Systemic Factors Fuel Food Insecurity Among Collegiate Student-Athletes: Qualitative Findings from the Running on Empty Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Unique Considerations for FI Risk Among Student-Athletes

1.2. Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

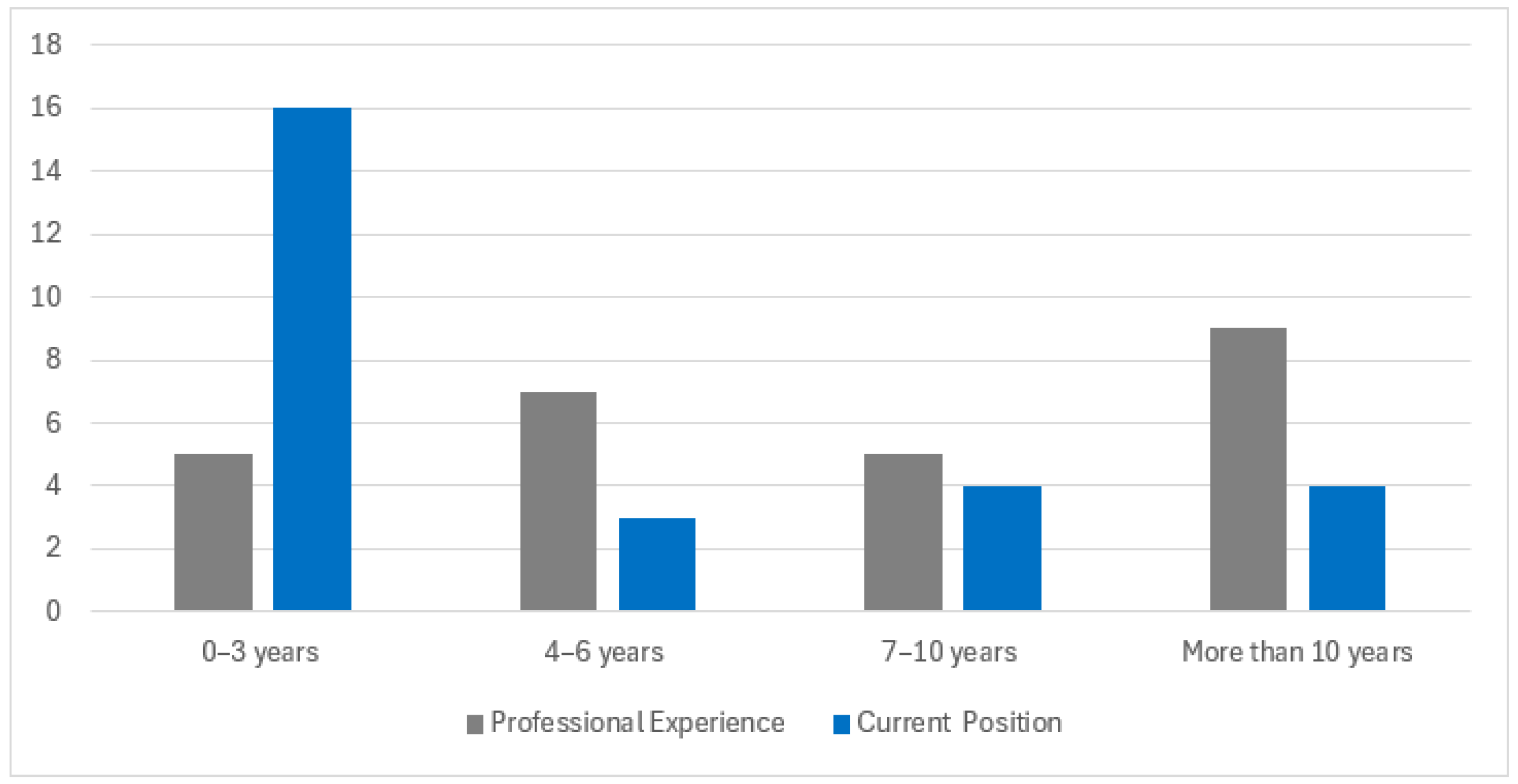

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and Procedures

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Understanding of FI Among Professionals Working with Student-Athletes

