Energy Availability, Body Composition, and Phase Angle Among Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts During a Competitive Season

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Ethics

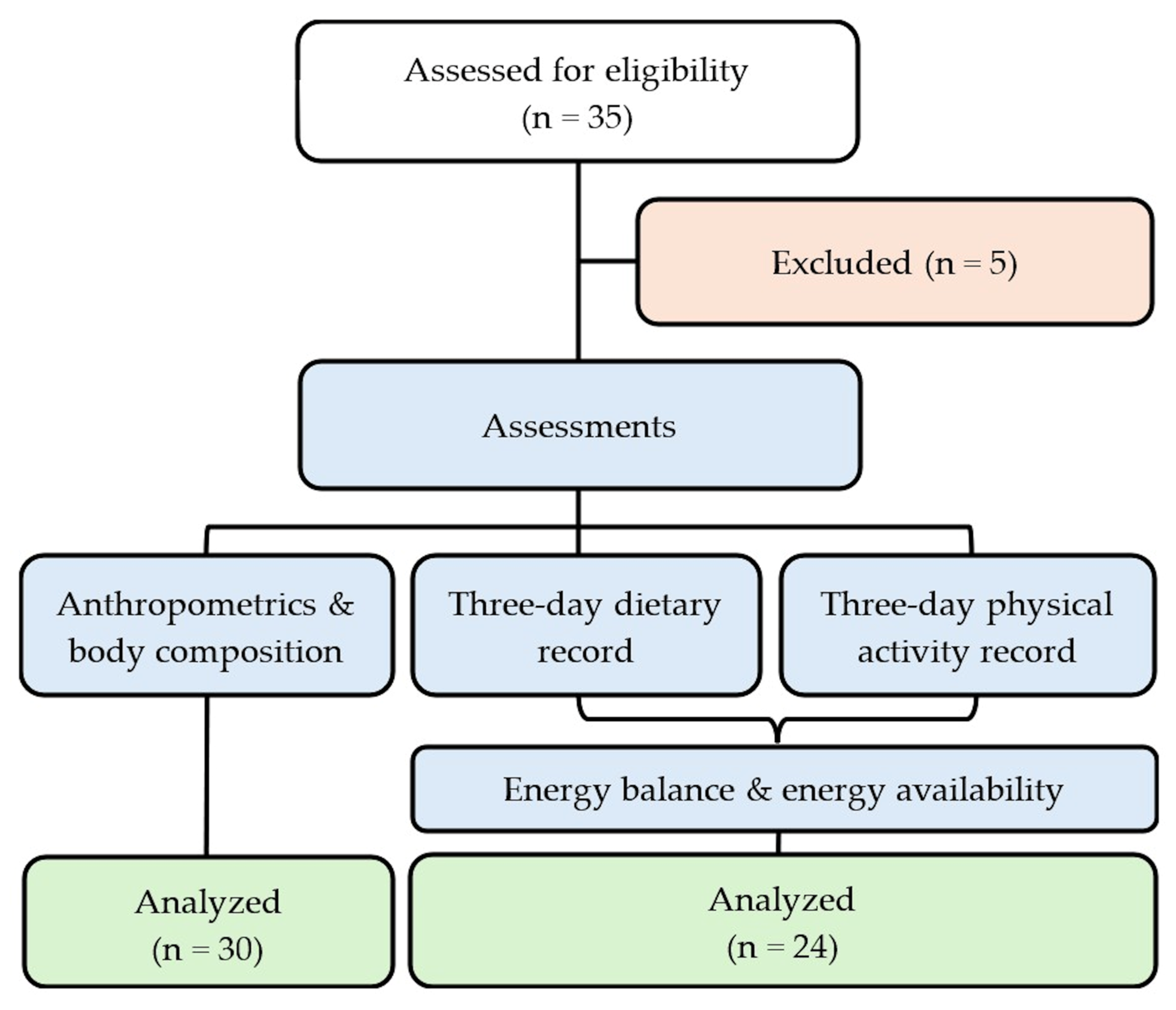

