An Evaluation of the Effects of the Australian Food and Health Dialogue Targets on the Sodium Content of Bread, Breakfast Cereals and Processed Meats

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Product Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. FHD Targets and Food Company Commitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Products and Food Companies Identified

| (A) Bread | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

FHD target: maximum sodium 400 mg/100 g. Set in May, 2010, deadline to meet due by December, 2013. | ||||

| FHD participants total products n (%) | 145 (84%) | 135 (63%) | 146 (63%) | 177 (66%) |

| ALDI | 25 | 20 | 18 | 22 |

| Coles | 14 | 18 | 18 | 37 |

| George Weston | 45 | 36 | 41 | 46 |

| Goodman Fielder | 48 | 52 | 54 | 52 |

| Woolworths | 13 | 9 | 15 | 20 |

| FHD non-participants total products n (%) | 27 (16%) | 79 (37%) | 86 (37%) | 90 (34%) |

| (B) Bacon/ham/cured meat | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

FHD target: maximum sodium 1090 mg/100 g. Set in January, 2011, deadline to meet due by December, 2013. | ||||

| FHD participants total products n (%) | 83 (92%) | 89 (89%) | 81 (94%) | 98 (88%) |

| ALDI | 12 | 10 | 13 | 11 |

| Coles | 10 | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| D’Orsogna | 5 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| George Weston | 12 | 17 | 14 | 17 |

| Primo Smallgoods | 37 | 36 | 27 | 37 |

| Woolworths | 7 | 7 | 10 | 10 |

| FHD non-participants total products n (%) | 7 (8%) | 11 (11%) | 5 (6%) | 13 (12%) |

| (C) Emulsified luncheon meats | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

FHD target: maximum sodium 830 mg/100 g. Set in January, 2011, deadline to meet due by December, 2013. | ||||

| FHD participants total products n (%) | 9 (69%) | 10 (67%) | 5 (83%) | 7 (64%) |

| ALDI | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Coles | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Primo Smallgoods | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Woolworths | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| FHD non-participants total products n (%) | 4 (31%) | 5 (33%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (36%) |

| (D) Breakfast cereals | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

FHD target: 15% less sodium if >400 mg/100 g. Set in May, 2010, and deadline to meet due by December, 2013. | ||||

| FHD participants total products n (%) | 86 (70%) | 75 (69%) | 97 (69%) | 107 (67%) |

| ALDI | 13 | 0 | 21 | 25 |

| Coles | 10 | 10 | 11 | 14 |

| Kellogg | 28 | 33 | 32 | 33 |

| Nestle | 17 | 19 | 19 | 21 |

| Sanitarium | 9 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| Woolworths | 9 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| FHD non-participants total products n (%) | 39 (30%) | 33 (31%) | 43 (31%) | 52 (33%) |

