Modeling the Effect of Replacing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption with Water on Energy Intake, HBI Score, and Obesity Prevalence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Dietary Intake and Beverage Groups

2.3. Healthy Beverage Index

2.4. Anthropometrics

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sugar Sweetened Beverage Consumption

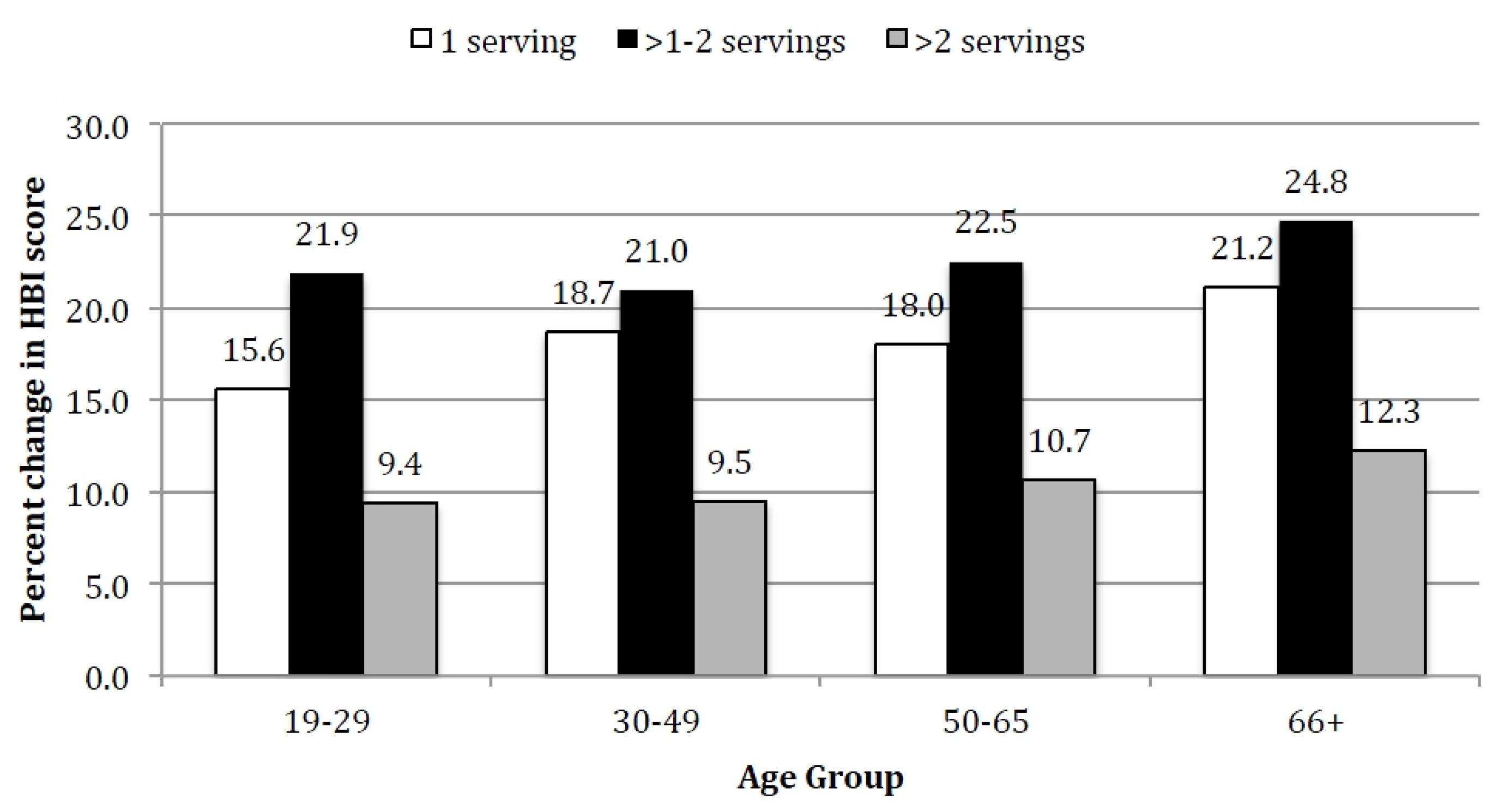

3.2. Impact on Healthy Beverage Index Scores

