Magnesium Levels in Drinking Water and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

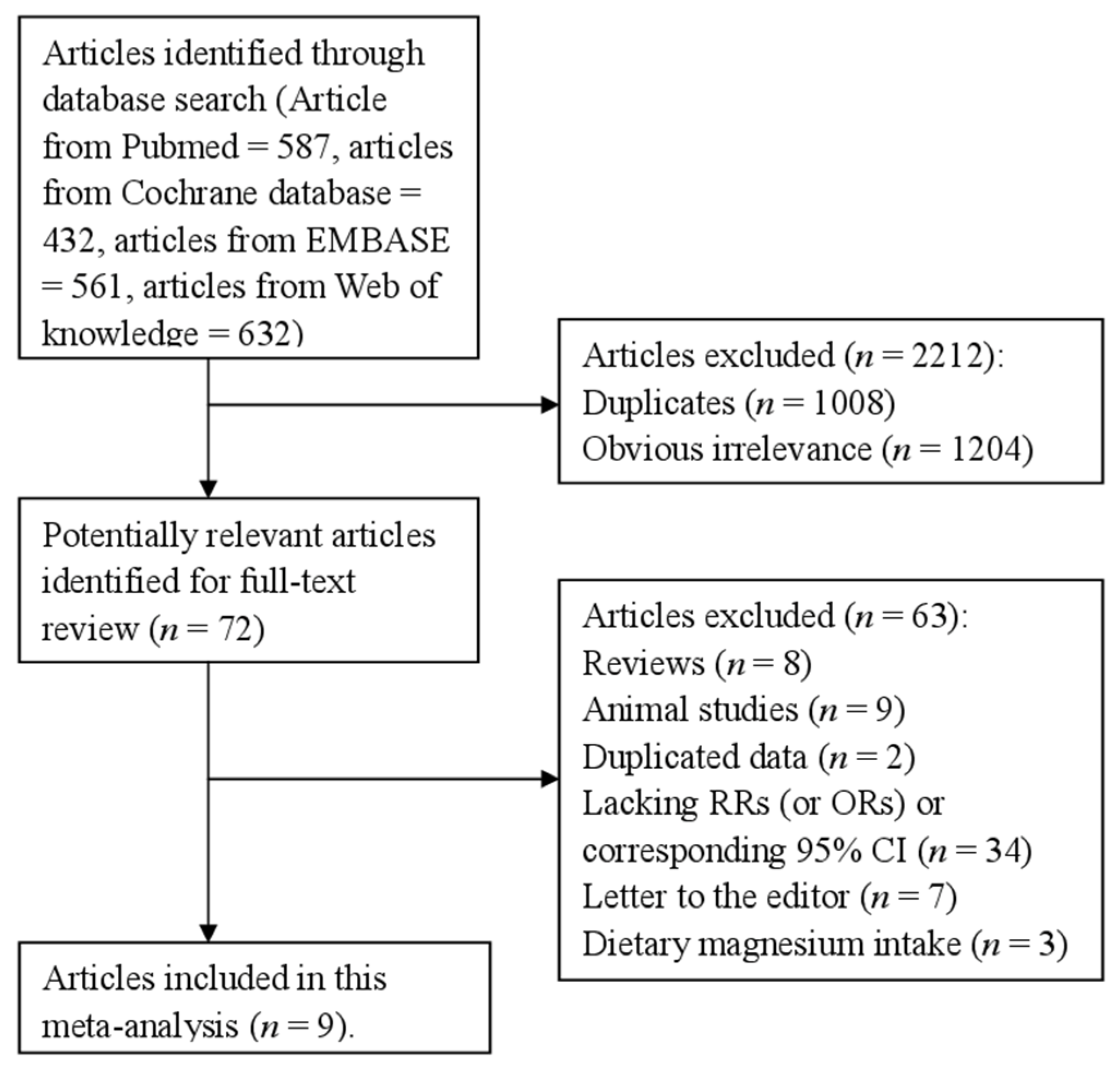

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategies

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

| Study Year | Country | Study Design | Participants (Cases) | Age (Years) | CHD Outcome | Category (mg/L) | RR (95% CI) for Highest Versus Lowest Category | Adjustment for Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leurs et al. 2010 | Netherlands | Prospective study | 33,258 (1642) | 55–69 | IHD | Male 1.7–3.8 4.2–6.0 6.0–8.0 8.0–8.2 8.5–26.2 Female 1.7–3.8 4.2–6.0 6.0–8.0 8.0–8.2 8.5–26.2 | Male 1 1.04(0.76–1.42) 1.21(0.87–1.71) 0.95(0.67–1.33) 1.23(0.82–1.86) Female 1 1.08(0.73–1.58) 0.75(0.49–1.18) 0.97(0.62–1.53) 0.89(0.50–1.59) | Adjusted for Age, current smoking, number of cigarettes smoked, years of active smoking, diabetes, hypertension, BMI, dietary calcium, dietary magnesium, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, fruit and vegetable consumption, alcohol consumption, total energy intake (kilocalories), physical activity, educational level, volume of water consumption, magnesium or calcium concentration in tap water (depending on the exposure variable), use of diuretics, and use of multivitamins with minerals or calcium supplementation |

| Luoma et al. 1983 | Finland | Case-control study | 100 (50) | 30–64 | MI | Highest vs. lowest | 1.63(0.62–4.52) | Adjusted for age and municipality with the cases. |

