Varietal Differences in Kidney Beans Modulate Gut Microbiota and Inflammation During High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Cooked Kidney Bean Powders and Experimental Diet Formulation

2.2. Study Design

2.3. 16S rRNA Library Prep and Microbiome Gene Sequencing

Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. SCFAs and Branched-Chain Fatty Acids

2.5. Colon and Hippocampus mRNA Expression

2.6. Colon Histomorphometry

2.7. Serum and Adipose Tissue Biomarkers of Metabolic Dysfunction and Inflammation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Consumption of High-Fat Diet Influenced Body Weight and Body Composition but Not Caloric Intake

3.2. Consumption of Bean-Supplemented High-Fat Diets Altered the Cecal Microbiota Composition and Function in Male Mice

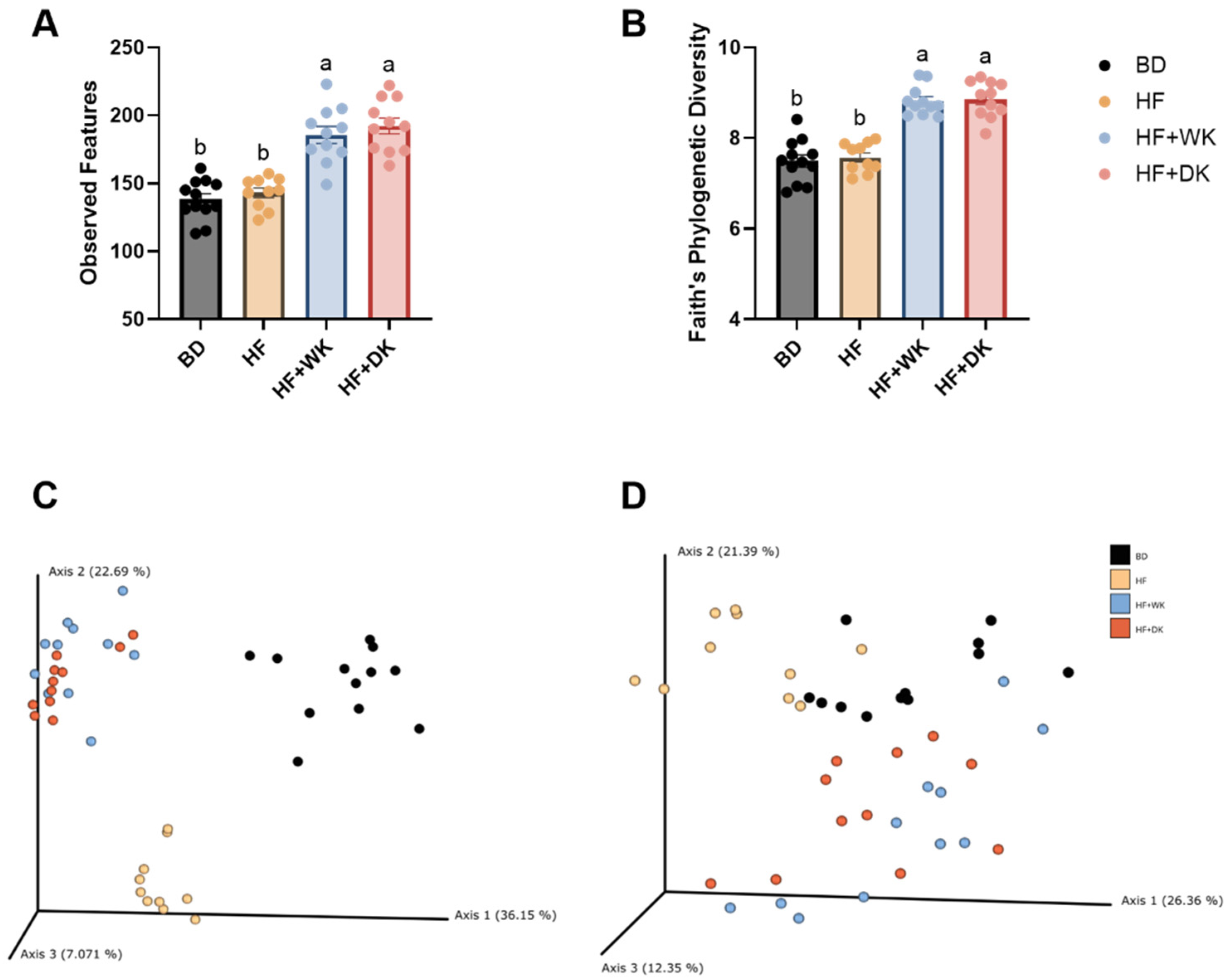

