1. Introduction

Xanthohumol (XN) is a prenylated chalcone flavonoid derived from hops (Humulus lupulus), best known as a bioactive component of hops and beer. In recent years, XN has attracted broad research interest because it modulates multiple disease-relevant pathways involving inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolism, and cell survival. Rather than acting on a single molecular target, XN functions as a pleiotropic regulator, allowing it to influence a wide range of biological processes.

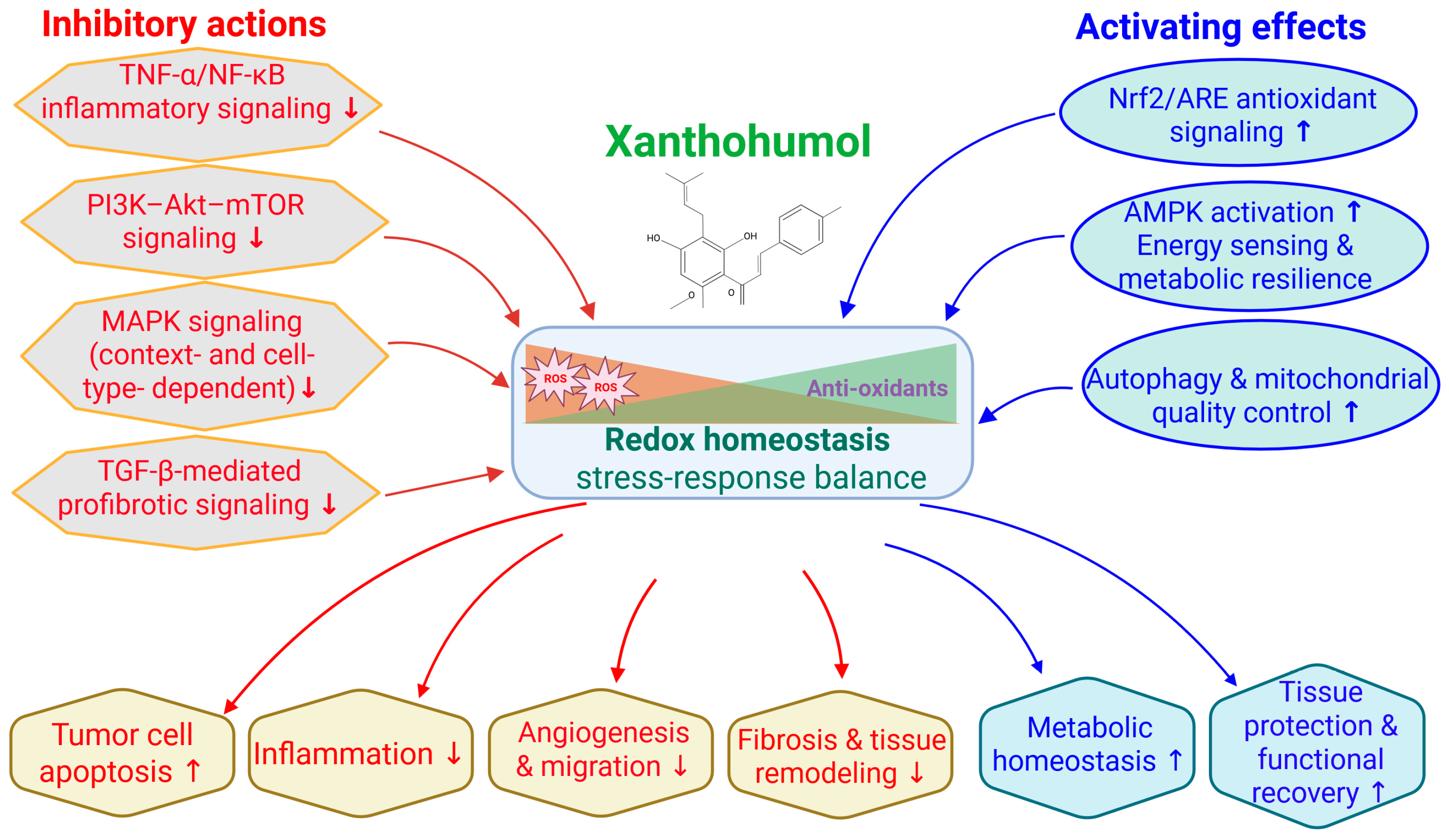

A growing body of research has demonstrated that XN possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor properties across diverse experimental systems. In cancer biology, XN preferentially targets malignant cells over matched normal counterparts, consistent with selective vulnerability to mitochondrial stress and cell cycle disruption. In addition to direct effects on tumor cells, XN influences the tumor microenvironment by suppressing angiogenesis and inflammatory signaling, thereby limiting tumor growth and progression (

Figure 1).

Beyond oncology, XN exhibits antimicrobial and antiviral activity and confers protection in neurological, metabolic, cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and dermatologic models. Across these contexts, XN preserves mitochondrial integrity, attenuates oxidative and inflammatory injury, and mitigates tissue damage associated with ischemia, metabolic stress, and chronic inflammation (

Figure 1). Collectively, these observations support the view that XN acts on conserved cellular stress-response pathways that are relevant across multiple disease settings. Together, these observations reinforce the concept that XN influences conserved cellular stress-response pathways that are relevant across multiple disease settings.

Human studies demonstrate that oral XN is safe and well tolerated with observed broad therapeutic promises. However, its hydrophobic nature and rapid biotransformation pose challenges for systemic delivery. Ongoing formulation improvements, such as micellar encapsulation, have begun to enhance its bioavailability and translational potential [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

In this review, a comprehensive literature search was conducted between 2000 and December 2025 using multiple scientific databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, and the MDPI database, to identify relevant studies on XN. The search strategy employed the keywords “xanthohumol” and “Humulus lupulus” in combination with disease- and mechanism-related terms, such as “cancer,” “neuroprotection,” “inflammation,” “oxidative stress,” “metabolism,” “AMPK,” “Nrf2,” and “NF-κB.” Inclusion criteria comprised full-text original research articles and human studies published in English that investigated the biological activity, molecular mechanisms, or safety of XN. Review articles were screened to identify additional relevant primary studies. Exclusion criteria included preprints, studies lacking compound characterization or purity information, and reports in which XN was not the primary bioactive compound discussed in the abstract. The publications identified through this process formed the core literature base for this integrative mechanistic and translational review.

In summary, current findings position XN as a versatile natural compound with potential applications spanning cancer therapy, neuroprotection, metabolic regulation and inflammatory disease management. Continued mechanistic and clinical investigations, including efforts to improve formulations, will be required to define its effective nutraceutical efficacy in the future.

Several sector-specific reviews have previously examined XN in individual disease contexts, including oncology, metabolic disorders, and cardiometabolic diseases. However, an integrated synthesis that reconciles these findings through shared mechanistic frameworks and translational relevance remains lacking. Accordingly, the present review does not aim to provide an exhaustive enumeration of all reported biological effects of XN. Instead, it adopts a mechanism-centered perspective, organizing evidence across disease areas according to convergent stress-response and metabolic signaling networks, with particular emphasis on redox modulation by inhibiting NF-κB and activating Nrf2 signaling axes (

Figure 2).

By structuring the literature around these core regulatory nodes, this review highlights how apparently diverse outcomes—such as antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, neuroprotective, cardiometabolic, and hepatoprotective effects—arise from a limited set of interconnected upstream events rather than independent pathway-specific actions. Mechanistic details are therefore developed within the relevant disease sections, while translational considerations, including nutraceutical relevance, formulation, bioavailability, and human safety data, are integrated throughout. This approach is intended to bridge preclinical mechanistic insights with emerging human evidence and to clarify the potential positioning of XN at the interface of dietary bioactives and drug-like therapeutics.

2. Anticancer Effects

XN exhibits potent anticancer effects across diverse malignancies through multi-targeted mechanisms, including inhibition of NF-κB and AKT signaling, induction of mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis, and suppression of angiogenesis.

2.1. Cellular and In Vivo Anticancer Effects of XN

Antiproliferation: Concentration-dependent antiproliferative effects of XN have been consistently observed across multiple cancer cell types. Importantly, XN demonstrates notable selectivity for malignant cells over their normal counterparts. For example, the IC

50 for normal CDD-18Co colon fibroblasts exceeded 100 µM, whereas the IC

50 for HT-29 colon cancer cells was approximately 10 µM [

14]. Sensitivity to XN is also influenced by the spatial architecture of the tissue model. In three-dimensional (3D) culture systems, cancer cells exhibited reduced susceptibility compared with two-dimensional (2D) monolayers: IC

50 values for MCF-7 and A549 spheroids increased to 12.37 µM and 31.17 µM, respectively, compared with 1.9 µM and 4.74 µM in 2D cultures [

15]. This difference underscores the importance of microenvironmental context in modulating XN responsiveness.

Cell cycle arrest and apoptotic induction: XN modulates key regulators of cell cycle progression, leading to arrest at various phases depending on the cancer type, with G

1 and G

2/M checkpoints most affected. G

1 arrest is associated with reduced cyclin D1 expression [

16] and upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 [

8], whereas G

2/M arrest correlates with depletion of cyclin B and increased phosphorylation of CDK1 (formerly cdc2) [

14]. XN also elevates p53 levels [

17], indicating activation of p53-dependent checkpoint pathways.

XN induces apoptosis across diverse malignancies through both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. Hallmarks of apoptosis have been consistently reported, including nuclear fragmentation [

14], DNA laddering [

18], chromatin condensation [

19], phosphatidylserine externalization [

20], an increased ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 [

14], activation of initiator caspases (caspase-8 and caspase-9) and executioner caspase-3 [

18], loss of mitochondrial membrane potential [

18], and release of cytochrome c [

21].

