Major Cereal Grain Fibers and Psyllium in Relation to Cardiovascular Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

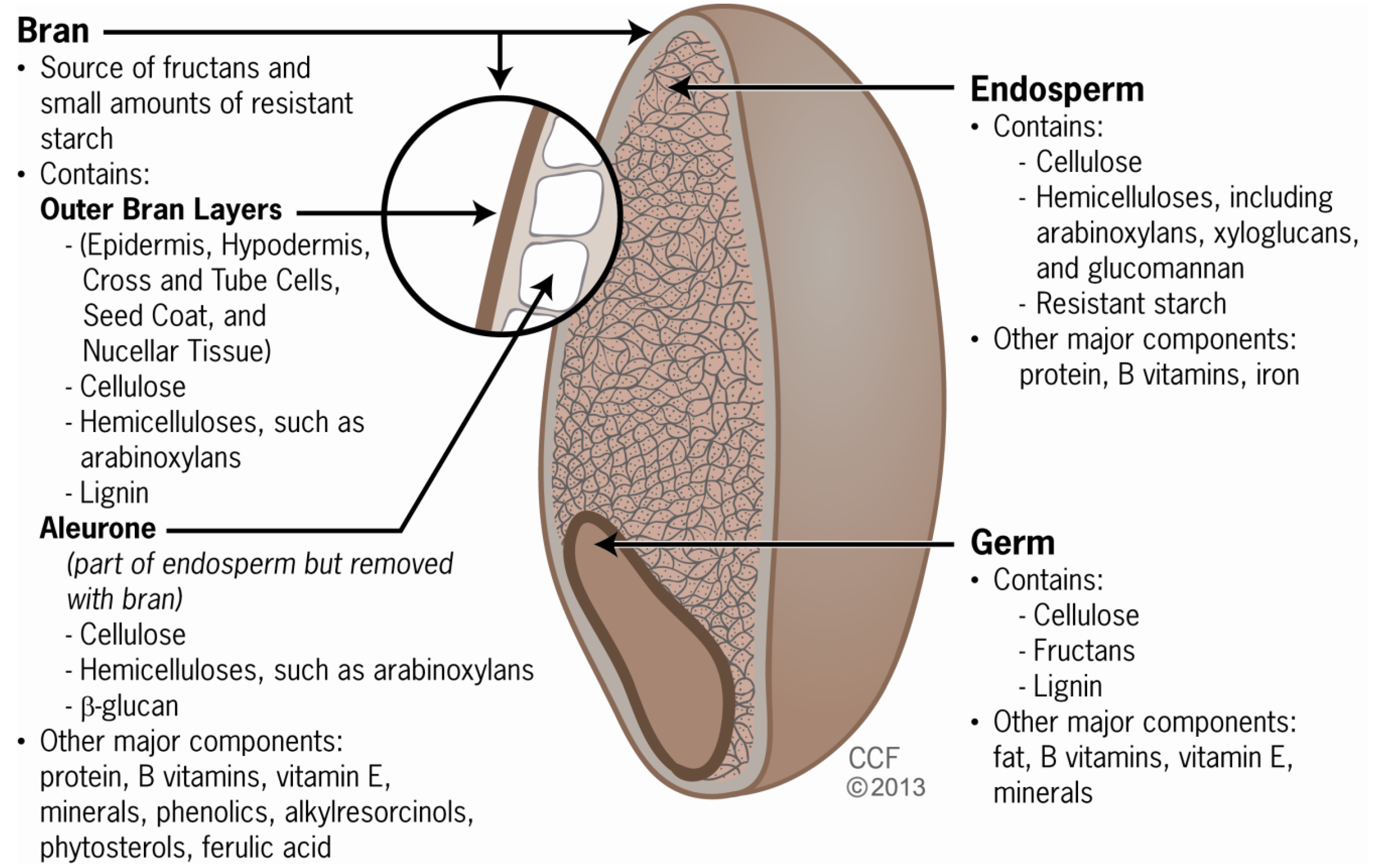

2. Grain Components and Fiber Types

| Fiber | Water Soluble (S) or Insoluble (I) | Viscosity | Fermentability | Major Cereal Sources | Properties that May Assist with Incorporation into Food [28] | Cardiovascular Benefit [29] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-glucans | S | Highly viscous | High | Oats, barley | Able to be added to a range of different products, including cereal, soup, beverages | ≥3 g/day of β-glucan soluble fiber from whole oats or barley, or a combination thereof, can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease |