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Demographic Characteristics

2.4. Anthropometrics and Body Composition

2.5. Analysis of Energy Intake

2.6. Analysis of Energy Expenditure

2.7. Energy Balance and Energy Availability

2.8. Assessment of Dietary Underreporting

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

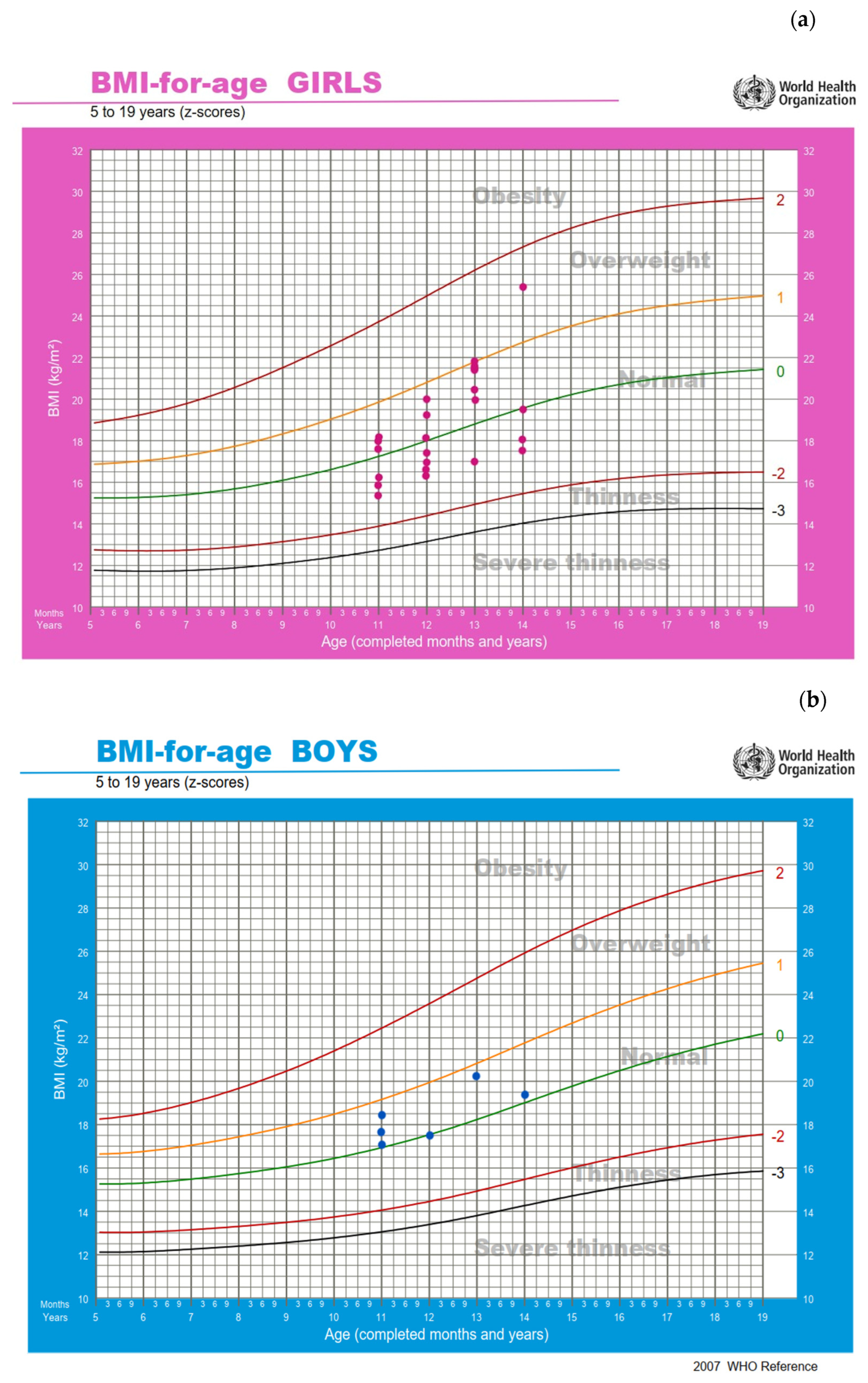

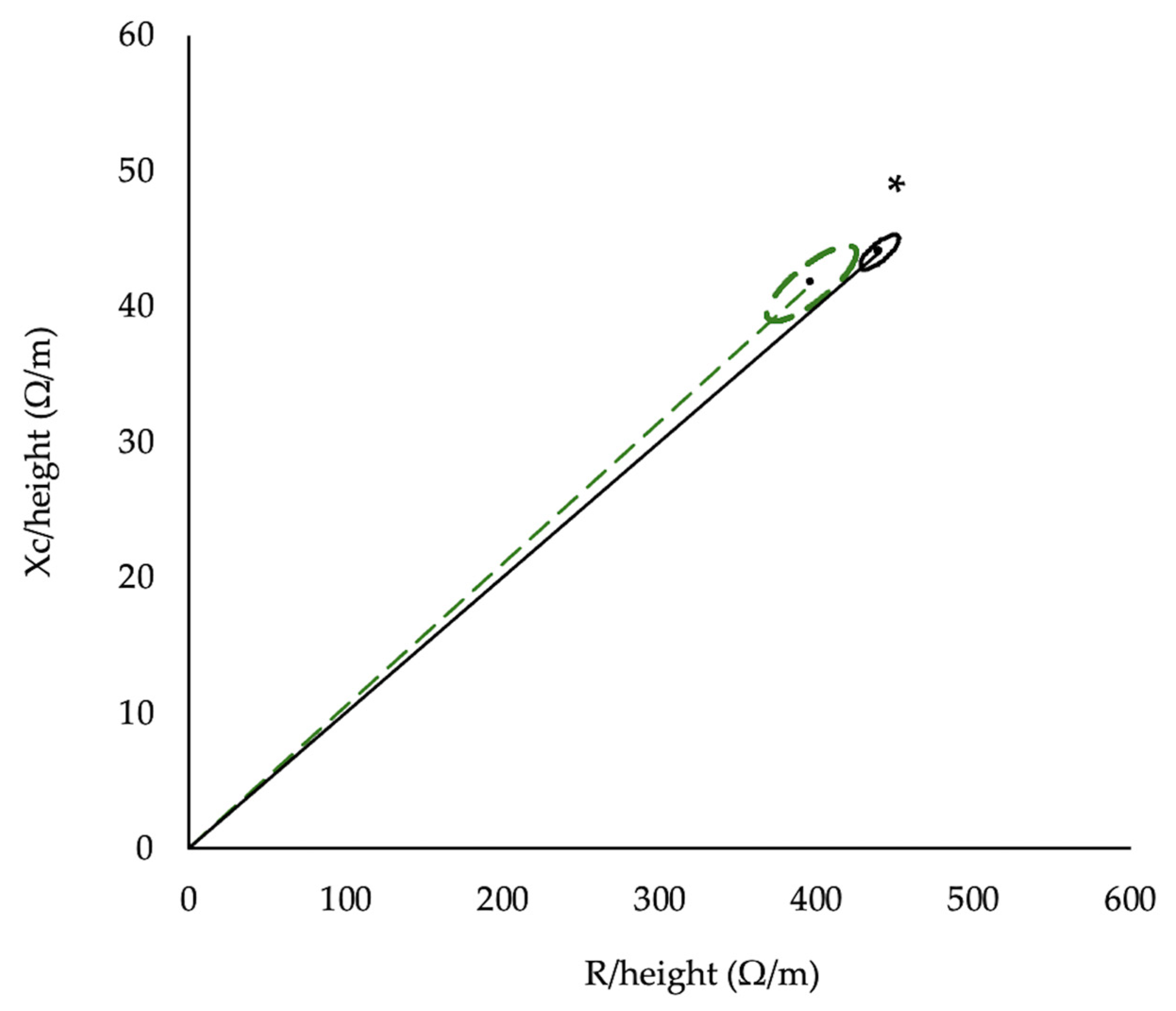

3.2. Anthropometrics and Body Composition

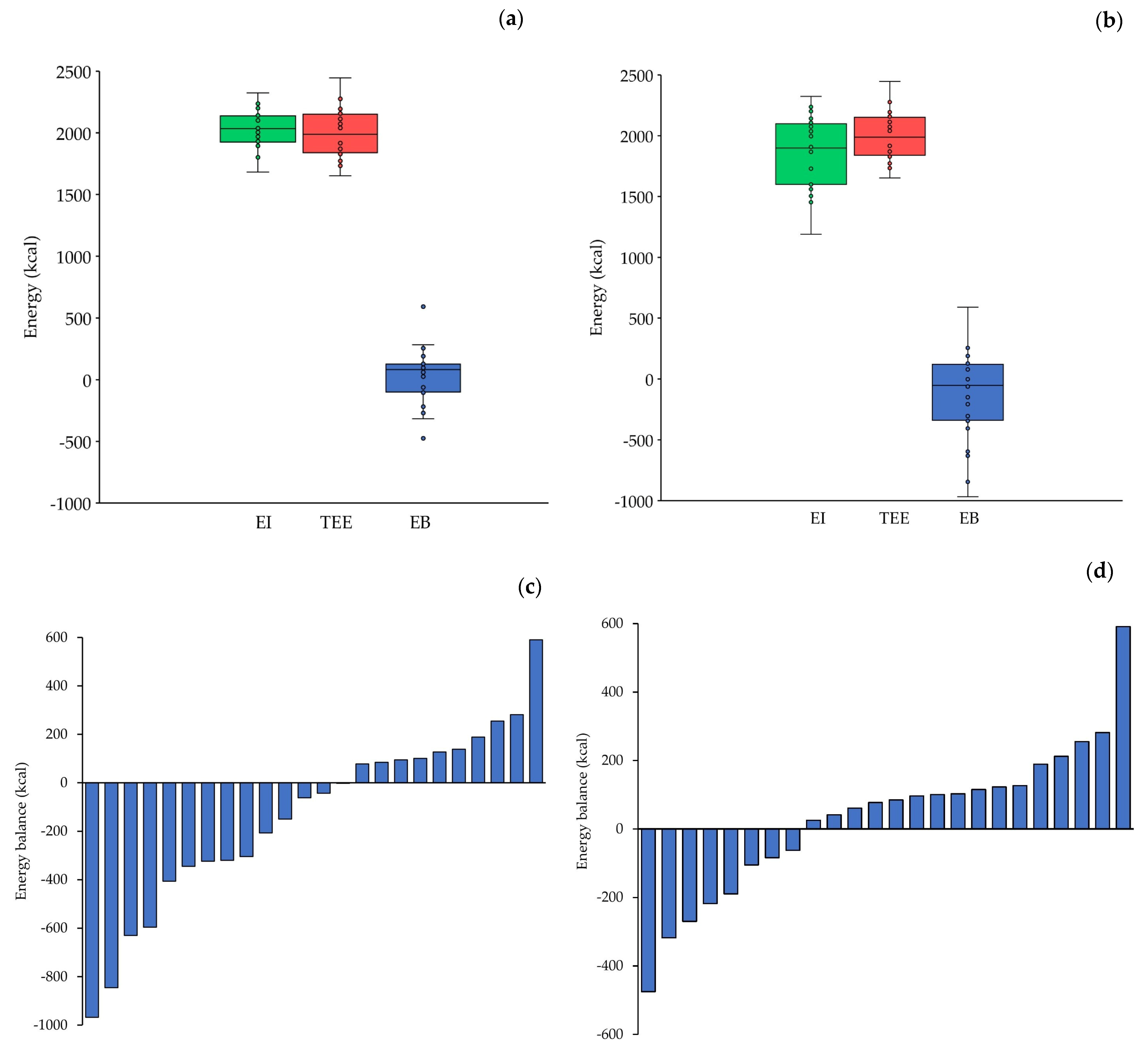

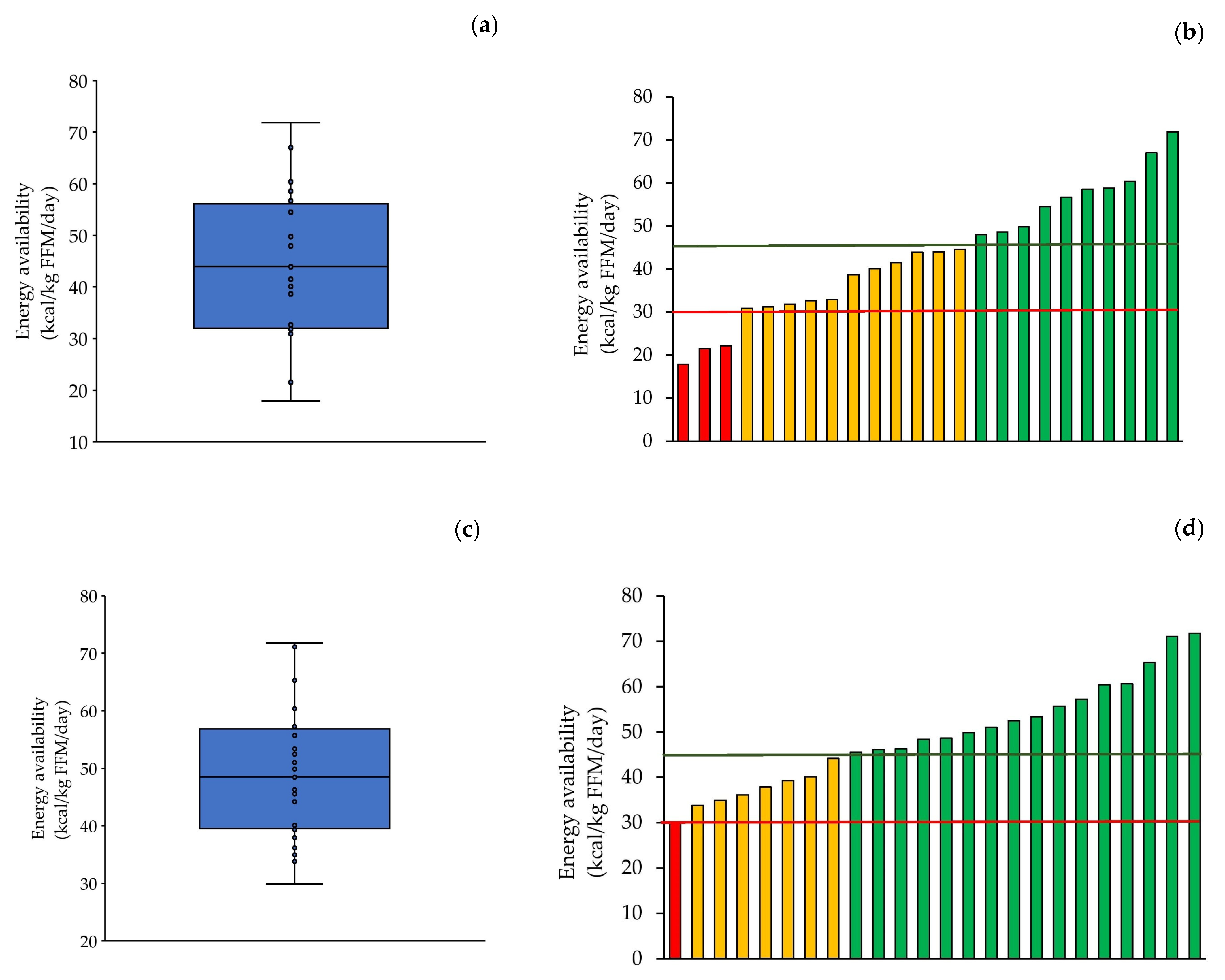

3.3. Energy Balance and Energy Availability

3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCM | Body cell mass |

| BIA | Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

| BIVA | Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| EA | Energy availability |

