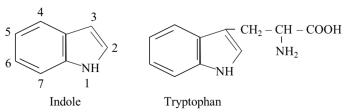

Serotonin, Kynurenine, and Indole Pathways of Tryptophan Metabolism in Humans in Health and Disease

Abstract

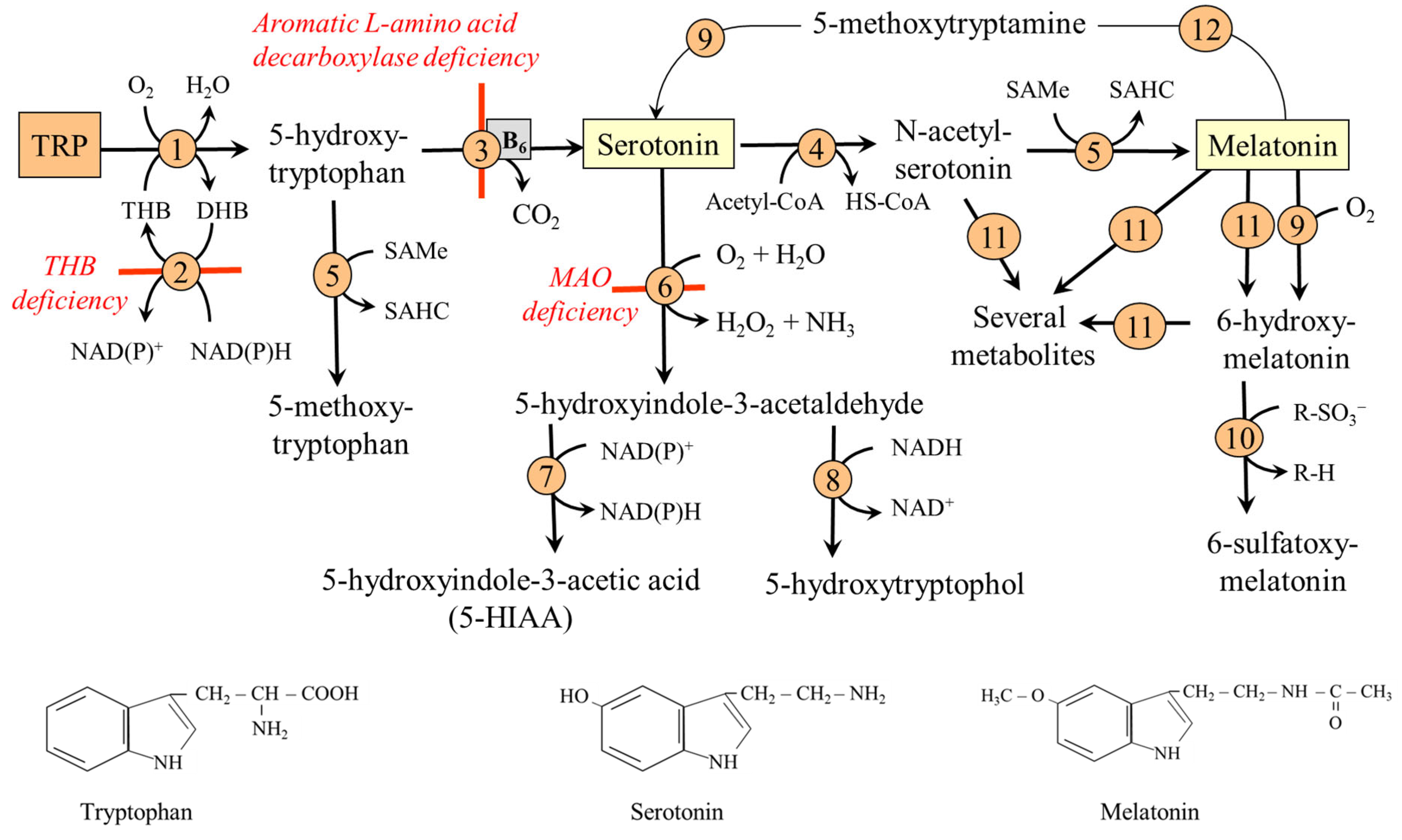

1. Introduction

2. Biochemical Properties of Tryptophan

2.1. TRP Sensitivity to Oxidative Stress and Antioxidative Properties of TRP

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of TRP

2.3. TRP and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR)

2.4. TRP and Pregnane X Receptor (PXR)

3. Sources, Requirements, and Transport of Tryptophan in the Blood and Through the Plasma Membrane

3.1. Sources of TRP

3.2. Nutritional Requirements

3.3. TRP Transport in the Blood

3.4. TRP Transport Through the Plasma Membrane

Hereditary Disorders of TRP Transport Through the Plasma Membrane

- Hartnup’s disease—a disorder of transport of TRP and other LNAA in the proximal tubules of the kidney and small intestine due to a mutation in SLC6A19 (B0AT1). It is clinically manifested by aminoaciduria and symptoms of pellagra, which respond to therapy with niacin, but not to TRP administration [17].

- Drummond’s (blue diaper) syndrome—a rare disease caused by a disorder of TRP resorption in the small intestine due to TAT1 (SLC16A10) mutation. The result is increased TRP degradation by the intestinal microbiota into indole and excretion of indican in the urine [37].