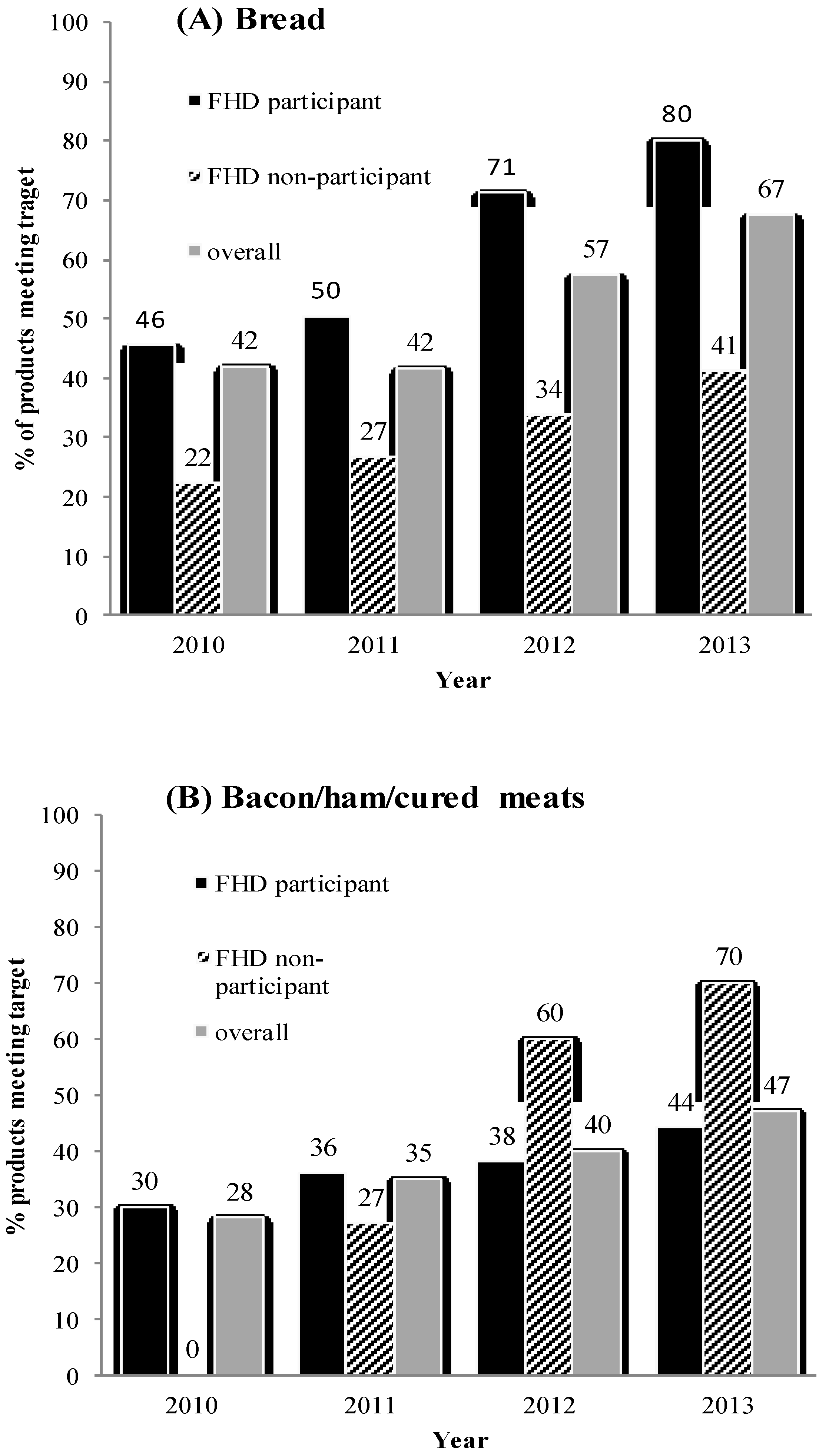

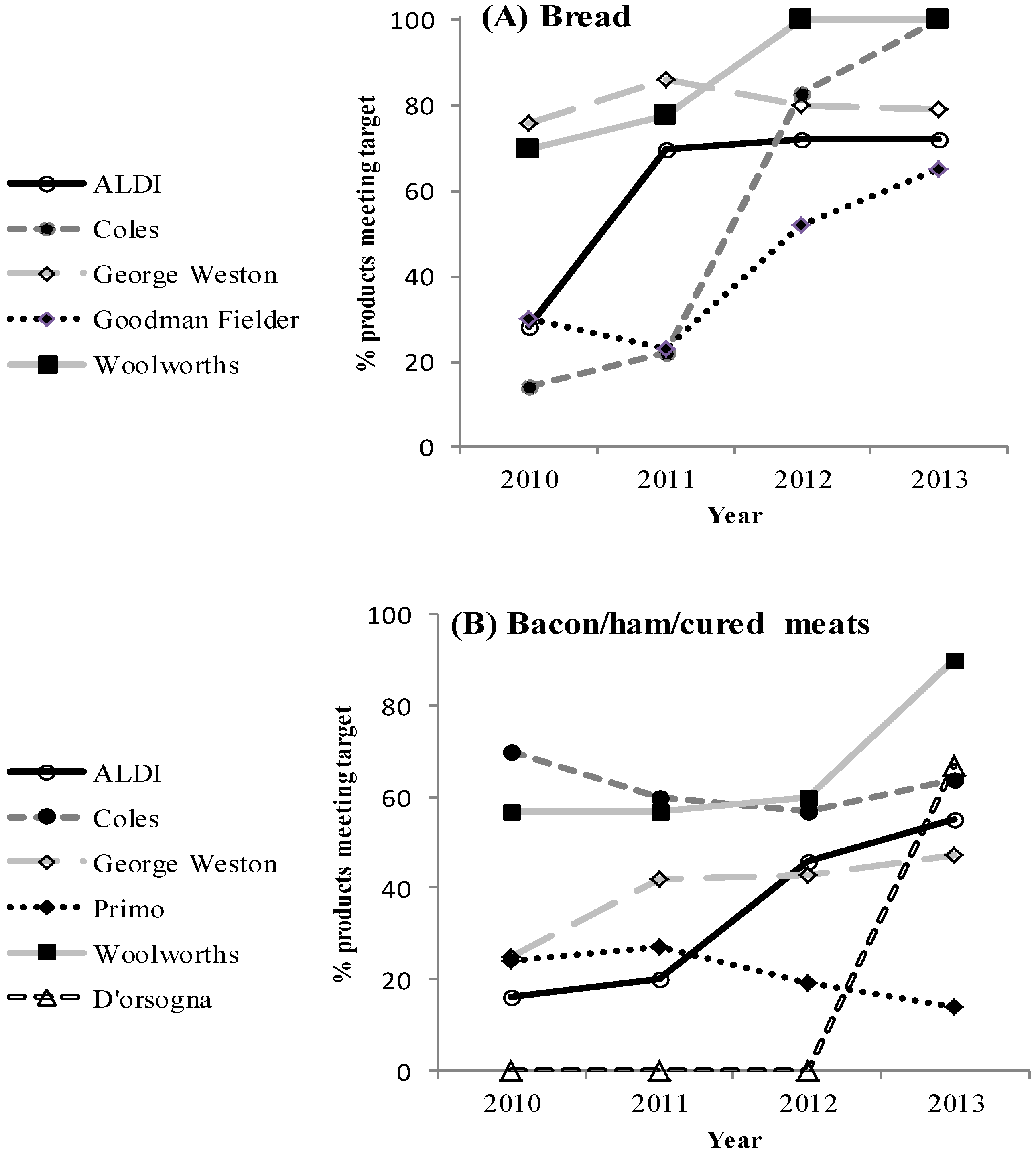

3.2. Proportion of Products Meeting FHD Targets

3.2.1. Breads

3.2.2. Processed Meats

3.2.3. Ready-to-Eat Breakfast Cereals

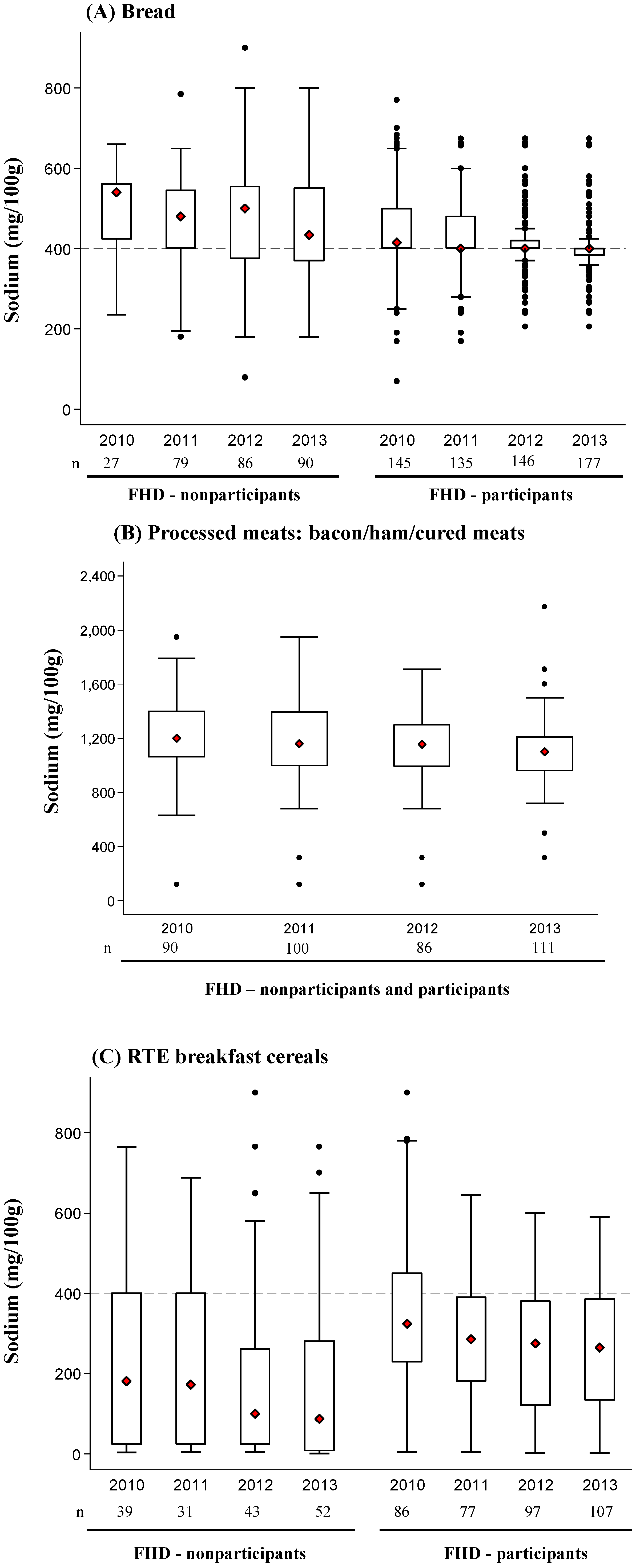

3.3. Change in Mean Sodium Content for Each Product Category over Time

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, F.; MacGregor, G.A. A comprehensive review on salt and health current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum. Hypertens. 2009, 23, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Salt intake and health in the Australian population. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 189, 526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Land, M.-A.; Webster, J.; Christoforou, A.; Praveen, D.; Jeffery, P.; Chalmers, J.; Smith, W.; Woodward, M.; Barzi, F.; Nowson, C. Salt intake assessed by 24 h urinary sodium excretion in a random and opportunistic sample in Australia. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n35.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2014).

- University of Washington; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden Disease Compare 2010. Available online: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (accessed on 9 June 2014).

- Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Chertow, G.M.; Coxson, P.G.; Moran, A.; Lightwood, J.M.; Pletcher, M.J.; Goldman, L. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Spangler, C.M.; Juusola, J.L.; Enns, E.A.; Owens, D.K.; Garber, A.M. Population strategies to decrease sodium intake and the burden of cardiovascular disease a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobiac, L.J.; Vos, T.; Veerman, J.L. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce dietary salt intake. Heart 2010, 96, 1920–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappuccio, F.P.; Capewell, S. How to cut down salt intake in populations. Heart 2010, 96, 1863–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Labarthe, D. The cost-effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce sodium intake. J. Hypertens. 2011, 29, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, I.J.; Tzoulaki, I.; Candeias, V.; Elliott, P. Salt intakes around the world: Implications for public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australia Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results—Foods and Nutrients, 2011–12. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.007~2011-12~Main%20Features~Key%20Findings~1 (accessed on 20 June 2014).

- He, F.J.; Brinsden, H.C.; MacGregor, G.A. UK population salt reduction: An experiment in public health. Lancet 2013, 382 (Suppl. 3), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Survey on Members States’ Implementation of the EU Salt Reduction Framework. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/salt_report1_en.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2014).

- He, F.J.; Brinsden, H.C.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: A successful experiment in public health. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Food and Health Dialogue. Available online: http://www.foodhealthdialogue.gov.au/internet/foodandhealth/publishing.nsf (accessed on 12 June 2014).

- Nenycz-Thiel, M. Private labels in Australia: A case where retailer concentration does not predicate private labels share. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 18, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Composition Database, version 2014; The George Institute for Global Health: Sydney, Australia, 2014.