| Maheswaran et al. 1999 | England | Case-control study | 2,496,659 (64,226) | ≥45 | IHD | Highest vs. lowest | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | Adjusted for Age, sex, Carstairs deprivation quintile and geographical gradients. |

| Punsar et al. 1979 | Finland | Prospective study | 1711 (198) | 40–59 | CHD | Highest vs. lowest | 0.64(0.44–0.91) | Na. |

| Rosenlund et al. 2005 | Sweden | Case-control study | 458 (116) | 45–70 | IHD | 0.20–0.9 0.9–1.9 1.9–3.5 3.5–19.2 | 1 1.07(0.73–1.55) 0.86(0.59–1.26) 0.97 (0.66–1.41) | Adjusted for Age, sex, catchment area, smoking, hypertension, socioeconomy, job strain, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, and physical inactivity. |

| Rubenowitz et al. 1996 | Sweden | Case-control study | 1843 (854) | 50–69 | IHD | ≤3.5 3.6–6.8 6.9–9.7 ≥9.8 | 1 0.88(0.66–1.16) 0.70(0.53–0.93) 0.65(0.50–0.84) | Adjusted for Age and magnesium and calcium, respectively. |

| Rubenowitz et al. 1999 | Sweden | Case-control study | 1746 (378) | 50–69 | IHD | ≤3.4 3.5–6.7 6.8–9.8 ≥9.9 | 1 1.08(0.78–1.49) 0.93(0.64–1.34) 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | Adjusted for Age and magnesium and calcium, respectively. |

| Rubenowitz et al. 2000 | Sweden | Case-control study | 521 (263) | 50–74 | IHD | Highest vs. lowest | 0.64 (0.42–0.97) | Adjusted for Age and magnesium and calcium, respectively. |

| Yang et al. 2006 | China | Case-control study | 20,188 (10,094) | 50–69 | IHD | ≤7.7 7.8–13.5 14.1–41.3 | 1 1.00(0.93–1.08) 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | Adjusted for Age, sex, urbanization level of residence, and magnesium and calcium levels in drinking water respectively. |