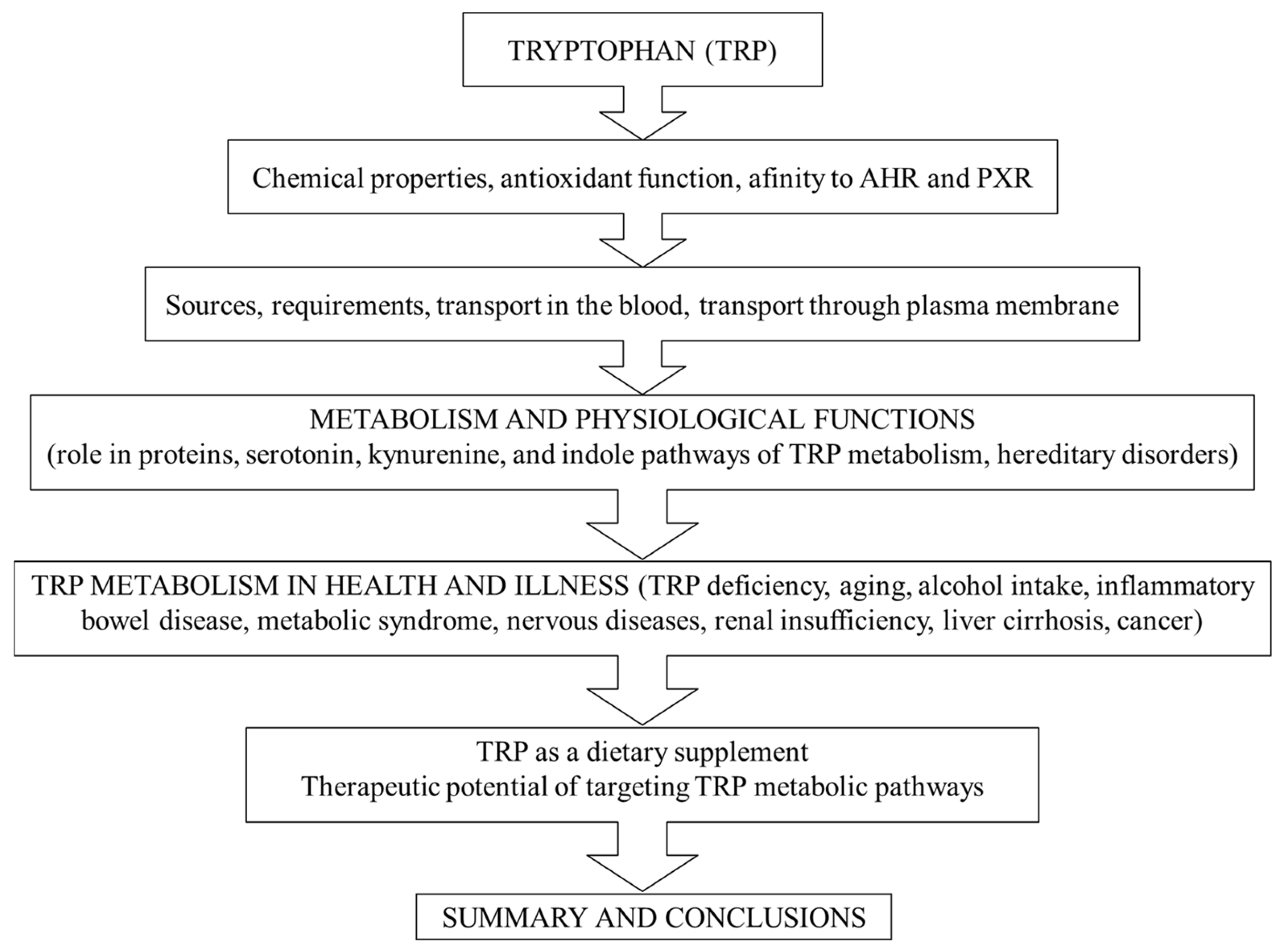

4. The Pathways of Tryptophan Metabolism

5. Tryptophan and Proteins

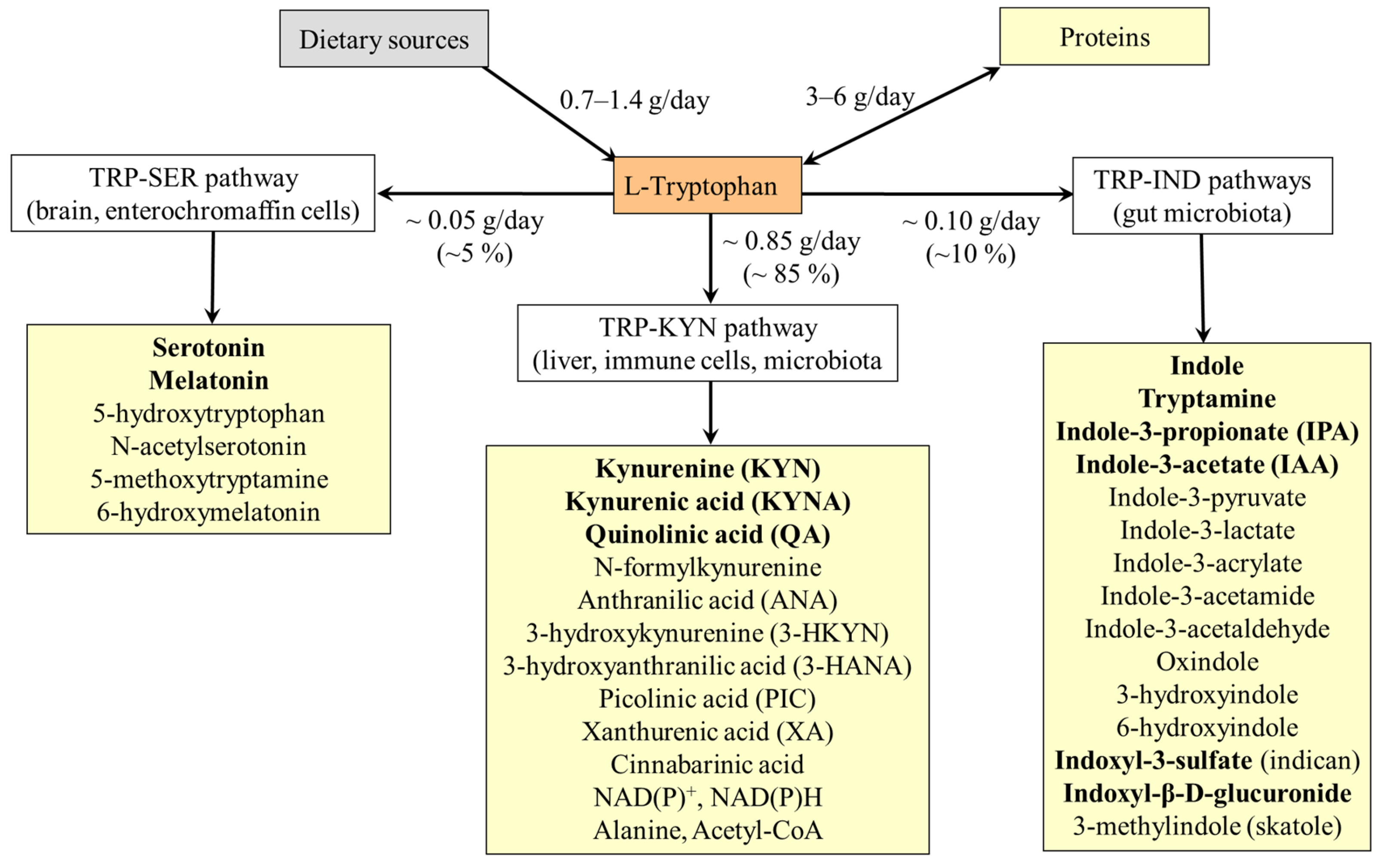

6. TRP-SER Pathway and Physiologic Role of Serotonin and Melatonin

6.1. TRP-SER Pathway

6.1.1. Serotonin Degradation

6.1.2. Melatonin Degradation

6.1.3. Hereditary Disorders of the TRP-SER Pathway

- Tetrahydrobiopterin (THB) deficiency. THB is required as a cofactor of phenylalanine hydroxylase, tyrosine hydroxylase, and TRPH. Defects in the biosynthesis of THB lead to deficiencies of dopamine and serotonin in the central nervous system. The most common cause is a deficiency of dihydrobiopterin (DHB) reductase, which is required to convert DHB back into THB. The symptoms include low muscle tone, movement disorders, impaired thermoregulation, and neurological, behavioral, and developmental problems. Treatment consists of THB supplementation and replacement therapy with catecholamines (L-DOPA) and serotonin precursors [60].

- Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. A rare autosomal recessive disorder leading to a combined deficiency of dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and serotonin. The main clinical symptoms, which typically emerge in the first months of life, include hypotonia, hypokinesis, autonomic dysfunction, and developmental delay [61].

- MAO-A deficiency. MAO-A deficiency (Brunner syndrome) is a rare disorder characterized by elevated levels of monoamines, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the brain, and reduced urinary levels of 5-HIAA and vanillylmandelic acid. Symptoms include intellectual disability, obsessive behavior, and episodic explosive aggression, flushing, headaches, and diarrhea [56].

6.2. The Role of Serotonin

6.2.1. Serotonin and the Brain

6.2.2. Serotonin and the Gut

6.2.3. Other Serotonin Effects

6.3. The Role of Melatonin

6.3.1. Melatonin and the Control of Circadian Rhythm

6.3.2. Melatonin as an Antioxidant

6.3.3. Other Melatonin Effects

7. TRP-KYN Pathway and Its Physiologic Importance

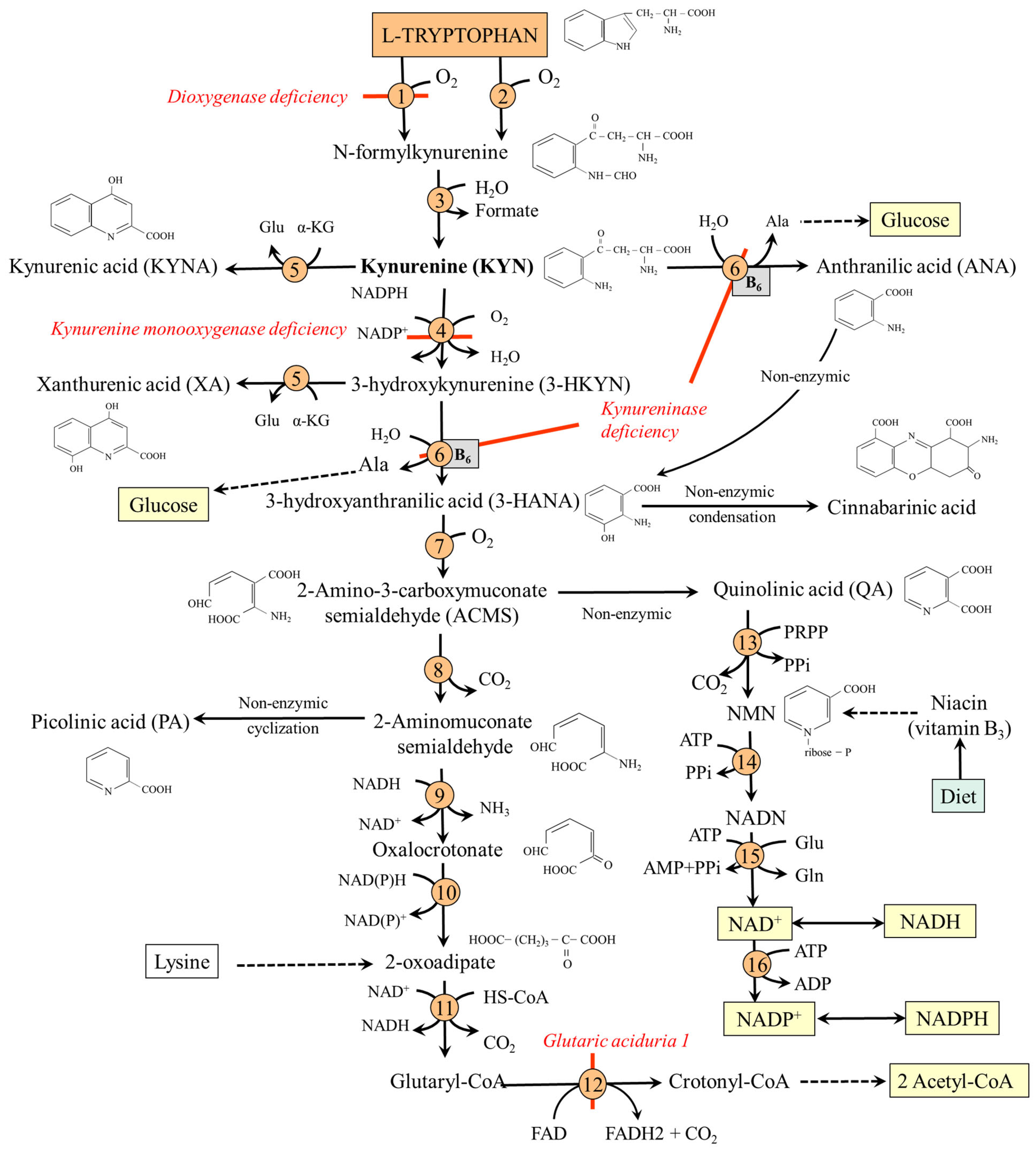

7.1. TRP-KYN Pathway

- (i)

- (ii)

- Synthesis of anthranilic acid (ANA) by kynureninase, which enables the bypass of the formation of 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HKYN).

- (iii)

- 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate-6-semialdehyde (ACMS) synthesis through 3-HKYN and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HANA). The ACMS has two possible routes. First, non-enzymic conversion to quinolinic acid (QA), which is used by quinolinate phosphoribosyl transferase (QPRT) to form nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NMN), the precursor of NAD+ and NADP+. Second, decarboxylation to 2-aminomuconate-6-semialdehyde, which can be spontaneously converted to picolinic acid (PA), or oxidized via a sequence of reactions, shared with the lysine degradation pathway, to form two molecules of acetyl-CoA. Because TRP degradation through the TRP-KYN pathway yields acetyl-CoA and alanine, TRP is classified as both a glucogenic and a ketogenic amino acid (Figure 4).

Hereditary Disorders of the TRP-KYN Pathway

- TDO deficiency. The first human case without negative clinical consequences was described in 2017 [87]. Increased levels of TRP and serotonin characterize the biochemical phenotype.

- Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase deficiency. The disorder leads to the accumulation of KYN and a shift within the TRP-KYN pathway toward KYNA and ANA. The disease is associated with cognitive deficits [88].

- Kynureninase deficiency (hydroxykynureninuria). It results in decreased synthesis of nicotinic acid mononucleotide and signs of pellagra. After TRP loading, patients excrete excessive amounts of XA, KYNA, 3-HKYN, and KYN [81].

- Glutaric aciduria 1. A rare autosomal recessive disease caused by glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. There is an increase in the levels of TRP and glutaryl-CoA derivatives, such as glutaric acid and glutarylcarnitine, and secondary carnitine deficiency. Increases also the concentration of lysine, which is also catabolized via glutaryl-CoA [89]. There is a risk of intellectual disability. Carnitine and choline supplementation, along with reduced lysine, TRP, and protein intake, is recommended [90].

7.2. Physiological Importance of the TRP-KYN Pathway

7.2.1. The TRP-KYN Pathway and the Control of TRP Level in the Body

7.2.2. The TRP-KYN Pathway and Nicotinamide Nucleotide Synthesis

7.2.3. The TRP-KYN Pathway and the Immune System

- Increased levels of KYN, PA, and QA inhibit the proliferation of T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells [101].

- In piglets, 3-HKYN and 3-HANA have been shown to prevent allograft rejection and tubular injury in kidney transplantation [102].

- TRP depletion in a tissue due to increased flux through the TRP-KYN pathway induces, via a nutrient-sensing system termed the general control non-derepressable 2 (GCN2), proliferative arrest of cytotoxic T cells [103].