- Dunford, E.; Webster, J.; Metzler, A.B.; Czernichow, S.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Wolmarans, P.; Snowdon, W.; L’Abbe, M.; Li, N.; Maulik, P.K.; et al. International collaborative project to compare and monitor the nutritional composition of processed foods. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2012, 19, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund International. WCRF Nourishing Framework Improve Food Supply. Improve Nutritional Quality of the Whole Food Supply. Available online: http://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-framework/improve-food-supply (accessed on 18 September 2014).

- He, F.J.; Pombo-Rodrigues, S.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: Its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinsden, H.C.; He, F.J.; Jenner, K.H.; MacGregor, G.A. Surveys of the salt content in UK bread: Progress made and further reductions possible. BMJ Open 2013, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevena, H.; Dunford, E.; Neal, B.; Webster, J. The Australian Food and Health Dialogue—The implications of the sodium recommendation for pasta sauces. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. Public Health Responsibility Deal. Available online: https://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/ (accessed on 20 June 2014).

- Food and Health Dialogue, Meeting Summary. In Presented at the Food and Health Dialogue Executive 12th meeting, Canberra, Australia, May, 2013.

- Elliott, T.; Trevena, H.; Sacks, G.; Dunford, E.; Martin, J.; Webster, J.; Swinburn, B.; Moodie, R.; Wilson, A.; Neal, B. A systematic interim assessment of the Australian Government’s Food and Health Dialogue. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 200, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, C.; Buse, K. Public health sector and food industry interaction: It’s time to clarify the term ‘partnership’ and be honest about underlying interests. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 21, 400–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcand, J.; Au, J.T.C.; Schermel, A.; L’Abbe, M.R. A comprehensive analysis of sodium levels in the Canadian packaged food supply. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunford, E.; Eyles, H.; Mhurchu, N.C. Changes in the sodium content of bread in Australia in New Zealand between 2007 and 2010: Implications for policy. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 195, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoforou, A.K.; Dunford, E.K.; Neal, B.C. Changes in the sodium content of Australian ready meals between 2008 and 2011. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 22, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Otite, F.O.; Jacobson, M.F.; Dahmubed, A.; Mozaffarian, D. Trends in trans fatty acids reformulations of US supermarket and brand-name foods from 2007 through 2011. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2013, 10, (E85). 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.; Komitopoulou, E.; Incles, M. Evaluation of Technological Approaches to Salt Reduction. Available online: http://www.brc.org.uk/downloads/Leatherhead_Salt_Research.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2014).

- Institute of Medicine. Strategies to Reduce Sodium in the United States. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK50952 (accessed on 10 June 2014).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; Population Sodium Reduction Strategies. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/reducingsalt/en/ (accessed on 15 June 2014).

- Strazzullo, P.; D’Elia, L.; Kandala, N.B. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2009, 339, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, G.; King, S. Power without glory? Supermarket competition in Australia. Available online: http://monash.edu/news/show/power-without-glory-supermarket-competition-in-australia (accessed on 20 June 2014).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Sodium Levels in a Range of Packaged and Take-Away Foods. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/pages/sodiumlevelsinarange4648.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2014).

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Trevena, H.; Neal, B.; Dunford, E.; Wu, J.H.Y. An Evaluation of the Effects of the Australian Food and Health Dialogue Targets on the Sodium Content of Bread, Breakfast Cereals and Processed Meats. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3802-3817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6093802

Trevena H, Neal B, Dunford E, Wu JHY. An Evaluation of the Effects of the Australian Food and Health Dialogue Targets on the Sodium Content of Bread, Breakfast Cereals and Processed Meats. Nutrients. 2014; 6(9):3802-3817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6093802

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrevena, Helen, Bruce Neal, Elizabeth Dunford, and Jason H. Y. Wu. 2014. "An Evaluation of the Effects of the Australian Food and Health Dialogue Targets on the Sodium Content of Bread, Breakfast Cereals and Processed Meats" Nutrients 6, no. 9: 3802-3817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6093802

APA StyleTrevena, H., Neal, B., Dunford, E., & Wu, J. H. Y. (2014). An Evaluation of the Effects of the Australian Food and Health Dialogue Targets on the Sodium Content of Bread, Breakfast Cereals and Processed Meats. Nutrients, 6(9), 3802-3817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6093802