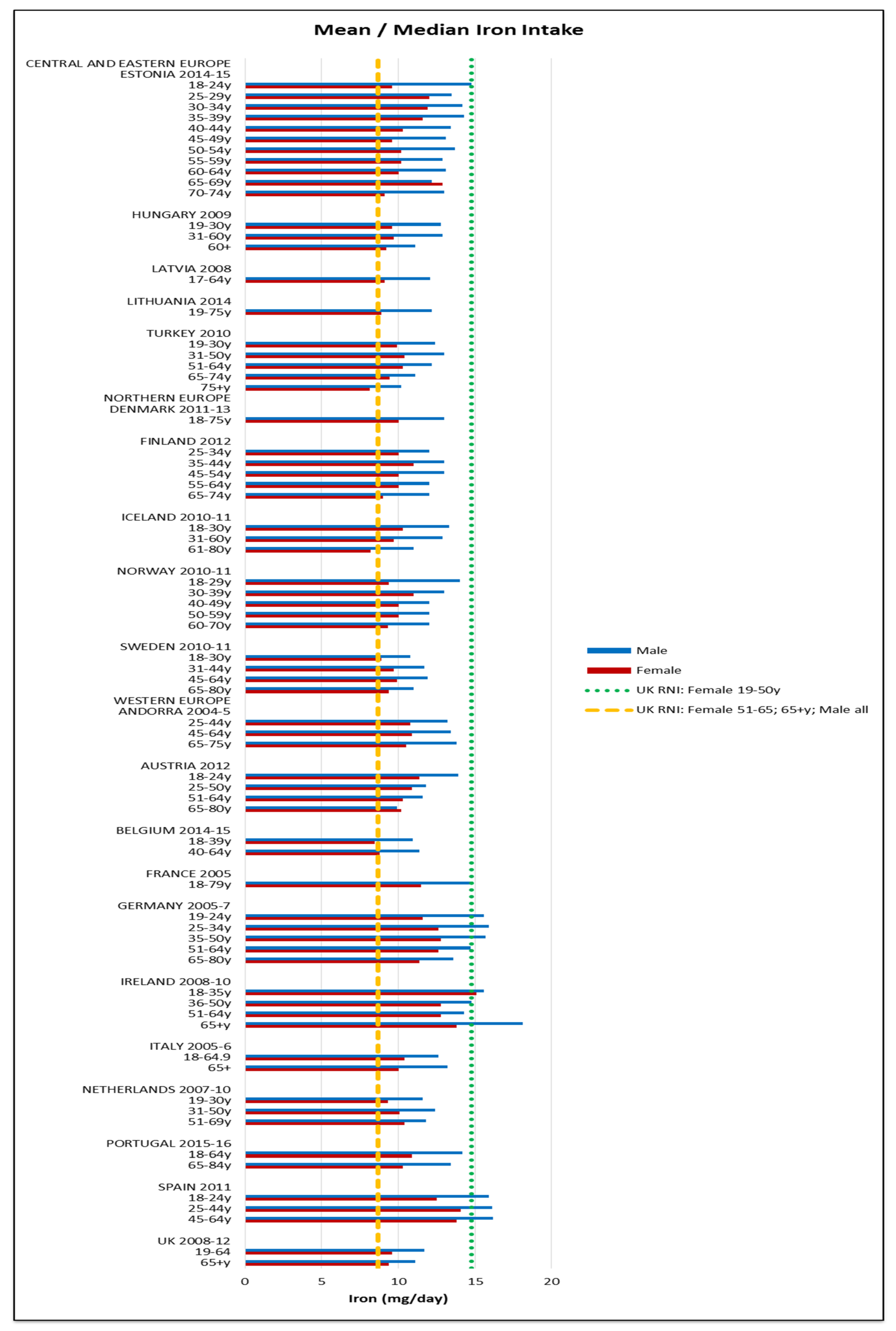

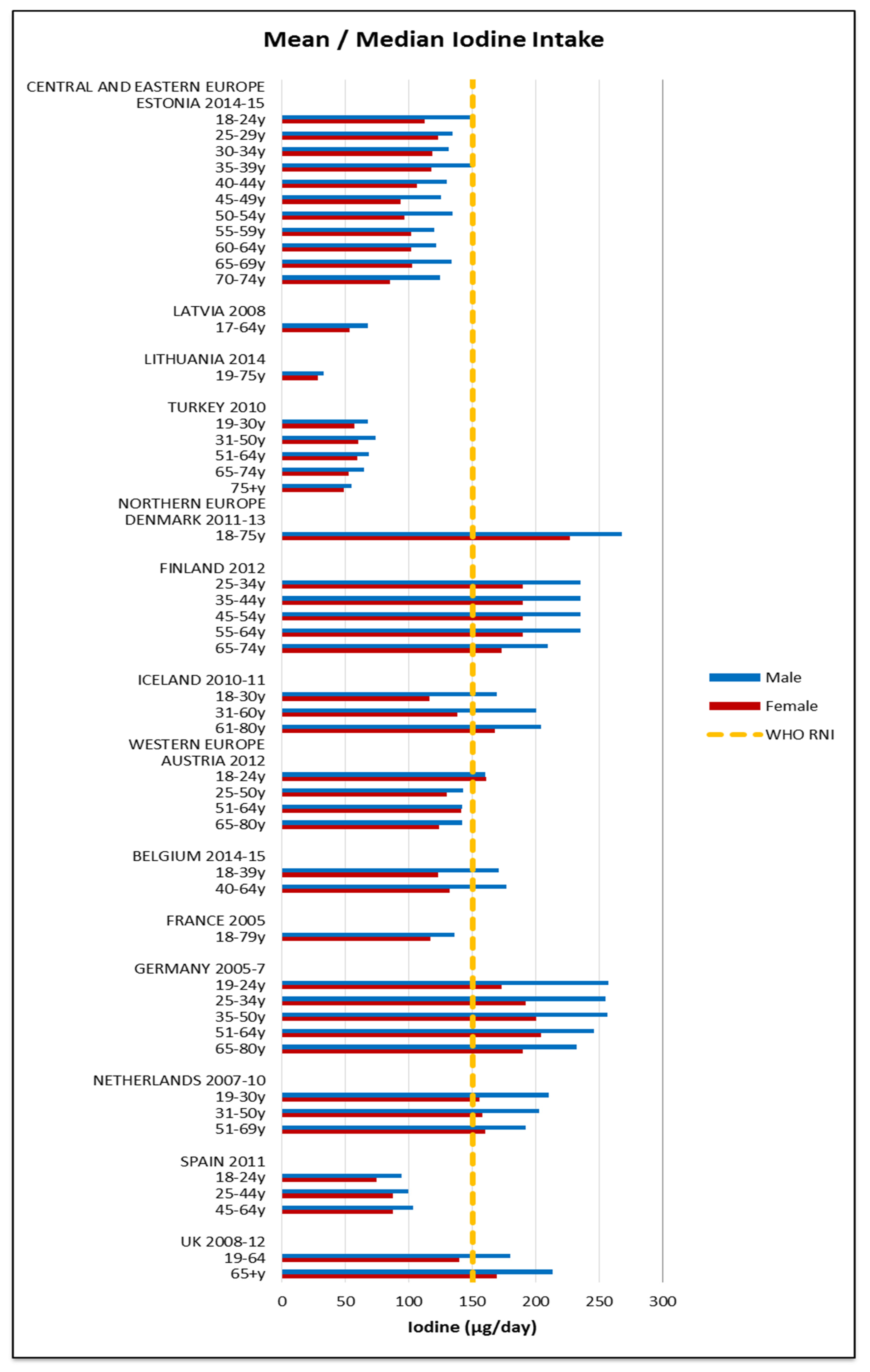

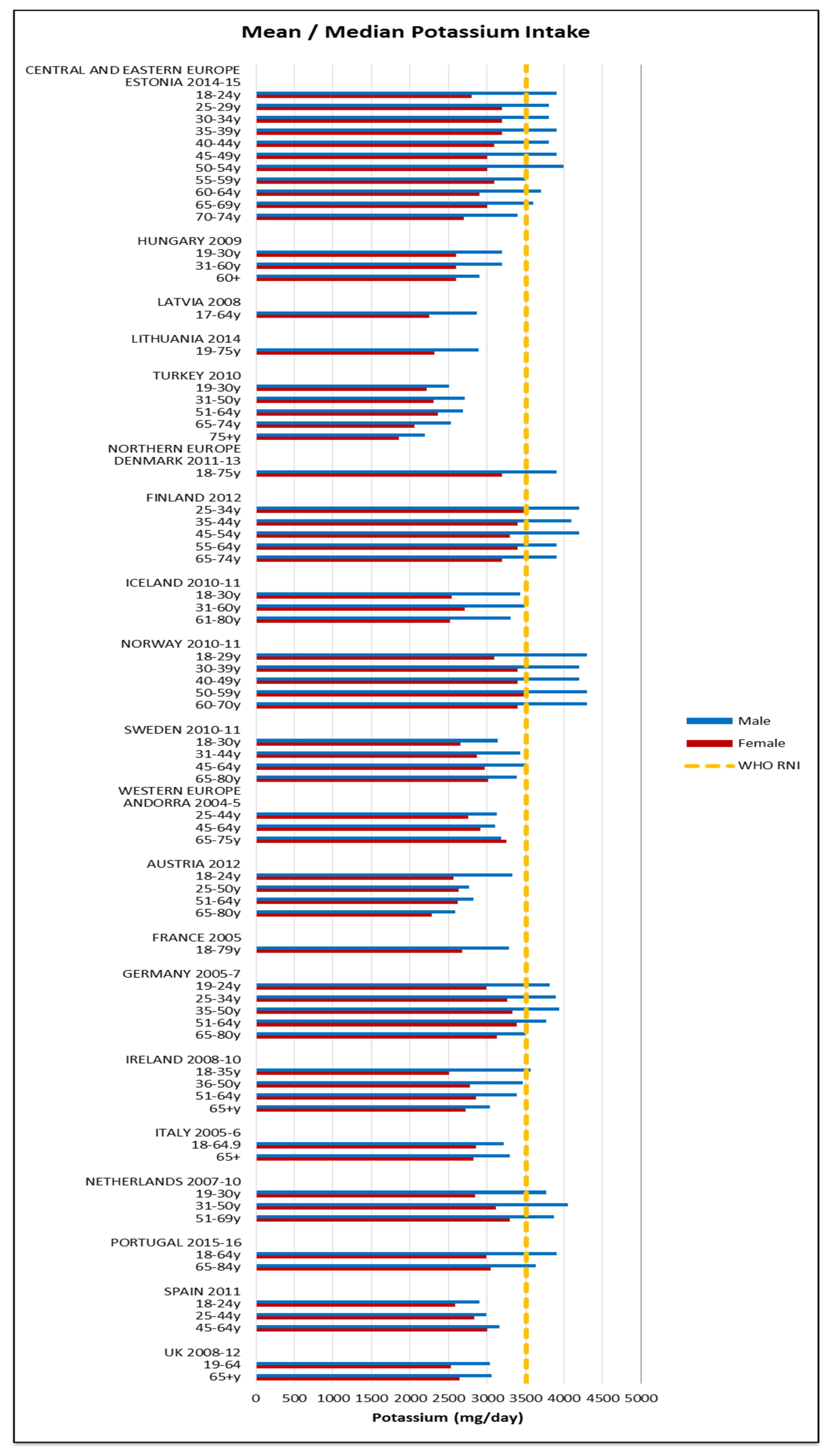

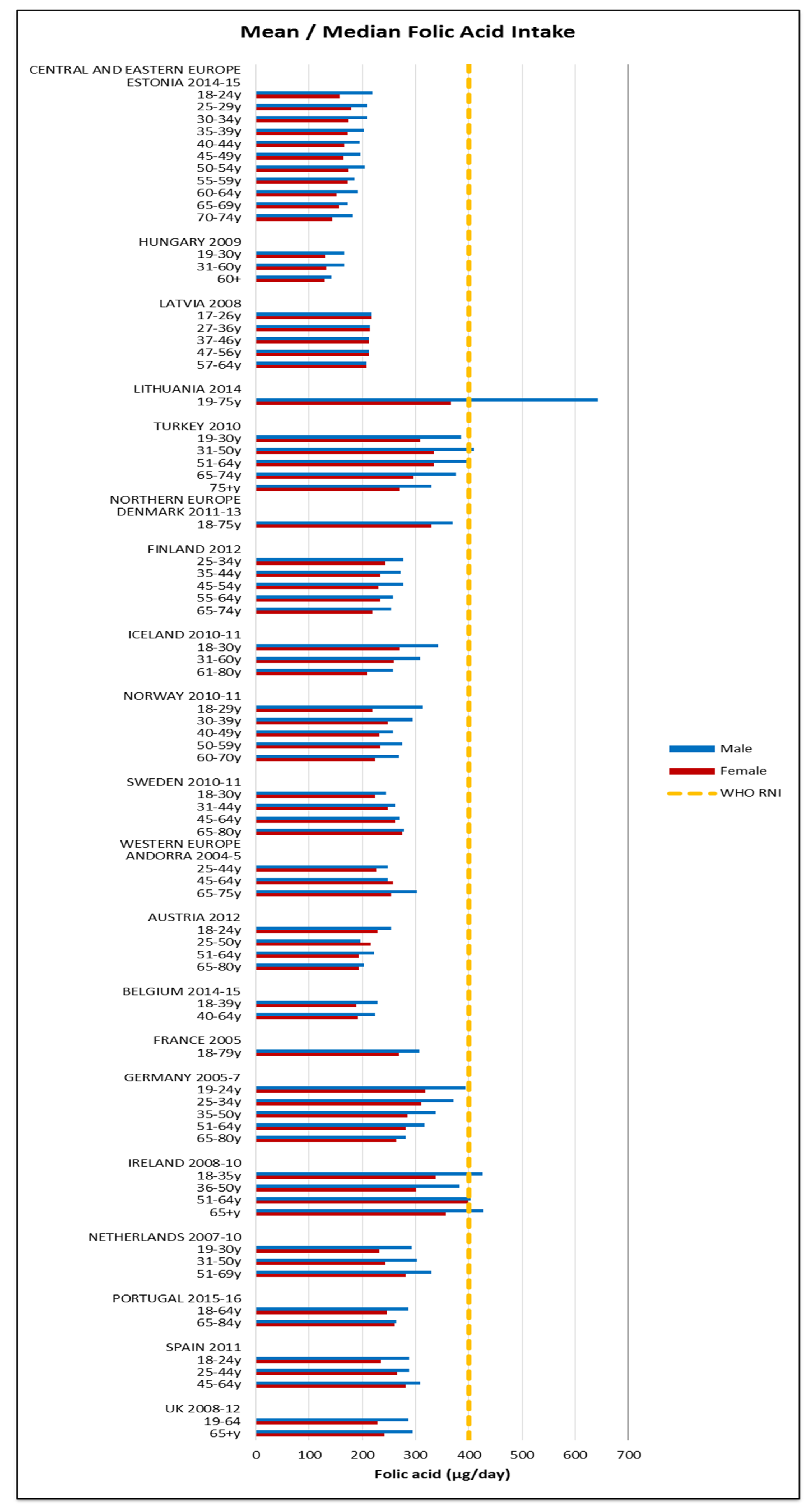

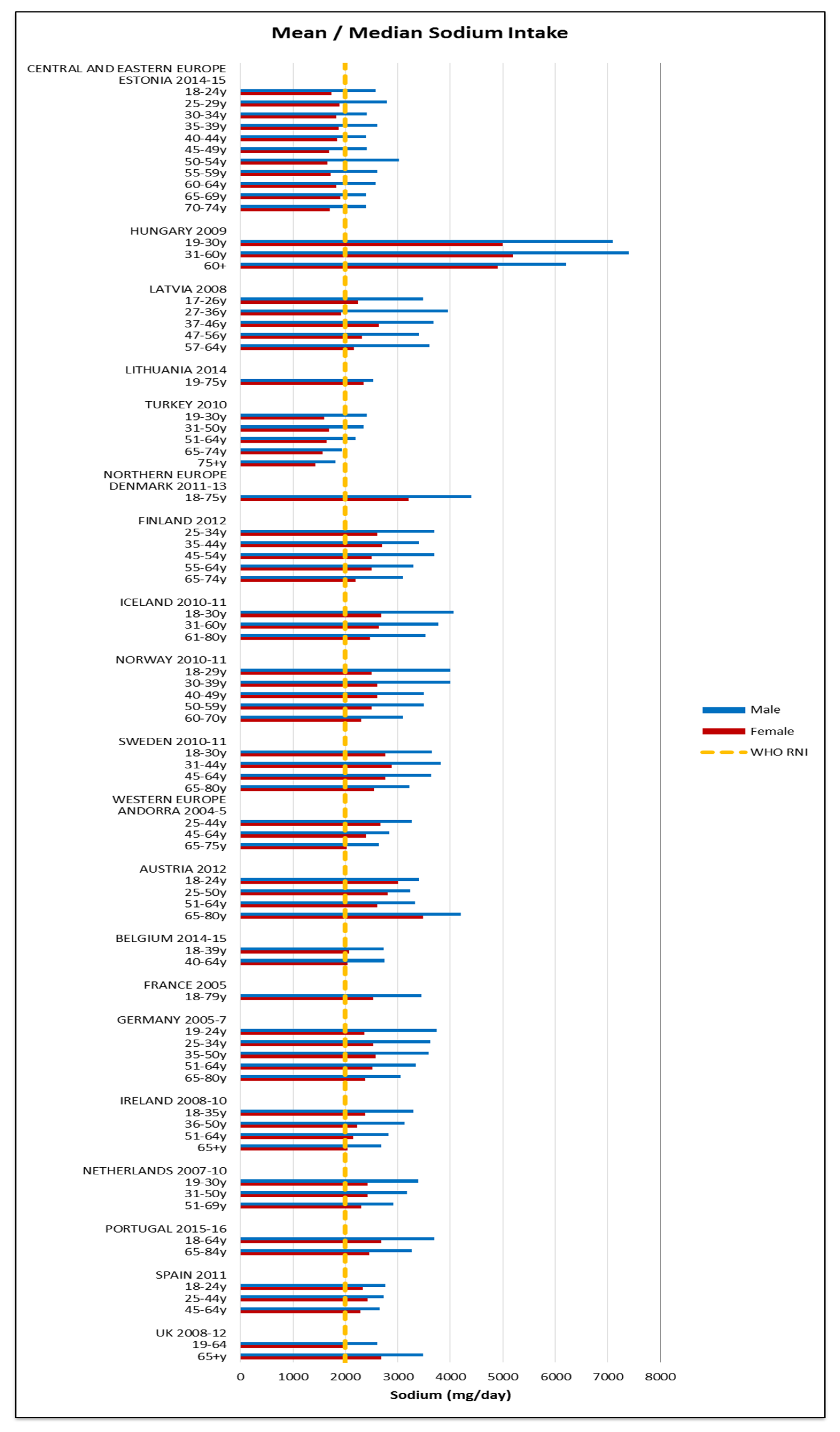

3.2.3. Micronutrients

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Extracted

4.2. Energy Intakes

4.3. Nutrient Intakes and WHO RNI Status

4.4. Carbohydrates and Fats

4.5. Micronutrients

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Mean Macronutrient Intakes across Dietary Surveys

| COUNTRY | SURVEY | YEAR | Energy (MJ) | Energy (Kcal) | Protein (g) | CHO (g) | Sugars (g) | Sucrose (g) | Starch (g) | Fiber (g) | Total Fat (g) | Saturates (g) | MUFA (g) | PUFA (g) | TFAs (g) | n-3 (g) | n-6 (g) |

| Andorra | Evaluation of the nutritional status of the Andorran population | 2004–2005 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 25–44 y | 6.9 | 1650 | 83 | 165 | 75 | 15.8 | 73 | 23.4 | 32.5 | 10.2 | |||||||

| female: 45–64 y | 6.8 | 1628 | 81 | 162 | 77 | 17.6 | 73 | 22.3 | 32.8 | 10.6 | |||||||

| female: 65–75 y | 6.4 | 1518 | 71 | 165 | 83 | 21.3 | 65 | 18.3 | 31.2 | 8.6 | |||||||

| male: 25–44 y | 8.8 | 2093 | 100 | 205 | 88 | 16.8 | 85 | 30.7 | 42.7 | 13.8 | |||||||

| male: 45–64 y | 8.0 | 1919 | 90 | 188 | 84 | 17.1 | 86 | 26.5 | 39.3 | 12.1 | |||||||

| male: 65–75 y | 7.0 | 1679 | 83 | 173 | 80 | 18.3 | 74 | 20.8 | 34.9 | 12.0 | |||||||

| Austria | Austrian nutrition report | 2010–2012 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–24 y | 8.0 | 1917 | 72 | 225 | 43 | 22.0 | 77 | 32.0 | 25.6 | 14.9 | 1.5 | 12.6 | |||||

| female: 25–50 y | 7.8 | 1854 | 70 | 218 | 46 | 22.0 | 74 | 30.9 | 24.7 | 12.4 | 1.5 | 12.2 | |||||

| female: 51–64 y | 7.7 | 1826 | 64 | 219 | 46 | 22.0 | 73 | 30.4 | 22.3 | 14.2 | 1.5 | 12.0 | |||||

| female: 65–80 y | 7.0 | 1675 | 63 | 188 | 38 | 19.0 | 69 | 29.8 | 22.3 | 13.0 | 1.4 | 10.4 | |||||

| male: 18–24 y | 10.1 | 2403 | 90 | 282 | 60 | 24.0 | 91 | 37.4 | 29.4 | 16.0 | 1.6 | 13.9 | |||||

| male: 25–50 y | 9.1 | 2172 | 81 | 239 | 54 | 20.0 | 89 | 38.6 | 29.0 | 14.5 | 1.5 | 12.5 | |||||

| male: 51–64 y | 9.4 | 2245 | 84 | 236 | 45 | 22.0 | 92 | 39.9 | 29.9 | 15.0 | 1.5 | 13.0 | |||||

| male: 65–80 y | 8.0 | 1920 | 67 | 216 | 38 | 20.0 | 75 | 32.0 | 23.5 | 12.8 | 1.4 | 11.1 | |||||

| Belgium | The Belgian food consumption survey 2014–2015 | 2014–2015 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–39 y | 8.2 | 1955 | 71 | 214 | 99 | 116 | 17.3 | 79 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 14.0 | 0.8 | |||||