| Arabinoxylans 2 | S | Viscous | High | Barley, wheat, rye, rice, sorghum, oats, corn millet | May lower glycemic index of breads, while providing pleasing mouth feel and tenderness | ≥7 g/day of soluble fiber from psyllium seed husk can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease |

| Inulin-Type Fructans | S | Mostly viscous | High | Wheat | Used to replace fat or carbohydrates without affecting taste or texture | Not yet established |

| Resistant Starch 3 | S | Non-viscous | Variable (rate and degree depend on source and heat treatment) | RS1: partially milled grainsRS3: cooked & cooled rice, pasta | Palatable and provides mouth feel of refined carbohydrates | Not yet established |

| First Author (year) | Number of included studies (Number of participants) (n) | Age (mean or median) and/or age range of participants (years) | Intervention (mean, median, or range of dose) | Intervention duration (mean and/or range, days) | Main findings (mg/dL) (95% CI) | Risk of publication bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ripsin (1992) [48] | 10 (1371) | 20–73 | Oat products (average soluble fiber dose range: 1.1–7.6 g/day) | 18–84 | TC: −5.9 (−8.4, −3.3) | Not reported |

| Larger reductions observed with 3 g/day in participants with TC ≥ 229 mg/dL | ||||||

| Brown (1999) [47] | 25 (1600) | 48 (26–61) | Oat products (average soluble fiber dose: 5 g/day with range of 1.5–13.0 g/day) | 39 (14–84) | TC: −1.55 (−1.93, −1.16) per g | Not reported |

| LDL: −1.55 (−1.55, −1.16) per g | ||||||

| Talati (2009) [45] | 8 (391) | Not reported | β-glucan from barley (7 g/day with range of 3–10 g/day) | 28–84 | TC: −13.38 (−18.46, −8.31) | Low |

| LDL: −10.02 (−14.03, −6.00) | ||||||

| TG: −11.83 (−20.12, −3.55) | ||||||

| AbuMweis (2010) [50] | 11 (591) | 20–63 | Barley or β-glucan from barley (5 g/day) | 28–84 | TC: −11.60 (−15.08, −8.12) | Possible (asymmetric funnel plots) |

| LDL: −10.44 (−13.15, −7.73) | ||||||

| Tiwari (2011) [49] | 20 (1154 (TC, LDL), 1000 (HDL)) | 18–72 | β-glucan (2–14 g/day) | 21–84 | TC: −23.2 (−32.9, −13.1) | Indeterminate (low risk by Eggers test, but possible risk by funnel plot) |

| LDL: −25.5(−37.1, −13.9) | ||||||

| HDL: 1.16 (−2.3, 5.03) with oat β-glucan | ||||||

| 3 g/day of β-glucan sufficient to decrease TC by 11.58 mg/dL | ||||||

| Olson (1997) [51] | 12 (404) | 27–72 | Psyllium-enriched cereal products (average soluble fiber dose range: 3–12 g/day) | 14–56 | TC: −11.99 (−14.31, −9.67) | Not reported |

| LDL: −13.53 (−15.47, −11.21) | ||||||

| Brown (1999) [47] | 17 (757) | 51 (44–59) | Psyllium (average soluble fiber dose 9.1 g/day with range of 4.7–16.2 g/day) | 53 (14–112) | TC: −1.5 (−1.93, −1.16) per g | Not reported |

| LDL: −2.7 (−5.8, −0.5) per g | ||||||

| Anderson (2000) [52] | 8 (384) | 55 (24–82) | Psyllium (10.2 g/day) | 56–182 | TC: −9.20 (−12.69, −5.71) | Not reported |

| LDL: −10.87 (−14.04, −7.70) | ||||||

| Wei (2009) [53] | 21 (1717) | Not reported | Psyllium (3–20.4 g/day) | 14–182 | TC: −14.50 (−9.94, −19.10) | Possible |

| LDL: −10.75 (−8.24, −12.06) | ||||||

| Dose response observed with 5, 10 and 15 g/day resulting in 5.6%, 9.0% and 12.5% decreases in LDL |

4. Arabinoxylan

5. Resistant Starch and Fructans

6. Biological Mechanisms

7. Public Health Fiber Recommendations and Implications

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Clemens, R.; Kranz, S.; Mobley, A.R.; Nicklas, T.A.; Raimondi, M.P.; Rodriguez, J.C.; Slavin, J.L.; Warshaw, H. Filling America’s fiber intake gap: Summary of a roundtable to probe realistic solutions with a focus on grain-based foods. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1390S–1401S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Nutrition Board of Institute of Medicine of National Academies Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Recommended dietary allowances and adequate intakes, total water and macronutrients. Available online: http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Nutrition/DRIs/5_Summary%20Table%20Tables%201-4.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2013).