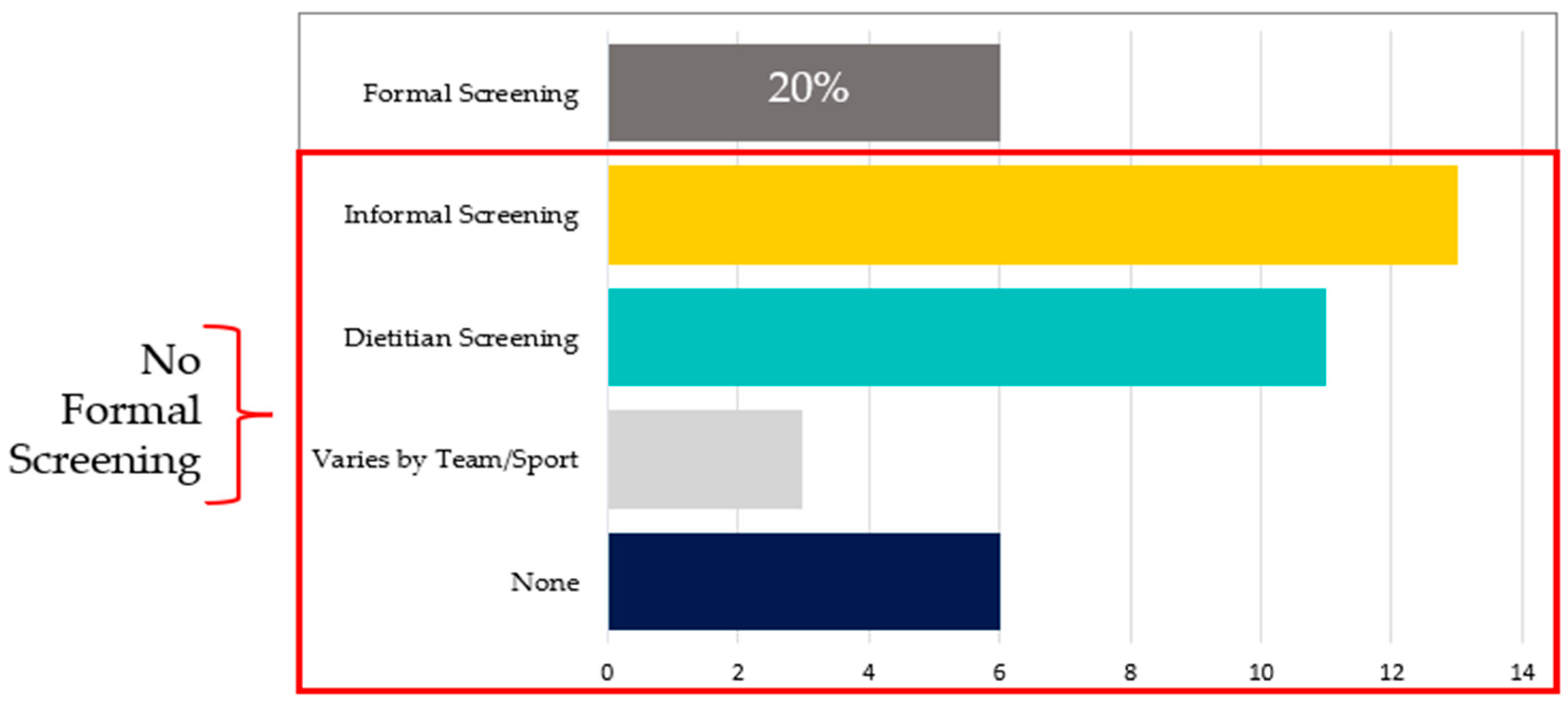

3.2. FI Screening Protocols Employed with Student-Athletes

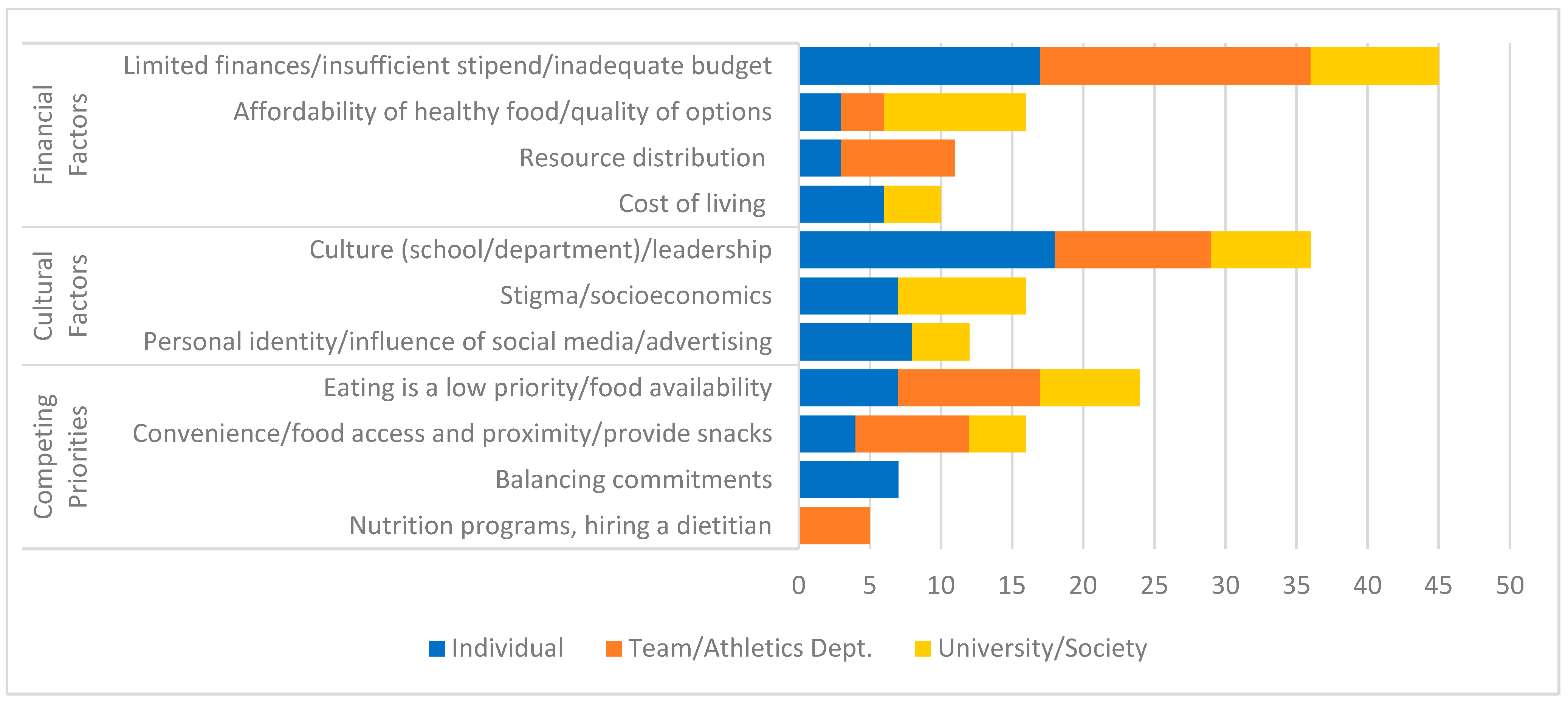

3.3. Factors Influencing the Prevalence of FI Among This Population

3.3.1. Theme 1: Individual Contributing Factors

3.3.2. Theme 2: Team/Athletic Department Contributing Factors

3.3.3. Theme 3: University/Societal Contributing Factors

3.4. Calculation of Student-Athlete Stipends

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Determinants of FI Among Collegiate Student-Athletes

4.2. Systems-Level Determinants of FI Among Collegiate Student-Athletes

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FI | Food insecurity |

| GPA | Grade Point Average |

| NCAA | National Collegiate Athletic Association |

| NIL | Name, image, likeness |

References

- US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Douglas, C.C.; Camel, S.P.; Mayeux, W. Food insecurity among female collegiate athletes exists despite university assistance. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 4, 1904–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumina Foundation. Available online: www.luminafoundation.org/resource/hungry-to-win/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Poll, K.L.; Holben, D.H.; Valliant, M.; Joung, D. Food insecurity is associated with disordered eating behaviors in NCAA Division 1 male collegiate athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 60, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reader, J.; Gordon, B.; Christensen, N. Food Insecurity among a cohort of Division I student-athletes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Alexandria, VA, USA, 2000.