| female: 40–64 y | 7.6 | 1826 | 71 | 190 | 89 | 100 | 18.8 | 75 | 27.0 | 26.0 | 14.0 | 0.8 | |||||

| male: 18–39 y | 11.1 | 2652 | 95 | 291 | 131 | 155 | 19.3 | 100 | 36.0 | 38.0 | 18.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| male: 40–64 y | 10.7 | 2547 | 96 | 253 | 115 | 137 | 20.1 | 104 | 37.0 | 36.0 | 19.0 | 1.1 | |||||

| Denmark | Danish Dietary habits 2011–2013 | 2011–2013 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–75 y | 8.4 | 2008 | 76 | 211 | 43 | 21.0 | 83 | 33.0 | 31.0 | 13.0 | 1.3 | ||||||

| male: 18–75 y | 11.2 | 2677 | 101 | 269 | 56 | 24.0 | 111 | 45.0 | 41.0 | 17.0 | 1.7 | ||||||

| Estonia | National Dietary Survey | 2014–2015 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–24 y | 6.8 | 1625 | 64 | 200 | 48 | 15.1 | 64 | 25.5 | 22.8 | 10.9 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 8.6 | ||||

| female: 25–29 y | 7.6 | 1818 | 71 | 217 | 54 | 17.1 | 76 | 30.5 | 27.2 | 12.1 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 9.2 | ||||

| female: 30–34 y | 7.3 | 1762 | 71 | 210 | 49 | 18.1 | 73 | 29.6 | 26.4 | 11.6 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 8.9 | ||||

| female: 35–39 y | 7.2 | 1730 | 68 | 205 | 48 | 17.8 | 72 | 29.1 | 26.4 | 11.9 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 9.1 | ||||

| female: 40–44 y | 6.4 | 1529 | 60 | 188 | 41 | 17.3 | 61 | 24.4 | 21.8 | 10.4 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 7.7 | ||||

| female: 45–49 y | 6.2 | 1488 | 59 | 177 | 38 | 16.6 | 60 | 23.6 | 21.9 | 10.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 7.7 | ||||

| female: 50–54 y | 6.3 | 1505 | 60 | 183 | 42 | 17.6 | 61 | 23.3 | 22.3 | 10.8 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 7.8 | ||||

| female: 55–59 y | 6.4 | 1537 | 64 | 185 | 38 | 18.1 | 62 | 24.6 | 22.6 | 10.7 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 8.0 | ||||

| female: 60–64 y | 6.2 | 1474 | 61 | 179 | 39 | 17.0 | 59 | 22.5 | 22 | 10.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 7.6 | ||||

| female: 65–69 y | 6.3 | 1509 | 62 | 186 | 36 | 17.8 | 59 | 23.3 | 21.4 | 10.3 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 7.5 | ||||

| female: 70–74 y | 5.5 | 1330 | 55 | 168 | 32 | 16.6 | 51 | 20.3 | 18.3 | 8.9 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 6.7 | ||||

| male: 18–24 y | 9.7 | 2326 | 102 | 266 | 58 | 18.1 | 92 | 35.8 | 34.4 | 16.4 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 13.2 | ||||

| male: 25–29 y | 9.5 | 2277 | 94 | 239 | 55 | 16.8 | 93 | 36.9 | 35.2 | 14.7 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 11.4 | ||||