Representative in vitro studies demonstrating the anticancer activity of XN across diverse tumor types, including colon, breast, lung, and hematologic malignancies, are summarized in

Table 1.

In vivo tumor inhibition: XN has demonstrated robust antitumor activity across multiple animal- and patient-derived xenograft models, as summarized in

Table 2. In SG-231 cholangiocarcinoma xenografts, XN treatment resulted in a fivefold reduction in tumor size by day 16 compared with untreated controls [

22]. In a CCLP-1 model, XN suppressed tumor growth by 78%, whereas tumors in the control group expanded by 853% over the same period [

22]. XN-treated tumors consistently showed a reduction in Ki-67 expression [

23], along with an increase in central necrosis and apoptotic markers [

24].

Anti-angiogenic effects: XN exhibits potent anti-angiogenic properties mediated largely through suppression of NF-κB-dependent VEGF and IL-8 expression. In breast cancer xenografts, oral XN administration reduced microvessel density and lowered numbers of endothelial cells, with NF-κB activity decreasing to approximately 60% of control values [

24]. In pancreatic cancer cell lines (BxPC-3), XN inhibited VEGF and IL-8 production and blocked tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [

25]. Correspondingly, in BxPC-3 xenografts, XN significantly reduced CD31-positive microvessel density [

25], confirming anti-angiogenic effects in vivo. Additional evidence comes from melanoma metastasis models, where XN-treated mice displayed enlarged areas of central necrosis within liver lesions, consistent with restricted blood supply [

23]. Studies in multiple myeloma further showed decreased VEGF secretion following XN exposure [

26], supporting its broad anti-angiogenic activity.

Anti-metastasis: XN inhibited multiple steps in the metastatic cascade, including cell migration, invasion, and adhesion to endothelial cells. XN suppressed leukemic cell invasion, metalloprotease production, and adhesion to endothelial cells, potentially preventing life-threatening complications of leukostasis and tissue infiltration [

17]. In the acute lymphocytic leukemia model, administration of XN (2 mg/kg, assuming a 25g mouse) significantly prolonged animal lifespan by delaying neurological complications with leukemic dissemination [

27]. XN also showed dose-dependent inhibition of melanoma cell migration in vitro and markedly reduced hepatic metastasis formation in vivo [

23]. Mechanistically, studies from 3D cultures revealed that XN suppressed key invasion-related genes, including MMP2, MMP9, and FAK, accompanied by disruption of the actin microfilament network [

15]. Collectively, these data support a multifaceted anti-metastatic role for XN across diverse tumor types.

2.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Although XN has been reported to modulate multiple signaling pathways, such actions are not independent or in parallel. Instead, available evidence supports a hierarchical and interconnected mechanism in which a limited number of primary molecular events initiate broader downstream responses. The core of XN’s anticancer activity is direct redox-sensitive interactions between key regulatory proteins and mitochondria, leading to oxidative stress modulation and mitochondrial dysfunction. These primary events subsequently suppress central survival and inflammatory signaling nodes, most prominently the NF-κB and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Inhibition of these master regulators then drives secondary effects on angiogenesis, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and metastatic behavior. Additional pathways, including MAPK and Notch signaling, appear to be context-dependent modulators that fine-tune cellular responses rather than universal primary targets. Framing XN’s actions within this mechanistic hierarchy helps reconcile its broad biological activity while emphasizing a coherent and biologically plausible mode of action (

Figure 2).

NF-κB Pathway: XN directly targets key regulatory components of the NF-κB pathway by covalently modifying critical cysteine residues in IκB kinase (IKK) and p65, leading to inhibition of IKK activation, suppression of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, and prevention of p65 nuclear translocation, thus decreasing NF-κB-dependent transcription [

28]. Mutating these residues abolished XN’s effects [

28], confirming their functional importance. XN demonstrated a 40% reduction in NF-κB activity in an MDA-MB-231 (

Table 1) breast cancer xenograft [

24] and inhibition of both constitutive and inducible NF-κB signaling in pancreatic cancer models [

25]. Downstream consequences included reductions in anti-apoptotic proteins (survivin, Bcl-xL, XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2) [

28], alongside decreases in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β) [

24] and angiogenic factors (VEGF and IL-8) [

25]. These combined effects contribute to XN’s ability to promote apoptosis, suppress inflammation, and impair tumor angiogenesis.

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway: XN inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade through direct and indirect mechanisms. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (KYSE70, KYSE450, and KYSE510;

Table 1), which exhibit substantial biological heterogeneity, XN acted as an ATP-competitive inhibitor of AKT1/2, with computational docking models supporting direct binding to the kinase domain. This inhibition led to decreased phosphorylation of key downstream targets such as GSK3β, mTOR, and S6K, resulting in reduced cyclin D1 expression and G

1-phase cell cycle arrest [

29]. Similar findings were reported in gastric cancer models, where XN suppressed phosphorylation of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR in vivo [

30]. In leukemia, XN-mediated downregulation of AKT signaling correlated with reduced cell viability and enhanced apoptosis [

17]. These results collectively indicate that XN effectively disrupts PI3K/AKT/mTOR-driven survival and proliferation pathways across multiple tumor types.

Notch Signaling: XN exerts potent antitumor effects through inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway. In ovarian cancer cell lines (e.g., SKOV3 and OVCAR3), XN significantly suppressed cell growth by downregulating Notch1 transcription and protein expression, accompanied by increased Hes6 and decreased Hes1 transcription, with disrupted Notch signaling [

31]. In pancreatic cancer models, XN reduced Notch promoter activity and downstream Notch effectors such as Hes-1, thus suppressing cell surviving. Enforced expression of constitutively active Notch1 reversed XN-mediated growth inhibition, confirming Notch1 as a direct functional target [

32]. In cholangiocarcinoma cell lines (CCLP-1 and SG-231;

Table 1), XN induced a time-dependent, stepwise reduction in Notch1 expression as early as 12 h after treatment, preceding later decreases in AKT phosphorylation [

22]. This temporal sequence suggests mechanistic crosstalk in which Notch1 suppression contributes to downstream PI3K/AKT pathway attenuation. Collectively, these observations establish Notch1 inhibition as a key upstream event in XN’s anti-proliferative action across multiple tumor types.

MAPK Pathways: XN modulates multiple members of the MAPK family, producing context-dependent effects across cancer types. In HT-29 colon cancer cells (

Table 1), XN induced a concentration-dependent blockade of the MEK/ERK, contributing to growth suppression [

14]. In multiple myeloma, ERK and JNK activation were identified as essential mediators of XN-induced apoptosis; inhibition of these kinases or pretreatment with N-acetylcysteine prevented caspase-3 activation and apoptotic cell death [

26]. In laryngeal cancer cells (

Table 1), inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by XN was identified as a key mechanism underlying reduced cell proliferation [

16]. In melanoma models, including B16-F10 cells (

Table 1 and

Table 2), XN inhibited JNK phosphorylation while modestly increasing p38 MAPK activation, indicating differential regulation of MAPK subfamilies [

23]. In glioblastoma, XN activated the ERK/c-Fos axis, leading to upregulation of miR-204-3p, which subsequently suppressed the IGFBP2/AKT/Bcl-2 pathway [

33]. Collectively, these findings indicate that XN targets multiple MAPK targets, with inhibitory or activating effects depending on the cellular context, ultimately converging on pathways that regulate growth arrest, apoptosis, and stress responses.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and ROS Generation: XN-induced mitochondrial dysfunction through multiple mechanisms. A comprehensive mechanistic study in human cancer cell lines (

Table 1) identified mitochondria as the primary site of superoxide anion generation following XN exposure, with EC

50 values of XN 3.1 µM in human cancer cell lines and 11.4 µM in isolated mitochondria [

34]. XN resulted in rapid ATP depletion (IC

50 = 26.7 µM within 15 min), a 15% increase in oxidized glutathione, and dose-dependent thiol depletion (IC

50 = 24.3 µM) [

34]. The XN inhibited electron flux from respiratory chain complexes I and II to complex III, with IC

50 values of 28.1 and 24.4 µM, respectively, leading to collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential and release of cytochrome c [

34]. Importantly, antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine and MnTMPyP prevented XN-induced mitochondrial depolarization and apoptosis, confirming ROS generation as a key upstream trigger of XN’s cytotoxic activity [

34]. Consistent with this mechanism, numerous studies have reported ROS production as a central component of XN’s anticancer effects [

17].

Other Molecular Targets: Beyond its effects on the above major signaling pathways, XN interacts with several specific molecular targets. In esophageal squamous carcinoma cell lines, KYSE70, KYSE450, and KYSE510 (

Table 1), XN was shown to bind keratin 18 and promote its degradation without altering mRNA expression [

21]. In leukemia models, XN inhibited Bcr-Abl expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, contributing to reduced cell viability and enhanced apoptosis [

17].

Synergistic Effects with Chemotherapy: XN has demonstrated strong chemosensitizing properties across multiple cancer models. In H1299 lung cancer cells (

Table 1), XN enhanced cisplatin-induced DNA damage, with the combination producing greater γH2AX foci formation, a hallmark of DNA double-strand breaks, suggesting that XN could sensitize tumor cells to DNA-damaging chemonutraceuticals more than either agent alone [

19]. XN at 6.25 or 12.5 µM in the H1299 lines enhanced cisplatin-induced apoptosis by activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of PARP-1 [

19]. Drug-resistant breast cancer cell models (MDA-MB-231;

Table 1) demonstrated that XN downregulated MDR1, EGFR, and STAT3, thereby restoring sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy [

35]. Importantly, in acute lymphocytic leukemia, cells that adapted to long-term XN exposure became highly responsive to other cytotoxic drugs [

27]. These findings highlight XN’s capacity to prime tumor cells for enhanced susceptibility to sequential or alternating treatment strategies.