- National Collegiate Athletic Association-1. Available online: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2015/2/13/transfer-terms.aspx (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Pacenta, J.; Starkoff, B.E.; Lenz, E.K.; Shearer, A. Prevalence of and contributors to food insecurity among college athletes: A scoping review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimera, L.; Dellana, J.; Farris, A.; Wentz, L.; Harman, T.; Dommel, A.; Rushing, K.; Stowers, L.; Behrens, C., Jr. Food insecurity among college student athletes in the southeastern region: A multi-site study. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. Conf. Proc. 2023, 16, 272. [Google Scholar]

- Stowers, L.; Harman, T.; Pavela, G.; Fernandez, J.R. The impact of food security status on body composition changes in collegiate football players. Int. J. Sports Exerc. Med. 2022, 8, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Institute. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/assessing-food-insecurity-campus (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- El Zein-1, A.; Shelnutt, K.P.; Colby, S.; Vilaro, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Greene, G.; Olfert, M.D.; Riggsbee, K.; Morrell, J.S.; Mathews, A.E. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among U.S. college students: A multi-institutional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, R.L.; McArthur, L.H.; Hood, L.B.; Berner, M.; Steeves, E.T.A.; Connell, C.L.; Wall-Bassett, E.; Spence, M.; Babatunde, O.T.; Kelly, E.B.; et al. Expenditure, coping, and academic behaviors among food-insecure college students at 10 higher education institutes in the Appalachian and southeastern regions. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, E.A.; Martinez, S.; Leung, C.W. “It’s a feeling that one is not worth food”: A qualitative study exploring the psychosocial experience and academic consequences of food insecurity among college students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woerden, I.; Hruschka, D.; Vega-Lopez, S.; Bruening, M. Food insecure college students and objective measurements of their unused meal plans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Adetunji, H.; Oskrochi, R. Food and mental health: Relationship between food and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among university students in the United Kingdom. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaalouk, D.; Boumosleh, J.M.; Helou, L.; Abou Jaoude, M. Dietary patterns, their covariates, and associations with severity of depressive symptoms among university students in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurster, B.; Garrity, K.; Al-Muhanna, K.; Guerra, K.K. The pathophysiology of food insecurity: A narrative review and system map. J. Nutr. Ed. Behav. 2022, 54, S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton-López, M.M.; López-Cevallos, D.F.; Cancel-Tirado, D.I.; Vazquez, L. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among students attending a midsize rural university in Oregon. J. Nutr. Edu Behav. 2014, 46, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserfurth, P.; Palmowski, J.; Hahn, A.; Krüger, K. Reasons for and consequences of low energy availability in female and male athletes: Social environment, adaptations, and prevention. Sports Med. Open 2020, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the female athlete triad—Relative energy deficiency in sport (red-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mountjoy-2, M.L.; Burke, L.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Relative energy deficiency in sport: The tip of an iceberg. Int. J. Sport. Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Abbey, E.; McKenzie, M.; Karpinski, C. Prevalence of food insecurity in NCAA Division III collegiate athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collegiate Athletic Association-2. Available online: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/5/11/our-division-i-students.aspx (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Christensen, N.; van Woerden, I.; Aubuchon-Endsley, N.L.; Fleckenstein, P.; Olsen, J.; Blanton, C. Diet quality and mental health Status among Division 1 female collegiate athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Work hours. Unpublished data. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn-Hatfield, R.L.; Hood, L.B.; Hege, A. A decade of college student hunger: What we know and where we need to go. Front. Pub Health 2022, 10, 837724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuy Castellanos, D.; Holcomb, J. Food insecurity, financial priority, and nutrition literacy of university students at a mid-size private university. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacre, K.; Chang, Y.; Holben, D.H.; Roseman, M.G. Cooking facilities and food procurement skills reduce food insecurity among college students: A pilot study. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol, L.L.; Robb, C.A.; McKinley, E.M.; Wood, M. Very low food security status is related to lower cooking self-efficacy and less frequent food preparation behaviors among college students. J. Nutr. Ed. Behav. 2019, 51, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M.; Arrowood, J.; Farris, A.; Griffin, J. Assessing food security through cooking and food literacy among students enrolled in a basic food science lab at Appalachian State University. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, S.L.; Rodriguez-Jordan, J.; McCoin, M. Integrated nutrition and culinary education in response to food insecurity in a public university. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.E.; Davis, K.E.; Wang, W. Low food security present on college campuses despite high nutrition literacy. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.N.; Lenk, K.; Lust, K.; McGuire, C.M.; Porta, C.M.; Stebleton, M. Sociodemographic and health disparities among students screening positive for food insecurity: Findings from a large college health surveillance system. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 29, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, N.; Tapanee, P.; Persell, A.; Tolar-Peterson, T. Food insecurity, depression, and race: Correlations observed among college students at a university in the southeastern United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anziano, J. Food Insecurity Among College Athletes at a Public University in New England. Master Thesis, Southern Connecticut State University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davitt, E.D.; Heer, M.M.; Winham, D.M.; Knoblauch, S.T.; Shelley, M.C. Effects of COVID-19 on university student food security. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collegiate Athletic Association-3. Available online: https://www.ncaa.org/news/2020/3/30/division-i-council-extends-eligibility-for-student-athletes-impacted-by-covid-19.aspx (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using Zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Available online: www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/what-is-rural (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- American Council on Education. Available online: https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/carnegie-classification/classification-methodology/2021-size-setting-classification/ (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2022. Northern Arizona University. Available online: https://www.azauditor.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/NorthernArizonaUniversityJune30_2022FinancialReport.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- 2022–2023 University Budget. Cal Poly. Available online: https://afd.calpoly.edu/budget/docs/fy2022-23-budget-book.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Annual Budget & Expenditure Reports, Sacramento State. Available online: https://www.csus.edu/administration-business-affairs/budget-planning/planning-oversight.html (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Statement of Revenues and Expenses. U C Davis Sports. Available online: https://ucdavisaggies.com/sports/2021/11/11/statement-of-revenues-and-expenses.aspx (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- University of Northern Colorado, NCAA Agreed-Upon Procedures, Fiscal Year Ended 30 June 2021. Available online: https://leg.colorado.gov/audits/university-northern-colorado-ncaa-agreed-upon-procedures-fiscal-year-ended-june-30-202 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- FY22 GL EADA NCAA Financial Report (Corrected). Idaho State University. Available online: https://isubengals.com/documents/2022/10/26/FY22_GL_EADA_NCAA_Financial_Report__Corrected_.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- NCAA Membership Financial Reporting System. University of Idaho. Available online: https://www.uidaho.edu/-/media/UIdaho-Responsive/Files/general-counsel/contracts/ncaa/fy22-ncaa-report.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- NCAA Reports 2022. Montana State University. Available online: https://msubobcats.com/sports/2024/11/21/ncaa-reports.aspx (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- 2022 EADA Survey. University of Montanna. Available online: https://www.umt.edu/institutional-research/student-consumer-information/eada2022completed.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Report on the Status and Future of Intercollegiate Athletics at Portland State University. Available online: https://www.pdx.edu/faculty-senate/sites/g/files/znldhr3021/files/2022-05/IAB%20Annual%20Report%202021-22.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Weber State University Intercollegiate Athletics Program Statement of Revenues and Expenses for the Year Ended 30 June 2022. Available online: https://reporting.auditor.utah.gov/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=0151K000007WEtDQAW (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Intercollegiate Athletics Budget. Eastern Washington University. Available online: https://inside.ewu.edu/intercollegiate-athletics-budget (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoln, Y.S. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; Volume 75. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. IJQHC 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeux, W.; Camel, S.; Douglas, C. Prevalence of food insecurity in collegiate athletes warrants unique solutions. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K. Food Insecurity, Academic and Athletic Performance of Collegiate Athletes Survey Research Paper. Master’s Thesis, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vento, K.A.; Delgado, F.; Skinner, J.; Wardenaar, F.C. Funding and college-provided nutritional resources on diet quality among female athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 1732–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauman, K.; Achen, R.; Barnes, J.L. The five most significant barriers to healthy eating in collegiate student-athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misener, P. Food Insecurity and College Athletes: A Study on Food Insecurity /Hunger among Division III Athletes. Ph.D. Thesis, State University, Binghamton, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey, E.L.; Brown, M.; Karpinski, C. Prevalence of food insecurity in the general college population and student-athletes: A review of the literature. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattangadi, N.; Vogel, E.; Carrol, L.J.; Cote, P. “Everybody I know is always hungry…but nobody asks why”: University students, food insecurity, and mental health. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.N.; Robinson, C.A.; Kerver, J.M.; Pivarnik, J.M. Diet quality of NCAA Division I athletes assessed by the Healthy Eating Index. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, T. Improving Health Programs for Seton Hill University First-Generation College Student-Athletes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hsuan, A.; Alger, A.; Giovanni, M.; Berman, T.; Silliman, K. Food insecurity among NCAA student athletes at a NCAA Division II university. J. Am. Coll. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, W.; Cianfrone, B.; Andrew, D. Show me the money! A review of current issues in the new NIL era. J. Appl. Sport. Manag. 2021, 13, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, L.; Scheyett, A. Who’s winning?: An examination of the characteristics of student athletes with high Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) valuation. Int. J. Sport. Soc. 2024, 15, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, Y.H. Understanding sport coaches’ turnover intention and well-being: An environmental psychology approach. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oglesby, L.W.; Gallucci, A.R.; Wynveen, C.J. Athletic trainer burnout: A systematic review of the literature. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, J. How do Lafayette athletes fuel up? The Lafayette. 13 September 2024. Available online: https://lafayettestudentnews.com/167495/sports/how-do-lafayette-athletes-fuel-up/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Big Sky Conference Strategic Plan: 2022–2027. Available online: https://bigskyconf.com/documents/2022/10/11//Strategic_Plan_Document_FINAL.pdf?id=7656 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