| male: 30–34 y | 8.6 | 2058 | 85 | 234 | 52 | 17.7 | 84 | 33 | 31.3 | 14.4 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 11.2 | ||||

| male: 35–39 y | 9.5 | 2279 | 94 | 252 | 55 | 19.7 | 94 | 36.9 | 34.7 | 16.8 | 0.6 | 4.4 | 12.3 | ||||

| male: 40–44 y | 8.7 | 2085 | 89 | 229 | 45 | 19.3 | 81 | 31.8 | 30.9 | 13.4 | 0.6 | 3.0 | 10.0 | ||||

| male: 45–49 y | 8.6 | 2068 | 79 | 242 | 47 | 20.1 | 80 | 29.7 | 31.3 | 14 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 10.5 | ||||

| male: 50–54 y | 8.9 | 2125 | 89 | 233 | 46 | 20.4 | 89 | 33.9 | 33.8 | 14.9 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 11.1 | ||||

| male: 55–59 y | 8.2 | 1965 | 75 | 221 | 44 | 19.2 | 76 | 27.6 | 29 | 14 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 10.5 | ||||

| male: 60–64 y | 8.1 | 1941 | 81 | 226 | 40 | 20.6 | 75 | 29.6 | 28.1 | 12.6 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 9.3 | ||||

| male: 65–69 y | 7.8 | 1865 | 78 | 213 | 34 | 19.5 | 74 | 29.8 | 27.4 | 12.4 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 9.0 | ||||

| male: 70–74 y | 7.6 | 1814 | 75 | 213 | 36 | 19.6 | 73 | 29.1 | 27.5 | 12.7 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 9.4 | ||||

| Finland | The national FINDIET 2012 survey | 2012 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 25–34 y | 7.8 | 1864 | 76 | 199 | 49 | 19.0 | 78 | 31.0 | 27.0 | 13.4 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 9.8 | ||||

| female: 35–44 y | 7.7 | 1840 | 77 | 195 | 46 | 20.0 | 75 | 29.0 | 27.0 | 13.0 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 9.6 | ||||

| female: 45–54 y | 7.0 | 1673 | 68 | 180 | 44 | 21.0 | 67 | 26.0 | 24.0 | 11.6 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 8.4 | ||||

| female: 55–64 y | 6.6 | 1577 | 67 | 171 | 36 | 22.0 | 63 | 24.0 | 22.0 | 11.6 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 8.5 | ||||

| female: 65–74 y | 6.2 | 1482 | 62 | 166 | 35 | 21.0 | 57 | 22.0 | 20.0 | 10.6 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 7.6 | ||||

| male: 25–34 y | 10.2 | 2449 | 106 | 249 | 55 | 19.0 | 102 | 40.0 | 37.0 | 16.9 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 12.5 | ||||

| male: 35–44 y | 9.5 | 2275 | 96 | 237 | 54 | 21.0 | 93 | 36.0 | 34.0 | 15.6 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 11.4 | ||||

| male: 45–54 y | 9.5 | 2282 | 96 | 237 | 52 | 23.0 | 93 | 36.0 | 34.0 | 16.2 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 11.8 | ||||

| male: 55–64 y | 8.6 | 2053 | 85 | 207 | 45 | 23.0 | 86 | 33.0 | 30.0 | 14.9 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 10.8 | ||||

| male: 65–74 y | 8.2 | 1954 | 80 | 212 | 43 | 24.0 | 77 | 29.0 | 28.0 | 13.7 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 9.7 | ||||

| France | INCA2 | 2006–2007 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–79 y | 7.6 | 1809 | 74 | 199 | 89 | 105 | 16.0 | 80 | 32.1 | 28.6 | 12.3 | ||||||

| male: 18–79 y | 9.8 | 2348 | 100 | 262 | 101 | 153 | 19.2 | 100 | 41.2 | 35.7 | 14.5 | ||||||

| Germany | German National Nutrition Survey II | 2005–2007 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 19–24 y | 8.4 | 1996 | 65 | 252 | 21.7 | 74 | |||||||||||

| female: 25–34 y | 8.5 | 2031 | 70 | 251 | 24.0 | 77 | |||||||||||

| female: 35–50 y | 8.2 | 1948 | 69 | 231 | 24.7 | 76 | |||||||||||

| female: 51–64 y | 7.8 | 1856 | 67 | 217 | 26.1 | 72 | |||||||||||

| female: 65–80 y | 7.3 | 1753 | 62 | 209 | 24.9 | 69 | |||||||||||

| male: 19–24 y | 12.0 | 2872 | 102 | 331 | 24.6 | 110 | |||||||||||

| male: 325–34 y | 11.6 | 2783 | 99 | 318 | 25.8 | 110 | |||||||||||

| male: 35–50 y | 11.0 | 2640 | 94 | 294 | 27.3 | 106 | |||||||||||

| male: 51–64 y | 10.0 | 2400 | 86 | 262 | 27.4 | 96 | |||||||||||

| male: 65–80 y | 9.2 | 2191 | 78 | 241 | 27.3 | 88 | |||||||||||

| Hungary | Hungarian Dietary Survey 2009 | 2009 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 19–30 y | 9.1 | 2175 | 81 | 265 | 49 | 20.7 | 88 | 26.2 | 26.8 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 22.1 | |||||

| female: 31–60 y | 9.0 | 2151 | 81 | 254 | 44 | 21.0 | 88 | 25.9 | 27.1 | 22.7 | 0.9 | 22.0 | |||||

| female: 60+ | 8.6 | 2055 | 75 | 245 | 41 | 20.6 | 84 | 25.0 | 26.3 | 21.2 | 0.9 | 20.4 | |||||

| male: 19–30 y | 12.5 | 2988 | 112 | 334 | 64 | 25.5 | 124 | 37.5 | 39.8 | 30.0 | 1.2 | 29.1 | |||||

| male: 31–60 y | 12.3 | 2940 | 109 | 322 | 49 | 25.4 | 127 | 37.6 | 41.4 | 30.4 | 1.2 | 29.5 | |||||

| male: 60+ | 10.5 | 2510 | 92 | 277 | 40 | 23.1 | 107 | 31.7 | 35.1 | 25.5 | 1.0 | 24.6 | |||||

| Iceland | The Diet of Icelanders—a national dietary survey 2010–2011 | 2010–2011 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–30 y | 8.0 | 1895 | 75 | 222 | 108 | 16.2 | 71 | 27.6 | 23.2 | 12.4 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 9.7 | ||||

| female: 31–60 y | 7.5 | 1795 | 76 | 190 | 86 | 16.5 | 74 | 29.7 | 23.4 | 12.5 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 9.4 | ||||

| female: 61–80 y | 6.7 | 1610 | 71 | 161 | 74 | 14.8 | 69 | 28.4 | 21.9 | 10.7 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 7.6 | ||||

| male: 18–30 y | 11.1 | 2635 | 116 | 288 | 129 | 19.1 | 101 | 38.9 | 32.5 | 17.1 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 13.6 | ||||

| male: 31–60 y | 10.1 | 2402 | 107 | 242 | 105 | 17.6 | 101 | 40.5 | 32.3 | 16.2 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 12.3 | ||||

| male: 61–80 y | 8.7 | 2081 | 97 | 192 | 80 | 16.7 | 94 | 39.1 | 30.1 | 13.7 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 9.5 | ||||

| Ireland | National adult nutrition survey | 2008–2010 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–64 y | 7.2 | 1721 | 70 | 200 | 81 | 115 | 17.3 | 68 | 28.9 | 27.4 | 13.9 | 1.1 | 1.6 | ||||

| female: 18–35 y | 7.5 | 1793 | 69 | 206 | 84 | 117 | 15.9 | 70 | 29.9 | 29.4 | 14.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | ||||

| female: 36–50 y | 7.1 | 1697 | 71 | 197 | 77 | 115 | 17.5 | 67 | 28.6 | 26.4 | 13.2 | 1.0 | 1.6 | ||||

| female: 51–64 y | 7.0 | 1673 | 73 | 195 | 83 | 109 | 19.5 | 65 | 27.9 | 25.8 | 13.5 | 1.0 | 1.8 | ||||

| female: 65+ y | 6.5 | 1554 | 69 | 187 | 80 | 103 | 18.4 | 61 | 26.5 | 22.6 | 11.7 | 1.0 | 1.7 | ||||

| male: 18–64 y | 10.1 | 2414 | 100 | 266 | 102 | 160 | 21.1 | 92 | 38.7 | 36.4 | 16.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 | ||||

| male: 18–35 y | 10.7 | 2557 | 105 | 281 | 108 | 167 | 21.3 | 95 | 39.5 | 38.3 | 17.9 | 1.7 | 2.0 | ||||

| male: 36–50 y | 9.7 | 2318 | 99 | 259 | 98 | 157 | 21.0 | 92 | 38.6 | 35.6 | 16.2 | 1.5 | 1.9 | ||||

| male: 51–64 y | 9.3 | 2223 | 93 | 249 | 98 | 148 | 21.0 | 86 | 37.4 | 33.6 | 15.9 | 1.5 | 2.0 | ||||

| male: 65+ y | 8.3 | 1984 | 85 | 226 | 89 | 133 | 19.6 | 78 | 35.6 | 29.8 | 13.1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | ||||

| Italy | The third Italian National food consumption survey INRAN-SCAI | 2005–2006 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–64.9 | 8.1 | 1939 | 76 | 237 | 80 | 142 | 17.7 | 79 | 24.4 | 38.3 | 10.0 | ||||||

| female: 65+ | 7.7 | 1834 | 71 | 234 | 79 | 139 | 18.7 | 70 | 22.2 | 34.1 | 8.0 | ||||||

| male: 18–64.9 | 10.0 | 2390 | 93 | 283 | 86 | 179 | 19.6 | 95 | 29.7 | 45.9 | 12.2 | ||||||

| male: 65+ | 9.6 | 2296 | 88 | 275 | 82 | 174 | 21.6 | 87 | 26.8 | 43.5 | 10.4 | ||||||

| Latvia | Latvian National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2009 | 2007–2009 | |||||||||||||||

| female: ALL | 6.7 | 1613 | 55 | 190 | 15.8 | 68 | 28.1 | 24.0 | 10.8 | ||||||||

| male: ALL | 9.1 | 2171 | 79 | 246 | 20.2 | 93 | 38.1 | 33.4 | 14.8 | ||||||||

| female: 17–26 y | 7.1 | 1690 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 27–36 y | 6.4 | 1523 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 37–46 y | 6.5 | 1562 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 47–56 y | 6.7 | 1608 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 57–64 y | 6.4 | 1530 | |||||||||||||||

| male: 17–26 y | 10.0 | 2394 | |||||||||||||||

| male: 27–36 y | 10.0 | 2393 | |||||||||||||||

| male: 37–46 y | 9.7 | 2319 | |||||||||||||||

| male: 47–56 y | 9.3 | 2230 | |||||||||||||||

| male: 57–64 y | 8.9 | 2121 | |||||||||||||||

| Lithuania | Study and evaluation of actual nutrition and nutrition habits of Lithuanian adult population | 2013–2014 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 19–75 y | 6.5 | 1561 | 56 | 178 | 56 | 14.6 | 71 | 21.9 | 26.8 | 15.5 | |||||||

| male: 19–75 y | 9.2 | 2188 | 75 | 224 | 55 | 17.2 | 108 | 33.5 | 41.1 | 23.8 | |||||||

| all: 19–34 y | 8.1 | 1936 | 65 | 209 | 58 | 15.4 | 92 | 28.4 | 34.8 | 20.1 | |||||||

| all: 35–49 y | 7.8 | 1855 | 66 | 197 | 56 | 16.1 | 90 | 27.7 | 34.0 | 19.7 | |||||||

| all: 50–64 y | 7.4 | 1763 | 63 | 191 | 55 | 15.8 | 83 | 25.9 | 31.7 | 18.3 | |||||||

| all: 65–75 y | 6.7 | 1600 | 57 | 183 | 51 | 15.1 | 72 | 22.3 | 27.3 | 15.8 | |||||||

| The Netherlands | Dutch National Food Consumption Survey (DNFCS) 2007–2010 | 2007–2010 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 19–30 y | 8.5 | 2028 | 73 | 242 | 121 | 18.0 | 77 | 29.0 | 26.9 | 14.8 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 12.3 | ||||

| female: 31–50 y | 8.3 | 1983 | 75 | 222 | 104 | 18.9 | 77 | 29.6 | 26.6 | 14.6 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 11.9 | ||||

| female: 51–69 y | 7.9 | 1874 | 77 | 195 | 92 | 18.8 | 72 | 27.8 | 24.0 | 13.8 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 11.3 | ||||

| male: 19–30 y | 11.9 | 2847 | 98 | 342 | 152 | 22.4 | 109 | 39.3 | 39.1 | 21.7 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 18.1 | ||||

| male: 31–50 y | 11.1 | 2651 | 97 | 285 | 126 | 23.7 | 104 | 38.3 | 36.2 | 21.0 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 17.4 | ||||