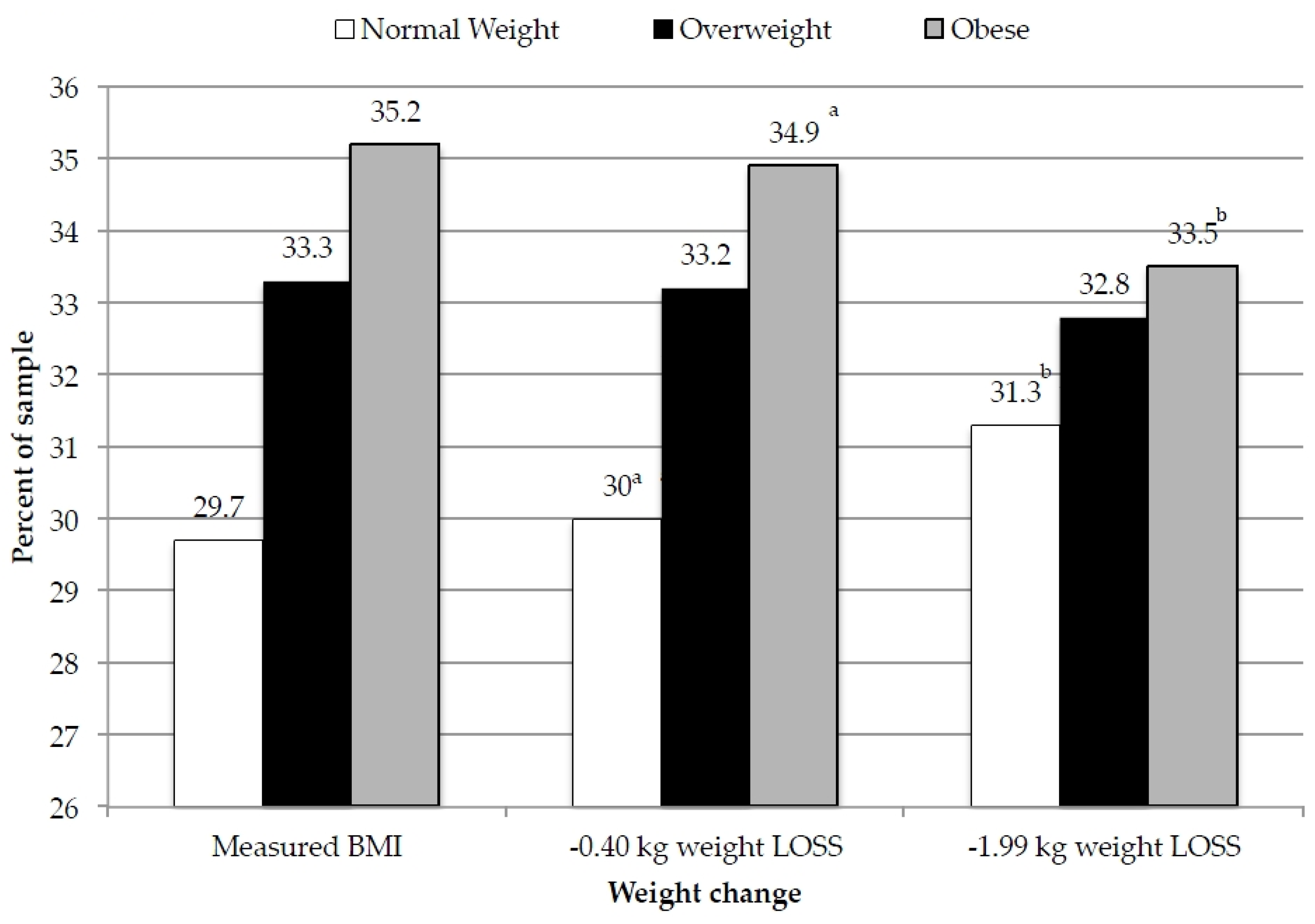

3.3. Predicted Impact on Overweight and Obesity Prevalence

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| FNDDS | Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies |

| HBI | Healthy Beverage Index |

| MEC | Mobile Exam Center |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| oz | Ounces |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SSB | sugar-sweetened beverages |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