- KYN, 3-HKYN, and some of their derivatives protect the lens and the retina from UV irradiation. Their spontaneous deamination and binding to lens proteins contribute to age-related cataract [106].

7.2.4. The TRP-KYN Pathway and the Nervous System

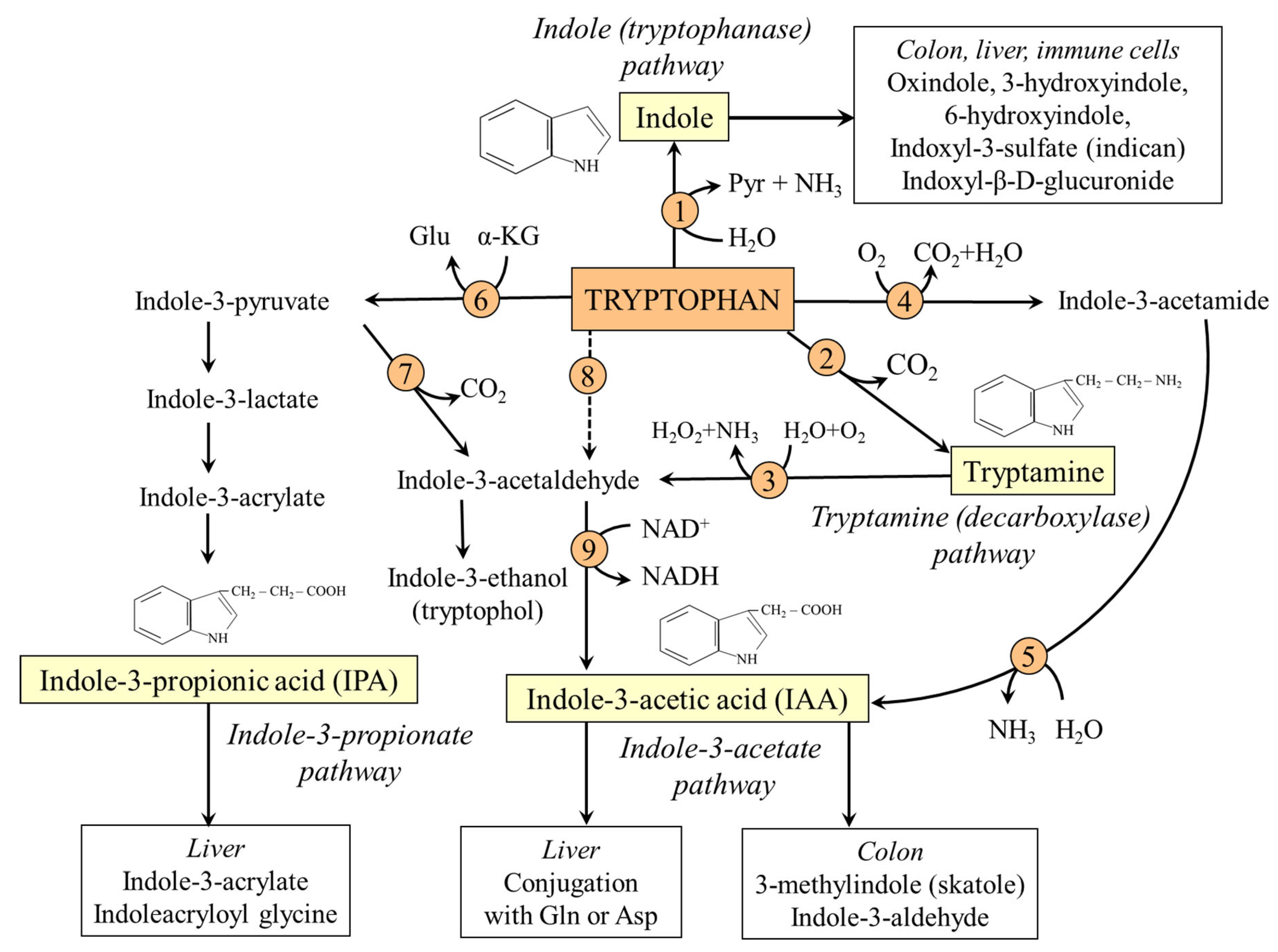

8. TRP-IND Pathways

8.1. Tryptophanase (Indole) Pathway

8.2. Decarboxylation (Tryptamine) Pathway

8.3. Indole-3-Propionate Pathway

8.4. Indole-3-Acetate Pathway

9. Alterations in Tryptophan Metabolism Under Different Physiological and Pathological Conditions

9.1. Dietary TRP Deficiency

- TRP-SER pathway. In rats, administration of a TRP-free amino acid mixture resulted in a sharp drop in blood TRP and decreased levels of TRP, serotonin, and 5-HIAA in the brain [123]. In humans, the TRP-free amino acid mixture caused, within 4 h after ingestion, a substantial decrease in plasma TRP associated with depression and anxiety [64]. In a study examining the differences in anxiety, depression, and mood in healthy adults after consuming a high and a low TRP diet for four days each, a diet with high content of TRP resulted in fewer depressive symptoms and decreased anxiety [124]. In summary, the lack of TRP in the body can result in depression and anxiety due to insufficient serotonin production in the brain [125,126].

- TRP-KYN pathway. The TRP-KYN pathway is an important source of nicotinamide nucleotides. Prolonged deficiency of TRP and niacin (vitamin B3, i.e., nicotinic acid and nicotinamide), also referred to as vitamin PP (pellagra preventive), results in pellagra, the photosensitive disease that has been common in populations where corn was the staple food. Maize contains low amounts of TRP, and the majority of niacin is bound to polysaccharides as niacytin, which cannot be hydrolyzed by the mammalian digestive system [17]. The main symptoms of pellagra are described as the “3 Ds”: dementia, diarrhea, and dermatitis. New corn varieties have higher levels of both niacin and TRP. The symptoms of pellagra have also been observed in cases of non-nutritional origin of TRP deficiency, e.g., Hartnup’s disease (Section “Hereditary Disorders of TRP Transport Through the Plasma Membrane”) and carcinoid, serotonin-producing tumor originating from ECC [17].

- TRP-IND pathway. Experimental studies have clearly demonstrated that TRP dietary deficiency leads to dysbiosis, which in turn promotes the development of health problems in the host. In rats, a TRP-free diet decreased IPA concentration in stool and blood [127]. In a mouse model, TRP deficiency induced gut microbiota dysbiosis, altered the formation of various gut metabolites and expression of regulatory T-lymphocytes, and increased proinflammatory cytokine levels [128,129].

9.2. TRP and Aging

- TRP-SER pathway. Significant alterations occur in melatonin synthesis. Melatonin levels decline gradually over the lifespan and may be related to decreased sleep efficacy, as well as to the deterioration of many circadian rhythms and antioxidant defense [76]. Therefore, melatonin supplementation should be considered in the elderly.

- TRP-KYN pathway. Aging is associated with increased activity of the TRP-KYN pathway due to upregulated cortisol production, an activator of TDO, and the presence of proinflammatory cytokines, which induce IDO [80]. A trend toward reduced TRP and increased kynurenine levels, primarily KYN, KYNA, and QA, has been observed in serum and CSF in older individuals [130]. Kynurenines are supposed to play a role in alterations in cognitive function and depression in aging [130]. For these reasons, it is unclear whether TRP supplementation should be recommended in old age, even though TRP levels tend to decline. In addition, a causal link between downregulation of KYN formation and lifespan prolongation in vertebrates has been suggested [131].

- TRP-IND pathways. Aging and age-related disorders are influenced by substances of gut microbiota origin that appear in the blood, such as endotoxins, ammonia, and indoles. Some indole derivatives, particularly IPA, cross the BBB and exert neuroprotective effects [132,133]. In muscles, indoles can slow the progression of sarcopenia, i.e., the loss of skeletal muscle associated with aging, by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, which activate proteolysis and amino acid oxidation [134,135]. Therefore, the gut microbiome is a target of studies examining the possibility of optimizing its composition to form beneficial metabolites and slow down the development of undesirable consequences of aging [136,137,138].

9.3. TRP and Alcoholism

- TRP-SER and TRP-KYN pathways. Acute alcohol intake activates TDO and TRP degradation via the TRP-KYN pathway in the liver, reducing circulating TRP availability to the brain and decreasing serotonin and melatonin synthesis [139]. Serotonin deficit may contribute to alcohol-induced aggression, depression, and impaired memory. The suppression of melatonin synthesis contributes to the development of sleep disorders [140].Alterations in TRP metabolism probably also play a role in a variety of neuropsychiatric symptoms in individuals who try to abstain from alcohol. In rats fed an ethanol-containing diet, alcohol withdrawal increased corticosterone concentrations associated with TDO activation, resulting in decreased concentrations of TRP and serotonin synthesis in the brain [141]. A recent study performed at the 5th and 10th day after alcohol withdrawal in patients with alcohol-use disorder demonstrated increased KYN/TRP ratio and QA concentration, which exerts neurotoxic effects, but not KYNA, which possesses neuroprotective properties [142]. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that the disruption of TRP metabolism contributes to alcohol-related neuropathy and myopathy, which is frequent in subjects who consume alcohol chronically [143].

- TRP-IND pathways. Alcohol consumption alters microbiota composition, TRP metabolism through the TRP-IND pathway, and host immunity. Dysbiosis and decreased intestinal levels of IAA have been observed in chronic-binge ethanol-fed mice, which were associated with reduced production of interleukin-22 by innate lymphoid cells in intestinal lamina propria [4].

9.4. TRP and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- TRP-SER pathway. Upregulation of ECC number and TRPH1 expression, as well as increased gut and plasma serotonin levels, have been demonstrated in patients with IBD [144,145,146]. Decreased expression of the serotonin transporter is likely also a contributing factor to increased mucosal serotonin signaling [146,147]. Pharmacological blocking of 5-HT receptors and peripheral serotonin synthesis using a TRPH inhibitor has been shown to attenuate intestinal inflammation in experimental models [145,148,149].

- TRP-KYN pathway. Increased expression of IDO1 in colonic biopsies and elevated levels of kynurenines, primarily QA, have been demonstrated in patients with IBD. Since QA exhibits proinflammatory properties, its increase may contribute to disease exacerbation [150].

- TRP-IND pathways. Unlike serotonin and KYN metabolites, some researchers suggest that indole metabolites may hold therapeutic potential [151]. IPA has been shown to suppress experimental colitis in mice [152]. Indole-3-carbinol, an indole derivative found in vegetables, has been found to prevent colitis in mice [153]. Studies in murine and porcine models of colitis demonstrated that TRP supplementation enables, via AHR, the homing of regulatory T cells to the large intestine and reduces the risk of colitis [154,155]. Taken together, the findings suggest that TRP administration, accompanied by a simultaneous adjustment of the microbiome to favor indole production, can have a therapeutic effect.