| male: 51–69 y | 10.2 | 2425 | 97 | 246 | 107 | 21.6 | 94 | 35.4 | 32.2 | 18.6 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 15.4 | ||||

| Norway | Norkost3 | 2010–2011 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–70 y | 8.0 | 1912 | 81 | 205 | 36 | 22.0 | 75 | 29.0 | 25.0 | 13.0 | |||||||

| male: 18–70 y | 10.9 | 2605 | 112 | 278 | 48 | 26.0 | 102 | 39.0 | 34.0 | 18.0 | |||||||

| female: 18–29 y | 8.1 | 1936 | 80 | 221 | 46 | 21.0 | 73 | 28.0 | 25.0 | 13.0 | |||||||

| female: 30–39 y | 8.4 | 2008 | 83 | 232 | 42 | 24.0 | 75 | 29.0 | 25.0 | 14.0 | |||||||

| female: 40–49 y | 8.1 | 1936 | 83 | 202 | 32 | 22.0 | 77 | 30.0 | 26.0 | 14.0 | |||||||

| female: 50–59 y | 7.9 | 1888 | 81 | 194 | 33 | 22.0 | 75 | 28.0 | 26.0 | 14.0 | |||||||

| female: 60–70 y | 7.4 | 1769 | 77 | 182 | 30 | 22.0 | 72 | 28.0 | 24.0 | 13.0 | |||||||

| male: 18–29 y | 12.8 | 3059 | 130 | 339 | 69 | 29.0 | 114 | 44.0 | 38.0 | 21.0 | |||||||

| male: 30–39 y | 11.5 | 2749 | 118 | 298 | 49 | 26.0 | 108 | 42.0 | 37.0 | 19.0 | |||||||

| male: 40–49 y | 10.6 | 2533 | 107 | 275 | 51 | 25.0 | 100 | 38.0 | 34.0 | 19.0 | |||||||

| male: 50–59 y | 10.4 | 2486 | 109 | 259 | 41 | 26.0 | 99 | 37.0 | 33.0 | 18.0 | |||||||

| male: 60–70 y | 9.9 | 2366 | 102 | 247 | 39 | 27.0 | 94 | 36.0 | 31.0 | 17.0 | |||||||

| Portugal | National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF) | 2015–2016 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–64 y | 7.3 | 1747 | 80 | 199 | 78 | 16.9 | 61 | 23.4 | 25.2 | 11.1 | 0.9 | 9.9 | |||||

| female: 65–84 y | 6.5 | 1555 | 70 | 180 | 73 | 18.1 | 53 | 17.3 | 21.7 | 9.1 | 0.6 | 7.9 | |||||

| male: 18–64 y | 10.1 | 2398 | 111 | 255 | 89 | 19.9 | 81 | 28.9 | 33.9 | 13.7 | 1.1 | 13.1 | |||||

| male: 65–84 y | 8.5 | 2030 | 91 | 212 | 71 | 20.6 | 63 | 20.9 | 26.4 | 10.8 | 0.7 | 9.6 | |||||

| Spain | ENIDE 2011 | 2009–2010 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–24 y | 9.2 | 2186 | 88 | 209 | 17.1 | 95 | 27.5 | 40.1 | 13.0 | ||||||||

| female: 25–44 y | 9.2 | 2187 | 88 | 202 | 18.9 | 94 | 26.2 | 38.9 | 12.4 | ||||||||

| female: 45–64 y | 9.1 | 2162 | 88 | 193 | 19.7 | 91 | 24.2 | 38.1 | 12.6 | ||||||||

| male: 18–24 y | 10.1 | 2402 | 117 | 275 | 20.5 | 127 | 39.6 | 53.3 | 17.1 | ||||||||

| male: 25–44 y | 9.8 | 2340 | 109 | 248 | 20.4 | 117 | 33.6 | 49.1 | 15.7 | ||||||||

| male: 45–64 y | 9.6 | 2281 | 106 | 222 | 21.7 | 108 | 29.0 | 45.1 | 14.5 | ||||||||

| Sweden | Riksmaten 2010–11 Swedish Adult Dietary Survey | 2010–2011 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 18–30 y | 7.6 | 1819 | 69 | 205 | 44 | 17.3 | 72 | 27.4 | 27.1 | 12.0 | 2.4 | 9.2 | |||||

| female: 31–44 y | 7.6 | 1820 | 73 | 199 | 38 | 18.5 | 72 | 27.8 | 26.9 | 11.6 | 2.4 | 8.7 | |||||

| female: 45–64 y | 7.3 | 1755 | 73 | 182 | 34 | 19.3 | 70 | 26.5 | 26.0 | 11.7 | 2.5 | 8.7 | |||||

| female: 65–80 y | 7.1 | 1703 | 70 | 186 | 34 | 20.0 | 65 | 24.9 | 23.9 | 10.6 | 2.6 | 7.6 | |||||

| male: 18–30 y | 9.4 | 2246 | 95 | 241 | 45 | 18.6 | 88 | 34.1 | 32.8 | 14.0 | 2.7 | 10.6 | |||||

| male: 31–44 y | 9.8 | 2343 | 95 | 250 | 43 | 21.3 | 92 | 35.0 | 34.9 | 14.9 | 2.9 | 11.4 | |||||

| male: 45–64 y | 9.4 | 2254 | 93 | 237 | 41 | 21.8 | 87 | 33.7 | 32.8 | 13.9 | 2.9 | 10.3 | |||||

| male: 65–80 y | 8.7 | 2083 | 84 | 223 | 38 | 22.5 | 80 | 30.5 | 29.6 | 13.4 | 3.1 | 9.7 | |||||

| Turkey | Turkey nutrition and health survey 2010 (TNHS) | 2010 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 19–30 y | 6.9 | 1649 | 52 | 204 | 19.0 | 67 | 21.7 | 23.1 | 17.4 | 1.2 | 16.1 | ||||||

| female: 31–50 y | 6.9 | 1638 | 52 | 205 | 20.3 | 65 | 21.1 | 22.4 | 17.3 | 1.2 | 16.0 | ||||||

| female: 51–64 y | 6.4 | 1533 | 49 | 195 | 21.0 | 59 | 19.5 | 21.5 | 14.2 | 1.1 | 13.1 | ||||||

| female: 65–74 y | 5.9 | 1409 | 46 | 183 | 19.3 | 53 | 16.8 | 19.0 | 13.4 | 0.9 | 12.4 | ||||||

| female: 75+ y | 5.1 | 1223 | 39 | 156 | 16.5 | 47 | 16.0 | 17.2 | 10.7 | 0.8 | 9.8 | ||||||

| male: 19–30 y | 9.4 | 2242 | 71 | 282 | 22.4 | 86 | 28.3 | 30.0 | 21.9 | 1.6 | 20.2 | ||||||

| male: 31–50 y | 9.2 | 2203 | 73 | 278 | 23.7 | 83 | 27.4 | 29.3 | 20.4 | 1.5 | 18.8 | ||||||

| male: 51–64 y | 8.0 | 1919 | 64 | 242 | 24.0 | 72 | 23.8 | 26.5 | 17.1 | 1.3 | 15.7 | ||||||

| male: 65–74 y | 7.1 | 1705 | 56 | 220 | 22.9 | 64 | 21.5 | 23.4 | 15.0 | 1.1 | 13.7 | ||||||

| male: 75+ y | 6.7 | 1606 | 52 | 207 | 21.4 | 61 | 20.1 | 24.0 | 13.0 | 1.1 | 11.9 | ||||||

| UK | National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) Years 1–4 | 2008–2012 | |||||||||||||||

| female: 19–64 | 6.8 | 1613 | 65 | 197 | 85 | 113 | 12.8 | 60 | 22.1 | 21.7 | 10.6 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 8.8 | |||

| female: 65+ y | 6.4 | 1510 | 64 | 187 | 88 | 98 | 13.1 | 58 | 23.0 | 19.6 | 9.5 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 7.7 | |||

| male: 19–64 | 8.9 | 2111 | 85 | 251 | 106 | 146 | 14.7 | 78 | 28.4 | 28.5 | 13.4 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 11.2 | |||

| male: 65+ y | 8.1 | 1935 | 78 | 231 | 102 | 129 | 14.9 | 74 | 28.7 | 25.8 | 12.4 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 10.1 | |||

| all: 19–64 | 7.8 | 1861 | 75 | 224 | 95 | 129 | 13.7 | 69 | 25.2 | 25.1 | 12.0 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 10.0 | |||

| all: 65+ y | 7.1 | 1697 | 70 | 206 | 95 | 112 | 13.9 | 65 | 25.5 | 22.3 | 10.7 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 8.7 |

Appendix B. Mean Micronutrient Intakes across Dietary Surveys

| COUNTRY | SURVEY | YEAR | Folic Acid (μg) | Vitamin B12 (μg) | Vitamin D (μg) | Calcium (mg) | Potassium (mg) | Sodium (mg) | Iron (mg) | Iodine (μg) | Zinc (mg) |

| Andorra | Evaluation of the nutritional status of the Andorran population | 2004–2005 | |||||||||

| female: 25–44 y | 227 | 5.3 | 3.4 | 793 | 2751 | 2662 | 10.8 | 8.4 | |||

| female: 45–64 y | 258 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 772 | 2912 | 2401 | 10.9 | 7.9 | |||

| female: 65–75 y | 254 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 834 | 3252 | 2030 | 10.5 | 7.4 | |||

| male: 25–44 y | 248 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 863 | 3124 | 3272 | 13.2 | 10.4 | |||

| male: 45–64 y | 248 | 8.1 | 2.9 | 797 | 3102 | 2835 | 13.4 | 9.7 | |||

| male: 65–75 y | 302 | 7.4 | 1.5 | 737 | 3179 | 2644 | 13.8 | 7.8 | |||

| Austria | Austrian nutrition report | 2010–2012 | |||||||||

| female: 18–24 y | 229 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 956 | 2562 | 3000 | 11.4 | 161 | 10.4 | ||

| female: 25–50 y | 216 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 838 | 2632 | 2800 | 10.9 | 130 | 9.7 | ||

| female: 51–64 y | 193 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 786 | 2623 | 2600 | 10.3 | 141 | 9.1 | ||

| female: 65–80 y | 194 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 632 | 2288 | 3480 | 10.2 | 124 | 8.6 | ||

| male: 18–24 y | 255 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 991 | 3329 | 3400 | 13.9 | 160 | 12.4 | ||

| male: 25–50 y | 197 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 881 | 2768 | 3240 | 11.8 | 143 | 11.4 | ||

| male: 51–64 y | 222 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 802 | 2820 | 3320 | 11.6 | 142 | 11.9 | ||

| male: 65–80 y | 203 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 692 | 2593 | 4200 | 9.9 | 142 | 9.2 | ||

| Belgium | The Belgian food consumption survey 2014–2015 | 2014–2015 | |||||||||

| female: 18–39 y | 189 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 704 | 2076 | 8.5 | 123 | ||||

| female: 40–64 y | 191 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 737 | 2047 | 8.8 | 132 | ||||

| male: 18–39 y | 228 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 842 | 2731 | 11.0 | 171 | ||||

| male: 40–64 y | 224 | 5.5 | 4.6 | 795 | 2748 | 11.4 | 177 | ||||

| Denmark | Danish Dietary habits 2011–2013 | 2011–2013 | |||||||||

| female: 18–75 y | 329 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 1038 | 3200 | 3200 | 10.0 | 227 | 10.5 | ||

| male: 18–75 y | 370 | 8.0 | 5.3 | 1188 | 3900 | 4400 | 13.0 | 268 | 14.1 | ||

| Estonia | National Dietary Survey | 2014–2015 | |||||||||

| female: 18–24 y | 159 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 671 | 2800 | 1737 | 9.6 | 112 | 7.8 | ||

| female: 25–29 y | 178 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 729 | 3200 | 1890 | 12.0 | 123 | 9.2 | ||

| female: 30–34 y | 174 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 730 | 3200 | 1820 | 11.9 | 119 | 9.3 | ||

| female: 35–39 y | 172 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 715 | 3200 | 1878 | 11.6 | 117 | 9.0 | ||

| female: 40–44 y | 167 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 620 | 3100 | 1847 | 10.3 | 107 | 8.0 | ||

| female: 45–49 y | 164 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 595 | 3000 | 1687 | 9.6 | 93 | 7.7 | ||

| female: 50–54 y | 175 | 7.4 | 5.3 | 591 | 3000 | 1657 | 10.2 | 96 | 7.9 | ||

| female: 55–59 y | 173 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 614 | 3100 | 1718 | 10.2 | 102 | 8.4 | ||

| female: 60–64 y | 152 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 566 | 2900 | 1827 | 10.0 | 102 | 8.0 | ||

| female: 65–69 y | 156 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 601 | 3000 | 1909 | 12.9 | 102 | 8.3 | ||

| female: 70–74 y | 143 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 545 | 2700 | 1700 | 9.1 | 85 | 7.4 | ||

