The Relationship Between Accessibility to Food Destinations and Places for Physical Activity and Children’s BMI: A Sex-Stratified Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

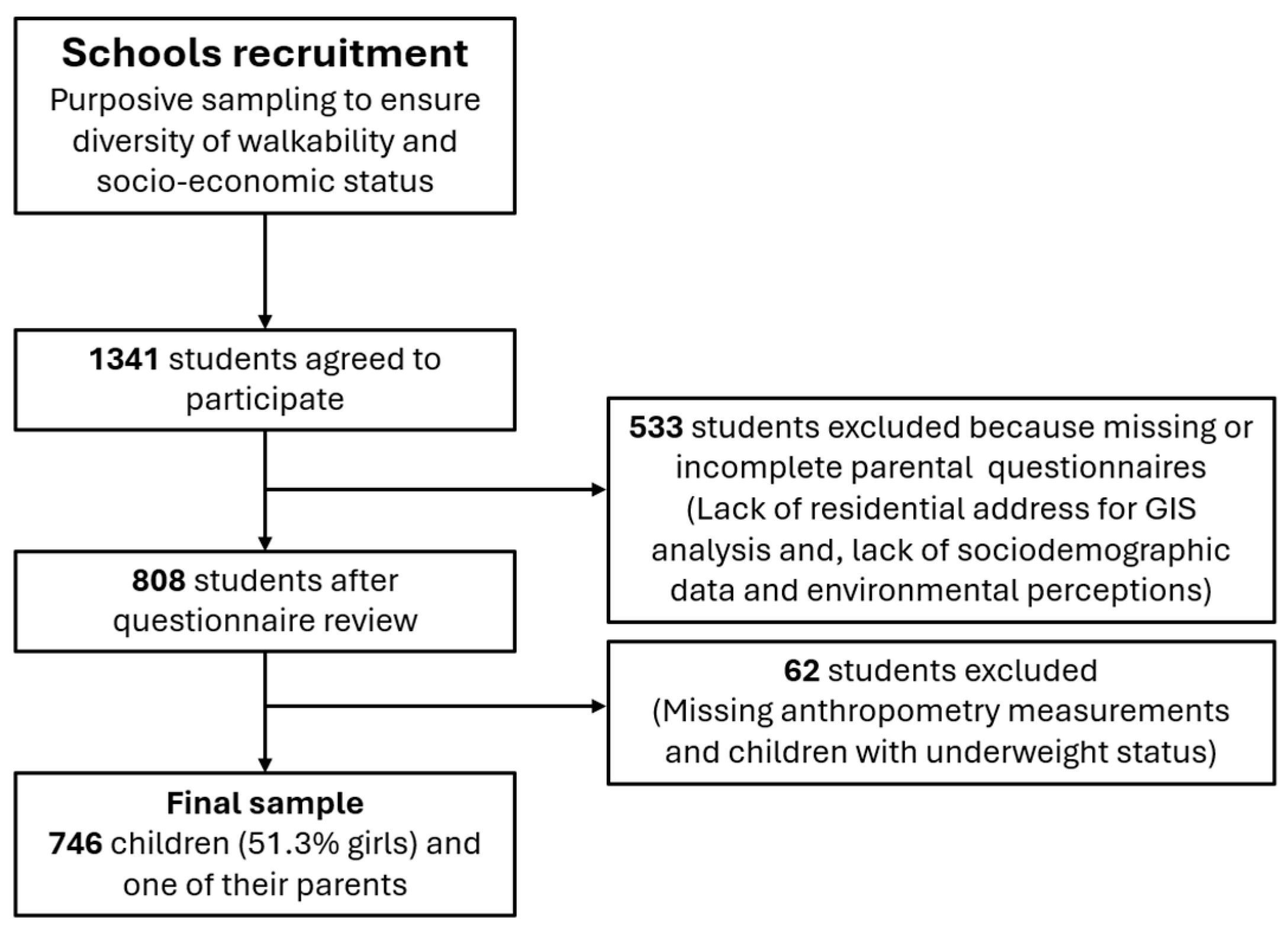

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

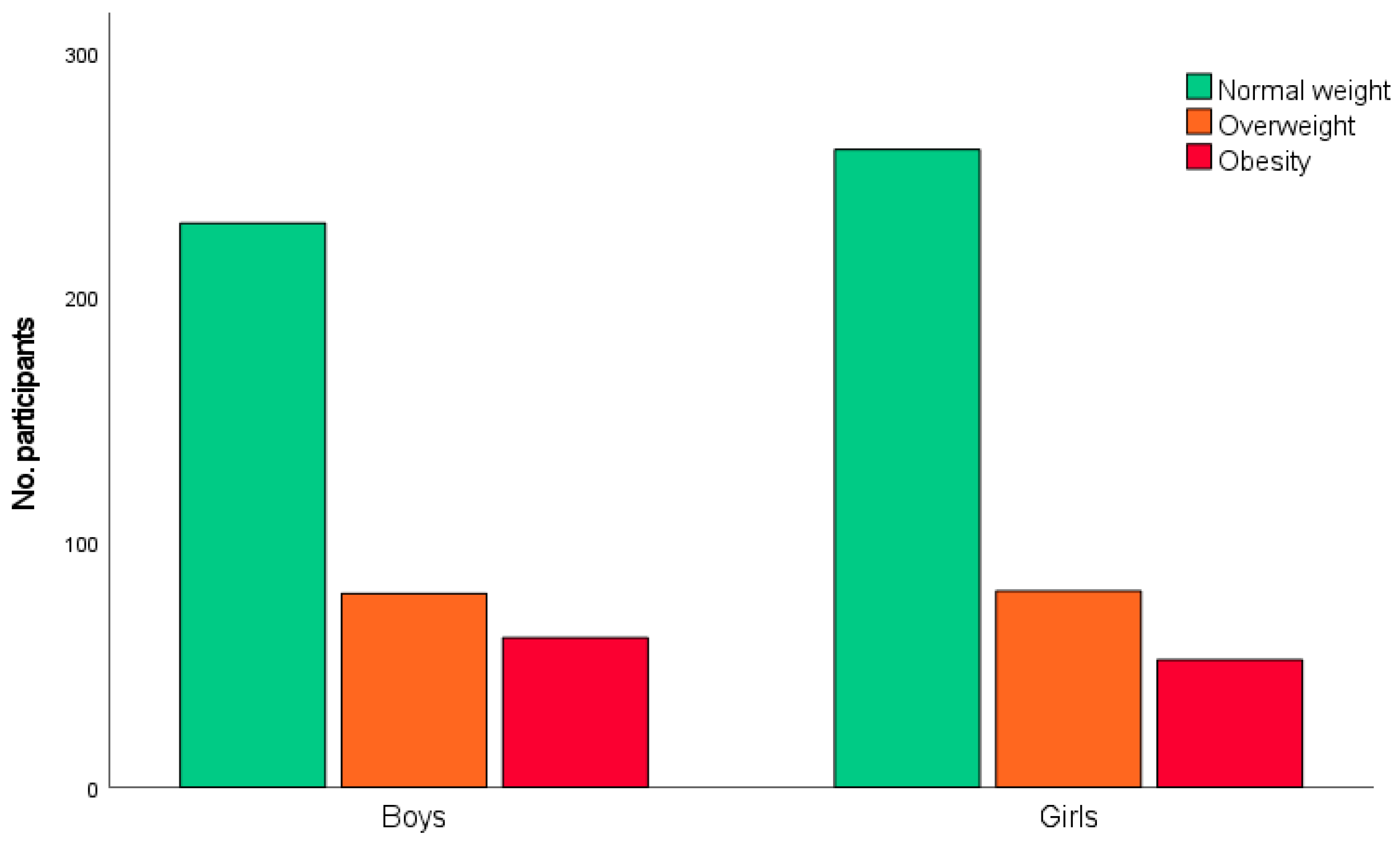

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEACH | Built Environment and Active Children |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| GHSCI | Global Healthy and Sustainable City Indicators |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IPEN | International Physical Activity and the Environment Network |

| NEWS-Y-IPEN | Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale for Youth—IPEN |

| OMS | OpenStreetMap |

| PAQ-C | Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SES | Socio-economic status |