XN also exhibits protection of normal DNA damage in response to chemotherapy. In a rat model, XN protected against genotoxic injury induced by the heterocyclic aromatic amine IQ, a dietary carcinogen [

36]. Animals consuming XN-supplemented drinking water showed reductions in preneoplastic GST-p+ foci and DNA migration in both colon mucosae and liver cells [

36]. Together, these findings highlight XN’s dual ability to protect normal tissues from carcinogen-induced DNA damage while potentiating DNA damage-based cancer therapies.

Table 1.

In vitro anticancer effects of xanthohumol across tumor types.

Table 1.

In vitro anticancer effects of xanthohumol across tumor types.

| Cancer Type | Cell Line (In Vitro) | Xanthohumol Concentration | Key Biological Outcomes | Primary Mechanistic Actions | Ref. |

|---|

| Colon | HT-29 | IC50 = 10 µM | Growth inhibition; G2/M arrest | Cyclin B1 downregulation | [14] |

| Breast | MDA-MB-231 | 10–20 µM (2d) | Reduced survival; apoptosis induction | Intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis (caspase-3/9 activation) | [18] |

| Breast (3D) | MCF-7 | IC50: 1.9 µM (2D); 12.37 µM (3D) | Increased apoptosis and necrosis | Reduced sensitivity in 3D spheroids | [15] |

| Lung (3D) | A549 | IC50: 4.74 µM (2D); 31.17 µM (3D) | Increased apoptosis and necrosis | Reduced sensitivity in 3D spheroids | [15] |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | CCLP-1 | 5–15 µM (2–4 d) | Time-dependent growth inhibition | G0/G1 arrest; caspase-3 activation; PARP cleavage | [22] |

| SG-231 | 5–15 µM (2–4 d) | Time-dependent growth inhibition | G0/G1 arrest; caspase-3 activation; PARP cleavage | [22] |

| CC-SW-1 | 5–15 µM (2–4 d) | Time-dependent growth inhibition | G0/G1 arrest; caspase-3 activation; PARP cleavage | [22] |

| Cervical | Ca Ski | IC50: 20–60 µM (2–3d) | Apoptosis induction; S-phase accumulation | S-phase cell cycle blockade | [20] |

| Esophageal | KYSE70/450/510 | 5 µM | 70–80% growth inhibition; apoptosis | Cyclin D1 downregulation; G1 arrest | [29] |

| Ovarian | EOC lines | N.A. | S and G2/M arrest | Cell cycle checkpoint activation (p21, CDK1 modulation) | [31] |

| Thyroid | Human thyroid cells | N.A. | Cell cycle redistribution | G1 reduction; S-phase increase | [37] |

| Larynx | Larynx cancer cells | N.A. | Cell cycle arrest; apoptosis-related signaling | p53 and p21/WAF1 induction; Bcl-2 downregulation | [16] |

| Multiple myeloma | Myeloma cells | N.A. | Cell cycle blockade | Cyclin D1 downregulation; p21 induction | [26] |

| Lung | H1299 | Xanthohumol ± cisplatin | Enhanced apoptosis vs. monotherapy | Chemosensitization via caspase-3 activation | [19] |

Table 2.

In vivo anticancer effects of xanthohumol across tumor types.

Table 2.

In vivo anticancer effects of xanthohumol across tumor types.

| Cancer Type | Animal Model/PDX System | Treatment (Dose, Route, Duration) | Primary Outcome | Mechanism Notes | Ref. |

|---|

| Breast | MCF7 xenograft (nude mice) | Oral XN; per study regimen | Central necrosis; ↓ inflammatory cells; ↑ apoptosis | Anti-angiogenic/anti-inflammatory context | [24] |

| Liver/colon (preneoplasia) | Rat model | 71 µg/kg in drinking water | ↓ GST-p+ foci 50%; ↓ foci area 44% | Suppression of preneoplastic lesions and DNA damage | [36] |

| Melanoma (metastasis) | B16-F10 (C57BL/6) | 10 mg/kg i.p. pellets | ↓ Hepatic metastasis & overall tumor load | Anti-metastatic effect | [23] |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | SG-231 xenograft (nude) | 5 mg/kg i.p. qod × 16 days | Growth: 427%→153% (day 8); 1308%→255% (day 16) | Notch1/AKT inhibition | [22] |

| CCLP-1 xenograft (nude) | 5 mg/kg i.p. qod × 16 days | Growth: 381%→−13% (day 8); 853%→−78% (day 16) | Notch1/AKT inhibition | [22] |

| Pancreatic | BxPC-3 xenograft | Weekly i.p. injections | ↓ Tumor volume (significant) | NF-κB suppression | [25] |

| Gastric | SGC-7901 xenograft | 0.5–1 mg/kg, i.p., once daily × 3 weeks | ↓ Tumor volume & weight | PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibition | [30] |

| Esophageal | KYSE30 PDX (SCID mice) | 40–160 mg/kg OG, daily × 64 d | Significant tumor growth decrease | AKT/MAPK axis modulation | [21] |

| High-AKT PDX(SCID mice) | 80–160 mg/kg OG, daily × 50 d | ↓ Tumor volume & weight (greater in high-AKT) | AKT dependency noted | [29] |

3. Antiviral and Antimicrobial Effects

XN exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, demonstrating potent effects against drug-resistant bacteria, coronaviruses, hepatitis C virus (HCV), HIV-1, parasites, and fungi. Its mechanisms include membrane disruption, inhibition of viral protease, and interference with key replication pathways. In addition, reported therapeutic indices indicate a favorable safety margin, underscoring XN’s potential as a multifunctional antimicrobial agent.

3.1. Antimicrobial and Antiviral Activity of XN

Antimicrobial effects: XN demonstrates potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including clinically significant drug-resistant strains. XN at 84.3% purity produced marked reductions in

Clostridioides difficile (strain 176) by day 3 in a rat infection model, representing the strongest antimicrobial effect among the hop-derived compounds [

38]. Purified XN exhibited MIC values ranging from 15 to 107 μg/mL against toxigenic

C. difficile isolates, with activity approaching that of standard antibiotics even in resistant strains [

39], demonstrating XN’s potential as a promising candidate for managing difficult-to-treat Gram-positive infections.

Against

Staphylococcus aureus, pure XN exhibited exceptional potency, achieving an MIC of 3.9 μg/mL against MRSA ATCC 43300—classified as very strong antimicrobial activity by established criteria [

40]. Remarkably, XN maintained comparable efficacy against both methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive strains, with MIC values around 4 mg/L for

staphylococci and complete bacterial reduction at approximately 60 μg/mL in biofilm assays [

40,

41]. In biofilm eradication studies, XN at the MIC concentration reduced biofilm viability by 86.5%, substantially outperforming spent hop extract (42.8%), and achieved near-complete eradication (97–99%) at higher doses [

41]. XN also displayed meaningful activity against

enterococci, with MIC values of 7.5 mg/L and efficacy extending to vancomycin-resistant

E. faecium [

40].

Representative antibacterial, antiparasitic, and antifungal activities of XN across diverse pathogens, including Gram-positive bacteria, biofilm-forming communities, parasites, and fungi, are summarized in

Table 3.

Several mechanisms underlie XN’s antimicrobial effects. XN disrupts cell membrane integrity, interferes with fatty acid metabolism, and promotes intracellular proton accumulation leading to metabolic starvation [

38,

39]. Its hydrophobic structure facilitates penetration of bacterial cell walls and incorporation into inner membranes, where XN functions as a mobile carrier ionophore. This activity drives electroneutral proton influx, inhibits active transport systems, and ultimately limits the uptake of essential sugars and amino acids [

39].

Anti-biofilm: In multispecies biofilm models designed to simulate oral peri-implant conditions, XN at 100 μM exhibited striking antimicrobial activity against six bacterial species associated with peri-implantitis, showing inhibition rates ranging from 95.90% to 99.20% [

42]. XN-treated biofilms displayed markedly reduced biomass and cell viability and, in several cases, achieved greater reductions than chlorhexidine. Structural disruption of the biofilms included architectural degradation. These findings highlight XN’s strong potential as an anti-biofilm agent in oral infectious disease settings [

42].

Mechanistically, XN exerts activity against biofilm-forming bacteria by targeting lipid metabolism, resulting in altered cell wall hydrophobicity and impaired adhesion. XN also disrupts quorum-sensing pathways essential for microbial communication and coordinated biofilm formation [

43]. XN acts as a diacylglycerol acyltransferase inhibitor [

43], destabilizing bacterial membranes by interfering with lipid synthesis and cell wall integrity. Together, these mechanisms position XN as a multifaceted antimicrobial agent capable of targeting both planktonic and biofilm-embedded pathogens.

Anti-coronavirus: XN exhibits potent antiviral activity across multiple coronaviruses, as summarized in

Table 4, through direct inhibition of the viral main protease (Mpro), a pivotal enzyme required for viral replication [

44]. Pretreatment with XN restricted viral replication in Vero-E6 cells [

44]. XN achieved an IC

50 of 1.53 μM against SARS-CoV-2 and an IC

50 of 7.51 μM for alphacoronavirus PEDV [

44]. XN displays strong antiviral effects against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Treatment with XN (5–15 μM) produced dose-dependent decreases in virus titers and viral mRNA levels with a selectivity index greater than 10 [

45]. XN blocked PRRSV entry and internalization into cells and exerted its antiviral effects partially through activation of the Nrf2-HMOX1 antioxidant pathway, leading to increased expression of Nrf2, HMOX1, GCLC, GCLM, and NQO1, a dual mechanism blocking viral entry and enhancing cellular antioxidant defenses [

45].