| Category | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SCHOOL PROFILES | ||

| Funding Source | Public | 12 (100.0) |

| Private | 0 (0.0) | |

| Geographic Location 1 | Urban (>60,000) | 8 (66.7) |

| Micro Urban (<60,000) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Rural (<50,000) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Size of Student Body 2 | Medium (<3000–9999) | 2 (16.7) |

| Large (≥10,000) | 3 (25.0) | |

| X-Large (>15.000) | 7 (58.3) | |

| Athletic Department 2022 Revenue 3 | 10–19 M | 6 (50.0) |

| 20–29 M | 5 (41.7) | |

| 30–39 M | 1 (8.3) | |

| PARTICIPANT DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Birth Sex | Male | 10 (37.0) |

| Female | 17 (63.0) | |

| Former Collegiate Athlete | Yes | 11 (40.7) |

| No | 16 (59.3) | |

| Profession | Athletic Administrator | 3 (11.1) |

| Athletic Trainer | 14 (51.9) | |

| Sports Performance Coach 4 | 4 (14.8) | |

| Sports Dietitian | 6 (22.2) | |

| Years in Profession | <1 year | 0 (0.0) |

| 1–3 years | 5 (18.5) | |

| 4–6 years | 7 (25.9) | |

| 7–10 years | 5 (18.5) | |

| >10 years | 9 (33.3) | |

| No response | 1 (3.7) | |

| Years in Current Position | <1 year | 4 (14.8) |

| 1–3 years | 12 (44.4) | |

| 4–6 years | 3 (11.1) | |

| 7–10 years | 4 (14.8) | |

| >10 years | 4 (14.8) | |

| Code | No. (%) * | Sample Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme #1: Financial | ||