- A Report of the Panel on Macronutrients Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients Interpretation Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. In Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients); The National Academies Press : Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesU.S. Department of AgricultureDietary Guidelines for Americans; Government Printing Office : Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Slavin, J.L. Dietary fiber and body weight. Nutrition 2005, 21, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimm, E.B.; Ascherio, A.; Giovannucci, E.; Spiegelman, D.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. Vegetable, fruit, and cereal fiber intake and risk of coronary heart disease among men. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1996, 275, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Kumanyika, S.K.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Olson, J.L.; Burke, G.L.; Siscovick, D.S. Cereal, fruit, and vegetable fiber intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly individual. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003, 289, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshak, E.S.; Iso, H.; Date, C.; Kikuchi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Wada, Y.; Wakai, K.; Tamakoshi, A. Dietary fiber intake is associated with reduced risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease among Japanese men and women. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.; O’Reilly, E.; Augustsson, K.; Fraser, G.E.; Goldbourt, U.; Heitmann, B.L.; Hallmans, G.; Knekt, P.; Liu, S.; Pietinen, P.; et al. Dietary fiber and risk of coronary heart disease: A pooled analysis of cohort studies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raninen, K.; Lappi, J.; Mykkanen, H.; Poutanen, K. Dietary fiber type reflects physiological functionality: Comparison of grain fiber, inulin, and polydextros. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture and Consumer Protection Department of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Physiologic Effects of Dietary Fibre. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/W8079E/w8079e0l.htm#TopOfPage (accessed on 15 December 2012).

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Cardiovascular benefits of dietary fiber. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2012, 14, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; van der, A.D.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Forouhi, N.G.; Wareham, N.J.; Halkjaer, J.; Tjonneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Boeing, H. Dietary fiber and subsequent changes in body weight and waist circumference in European men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, N.M.; Yoshida, M.; Shea, M.K.; Jacques, P.F.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Rogers, G.; Booth, S.L.; Saltzman, E. Whole-grain intake and cereal fiber are associated with lower abdominal adiposity in older adults. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkila, H.M.; Schwab, U.; Krachler, B.; Mannikko, R.; Rauramaa, R. Dietary associations with prediabetic states—the Dr’s EXTRA study (ISRCTN45977199). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, N.M.; Meigs, J.B.; Liu, S.; Saltzman, E.; Wilson, P.W.; Jacques, P.F. Carbohydrate nutrition, insulin resistance, and the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the Framingham Offspring Cohor. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez Coello, S.; Cabrera de Leon, A.; Rodriguez Perez, M.C.; Borges Alamo, C.; Carrillo Fernandez, L.; Almeida Gonzalez, D.; Garcia Yanes, J.; Gonzalez Hernandez, A.; Brito Diaz, B.; Aguirre-Jaime, A. Association between glycemic index, glycemic load, and fructose with insulin resistance: The CDC of the Canary Islands study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2010, 49, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Mirmiran, P.; Sohrab, G.; Hosseini-Esfahani, F.; Azizi, F. Inverse association between fruit, legume, and cereal fiber and the risk of metabolic syndrome: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 94, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, M.B.; Schulz, M.; Heidemann, C.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Boeing, H. Fiber and magnesium intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study and meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J. Why whole grains are protective: Biological mechanisms. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsivais, P.; Carter, B.E.; Christiansen, M.; Perrigue, M.M.; Drewnowski, A. Soluble fiber dextrin enhances the satiating power of beverages. Appetite 2011, 56, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United NationsWorld Health OrganizationGlobal Trends in Production and Consumption of Carbohydrate Foods; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization: Rome, Italy, 1998.

- McWilliams, M. Foods: Experimental Perspectives, 6th ed; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Munter, J.S.; Hu, F.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Franz, M.; van Dam, R.M. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishna, G.; Rao, M.V. Cereal non-cellulosic polysaccharides: Structure and function relationship—an overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.; Crispens, M.; Rothenberg, M.L. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: Overview and perspective. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2867–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlett, J.A.; Fischer, M.H. The active fraction of psyllium seed husk. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, J.M.; Haub, M.D. Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1266–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Government Printing Office Electronic Code of Federal Regulations: 101.81 health claims: Soluble fiber from certain foods and risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). Available online: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?c=ecfr;sid=502078d8634923edc695b394a357d189;rgn=div8;view=text;node=21%3A2.0.1.1.2.5.1.12;idno=21;cc=ecfr (accessed on 3 January 2013).