| EB | Energy balance |

| ECW | Extracellular water |

| EEE | Exercise energy expenditure |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| EI | Energy intake |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| FM | Fat mass |

| LEA | Low energy availability |

| MET | Metabolic equivalent of task |

| PAL | Physical activity level |

| R | Resistance |

| REDs | Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport |

| REE | Resting energy expenditure |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TBW | Total body water |

| TEE | Total energy expenditure |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| Xc | Reactance |

| Ζ | Impedance |

| φ | Phase angle |

References

- Mountjoy, M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Bailey, D.M.; Burke, L.M.; Constantini, N.; Hackney, A.C.; Heikura, I.A.; Melin, A.; Pensgaard, A.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; et al. 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) Consensus Statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1073–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areta, J.L.; Taylor, H.L.; Koehler, K. Low Energy Availability: History, Definition and Evidence of Its Endocrine, Metabolic and Physiological Effects in Prospective Studies in Females and Males. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipla, K.; Kraemer, R.R.; Constantini, N.W.; Hackney, A.C. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S): Elucidation of Endocrine Changes Affecting the Health of Males and Females. Hormones 2021, 20, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.A.; Nguyen, D.D.; Ruby, B.C.; Schoeller, D.A. Maximal Sustained Levels of Energy Expenditure in Humans during Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 2359–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, C.; Dugas, L.R.; Ocobock, C.; Carlson, B.; Speakman, J.R.; Pontzer, H. Extreme Events Reveal an Alimentary Limit on Sustained Maximal Human Energy Expenditure. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw0341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hooren, B.; Rietjens, G.; Plasqui, G. Longitudinal Assessment of Total Daily Energy Expenditure in Professional Cyclists Supports a Maximal Sustainable Metabolic Ceiling. Curr. Biol. 2026, 36, 151–160.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsohn, A.; Scharhag-Rosenberger, F.; Cassel, M.; Weber, J.; Guzman, A.d.G.; Mayer, F. Physical Activity Levels to Estimate the Energy Requirement of Adolescent Athletes. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2011, 23, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, U.G.; Bosaeus, I.; De Lorenzo, A.D.; Deurenberg, P.; Elia, M.; Gómez, J.M.; Heitmann, B.L.; Kent-Smith, L.; Melchior, J.C.; Pirlich, M.; et al. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis—Part I: Review of Principles and Methods. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, B.R.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Cereda, E.; Prado, C.M. Exploring the Potential Role of Phase Angle as a Marker of Oxidative Stress: A Narrative Review. Nutrition 2022, 93, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Dalla-Rovere, L.; García-Olivares, M.; Abuín-Fernández, J.; Sánchez-Torralvo, F.J.; Doulatram-Gamgaram, V.K.; Hernández-Sanchez, A.M.; García-Almeida, J.M. Phase Angle and Handgrip Strength as a Predictor of Disease-Related Malnutrition in Admitted Patients: 12-Month Mortality. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.A.; de Melo, G.F.; de Almeida Filho, E.J.B.; Silvino, V.O.; de Albuquerque Neto, S.L.; Ribeiro, S.L.G.; Silva, A.S.; dos Santos, M.A.P. Correlation between Phase Angle and Muscle Mass, Muscle Function, and Health Perception in Community-Dwelling Older Women. Sport Sci. Health 2023, 19, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadinian, F.; Eshaghian, N.; Tarrahi, M.J.; Amani, R.; Akbari, M.; Shirani, F. Phase Angle as an Indicator of Nutritional Status: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Iranian Population. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, E.; Pompeo, A.; Cirillo, F.T.; Vilaça-Alves, J.; Costa, P.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Dourado, A.C.; Afonso, J.; Casanova, F. Relationship between Bioelectrical Impedance Phase Angle and Upper and Lower Limb Muscle Strength in Athletes from Several Sports: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports 2023, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Oliva, A.; Ávila-Nava, A.; Rodríguez-Aguilar, E.A.; Trujillo-Mercado, A.; García-Guzmán, A.D.; Pinzón-Navarro, B.A.; Fuentes-Servín, J.; Guevara-Cruz, M.; Medina-Vera, I. Association between Phase Angle and the Nutritional Status in Pediatric Populations: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1142545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popiolek-Kalisz, J.; Kalisz, G. Malnutrition Assessed with Phase Angle and Mortality Risk in Heart Failure—A Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, R.D.; Ward, L.C.; Larsen, S.C.; Heitmann, B.L. Can Change in Phase Angle Predict the Risk of Morbidity and Mortality during an 18-Year Follow-up Period? A Cohort Study among Adults. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1157531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Han, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, L.; Tang, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y. Lower Phase Angle as a Marker for Poor Prognosis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Cohort Study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1580037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeskops, S.; Oliver, J.L.; Read, P.J.; Cronin, J.B.; Myer, G.D.; Lloyd, R.S. The Physiological Demands of Youth Artistic Gymnastics: Applications to Strength and Conditioning. Strength Cond. J. 2019, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Garthe, I.; Meyer, N. Energy Needs and Weight Management for Gymnasts. In Gymnastics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos, N.A.; Markou, K.B.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Benardot, D.; Leglise, M.; Vagenakis, A.G. Growth Retardation in Artistic Compared with Rhythmic Elite Female Gymnasts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 3169–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, K.B.; Mylonas, P.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Kontogiannis, A.; Leglise, M.; Vagenakis, A.G.; Georgopoulos, N.A. The Influence of Intensive Physical Exercise on Bone Acquisition in Adolescent Elite Female and Male Artistic Gymnasts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 4383–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, A.; Markou, K.B.; Vagenakis, G.A.; Benardot, D.; Leglise, M.; Kourounis, G.; Vagenakis, A.G.; Georgopoulos, N.A. Delayed but Normally Progressed Puberty Is More Pronounced in Artistic Compared with Rhythmic Elite Gymnasts Due to the Intensity of Training. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 6022–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakše, B.; Jakše, B.; Čuk, I.; Šajber, D. Body Composition, Training Volume/Pattern and Injury Status of Slovenian Adolescent Female High-performance Gymnasts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, K.N.d.O.; Vieira, M.M.; Aleixo, I.M.S.; Wilke, C.F.; Wanner, S.P. Estimated Energy Expenditure and Training Intensity in Young Female Artistic Gymnasts. Mot. Rev. Educ. Fís. 2022, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal Veitia, W.; Campos, Y.D. Body Composition Analysis Using Bioelectrical Parameters in the Cuban Sporting Population. Arch. Med. Deporte 2017, 34, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilo, A.; Lozano, L.; Tauler, P.; Nafría, M.; Colom, M.; Martínez, S. Nutritional Status and Implementation of a Nutritional Education Program in Young Female Artistic Gymnasts. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.G.; Silva, H.H.; Paiva, T. Sleep Duration, Body Composition, Dietary Profile and Eating Behaviours among Children and Adolescents: A Comparison between Portuguese Acrobatic Gymnasts. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.G.; Paiva, T. Low Energy Availability and Low Body Fat of Female Gymnasts before an International Competition. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 15, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Villa-Vicente, J.G.; Seco-Calvo, J.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Collado, P.S. Body Composition, Dietary Intake and the Risk of Low Energy Availability in Elite-Level Competitive Rhythmic Gymnasts. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besor, O.; Redlich, N.; Constantini, N.; Weiler-Sagie, M.; Monsonego Ornan, E.; Lieberman, S.; Bentur, L.; Bar-Yoseph, R. Assessment of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) Risk among Adolescent Acrobatic Gymnasts. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purenović-Ivanović, T.; Popović, R.; Bubanj, S.; Stanković, R. Body Composition in High-Level Female Rhythmic Gymnasts of Different Age Categories. Sci. Sports 2019, 34, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG). 2025–2028 Code of Points. Available online: https://www.gymnastics.sport/site/ (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Schofield, W.N. Predicting Basal Metabolic Rate, New Standards and Review of Previous Work. Hum. Nutr. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 39, 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Butte, N.F.; Watson, K.B.; Ridley, K.; Zakeri, I.F.; McMurray, R.G.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Crouter, S.E.; Herrmann, S.D.; Bassett, D.R.; Long, A.; et al. A Youth Compendium of Physical Activities: Activity Codes and Metabolic Intensities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, S.D.; Willis, E.A.; Ainsworth, B.E. The 2024 Compendium of Physical Activities and Its Expansion. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Dietary Reference Values for Nutrients Summary Report. EFSA Support. Public. 2017, 14, e15121E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palo, T.; Messina, G.; Edefonti, A.; Perfumo, F.; Pisanello, L.; Peruzzi, L.; Di Iorio, B.; Mignozzi, M.; Vienna, A.; Conti, G.; et al. Normal Values of the Bioelectrical Impedance Vector in Childhood and Puberty. Nutrition 2000, 16, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccoli, A.; Pillon, L.; Dumler, F. Impedance Vector Distribution by Sex, Race, Body Mass Index, and Age in the United States: Standard Reference Intervals as Bivariate Z Scores. Nutrition 2002, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Growth Reference Data for 5–19 Years. Available online: http://www.who.int/growthref/en/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- D’Alessandro, C.; Morelli, E.; Evangelisti, I.; Galetta, F.; Franzoni, F.; Lazzeri, D.; Piazza, M.; Cupisti, A. Profiling the Diet and Body Composition of Subelite Adolescent Rhythmic Gymnasts. Hum. Kinet. 