| male: 18–24 y | 219 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 950 | 3900 | 2571 | 14.8 | 149 | 12.1 | ||

| male: 25–29 y | 210 | 7.6 | 5.0 | 833 | 3800 | 2798 | 13.5 | 134 | 11.7 | ||

| male: 30–34 y | 209 | 9.1 | 4.0 | 788 | 3800 | 2412 | 14.2 | 132 | 11.1 | ||

| male: 35–39 y | 203 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 894 | 3900 | 2608 | 14.3 | 151 | 12.4 | ||

| male: 40–44 y | 194 | 7.5 | 5.6 | 729 | 3800 | 2396 | 13.4 | 130 | 11.5 | ||

| male: 45–49 y | 196 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 685 | 3900 | 2416 | 13.1 | 125 | 11.2 | ||

| male: 50–54 y | 205 | 10.9 | 6.4 | 777 | 4000 | 3014 | 13.7 | 135 | 12.0 | ||

| male: 55–59 y | 186 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 621 | 3500 | 2607 | 12.9 | 120 | 10.4 | ||

| male: 60–64 y | 191 | 9.7 | 6.6 | 652 | 3700 | 2580 | 13.1 | 121 | 11.1 | ||

| male: 65–69 y | 173 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 720 | 3600 | 2396 | 12.2 | 134 | 10.4 | ||

| male: 70–74 y | 182 | 8.4 | 6.6 | 636 | 3400 | 2395 | 13.0 | 125 | 10.8 | ||

| Finland | The national FINDIET 2012 survey | 2012 | |||||||||

| female: 25–34 y | 243 | 5.3 | 8.2 | 1206 | 3500 | 2600 | 10.0 | 190 | 11.0 | ||

| female: 35–44 y | 233 | 5.1 | 9.0 | 1155 | 3400 | 2700 | 11.0 | 190 | 11.0 | ||

| female: 45–54 y | 230 | 4.9 | 8.2 | 952 | 3300 | 2500 | 10.0 | 190 | 10.0 | ||

| female: 55–64 y | 233 | 4.7 | 9.1 | 1002 | 3400 | 2500 | 10.0 | 190 | 10.0 | ||

| female: 65–74 y | 219 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 921 | 3200 | 2200 | 9.0 | 173 | 9.0 | ||

| male: 25–34 y | 277 | 6.9 | 10.7 | 1424 | 4200 | 3700 | 12.0 | 235 | 14.0 | ||

| male: 35–44 y | 272 | 7.3 | 11.5 | 1251 | 4100 | 3400 | 13.0 | 235 | 13.0 | ||

| male: 45–54 y | 277 | 8.0 | 11.2 | 1195 | 4200 | 3700 | 13.0 | 235 | 13.0 | ||

| male: 55–64 y | 257 | 6.4 | 11.9 | 1099 | 3900 | 3300 | 12.0 | 235 | 12.0 | ||

| male: 65–74 y | 255 | 6.7 | 12.8 | 1056 | 3900 | 3100 | 12.0 | 209 | 12.0 | ||

| France | INCA2 | 2006–2007 | |||||||||

| female: 18–79 y | 268 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 850 | 2681 | 2533 | 11.5 | 117 | 9.1 | ||

| male: 18–79 y | 307 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 984 | 3287 | 3447 | 14.9 | 136 | 12.4 | ||

| Germany | German National Nutrition Survey II | 2005–2007 | |||||||||

| female: 19–24 y | 318 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1039 | 2997 | 2355 | 11.6 | 173 | 9.1 | ||

| female: 25–34 y | 311 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 1061 | 3260 | 2533 | 12.6 | 192 | 9.8 | ||

| female: 35–50 y | 285 | 4.4 | 2.7 | 1067 | 3331 | 2579 | 12.8 | 200 | 9.8 | ||

| female: 51–64 y | 281 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 1011 | 3391 | 2522 | 12.6 | 204 | 9.6 | ||

| female: 65–80 y | 264 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 918 | 3125 | 2376 | 11.4 | 190 | 8.8 | ||

| male: 19–24 y | 394 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 1281 | 3812 | 3739 | 15.6 | 257 | 13.2 | ||

| male: 325–34 y | 372 | 6.9 | 3.5 | 1252 | 3890 | 3620 | 15.9 | 255 | 13.2 | ||

| male: 35–50 y | 337 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 1167 | 3939 | 3582 | 15.7 | 256 | 12.7 | ||

| male: 51–64 y | 316 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 1071 | 3769 | 3346 | 14.7 | 246 | 11.7 | ||

| male: 65–80 y | 282 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 970 | 3498 | 3058 | 13.6 | 232 | 10.9 | ||

| Hungary | Hungarian Dietary Survey 2009 | 2009 | |||||||||

| female: 19–30 y | 130 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 691 | 2600 | 5000 | 9.6 | 7.9 | |||

| female: 31–60 y | 133 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 647 | 2600 | 5200 | 9.7 | 7.7 | |||

| female: 60+ | 129 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 636 | 2600 | 4900 | 9.2 | 7.0 | |||

| male: 19–30 y | 167 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 772 | 3200 | 7100 | 12.8 | 10.6 | |||

| male: 31–60 y | 166 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 698 | 3200 | 7400 | 12.9 | 10.5 | |||

| male: 60+ | 142 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 635 | 2900 | 6200 | 11.1 | 8.8 | |||

| Iceland | The Diet of Icelanders—a national dietary survey 2010–2011 | 2010–2011 | |||||||||

| female: 18–30 y | 270 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 930 | 2543 | 2677 | 10.3 | 116 | 9.4 | ||

| female: 31–60 y | 259 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 840 | 2708 | 2631 | 9.7 | 138 | 9.1 | ||

| female: 61–80 y | 209 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 694 | 2517 | 2474 | 8.2 | 168 | 7.8 | ||

| male: 18–30 y | 343 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 1215 | 3429 | 4057 | 13.3 | 169 | 13.9 | ||

| male: 31–60 y | 309 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 1047 | 3489 | 3775 | 12.9 | 200 | 12.4 | ||

| male: 61–80 y | 258 | 10.8 | 13.4 | 847 | 3308 | 3520 | 11.0 | 204 | 11.2 | ||

| Ireland | National adult nutrition survey | 2008–2010 | |||||||||

| female: 18–64 y | 339 | 8.0 | 3.9 | 824 | 2690 | 2268 | 13.7 | 9.0 | |||

| female: 18–35 y | 337 | 11.1 | 3.1 | 794 | 2507 | 2385 | 15.1 | 8.5 | |||

| female: 36–50 y | 301 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 824 | 2781 | 2220 | 12.8 | 8.7 | |||

| female: 51–64 y | 399 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 874 | 2855 | 2145 | 12.8 | 10.1 | |||

| female: 65+ y | 357 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 995 | 2721 | 2035 | 13.8 | 10.7 | |||

| male: 18–64 y | 407 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 1060 | 3491 | 3122 | 15.1 | 11.8 | |||

| male: 18–35 y | 426 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 1122 | 3568 | 3291 | 15.6 | 12.4 | |||

| male: 36–50 y | 383 | 7.4 | 4.7 | 1036 | 3463 | 3123 | 14.8 | 11.6 | |||

| male: 51–64 y | 404 | 7.2 | 5.7 | 981 | 3388 | 2817 | 14.3 | 11.2 | |||

| male: 65+ y | 427 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 908 | 3038 | 2689 | 18.1 | 10.2 | |||

| Italy | The third Italian National food consumption survey INRAN-SCAI | 2005–2006 | |||||||||

| female: 18–64.9 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 730 | 2861 | 10.4 | 10.6 | |||||

| female: 65+ | 4.4 | 1.8 | 754 | 2822 | 10.0 | 9.9 | |||||

| male: 18–64.9 | 6.6 | 2.6 | 799 | 3218 | 12.6 | 12.6 | |||||

| male: 65+ | 6.5 | 2.5 | 825 | 3300 | 13.2 | 12.2 | |||||

| Latvia | Latvian National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2009 | 2007–2009 | |||||||||

| female: ALL | 457 | 2250 | 9.1 | 53 | 7.2 | ||||||

| male: ALL | 555 | 2868 | 12.1 | 68 | 10.1 | ||||||

| female: 17–26 y | 218 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 2240 | |||||||

| female: 27–36 y | 214 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 1920 | |||||||

| female: 37–46 y | 213 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 2640 | |||||||

| female: 47–56 y | 212 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 2320 | |||||||

| female: 57–64 y | 208 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 2160 | |||||||

| male: 17–26 y | 218 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 3480 | |||||||

| male: 27–36 y | 214 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 3960 | |||||||

| male: 37–46 y | 213 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 3680 | |||||||

| male: 47–56 y | 212 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 3400 | |||||||

| male: 57–64 y | 208 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 3600 | |||||||

| Lithuania | Study and evaluation of actual nutrition and nutrition habits of Lithuanian adult population | 2013–2014 | |||||||||

| female: 19–75 y | 481 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 535 | 2556 | 2842 | 10.3 | 30 | 8.1 | ||

| male: 19–75 y | 366 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 506 | 2322 | 2348 | 8.9 | 28 | 7.0 | ||

| all: 19–34 y | 643 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 576 | 2887 | 2538 | 12.2 | 33 | 9.6 | ||

| all: 35–49 y | 350 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 575 | 2654 | 245 | 10.7 | 30 | 8.6 | ||

| all: 50–64 y | 459 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 531 | 2625 | 2935 | 10.7 | 32 | 8.3 | ||

| all: 65–75 y | 669 | 1.2 | 4.9 | 518 | 2519 | 2882 | 10.0 | 30 | 7.7 | ||

| The Netherlands | Dutch National Food Consumption Survey (DNFCS) 2007–2010 | 2007–2010 | |||||||||

| female: 19–30 y | 232 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 954 | 2847 | 2429 | 9.3 | 156 | 9.2 | ||

| female: 31–50 y | 243 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 993 | 3112 | 2428 | 10.1 | 158 | 9.5 | ||

| female: 51–69 y | 281 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 1031 | 3296 | 2301 | 10.4 | 160 | 9.9 | ||

| male: 19–30 y | 293 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 1133 | 3774 | 3394 | 11.6 | 210 | 12.0 | ||

| male: 31–50 y | 302 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 1171 | 4048 | 3177 | 12.4 | 202 | 12.5 | ||

| male: 51–69 y | 330 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 1149 | 3866 | 2920 | 11.8 | 192 | 12.3 | ||

| Norway | Norkost3 | 2010–2011 | |||||||||

| female: 18–70 y | 231 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 811 | 3400 | 2500 | 9.9 | ||||

| male: 18–70 y | 279 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 1038 | 4200 | 3600 | 13.0 | ||||

| female: 18–29 y | 219 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 834 | 3100 | 2500 | 9.4 | ||||

| female: 30–39 y | 247 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 836 | 3400 | 2600 | 11.0 | ||||

| female: 40–49 y | 231 | 6.1 | 5.0 | 828 | 3400 | 2600 | 10.0 | ||||

| female: 50–59 y | 233 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 784 | 3500 | 2500 | 10.0 | ||||

| female: 60–70 y | 224 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 768 | 3400 | 2300 | 9.3 | ||||

| male: 18–29 y | 314 | 8.9 | 5.5 | 1248 | 4300 | 4000 | 14.0 | ||||

| male: 30–39 y | 295 | 8.9 | 6.1 | 1202 | 4200 | 4000 | 13.0 | ||||

| male: 40–49 y | 257 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 1009 | 4200 | 3500 | 12.0 | ||||

| male: 50–59 y | 275 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 955 | 4300 | 3500 | 12.0 | ||||

| male: 60–70 y | 269 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 900 | 4300 | 3100 | 12.0 | ||||

| Portugal | National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF) | 2015–2016 | |||||||||

| female: 18–64 y | 245.7 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 731 | 2990 | 2690 | 10.9 | 9.4 | |||

| female: 65–84 y | 260.1 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 724 | 3044 | 2449 | 10.3 | 8.3 | |||

| male: 18–64 y | 285.7 | 5.7 | 4.1 | 830 | 3901 | 3700 | 14.2 | 12.4 | |||

| male: 65–84 y | 264.6 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 764 | 3639 | 3260 | 13.4 | 10.2 | |||

| Spain | ENIDE 2011 | 2009–2010 | |||||||||

| female: 18–24 y | 234 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 789 | 2590 | 2328 | 12.5 | 75 | 8.6 | ||

| female: 25–44 y | 265 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 851 | 2838 | 2420 | 14.1 | 87 | 8.8 | ||

| female: 45–64 y | 281 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 839 | 3007 | 2283 | 13.8 | 87 | 8.7 | ||

| male: 18–24 y | 287 | 7.7 | 4.1 | 958 | 2905 | 2756 | 15.9 | 95 | 11.2 | ||

| male: 25–44 y | 288 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 898 | 2998 | 2730 | 16.1 | 100 | 10.4 | ||