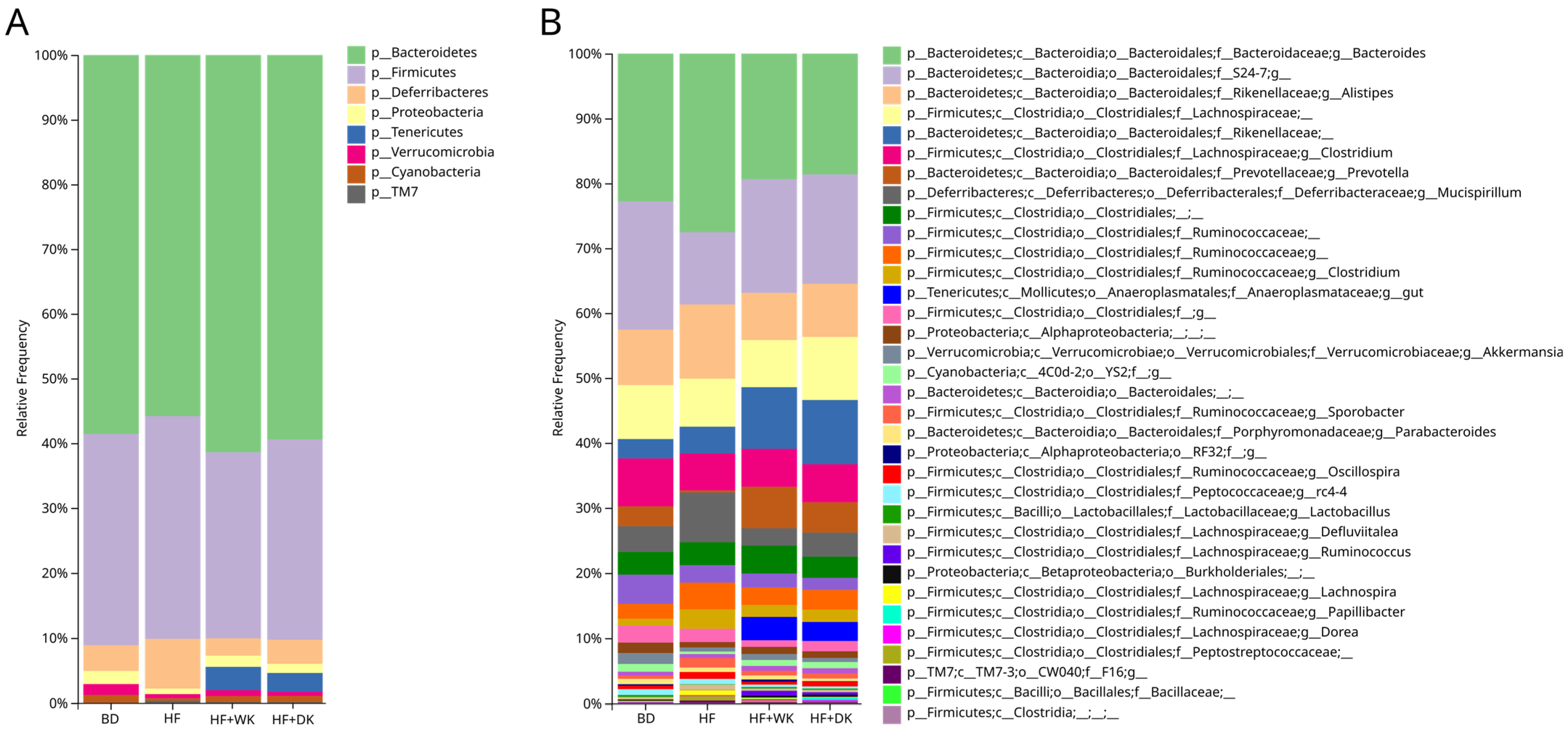

3.2.1. Microbial Community Diversity and Structure

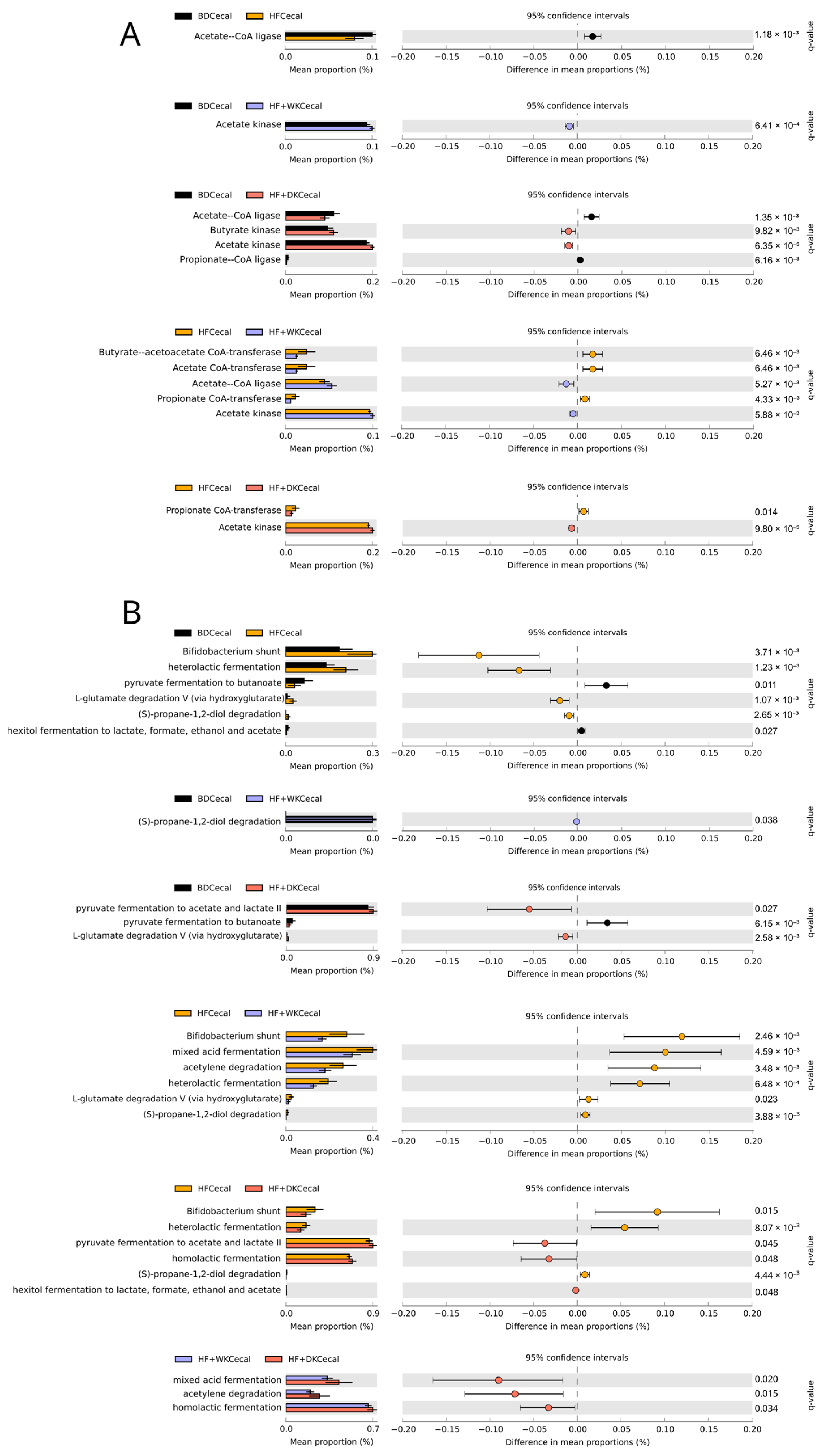

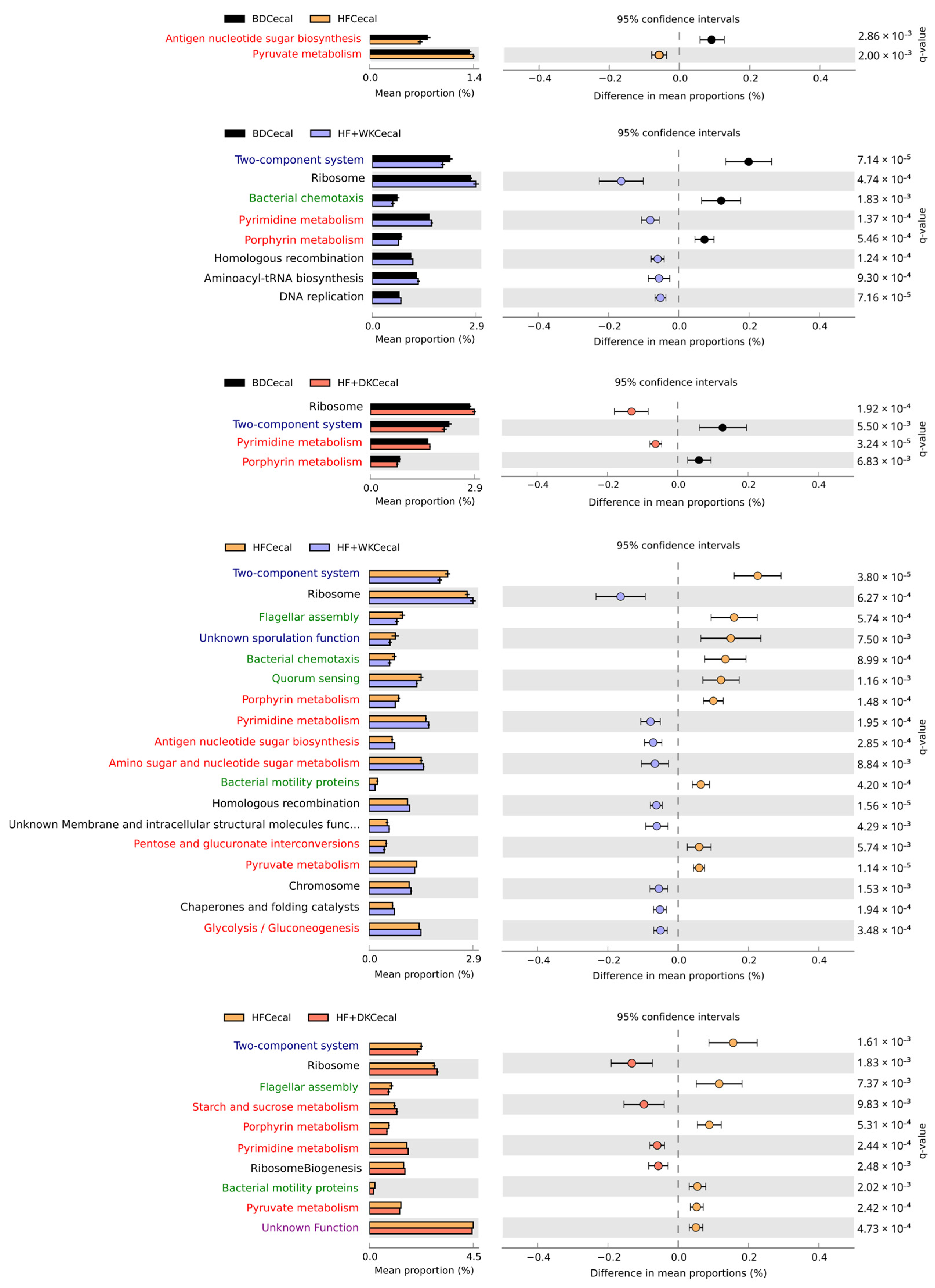

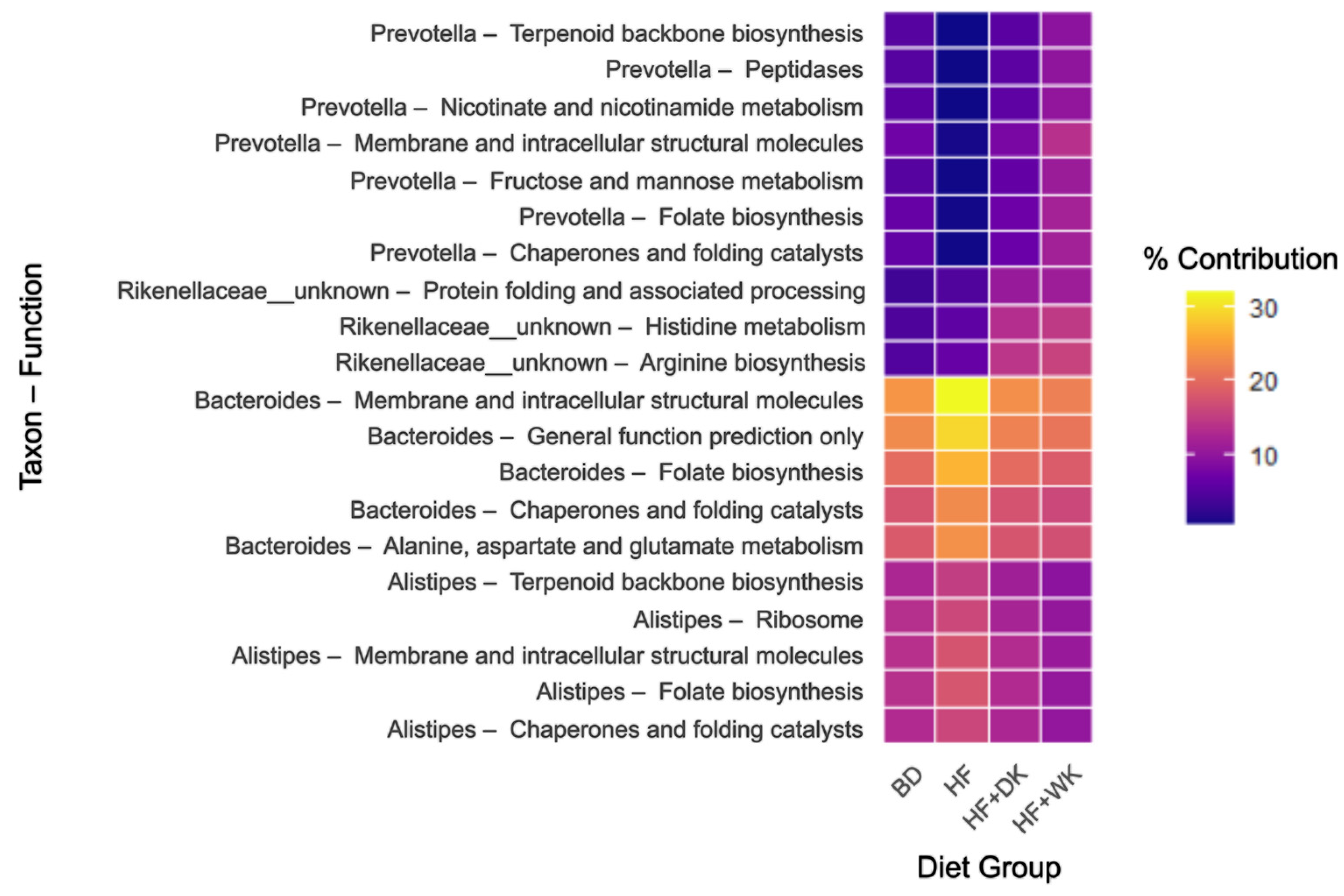

3.2.2. Predicted Function of the Microbiota

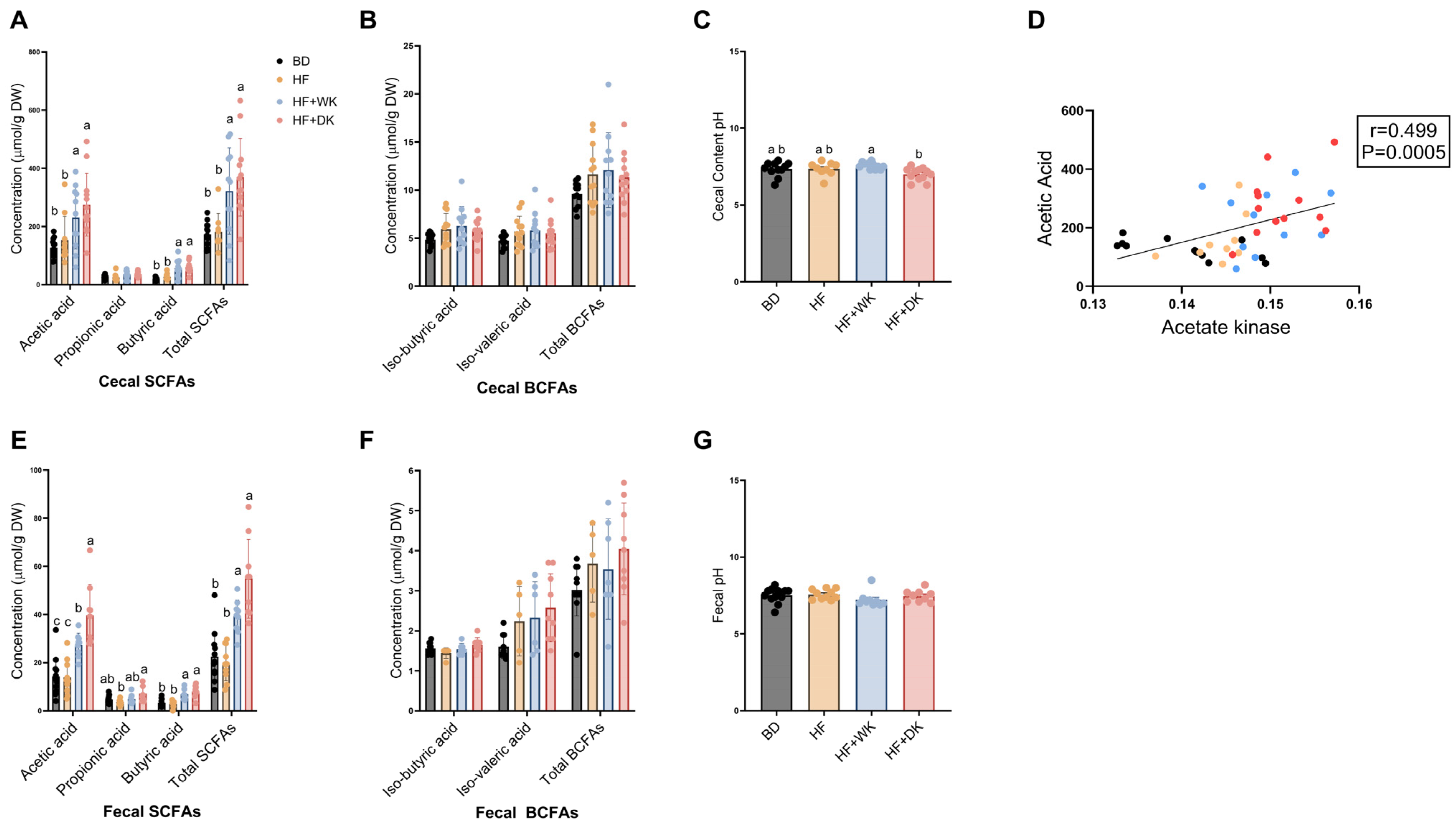

3.2.3. Short-Chain Fatty Acids

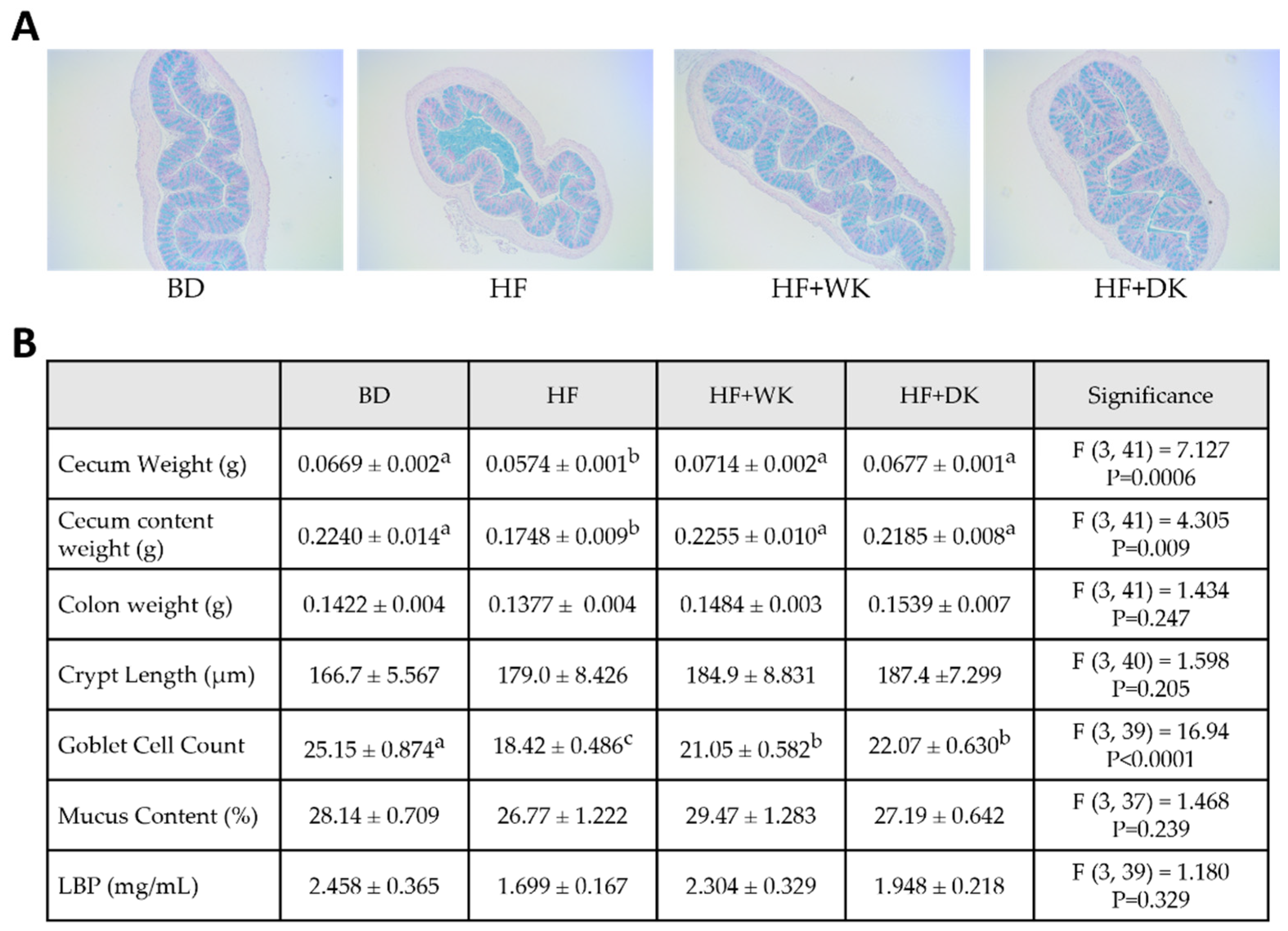

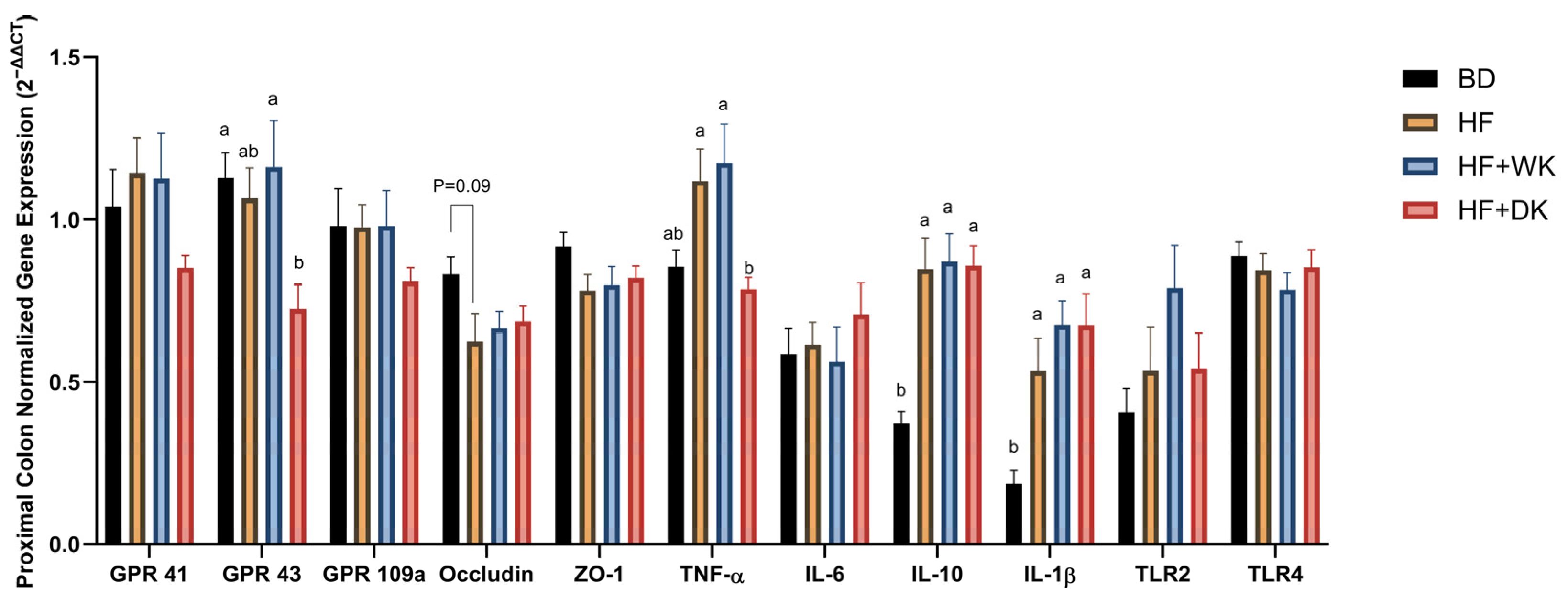

3.3. Consumption of Bean-Supplemented Diets Improved Colon Morphology and Altered Intestinal Inflammation

3.4. Bean Consumption Improved Systemic Inflammation and Metabolic Hormones

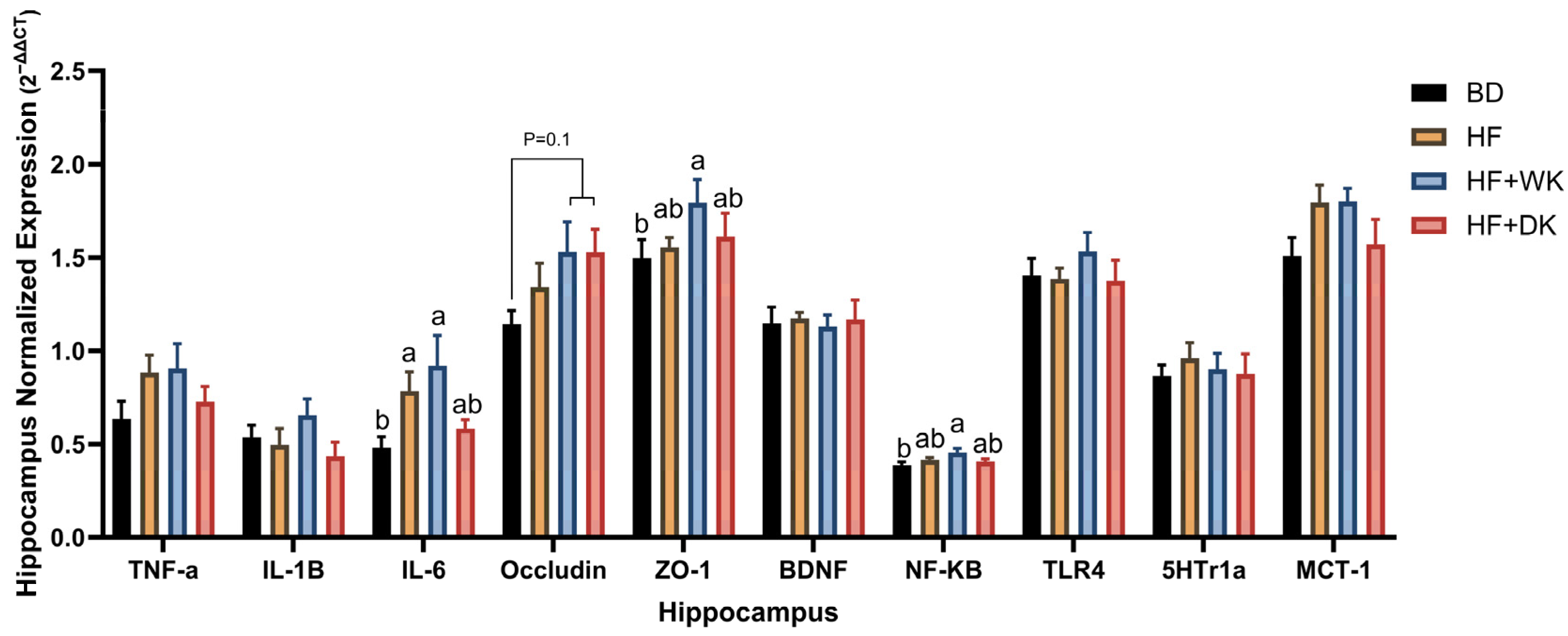

3.5. Bean Consumption Modulated Hippocampal Inflammatory and Blood–Brain Barrier Gene Expression

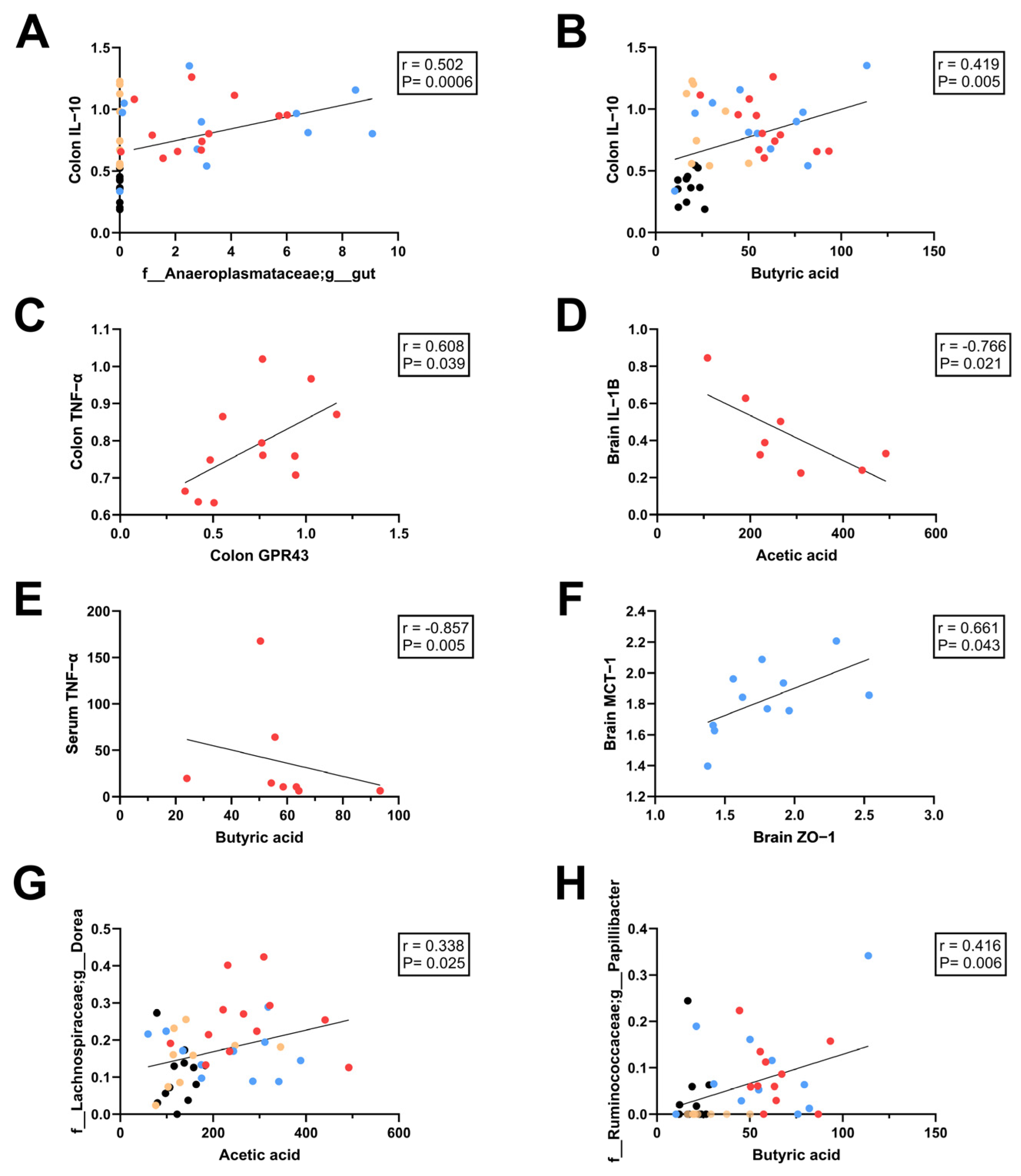