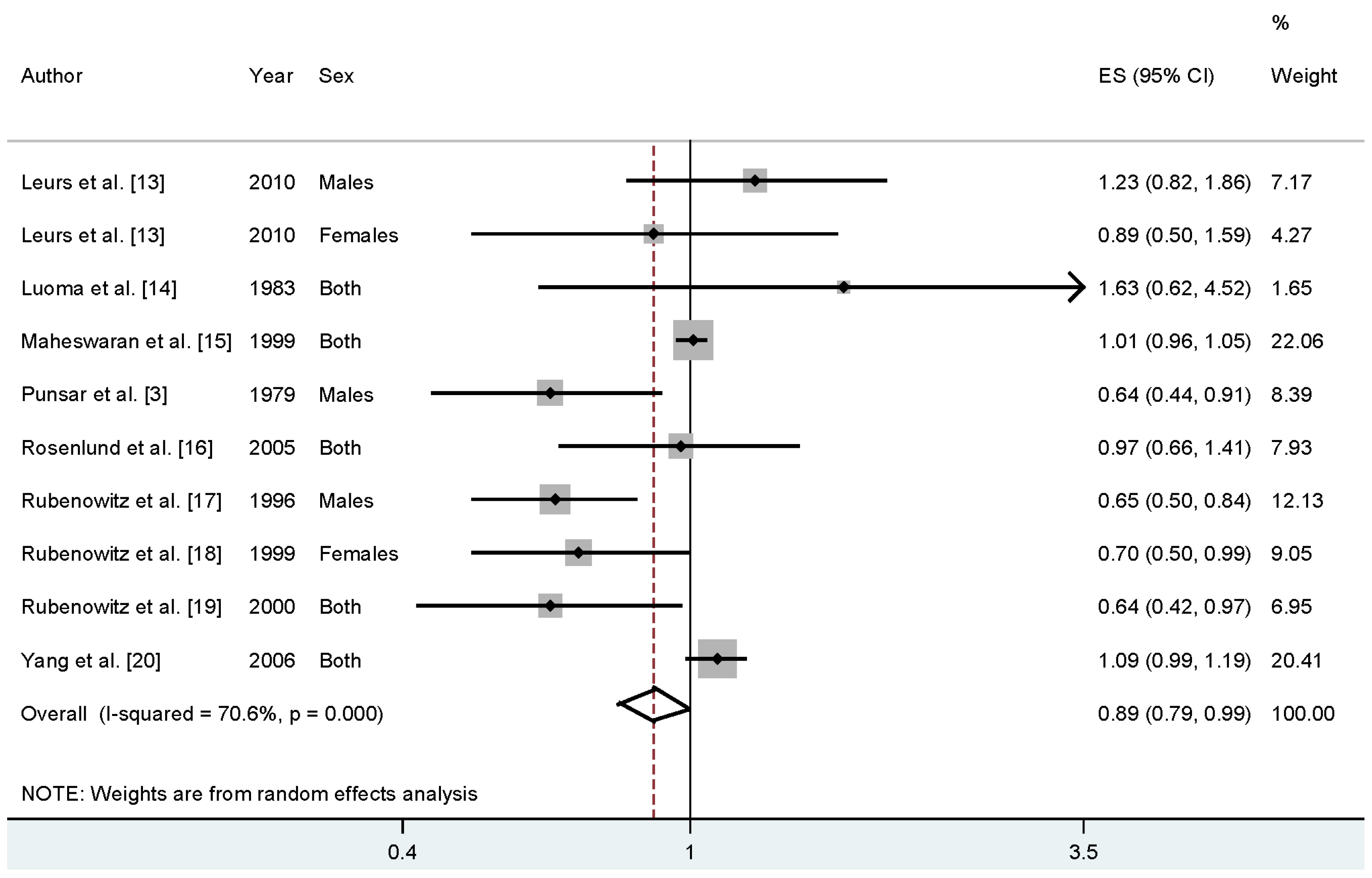

3.2. High versus Low Analyses

3.3. Meta-Regression and Subgroup Analysis

| Subgroups | No. | No. | RR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Studies | I2 (%) | p-Value | ||

| All studies | 77,821 | 10 | 0.89 (0.79–0.99) | 70.6 | 0.000 |

| Study design | |||||

| Cohort | 1840 | 3 | 0.88 (0.57–1.34) | 63.5 | 0.064 |

| Case-control | 75,981 | 7 | 0.87 (0.76–0.98) | 74.6 | 0.001 |

| Geographic locations | |||||

| Europe | 67,727 | 9 | 0.83 (0.69–0.98) | 70.0 | 0.001 |

| Asia | 10,094 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| CHD outcome | |||||