| male: 45–64 y | 309 | 8.1 | 4.3 | 840 | 3160 | 2652 | 16.2 | 103 | 10.1 | ||

| Sweden | Riksmaten 2010–11 Swedish Adult Dietary Survey | 2010–2011 | |||||||||

| female: 18–30 y | 223 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 806 | 2659 | 2767 | 8.9 | 9.2 | |||

| female: 31–44 y | 247 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 849 | 2865 | 2876 | 9.7 | 9.9 | |||

| female: 45–64 y | 263 | 5.0 | 6.6 | 805 | 2971 | 2755 | 9.9 | 9.7 | |||

| female: 65–80 y | 275 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 826 | 3013 | 2546 | 9.4 | 9.1 | |||

| male: 18–30 y | 244 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 975 | 3139 | 3649 | 10.8 | 12.6 | |||

| male: 31–44 y | 263 | 5.5 | 6.9 | 991 | 3433 | 3819 | 11.7 | 13.0 | |||

| male: 45–64 y | 271 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 937 | 3523 | 3638 | 11.9 | 12.6 | |||

| male: 65–80 y | 279 | 6.6 | 9.1 | 885 | 3392 | 3214 | 11.0 | 10.9 | |||

| Turkey | Turkey nutrition and health survey 2010 (TNHS) | 2010 | |||||||||

| female: 19–30 y | 308 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 566 | 2211 | 1596 | 9.9 | 57 | 8.4 | ||

| female: 31–50 y | 334 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 605 | 2311 | 1686 | 10.4 | 60 | 8.6 | ||

| female: 51–64 y | 335 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 606 | 2357 | 1636 | 10.3 | 59 | 8.2 | ||

| female: 65–74 y | 296 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 547 | 2063 | 1572 | 9.5 | 53 | 7.6 | ||

| female: 75+ y | 271 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 495 | 1855 | 1426 | 8.1 | 49 | 6.3 | ||

| male: 19–30 y | 385 | 4.4 | 1.1 | 676 | 2511 | 2411 | 12.4 | 67 | 11.2 | ||

| male: 31–50 y | 410 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 744 | 2717 | 2353 | 13.0 | 74 | 11.5 | ||

| male: 51–64 y | 400 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 713 | 2687 | 2197 | 12.2 | 68 | 10.3 | ||

| male: 65–74 y | 375 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 677 | 2537 | 1938 | 11.1 | 64 | 9.2 | ||

| male: 75+ y | 329 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 593 | 2192 | 1811 | 10.2 | 55 | 8.4 | ||

| UK | National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) Years 1–4 | 2008–2012 | |||||||||

| female: 19–64 | 228 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 728 | 2532 | 1995 | 9.6 | 140 | 7.6 | ||

| female: 65+ y | 241 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 796 | 2649 | 2680 | 9.4 | 169 | 7.6 | ||

| male: 19–64 | 287 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 888 | 3039 | 2600 | 11.7 | 180 | 9.7 | ||

| male: 65+ y | 295 | 7.6 | 3.9 | 924 | 3063 | 3480 | 11.1 | 213 | 9.2 | ||

| all: 19–64 | 258 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 807 | 2785 | 2297 | 10.7 | 160 | 8.6 | ||

| all: 65+ y | 265 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 852 | 2831 | 3040 | 10.2 | 188 | 8.3 |

References

- WHO. European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alwan, A. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Amann, M.; Andersson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Fahimi, S.; Shi, P.; Powles, J.; Mozaffarian, D.; Global Burden of Diseases Chronic Expert Group. Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: A systematic assessment. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e132–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippin, H.L.; Hutchinson, J.; Evans, C.E.; Jewell, J.; Breda, J.J.; Cade, J.E. How much do we know about dietary intake across Europe? A review and characterisation of national surveys. Food Nutr. Res. 2017. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Novaković, R.; Cavelaars, A.E.J.M.; Bekkering, G.E.; Roman-Vinas, B.; Ngo, J.; Gurinovic, M.; Glibetic, M.; Nikolic, M.; Golesorkhi, M.; Medina, M.W. Micronutrient intake and status in Central and Eastern Europe compared with other European countries, results from the EURRECA network. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 824–840. [Google Scholar]

- Del Gobbo, L.C.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Shi, P.; Smith, M.; Myers, S.S.; Mozaffarian, D. Assessing global dietary habits: A comparison of national estimates from the FAO and the Global Dietary Database. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFCOSUM. European Food Consumption Survey Method Final Report; TNO Nutrition and Food Research: Zeist, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Fahimi, S.; Lim, S.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Powles, J.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D. Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys. BMJ 2014, 348, g2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; WHO. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; WHO Technical Report Series 916; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; WHO. WHO Expert Consultation on Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements. Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guideline: Potassium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy. Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom: Report of the Panel on Dietary Reference Values of the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy; HM Stationery Office: London, UK, 1991.

- World Bank Group. Population, Total. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?page=2 (accessed on 14 July 2017).

- Ministeri de Salut, B.S.i.F. Evaluation of the Nutritional Status of the Andorran Population. Available online: http://www.salut.ad/images/microsites/AvaluacioNutricional_04-05/index.html (accessed on 28 February 2017).

- Elmadfa, I.; Hasenegger, V.; Wagner, K.; Putz, P.; Weidl, N.-M.; Wottawa, D.; Kuen, T.; Seiringer, G.; Meyer, A.L.; Sturtzel, B.; et al. Austrian Nutrition Report 2012; Institute of Nutrition: Vienna, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bel, S.; Van den Abeele, S.; Lebacq, T.; Ost, C.; Brocatus, L.; Stievenart, C.; Teppers, E.; Tafforeau, J.; Cuypers, K. Protocol of the Belgian food consumption survey 2014: Objectives, design and methods. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, K. Food Consumption Survey 2014–2015: Food Consumption, in Report 4; WIV-ISP: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, A.; Christensen, T.; Matthiesen, J.; Knudsen, V.K.; Rosenlund-Sorensen, M.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Hinsch, H.J.; Ygil, K.H.; Korup, K.; Saxholt, E.; et al. Danskernes Kostvaner 2011–2013; DTU Fødevareinstitute: Søborg, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Helldán, A.; Raulio, S.; Kosola, M.; Tapanainen, H.; Ovaskainen, M.L.; Virtanen, S. Finravinto 2012—Tutkimus—The National FINDIET 2012 Survey; Raportti 2013_016; Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy: Tampere, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments (AFSSA). Étude Individuelle Nationale des Consommations Alimentaires 2 (INCA2) (2006–2007); AFSSA: Maisons-Alfort, France, 2009; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, B.M.; Heuer, T.; Hoffmann, I. The German Nutrient Database: Effect of different versions on the calculated energy and nutrient intake of the German population. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 42, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nationale Verzehrsstudie II. Ergebnisbericht Teil 1; Max Rubner-Institut Karlsruhe: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bíró, L.; Szeitz-Szabo, M.; Biro, G.; Sali, J. Dietary survey in Hungary, 2009. Part II: Vitamins, macro- and microelements, food supplements and food allergy. Acta Aliment. 2011, 40, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeitz-Szabó, M.; Biro, L.; Biro, G.; Sali, J. Dietary survey in Hungary, 2009. Part I. Macronutrients, alcohol, caffeine, fibre. Acta Aliment. 2011, 40, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingrimsdottir, L.; Valgeirsdottir, H.; Halldorsson, P.I.; Gunnarsdottir, I.; Gisladottir, E.; Porgeirsdottir, H.; Prosdottir, I. National nutrition surveys and dietary changes in Iceland. Læknablaðið 2014, 100, 659–664. [Google Scholar]

- Þorgeirsdóttir, H.; Valgeirsdottir, H.; Gunnarsdottir, I.; Gisladottir, E.; Gunnarsdottir, B.E.; Porsdottir, I.; Stefansdottir, J.; Steingrimsdottir, L. Hvað Borða Íslendingar? Könnun á Mataræði Íslendinga 2010–2011 Helstu Niðurstöður; Embætti landlæknis, Matvælastofnun, Rannsóknastofa í næringarfræði við Háskóla Íslands, Landspítala-háskólasjúkrahús: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance (IUNA). National Adult Nutrition Survey: Summary Report on Food and Nutrient Intakes, Physical Measurements, Physical Activity Patterns and Food Choice Motives; Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; McNulty, B.A.; Tiernery, A.M.; Devlin, N.F.C.; Joyce, T.; Leite, J.C.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J.; Brennan, L.; Gibney, M.J. Dietary fat intakes in Irish adults in 2011: How much has changed in 10 years? Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1798–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sette, S.; Le Donne, C.; Piccinelli, R.; Arcella, D.; Turrini, A.; Leclercq, C. The third Italian National Food Consumption Survey, INRAN-SCAI 2005-06—Part 1: Nutrient intakes in Italy. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joffe, R.; Ozolins, G.; Santare, D.; Bartkevics, V.; Mike, L.; Briska, I. The National Food Consumption Survey of LATVIA, 2007–2009; National Diagnostic Centre, Food and Veterinary Service Food Centre, Eds.; Zemkopibas Ministrija: Riga, Latvia, 2009.

- Barzda, A.; Bartkeviciute, R.; Baltusyte, I.; Stukas, R.; Bartkeviciute, S. Suaugusių ir pagyvenusių Lietuvos gyventojų faktinės mitybos ir mitybos įpročių tyrimas. Visuom. Sveik. 2016, 72, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rossum, C.; Fransen, H.P.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Buurma, E.M.; Ocke, M. Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2010: Part 6 Micronutrients; RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Van Rossum, C.; Fransen, H.P.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Buurma, E.M.; Ocke, M. Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2010: Part 5 Macronutrients; RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Van Rossum, C.; Fransen, H.P.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Buurma-Rethans, E.J.M.; Ocke, M.C. Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2010: Diet of Children and Adults Aged 7 to 69 Years; RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Totland, T.; Melnaes, B.K.; Lundberg-Hallen, N.; Helland-Kigen, K.M.; Lund-Blix, N.A.; Myhre, J.B.; Johansen, A.M.W.; Loken, E.B.; Andersen, L.F. Norkost 3. En Landsomfattende Kostholdsundersøkelse Blant Menn og Kvinner i Norge i Aldermen; Helsedirektoratet: Oslo, Norway, 2012; pp. 18–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcao, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Ramos, E.; Rodrigues, S.; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física (IAN-AF), 2015–2016 Part 1 Methodological Report; University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcao, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física (IAN-AF), 2015–2016 Part 2 Report; University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- AESAN; ENIDE. Encuesta Nacional de Ingesta Dietética Española 2011; Ministerio de Sanidad, Politica Social e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AESAN. Evaluación Nutricional de la Dieta Española. i Energía y Macronutrientes Sobre Datos de la Encuesta Nacional de Ingesta Dietética (ENIDE); Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- AESAN. Evaluación Nutricional de la Dieta Española. ii Micronutrientes Sobre Datos de la Encuesta Nacional de Ingesta Dietética (ENIDE); Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- Estévez-Santiago, R.; Beltrán-de-Miguel, B.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Assessment of dietary lutein, zeaxanthin and lycopene intakes and sources in the spanish survey of dietary intake (2009–2010). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amcoff, E. Riksmaten-Vuxna 2010–2011 Livsmedels-Och Näringsintag Bland Vuxna i Sverige; Livsmedelsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012.

- Güler, S.; Budakoglu, I.; Besler, H.T.; Pekcan, A.G.; Turkyilmaz, A.S.; Cingi, H.; Buzgan, T.; Zengin, N.; Dilmen, U.; Tosun, N.; et al. Methodology of National Turkey Nutrition and Health survey (TNHS) 2010. Med. J. Islam. World Acad. Sci. 2014, 22, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkey Ministry of Health. Türkiye Beslenme ve Sağlık Araştırması 2010: Beslenme Durumu ve Alışkanlıklarının Değerlendirilmesi Sonuç Raporu; Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Sağlık Bakanlığı Sağlık: Ankara, Turkey, 2014.

- Bates, B.; Lennox, A.; Prentice, A.; Bates, C.; Page, P.; Nicholson, S.; Swan, G. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Combined of the Rolling Program (2008/9–2011/12); Public Health England: London, UK, 2014.

- Lavie, C.J.; Milani, R.V.; Mehra, M.R.; Ventura, H.O. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bath, S.C.; Steer, C.D.; Golding, J.; Emmett, P.; Rayman, M.P. Effect of inadequate iodine status in UK pregnant women on cognitive outcomes in their children: Results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Lancet 2013, 382, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poslusna, K.; Ruprich, J.; de Vries, J.H.M.; Jakubikova, M.; van’t Veer, P. Misreporting of energy and micronutrient intake estimated by food records and 24 hour recalls, control and adjustment methods in practice. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, S73–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wilson, P.W.; Kannel, W.B. Beyond established and novel risk factors lifestyle risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2008, 117, 3031–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoops, K.T.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; Kromhout, D.; Perrin, A.-E.; Moreiras-Varela, O.; Menotti, A.; Van Staveren, W.A. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: The HALE project. JAMA 2004, 292, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, F.; Cesari, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: Meta-analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health (DH). F3(a). Non use of artificial trans fat; Department of Health: London, UK, 2014.