| Limited finances | 17/27 (63.0) | “I think there are people missing meals because they just don’t have money.” (026) |

| Cost of living | 6/27 (22.2) | “When they run the numbers…they look at the dining halls, they base scholarship money on those numbers. It doesn’t necessarily translate to the expense of the community where they live…” (023) |

| Affordability of healthy food | 3/27 (11.1) | “I would say those international brands are probably going to be pricier products, too. So, they’re using more of their budget.” (009) |

| Resource distribution | 3/27 (11.1) | “…a handful of them don’t get stipends or other support.” (012) |

| Subtheme #2: Limited Life Skills | ||

| How to eat healthy | 15/27 (55.6) | “Another thing is lack of skills and knowledge about what is a healthy food.” (014) |

| Shopping and meal prep | 15/27 (55.6) | “They’re very motivated to want to cook healthier and shop healthier. But skills and finances impact how much they can really do and how much time they have to even learn about those things.” (020) |

| Money management | 12/27 (44.4) | “I think with skill-building opportunities, we should look at budgeting… one thing we could improve upon… is just talking about what… you should be putting your money towards, looking into how much those things actually cost, and what your budget would need to look like month to month in order to have a successful diet.”(022) |

| Time management | 10/27 (37.0) | “While I do agree with the competing priorities side of it, with practices and juggling everything, that’s more time management.” (026) |

| Subtheme #3: Competing Priorities | ||

| Balancing commitments | 7/27 (25.9) | “... just not having enough time because of having to go to the weight room, practice, class tutoring, and all that stuff. They just didn’t have time to fit in time to eat.” (019) |

| Eating is low priority | 7/27 (25.9) | “So, for them, it’s just balancing their schedule about what’s most important, I don’t have time to eat as much as I should or in that time frame.” (006) |

| Convenience | 4/27 (14.8) | “What I see most frequently is the selection of convenience foods instead of nutrient-dense foods.” (021) |

| Subtheme #4: Cultural (Food Preferences/Familiarity) | ||

| Stigma (− sentiment) | 12/27 (44.4%) | “I’ve had multiple times, where athletes approach me and ask me about food and snacks. The athletes rely more on us, the front-line people, rather than administration or their coaches, because there’s just a stigma about it.” (028) |

| Stigma(+ sentiment) | 6/27 (22.2%) | “I feel more and more that not just among the student-athletes, but even among the general population of students, there’s less stigma around the food security resources. I feel like students are way more open to it.” (019) |

| Socio-economics | 8/27 (29.6) | “I have my group... it could be socioeconomic. Because the foods that they eat at home may not be the healthiest. And that’s just all they’re used to eating.” (009) |

| Personal identity | 7/27 (25.9) | “I see American, European, and Asian students are way different with what they choose as a meal. And then also, balance and nutrition are way different…” (014) |

| Code | No. (%) * | Sample Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme #1: Financial | ||

| Budget | 10/27 (37.0) | “I think finances are the biggest problem... as budget cuts come around … food is, unfortunately, the first thing to go as finances are limited.” (027) |

| Insufficient stipend | 9/27 (33.3) | “The hardest thing for me is the difference between our headcount or full-ride athletes and those that are on equivalency, all the way to those that are walk-ons… I do think there’s a big difference for students who are getting a stipend every month to pay for their room and board, versus those who are on equivalency and maybe just having their books covered. There’s just a big disparity between the resources they have to buy food.” (023) |

| Resource distribution | 8/27 (29.6) | “For us, it’s probably more team by team within athletics… what’s the budget for each team? What can they afford to do?” (007) |

| Cost of food | 3/27 (11.1) | “…food is, unfortunately, the first thing to go as finances are limited” (027) |

| Subtheme #2: Competing Priorities | ||

| Eating is low priority | 10/27 (37.0) | “We’ve really, really, really tried to build up our fueling center… Some coaches have different philosophies about dipping into their sports accounts to help fund their fueling station…” (026). |