| IHD | 65,868 | 3 | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | 0.0 | 0.586 |

| MI | 11,755 | 6 | 0.81 (0.64–0.98) | 78.6 | 0.000 |

| CHD | 198 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Sex | |||||

| Males | 2194 | 3 | 0.78 (0.54–1.15) | 73.3 | 0.024 |

| Females | 878 | 2 | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.0 | 0.484 |

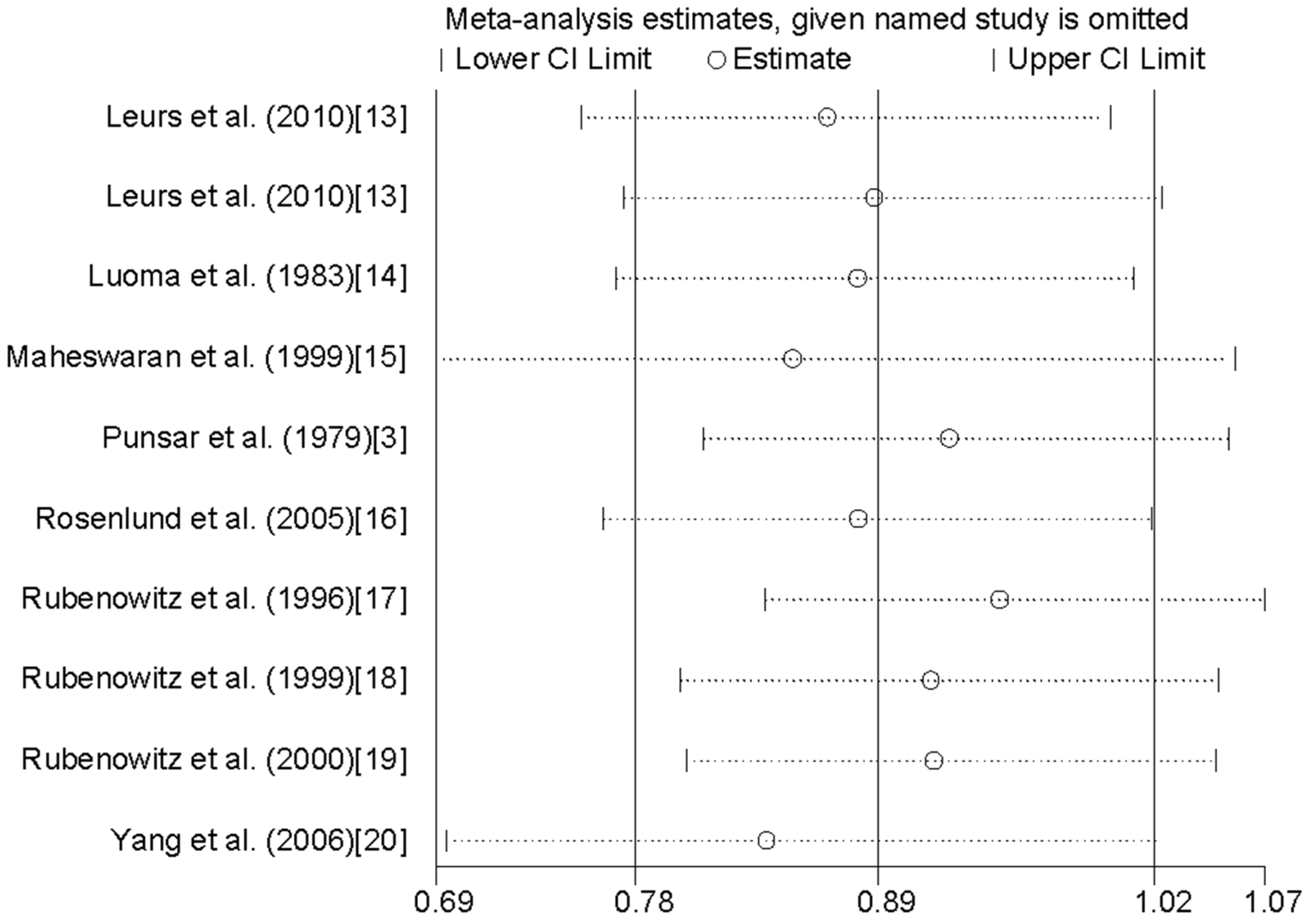

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis and Small Study Effect

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Lopez, A.D. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997, 349, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punsar, S.; Karvonen, M.J. Drinking water quality and sudden death: Observations from West and East Finland. Cardiology 1979, 64, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, D. Mortality and water hardness. Lancet 1975, 1, 398–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan, P.; Preziosi, P.; Durlach, V.; Valeix, P.; Ribas, L.; Bouzid, D.; Favier, A.; Hercberg, S. Dietary magnesium intake in a French adult population. Magnes. Res. 1997, 10, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Turlapaty, P.D.; Altura, B.M. Magnesium deficiency produces spasms of coronary arteries: Relationship to etiology of sudden death ischemic heart disease. Science 1980, 208, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipperfield, B.; Chipperfield, J.R. Heart-muscle magnesium, potassium, and zinc concentrations after sudden death from heart-disease. Lancet 1973, 2, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br. Méd. J. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat. Méd. 2004, 23, 1663–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Méd. J. 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, A. Assessing the influence of a single study in the meta-analysis estimate. Stata Tech. Bull. 1999, 47, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Leurs, L.J.; Schouten, L.J.; Mons, M.N.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. Relationship between tap water hardness, magnesium, and calcium concentration and mortality due to ischemic heart disease or stroke in The Netherlands. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, H.; Aromaa, A.; Helminen, S.; Murtomaa, H.; Kiviluoto, L.; Punsar, S.; Knekt, P. Risk of myocardial infarction in Finnish men in relation to fluoride, magnesium and calcium concentration in drinking water. Acta Méd. Scand. 