References

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting Adult Obesity from Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Fu, E.; Kobayashi, M.A. Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity and Its Psychological and Health Comorbidities. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 16, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Ni, Y.; Yi, C.; Fang, Y.; Ning, Q.; Shen, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. Global Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertomeu-Gonzalez, V.; Sanchez-Ferrer, F.; Quesada, J.A.; Nso-Roca, A.P.; Lopez-Pineda, A.; Ruiz-Nodar, J.M. Prevalence of Childhood Obesity in Spain and Its Relation with Socioeconomic Status and Health Behaviors: Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Med. Clin. 2024, 163, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C. Neighborhood Playgrounds, Fast Food Restaurants, and Crime: Relationships to Overweight in Low-Income Preschool Children. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.M.; Dooley, E.E.; Ganzar, L.A.; Jovanovic, C.E.; Janda, K.M.; Salvo, D. Neighborhood Food Environment and Physical Activity Among US Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Mavoa, S.; Ikeda, E.; Hasanzadeh, K.; Zhao, J.; Rinne, T.E.; Donnellan, N.; Kyttä, M.; Cui, J. Associations Between Children’s Physical Activity and Neighborhood Environments Using GIS: A Secondary Analysis from a Systematic Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.; Takagi, D.; Hashimoto, H. Association Between Snack Intake Behaviors of Children and Neighboring Women: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Analysis with Spatial Regionalization. SSM-Popul. Health 2024, 28, 101720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F.; Jones, A.P.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Cassidy, A.; Bentham, G.; Griffin, S.J. Environmental Correlates of Adiposity in 9–10 Year Old Children: Considering Home and School Neighbourhoods and Routes to School. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Wang, Y. Changes in the Neighborhood Food Store Environment and Children’s Body Mass Index at Peripuberty in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Gebel, K. Built Environment, Physical Activity, and Obesity: What Have We Learned from Reviewing the Literature? Health Place 2012, 18, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.; Floyd, M.; Rodríguez, D.; Saelens, B. Role of Built Environments in Physical Activity, Obesity, and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-García, J.; Menescardi, C.; Estevan, I.; Queralt, A. Associations Between Park and Playground Availability and Proximity and Children’s Physical Activity and Body Mass Index: The BEACH Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Lu, X.; Xiao, T. The Influence of Neighborhood Built Environment on School-Age Children’s Outdoor Leisure Activities and Obesity: A Case Study of Shanghai Central City in China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1168077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, R.M.; Telford, R.D.; Olive, L.S.; Cochrane, T.; Davey, R. Why Are Girls Less Physically Active than Boys? Findings from the LOOK Longitudinal Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadpoor, M.; Soltani, A.; Fatehnia, L.; Soltani, N. How the Built Environment Moderates Gender Gap in Active Commuting to Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fults, K.K.; Fransen, K.; Boussauw, K. An Exploration into the Levels of Automobile Usage and Independent Mobility for Children in Belgium. Child. Geogr. 2025, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-García, J.; Queralt, A.; Adams, M.A.; Conway, T.L.; Sallis, J.F. Neighborhood Built Environment and Socio-Economic Status in Relation to Multiple Health Outcomes in Adolescents. Prev. Med. 2017, 105, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, O.K.; Gebremariam, M.K.; Kolle, E.; Tarp, J. Socioeconomic Position, Built Environment and Physical Activity Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Mediating and Moderating Effects. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, S.; Santos, R.; Moreira, C.; Santos, P.C.; Mota, J.; Moreira, P. Food Consumption, Physical Activity and Socio-Economic Status Related to BMI, Waist Circumference and Waist-to-Height Ratio in Adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1834–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lim, H. The Global Childhood Obesity Epidemic and the Association Between Socio-Economic Status and Childhood Obesity. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2012, 24, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-García, J.; García-Massó, X.; Menescardi, C.; Estevan, I.; Queralt, A. Parental Neighbourhood Perceptions and Active Commuting to School in Children According to Their Sex Using a Self-Organised Map Approach: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, K.L.; Salmon, J.; Conway, T.L.; Cerin, E.; Hinckson, E.; Mitáš, J.; Schipperijn, J.; Frank, L.D.; Anjana, R.M.; Barnett, A. International Physical Activity and Built Environment Study of Adolescents: IPEN Adolescent Design, Protocol and Measures. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development; Vital and health statistics. Series 11, Data from the National Health Survey; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 1–190.

- Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Barnett, A.; Smith, M.; Veitch, J.; Cain, K.L.; Salonna, F.; Reis, R.S.; Molina-García, J.; Hinckson, E.; et al. Development and Validation of the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale for Youth Across Six Continents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, J.C.; Cutumisu, N.; Edwards, J.; Raine, K.D.; Smoyer-Tomic, K. Relation Between Local Food Environments and Obesity among Adults. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, J.P.; Christakis, N.A.; O’Malley, A.J.; Subramanian, S. Proximity to Food Establishments and Body Mass Index in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort over 30 Years. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G.; Higgs, C.; Liu, S.; Giles-Corti, B.; Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Lowe, M.; Adlakha, D.; Hinckson, E.; Moudon, A.V. Using Open Data and Open-Source Software to Develop Spatial Indicators of Urban Design and Transport Features for Achieving Healthy and Sustainable Cities. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e907–e918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, C.; Liu, S.; Boeing, G.; Arundel, J.; Lowe, M.; Adlakha, D.; Resendiz, E.; Heikinheimo, V.; Gilles-Corti, B.; Delclòs-Alió, X.; et al. Global Healthy and Sustainable City Indicators Software. Global Observatory of Healthy and Sustainable Cities. Available online: https://healthysustainablecities.github.io/software/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Atlas de Distribución de Renta de Los Hogares. Metodología y Resultados. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177088&menu=metodologia&idp=1254735976608 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Manchola-González, J.; Bagur-Calafat, C.; Girabent-Farrés, M. Reliability Spanish Version of Questionnaire of Physical Activity PAQ-C. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fis. Dep. 2017, 17, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Porres, J.; López-Fernández, I.; Raya, J.F.; Álvarez Carnero, S.; Alvero-Cruz, J.R.; Álvarez Carnero, E. Reliability and Validity of the PAQ-C Questionnaire to Assess Physical Activity in Children. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schielzeth, H.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Westneat, D.F.; Allegue, H.; Teplitsky, C.; Réale, D.; Dochtermann, N.A.; Garamszegi, L.Z.; Araya-Ajoy, Y.G. Robustness of Linear Mixed-Effects Models to Violations of Distributional Assumptions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.M.; Schinasi, L.H.; Auchincloss, A.H.; Forrest, C.B.; Roux, A.V.D. The Built and Social Neighborhood Environment and Child Obesity: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdumijit, T.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, R. Neighborhood Food Environment and Children’s BMI: A New Framework with Structural Equation Modeling. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacarne, D.; Handakas, E.; Robinson, O.; Pineda, E.; Saez, M.; Chatzi, L.; Fecht, D. The Built Environment as Determinant of Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Forseth, B.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Laroche, H.H.; Hampl, S.; Davis, A.M.; Steel, C.; Carlson, J. Prospective Associations of Neighborhood Healthy Food Access and Walkability with Weight Status in a Regional Pediatric Health System. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. Food Environments and Obesity—Neighbourhood or Nation? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.A.; Koster, A.; Eussen, S.J.; Pinho, M.G.M.; Lakerveld, J.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Dagnelie, P.C.; van der Kallen, C.J.; van Greevenbroek, M.M.J.; Wesselius, A.; et al. The Association Between the Food Environment and Adherence to Healthy Diet Quality: The Maastricht Study. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, L.F.; Ritchie, L.D.; Gosliner, W.; Plank, K.R.; Au, L.E. Perceived Produce Availability and Child Fruit and Vegetable Intake: The Healthy Communities Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloveva, M.V.; Barnett, A.; Mellecker, R.; Sit, C.; Lai, P.; Zhang, C.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E. Neighbourhood, School and Home Food Environment Associations with Dietary Behaviours in Hong Kong Adolescents: The iHealth Study. Health Place 2025, 93, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Boys (n = 363) | Girls (n = 383) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t-student | p | |

| Convenience store | 4.49 | 0.88 | 4.53 | 0.81 | −0.59 | 0.279 |

| Supermarket | 4.42 | 0.84 | 4.36 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.174 |

| Healthy restaurant proximity index | 0.54 | 1.36 | 0.40 | 1.29 | 1.40 | 0.081 |

| Coffee place | 4.54 | 0.85 | 4.55 | 0.87 | −0.24 | 0.405 |

| Fresh food market | 90.41 | 26.05 | 93.44 | 21.13 | −1.72 | 0.043 |

| Sports and recreational facilities | 3.79 | 1.08 | 3.71 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 0.145 |

| Public park | 4.27 | 0.81 | 4.30 | 0.77 | −0.60 | 0.274 |

| Neighborhood income | 12,711.36 | 3418.72 | 12,921.55 | 3569.09 | −0.77 | 0.220 |

| Neighborhood walkability | 1.94 | 1.53 | 2.11 | 1.44 | −1.48 | 0.070 |

| Neighborhood aesthetics | 2.53 | 0.81 | 2.59 | 0.79 | −0.96 | 0.169 |

| Neighborhood safety from crime | 2.75 | 1.03 | 2.59 | 1.00 | 2.02 | 0.022 |

| Physical activity | 3.43 | 0.74 | 3.14 | 0.77 | 4.43 | <0.001 |

| BMI percentile (age and sex-adjusted) | 67.58 | 27.86 | 65.22 | 27.91 | 1.15 | 0.124 |

| Predictor | β | SE | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Boys | 8.16 | 2.77 | 2.95 | 0.003 | 2.72/13.59 |

| Girls | ref. | ||||

| Convenience store | −1.19 | 2.18 | −0.54 | 0.586 | −5.46/3.09 |

| Supermarket | −0.43 | 2.07 | −0.21 | 0.835 | −4.50/3.64 |

| Healthy restaurant proximity index | −0.52 | 1.02 | −0.51 | 0.612 | −2.53/1.49 |