- Papathanasopoulos, A.; Camilleri, M. Dietary fiber supplements: Effects in obesity and metabolic syndrome and relationship to gastrointestinal functions. In Gastroenterology; 2010; Volume 138, pp. 65–72.e2. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, G.R.; Beatty, E.R.; Wang, X.; Cummings, J.H. Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria in the human colon by oligofructose and inulin. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 975–982. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.L.; Haack, V.S.; Janecky, C.W.; Vollendorf, N.W.; Marlett, J.A. Mechanisms by which wheat bran and oat bran increase stool weight in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 711–719. [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury, D.; Cuda, C.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Anderson, G.H. Beta glucan: Health benefits in obesity and metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 851362. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, L.; Phillips, F.; O’Sullivan, K.; Walton, J. Wheat bran: Its composition and benefits to health, a European perspective. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 63, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, M.; Albersheim, P. The structure of plant cell walls: VII. Barley aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 1975, 55, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milder, I.E.; Arts, I.C.; van de Putte, B.; Venema, D.P.; Hollman, P.C. Lignan contents of dutch plant foods: A database including lariciresinol, pinoresinol, secoisolariciresinol and matairesino. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.A.; Andersson, R.; Piironen, V.; Lampi, A.M.; Nystrom, L.; Boros, D.; Fras, A.; Gebruers, K.; Courtin, C.M.; Delcour, J.A. Contents of dietary fibre components and their relation to associated bioactive components in whole grain wheat samples from the healthgrain diversity screen. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; Stephen, A.M. Carbohydrate terminology and classification. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, S5–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.X.; Walker, K.Z.; Muir, J.G.; Mascara, T.; O’Dea, K. Arabinoxylan fiber, a byproduct of wheat flour processing, reduces the postprandial glucose response in normoglycemic subject. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, I.T. Chapter 8: Dietary Fiber, 10th ed; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Asp, N.G.; van Amelsvoort, J.M.; Hautvast, J.G. Nutritional implications of resistant starch. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1996, 9, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brounds, F.; Adam-Perrot, A.; Atwell, B.; Reding, W. Nutritional and Technological Aspects of Wheat Aleurone Fibre: Implications for Use in Food; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gropper, S.S.; Smith, J.L. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism, 6th ed; Wadsworth, Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahan, L.K.; Escott-Stump, S.; Raymond, J.L. Krause’s Food & Nutrition Therapy, 12th ed; Saunders Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Talati, R.; Baker, W.L.; Pabilonia, M.S.; White, C.M.; Coleman, C.I. The effects of barley-derived soluble fiber on serum lipids. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009, 7, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braaten, J.T.; Wood, P.J.; Scott, F.W.; Wolynetz, M.S.; Lowe, M.K.; Bradley-White, P.; Collins, M.W. Oat beta-glucan reduces blood cholesterol concentration in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 48, 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.W.; Sacks, F.M. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ripsin, C.M.; Keenan, J.M.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Elmer, P.J.; Welch, R.R.; van Horn, L.; Liu, K.; Turnbull, W.H.; Thye, F.W.; Kestin, M.; et al. Oat products and lipid lowering. A meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1992, 267, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, U.; Cummins, E. Meta-analysis of the effect of beta-glucan intake on blood cholesterol and glucose levels. Nutrition 2011, 27, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuMweis, S.S.; Jew, S.; Ames, N.P. Beta-glucan from barley and its lipid-lowering capacity: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.H.; Anderson, S.M.; Becker, M.P.; Anderson, J.W.; Hunninghake, D.B.; Jenkins, D.J.; LaRosa, J.C.; Rippe, J.M.; Roberts, D.C.; Stoy, D.B.; et al. Psyllium-enriched cereals lower blood total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, but not HDL cholesterol, in hypercholesterolemic adults: Results of a meta-analysis. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.W.; Allgood, L.D.; Lawrence, A.; Altringer, L.A.; Jerdack, G.R.; Hengehold, D.A.; Morel, J.G. Cholesterol-lowering effects of psyllium intake adjunctive to diet therapy in men and women with hypercholesterolemia: Meta-analysis of 8 controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 472–479. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.H.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, B.S.; Rong, Z.X.; Su, B.H.; Chen, H.Z. Time- and dose-dependent effect of psyllium on serum lipids in mild-to-moderate hypercholesterolemia: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A.L.; Otto, B.; Reich, S.C.; Weickert, M.O.; Steiniger, J.; Machowetz, A.; Rudovich, N.N.; Mohlig, M.; Katz, N.; Speth, M.; et al. Arabinoxylan consumption decreases postprandial serum glucose, serum insulin and plasma total ghrelin response in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.L.; Steiniger, J.; Reich, S.C.; Weickert, M.O.; Harsch, I.; Machowetz, A.; Mohlig, M.; Spranger, J.; Rudovich, N.N.; Meuser, F.; et al. Arabinoxylan fibre consumption improved glucose metabolism, but did not affect serum adipokines in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Horm. Metab. Res. 2006, 38, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.X.; Walker, K.Z.; Muir, J.G.; O’Dea, K. Arabinoxylan fibre improves metabolic control in people with type II diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloetens, L.; Broekaert, W.F.; Delaedt, Y.; Ollevier, F.; Courtin, C.M.; Delcour, J.A.; Rutgeerts, P.; Verbeke, K. Tolerance of arabinoxylan-oligosaccharides and their prebiotic activity in healthy subjects: A randomised, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, B.; Cloetens, L.; Broekaert, W.F.; Francois, I.; Lescroart, O.; Trogh, I.; Arnaut, F.; Welling, G.W.; Wijffels, J.; Delcour, J.A.; et al. onsumption of breads containing in situ-produced arabinoxylan oligosaccharides alters gastrointestinal effects in healthy volunteers. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, J.E.; Forman, D.T.; Eiseman, W.R.; Phillips, C.R. Lowering of human serum cholesterol by an oral hydrophilic colloid. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1965, 120, 744–746. [Google Scholar]