Anti-HCV: XN demonstrated dose-dependent activity of anti-HCV replicons [

46]. At concentrations of 7.05–14.11 μM, XN achieved inhibitory effects comparable to interferon-alpha 2b, producing similar reductions in HCV RNA levels [

46]. In the bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) surrogate model of HCV, XN exhibited EC 50 values of 2.77–3.24 mg/L, with therapeutic indices exceeding 7.72–9.03 [

47]. XN suppressed BVDV E2 expression and viral RNA in a dose-dependent manner. Comparatively, XN showed stronger inhibitory activity than ribavirin but was less potent than interferon-alpha [

47]. In vivo, using the

Tupaia belangeri model infected with HCV-positive serum, XN significantly reduced serum aminotransferases, histological activity scores, hepatic steatosis, and hepatic TGF-β1 expression, demonstrating both antiviral and hepatoprotective effects [

48].

Anti-HIV-1, anti-HSV, and other viruses: XN exhibits anti-HIV-1 activity. In C8166 lymphocytes, XN achieved a therapeutic index of approximately 10.8 by suppressing virus-induced cytopathic effects, with an EC50 value of 0.82 μg/mL, reducing viral p24 antigen production at 1.28 μg/mL and inhibiting reverse transcriptase activity at 0.50 μg/mL [

49]. In peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), the EC50 was higher (20.74 μg/mL), reflecting cell-type-dependent sensitivity. Notably, XN did not inhibit recombinant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase activity or viral entry directly [

49], indicating that its antiviral effects may involve alternative host- or virus-directed mechanisms that remain to be elucidated.

A XN-enriched hop extract (with >99% purity of XN) demonstrated low-to-moderate antiviral activity against multiple DNA and RNA viruses [

50]. XN was more potent than isoxanthohumol against HSV-1 and HSV-2, with therapeutic indices of >1.9 and >5.3 respectively. Conversely, isoxanthohumol showed superior activity against CMV. XN exhibited a therapeutic index of 4.0 against rhinovirus [

50].

XN also shows promise against arboviruses. For Oropouche virus (OROV), a member of

Peribunyaviridae, XN demonstrated inhibitory activity with an EC50 of 50.2 μg/mL and a selectivity index of 4.9 [

51]. Computational docking and biochemical analyses identified interactions between XN and residues Lys92 and Arg33 of the OROV endonuclease domain, an essential component of cap-snatching viral transcription [

51].

Antiparasitic and antifungal effects: XN demonstrates substantial antiparasitic activity across multiple species [

52]. XN exhibited the strongest antiplasmodial effect among eight tested chalcone derivatives, with IC

50 values of 8.2 ± 0.3 μM for the chloroquine-sensitive poW strain and 24.0 ± 0.8 μM for the multidrug-resistant Dd2 clone [

52]. Several chalcones, including XN, were shown to interfere with glutathione-dependent hemin degradation, a vital metabolic process for

P. falciparum survival [

52].

XN inhibits

Eimeria species associated with coccidiosis. At 22 ppm, XN reduced

E. tenella sporozoite invasion of MDBK cells by 66%, with physical disruption of parasite apical structures [

53]. In vivo chick models demonstrated that pretreatment of

E. tenella and

E. acervulina sporozoites with 5–20 ppm XN reduced gross lesion scores and resulted in either normal weight gains or reduced oocyst shedding [

53]. XN displayed inhibitory activity against

Babesia microti with an IC

50 of 21.40 μM and a selectivity index > 4.7 [

54]. XN (50 μM) reduced parasitemia in infected erythrocytes to 2.07%, exhibiting similar effects of diminazene aceturate [

54].

XN exhibits broad antifungal activity against

Candida albicans, such as

C. krusei,

C. tropicalis, and

C. parapsilosis [

55]. In multispecies biofilm models, XN inhibited filamentous growth of

C. albicans and partially reversed the disruptive effects of fungal overgrowth on periodontopathogenic bacteria. XN suppressed biomass and cell viability in biofilms [

42,

55].

3.2. Selectivity and Safety Profile

The therapeutic windows of XN varied across pathogens and study designs. For example, the therapeutic index was about 10.8 against HIV-1 [

49], 7.72–9.03 against BVDV as an HCV surrogate [

47], >5.3 against HSV-2, 4.0 against rhinovirus [

50], >10 against PRRSV [

45], and about 4.9 for OROV [

51]. A comparative overview of antiviral selectivity indices and nutraceutical windows is provided in

Table 4.

Hop derivatives demonstrated low cytotoxicity and low absorption [

39]. In tuberculosis studies, oral administration of XN at various doses proved safe, with no significant changes in biochemical parameters or liver indices compared to control groups [

56]. One notable safety consideration emerged in biofilm studies, where XN may have exhibited cytotoxic effects at concentrations above 100 μM [

42,

55], although such levels are typically higher than those required for antimicrobial or antiparasitic activity. Importantly, XN has shown hepatoprotective properties when co-administered with isoniazid during tuberculosis treatment. The combination reduced drug-induced liver injury, as evidenced by decreases in ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin, and MDA, along with increases in SOD, GSH-Px, and ATPases. This protective effect operated through activation of antioxidative defense systems and protection of hepatocellular membranes [

56]. Together, these findings indicate that XN possesses a favorable safety profile and may provide added protective benefits in combination therapeutic settings.

3.3. Comparative Effectiveness with Standard Treatments

XN frequently demonstrates antimicrobial and antiviral potency comparable to, or exceeding, several standard treatments. Against

C. difficile and

Staphylococcus aureus, XN’s MIC/MBC values approach those of conventional antibiotics. XN also outperformed other hop-derived compounds, including lupulone, humulone [

40], α- and β-bitter acids, and commercial extracts [

39], across multiple studies. Methanolic extracts enriched in XN were markedly more active than essential oils, and antimicrobial performance correlated strongly with XN content rather than α-acid concentration [

57]. Synergistic interactions were observed when XN was combined with standard antibiotics, enhancing the activity of oxacillin against MSSA and linezolid against both MSSA and MRSA [

41]. In tuberculosis models, XN combined with isoniazid produced the lowest lung and spleen colony-forming unit counts compared to all other treatment groups [

56]. XN plus isoniazid outperformed isoniazid monotherapy in both antibacterial efficacy and hepatoprotective activity [

56].

In biofilm models, XN showed a mixed but notable performance relative to chlorhexidine, achieving higher reductions for some bacterial species and performing slightly below curcumin for most [

42,

55]. Pure XN exhibited strong biofilm-eradicating capacity, reducing viability by 86.5% at MIC and approaching near-complete eradication at higher concentrations [

41]. However, in staphylococcal biofilm assays, lupulone showed the strongest effect at high concentrations, followed closely by XN, with both achieving complete eradication at elevated doses [

41].

Relative to antiviral standards, XN achieved inhibitory effects comparable to interferon-α2b in HCV replicon systems and displayed greater potency than ribavirin but less than interferon-α in the BVDV surrogate model [

46,

47]. Synergy with interferon-α has also been observed against HCV. A combination of 3.13 μg/mL XN with 50 IU/mL IFN-α yielded greater inhibitory effects on viral RNA levels than either agent alone at higher concentrations (6.25 μg/mL XN or 100 IU/mL IFN-α) [

58].

Table 3.

Antimicrobial and antifungal effects of xanthohumol.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial and antifungal effects of xanthohumol.

| Pathogen Group | Species/Strain (Model) | Concentration | Mechanism Highlights | Ref. |

|---|

| Oral biofilm (Gram+) | S. oralis, A. naeslundii, V. parvula | 100 µM | Biofilm viability/biomass ↓ | [42] |

| Oral biofilm (Gram− mix) | F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans | 100 µM | Biofilm viability/biomass ↓ | [42] |

| Oral biofilm (mixed) | F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans | N.A. | Candida–bacteria community structure normalized | [55] |

| Parasite (malaria, CQ-sens.) | P. falciparum (poW) | IC50 = 8.2 ± 0.3 µM | Interference with hemin detox | [52] |

| Parasite (malaria, MDR) | P. falciparum (Dd2) | IC50 = 24.0 ± 0.8 µM | Interference with hemin detox | [52] |

| Parasite (coccidia) | E. tenella (MDBK invasion) | 22 ppm | Physical disruption of apical ends | [53] |

| Parasite (coccidia) | E. acervulina | 5–20 ppm | Anti-invasion effects | [53] |

| Parasite (babesiosis) | Babesia microti | IC50 = 21.40 µM | Likely mitochondrial/ROS modulation | [54] |

| Fungi (Candida spp.) | C. albicans, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis | N.A. | N.A. | [40] |

| Fungi–bacteria biofilm | C. albicans within mixed biofilm | N.A. | Biofilm structure & vitality normalized | [55] |

Table 4.

Antiviral effects of xanthohumol.

Table 4.

