The Economic Impact of Lower Protein Infant Formula for the Children of Overweight and Obese Mothers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

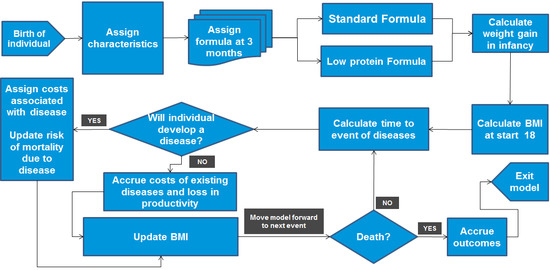

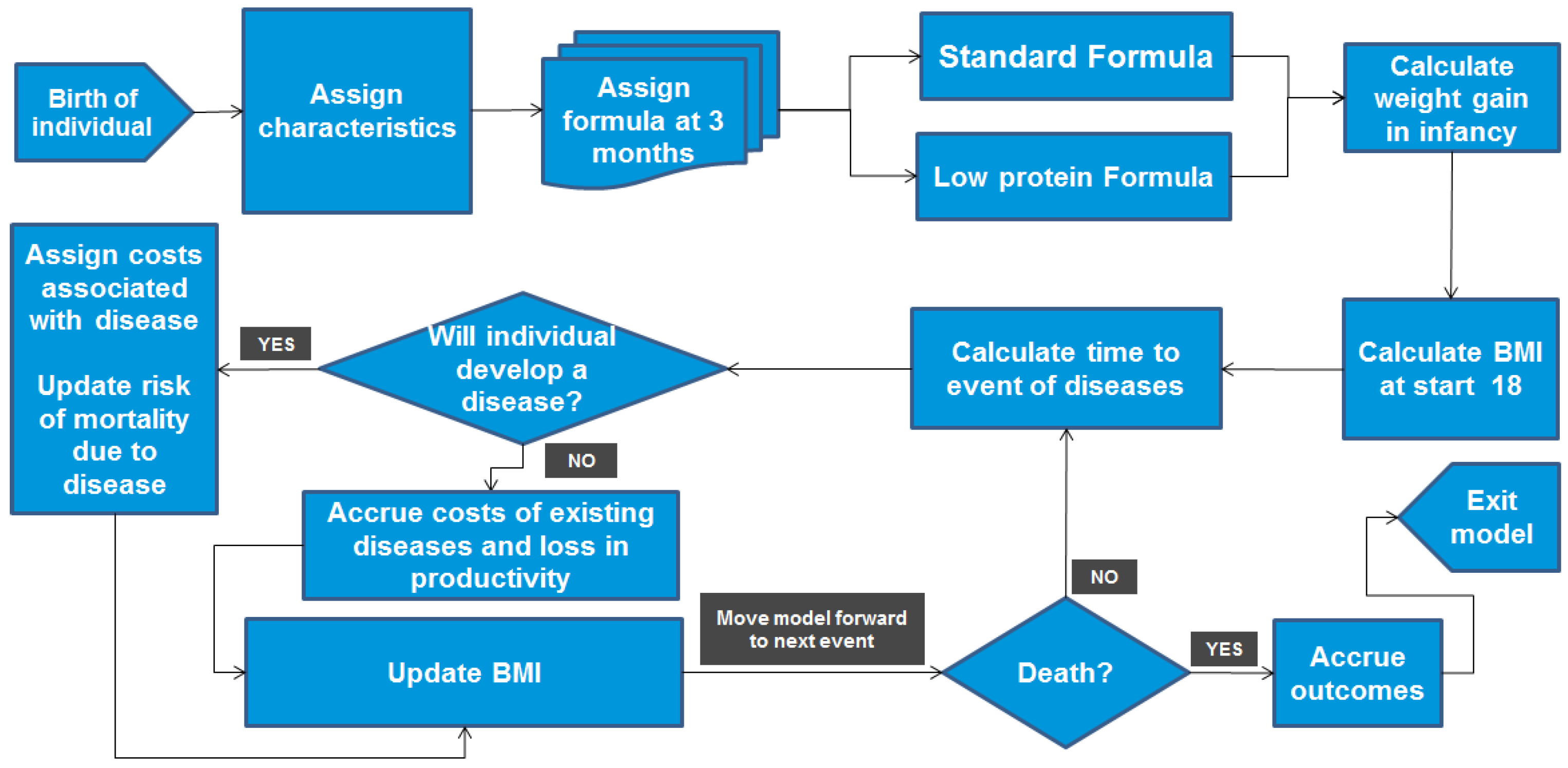

2.1. Modelling Approach

- lpIF, which has low protein content and caloric density (1.65 g/100 kcal, 62.8 kcal/dL) and also contains probiotics.