9.5. TRP and Metabolic Syndrome

- TRP-SER pathway in the periphery. Gut-derived serotonin is an important driver of the development of metabolic syndrome. Serotonin can promote obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by stimulating insulin secretion, inhibiting thermogenesis in beige adipose tissue, and increasing lipogenesis in white adipose tissue and the liver [71,72]. Increased serotonin formation, resulting from higher ECC density and TRPH1 expression in the small intestine, has been demonstrated in rodent models of obesity [157,158]. In humans, elevated serotonin concentrations have been reported in hypertension, atherosclerosis, and arterial thrombosis [159]. TRPH inhibitors that decrease peripheral serotonin synthesis are being investigated in the treatment of diseases associated with metabolic syndrome [50,160].

- TRP-SER pathway in the brain. In the brain, the flux through the TRP-SER pathway decreases somewhat due to decreased TRP availability [161,162,163]. The cause is not a decrease in plasma TRP level but rather an increase in BCAAs, which compete with TRP for the L-transporter. The BCAA level increases due to insulin resistance [30]. The consequences of decreased flux through the TRP-SER pathway in the brain may include sleep and diurnal rhythm disorders, depression, increased food intake, and decreased energy expenditure. A systematic review and meta-analysis have demonstrated that short sleep duration is associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome [161]. Other studies have demonstrated that increased dietary TRP intake had beneficial effects on sleep duration and plasma biomarkers of metabolic syndrome [162].

- TRP-KYN pathway. The flux through the TRP-KYN pathway increases due to IDO1 induction by chronic inflammation. Increased levels of KYN metabolites or KYN/TRP ratio have been observed in most disorders associated with metabolic syndrome, including obesity [163,164,165], T2DM [166], and cardiovascular events [167].

- TRP-IND pathways. Studies in subjects with metabolic syndrome have demonstrated decreased levels of indole and its derivatives in plasma and feces, a shift from the TRP-IND to the TRP-KYN pathway in the gut, and intestinal inflammation and disruption of the intestinal barrier [136,165]. It has been suggested that decreased levels of IPA, which exerts benefits on gut homeostasis through AHR and PXR, can predict the risk of NAFLD, T2DM, and cardiovascular disease [168].

9.6. TRP and Diseases of the Nervous System

- TRP-SER pathway. Serotonin depletion is the leading cause of a mental disorder, referred to as major depressive disorder, characterized by chronically pervasive low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest in usual activities [169,170]. The cause of decreased flux through the TRP-SER pathway is likely IDO1 activation in microglia, driven by neuroinflammation, leading to decreased TRP availability for serotonin synthesis. The consequence is also a decreased formation of N-acetylserotonin and melatonin, resulting in disturbances in sleep, increased vulnerability of the central nervous system to oxidative stress, and the development of neurodegenerative diseases [169].

- TRP-KYN pathway. Neuroinflammation and subsequent IDO1 activation by various inflammatory mediators play a pivotal role in dysregulating the TRP-KYN pathway in most diseases of the nervous system. Decreased levels of KYNA and increased QA, or a decreased KYNA-to-QA ratio, in CSF, brain, or plasma have been reported in Alzheimer’s disease [130], Parkinson’s disease [130,171], Huntington’s disease [172], and multiple sclerosis [173,174,175]. Post-mortem studies revealed significantly increased activity of 3-HANA dioxygenase and elevated levels of QA in the cortex and striatum of patients with Huntington’s disease [176]. KYNA negatively correlated with depression severity and significantly increased after therapy [170].Unlike the decreased KYNA to QA ratio in depression and neurodegenerative diseases, elevated levels of KYNA probably play a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Increased KYNA levels and downregulated kynurenine 3-monooxygenase gene expression have been found in the brains of people with schizophrenia [177,178,179]. The hypothesis aligns with a theory that the hypofunction of NMDA receptors is a component of the disease’s pathophysiology [180].

- TRP-IND pathways. Several investigators have demonstrated that indoles produced by gut microbiota from TRP play a role in the development and function of the nervous system, as well as in the pathogenesis of its diseases [117,132,133]. It is assumed that most naturally occurring indoles in the blood enter the brain and exert neuroprotective effects, primarily by mitigating oxidative stress [133]. Special attention is focused on IPA, which acts as a free radical scavenger and an anti-inflammatory substance, thereby decreasing the production of proinflammatory cytokines [117].

9.7. TRP and Chronic Renal Insufficiency

- TRP levels and the TRP-SER pathway. Decreased total and protein-bound TRP levels are found in subjects with CRI. In contrast, concentrations of free TRP are usually increased or unaltered due to TRP replacement at the binding site of albumins by uremic toxins [112,186]. An important alteration in aminoacidemia is a decrease in the concentration of most essential amino acids, primarily BCAA (valine, leucine, and isoleucine), due to acidosis-induced oxidation in muscles [187]. An increased free TRP to BCAA ratio can enhance TRP entry into the brain and serotonin production, and play a role in uremic anorexia [188].

- TRP-KYN pathway. The activation of TDO and IDO1 by cortisol and proinflammatory cytokines, as well as impaired renal function, are the leading causes of elevated kynurenine levels in patients with uremia [189]. A role also plays the suppression of QA utilization in NAD+ synthesis, as demonstrated in kidney biopsies from patients with CRI [190]. The kynurenines recognized as uremic toxins include KYN, KYNA, ANA, 3-HKYN, 3-HANA, and QA. However, their role in uremia is poorly understood. Relatively well-documented is the brain toxicity of QA [182,191,192]. Experiments conducted in vitro also indicate that QA inhibits erythropoietin gene expression, contributing to the pathogenesis of uremic anemia [193]. Experimental studies indicate increased entry of some kynurenines into the brain due to the BBB disruption. In rats with CRI, plasma and brain TRP levels were decreased, while KYN and 3-HKYN levels were elevated [194].

- TRP-IND pathways. Concentrations of both free and protein-bound indole metabolites, primarily IAA, indoxyl sulfate, and indoxyl-β-D-glucuronide, recognized as uremic toxins, increase in patients with CRI due to impaired gut barrier integrity and their decreased elimination in urine [112,113]. Unlike the positive influence of most indole derivatives in the gut, IAA, indoxyl sulfate, and indoxyl-β-D-glucuronide act in cells of the cardiovascular system as pathogenic agents that, via the AHR, induce the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines, apoptosis, and oxidative stress. Their increased concentrations correlate with cardiovascular events, such as atherosclerosis and thrombosis [113,195]. The therapeutic potential of orally administered spherical carbon adsorbent AST-120 is investigated, which reduces the absorption of indoles from the gut and indoxyl-sulfate levels in plasma [196].

9.8. TRP and Liver Cirrhosis

- TRP levels and the TRP-SER pathway. An increased concentration of free TRP is a well-documented finding in patients with liver cirrhosis [26,197]. Primary causes are impaired TRP catabolism via the TRP-KYN pathway in the liver, due to reduced hepatocyte mass and portacaval shunts. A role has also decreased the amount of albumin-bound TRP as a result of hypoalbuminemia and increased concentration of free fatty acids and indoles, which compete with TRP for the binding site. On the other hand, the BCAA level (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) in cirrhosis decreases due to their extensive use for ammonia detoxification to glutamine in muscles [198,199]. Because TRP and BCAA share the same carrier, an increased TRP-to-BCAA ratio enhances TRP availability for serotonin synthesis in the brain. It may contribute to the pathogenesis of anorexia and poor nutritional status in some patients [29,35,36]. There is probably no direct relationship between TRP levels and encephalopathy. Oral TRP load increased plasma TRP levels but did not induce or worsen signs of hepatic encephalopathy [200].

- TRP-KYN pathway. Increased concentrations of kynurenines, primarily due to extrahepatic IDO1 induction, have been found in plasma and CSF in patients with liver disease [203,204]. Their role in cirrhosis is controversial. There are reports that the immunosuppressive effects of some kynurenines protect against viral hepatitis and reduce oxidative stress and inflammation. On the other hand, immunosuppression can contribute to multiorgan damage and promote the development of nosocomial infections and carcinogenesis [204,205,206]. A growing body of evidence suggests that neuroinflammation and TRP-KYN pathway dysregulation contribute to the pathogenesis of encephalopathy. Increased production of neurotoxic metabolites, 3-HKYN and QA, has been observed in animal models and in humans with hepatic encephalopathy [203,207,208].

- TRP-IND pathways. Disrupted intestinal barrier integrity and dysbiosis, usually overgrowth of pathogenic genera Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and Enterobacter are common findings in subjects with liver cirrhosis [137,209]. The result is increased entry of indoles and other microbial products, such as ammonia and endotoxin, into portal circulation. The inability of the cirrhotic liver to clear such compounds results in their increased levels in systemic circulation and influence on the host. It is a consensus that dysbiosis and “leaky gut syndrome” are risk factors for decompensation of the hepatic disease. Unfortunately, data on the amounts and spectrum of indoles formed in the gut in cirrhosis are absent, and their effects on the pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis are not entirely clear. It has been shown that oxindole, formed in the liver from indole by cytochrome P450, crosses the BBB and is apparently involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy [210,211].

9.9. TRP and Cancer

- TRP-SER pathway in the brain. Studies in subjects with cancer demonstrated both decreased and increased plasma concentrations of free TRP, suggesting alterations in its entry into the brain and serotonin synthesis, which can play a role in behavior, mental functions, and onset of anorexia-cachexia syndrome [212,213,214,215].

- TRP-SER pathway in the periphery. Serotonin has been shown to activate cancer cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration, and angiogenesis in various types of cancer [215,216,217]. The carcinogenic effect is mediated primarily through autocrine serotonin signaling affecting various types of 5-HT receptors depending on the type and stage of cancer [217]. For example, increased expression of TRPH1 and 5-HT7 receptors has been reported in breast cancer [216]. Furthermore, serotonin activates RhoA/ROCK/YAP signaling and promotes colon carcinogenesis via serotonylation [218]. In contrast to the carcinogenic potential of serotonin, 5-methoxytryptophan, a byproduct of the TRP-SER pathway, referred to as cytoguardin (see Figure 3 and Section 11.1), likely acts against cancer growth [219,220].In connection with the role of the TRP-SER pathway in cancer, carcinoid, a tumor originating from the ECC, that produces 5-hydroxytryptophan and serotonin, should be mentioned. Clinical manifestations include decreased TRP levels, signs of pellagra due to reduced synthesis of nicotinamide nucleotides via the TRP-KYN pathway, paroxysmal facial flushing, diarrhea, bronchospasm, and heart valve disease. A part of the therapy is the TRPH1 inhibitor, teloristat ethyl [62].