Antiviral effects of xanthohumol.

| Virus | System (Cell/Animal) | XN Dose/EC50/IC50 | Selectivity Index | Primary Readouts | Ref. |

|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Vero-E6; Mpro enzyme | IC50 (Mpro) = 1.53 µM | N.A. | Replication restricted in Vero-E6 | [44] |

| PEDV (alpha-CoV) | Cell culture | IC50 = 7.51 µM | N.A. | Replication restricted | [44] |

| PRRSV (BB0907, S1, FJ1402) | Marc-145 & porcine alveolar macrophages | 5–15 µM | SI > 10 | Dose-dependent ↓ titers and mRNA | [45] |

| HCV replicon | Huh7.5 replicon | 3.53–14.11 µM | N.A. | Luciferase & RNA ↓; effects ≈ IFN-α at 7.05–14.11 µM | [46] |

| HCV surrogate (BVDV) | MDBK | EC50 = 2.77–3.24 mg/L | TI > 7.72–9.03 | CPE, E2, RNA ↓ (2.88–3.83 log10) | [47] |

| HCV surrogate (BVDV) | MDBK | 3.13 µg/mL XN + 50 IU/mL IFN-α | N.A. | Viral RNA ↓ greater than either alone | [58] |

| HCV in vivo | Tupaia model (HCV-positive serum) | N.A. | N.A. | ↓ aminotransferases, steatosis, histological activity index | [48] |

| HIV-1 | C8166; PBMCs | EC50 = 0.50–1.28 µg/mL (C8166); 20.74 µg/mL (PBMCs) | ~10.8 (C8166) | p24 & RT production ↓ | [49] |

| Broad panel (BVDV, HSV-1/2, CMV, RV) | Cell culture | Low µg/mL range | HSV-2 TI > 5.3; RV TI = 4.0; CMV TI ≈ 4.2 (iso-α-acids) | CPE ↓ | [50] |

| Oropouche virus (OROV) | Cell culture & in silico analysis | EC50 = 50.2 µg/mL | SI = 4.9 | Replication ↓ | [51] |

4. Neuroprotective and Neuromodulatory Effects

XN demonstrates broad neuroprotective effects across acute neurological injuries, chronic neurodegenerative diseases, and psychiatric conditions. These benefits arise through multiple complementary mechanisms, including Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defenses, inhibition of NF-κB signaling, prevention of apoptosis, enhancement of autophagy, and modulation of gut–brain axis pathways.

4.1. Neuroprotective Effects Across Neurological Conditions

Acute Neuroprotection: In middle cerebral artery occlusion-mediated cerebral ischemia models, administration of XN (0.2 or 0.4 mg/kg) 10 min before injury produced dose-dependent neuroprotection, exhibiting a reduction in infarct volume and improvement of neurological function [

59]. These benefits were accompanied by suppressed expression of inflammatory proteins, including hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, tumor necrosis factor-α, phosphorylation of p38, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and active caspase-3 [

59,

60]. A comparative summary of neurological condition-specific models, XN regimens, functional outcomes, and associated biomarker changes is provided in

Table 5.

In intracerebral hemorrhage, XN improved neurologic scores and reduced brain edema at 24 h post-injury. It attenuated neuronal apoptosis and decreased expression of pro-inflammatory mediators; effects were mediated through suppression of p65 phosphorylation in brain tissue [

61]. In kainic acid-induced excitotoxic injury, pretreatment with XN (10 or 50 mg/kg) markedly reduced seizure severity, prevented excessive glutamate elevation, and protected CA3 hippocampal neurons. Mechanistically, XN restored levels of the mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn-2 and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, while inhibiting Apaf-1 expression and caspase-3 activation [

62].

XN also showed protection against light-induced retinal degeneration. XN with doses of 0.4 and 0.8 mg/kg preserved visual acuity by approximately 50% and maintained 30% to 90% of photoreceptor function [

63]. Histological analyses showed preservation of outer nuclear layer cell counts and reductions in apoptotic cells. XN further stabilized glutathione disulfide and cystine redox potentials, supporting its role in antioxidant defense [

63].

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Models: XN demonstrates broad and consistent neuroprotective activity across multiple AD cellular and animal models. In N2a/APP cells, XN at 0.75–3.0 μM reduced accumulation of Aβ

1–42 and Aβ

1–40 and lowered their ratio. It also ameliorated tau hyperphosphorylation at Ser404, Ser396, and Ser262 through modulation of PP2A and GSK3β signaling. Proteomic analysis identified 30 differentially expressed proteins affected by XN, spanning pathways involved in ER stress, oxidative stress, proteasome function, and cytoskeletal organization [

64].

In APP/PS1 transgenic mice, XN treatment for two months improved spatial learning and memory, evidenced by reduced latency and increased time spent in the Morris water maze target quadrant [

65]. These behavioral benefits corresponded to reduced hippocampal Aβ deposition, increased superoxide dismutase levels, and decreased IL-6 and IL-1β in both serum and the hippocampus. Mechanistic analyses showed activation of autophagy (mTOR/LC3) and anti-apoptotic (Bax/Bcl-2) pathways [

65]. XN enhanced ATP synthesis and mitophagy in the young AD hippocampus [

66].

Dose–response differences were observed in another APP/PS1 study: XN (0.5 mg/kg) altered 108 hippocampal proteins, whereas a dose of 5 mg/kg altered only 72, suggesting greater responses at lower doses [

67]. XN improved spatial learning and memory, enhanced newborn neurons in the subgranular zone and dentate gyrus, and decreased inflammatory responses [

68]. Importantly, XN (5 mg/kg every other day for 90 days) reshaped gut microbiota in both prevention (2-month-old) and therapeutic (6-month-old) settings, modulating taxa such as Gammaproteobacteria, Nodosilineaceae, and Rikenellaceae, and influencing metabolic pathways related to penicillin/cephalosporin biosynthesis and atrazine degradation [

68,

69].

XN improved AD-related metabolic and cognitive outcomes in high-fat diet models. Dietary XN (0.07%, ~60 mg/kg/day) elicited sex- and ApoE-dependent improvements in learning and memory and increased hippocampal and cortical expression of glucose transporters, with elevation of Glut1 and Glut3. XN elevated diacylglycerol and sphingomyelin levels in females but decreased them in males, with lipid signatures correlating with improved cognitive performance [

70,

71].

Depression and Stress-Related Disorders: XN exhibits antidepressant and neuroprotective effects in models of depression and stress-induced neurological dysfunction. In the chronic unpredictable mild stress model, XN (20 mg/kg) alleviated depressive-like behaviors and increased synaptic protein expression in the medial prefrontal cortex. Treatment also reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress [

72]. XN also protected primary cortical neurons from corticosterone-induced cytotoxicity in stress-like disorders by preventing cell viability loss and preserving neuronal and astrocytic populations [

73]. It restored brain-derived neurotrophic factor (

Bdnf) mRNA levels, and its neuroprotective effects were abolished by Nrf2 inhibition, highlighting Nrf2 as a critical mediator specific to XN, in contrast to quercetin, which modulated Fkbp5 [

73].

Pain Syndromes: XN demonstrates analgesic and anti-inflammatory efficacy in models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain [

74]. In chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain, XN reversed reductions in thermal withdrawal latency and mechanical withdrawal thresholds [

75]. These behavioral improvements were accompanied by suppressed spinal cord production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, along with reduced phosphorylation of ERK and NF-κB p65 [

75].

In collagen-induced arthritis, XN administered intraperitoneally for three days reduced spontaneous pain behaviors, increased mechanical pain thresholds, and prolonged withdrawal latency [

75]. Mechanistically, XN diminished the NLRP3 inflammasome in the spinal cord, enhanced Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses, and lowered mitochondrial ROS production. Structural and biochemical analyses further demonstrated that XN binds to AMPK via two electrovalent bonds and increases its phosphorylation at Thr174, identifying AMPK activation as a key contributor to XN’s analgesic effects [

75].

Other Neurological Conditions: XN demonstrates neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing effects across several neurological and aging-related models. In ovariectomy-induced cognitive decline models, XN reversed deficits in the Morris water maze and open field tests. Mechanistically, XN suppressed the injury-associated increase in miR-532-3p and restored expression of its downstream target

Mpped1 in the hippocampus. Functional studies confirmed that the 3′UTR of

Mpped1 is directly regulated by miR-532-3p. Overexpression of Mpped1 in the hippocampus relieved cognitive impairment, demonstrating a causal relationship [

76].

In iron overload-induced nerve injury, both hops extract and XN improved memory performance, reflected by shortened escape latency, increased platform crossings, and improved spontaneous alternation ratios. XN treatment elevated hippocampal antioxidant enzymes (SOD and GSH-Px) and lowered lipid peroxidation markers (MDA), while reducing ROS levels in PC12 cells exposed to iron dextran [

77].

In an epilepsy model, pretreatment with oral XN (20 mg/kg) reduced pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced seizure onset and duration, mortality, and behavioral abnormalities [

78]. XN decreased neuroinflammatory mediators (COX-2, TNF-α, NF-κB, TLR-4, and IL-1β) and oxidative stress markers (MDA and NO), while increasing GSH and SOD (

p < 0.05). It also lowered glutamate levels and improved dopamine, GABA, Na

+/K

+-ATPase, and Ca

2+-ATPase activities. Histopathology confirmed reduced inflammation and neuronal pyknosis [

78].

In aging SAMP8 mice, chronic XN treatment reduced brain levels of IL-2, TNF-α, and IL-6, and blunted age-related increases in TNF-α, IL-1β, HO-1, iNOS, and GFAP expression [

79]. XN counteracted synaptic decline by restoring mature BDNF and reducing pro-BDNF levels and increased the synaptic markers synapsin-I and synaptophysin [

79].

4.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroprotection

XN exerts neuroprotection through multiple convergent mechanisms that vary across neurological conditions but consistently involve antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, synaptic, metabolic, and regulatory pathways. The major neuroprotective pathways engaged by XN in neural systems, together with linked functional outcomes and behavioral assays, are summarized in

Table 6.

Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defense (core mechanism): XN robustly activates the Nrf2 pathway across models of depression, pain, ischemia, excitotoxicity, and iron overload [

59,

77]. It increases expression of HO-1, NQO1, SOD, and related antioxidant enzymes; reduces mitochondrial ROS; and prevents oxidative–nitrosative stress. Causal evidence comes from studies where Nrf2 inhibition blocks XN-mediated protection [

73]. Consistent Nrf2 engagement across depression, retina, and oxidative injury paradigms is reflected in

Table 6.

Anti-inflammatory signaling: XN suppresses several inflammatory cascades, including the NF-κB, NLRP3, p38-MAPK, ERK, and TLR4 pathways [

59,

61,

72,

75]. This results in broad reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 across multiple disease models [

65,

75].