References

- Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Hu, F. The role of high sugar foods and sugar-sweetened beverages in weight gain and obesity. In Managing and Preventing Obesity: Behavioral Factors and Dietary Interventions; Gill, T., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra, N.; Mars, M.; de Wijk, R.A.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; de Graaf, C. The effect of viscosity on ad libitum food intake. Int. J. Obes. Lond. 2008, 32, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassady, B.A.; Considine, R.V.; Mattes, R.D. Beverage consumption, appetite, and energy intake: What did you expect? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Hsu, W.H.; Hollis, J.H. The impact of food viscosity on eating rate, subjective appetite, glycemic response and gastric emptying rate. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.A.; Hamill, L.R.; Davies, S.; Rogers, P.J.; Brunstrom, J.M. Energy-dense snacks can have the same expected satiation as sugar-containing beverages. Appetite 2015, 95, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Bellisle, F. Liquid calories, sugar, and body weight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almiron-Roig, E.; Chen, Y.; Drewnowski, A. Liquid calories and the failure of satiety: How good is the evidence? Obes. Rev. 2003, 4, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B. Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC Report). Dietary Guidelines Website; Released February 23. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/pdfs/scientific-report-of-the-2015-dietary-guidelines-advisory-committee.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2015).

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Gregg, E.W.; Flanders, W.D.; Merritt, R.; Hu, F.B. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.S.; Schulze, M.B.; Hu, F.B. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance Summaries: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2005; MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006; Volume 55. [Google Scholar]

- Block, G. Foods contributing to energy intake in the US: Data from NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2000. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2006, 17, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; O’Connor, L.; Ye, Z.; Mursu, J.; Hayashino, Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Forouhi, N.G. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ 2015, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.; Popkin, B.; Bray, G.; Despres, J.; Hu, F. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010, 121, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, L.; Imamura, F.; Lentjes, M.A.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Prospective associations and population impact of sweet beverage intake and type 2 diabetes, and effects of substitutions with alternative beverages. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleich, S.N.; Wolfson, J.A. U.S. adults and child snacking patterns among sugar-sweetened beverage drinkers and non-drinkers. Prev. Med. 2016, 72, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kit, B.K.; Fakhouri, T.H.I.; Park, S.; Nielsen, S.J.; Ogden, C.L. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Powell, L.M. Consumption patterns of sugar sweetened beverages in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Lim, S.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D. Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk: A systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riebl, S.K.; Davy, B.M. The hydration equation: Update on water balance and cognitive performance. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2013, 17, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; D’Anci, K.E.; Rosenberg, I.H. Water hydration and health. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Malik, V.S.; Hao, T.; Willett, W.C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Hu, F.B. Changes in water and beverage intake and long-term weight changes: Results from three prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Obes. Lond. 2013, 37, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, E.A.; Davy, B.M. Beverage consumption and adult weight management: A review. Eat Behav. 2009, 10, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, R.; McCaffrey, J. Plain water consumption in relation to energy intake and diet quality among US adults, 2005–2012. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottled Water’s Rising Tide. Available online: http://www.beverageworld.com/articles/full/17371/bottled-waters-rising-tide (accessed on 7 March 2016).

- Hogan, C. Bottled Water Trends for 2014; Food Manufacturing: Madison, WI, USA, 2014; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Drink up Campaign. Available online: http://youarewhatyoudrink.org (accessed on 7 March 2016).

- Corporate Accountability International. Available online: http://www.stopcorporateabuse.org/campaigns/challenge-corporate-control-water/think-outside-bottle (accessed on 7 March 2016).

- 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Chapter 2: Shifts Need to Align with Healthy Eating Patterns. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/chapter-2/a-closer-look-at-current-intakes-and-recommended-shifts/ (accessed on 4 March 2016).

- Duffey, K.J.; Davy, B.M. The healthy beverage index is associated with reduced cardiometabolic risk in US adults: A preliminary analysis. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Armstrong, L.E.; Bray, G.M.; Caballero, B.; Frei, B.; Willett, W. A new proposed guidance system for beverage consumption in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, V.E.; Davy, B.M.; Myers, E.A.; You, W.; Zoellner, J.M. Changes in the healthy beverage index in response to an intervention targeting a reduction in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption as compared to an intervention targeting improvements in physical activity: Results from the talking health trial. Nutrients 2015, 7, 10168–10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial: Survey Design Factors Course. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/Nhanes/SurveyDesign/intro.htm (accessed on 4 March 2016).