3.6. Relationships Between SCFAs and Intestinal, Systemic, and Neuroinflammation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Blüher, M. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction Contributes to Obesity Related Metabolic Diseases. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 27, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; Den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, N.J.; Bosch-Vermeulen, H.; de Groot, P.J.; Hooiveld, G.J.; Bromhaar, M.M.G.; Jansen, J.; Müller, M.; van der Meer, R. The Role of the Small Intestine in the Development of Dietary Fat-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance in C57BL/6J Mice. BMC Med. Genom. 2008, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.P.; Wang, B.; Jain, S.; Ding, J.; Rejeski, J.; Furdui, C.M.; Kitzman, D.W.; Taraphder, S.; Brechot, C.; Kumar, A.; et al. A Mechanism by Which Gut Microbiota Elevates Permeability and Inflammation in Obese/Diabetic Mice and Human Gut. Gut 2023, 72, 1848–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M.K.; Boudry, G.; Lemay, D.G.; Raybould, H.E. Changes in Intestinal Barrier Function and Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats Are Dynamic and Region Dependent. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 308, G840–G851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.A.; Velazquez, K.T.; Herbert, K.M. Influence of High-Fat Diet on Gut Microbiota: A Driving Force for Chronic Disease Risk. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, F.; Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Tang, J.; Huang, T.; et al. Effects of Dietary Fat on Gut Microbiota and Faecal Metabolites, and Their Relationship