- A currently-used formula with high protein content and caloric density (2.63 g/100 kcal, 65.6 kcal/dL).

2.2. Model Inputs

| Parameter | Mean Value | Standard Error | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of new-borns (% male) | 52.0% | - | [24] |

| Mean birth weight in Mexico (in grams) | 3 202 | 472 | |

| Mean birth height * in Mexico (in cm) | 50.3 | 2.7 | |

| Mean mother BMI in Mexico (kg/m2) | 26.2 | 4.2 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.1 | 1.7 | |

| Mean mother height (in cm) | 155.4 | 5.7 | |

| Head circumference (in cm) | 34.3 | 1.8 | |

| Maternal socioeconomic status (medium to low) ** | 59.5% | - | |

| % of mothers smoking *** | 10.70% | - | |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 87.6% | 32.3% **** | [13] |

| Race (% Hispanic non-white) | 12.4% | - | |

| Education (<4 years) | 0.9% | - | |

| Education (4 to 8 years) | 6.6% | - | |

| Education (8 to 9 years) | 10.7% | - | |

| Education (≥10 years) | 81.8% | - | |

| Family diabetes history (parent or sibling had diabetes) | 29.5% | 1.5% ***** | [25] |

| Cholesterol/HDL-C ratio | Age and gender specific; see Table S22. | ||

| Fasting glucose level (mg/dL) | |||

| SBP level (mm Hg) | |||

| HDL level (mg/dL) | |||

| Smoking status | |||

2.3. BMI Trajectory

2.3.1. BMI at Age 2 Years

2.3.2. BMI at Age 17 Years

| Parameter | Mean | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 10.779 | 4.356 |

| Weight gain in infancy at 24 months | 1.788 ** | 0.171 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 1.761 | 0.426 |

| Gender status (Female) | 1.089 | 0.325 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 0.106 | 0.114 |

| Maternal low-medium socioeconomic status | −0.201 | 0.171 |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | 0 | 0.042 |

2.3.3. BMI at Age 18 Years and Higher

2.4. Disease Risks

2.4.1. Primary Events

2.4.2. Secondary Events

2.5. Mortality

2.6. Healthcare Costs

2.7. Health-Related Quality-of-Life Impacts

2.8. Productivity Loss

3. Results

3.1. Base-Case Results

3.1.1. Clinical Outcomes

| Clinical Outcomes | lpIF | Currently Used Formula | Absolute Difference | Relative Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average BMI (kg/m2) outcomes estimated by the lpIF model per individual over time (undiscounted) | ||||

| Average BMI at 18 years old | 24.8 | 25.8 | −1.0 | −3.9% |

| Average BMI at 30 years old | 26.6 | 27.7 | −1.1 | −4.1% |

| Average BMI at 45 years old | 28.1 | 29.0 | −1.0 | −3.4% |

| Average BMI at 60 years old | 29.2 | 30.1 | −0.9 | −3.0% |

| Average lifetime BMI | 27.3 | 28.2 | −1.0 | −3.5% |

| % of population becoming obese (BMI ≥ 30) | 15.5% | 17.1% | −1.6% | −10.5% |

| Years in obese state | 2.4 | 2.6 | −0.2 | −8.1% |

| Probability of experiencing clinical events | ||||

| Diabetes | 14.4% | 14.8% | −0.4% | −2.9% |

| Angina | 8.3% | 8.6% | −0.3% | −3.3% |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.2% | 3.3% | −0.1% | −2.2% |

| Stroke | 0.267% | 0.274% | −0.007% | −2.9% |

3.1.2. Economic Outcomes

| Economic Outcomes | lpIF | Currently Used Formula | Absolute Difference | Relative Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRQL (discounted) | ||||