2007, 19, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürimäe, J.; Remmel, L.; Tamm, A.L.; Purge, P.; Maasalu, K.; Tillmann, V. Associations of Circulating Irisin and Fibroblast Growth Factor-21 Levels with Measures of Energy Homeostasis in Highly Trained Adolescent Rhythmic Gymnasts. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolimechkov, S.; Yanev, I.; Kiuchukov, I.; Petrov, L.; Alexandrova, A.; Zaykova, D.; Stoimenov, E. Nutritional Status and Body Composition of Young Artistic Gymnasts from Bulgaria. J. Appl. Sports Sci. 2019, 3, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, M.; Antosik, K.; Decyk, A.; Kurowska, K.; Skiba, D. Body Composition and Anthropometric Indicators in Children and Adolescents 6–15 Years Old. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, S.K.; Feidantsis, K.G.; Hassapidou, M.N.; Methenitis, S. The Specific Impact of Nutrition and Physical Activity on Adolescents’ Body Composition and Energy Balance. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2021, 92, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, R.C.; Benardot, D.; Martin, D.E.; Cody, M.M. Relationship between Energy Deficits and Body Composition in Elite Female Gymnasts and Runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleleo, D.; Bartolomeo, N.; Cassano, L.; Nitti, A.; Susca, G.; Mastrototaro, G.; Armenise, U.; Zito, A.; Devito, F.; Scicchitano, P.; et al. Evaluation of Body Composition with Bioimpedence. A Comparison between Athletic and Non-Athletic Children. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Marginet, M.; Castizo-Olier, J.; Rodríguez-Zamora, L.; Iglesias, X.; Rodríguez, F.A.; Chaverri, D.; Brotons, D.; Irurtia, A. Bioelectrical Impedance Vector Analysis (BIVA) for Measuring the Hydration Status in Young Elite Synchronized Swimmers. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koury, J.C.; Trugo, N.M.F.; Torres, A.G. Phase Angle and Bioelectrical Impedance Vectors in Adolescent and Adult Male Athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Cruz Marcos, S.; Redondo Del Río, M.P.; de Mateo Silleras, B. Applications of Bioelectrical Impedance Vector Analysis (Biva) in the Study of Body Composition in Athletes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Durda-Masny, M.; Hanć, T. Reference Data for Body Composition Parameters in Normal-Weight Polish Adolescents: Results from the Population-Based ADOPOLNOR Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 5021–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lioret, S.; Touvier, M.; Balin, M.; Huybrechts, I.; Dubuisson, C.; Dufour, A.; Bertin, M.; Maire, B.; Lafay, L. Characteristics of Energy Under-Reporting in Children and Adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, T.L.; Ho, Y.Y.; Rollo, M.E.; Collins, C.E. Validity of Dietary Assessment Methods When Compared to the Method of Doubly Labeled Water: A Systematic Review in Adults. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridou, A.; Rodopaios, N.E.; Mougios, V.; Koulouri, A.A.; Vasara, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Skepastianos, P.; Hassapidou, M.; Kafatos, A. Effects of Periodic Religious Fasting for Decades on Nutrient Intakes and the Blood Biochemical Profile. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, J.S.; Hellsten, Y.; Melin, A.K.; Hansen, M. Short-Term Severe Low Energy Availability in Athletes: Molecular Mechanisms, Endocrine Responses, and Performance Outcomes—A Narrative Review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, K.; Achtzehn, S.; Braun, H.; Mester, J.; Schaenzer, W. Comparison of Self-Reported Energy Availability and Metabolic Hormones to Assess Adequacy of Dietary Energy Intake in Young Elite Athletes. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, N.; Uchiyama, E.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Yamada, Y.; Okuyama, K. Association of Energy Availability with Resting Metabolic Rates in Competitive Female Teenage Runners: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.O.C.; Ferrari, G.; Langer, R.D.; Cossio-Bolaños, M.; Gomez-Campos, R.; Lázari, E.; Moraes, A.M. Phase Angle and Its Determinants among Adolescents: Influence of Body Composition and Physical Fitness Level. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.C.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Bielemann, R.M.; Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B. Phase Angle and Its Determinants in Healthy Subjects: Influence of Body Composition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Areta, J.L.; Van Genechten, L.; Langan-Evans, C.; Pedlar, C.R.; Rodas, G.; Sale, C.; Walsh, N.P. Does Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) Syndrome Exist? Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2793–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n = 30 | n = 24 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 12.4 ± 1.1 |