- Sola, R.; Godas, G.; Ribalta, J.; Vallve, J.C.; Girona, J.; Anguera, A.; Ostos, M.; Recalde, D.; Salazar, J.; Caslake, M.; et al. Effects of soluble fiber (Plantago ovata husk) on plasma lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins in men with ischemic heart diseas. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, V.; Hodgson, J.M.; Beilin, L.J.; Giangiulioi, N.; Rogers, P.; Puddey, I.B. Dietary protein and soluble fiber reduce ambulatory blood pressure in treated hypertensives. Hypertension 2001, 38, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englyst, K.N.; Liu, S.; Englyst, H.N. Nutritional characterization and measurement of dietary carbohydrates. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, S19–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.M.; Douglass, J.S.; Birkett, A. Resistant starch intakes in the United States. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantle, J.P.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Albright, A.L.; Apovian, C.M.; Clark, N.G.; Franz, M.J.; Hoogwerf, B.J.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Mooradian, A.D.; et al. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, S61–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.C.; Pelkman, C.L.; Finocchiaro, E.T.; Kelley, K.M.; Lawless, A.L.; Schild, A.L.; Rains, T.M. Resistant starch from high-amylose maize increases insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese men. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, M.; Clifton, P.M.; Nestel, P.J.; Le Leu, R.; McIntosh, G. Effect of high-amylose starch and oat bran on metabolic variables and bowel function in subjects with hypertriglyceridemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 64, 944–951. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, K.L.; Thomas, E.L.; Bell, J.D.; Frost, G.S.; Robertson, M.D. Resistant starch improves insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.D.; Currie, J.M.; Morgan, L.M.; Jewell, D.P.; Frayn, K.N. Prior short-term consumption of resistant starch enhances postprandial insulin sensitivity in healthy subjects. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 659–665. [Google Scholar]