- TRP-KYN pathway. Increased expression of IDO1 and TDO, as well as increased activity of the other enzymes in the TRP-KYN pathway, have been reported in various types of cancer, including breast, stomach, colon, pancreatic, and lung cancers [214,221,222]. Notably, QPRT, the enzyme directing the TRP-KYN pathway towards NAD+ generation, was upregulated in invasive breast cancer and aggressive glioblastomas [98].It is a consensus that increased kynurenine formation contributes to immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment, as well as neovascularization, tumor growth, and metastasis [11]. The progression of cancer also promotes systemic immune suppression, primarily resulting from the upregulation of IDO1 by host dendritic cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes [223]. The mechanism by which cancer-induced TRP catabolism leads to immunosuppression in the host is unclear; the role of Treg lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) has been hypothesized [224]. Preclinical models have demonstrated that inhibiting IDO1, TDO, and kynurenine 3-monooxygenase can enhance the efficacy of cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy in various types of cancer [214,222,225].

- TRP-IND pathways. Our understanding of the role of indole derivatives in cancer remains limited. Several experimental studies indicate their cytostatic and preventive effects [226,227,228]. For example, an AHR agonist, indole-3-carbinol, decreased viability and accelerated apoptosis in cultures of human colorectal carcinoma cell lines [228].

10. Tryptophan as a Dietary Supplement

Risks and Side Effects of TRP Administration

11. Therapeutic Possibilities of Targeting Individual Pathways of Tryptophan Metabolism

11.1. Targeting the TRP-SER Pathway

- 5-Hydroxytryptophan. 5-hydroxytryptophan, the intermediate in the TRP-SER pathway, crosses the BBB, and, unlike TRP, it cannot be shunted into niacin or protein synthesis. Its administration can affect serotonin levels in both the brain and the periphery. It has shown good therapeutic potential for depression therapy when used with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [238,239]. Positive effects have also been reported in the treatment of headaches, fibromyalgia, anxiety, insomnia, and as an anorectic [238,239].

- Melatonin. Melatonin is both water- and lipid-soluble (‘amphiphilic’) and can freely cross plasma membranes, including the BBB. Therefore, melatonin and several melatonin analogues (e.g., ramelteon, agomelatine, and tasimelteon) are currently used to treat sleep disorders, prevent desynchronosis (jet lag), as an antioxidant, and in other conditions [76]. Current evidence shows that melatonin protects against liver injury and inhibits the progression of liver cirrhosis [240]. The recommended dose has not been clearly established and varies from units to hundreds of mg daily [76,241].

- N-acetylserotonin (normelatonin). N-acetylserotonin, the intermediate in endogenous synthesis of melatonin from serotonin, and its derivative N-(2-(5-hydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl) ethyl)-2-oxopiperidine-3-carboxamide (HIOC) act as agonists of melatonin receptors and potent antioxidants. Both are investigated as potential therapeutic agents for brain injury, autoimmune encephalomyelitis, ischemic encephalopathy, and other diseases [242].

- 5-methoxytryptophan. 5-methoxytryptophan, also called cytoguardin, is synthesized by 5-hydroxytryptophan methylation in fibroblasts and endothelial cells. It inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) transcription, an enzyme involved in the conversion of arachidonic acid to various prostaglandins, induced by diverse proinflammatory and mitogenic factors. Cytoguardin has been shown to defend against inflammation-mediated tissue damage and fibrosis. In contrast to serotonin, cytoguardin exerts anticancer effects and has the potential to be a therapeutic agent for certain types of cancer [219,220].

- TRPH inhibitors. The suppression of serotonin synthesis by administering TRPH inhibitors is promising in the treatment of several diseases, including cancer, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic syndrome, NAFLD, fibrotic diseases, and cardiovascular diseases [50,51,145,160]. The investigation is focused on inhibitors that decrease serotonin synthesis but cannot cross the BBB. The first TRPH inhibitor approved by the FDA for therapy of diarrhea, cutaneous flushing, and bronchoconstriction due to carcinoid syndrome has been teloristat ethyl [62].

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRIs, such as fluvoxamine, sertraline, and citalopram, increase the concentration of serotonin in nerve synapses and are recognized as primary antidepressant drugs [239,243]. Controversial data exist regarding the use of SSRIs in cancer therapy [62]. The use of SSRI is associated with increased risk of bleeding, especially intracranially and in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The probable cause is decreased uptake of serotonin by thrombocytes from plasma, leading to impaired function [243].

- Tetrahydrobiopterin (THB). THBs are enzymatic cofactors required for the hydroxylation of AAA, including TRP, and NO synthesis. THB exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and has been suggested as a candidate drug for the therapy of cognitively impaired patients experiencing metabolic disorders and nervous system diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease [60,244].

- 5-HT receptor ligands. Several agonists and antagonists of selective 5-HT receptors have been developed and clinically relevant drugs used or investigated for the therapy of IBD, schizophrenia, depression, migraine, obesity, cancer, and other diseases [148,149]. Antagonists of 5-HT3 receptors are used as antiemetics following chemotherapy [245].

11.2. Targeting the TRP-KYN Pathway

- TDO and IDO1 inhibitors. Several dual (TDO/IDO1) inhibitors have been developed for cancer therapy and have entered clinical trials [222,225,247,248]. High expression of TDO in various forms of human cancer, especially bladder carcinoma, hepatocarcinoma, and melanoma, resulted in the investigation of antitumour properties of specific TDO inhibitors, such as taxifolin [249]. The therapeutic effect of specific IDO1 inhibitors, such as epacadostat and indoximod, appears to be less significant than that of dual inhibitors [248]. More perspective than enzyme inhibition is probably vaccination directed against IDO1-expressing cells [222].

- KYNA and neuroprotective KYN derivatives. The antioxidant and neuroprotective properties of KYNA (Section 7.2.3) indicate that it could be used in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases [104,107,109,110]. Data from rodent studies indicate the benefits of KYNA in disorders associated with metabolic syndrome, including its effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism [104,250]. Unfortunately, the studies examining the therapeutic potential of KYNA in humans are not available. KYNA is present in various kinds of food, and small amounts of KYNA of exogenous origin are present in the digestive system and circulation [250].The examples of KYN derivatives with neuroprotective and immunomodulatory effects include Laquinimod and Tranilast. Laquinimod (quinoline-3-carboxamide), probably via AHR activation in astrocytes, down-regulates migration of leukocytes, reduces inflammation and neuroaxonal damage, and is used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis [251,252]. Transilat, an anti-allergic agent investigated in a wide range of disorders, is a derivative of ANA [253].

- KYN transaminase inhibitors. The KYN transaminase inhibitors block the conversion of KYN to KYNA and are being investigated in the treatment of schizophrenia [254].

- Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase inhibitors. Inhibitors of kynurenine 3-monooxygenase limit the production of neurotoxic kynurenines and are being investigated for the treatment of spinal cord injury and neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and Alzheimer’s [255].

- Suppression of QA formation. Injections of 4-chloro-3-hydroxyanthranilate, a 3-HANA oxygenase inhibitor blocking the conversion of 3-HANA into QA, significantly improved functional recovery and preserved white matter in adult guinea pigs after spinal cord injury [256].

11.3. Targeting TRP-IND Pathways

- IPA. The beneficial effects of IPA on maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, as well as its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties, suggest its potential use in the therapy of various diseases [115,132,133,168]. In animal and in vitro studies, IPA has been shown to exert cytostatic effects in cancer and to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis, steatohepatitis, and muscle protein breakdown in inflammatory states [135,226,261,262].

- IAA. The cytotoxic properties of IAA oxidation products led to the hypothesis that they could be used in cancer therapy. The anticancer properties of IAA coupled with horseradish peroxidase have been demonstrated under in vitro conditions [121,263]. Administration of IAA prevents bacterial translocation into the portal blood and protects against alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice [4].

- Tryptamine. Due to the ability of tryptamine to activate 5-HT and trace amine-associated receptors, several drugs derived from tryptamine have been developed to treat migraines and neuropsychiatric disorders [264].

- Probiotics. Probiotics are microorganisms that, when administered, bring beneficial health effects to the host. For example, administering Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which produce AHR agonists, mitigates the detrimental effects of certain microbiota on gut barrier integrity and CNS function [6]. Probiotics have been used for the prevention of age-related disorders and the treatment of various diseases, including IBD, neurological disorders, metabolic syndrome, and liver cirrhosis [136,137,138].

- Indole-3-carbinol. It is a naturally occurring indole derivative found in cruciferous vegetables and a known ligand for AHR. Experimental studies have found that it can prevent colitis-associated microbial dysbiosis, repress colonic inflammation, and prevent hepatotoxicity, neuronal damage, and carcinogenesis induced by various chemicals [227,228].

- AST-120. A substance that reduces indole absorption from the gut and indoxyl-sulfate levels in plasma has been investigated in the therapy of CRI [196].

12. Summary and Conclusions

- Clinical research should prioritize longitudinal and interventional studies to establish causal links between TRP intake, microbiota-derived metabolites, and host metabolism and neuroimmune responses.

- Large randomized clinical trials are needed to define long-term efficacy and clinically relevant outcomes of TRP administration and targeting TRP catabolism pathways.