| Coffee place | 0.52 | 2.03 | 0.26 | 0.798 | −3.46/4.50 |

| Fresh food market | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.718 | −0.13/0.19 |

| Sports and recreational facilities | −1.48 | 1.40 | −1.06 | 0.290 | −4.24/1.27 |

| Public park | 0.44 | 1.97 | 0.22 | 0.823 | −3.44/4.32 |

| Neighborhood income | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.00 | 0.318 | −0.00/0.00 |

| Neighborhood walkability | −0.92 | 1.38 | −0.67 | 0.506 | −3.63/1.79 |

| Neighborhood aesthetics | 1.41 | 1.79 | 0.79 | 0.430 | −2.10/4.92 |

| Neighborhood safety from crime | −1.12 | 1.39 | −0.81 | 0.420 | −3.85/1.61 |

| Physical activity | −4.04 | 1.84 | −2.20 | 0.028 | −7.65/−0.43 |

| Age | −0.30 | 1.59 | −0.19 | 0.852 | −3.41/2.82 |

| Boys | Girls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β | SE | t | p | 95% CI | β | SE | t | p | 95% CI |

| Convenience store | 0.12 | 2.92 | 0.04 | 0.966 | −5.64/5.89 | −3.34 | 3.22 | −1.03 | 0.302 | −9.69/3.02 |

| Supermarket | −3.93 | 2.98 | −1.32 | 0.190 | −9.81/1.96 | 1.49 | 2.81 | 0.53 | 0.595 | −4.04/7.02 |

| Healthy restaurant proximity index | 2.25 | 1.40 | 1.61 | 0.108 | −0.50/5.01 | −3.20 | 1.50 | −2.13 | 0.035 | −6.16/−0.23 |

| Coffee place | 0.64 | 3.06 | 0.21 | 0.834 | −5.40/6.69 | 1.26 | 2.70 | 0.47 | 0.642 | −4.07/6.59 |

| Fresh food market | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.910 | −0.24/0.27 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.695 | −0.17/0.25 |

| Sports and recreational facilities | −1.08 | 2.10 | −0.52 | 0.606 | −5.23/3.06 | −1.78 | 1.92 | −0.93 | 0.354 | −5.55/2.00 |

| Public park | −0.82 | 2.72 | −0.30 | 0.764 | −6.17/4.54 | 1.41 | 2.84 | 0.50 | 0.619 | −4.18/7.01 |

| Neighborhood income | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.489 | 0.00/0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.98 | 0.049 | −0.00/−0.00 |

| Neighborhood walkability | −0.70 | 1.85 | −0.38 | 0.704 | −4.35/2.94 | −0.78 | 1.95 | −0.40 | 0.689 | −4.61/3.06 |

| Neighborhood aesthetics | 2.04 | 2.47 | 0.82 | 0.411 | −2.83/6.90 | 0.78 | 2.59 | 0.30 | 0.764 | −4.33/5.89 |

| Neighborhood safety from crime | −0.51 | 1.89 | −0.27 | 0.789 | −4.24/3.23 | −1.55 | 2.01 | −0.77 | 0.442 | −5.51/2.42 |

| Physical activity | −2.61 | 2.65 | −0.98 | 0.326 | −7.84/2.62 | −4.42 | 2.52 | −1.75 | 0.081 | −9.38/0.55 |

| Age | −2.36 | 2.29 | −1.03 | 0.304 | −6.88/2.16 | 1.75 | 2.21 | 0.79 | 0.430 | −2.61/6.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Molina-García, J.; Delclòs-Alió, X.; Estevan, I.; Queralt, A. The Relationship Between Accessibility to Food Destinations and Places for Physical Activity and Children’s BMI: A Sex-Stratified Analysis. Nutrients 2026, 18, 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030493

Molina-García J, Delclòs-Alió X, Estevan I, Queralt A. The Relationship Between Accessibility to Food Destinations and Places for Physical Activity and Children’s BMI: A Sex-Stratified Analysis. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030493

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina-García, Javier, Xavier Delclòs-Alió, Isaac Estevan, and Ana Queralt. 2026. "The Relationship Between Accessibility to Food Destinations and Places for Physical Activity and Children’s BMI: A Sex-Stratified Analysis" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030493

APA StyleMolina-García, J., Delclòs-Alió, X., Estevan, I., & Queralt, A. (2026). The Relationship Between Accessibility to Food Destinations and Places for Physical Activity and Children’s BMI: A Sex-Stratified Analysis. Nutrients, 18(3), 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030493