Anti-apoptotic and autophagic regulation: XN modulates Bax/Bcl-2 ratios, activates mTOR/LC3-dependent autophagy, and prevents caspase activation. In excitotoxicity and AD models, XN preserves mitochondrial integrity through upregulation of Mfn-2 and Bcl-2 and suppression of Apaf-1 and cleaved caspase-3 [

62,

65].

Tau and kinase pathway regulation: In AD models, XN reduces tau hyperphosphorylation by regulating PP2A and GSK3β signaling [

64]. In iron overload models, XN activates AKT/GSK3β, further supporting neuroprotection [

77].

Synaptic and neurotransmission modulation: XN normalizes excessive postsynaptic glutamate receptor expression in APP/PS1 mice [

68]. In synaptosomes, it inhibits 4-aminopyridine-evoked glutamate release by reducing Ca

2+ influx through N- and P/Q-type channels and suppressing Ca

2+/calmodulin-PKA signaling via GABAa receptor engagement [

80].

Energy metabolism and AMPK activation: XN improves metabolic resilience by activating AMPK (via direct binding and Thr174 phosphorylation) [

75], enhancing ATP synthesis and mitophagy [

68], and increasing Glut1/Glut3 expression in the hippocampus and cortex [

70,

71].

Gut–brain axis modulation: XN reshapes gut microbiota composition, modulates taxa, and alters microbial metabolic pathways in both preventive and therapeutic AD models [

68,

69]. It also correlates gut microbiome changes with hippocampal proteomics [

67].

miRNA regulation: XN regulates disease-associated miRNAs, for example, suppressing miR-532-3p and restoring its target Mpped1 to improve cognition in ovariectomy-induced decline [

76].

Adenosine pathway modulation: XN increases adenosine A1 receptor levels and decreases CD73 activity [

81], potentially reducing excitotoxicity in conjunction with its glutamate-modulatory effects [

62,

80].

4.3. Translational Considerations and Study Limitations

Across neurological models, XN displayed clear dose-dependent neuroprotective patterns. Timing was a critical determinant of efficacy. Pre-injury dosing produced the most consistent protection: 10 min before ischemia [

59], 30 min before excitotoxic seizures [

62], and 30 min before PTZ-induced epilepsy [

78]. For degenerative processes, chronic administration was essential, with benefits emerging after weeks to months of treatment. The diversity of dosing regimens and temporal windows across neurological models is summarized in

Table 5.

Several studies identified limitations relevant to advancing XN toward clinical use. Bioavailability and delivery challenges were repeatedly noted. Retinal degeneration studies emphasized that effective neuroprotective concentrations cannot be achieved through dietary (beer) consumption and require dedicated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic optimization [

63]. In microbiome-modulating AD studies, oral absorption of XN may have been suboptimal, potentially reducing effect sizes [

69], and treatment durations may not have been long enough to capture late-stage cognitive decline in APP/PS1 mice [

68]. Several studies acknowledged important limitations and translational challenges. In light-induced retinal degeneration studies, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies were identified as necessary to understand how XN is transported into the retina. The authors noted that achieving neuroprotective plasma concentrations through beer consumption is unlikely, highlighting the need for alternative delivery methods. Further experiments were needed to verify the mechanism of XN’s antioxidant response [

63].

The limitations related to methodologies and model systems included: reliance on behavioral readouts without neuropathological confirmation [

68], limited resolution of 16S rDNA sequencing for microbiome analysis [

69], and the inherent reductionism of in vitro AD models [

64]. High-fat diet studies revealed ApoE isoform- and sex-specific responses, limiting generalizability and emphasizing the need to model diverse populations [

70,

71]. Age also influenced responsiveness, with reduced efficacy observed in older animals [

71]. In corticosterone-induced cytotoxicity, gaps remain in understanding polyphenol neuroprotection pathways [

73]. Age-related cognitive studies also revealed confounds such as poor performance in young mice due to phytoestrogen-deficient diets and limited efficacy in older animals [

82]. In adenosine pathway studies, discrepancies between gene and protein expression suggested methodological or timing-related limitations [

81].

Table 5.

Neuroprotective effects of xanthohumol.

Table 5.

Neuroprotective effects of xanthohumol.

| Condition/Model | Species/Cell Line | Xanthohumol Regimen | Key Functional Outcomes | Key Biomarkers/Readouts | Refs. |

|---|

| Cerebral ischemia (MCAO) | Rat MCAO | 0.2–0.4 mg/kg; −10 min pre-occlusion | ↓ infarct size; improved neuro scores | ↓ HIF-1α, TNF-α, iNOS; ↓ active caspase-3; ↓ p-P38 and ↑ Nrf2 | [59,60] |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | Rat ICH | Peri-injury dosing (per paper) | ↑ neurologic scores; ↓ brain edema | ↓ p65-P; ↓ apoptosis; ↓ inflammatory mediators | [61] |

| Excitotoxicity (kainate) | Rat (KA) | 10 or 50 mg/kg, −30 min | Seizures ameliorated; CA3 neuron protection | ↑ Mfn-2, Bcl-2; ↓ Apaf-1, cleaved caspase-3; ↓ glutamate | [62] |

| Retinal degeneration (light-induced) | Mouse | 0.4–0.8 mg/kg; −1 d, −1 h, then q3d | ~50% VA preserved; 30–90% PR function retained | ↓ TUNEL+; ONL nuclei preserved; redox homeostasis | [63] |

| AD cell model (N2a/APPswe) | Neuro2a/APPswe | 0.75–3.0 µM | ↓ Aβ1-42/1-40; ↓ Aβ ratio | ↓ tau pS404/pS396/pS262 via PP2A & GSK3β | [64] |

| AD transgenic (APP/PS1) | Mouse APP/PS1 | 30–90 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, 6 d/week × 2 months | MWM: ↓ latency; ↑ target time | ↓ hippocampal Aβ; ↑ SOD; ↓ IL-6/IL-1β; ↑ mTOR/LC3; Bax/Bcl-2 shift | [65] |

| AD transgenic (microbiome–therapy/prevention) | Mouse APP/PS1 | 5 mg/kg qod ×90 d | Cognitive protection; prevention vs. therapy differences | ATP↑; mitophagy↑; blood/intestine glutamate↓ | [69] |

| AD transgenic (dose–proteome) | Mouse APP/PS1 | 0.5 vs. 5 mg/kg | 0.5 mg/kg: 108 proteins altered vs. 72 at 5 mg/kg | Broader hippocampal proteome shift at lower dose | [67] |

| Diet-induced cognitive impairment | WT & FXR intestine-KO mice; ApoE stratified | 0.07% diet (~60 mg/kg/d), 10–19 weeks | Learning/memory improved (sex- & ApoE isoform-dependent) | ↑ Glut1, ↑ Glut3; lipidome shifts | [71] |

| Chronic stress-induced depression (CUMS) | Mouse | 20 mg/kg oral gavage | Depressive-like behavior ↓; synaptic proteins ↑ | ↑ Sirt1; ↓ NF-κB/NLRP3; ↑ Nrf2/HO-1 | [72] |

| Corticosterone toxicity | Primary cortical cells | 0.2–5 µM XN, 24 h pretreatment + 200 µM CORT × 96 h | Viability rescued; neuron/astrocyte balance | Nrf2-dependent; BDNF mRNA restored | [73] |

| Neuropathic pain (CCI) | Rat CCI | 10–40 mg/kg XN, i.p., once daily × 10 days (starting day 1 post-CCI) | ↑ thermal/mech thresholds | ↓ TNF-α/IL-1β; ↓ p-ERK & NF-κB p65 | [74] |

| Arthritis pain (CIA) | Mouse CIA | 3-day i.p. | ↓ flinches; ↑ thresholds; ↑ latency | ↓ NLRP3; ↑ Nrf2; mito-ROS↓; AMPK binding; p-AMPK(Thr174) ↑ | [75] |

| Ovariectomy-associated cognitive decline | OVX mice | 30–60 mg/kg/day XN, oral gavage × 8 weeks | MWM/open field improved | miR-532-3p↓; Mpped1↑ (validated 3′UTR) | [76] |

| Iron overload injury | PC12; mouse | 1–10 µM (PC12, 24 h pretreat); 10 mg/kg/day p.o. × 4 weeks (mouse) | Memory improved; ROS↓ | AKT/GSK3β & Nrf2/NQO1 activation | [77] |

| Epilepsy (PTZ) | Mouse PTZ | 20 mg/kg, −30 min | ↓ onset/duration; ↓ mortality | ↓ COX-2, TNF-α, NF-κB, TLR-4, IL-1β; ↓ MDA/NO; ↑ GSH/SOD; NTs normalized | [78] |

Table 6.

Molecular mechanisms underlying xanthohumol’s neuroprotection.

Table 6.