- Restrepo, B.J.; Rieger, M. Denmark’s policy on artificial trans fat and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temme, E.H.; Millenaar, I.L.; Van Donkersgoed, G.; Westenbrink, S. Impact of fatty acid food reformulations on intake of Dutch young adults. Acta Cardiol. 2011, 66, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Eliminating Trans Fats in Europe. A Policy Brief. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark. 2015. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/288442/Eliminating-trans-fats-in-Europe-A-policy-brief.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 5 April 2016).

- Crispim, S.; de Vries, J.H.M.; Geelen, A.; Souverein, O.W.; Hulshof, P.J.M.; Lafay, L.; Rousseau, A.-S.; Lillegaard, I.T.L.; Andersen, L.F.; Huybrechts, I.; et al. Biomarker-based evaluation of two 24-h recalls for comparing usual fish, fruit and vegetable intakes across European centers in the EFCOVAL Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; UNICEF. Iodine Deficiency in Europe: A Continuing Public Health Problem; Anderson, M., de Benoist, B., Darnton-Hill, I., Delange, F., Eds.; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- DH. F2. Salt Reduction Pledge. 2011. Available online: https://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/ledges/pledge/?pl=9 (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- WHO. Successful Nutrition Policies—Country Examples; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Brinsden, H.; MacGregor, G. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: A successful experiment in public health. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M.; Karumbunathan, V.; Zimmermann, M.B. Global iodine status in 2011 and trends over the past decade. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagt, S. Nordic Dietary Surveys: Study Designs, Methods, Results and Use in Food-Based Risk Assessments; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mensink, G.; Fletcher, R.; Gurinovic, M.; Huybrechts, I.; Lafay, L.; Serra-Majem, L.; Szponar, L.; Tetens, I.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Baka, A. Mapping low intake of micronutrients across Europe. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busby, A.; Abramsky, L.; Dolk, H.; Armstrong, B. Preventing neural tube defects in Europe: Population based study. BMJ 2005, 330, 574–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, K.W.; Guenther, P.M.; Freedman, L.S.; Subar, A.F.; Kipnis, V.; Midthune, D.; Tooze, J.A.; Krebs-Smith, S.M. Statistical methods for estimating usual intake of nutrients and foods: A review of the theory. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongeau, R.; Brassard, R. A comparison of three methods for analyzing dietary fiber in 38 foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1989, 2, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merten, C.; Ferrari, P.; Bakker, M.; Boss, A.; Hearty, A.; Leclercq, C.; Lindtner, O.; Tlustos, C.; Verger, P.; Volatier, J.-L. Methodological characteristics of the national dietary surveys carried out in the European Union as included in the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2011, 28, 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.; Rippin, H.; Jewell, J.; Breda, J.; Cade, J.E. Comparison of high and low trans fatty acid consumers: Analyses of UK National Diet and Nutrition Surveys before and after product reformulation. Public Health Nutr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, B.; Nelson, M. The strengths and weaknesses of dietary survey methods in materially deprived households in England: A discussion paper. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Included | Excluded |

|---|---|

| Surveys conducted at an individual level | Surveys collected at group i.e. household level |

| Nationally representative surveys | Non-nationally representative, regional only surveys |

| Results of surveys reported by published and unpublished reports, academic journals and websites | Surveys with data collected prior to 1990 |

| Surveys that included individuals >2 y | Surveys with samples exclusively <2 y |

| Surveys based on whole diet rather than specific food groups | Surveys with incomplete food group coverage |

| Surveys with small sample sizes (n < 200) |

| Macronutrients | RNI | Micronutrients | RNI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (MJ and kcal) | N/A | Folic acid (μg) | Minimum |

| Carbohydrates (g and %Energy (E)) | Target | Vitamin B12 (μg) | Minimum |

| Sugars (g) | Maximum | Vitamin D (μg) | Target |

| Sucrose (g) | Maximum | Calcium (mg) | Minimum |

| Starches (g) | N/A | Potassium (mg) | Minimum |

| Fiber (g) | Target | Sodium (mg) | Maximum |

| Total fat (g) | Maximum | Iron (mg) | Minimum |

| Saturates (g) | Maximum | Iodine (μg) | Minimum |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) (g) | N/A | Zinc (mg) | Minimum |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (g) | Target | ||

| Trans Fatty Acids (TFAs) (g) | Maximum | ||

| Protein (g) | Target | ||

| Omega fatty acids (g) | Target |

| Country | Survey Name | Survey Year | Source * | Sample Size | Sample Age | Dietary Methodology | Nutrient Reference Database | Nutrient Intakes by SEG Y/N ** | WHO RNIs Not Met by All Age Groups (%) Ϯ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andorra | Evaluation of the Nutritional Status of the Andorran Population | 2004–2005 | 4 | 900 | 12–75 | 24 h recall (×2 for 35% sample), FFQ | CESNID. Tablas de composición de alimentos. Barcelona: Edicions Universitat de Barcelona-Centre d’Ensenyament Superior de Nutrició i Dietètica, 2002 | N | 83 | [17] |

| Austria | Austrian nutrition report 2012 (OSES) | 2010–2012 | 2 | 1002 | 7–14; 18–80 | 3-day diary (consecutive) (children); 2*24 h recall (adults). | Analysis run with software “(nut.s) science” based on Bundeslebensmittelschlüssel 3.01/Goldberg cut-offs for data cleaning | N | 72 | [18] |

| Belgium | Belgium National Food Consumption Survey (BNFCS) 2014 | 2014–2015 | 1/2 | 3146 | 3–64 | 2*24 h recall | The NIMS Belgian Table of Food Composition (Nubel); Dutch NEVO | N | 78 | [19,20] |

| Denmark | Danish National Survey of Diet and Physical Activity (DANSDA) 2011–2013 | 2011–2013 | 2 | 3946 | 4–75 | 7-day diary (consecutive) | Danish Food Composition Databank | N | 67 | [21] |

| Estonia | National Dietary Survey | 2014–2015 | 1 | 4906 | 4 m–74 y | 2*24 h recall (age > 10); 2*24 h food diary (age < 10); FFQ (age > 2) | Y—income, poverty threshold, education | 78 | ||

| Finland | The National FINDIET 2012 survey (FINRISK) | 2012 | 2 | 1708 | 25–74 | 48 h recall | Fineli 7 Food Composition Database | Y—education | 61 | [22] |

| France | Individual National Food Consumption Survey (INCA2) | 2006–2007 | 2 | 4079 | 3–79 | 7-day diary (consecutive) | Food Composition Database of CIQUAL of Afssa | Y—education | 83 | [23] |

| Germany | German National Nutrition Survey (Nationale Verzehrstudie) II (NVSII) | 2005–2007 | 1/3 | 15,371 | 14–80 | DISHES diet history interview, 24 h-recall, diet weighing diary (2*4 days) | Bundeslebensmittelschlüssel (BLS) | N | 78 | [24,25] |

| Hungary | Hungarian dietary survey 2009 | 2009 | 2 | 3077 | 19–30, 31–60, 60+ | 3-day diary, FFQ, | Új tápanyagtáblázat | N | 72 | [26,27] |

| Iceland | The Diet of Icelanders—a national dietary survey 2010–2011 | 2010–2011 | 1 | 1312 | 18–80 | 2*24 h recall + FFQ | Icelandic Database of Food Ingredients (ÍSGEM); Public Health Institute for Raw Materials in the Icelandic Market | N | 72 | [28,29] |

| Ireland | National adult nutrition survey 2011 (NANS) | 2008–2010 | 1 | 1500 | 18–90 | 4-day semi weighed food diary (consecutive) | McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods 5&6 editions | Y—social class and education | 72 | [30,31] |

| Italy | The third Italian National food consumption survey INRAN-SCAI 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 2 | 3323 | 0.1–97.7 | 3-day diary (consecutive) | Banca Dati di Composizione degli Alimenti | N | 83 | [32] |

| Latvia | Latvian National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2009 | 2008 | 1 | 1949 | 7–64 | 2*24 h recall, FFQ | Latvian National Food Composition Database 2009 | N | 78 | [33] |

| Lithuania | Study of actual nutrition and nutrition habits of Lithuanian adult population | 2013–2014 | 1 | 2513 | 19–75 | 24 h recall + questionnaire | EuroFIR Food Classification | N | 83 | [34] |

| The Netherlands | Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2010 (DNFCS 2007–2010) | 2007–2010 | 1/2 | 3819 | 7–69 | 2*24 h recalls | Dutch Food Composition Database (NEVO) | Y—education | 61 | [35,36,37] |

| Norway | Norwegian national diet survey NORKOST3 | 2010–2011 | 2 | 1787 | 18–70 | 2*24 h recall and FFQ | The Norwegian Food Composition Tables | Y—education | 83 | [38] |

| Portugal | National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF) | 2015–2016 | 4 | 4221 | 3 m–84 y | 2*24 h recall (non-consecutive) and FPQ (electronic interview) 2-day food diary for children <10 y | Portuguese Food Composition Table (INSA) | N | 78 | [39,40] |

| Spain | ENIDE study (Sobre datos de la Encuesta Nacionalde Ingesta Dietética) | 2009–2010 | 2 | 3000 | 18–24; 25–44; 45–64 | 3-day diary + 24 h recall (consecutive) | Tablas de Composición de Alimentos, 15th ed | N | 83 | [41,42,43,44] |

| Sweden | Riksmaten 2010–2011 Swedish Adults Dietary Survey | 2010–2011 | 2 | 1797 | 18–80 | 4-day food diary (consecutive) | NFA Food Composition Database | N | 78 | [45] |

| Turkey | Turkey nutrition and health survey 2010 (TNHS) | 2010 | 2 | 14,248 | 0–100 | 24 h recall, FFQ | BEBS Nutritional Information System Software; Turkish Food Composition Database | N | 78 | [46,47] |

| UK | National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS RP 2008–2012) | 2008–2012 | 2 | 6828 | 1.5–94 | 4-day diary (consecutive) | McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods integrated dataset | Y—income | 72 | [48] |

| COUNTRY | Energy (MJ) | Protein (g) | CHO (g) | Sugars (g) | Sucrose (g) | Starch (g) | Fibre (g) | Total Fat (g) | Saturates (g) | MUFA (g) | PUFA (g) | TFA (g) | n-3 (g) | n-6 (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | National Dietary Survey 2014–2015 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 6.7 | 64 | 194 | 17 | 65 | 26 | 24 | 11 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 8.2 | |||

| Male | 8.7 | 86 | 235 | 19 | 83 | 32 | 31 | 14 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 10.9 | |||

| Hungary | Hungarian Dietary Survey 2009 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 8.9 | 79 | 253 | 44 | 21 | 87 | 26 | 27 | 22 | 0.9 | 21.6 | |||

| Male | 12.0 | 106 | 315 | 50 | 25 | 122 | 36 | 40 | 29 | 1.2 | 28.4 | |||

| Latvia | Latvian National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2009 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 6.4 | 55 | 190 | 16 | 68 | 28 | 24 | 11 | ||||||

| Male | 8.9 | 79 | 246 | 20 | 93 | 38 | 33 | 15 | ||||||

| Lithuania | Study and evaluation of actual nutrition and nutrition habits of Lithuanian adult population 2013–2014 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 6.5 | 56 | 178 | 56 | 15 | 71 | 22 | 27 | 16 | |||||

| Male | 9.2 | 75 | 224 | 55 | 17 | 108 | 34 | 41 | 24 | |||||

| Turkey | Turkey nutrition and health survey 2010 (TNHS) | |||||||||||||

| Female | 6.5 | 50 | 197 | 20 | 61 | 20 | 22 | 16 | 1.1 | 14.5 | ||||

| Male | 8.6 | 67 | 260 | 23 | 78 | 26 | 28 | 19 | 1.4 | 17.4 | ||||

| CEEC TOTAL Female | 6.7 | 53 | 202 | 56 | 44 | 20 | 64 | 21 | 23 | 16 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 15.2 | |

| CEEC TOTAL Male | 9.0 | 72 | 264 | 55 | 50 | 23 | 84 | 28 | 30 | 20 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 18.5 | |

| Denmark | Danish Dietary habits 2011–2013 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 8.4 | 76 | 211 | 43 | 21 | 83 | 33 | 31 | 13 | 1.3 | ||||

| Male | 11.2 | 101 | 269 | 56 | 24 | 111 | 45 | 41 | 17 | 1.7 | ||||

| Finland | The national FINDIET 2012 survey | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.0 | 70 | 181 | 42 | 21 | 67 | 26 | 24 | 12 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 8.7 | ||

| Male | 9.1 | 91 | 225 | 49 | 22 | 88 | 34 | 32 | 15 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 11.0 | ||