- NHANES MEC Interviewers Procedures Manual. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_05_06/mec_interview.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2016).

- Key Concepts about NHANES Dietary Data Collection. Availble online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/Dietary/SurveyOrientation/DietaryDataOverview/Info2.htm (accessed on 4 March 2016).

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/services/docs.htm?docid=12089 (accessed on 7 March 2016).

- Slining, M.M.; Yoon, E.; Davis, J.; Hollingsworth, B.; Miles, D.; Ng, S.W. An approach to monitor food and nutrition from “factory to fork”. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Morenga, L.; Mallard, S.; Mann, J. Dietary sugars and body weight: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 2012, 345, e7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm (accessed on 7 March 2016).

- Davy, B.M.; Dennis, E.A.; Dengo, A.L.; Wilson, K.L.; Davy, K.P. Water consumption reduces energy intake at a breakfast meal in obese older adults. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Walleghen, E.L.; Orr, J.S.; Gentile, C.L.; Davy, B.M. Premeal water consumption reduces meal energy intake in older but not younger subjects. Obesity 2007, 15, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stookey, J.D.; Constant, F.; Gardner, C.D.; Popkin, B.M. Replacing sweetened caloric beverages with drinking water is associated with lower energy intake. Obesity 2007, 15, 3013–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Xu, F.; Town, M.; Blanck, H.M. Prevalence of sugar-sweetened beverage intake among adults—23 states and the district of Columbia, 2013. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; He, F.J.; Yin, Y.; Hashem, K.M.; MacGregor, G.A. Gradual reduction of sugar in soft drinks without substitution as a strategy to reduce overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes: A modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.C.; Popkin, B.M. Impact of water intake on energy intake and weight status: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Heitmann, B.L.; Rangan, A. Substitution of sugar-sweetened beverages with other beverage alternatives: A review of long-term health outcomes. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muckelbauer, R.; Sarganas, G.; Grüneis, A.; Müller-Nordhorn, J. Association between water consumption and body weight outcomes: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Cordero, S.; Popkin, B.M. Impact of a water intervention on sugar-sweetened beverage intake substitution by water: A clinical trial in overweight and obese Mexican women. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Cruz, A.; Gómez-Miranda, L.M.; Bacardí-Gascón, M. Randomized clinical trials of the effect of sugar sweetened beverages consumption on adiposity in youngers than 16 y old; systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28, 1797–1801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peters, J.C.; Beck, J.; Cardel, M.; Wyatt, H.R.; Foster, G.D.; Pan, Z.; Wojtanowski, A.C.; Vander Veur, S.S.; Herring, S.J.; Brill, C.; et al. The effects of water and non-nutritive sweetened beverages on weight loss and weight maintenance: A randomized clinical trial. Obesity 2016, 24, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, D.F.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Lyons, E.; Stevens, J.; Erickson, K.; Polzien, K.; Diamond, M.; Wang, X.; Popkin, B.M. Replacing caloric beverages with water or diet beverages for weight loss in adults: Main results of the Choose Healthy Options Consciously Everyday (CHOICE) randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piernas, C.; Tate, D.F.; Wang, X.; Popkin, B.M. Does diet-beverage intake affect dietary consumption patterns? Results from the Choose Healthy Options Consciously Everyday (CHOICE) randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, V.; Davy, B.M.; Duffey, K.J. Is beverage consumption related to specific dietary patterns? Curr. Nutr. Res. 2015, 4, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffey, K.J.; Steffen, L.M.; Van Horn, L.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Popkin, B.M. Dietary patterns matter: Diet beverages and cardiometabolic risks in the longitudinal Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffey, K.J.; Popkin, B.M. Adults with healthier dietary patterns have healthier beverage patterns. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2901–2907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Willett, W. Nutritional Epidemiology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

| Beverage Groups (oz) | Age Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–29 | 30–49 | 50–65 | 66+ | |

| Mean (SE), oz | ||||

| Water | 41 (1.4) | 40.8 (0.9) | 35 (1.3) | 26 (0.7) |

| Coffee & Tea | 5 (0.5) | 12.3 (0.5) | 20 (0.9) | 18 (0.6) |

| Low Fat Milk | 2 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Diet beverages | 3 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.4) | 7 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) |

| Fruit Juice | 3 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Wine | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Beer | 7 (0.6) | 6.5 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) | 2 (0.2) |