Molecular mechanisms underlying xanthohumol’s neuroprotection.

| Pathway/Process | Mechanistic Modulations | Linked Functional Outcome | Behavioral Assays | References |

|---|

| Nrf2 antioxidant axis | ↑ Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1/SOD; Nrf2 inhibitor blocks protection in cortical cells | Antioxidant defense; survival ↑ | Depression tests; VA/ERG (retina) | [63,72,77] |

| NF-κB inflammatory signaling | ↓ p-NF-κB/p65; cytokines ↓ | Neuroinflammation ↓; behavior improved | Neuro scores; depression tests | [61,72] |

| NLRP3 inflammasome | NLRP3 markers ↓ (spinal cord/mPFC) | Analgesia; antidepressant-like effects | Pain batteries; CUMS | [72,75] |

| Autophagy/apoptosis (mTOR/LC3; Bax/Bcl-2) | Autophagy ↑; Bax/Bcl-2 shift | Cognitive rescue; Aβ↓ | Morris water maze | [65] |

| Mitochondrial integrity | ↑ Mfn-2 & Bcl-2; ↓ Apaf-1, caspase-3 | Seizure protection | Seizure severity | [66] |

| Tau/kinase regulation | ↓ tau pS404/396/262 via PP2A & GSK3β | AD pathology ↓ | N/A | [64] |

| Synaptic glutamate release | Presynaptic GABA_A-dependent ↓ Ca2+ influx → CaM/PKA ↓ → glutamate release ↓ | Anti-excitotoxic | N/A (synaptosomes) | [80] |

| AMPK/energy | AMPK binding & Thr174↑; Glut1/3↑; ATP, mitophagy↑ | Analgesia; cognition ↑ | Learning tasks; pain assays | [67,69,71,75] |

| Gut–brain axis | Microbiota composition shifts; proteome–microbiome correlation reversal at 0.5 mg/kg | Prevention-phase cognitive benefits | Learning/memory | [67,69] |

| miRNA regulation | miR-532-3p↓; Mpped1↑; validated 3′UTR | OVX cognition improved | Morris water maze; open field | [76] |

5. Cardiovascular Effects of Xanthohumol

XN exhibits multiple cardioprotective actions through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, metabolic, and endothelial-regulatory mechanisms. XN enhances Nrf2-dependent antioxidant defenses, reduces oxidative stress, and attenuates inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB, contributing to protection against ischemia–reperfusion injury and endothelial dysfunction. It improves vascular tone by enhancing nitric oxide bioavailability, suppressing inducible nitric oxide synthase, and reducing reactive oxygen species, thereby supporting healthier endothelial function. An excellent review regarding XN’s cardiometabolic effects has been made available [

83]. In this section, we focus on XN’s effects on endothelial functions.

5.1. Functional Cardiovascular Effects of XN

Anti-angiogenic effects: XN showed anti-angiogenic activity in various in vitro and in vivo models [

24,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. Using human HUVECs, XN reduced capillary-like structure formation on Matrigel and suppressed angiogenic signaling in vitro [

24,

84,

85,

89]. In vivo, reduced microvessel density and vascularization were observed in tumor xenograft and endometriosis models [

24,

86,

87]. The magnitude of anti-angiogenic effects showed a dose-dependent pattern, with significant effects observed at concentrations as low as 5–10 micromolar [

84,

85,

88].

Cellular viability and apoptosis: XN inhibited proliferations of endothelial cell and vascular smooth muscle cell [

84,

85,

90,

91]. XN could induce apoptosis with higher concentrations (10 micromolar) or prolonged exposure [

84,

85].

Migration and invasion inhibition: XN robustly inhibited migration and invasion of endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, as assessed by wound healing, Boyden chamber, and transwell assays [

84,

85,

88,

90,

91]. Effects of XN against inflammation were observed both in the presence and absence of pro-inflammatory stimuli such as tumor necrosis factor alpha [

24,

88]. These inhibitory effects were dose- and time-dependent [

84,

85].

Endothelial barrier protection: XN was reported to attenuate tumor cell-mediated defects in the lymph endothelial barrier, reducing circular chemorepellent-induced defect (CCID) formation and suppressing adhesion molecule expression, showing a protective effect on endothelial integrity in the context of metastasis [

92].

Inhibition of vascular calcification: In a rat model of vascular calcification induced by vitamin D3 and nicotine, XN reduced calcium deposition and alkaline phosphatase activity in calcified arteries. XN also decreased oxidative stress markers and improved arterial structure, while suppressing osteogenic transcription factors (BMP-2, Runx2) and preserving the vascular smooth muscle phenotype through upregulation of the Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 antioxidant pathway [

93].

Cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis: Evidence indicates that XN attenuates pathological cardiac remodeling. In cardiac fibroblasts stimulated by TGF-β1, XN inhibits proliferation, differentiation, and collagen overproduction via modulation of the PTEN/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, pointing to potential protection against fibrosis common in heart failure and hypertensive heart disease [

2]. A consolidated summary of XN’s effects on endothelial angiogenesis, proliferation, migration, invasion, and barrier integrity across experimental models is presented in

Table 7.

5.2. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Cardiovascular Effects

Inhibition of NF-κB pathway: NF-κB inhibition is consistently observed across models of angiogenesis, migration and invasion, and endothelial barrier dysfunction [

84,

88,

92]. This was demonstrated by reduced NF-κB activity, decreased expression of NF-κB target genes (such as adhesion molecules and cytokines), and suppression of downstream inflammatory and angiogenic responses [

84,

88,

92].

Repression of Akt signaling: XN repressed Akt signaling, leading to decreased phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream targets, contributing to a reduction in cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenic capacity [

84].

Activation of AMPK: XN was found to activate AMP-activated protein kinase in endothelial cells, mediated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta (CaMKKβ), resulting in decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation and nitric oxide (NO) production [

85]. These coordinated effects on metabolic and inflammatory signaling nodes are reflected in

Table 8.

Other mechanisms: XN also downregulates epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, supporting its ability to inhibit migration, invasion, and barrier disruption [

88,

92]. Additional reported mechanisms include suppression of PI3K/Akt-associated signaling, cell cycle arrest, induction of apoptosis, suppression of VEGF, and downregulation of ICAM-1 across various cellular contexts [

83,

84,

85,

86,

88,

90,

92].

Collectively, these findings highlight XN’s capacity to modulate multiple pro-pathogenic signaling networks central to vascular remodeling and cellular dysfunction. An integrated overview of these signaling pathways and their functional consequences is provided in

Table 8.

6. Hepatic and Hepato-Renal Protections

XN provides hepatoprotection across diverse liver injury models through activations of AMPK and Nrf2 and inhibition of NFκB, which coordinately reduce oxidative stress, suppress inflammation, regulate apoptosis, and prevent fibrosis.

6.1. Protection Across Liver Injury Models

In HFD-induced NAFLD, XN attenuated weight gain, improved glucose and insulin tolerance, and reduced hepatic lipid accumulation [

94]. In CCl4-induced injury, XN significantly reduced liver weight, normalized plasma enzyme activities, and prevented histopathological alterations [

95]. In acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity, XN could reduce mortality, ameliorate transaminase elevation, prevent glutathione depletion, and suppress lipid peroxidation [

5,

96]. XN demonstrated selective protection in the ischemia–reperfusion model. It showed inhibition of oxidative stress and almost completely blunted inflammatory responses [

97]. XN showed significant reductions in aminotransferase levels, histological activity indices, and hepatic steatosis scores in an HCV-infected liver model. However, the reduction in HCV core protein expression was limited [

98], suggesting that the protective effects were mediated primarily through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms rather than direct antiviral activity. A comparative overview of liver injury models, XN dosing regimens, protective outcomes, and associated mechanisms is summarized in

Table 9.

Several studies explicitly reported that XN’s hepatoprotection showed dose–response relationships. In vitro, XN showed dose-dependent inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation between 0 and 20 μM, with no impairment of hepatocyte viability even at 50 μM [

99,

100]. This selective targeting of stellate cells versus hepatocytes suggests a favorable therapeutic window. In the aging model, effects were dose-dependent in most cases when comparing 1 versus 5 mg/kg/day [

101]. The ethanol-induced liver damage model also demonstrated dose-dependent protection across multiple tissues [

102].

6.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Hepatoprotection

Three major signaling pathways have been shown to be related to XN’s hepatoprotective mechanisms. The major molecular pathways underlying these hepatoprotective and metabolic effects are summarized in

Table 10. AMPK activation emerged as a critical pathway, as shown, that increased AMPK phosphorylation (Thr72) and mRNA expression, which mediated the anti-steatotic effects [

94]. Co-treatment with compound C, an AMPK inhibitor, completely abolished all protective effects mediated by XN. AMPK activation subsequently reduced expression of the lipogenic genes SREBP1c and ACC-1 [

94].

Nrf2 activation represents another major mechanism. XN increased Nrf2 nuclear accumulation or transcription [

5,

94,

96]. XN could covalently modify Keap1 [

103], the negative regulator of Nrf2, thereby activating the Nrf2/xCT/GPX4 signaling pathway [

98]. XN could also activate Nrf2 through the AMPK/Akt/GSK3β pathway [

96], revealing crosstalk between AMPK and Nrf2 signaling.

NFκB inhibition was consistently observed across multiple studies. XN reduced NFκB nuclear accumulation [

94], decreased hepatic NFκB activity [

99], and blunted NFκB activation [

97], as well as inhibiting NFκB and its dependent genes [

99,

100]. This inhibition resulted in reduced expression of NFκB-dependent pro-inflammatory genes, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1α, MCP-1, and ICAM-1 [

94,

99,

100]. These coordinated anti-inflammatory effects across injury contexts are reflected in

Table 10.

Other Molecular Targets

Oxidative stress reduction: XN consistently increased the reduced glutathione content while suppressing lipid peroxidation markers, including malondialdehyde [

95,

96,

98], thiobarbituric acid reactive substances [

95], and 4-hydroxynonenal conjugates. This was accompanied by preservation or enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities, including superoxide dismutase [

95,

98], catalase [

95,

102], glutathione peroxidase [

95,

98], glutathione reductase [

95], and glutathione S-transferase [

95,

97,

102].

Cell-type-specific regulation of apoptosis: In hepatocytes, XN reduced apoptotic nuclei and suppressed pro-apoptotic pathways, including JNK phosphorylation and mitochondrial translocation, Bax translocation, cytochrome c and AIF release, and caspase-3 activation [

96,

98,

101]. Conversely, in activated hepatic stellate cells, XN promoted apoptosis [

99,

100], contributing to anti-fibrotic effects. This differential regulation—protecting hepatocytes while eliminating activated stellate cells—represents a therapeutically favorable mechanism.