- Rigorous evaluation of the safety and dose–response of TRP supplementation will support the development of personalized nutritional and therapeutic strategies.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, F.; Du, R.; Shang, Y. Biological function of d-tryptophan: A bibliometric analysis and review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1455540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitz, J. The kynurenine pathway: A finger in every pie. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiboub, M.; Verburgt, C.M.; Sovran, B.; Benninga, M.A.; de Jonge, W.J.; Van Limbergen, J.E. Nutritional Therapy to Modulate Tryptophan Metabolism and Aryl Hydrocarbon-Receptor Signaling Activation in Human Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrikx, T.; Schnabl, B. Indoles: Metabolites produced by intestinal bacteria capable of controlling liver disease manifestation. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 286, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Vyavahare, S.; Duchesne Blanes, I.L.; Berger, F.; Isales, C.; Fulzele, S. Microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolism: Impacts on health, aging, and disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 183, 112319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2018, 11, 1178646918802282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmaine, S.; Schnellbaecher, A.; Zimmer, A. Reactivity and degradation products of tryptophan in solution and proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 696–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B.N.; Buttar, H.S. Evaluation of the antioxidant properties of tryptophan and its metabolites in vitro assay. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2016, 13, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafini, I.; Monteleone, I.; Laudisi, F.; Monteleone, G. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signalling in the Control of Gut Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, C.A.; Litzenburger, U.M.; Sahm, F.; Ott, M.; Tritschler, I.; Trump, S.; Schumacher, T.; Jestaedt, L.; Schrenk, D.; Weller, M.; et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2011, 478, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolšak, A.; Gobec, S.; Sova, M. Indoleamine and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenases as important future therapeutic targets. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 221, 107746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Chen, D.; Ye, Z.; Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Jiao, H.; Duan, M.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic significance of tryptophan metabolism and signaling in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavek, P. Pregnane X Receptor (PXR)-Mediated Gene Repression and Cross-Talk of PXR with Other Nuclear Receptors via Coactivator Interactions. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Luo, Y.Y.; Ren, H.W.; Li, C.J.; Xiang, Z.X.; Luan, Z.L. The role of pregnane X receptor (PXR) in substance metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 959902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palego, L.; Betti, L.; Rossi, A.; Giannaccini, G. Tryptophan Biochemistry: Structural, Nutritional, Metabolic, and Medical Aspects in Humans. J. Amino Acids 2016, 2016, 8952520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.A. Biochemistry of tryptophan in health and disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 1983, 6, 101–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, W.; Radke, M.; Wutzke, K.D. The significance of tryptophan in human nutrition. Amino Acids 1995, 9, 91–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Chen, N. Central metabolic pathway modification to improve L-tryptophan production in Escherichia coli. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Basics in Amino Acid Metabolism in Humans in Health and Disease, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier: London, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-0-443-44534-7. [Google Scholar]

- Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2007, 935, 1–265. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, S.; Billeci, N.; Gotcher, M.; Patel, S.; Almon, A.; Morgan, H.; Abukhalaf, D.; Groer, M. Tryptophan as a biomarker of pregnancy-related immune expression and modulation: An integrative review. Front. Reprod. Health 2025, 6, 1453714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Okubo, H.; Sasaki, S.; Arakawa, M. Tryptophan intake is related to a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: Baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 4215–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, S.L.; Aparecida Gomes, D.; da Silva, C.M.; Barros, W.M.A.; Alves, S.M.; Manhães de Castro, R. Tryptophan Metabolism in Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Nutr. Rev. 2026, 84, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijikata, Y.; Hara, K.; Shiozaki, Y.; Murata, K.; Sameshima, Y. Determination of free tryptophan in plasma and its clinical applications. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1984, 22, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, E.; Farina, F.; Silingardi, M.; Casalgrandi, G.; Gaetani, E.; Laureri, C.F. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of total and free tryptophan in serum from control subjects and liver patients. J. Chromatogr. 1986, 380, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walser, M.; Hill, S.B. Free and protein-bound tryptophan in serum of untreated patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1993, 44, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejak, P.; Szyndler, J.; Kołosowska, K.; Turzyńska, D.; Sobolewska, A.; Walkowiak, J.; Płaźnik, A. Valproate disturbs the balance between branched and aromatic amino acids in rats. Neurotox. Res. 2014, 25, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviano, A.; Cangiano, C.; Preziosa, I.; Riggio, O.; Conversano, L.; Cascino, A.; Ariemma, S.; Rossi Fanelli, F. Plasma tryptophan levels and anorexia in liver cirrhosis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1997, 21, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Why Are Branched-Chain Amino Acids Increased in Starvation and Diabetes? Nutrients 2020, 12, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Role of Impaired Glycolysis in Perturbations of Amino Acid Metabolism in Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtman, R.J.; Wurtman, J.J.; Regan, M.M.; McDermott, J.M.; Tsay, R.H.; Breu, J.J. Effects of normal meals rich in carbohydrates or proteins on plasma tryptophan and tyrosine ratios. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holecek, M.; Kandar, R.; Sispera, L.; Kovarik, M. Acute hyperammonemia activates branched-chain amino acid catabolism and decreases their extracellular concentrations: Different sensitivity of red and white muscle. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holeček, M. The role of skeletal muscle in the pathogenesis of altered concentrations of branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) in liver cirrhosis, diabetes, and other diseases. Physiol. Res. 2021, 70, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascino, A.; Cangiano, C.; Fiaccadori, F.; Ghinelli, F.; Merli, M.; Pelosi, G.; Riggio, O.; Rossi Fanelli, F.; Sacchini, D.; Stortoni, M.; et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amino acid patterns in hepatic encephalopathy. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1982, 27, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.D.; Garfield, A.S.; Marston, O.J.; Shaw, J.; Heisler, L.K. Brain serotonin system in the coordination of food intake and body weight. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2010, 97, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distelmaier, F.; Herebian, D.; Atasever, C.; Beck-Woedl, S.; Mayatepek, E.; Strom, T.M.; Haack, T.B. Blue Diaper Syndrome and PCSK1 Mutations. Pediatrics 2018, 141, S501–S505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welle, S.; Nair, K.S. Relationship of resting metabolic rate to body composition and protein turnover. Am. J. Physiol. 1990, 258, E990–E998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, A.A. Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism: Regulatory and Functional Aspects. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2017, 10, 1178646917691938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.F.; Moore, J.B.; Kell, D.B. The Biology and Biochemistry of Kynurenic Acid, a Potential Nutraceutical with Multiple Biological Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenepoel, P.; Claus, D.; Geypens, B.; Hiele, M.; Geboes, K.; Rutgeerts, P.; Ghoos, Y. Amount and fate of egg protein escaping assimilation in the small intestine of humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, G935–G943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, D.K.; Lönnerdal, B.; Fernstrom, J.D. Applications for α-lactalbumin in human nutrition. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeds, P.J.; Fjeld, C.R.; Jahoor, F. Do the differences between the amino acid compositions of acute-phase and muscle proteins have a bearing on nitrogen loss in traumatic states? J. Nutr. 1994, 124, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus, A.J.; Allen, T.W. The role of tryptophan side chains in membrane protein anchoring and hydrophobic mismatch. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itakura, K.; Uchida, K.; Kawakishi, S. Selective formation of oxindole- and formylkynurenine-type products from tryptophan and its peptides treated with a superoxide-generating system in the presence of iron(III)-EDTA: A possible involvement with iron-oxygen complex. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994, 7, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; DiDonato, J.A.; Levison, B.S.; Schmitt, D.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Buffa, J.; Kim, T.; Gerstenecker, G.S.; Gu, X.; et al. An abundant dysfunctional apolipoprotein A1 in human atheroma. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, D.; Murphy, J.M.; Doyle, B.; O’Donnell, A.M.; Gillick, J.; Puri, P. Altered tryptophan hydroxylase 2 expression in enteric serotonergic nerves in Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 4662–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Sugawara, Y.; Sawabe, K.; Ohashi, A.; Tsurui, H.; Xiu, Y.; Ohtsuji, M.; Lin, Q.S.; Nishimura, H.; Hasegawa, H.; et al. Late developmental stage-specific role of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 in brain serotonin levels. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, J.; Hoyer, D. Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav. Brain Res. 2008, 195, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.M.; Namkung, J.; Go, Y.; Shong, K.E.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Park, B.Y.; Lee, H.W.; Jeon, Y.H.; Song, J.; et al. Regulation of systemic energy homeostasis by serotonin in adipose tissues. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, M. Inhibition of serotonin synthesis: A novel therapeutic paradigm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 205, 107423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Sun, E.W.; Martin, A.M.; Keating, D.J. The ever-changing roles of serotonin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 125, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrani, M.; Dall’Olio, E.; De Rensis, F.; Tummaruk, P.; Saleri, R. Bioactive Peptides in Dairy Milk: Highlighting the Role of Melatonin. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, J.C.; Chen, K.; Ridd, M.J. Role of MAO A and B in neurotransmitter metabolism and behavior. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 51, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bortolato, M.; Chen, K.; Shih, J.C. The degradation of serotonin: Role of MAO. In Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin; Müller, C., Jacobs, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, E.E.; Leffler, M.; Rogers, C.; Shaw, M.; Carroll, R.; Earl, J.; Cheung, N.W.; Champion, B.; Hu, H.; Haas, S.A.; et al. New insights into Brunner syndrome and potential for targeted therapy. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braam, W.; Spruyt, K. Reference intervals for 6-sulfatoxymelatonin in urine: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 63, 101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R. Melatonin metabolism in the central nervous system. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2010, 8, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haduch, A.; Bromek, E.; Kuban, W.; Daniel, W.A. The Engagement of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Tryptophan Metabolism. Metabolites 2023, 13, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanet, H.; Capuron, L.; Castanon, N.; Calon, F.; Vancassel, S. Tetrahydrobioterin (BH4) Pathway: From Metabolism to Neuropsychiatry. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 19, 591–609. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelreich, N.; Montioli, R.; Bertoldi, M.; Carducci, C.; Leuzzi, V.; Gemperle, C.; Berner, T.; Hyland, K.; Thöny, B.; Hoffmann, G.F.; et al. Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: Molecular and metabolic basis and therapeutic outlook. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 127, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, S.; Wu, X.; He, W.; Song, M. Serotonin signalling in cancer: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, J.D. Role of precursor availability in control of monoamine biosynthesis in brain. Physiol. Rev. 1983, 63, 484–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadda, F. Tryptophan-Free Diets: A Physiological Tool to Study Brain Serotonin Function. News Physiol. Sci. 2000, 15, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- McGlashon, J.M.; Gorecki, M.C.; Kozlowski, A.E.; Thirnbeck, C.K.; Markan, K.R.; Leslie, K.L.; Kotas, M.E.; Potthoff, M.J.; Richerson, G.B.; Gillum, M.P. Central serotonergic neurons activate and recruit thermogenic brown and beige fat and regulate glucose and lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, C.J.; Morrison, S.F. Endogenous activation of spinal 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors contributes to the thermoregulatory activation of brown adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298, R776–R783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawe, G.M.; Hoffman, J.M. Serotonin signalling in the gastrointestinal tract: Functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, M.M.; Green, A.A.; Page, I.H. Partial purification of the vasoconstrictor in beef serum. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 174, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banskota, S.; Ghia, J.E.; Khan, W.I. Serotonin in the gut: Blessing or a curse. Biochimie 2019, 161, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.L.; Lumsden, A.L.; Martin, A.M.; Schober, G.; Pezos, N.; Thazhath, S.S.; Isaacs, N.J.; Cvijanovic, N.; Sun, E.W.L.; Wu, T.; et al. Augmented capacity for peripheral serotonin release in human obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, N.J.; Keating, D.J. Role of 5-HT in the enteric nervous system and enteroendocrine cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, G.P. 5-HT and the immune system. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2011, 11, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Luo, A.; Wei, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, N. Melatonin: Beyond circadian regulation—Exploring its diverse physiological roles and therapeutic potential. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2025, 82, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecon, E.; Oishi, A.; Jockers, R. Melatonin receptors: Molecular pharmacology and signalling in the context of system bias. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 3263–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minich, D.M.; Henning, M.; Darley, C.; Fahoum, M.; Schuler, C.B.; Frame, J. Is Melatonin the “Next Vitamin D”?: A Review of Emerging Science, Clinical Uses, Safety, and Dietary Supplements. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J.; Manchester, L.C.; Yan, M.T.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardeland, R. Chemical and physical properties and potential mechanisms: Melatonin as a broad spectrum antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antolín, I.; Herrera, F.; Martín, V.; Reiter, R.J. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes: A significant role for melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder-Schmittbuhl, M.P.; Hicks, D.; Ribelayga, C.P.; Tosini, G. Melatonin in the mammalian retina: Synthesis, mechanisms of action and neuroprotection. J. Pineal Res. 2024, 76, e12951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batabyal, D.; Yeh, S.R. Human tryptophan dioxygenase: A comparison to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 15690–15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, H.J.; Jusof, F.F.; Bakmiwewa, S.M.; Hunt, N.H.; Yuasa, H.J. Tryptophan-catabolizing enzymes—Party of three. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Niimi, S.; Nawa, K.; Noda, C.; Ichihara, A.; Takagi, Y.; Anai, M.; Sakaki, Y. Multihormonal regulation of transcription of the tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase gene in primary cultures of adult rat hepatocytes with special reference to the presence of a transcriptional protein mediating the action of glucocorticoids. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaessens, S.; Stroobant, V.; De Plaen, E.; Van den Eynde, B.J. Systemic tryptophan homeostasis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 897929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.S.; Coggan, S.E.; Smythe, G.A. The physiological action of picolinic Acid in the human brain. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2009, 2, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Cai, T.; Tagle, D.A.; Li, J. Structure, expression, and function of kynurenine aminotransferases in human and rodent brains. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidetti, P.; Hoffman, G.E.; Melendez-Ferro, M.; Albuquerque, E.X.; Schwarcz, R. Astrocytic localization of kynurenine aminotransferase II in the rat brain visualized by immunocytochemistry. Glia 2007, 55, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.; Shin, I.; Sosova, I.; Dornevil, K.; Jain, S.; Dewey, D.; Liu, F.; Liu, A. Hypertryptophanemia due to tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 120, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonodi, I.; Stine, O.C.; Sathyasaikumar, K.V.; Roberts, R.C.; Mitchell, B.D.; Hong, L.E.; Kajii, Y.; Thaker, G.K.; Schwarcz, R. Downregulated kynurenine 3-monooxygenase gene expression and enzyme activity in schizophrenia and genetic association with schizophrenia endophenotypes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Lysine: Sources, Metabolism, Physiological Importance, and Use as a Supplement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.M. Update current understanding of neurometabolic disorders related to lysine metabolism. Epilepsy Behav. 2023, 146, 109363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, M.; Ueda, M.; Maruyama, K. Role of Kynurenine and Its Derivatives in the Neuroimmune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Liu, Y. Diverse Physiological Roles of Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites: Updated Implications for Health and Disease. Metabolites 2025, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.; Planchais, J.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Schwarcz, R.; Rapoport, S.I.; Takada, Y.; Smith, Q.R. Blood-brain barrier transport of kynurenines: Implications for brain synthesis and metabolism. J. Neurochem. 1991, 56, 2007–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Exploring the etiological links behind neurodegenerative diseases: Inflammatory cytokines and bioactive kynurenines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiratsuka, C.; Fukuwatari, T.; Sano, M.; Saito, K.; Sasaki, S.; Shibata, K. Supplementing healthy women with up to 5.0 g/d of L-tryptophan has no adverse effects. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitt, M.K.; Harper, A.E.; Henderson, L.M. Niacin-tryptophan relationships for evaluating niacin equivalents. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.L.; Cheng, S.P.; Chen, M.J.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, S.N.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chang, Y.C. Quinolinate Phosphoribosyltransferase Promotes Invasiveness of Breast Cancer Through Myosin Light Chain Phosphorylation. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 621944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, L.; Perozzi, S.; Cimadamore, F.; Orsomando, G.; Raffaelli, N. Tissue expression and biochemical characterization of human 2-amino 3-carboxymuconate 6-semialdehyde decarboxylase, a key enzyme in tryptophan catabolism. FEBS J. 2007, 274, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, S.I.; Nyaruhucha, C.M.; Shibata, K. Characterization and functional expression of the cDNA encoding human brain quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1395, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumento, G.; Rotondo, R.; Tonetti, M.; Damonte, G.; Benatti, U.; Ferrara, G.B. Tryptophan-derived catabolites are responsible for inhibition of T and natural killer cell proliferation induced by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, R.; Merchen, T.D.; Fang, X.; Wang, Y. Protective Role of Kynurenine 3-Monooxygenase in Allograft Rejection and Tubular Injury in Kidney Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 671025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, D.H.; Mellor, A.L. Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase and metabolic control of immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón, R.; Blanco-Ayala, T.; Ugalde-Muñiz, P.; Carrillo-Mora, P.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Silva-Adaya, D.; Maldonado, P.D.; Torres, I.; Pinzón, E.; Ortiz-Islas, E.; et al. On the antioxidant properties of kynurenic acid: Free radical scavenging activity and inhibition of oxidative stress. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011, 33, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stípek, S.; Stastný, F.; Pláteník, J.; Crkovská, J.; Zima, T. The effect of quinolinate on rat brain lipid peroxidation is dependent on iron. Neurochem. Int. 1997, 30, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherin, P.S.; Grilj, J.; Tsentalovich, Y.P.; Vauthey, E. Ultrafast excited-state dynamics of kynurenine, a UV filter of the human eye. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009, 113, 4953–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemin, G.J.; Kerr, S.J.; Smythe, G.A.; Smith, D.G.; Kapoor, V.; Armati, P.J.; Croitoru, J.; Brew, B.J. Kynurenine pathway metabolism in human astrocytes: A paradox for neuronal protection. J. Neurochem. 2001, 78, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, S.; Nishiyama, N.; Saito, H.; Katsuki, H. 3-Hydroxykynurenine, an endogenous oxidative stress generator, causes neuronal cell death with apoptotic features and region selectivity. J. Neurochem. 1998, 70, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, R.; Bruno, J.P.; Muchowski, P.J.; Wu, H.Q. Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: When physiology meets pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmas, C.; Pereira, E.F.; Alkondon, M.; Rassoulpour, A.; Schwarcz, R.; Albuquerque, E.X. The brain metabolite kynurenic acid inhibits alpha7 nicotinic receptor activity and increases non-alpha7 nicotinic receptor expression: Physiopathological implications. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 7463–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimerel, C.; Emery, E.; Summers, D.K.; Keyser, U.; Gribble, F.M.; Reimann, F. Bacterial metabolite indole modulates incretin secretion from intestinal enteroendocrine L cells. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Niwa, T.; Maeda, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ohta, K. Tryptophan and indolic tryptophan metabolites in chronic renal failure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1980, 33, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallée, M.; Dou, L.; Cerini, C.; Poitevin, S.; Brunet, P.; Burtey, S. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor-activating effect of uremic toxins from tryptophan metabolism: A new concept to understand cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease. Toxins 2014, 6, 934–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Nawaz, W. The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Li, D.; Sun, F.; Pan, L.; Wang, A.; Li, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, F.; Yue, H. Indole Propionic Acid Regulates Gut Immunity: Mechanisms of Metabolite-Driven Immunomodulation and Barrier Integrity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2503045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owe-Larsson, M.; Drobek, D.; Iwaniak, P.; Kloc, R.; Urbanska, E.M.; Chwil, M. Microbiota-Derived Tryptophan Metabolite Indole-3-Propionic Acid-Emerging Role in Neuroprotection. Molecules 2025, 30, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.S.; Jung, S.; Hwang, G.S.; Shin, D.M. Gut microbiota indole-3-propionic acid mediates neuroprotective effect of probiotic consumption in healthy elderly: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial and in vitro study. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Sawrey-Kubicek, L.; Beals, E.; Rhodes, C.H.; Houts, H.E.; Sacchi, R.; Zivkovic, A.M. Human gut microbiome composition and tryptophan metabolites were changed differently by fast food and Mediterranean diet in 4 days: A pilot study. Nutr. Res. 2020, 77, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosuge, T.; Heskett, M.G.; Wilson, E.E. Microbial synthesis and degradation of indole-3-acetic acid. I. The conversion of L-tryptophan to indole-3-acetamide by an enzyme system from Pseudomonas savastanoi. J. Biol. Chem. 1966, 241, 3738–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y. New Insights Into Gut-Bacteria-Derived Indole and Its Derivatives in Intestinal and Liver Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 769501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, M.P.; de Lima, T.M.; Pithon-Curi, T.C.; Curi, R. The mechanism of indole acetic acid cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 148, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W.C.; Lambert, G.F.; Coon, M.J. The amino acid requirements of man. VII. General procedures; the tryptophan requirement. J. Biol. Chem. 1954, 211, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessa, G.L.; Biggio, G.; Fadda, F.; Corsini, G.U.; Tagliamonte, A. Tryptophan-free diet: A new means for rapidly decreasing brain tryptophan content and serotonin synthesis. Acta Vitaminol. Enzymol. 1975, 29, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindseth, G.; Helland, B.; Caspers, J. The effects of dietary tryptophan on affective disorders. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 29, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhé, H.G.; Mason, N.S.; Schene, A.H. Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: A meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillmann, M.K.; Van der Does, A.W.; Rankin, M.A.; Vuolo, R.D.; Alpert, J.E.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Hayden, D.; Schoenfeld, D.; Fava, M. Tryptophan depletion in SSRI-recovered depressed outpatients. Psychopharmacology 2001, 155, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopelski, P.; Konop, M.; Gawrys-Kopczynska, M.; Podsadni, P.; Szczepanska, A.; Ufnal, M. Indole-3-Propionic Acid, a Tryptophan-Derived Bacterial Metabolite, Reduces Weight Gain in Rats. Nutrients 2019, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusufu, I.; Ding, K.; Smith, K.; Wankhade, U.D.; Sahay, B.; Patterson, G.T.; Pacholczyk, R.; Adusumilli, S.; Hamrick, M.W.; Hill, W.D.; et al. A Tryptophan-Deficient Diet Induces Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Increases Systemic Inflammation in Aged Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, L.C.; Kaiser, K.A.; de Los Santos-Alexis, K.; Park, H.; Uhlemann, A.C.; Gray, D.H.D.; Arpaia, N. Dietary tryptophan deficiency promotes gut RORγt+ Treg cells at the expense of Gata3+ Treg cells and alters commensal microbiota metabolism. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgdrager, F.J.H.; Vermeiren, Y.; Van Faassen, M.; van der Ley, C.; Nollen, E.A.A.; Kema, I.P.; De Deyn, P.P. Age- and disease-specific changes of the kynurenine pathway in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2019, 151, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenkrug, G.; Navrotska, V. Extension of life span by down-regulation of enzymes catalyzing tryptophan conversion into kynurenine: Possible implications for mechanisms of aging. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, C.; Gao, J. Extensive summary of the important roles of indole propionic acid, a gut microbial metabolite in host health and disease. Nutrients 2022, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappolla, M.A.; Perry, G.; Fang, X.; Zagorski, M.; Sambamurti, K.; Poeggeler, B. Indoles as essential mediators in the gut-brain axis. Their role in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 156, 105403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holecek, M. Leucine metabolism in fasted and tumor necrosis factor-treated rats. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 15, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Qi, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z. Indole-3-Propionic Acid, a Functional Metabolite of Clostridium sporogenes, Promotes Muscle Tissue Development and Reduces Muscle Cell Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natividad, J.M.; Agus, A.; Planchais, J.; Lamas, B.; Jarry, A.C.; Martin, R.; Michel, M.L.; Chong-Nguyen, C.; Roussel, R.; Straube, M.; et al. Impaired Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligand Production by the Gut Microbiota Is a Key Factor in Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 737–749.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, A.; Campagna, F.; Amodio, P.; Tuohy, K.M. Gut:liver:brain axis: The microbial challenge in the hepatic encephalopathy. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1373–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.K. Gut microbiota and hepatic encephalopathy. Metab. Brain Dis. 2013, 28, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, A.A. Tryptophan metabolism in alcoholism. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2002, 15, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N. Alcohol and melatonin. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Oretti, R.G.; Morgan, C.J.; Badawy, A.A.; Buckland, P.R.; McGuffin, P. Effects of chronic administration and subsequent withdrawal of ethanol-containing liquid diet on rat liver tryptophan pyrrolase and tryptophan metabolism. Alcohol. Alcohol. 1996, 31, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mechtcheriakov, S.; Gleissenthall, G.V.; Geisler, S.; Arnhard, K.; Oberacher, H.; Schurr, T.; Kemmler, G.; Unterberger, C.; Fuchs, D. Tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism during acute alcohol withdrawal in patients with alcohol use disorder: The role of immune activation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 46, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.; Jolley, S.E.; Molina, P.E. Alcoholic Myopathy: Pathophysiologic Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Alcohol. Res. 2017, 38, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shajib, M.S.; Chauhan, U.; Adeeb, S.; Chetty, Y.; Armstrong, D.; Halder, S.L.S.; Marshall, J.K.; Khan, W.I. Characterization of Serotonin Signaling Components in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2019, 2, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Wang, H.; Terc, J.D.; Zambrowicz, B.; Yang, Q.M.; Khan, W.I. Blocking peripheral serotonin synthesis by telotristat etiprate (LX1032/LX1606) reduces severity of both chemical- and infection-induced intestinal inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 309, G455–G465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikander, A.; Sinha, S.K.; Prasad, K.K.; Rana, S.V. Association of Serotonin Transporter Promoter Polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) with Microscopic Colitis and Ulcerative Colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, M.D.; Mahoney, C.R.; Linden, D.R.; Sampson, J.E.; Chen, J.; Blaszyk, H.; Crowell, M.D.; Sharkey, K.A.; Gershon, M.D.; Mawe, G.M.; et al. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, L.; Francavilla, F.; Leopoldo, M.; Lacivita, E. Allosteric Modulators of Serotonin Receptors: A Medicinal Chemistry Survey. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motavallian, A.; Minaiyan, M.; Rabbani, M.; Mahzouni, P.; Andalib, S. Anti-inflammatory effects of alosetron mediated through 5-HT3 receptors on experimental colitis. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 14, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, S.; Schulte, B.; Al-Massad, N.; Thieme, F.; Schulte, D.M.; Bethge, J.; Rehman, A.; Tran, F.; Aden, K.; Häsler, R.; et al. Increased Tryptophan Metabolism Is Associated with Activity of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Du, P.; Xie, Q.; Wang, N.; Li, H.; Smith, E.E.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Huo, G.; Li, B. Protective effects of tryptophan-catabolizing Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS 1.0386 against dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10736–10747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, R.; Aoki-Yoshida, A.; Suzuki, C.; Takayama, Y. Indole-3-pyruvic acid, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor activator, suppresses experimental colitis in mice. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 3683–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busbee, P.B.; Menzel, L.; Alrafas, H.R.; Dopkins, N.; Becker, W.; Miranda, K.; Tang, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Singh, U.; Nagarkatti, M.; et al. Indole-3-carbinol prevents colitis and associated microbial dysbiosis in an IL-22-dependent manner. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e127551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, J.; Sato, S.; Watanabe, K.; Watanabe, T.; Ardiansyah Hirahara, K.; Aoyama, Y.; Tomita, S.; Aso, H.; Komai, M.; Shirakawa, H. Dietary tryptophan alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis through aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 42, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, N.T.; Zhang, K.; Wigmore, R.M.; Kennedy, A.I.; DaSilva, C.R.; Huang, J.; Ambelil, M.; Villagomez, J.H.; O’Connor, G.J.; Longman, R.S.; et al. Dietary L-Tryptophan consumption determines the number of colonic regulatory T cells and susceptibility to colitis via GPR15. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, S.M.; Saltiel, A.R. Adapting to obesity with adipose tissue inflammation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, R.L.; Senadheera, S.; Markus, I.; Liu, L.; Howitt, L.; Chen, H.; Murphy, T.V.; Sandow, S.L.; Bertrand, P.P. A Western diet increases serotonin availability in rat small intestine. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.M.; Young, R.L.; Leong, L.; Rogers, G.B.; Spencer, N.J.; Jessup, C.F.; Keating, D.J. The Diverse Metabolic Roles of Peripheral Serotonin. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraer, M.; Kilic, F. Serotonin: A different player in hypertension-associated thrombosis. Hypertension 2015, 65, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabut, J.M.; Crane, J.D.; Green, A.E.; Keating, D.J.; Khan, W.I.; Steinberg, G.R. Emerging Roles for Serotonin in Regulating Metabolism: New Implications for an Ancient Molecule. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; He, D.; Zhang, M.; Xue, J.; Zhou, D. Short sleep duration predicts risk of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2014, 18, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Tian, Z.; Han, T.; Sun, C.; Li, Y. Dietary Tryptophan and the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: Total Effect and Mediation Effect of Sleep Duration. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2021, 13, 2141–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arto, C.; Rusu, E.C.; Clavero-Mestres, H.; Barrientos-Riosalido, A.; Bertran, L.; Mahmoudian, R.; Aguilar, C.; Riesco, D.; Chicote, J.U.; Parada, D.; et al. Metabolic profiling of tryptophan pathways: Implications for obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 54, e14279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favennec, M.; Hennart, B.; Caiazzo, R.; Leloire, A.; Yengo, L.; Verbanck, M.; Arredouani, A.; Marre, M.; Pigeyre, M.; Bessede, A.; et al. The kynurenine pathway is activated in human obesity and shifted toward kynurenine monooxygenase activation. Obesity 2015, 23, 2066–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussotto, S.; Delgado, I.; Anesi, A.; Dexpert, S.; Aubert, A.; Beau, C.; Forestier, D.; Ledaguenel, P.; Magne, E.; Mattivi, F.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways Are Altered in Obesity and Are Associated with Systemic Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, M.; Pogson, C.I. The role of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in the hormonal control of tryptophan metabolism in isolated rat liver cells. Effects of glucocorticoids and experimental diabetes. Biochem. J. 1985, 229, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallmann, N.H.; Lima, E.S.; Lalwani, P. Dysregulation of Tryptophan Catabolism in Metabolic Syndrome. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2018, 16, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, B.; Pan, T.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Tian, F.; Lu, W.; Chen, W. The therapeutic potential of dietary intervention: Based on the mechanism of a tryptophan derivative-indole propionic acid on metabolic disorders. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 1729–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenkrug, G. Serotonin-kynurenine hypothesis of depressio: Historical overview and recent developments. Curr. Drug Targets 2013, 14, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Chen, Y.; Ju, Y.; Ma, M.; Qin, Y.; Bi, Y.; Liao, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder under different disease states: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, P.L.; Wang, E.W.; Lewis, M.M.; Krzyzanowski, S.; Capan, C.D.; Burmeister, A.R.; Du, G.; Escobar Galvis, M.L.; Brundin, P.; Huang, X.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolites Are Associated with Symptoms and Nigral Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, P.; Luthi-Carter, R.E.; Augood, S.J.; Schwarcz, R. Neostriatal and cortical quinolinate levels are increased in early grade Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 17, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Vakili, K.; Yaghoobpoor, S.; Tavasol, A.; Jazi, K.; Mohamadkhani, A.; Klegeris, A.; McElhinney, A.; Mafi, Z.; Hajiesmaeili, M.; et al. Dynamic changes in kynurenine pathway metabolites in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1013784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. The kynurenine pathway in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanistic and therapeutic considerations. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 323, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.K.; Bilgin, A.; Lovejoy, D.B.; Tan, V.; Bustamante, S.; Taylor, B.V.; Bessede, A.; Brew, B.J.; Guillemin, G.J. Kynurenine pathway metabolomics predicts and provides mechanistic insight into multiple sclerosis progression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarcz, R.; Stone, T.W. The kynurenine pathway and the brain: Challenges, controversies and promises. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderholm, K.R.; Skogh, E.; Olsson, S.K.; Dahl, M.L.; Holtze, M.; Engberg, G.; Samuelsson, M.; Erhardt, S. Increased levels of kynurenine and kynurenic acid in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, S.; Blennow, K.; Nordin, C.; Skogh, E.; Lindström, L.H.; Engberg, G. Kynurenic acid levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with schizophrenia. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 313, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, R.; Rassoulpour, A.; Wu, H.Q.; Medoff, D.; Tamminga, C.A.; Roberts, R.C. Increased cortical kynurenate content in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 50, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javitt, D.C. Glutamate and schizophrenia: Phencyclidine, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2007, 78, 69–108. [Google Scholar]