| Life years | 26.098 | 26.097 | 0.001 | 0.002% |

| QALYs | 24.76 | 24.75 | 0.01 | 0.05% |

| Direct health costs per person (2014 MXN, discounted) | ||||

| Diabetes | 4394 | 4569 | −175 | −4.0% |

| Angina | 721 | 751 | −30 | −4.2% |

| Myocardial infarction | 32 | 34 | −1 | −3.4% |

| Stroke | 1568 | 1622 | −54 | −3.5% |

| Total | 6715 | 6975 | −260 | −3.9% |

3.1.3. Sensitivity Analyses

3.2. Scenario Analyses

| Scenario | Costs Absolute Difference, 2014 MXN (lpIF vs. Currently-Used Formula) | Costs Relative Difference (lpIF vs. Currently-Used Formula) |

|---|---|---|

| Base case | −984 | −4.05% |

| Undiscounted outcomes | −7241 | −3.95% |

| Individual characteristics based on the lpIF Chilean trial population | −1034 | −4.36% |

| Trial data used to observe impact over 12 months | −265 | −1.04% |

| Valuing productivity losses using the friction approach | −1456 | −1.25% |

| Ekelund equations at age 17 without the adjustment factor | −657 | −2.79% |

3.3. Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Factsheet No. 311. 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- World Health Organization. What Are the Health Consequences of Being Overweight? Online Q&A. 2013. Available online: http://www.who.int/features/qa/49/en/ (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight, Facts. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/media/en/gsfs_obesity.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2015).