| Iceland | The Diet of Icelanders—a national dietary survey 2010–2011 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.4 | 76 | 188 | 87 | 16 | 72 | 29 | 23 | 12 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 9.0 | ||

| Male | 10.0 | 106 | 240 | 104 | 18 | 99 | 40 | 32 | 16 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 11.9 | ||

| Norway | Norkost3 2010–2011 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 8.0 | 81 | 205 | 36 | 22 | 75 | 29 | 25 | 14 | |||||

| Male | 10.9 | 112 | 278 | 48 | 27 | 102 | 39 | 34 | 19 | |||||

| Sweden | Riksmaten 2010–2011 Swedish Adult Dietary Survey | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.4 | 72 | 193 | 37 | 19 | 70 | 27 | 26 | 12 | 2.5 | 8.6 | |||

| Male | 9.3 | 92 | 238 | 41 | 21 | 87 | 33 | 33 | 14 | 2.9 | 10.5 | |||

| NORTH TOTAL Female | 7.6 | 74 | 197 | 87 | 39 | 20 | 73 | 28 | 26 | 13 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 8.6 | |

| NORTH TOTAL Male | 10.0 | 98 | 250 | 104 | 47 | 23 | 95 | 37 | 35 | 16 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 10.7 | |

| Andorra | Evaluation of the nutritional status of the Andorran population 2004–2005 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 6.8 | 81 | 164 | 77 | 17 | 75 | 22 | 32 | 10 | |||||

| Male | 8.4 | 95 | 197 | 86 | 17 | 84 | 28 | 41 | 13 | |||||

| Austria | Austrian nutrition report 2010–2012 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.5 | 67 | 209 | 43 | 21 | 72 | 31 | 24 | 13 | 1.4 | 11.6 | |||

| Male | 8.9 | 79 | 235 | 48 | 21 | 86 | 37 | 28 | 14 | 1.5 | 12.3 | |||

| Belgium | The Belgian food consumption survey 2014–2015 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.9 | 71 | 202 | 94 | 18 | 77 | 28 | 28 | 14 | 0.8 | ||||

| Male | 10.9 | 95 | 274 | 124 | 20 | 102 | 36 | 37 | 18 | 1.0 | ||||

| France | INCA2 2006–2007 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.6 | 74 | 199 | 89 | 16 | 80 | 32 | 29 | 12 | |||||

| Male | 9.8 | 100 | 262 | 101 | 19 | 100 | 41 | 36 | 15 | |||||

| Germany | German National Nutrition Survey II 2005–2007 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.9 | 67 | 227 | 25 | 74 | |||||||||

| Male | 10.5 | 89 | 279 | 27 | 100 | |||||||||

| Ireland | National adult nutrition survey 2008–2010 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.1 | 70 | 198 | 81 | 18 | 66 | 29 | 27 | 14 | 1.0 | 1.6 | |||

| Male | 9.8 | 98 | 260 | 100 | 21 | 90 | 38 | 35 | 16 | 1.6 | 1.9 | |||

| Italy | The third Italian National food consumption survey INRAN-SCAI 2005–2006 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 8.0 | 75 | 236 | 79 | 18 | 77 | 24 | 37 | 10 | |||||

| Male | 9.9 | 92 | 282 | 85 | 20 | 94 | 29 | 46 | 12 | |||||

| The Netherlands | Dutch National Food Consumption Survey (DNFCS) 2007–2010 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 8.2 | 75 | 220 | 106 | 19 | 76 | 29 | 26 | 14 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 11.8 | ||

| Male | 11.1 | 98 | 291 | 128 | 23 | 103 | 38 | 36 | 20 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 17.0 | ||

| Portugal | National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF) 2015–2016 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 7.2 | 78 | 195 | 77 | 17 | 60 | 22 | 25 | 11 | 0.8 | 9.5 | |||

| Male | 9.8 | 106 | 246 | 85 | 20 | 77 | 27 | 32 | 13 | 1.0 | 12.3 | |||

| Spain ** | ENIDE 2011 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 9.2 | 88 | 199 | 72 | 19 | 93 | 26 | 39 | 13 | |||||

| Male | 9.8 | 109 | 242 | 76 | 21 | 115 | 33 | 48 | 15 | |||||

| UK | National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) Y1-4 2008–2012 | |||||||||||||

| Female | 6.7 | 65 | 195 | 85 | 13 | 60 | 22 | 21 | 10 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 8.6 | ||

| Male | 8.7 | 83 | 247 | 105 | 15 | 77 | 28 | 28 | 13 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 11.0 | ||

| WEST TOTAL Female | 7.8 | 73 | 212 | 84 | 43 | 19 | 75 | 26 | 30 | 12 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 9.5 | |

| WEST TOTAL Male | 9.8 | 94 | 264 | 96 | 48 | 21 | 96 | 33 | 38 | 14 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 12.2 | |

| EUROPE TOTAL Female | 7.6 | 69 | 209 | 84 | 41 | 19 | 73 | 25 | 28 | 13 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 11.9 | |

| EUROPE TOTAL Male | 9.7 | 90 | 264 | 96 | 48 | 21 | 94 | 32 | 36 | 16 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 14.9 | |

| SURVEY | Folic Acid (μg) | Vitamin B12 (μg) | Vitamin D (μg) | Calcium (mg) | Potassium (mg) | Sodium (mg) | Iron (mg) | Iodine (μg) | Zinc (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | National Dietary Survey 2014–2015 | ||||||||

| Female | 166 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 648 | 3037 | 1801 | 10.8 | 108 | 8.4 |

| Male | 198 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 767 | 3761 | 2562 | 13.6 | 134 | 11.4 |

| Hungary | Hungarian Dietary Survey 2009 | ||||||||

| Female | 131 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 651 | 2600 | 5086 | 9.5 | 7.5 | |

| Male | 161 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 701 | 3140 | 7100 | 12.5 | 10.2 | |

| Latvia | Latvian National Food Consumption Survey 2007–2009 | ||||||||

| Female | 214 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 457 | 2250 | 2283 | 9.1 | 53 | 7.2 |

| Male | 214 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 555 | 2868 | 3598 | 12.1 | 68 | 10.1 |

| Lithuania | Study and Evaluation of Actual Nutrition and Nutrition Habits of Lithuanian Adult Population 2013–2014 | ||||||||

| Female | 366 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 506 | 2322 | 2348 | 8.9 | 28 | 7.0 |

| Male | 643 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 576 | 2887 | 2538 | 12.2 | 33 | 9.6 |

| Turkey | Turkey Nutrition and Health Survey 2010 (TNHS) | ||||||||

| Female | 320 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 583 | 2242 | 1625 | 10.0 | 58 | 8.2 |

| Male | 393 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 704 | 2608 | 2552 | 12.3 | 69 | 10.7 |

| CEEC TOTAL Female | 298 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 586 | 2292 | 2019 | 9.9 | 58 | 8.1 |

| CEEC TOTAL Male | 370 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 698 | 2692 | 3041 | 12.3 | 69 | 10.6 |

| Denmark | Danish Dietary Habits 2011–2013 | ||||||||

| Female | 329 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 1038 | 3200 | 3200 | 10.0 | 227 | 10.5 |

| Male | 370 | 8.0 | 5.3 | 1188 | 3900 | 4400 | 13.0 | 268 | 14.1 |

| Finland | The National FINDIET 2012 Survey | ||||||||

| Female | 231 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 1040 | 3352 | 2492 | 10.0 | 186 | 10.2 |

| Male | 266 | 7.0 | 11.8 | 1178 | 4037 | 3400 | 12.4 | 228 | 12.7 |

| Iceland | The Diet of Icelanders—a National Dietary Survey 2010–2011 | ||||||||

| Female | 249 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 820 | 2632 | 2600 | 9.4 | 142 | 8.8 |

| Male | 304 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 1034 | 3433 | 3773 | 12.5 | 195 | 12.4 |

| Norway | Norkost3 2010–2011 | ||||||||

| Female | 231 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 811 | 3374 | 2510 | 10.0 | ||

| Male | 279 | 8.8 | 6.7 | 1038 | 4263 | 3558 | 12.5 | ||

| Sweden | Riksmaten 2010–2011 Swedish Adult Dietary Survey | ||||||||

| Female | 252 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 825 | 2887 | 2766 | 9.6 | ||

| Male | 266 | 6.0 | 7.6 | 945 | 3410 | 3591 | 11.5 | ||

| NORTH TOTAL Female | 260 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 912 | 3142 | 2751 | 9.8 | 205 | 10.3 |

| NORTH TOTAL Male | 291 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 1064 | 3812 | 3721 | 12.2 | 247 | 13.4 |

| Andorra | Evaluation of the Nutritional Status of the Andorran Population 2004–2005 | ||||||||

| Female | 241 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 790 | 2867 | 2495 | 10.8 | 8.1 | |

| Male | 255 | 7.4 | 4.1 | 831 | 3126 | 3086 | 13.3 | 9.9 | |

| Austria | Austrian Nutrition Report 2010–2012 | ||||||||

| Female | 206 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 771 | 2504 | 3027 | 10.6 | 133 | 9.3 |

| Male | 209 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 821 | 2775 | 3532 | 11.4 | 144 | 11.0 |

| Belgium | The Belgian Food Consumption Survey 2014–2015 | ||||||||

| Female | 190 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 720 | 2062 | 8.6 | 127 | ||

| Male | 226 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 821 | 2739 | 11.1 | 174 | ||

| France | INCA2 2006–07 | ||||||||

| Female | 268 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 850 | 2681 | 2533 | 11.5 | 117 | 9.1 |

| Male | 307 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 984 | 3287 | 3447 | 14.9 | 136 | 12.4 |

| Germany | German National Nutrition Survey II 2005–2007 | ||||||||

| Female | 285 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 1020 | 3272 | 2502 | 12.4 | 196 | 9.5 |

| Male | 327 | 6.4 | 3.9 | 1115 | 3779 | 3418 | 15.0 | 248 | 12.1 |

| Ireland | National Adult Nutrition Survey 2008–2010 | ||||||||

| Female | 342 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 851 | 2694 | 2231 | 13.7 | 9.2 | |

| Male | 410 | 7.2 | 4.7 | 1038 | 3426 | 3060 | 15.5 | 11.6 | |

| Italy | The third Italian National Food Consumption Survey INRAN-SCAI 2005–2006 | ||||||||

| Female | 5.3 | 2.2 | 735 | 2853 | 10.3 | 10.5 | |||

| Male | 6.6 | 2.6 | 803 | 3231 | 12.7 | 12.5 | |||

| The Netherlands | Dutch National Food Consumption Survey (DNFCS) 2007–2010 | ||||||||

| Female | 252 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 993 | 3086 | 2386 | 9.9 | 158 | 9.5 |

| Male | 308 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1151 | 3895 | 3165 | 11.9 | 201 | 12.3 |

| Portugal | National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF) 2015–2016 | ||||||||

| Female | 248 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 730 | 2999 | 2647 | 10.8 | 9.2 | |

| Male | 281 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 816 | 3845 | 3605 | 14.0 | 11.9 | |

| Spain ** | ENIDE 2011 | ||||||||

| Female | 266 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 835 | 2865 | 2347 | 13.7 | 85 | 8.7 |

| Male | 296 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 884 | 3049 | 2702 | 16.1 | 100 | 10.4 |

| UK | National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) Y1-4 2008–2012 | ||||||||

| Female | 231 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 743 | 2558 | 2148 | 9.6 | 146 | 7.6 |

| Male | 289 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 896 | 3044 | 2793 | 11.6 | 187 | 9.6 |

| WEST TOTAL Female | 259 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 846 | 2869 | 2405 | 11.3 | 143 | 9.1 |

| WEST TOTAL Male | 302 | 6.5 | 3.5 | 951 | 3349 | 3153 | 13.8 | 178 | 11.5 |

| EUROPE TOTAL Female | 268 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 799 | 2771 | 2341 | 10.9 | 127 | 8.9 |

| EUROPE TOTAL Male | 316 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 908 | 3245 | 3163 | 13.4 | 156 | 11.4 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rippin, H.L.; Hutchinson, J.; Jewell, J.; Breda, J.J.; Cade, J.E. Adult Nutrient Intakes from Current National Dietary Surveys of European Populations. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121288

Rippin HL, Hutchinson J, Jewell J, Breda JJ, Cade JE. Adult Nutrient Intakes from Current National Dietary Surveys of European Populations. Nutrients. 2017; 9(12):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121288

Chicago/Turabian StyleRippin, Holly L., Jayne Hutchinson, Jo Jewell, Joao J. Breda, and Janet E. Cade. 2017. "Adult Nutrient Intakes from Current National Dietary Surveys of European Populations" Nutrients 9, no. 12: 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121288

APA StyleRippin, H. L., Hutchinson, J., Jewell, J., Breda, J. J., & Cade, J. E. (2017). Adult Nutrient Intakes from Current National Dietary Surveys of European Populations. Nutrients, 9(12), 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121288