| Training age (years) | 7.6 ± 1.7 | 7.7 ± 1.7 |

| Training duration (h/week) | 17.1 ± 3.9 | 17.4 ± 3.9 |

| Variable | n = 30 | n = 24 |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 42.5 ± 8.9 | 42.6 ± 9.3 |

| Height (m) | 1.50 ± 0.09 | 1.50 ± 0.09 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.7 ± 2.2 | 18.8 ± 2.4 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 6.9 ± 2.6 |

| Fat mass (%) | 16.1 ± 3.4 | 16.0 ± 3.7 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 35.5 ± 7.1 | 35.7 ± 7.4 |

| Fat-free mass (%) | 83.9 ± 3.4 | 84.0 ± 3.7 |

| Total body water (L) | 27.0 ± 5.2 | 27.1 ± 5.5 |

| Total body water (%) | 63.7 ± 2.7 | 63.8 ± 2.9 |

| Extracellular water (L) | 12.7 ± 1.8 | 12.7 ± 1.9 |

| Extracellular water (%) | 30.3 ± 2.4 | 30.3 ± 2.5 |

| Intracellular water (L) | 13.9 ± 2.8 | 13.9 ± 2.9 |

| Intracellular water (%) | 33.1 ± 3.6 | 32.8 ± 3.3 |

| Third-space water (L) | 0.3 ± 1.7 | 0.5 ± 1.6 |

| Body cell mass (kg) | 19.9 ± 3.9 | 19.9 ± 4.1 |

| Resistance (Ω) | 589 ± 59 | 586 ± 63 |

| Reactance (Ω) | 62.0 ± 5.6 | 61.9 ± 6.2 |

| Phase angle (°) | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.6 |

| Impedance at 5 kHz (Ω) | 669 ± 62 | 666 ± 66 |

| Impedance at 50 kHz (Ω) | 593 ± 59 | 589 ± 63 |

| Impedance at 100 kHz (Ω) | 562 ± 57 | 559 ± 61 |

| Impedance at 200 kHz (Ω) | 535 ± 56 | 531 ± 59 |

| r or ρ | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Fat mass (kg) | −0.365 a | 0.080 |

| Fat mass (%) | 0.002 | 0.993 |

| Body cell mass (kg) | −0.576 | 0.003 |

| Resistance (Ω) | 0.643 | <0.001 |

| Reactance (Ω) | 0.476 | 0.019 |

| Phase angle (°) | −0.231 | 0.276 |

| Total energy expenditure (kcal) | −0.490 | 0.015 |

| Energy balance (kcal) | 0.912 | <0.001 |

| r or ρ | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Fat mass (kg) | −0.418 a | 0.042 |

| Fat mass (%) | −0.023 | 0.913 |

| Body cell mass (kg) | −0.659 | <0.001 |

| Resistance (Ω) | 0.770 | <0.001 |

| Reactance (Ω) | 0.497 | 0.014 |

| Phase angle (°) | −0.345 | 0.099 |

| Total energy expenditure (kcal) | −0.571 | 0.004 |

| Energy balance (kcal) | 0.836 | <0.001 |

| r or ρ | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 0.463 | 0.010 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.588 a | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 0.428 a | 0.018 |

| Fat mass (%) | 0.351 | 0.057 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 0.400 | 0.029 |

| Fat-free mass (%) | −0.351 | 0.057 |

| Total body water (L) | 0.395 | 0.031 |

| Total body water (%) | −0.409 | 0.025 |

| Extracellular water (L) | 0.364 | 0.048 |

| Extracellular water (%) | −0.497 | 0.005 |

| Intracellular water (L) | 0.341 | 0.065 |

| Intracellular water (%) | −0.230 a | 0.221 |

| Body cell mass (kg) | 0.340 | 0.066 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Grompanopoulou, A.; Kypraiou, A.; Milosis, D.C.; Chourdakis, M.; Petridou, A. Energy Availability, Body Composition, and Phase Angle Among Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts During a Competitive Season. Nutrients 2026, 18, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030519

Grompanopoulou A, Kypraiou A, Milosis DC, Chourdakis M, Petridou A. Energy Availability, Body Composition, and Phase Angle Among Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts During a Competitive Season. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030519

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrompanopoulou, Anneta, Antigoni Kypraiou, Dimitrios C. Milosis, Michael Chourdakis, and Anatoli Petridou. 2026. "Energy Availability, Body Composition, and Phase Angle Among Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts During a Competitive Season" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030519

APA StyleGrompanopoulou, A., Kypraiou, A., Milosis, D. C., Chourdakis, M., & Petridou, A. (2026). Energy Availability, Body Composition, and Phase Angle Among Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts During a Competitive Season. Nutrients, 18(3), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030519