Fibrosis inhibition: XN reduced expression of transforming growth factor-β1 [

98], a master regulator of fibrogenesis, along with downstream targets collagen type I and α-smooth muscle actin [

99]. Direct inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation , combined with induction of apoptosis in already-activated stellate cells [

99,

100], provides complementary anti-fibrotic mechanisms.

6.3. Integrated Hepato-Renal Protection

XN’s protective effects extend beyond the liver to the broader hepato-renal axis, reflecting the shared vulnerability of hepatic and renal tissues to oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic imbalance. In ethanol-induced oxidative injury models, XN provided dose-dependent protection not only in the liver but also in the kidney, lung, heart, and brain, reducing lipid peroxidation, preserving antioxidant enzyme activity, and normalizing injury biomarkers [

102]. These findings indicate that XN’s cytoprotective actions are systemic rather than organ-restricted.

Mechanistically, the same pathways mediating renal protection are involved in hepatoprotection. Antioxidant capacity and metabolic resilience are enhanced by AMPK and Nrf2 activation, while suppression of cytokine-driven tissue injury is mediated by inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation are central drivers of renal damage; thus, modulation of these pathways across organs supports XN’s classification as a broad-spectrum cytoprotective agent.

Table 9.

Hepatoprotection of xanthohumol.

Table 9.

Hepatoprotection of xanthohumol.

| Injury/Disease Model (System) | Dose/Regiment | Key Protective Outcomes | Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|

| HFD-induced NAFLD (rat) | Oral 20–30 mg/kg (per study) | ↓ body-weight gain; ↓ fat pads; ↓ fasting glucose/insulin; ↓ hepatic TGs/TC/FFAs; ↓ ALT/AST; ↓ lipid droplets | AMPK required: compound C abolished protection | [94] |

| CCl4 acute injury (rat) | Single CCl4 ± XN | ↓ liver weight; normalized LDH/GOT/GPT (p < 0.05); ↓ histopathology; ↑ GSH; ↓ TBARS/H2O2 | ↑ SOD, catalase, GPx, GR, GST | [95] |

| APAP (acetaminophen) toxicity (mouse and hepatocyte models) | XN pretreatment | ↓ mortality; ↓ ALT/AST; prevented GSH depletion; ↓ MDA; improved histology | Nrf2 via AMPK/Akt/GSK3β | [96] |

| CCl4 injury/inflammation–fibrosis (mouse) | XN co-treatment | Blunted pro-inflammatory & profibrogenic genes; ↓ NF-κB activity | ↓ serum transaminases; ↓ necrosis | [99] |

| APAP-induced injury with ferroptosis focus (HepaRG cells and mouse) | XN pretreatment | Ameliorated AILI in vitro & in vivo | Nrf2/xCT/GPX4 via Keap1 cysteine modification | [98] |

| Hepatitis C-associated liver injury (Tupaia belangeri) | Systemic XN | ↓ aminotransferases; ↓ histological activity index; ↓ steatosis; ↓ TGF-β1 | HCV core ↓ not significant (hepatoprotection > direct antiviral) | [48] |

| Warm ischemia–reperfusion (mouse) | XN pre-I/R | ↓ oxidative stress; ↓AKT & NF-κB activation; ↓ IL-1α/IL-6/MCP-1/ICAM-1 | No significant change in acute necrosis (H&E/TUNEL/ALT-AST) | [97] |

| NASH/hepatic fibrosis (mouse; hepatic stellate cell culture) | 0–20 µM (HSC), ≤50 µM (hepatocytes) | ↓ HSC activation; ↑ apoptosis in activated HSC; ↓ hepatic inflammation & profibrotic genes | Hepatocytes viable up to 50 µM | [100] |

| Aging-related alterations (aging rat) | 1 vs. 5 mg/kg/day | Dose-dependent modulation of apoptosis/oxidative stress/inflammation (p < 0.05) | AIF, BAD, BAX, Bcl-2, eNOS, HO-1, IL-1β, NF-κB2, PCNA, SIRT1, TNF-α | [101] |

| Ethanol-induced oxidative damage (rat; multi-organ assessment) | Dose per study | Dose-dependent protection (liver, kidney, lung, heart, brain) | Enzymes (SOD, catalase, GST); GOT/GPT/LDH; lipid peroxidation | [102] |

| Clinical safety/PK (human, Phase I XMaS trial) | Oral XN | Tolerated in healthy adults; safety/tolerability profiled | Formulation likely important | [5] |

| Metabolic comorbidity context (Review) | N.A. | Summarizes benefits in hyperlipidemia, obesity, T2DM | Mechanistic overlap with hepatic AMPK/Nrf2 | [104] |

Table 10.

Mechanistic actions of xanthohumol on hepatic and renal protective effects.

Table 10.

Mechanistic actions of xanthohumol on hepatic and renal protective effects.

| Pathway Readouts | Downstream Effects | Functional Outcome | Refs. |

|---|

| AMPK activation; compound C abrogates effects | ↓ SREBP-1c, ↓ ACC-1; improved metabolic parameters | Anti-steatosis; cytoprotection | [94,96] |

| Nrf2 activation; | ↑ GSH/SOD/CAT; xCT/GPX4engaged | Antioxidant defense; anti-ferroptosis | [94,96,98] |

Keap1→Nrf2; Covalent modification of Keap1

cysteines | Stabilizes Nrf2 → xCT/GPX4 | Blocks hepatic ferroptosis in APAP | [98] |

| NF-κB inhibition | ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1α; ↓ MCP-1, ICAM-1 | Anti-inflammatory; limits I/R cytokines | [94,97,99,100] |

| ↑AMPK→Akt→GSK3β→ | Nrf2 activation; cytoprotection | Integrated stress response | [96] |

| ↓AKT (I/R context) | ↓ inflammatory gene induction | Selective anti-inflammatory benefit | [97] |

| ↓ ROS/LPO ↑ GSH; ↓ MDA/TBARS/H2O2; ↓ 4-HNE | Preserved SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, GST; ↑ HMOX1 | Limits hepatocyte injury | [48,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] |

| Hepatocytes: ↓ JNK; ↓ Bax translocation; ↓ Cyt-c/AIF; ↓ Casp-3. | Cell-type specific apoptosis regulation: hepatocyte apoptosis ↓; HSC apoptosis ↑ | Anti-injury + anti-fibrotic | [48,96,100,101] |

Fibrosis signaling;

↓ TGF-β1; ↓ collagen I; ↓ α-SMA; ↓ HSC activation | ↓ Fibrogenesis, Matrix remodeling reduced | Anti-fibrotic | [48,99,100] |

| ↓ SREBP-1c/ACC-1; ↓ TGs/TC/FFAs | Lipogenesis inhibition;↓ hepatic lipid droplets | Anti-steatosis | [94] |

| Clinical translation/safety; Phase I safety; metabolic disease rationale | Supports human feasibility | Guides formulation & dosing work | [5,104] |

7. Metabolic Modulation

XN is a multifunctionally metabolic modulator, coordinating gut–liver signaling, cellular energy sensing, and lipid–glucose homeostasis rather than acting on a single pathway. In obesity and NAFLD models, XN improves whole-body insulin sensitivity by activating AMPK and SIRT1, which enhances GLUT4 translocation, suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis by decreasing PEPCK and G6Pase, and shifts mitochondrial metabolism toward oxidation [

105,

106]. These upstream changes translate into lower fasting glucose, improved insulin action, and reduced hepatic triglyceride accumulation, accompanied by decreased de novo lipogenesis-related genes such as

Srebp-1c,

Fas, and

Acc) and increased β-oxidation-related genes

Cpt-1 and

Pparα [

105,

106].

XN also directly remodels adipose tissue. It inhibits adipogenesis-related genes such as

Pparγ and

C/ebpα and promotes browning/thermogenesis-related gene

Ucp1, linking AMPK/SIRT1 activation to smaller, more oxidative fat depots [

98,

99]. In vivo, these effects are associated with higher energy expenditure, resistance to HFD-induced weight gain, and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC-1α/SIRT1) and BAT thermogenesis [

105,

106]. Suppression of NF-κB and cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and activation of Nrf2 antioxidant signaling further relieve insulin resistance and restore hepatic redox balance [

105,

106].

A defining feature of XN’s metabolic efficacy is its reliance on an intact gut microbiome. XN improved insulin resistance in conventionally colonized mice but not in germ-free animals, implicating microbial transformation and microbiota remodeling as essential mediators [

107]. This gut–liver axis underlies simultaneous reductions in inflammation, lipogenesis, and dysglycemia as hepatic NF-κB signaling quiets and AMPK/Nrf2 pathways dominate [

105,

107].

Translationally, XN shows promise but is limited by low oral bioavailability due to hydrophobicity and first-pass metabolism. Early human studies confirm safety and indicate improvements in CRP, glycemia, and microbiome composition [

5,

105]. Advances in formulation (nanocarriers, lipid systems, inclusion complexes) will be crucial for stabilizing parent XN and enabling rigorous clinical testing in NAFLD/NASH, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome [

105,

108].

In summary, XN drives a microbiota-dependent, AMPK/SIRT1-centered realignment of lipid and glucose metabolism while suppressing inflammatory stress, an integrated mechanism that supports advancing optimized formulations into larger outcome-focused human trials [

105,

106,

107]. A structured overview of XN’s metabolic targets, underlying mechanisms, representative outcomes, and dose ranges across preclinical and human studies is provided in

Table 11.

8. Dermatological and Joint-Protective Effects

Accumulating evidence supports XN as a cytoprotective compound capable of attenuating oxidative stress, suppressing inflammatory signaling, preserving extracellular matrix (ECM) integrity, and limiting tissue degeneration in both cutaneous and joint-related contexts. These properties are particularly relevant in pathological conditions driven by chronic inflammation, oxidative injury, and dysregulated matrix remodeling.

8.1. Protection of Dermatological and Joint Conditions