| Inadequate fueling station funds | 8/27 (22.2) | “I left the [my previous] university… in December of last year, and…they just had a room that was open, and it was like, “This is your fueling station.” But really, it was snacks from Costco. It wasn’t even full of food…” (010) |

| Nutrition programs, hiring a dietitian is low priority | 5/27 (18.5) | “We’re missing a Director of Sports Nutrition. It’s a huge piece that we’re missing, having somebody to direct this effort and all these inner workings and for someone to align it all. Hire a dietitian or two. That would be super cool.” (019) |

| Subtheme #3: Cultural | ||

| Dept. culture (+ sentiment) | 6/17 (22.2) | “…our student-athletes need more accessibility to food and we’re trying to push that... We’ve started stocking areas, especially high traffic areas like our weight room…we are looking for a fueling station…it has been a huge push for us… we’ve identified an area that our student-athletes need and we’re trying to move in the right direction” (008) |

| Dept. culture (− sentiment) | 5/27 (18.5) | “The biggest frustration… as an athletic trainer, I did not have the administrative support from a lot of key individuals… I’d say with nutrition, they didn’t see the investment and the payoff for buying more food…” (026) |

| Code | No. (%) * | Sample Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme #1: Financial | ||

| Quality of options | 10/27 (37.0) | “Another one is the quality of our dining hall…They always complain about the quality, and so they don’t choose to eat there when it is a resource on campus.” (006) |

| Insufficient stipend | 9/27 (33.3) | “We probably have the most resources available to us with our football team, but we run into the same issues. The cost of living in our town has got ridiculous. I don’t think their stipend checks are enough to cover what they need…the majority is going to rent…they’re trying to stretch the limited funds they have left.” (024) |

| Cost of living | 4/27 (14.8) | “The cost of living in our town has gotten ridiculous. I don’t think their stipend checks are enough to cover what they actually need.” (024) |

| Subtheme#2: Competing Priorities (Food Environment Reflects Eating is Low Priority) | ||

| Availability | 7/27 (25.9) | “…the second thing I noticed is practice times occur when our dining halls are open. We run into a lot of issues on the weekend… dining may not open until 11 or 12 o’clock. You know that day that getting breakfast is a big challenge.” (002) |

| Access/proximity | 4/27 (14.8) | “…the international aspect is something that could be added…I feel like food insecurity impacts them in a different way. They have the finances, but they just feel like they don’t have access to the same things here as they do at home.” (012) |

| Subtheme#3: Cultural/Societal | ||

| Socio-economics | 4/27 (14.8) | “It’s a small community. It’s getting very expensive, and I think some of our other institutions are running into this, too. I don’t know how people live off campus and can afford rental and car insurance and food. I really don’t.” (026) |

| Stigma | 4/27 (14.8) | “they’re afraid they’ll be stigmatized if they ask for that type of assistance” (002) |

| School culture | 3/27 (11.1) | “Honestly… the athletic department is trying to solve this problem by themselves. The school should do more… if they want to provide better service for student-athletes and other students as well.” (014) |

| Social media, advertising | 2/27 (7.4) | “I think spending a lot of money on supplements …they buy these supplements for $100 instead of making a grocery run…they think they are making a decision that is important for their performance, but had they just spent that money on food, they would have seen a better impact.” (005) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gordon, B.; Christensen, N.; Reader, J. Systemic Factors Fuel Food Insecurity Among Collegiate Student-Athletes: Qualitative Findings from the Running on Empty Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142254

Gordon B, Christensen N, Reader J. Systemic Factors Fuel Food Insecurity Among Collegiate Student-Athletes: Qualitative Findings from the Running on Empty Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(14):2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142254

Chicago/Turabian StyleGordon, Barbara, Natalie Christensen, and Jenifer Reader. 2025. "Systemic Factors Fuel Food Insecurity Among Collegiate Student-Athletes: Qualitative Findings from the Running on Empty Study" Nutrients 17, no. 14: 2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142254

APA StyleGordon, B., Christensen, N., & Reader, J. (2025). Systemic Factors Fuel Food Insecurity Among Collegiate Student-Athletes: Qualitative Findings from the Running on Empty Study. Nutrients, 17(14), 2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142254