| Liquor | 1 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.03) |

| Whole Fat Milk | 3 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) | 19 (0.8) | 14.1 (0.6) | 8 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) |

| Energy (kcal) | ||||

| Total kcal from beverages | 506 (12) | 463 (10) | 371 (12) | 253 (6) |

| % kcal from beverages | 21 (0.4) | 20 (0.03) | 18 (0.03) | 15 (0.03) |

| Total kcal | 1831 (25) | 1820 (19) | 1706 (17) | 1479 (14) |

| Nutrients (% of energy) | ||||

| Total Fat | 32 (0.2) | 33 (0.2) | 34 (0.2) | 34 (0.2) |

| Saturated Fat | 11 (0.1) | 11 (0.01) | 11 (0.1) | 11 (0.01) |

| Total Sugar | 22 (0.2) | 21 (0.2) | 20 (0.2) | 21 (0.1) |

| Mean (SE a) SSB b, oz c | Percent Consumers by SSB Servings, % (SE) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sample Size | Full Sample | Among Consumers | Non-Consumers | 1 | >1–2 | >2 |

| 19–29 | 3123 | 18.5 (0.8) | 29.6 (0.9) | 37.4 (1.5) | 4.3 (0.5) | 16.4 (0.9) | 41.8 (1.6) |

| 30–49 | 5411 | 14.1 (0.6) | 27.2 (0.7) | 48.3 (1.3) | 4.6 (0.4) | 14.4 (0.8) | 32.7 (1.2) |

| 50–65 | 4329 | 7.6 (0.3) | 20.8 (0.6) | 63.4 (1.2) | 4.4 (0.4) | 13.3 (0.8) | 18.9 (1.1) |

| 66+ | 3566 | 4.3 (0.2) | 14.7 (0.5) | 71.1 (0.9) | 7.4 (0.6) | 12.1 (0.8) | 8.5 (0.5) |

| 19+ | 16,429 | 11.7 (0.3) | 25.3 (0.5) | 53.7 (0.9) | 4.9 (0.3) | 14.3 (0.5) | 27.1 (0.7) |

| SSB a,b Consumers, by Servings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 1 | >1–2 | >2 |

| 2544 | 4181 | 6081 | |

| Total Energy from Beverages | |||

| Reported intake | 323 (14) | 401 (9) | 682 (9) |

| With water replacement | 223 (14) | 301 (9) | 582 (9) |

| Percent change | −33.1 | −20.2 | −14.2 |

| Percent energy from beverages | |||

| Reported intake | 17 (0.6) | 20 (0.3) | 27 (0.4) |

| With water replacement | 11 (0.7) | 15 (0.3) | 24 (0.4) |

| SSB Consumers, Mean (SE c) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Full Sample | Non-Consumers | 1 Serving | >1–2 Servings | >2 Servings |

| 19–29 | 66.2 (0.6) | 81.0 (0.7) d | 69.7 (1.5) e | 60.3 (0.9) f | 54.9 (0.6) g |

| 30–49 | 68.7 (0.4) | 80.0 (0.4) d | 68.7 (1.5) e | 61.4 (0.5) f | 55.2 (0.4) g |

| 50–65 | 71.3 (0.3) | 78.9 (0.3) d | 68.2 (1.5) e | 60.2 (0.7) f | 54.5 (0.5) g |

| 66+ | 73.5 (0.3) | 79.3 (0.4) d | 66.7 (1.3) e | 58.6 (0.6) f | 54.4 (0.7) g |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duffey, K.J.; Poti, J. Modeling the Effect of Replacing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption with Water on Energy Intake, HBI Score, and Obesity Prevalence. Nutrients 2016, 8, 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8070395

Duffey KJ, Poti J. Modeling the Effect of Replacing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption with Water on Energy Intake, HBI Score, and Obesity Prevalence. Nutrients. 2016; 8(7):395. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8070395

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuffey, Kiyah J., and Jennifer Poti. 2016. "Modeling the Effect of Replacing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption with Water on Energy Intake, HBI Score, and Obesity Prevalence" Nutrients 8, no. 7: 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8070395

APA StyleDuffey, K. J., & Poti, J. (2016). Modeling the Effect of Replacing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption with Water on Energy Intake, HBI Score, and Obesity Prevalence. Nutrients, 8(7), 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8070395