- Behall, K.M.; Scholfield, D.J.; Hallfrisch, J.G.; Liljeberg-Elmstahl, H.G. Consumption of both resistant starch and beta-glucan improves postprandial plasma glucose and insulin in women. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M.B. Inulin-type fructans: Functional food ingredients. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2493S–2502S. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsu, N.K.; Johnson, C.S.; McLeod, K.M. Can dietary fructans lower serum glucose? J. Diabetes 2011, 3, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighenti, F. Dietary fructans and serum triacylglycerols: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2552S–2556S. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, E.J.; Tosh, S.M.; Batterham, M.J.; Tapsell, L.C.; Huang, X.F. Oat beta-glucan increases postprandial cholecystokinin levels, decreases insulin response and extends subjective satiety in overweight subjects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, K.R.; Purhonen, A.K.; Salmenkallio-Marttila, M.; Lahteenmaki, L.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Herzig, K.H.; Uusitupa, M.I.; Poutanen, K.S.; Karhunen, L.J. Viscosity of oat bran-enriched beverages influences gastrointestinal hormonal responses in healthy humans. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Weickert, M.O.; Mohlig, M.; Koebnick, C.; Holst, J.J.; Namsolleck, P.; Ristow, M.; Osterhoff, M.; Rochlitz, H.; Rudovich, N.; Spranger, J.; et al. Impact of cereal fibre on glucose-regulating factors. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 2343–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Kendall, C.W.; Axelsen, M.; Augustin, L.S.; Vuksan, V. Viscous and nonviscous fibres, nonabsorbable and low glycaemic index carbohydrates, blood lipids and coronary heart diseas. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2000, 11, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H.J.; Eldridge, A.L.; Beiseigel, J.; Thomas, W.; Slavin, J.L. Greater satiety response with resistant starch and corn bran in human subjects. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Guenther, P.M.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Dodd, K.W. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1832–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Ho, S.C.; Cheng, S.Z.; Chen, Y.M.; Fu, J.H.; Lin, F.Y. Effect of dietary fiber intake on breast cancer risk according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklas, T.A.; O’Neil, C.E.; Liska, D.J.; Almeida, N.G.; Fulgoni, V.L. Modeling dietary fiber intakes in us adults: Implications for public policy. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 2, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, release 25. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/main/site_main.htm?modecode=12-35-45-00 (accessed on 29 March 2013).

- Livesey, G. Energy values of unavailable carbohydrate and diets: An inquiry and analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 51, 617–637. [Google Scholar]

- Hiza, H.; Fungwe, T.; Bente, L. Trends in Dietary Fiber in the U.S. Food Supply; Sales of Grain Products: Crop Fact Sheet No 2; United States Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bosscher, D.; van Caillie-Bertrand, M.; van Cauwenbergh, R.; Deelstra, H. Availabilities of calcium, iron, and zinc from dairy infant formulas is affected by soluble dietary fibers and modified starch fractions. Nutrition 2003, 19, 641–645. [Google Scholar]

- Wrick, K.; Robertson, J.; van Soest, P.; Lewis, B.; Rivers, J.; Roe, D.; Hackler, L. The influence of dietary fiber source on human intestinal transit and stool output. J. Nutr. 1983, 11, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt, D.P.; Walker, A.R.; Painter, N.S. Effect of dietary fibre on stools and the transit-times, and its role in the causation of disease. Lancet 1972, 2, 1408–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonithon-Kopp, C.; Kronborg, O.; Giacosa, A.; Rath, U.; Faivre, J. Calcium and fibre supplementation in prevention of colorectal adenoma recurrence: A randomised intervention trial.European cancer prevention organisation study group. Lancet 2000, 365, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Anti, M.; Pignataro, G.; Armuzzi, A.; Valenti, A.; Iascone, E.; Marmo, R.; Lamazza, A.; Pretaroli, A.R.; Pace, V.; Leo, P.; et al. Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology 1998, 45, 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.; Khossousi, A.; Binns, C.; Dhaliwal, S.; Ellis, V. The effect of a fibre supplement compared to a healthy diet on body composition, lipids, glucose, insulin and other metabolic syndrome risk factors in overweight and obese individua. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernstein, A.M.; Titgemeier, B.; Kirkpatrick, K.; Golubic, M.; Roizen, M.F. Major Cereal Grain Fibers and Psyllium in Relation to Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1471-1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051471

Bernstein AM, Titgemeier B, Kirkpatrick K, Golubic M, Roizen MF. Major Cereal Grain Fibers and Psyllium in Relation to Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients. 2013; 5(5):1471-1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051471

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernstein, Adam M., Brigid Titgemeier, Kristin Kirkpatrick, Mladen Golubic, and Michael F. Roizen. 2013. "Major Cereal Grain Fibers and Psyllium in Relation to Cardiovascular Health" Nutrients 5, no. 5: 1471-1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051471

APA StyleBernstein, A. M., Titgemeier, B., Kirkpatrick, K., Golubic, M., & Roizen, M. F. (2013). Major Cereal Grain Fibers and Psyllium in Relation to Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients, 5(5), 1471-1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5051471