- Messiah, S.E.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Natale, R.A.; Miller, T.L. The imperative to prevent and treat childhood obesity: Why the world cannot afford to wait. Clin. Obes. 2013, 3, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health: Childhood Obesity and Overweight. 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/ (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- Singh, A.S.; Mulder, C.; Twisk, J.W.; van Mechelen, W.; Chinapaw, M.J. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, J.; Fisher, D.; Lucas, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Roberts, H.; Law, C. Being big or growing fast: Systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 2005, 331, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druet, C.; Stettler, N.; Sharp, S.; Simmons, R.K.; Cooper, C.; Smith, G.D.; Ekelund, U.; Lévy-Marchal, C.; Jarvelin, M.R.; Kuh, D.; et al. Prediction of childhood obesity by infancy weight gain: An individual-level meta-analysis. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerwagen, M.J.; Miller, M.R.; Barbour, L.A.; Friedman, J.E. Maternal obesity and fetal metabolic programming: A fertile epigenetic soil. Am. J. Physiol. 2010, 299, R711–R722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tounian, P. Programming towards childhood obesity. Ann. Nutr. Metabol. 2011, 58 (Suppl. 2), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillycrop, K.A.; Burdge, G.C. Epigenetic changes in early life and future risk of obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karachaliou, M.; Georgiou, V.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Chalkiadaki, G.; Daraki, V.; Koinaki, S.; Dermitzaki, E.; Sarri, K.; Vassilaki, M.; Kogevinas, M.; et al. Association of trimester-specific gestational weight gain with fetal growth, offspring obesity, and cardiometabolic traits in early childhood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inostroza, J.; Haschke, F.; Steenhout, P.; Grathwohl, D.; Nelson, S.E.; Ziegler, E.E. Low-Protein Formula Slows Weight Gain in Infants of Overweight Mothers. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 59, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koletzko, B.; von Kries, R.; Monasterolo, R.C.; Escribano, J.; Scaglioni, S.; Giovannini, M.; Beyer, J.; Demmelmair, H.; Anton, B.; Gruszfeld, D.; et al. Can infant feeding choices modulate later obesity risk? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1502S–1508S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haschke, F.; Grathwohl, D.; Haiden, N. Metabolic Programming: Effects of Early Nutrition on Growth, Metabolism, and Body Composition. In Preventive Aspects of Early Nutrition, Proceedings of 85th Nestlé Nutrition Institute (NNI) Workshop, Windsor, United Kingdom, 24–26 May 2015; Fewtrell, M., Haschke, F., Prescott, S., Eds.; Nestlé Nutrition Institute: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haschke, F.; Grathwohl, D.; Detzel, P.; Steenhout, P.; Wagemans, N. Postnatal High Protein Intake Can Contribute to Accelerated Weight Gain of Infants and Increased Obesity Risk. In Metabolic Programming: Effects of Early Nutrition on Growth, Metabolism, and Body Composition, Proceedings of 86th Nestlé Nutrition Institute (NNI) Workshop, Beijing, China, 17–19 November 2015; Fewtrell, M., Haschke, F., Prescott, S., Eds.; Nestlé Nutrition Institute: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koletzko, B.; von Kries, R.; Closa, R.; Escribano, J.; Scaglioni, S.; Giovannini, M.; Beyer, J.; Demmelmair, H.; Gruszfeld, D.; Dobrzanska, A.; et al. Lower protein in infant formula is associated with lower weight up to age 2 y: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, E.E.; Fields, D.A.; Chemausek, S.D.; Philippe, S.; Grathwohl, D.; Jeter, J.M.; Nelson, S.E.; Haschke, F. Effect of infant formula with protein content of 1.6 g/100 kcal fed between 3–12 months on growth at 3 and 5 years of age. J. Dev. Origins Health Dis. 2015, 61, 593. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.; Grote, V.; Closa-Monasterolo, R.; Escribano, J.; Langhendries, J.P.; Dain, E.; Giovannini, M.; Verduci, E.; Gruszfeld, D.; Socha, P.; et al. Lower protein content in infant formula reduces BMI and obesity risk at school age: follow-up of a randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Obesity Update. 2014. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Obesity-Update-2014.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- De Cossío, T.G.; Escobar-Zaragoza, L.; González-Castell, D.; Reyes-Vázquez, H.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A. Breastfeeding in Mexico was stable, on average, but deteriorated among the poor, whereas complementary feeding improved: Results from the 1999 to 2006 National Health and Nutrition Surveys. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, M.C.; O’Brien, B.; Hornberger, J.; Jackson, J.; Johannesson, M.; McCabe, C.; Luce, B.R.; ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices—Modeling Studies. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in healthcare evaluation: Report of the ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices—Modeling Studies. Value Health 2003, 6, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, J.J. Pharmacoeconomic analyses using discrete event simulation. PharmacoEconomics 2005, 23, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Stein, A.D.; Parra-Cabrera, S.; Wang, M.; Imhoff-Kunsch, B.; Juárez-Márquez, S.; Rivera, J.; Martorell, R. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy on gestational age and size at birth: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Mexico. Food Nutr. Bull. 2010, 31 (Suppl. 2), S108–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondragon, H.; Charlton, R.W.; Peart, T.; Burguete-Garcia, A.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Hsueh, W. Diabetes Risk Assessment in Mexicans and Mexican Americans: Effects of parental history of diabetes are modified by adiposity level. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2260–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, E.; de Leon, C.F.M.; Miller, G.E. Applying mixed regression models to the analysis of repeated-measures data in psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom. Med. 2006, 68, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlin, A.; Rössner, S. Maternal body weight development after pregnancy. Int. J. Obes. 1990, 14, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rössner, S.; Öhlin, A. Maternal body weight and relation to birth weight. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1990, 69, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, K.; Davies, R.; Roderick, P.; Chase, D.; Raftery, J. The development of a simulation model of the treatment of coronary heart disease. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2002, 5, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekelund, U.; Ong, K.; Linne, Y.; Neovius, M.; Brage, S.; Dunger, D.B.; Wareham, N.J.; Rössner, S. Upward weight percentile crossing in infancy and early childhood independently predicts fat mass in young adults: The Stockholm Weight Development Study (SWEDES). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Østbye, T.; Malhotra, R.; Landerman, L.R. Body mass trajectories through adulthood: Results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Cohort (1981–2006). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Infobase. Non-Communicable Diseases Indicators. Available online: https://apps.who.int/infobase/Indicators.aspx (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- Stern, M.P.; Williams, K.; Haffner, S.M. Identification of persons at high risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Do we need the oral glucose tolerance test? Ann. Internal Med. 2002, 136, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.; Bozeman, S.R.; Burton, T.M.; Hoaglin, D.C.; Ben-Joseph, R.; Pashos, C.L. Prediction of first events of coronary heart disease and stroke with consideration of adiposity. Circulation 2008, 118, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, R.B.; Russell, M.W.; Huse, D.M.; Ellison, R.C.; Silbershatz, H.; Wilson, P.W.; Hartz, S.C. Primary and subsequent coronary risk appraisal: New results from the Framingham study. Am. Heart J. 2000, 139, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, H.-C.; Bogousslavsky, J.; Brass, L.M.; Cimminiello, C.; Csiba, L.; Kaste, M.; Leys, D.; Matias-Guiu, J.; Rupprecht, H.J.; MATCH Investigators. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 364, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Manson, J.E.; Gaziano, J.M.; Buring, J.E.; Hennekens, C.H. Low-dose aspirin therapy for chronic stable angina: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann. Internal Med. 1991, 114, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirica, B.M.; Bonaca, M.P.; Braunwald, E.; de Ferrari, G.M.; Isaza, D.; Lewis, B.S.; Mehrhof, F.; Merlini, P.A.; Murphy, S.A.; Sabatine, M.S.; et al. Vorapaxar for secondary prevention of thrombotic events for patients with previous myocardial infarction: A prespecified subgroup analysis of the TRA 2 P-TIMI 50 trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueman, P.; Lowson, K.; Bending, M.; Ganderton, M.; Chaplin, S.; Wright, D.; Duffy, S.; Saxby, R. Bowel Cancer Services: Costs and Benefits. Final Report to the Department of Health 2007. Available online: http://www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.44050!/file/FinalBowelCancerReport—Apr07.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Human Life-Table Database: Continuous Life Tables from Mexico. 1985. Available online: http://www.lifetable.de/cgi-bin/Country.plx?Country=Mexico (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Segmented Life Tables for Mexico. 2011. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gho/athena/data/GHO/LIFE_0000000029,LIFE_0000000030,LIFE_0000000031,LIFE_0000000032,LIFE_0000000033,LIFE_0000000034,LIFE_0000000035?filter=COUNTRY:NGA&format=xml&profile=excel (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. National Consumer Price Index and its Components. 2014. Available online: http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/IndicePrecios/Cuadro.aspx?nc=CA55&T=%C3%8Dndices (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal. 2013. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/resources/non-guidance-guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- Ziegler, E.E.; Fields, D.A.; Chernausek, S.D.; Steenhout, P.; Grathwohl, D.; Jeter, J.M.; Nelson, S.E.; Haschke, F. Adequacy of Infant Formula With Protein Content of 1.6 g/100 kcal for Infants between 3 and 12 months. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 61, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trueman, P.; Haynes, S.; Felicity Lyons, G.; Louise McCombie, E.; McQuigg, M.S.; Mongia, S.; Noble, P.A.; Quinn, M.F.; Ross, H.M.; Thompson, F.; et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of weight management in primary care. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weng, S.F.; Redsell, S.A.; Swift, J.A.; Yang, M.; Glazebrook, C.P. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbins, M.; Decorby, K.; Choi, B.C.K. The association between obesity and cancer risk: A meta-analysis of observational studies from 1985 to 2011. ISRN Prevent. Med. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Shi, C.; Zou, Y.; Qin, H. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marsh, K.; Möller, J.; Basarir, H.; Orfanos, P.; Detzel, P. The Economic Impact of Lower Protein Infant Formula for the Children of Overweight and Obese Mothers. Nutrients 2016, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010018

Marsh K, Möller J, Basarir H, Orfanos P, Detzel P. The Economic Impact of Lower Protein Infant Formula for the Children of Overweight and Obese Mothers. Nutrients. 2016; 8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarsh, Kevin, Jörgen Möller, Hasan Basarir, Panagiotis Orfanos, and Patrick Detzel. 2016. "The Economic Impact of Lower Protein Infant Formula for the Children of Overweight and Obese Mothers" Nutrients 8, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010018

APA StyleMarsh, K., Möller, J., Basarir, H., Orfanos, P., & Detzel, P. (2016). The Economic Impact of Lower Protein Infant Formula for the Children of Overweight and Obese Mothers. Nutrients, 8(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010018