1983, 213, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheswaran, R.; Morris, S.; Falconer, S.; Grossinho, A.; Perry, I.; Wakefield, J.; Elliott, P. Magnesium in drinking water supplies and mortality from acute myocardial infarction in north west England. Heart 1999, 82, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenlund, M.; Berglind, N.; Hallqvist, J.; Bellander, T.; Bluhm, G. Daily intake of magnesium and calcium from drinking water in relation to myocardial infarction. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rubenowitz, E.; Axelsson, G.; Rylander, R. Magnesium in drinking water and death from acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 143, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenowitz, E.; Axelsson, G.; Rylander, R. Magnesium and calcium in drinking water and death from acute myocardial infarction in women. Epidemiology 1999, 10, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenowitz, E.; Molin, I.; Axelsson, G.; Rylander, R. Magnesium in drinking water in relation to morbidity and mortality from acute myocardial infarction. Epidemiology 2000, 11, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Tsai, S.S.; Chiu, H.F. Calcium and magnesium in drinking water and risk of death from acute myocardial infarction in Taiwan. Environ. Res. 2006, 101, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munafo, M.R.; Flint, J. Meta-analysis of genetic association studies. TRENDS Genet. 2004, 20, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; He, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Qin, G.; Tan, N. Magnesium Levels in Drinking Water and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010005

Jiang L, He P, Chen J, Liu Y, Liu D, Qin G, Tan N. Magnesium Levels in Drinking Water and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2016; 8(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Lei, Pengcheng He, Jiyan Chen, Yong Liu, Dehui Liu, Genggeng Qin, and Ning Tan. 2016. "Magnesium Levels in Drinking Water and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 8, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010005

APA StyleJiang, L., He, P., Chen, J., Liu, Y., Liu, D., Qin, G., & Tan, N. (2016). Magnesium Levels in Drinking Water and Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010005