with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A 6-Month Randomised Controlled-Feeding Trial. Gut 2019, 68, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Osto, M.; Geurts, L.; Everard, A. Involvement of Gut Microbiota in the Development of Low-Grade Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes Associated with Obesity. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Bibiloni, R.; Knauf, C.; Waget, A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Burcelin, R. Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Metabolic Endotoxemia-Induced Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Diabetes in Mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Possemiers, S.; Van De Wiele, T.; Guiot, Y.; Everard, A.; Rottier, O.; Geurts, L.; Naslain, D.; Neyrinck, A.; Lambert, D.M.; et al. Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Inflammation in Obese Mice through a Mechanism Involving GLP-2-Driven Improvement of Gut Permeability. Gut 2009, 58, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Chi, M.M.; Scull, B.P.; Rigby, R.; Schwerbrock, N.M.J.; Magness, S.; Jobin, C.; Lund, P.K. High-Fat Diet: Bacteria Interactions Promote Intestinal Inflammation Which Precedes and Correlates with Obesity and Insulin Resistance in Mouse. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutoukidis, D.A.; Jebb, S.A.; Zimmerman, M.; Otunla, A.; Henry, J.A.; Ferrey, A.; Schofield, E.; Kinton, J.; Aveyard, P.; Marchesi, J.R. The Association of Weight Loss with Changes in the Gut Microbiota Diversity, Composition, and Intestinal Permeability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2020068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Backhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity Alters Gut Microbial Ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11070–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An Obesity-Associated Gut Microbiome with Increased Capacity for Energy Harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Duncan, S.H.; Scott, K.P.; Louis, P. Links between Diet, Gut Microbiota Composition and Gut Metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Mueller, N.; Álvarez-Quintero, R.; Velásquez-Mejía, E.; Sierra, J.; Corrales-Agudelo, V.; Carmona, J.; Abad, J.; Escobar, J. Higher Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acid Levels Are Associated with Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis, Obesity, Hypertension and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors. Nutrients 2018, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.N.; Yao, Y.; Ju, S.Y. Short Chain Fatty Acids and Fecal Microbiota Abundance in Humans with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwiertz, A.; Taras, D.; Schäfer, K.; Beijer, S.; Bos, N.A.; Donus, C.; Hardt, P.D. Microbiota and SCFA in Lean and Overweight Healthy Subjects. Obesity 2010, 18, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Shen, M.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, J.; Niu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Yao, J.; et al. Elucidating the Specific Mechanisms of the Gut-Brain Axis: The Short-Chain Fatty Acids-Microglia Pathway. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell-Cardona, C.; Leigh, S.-J.; Knox, E.; Tirelli, E.; Lyte, J.M.; Goodson, M.S.; Kelley-Loughnane, N.; Aburto, M.R.; Cryan, J.F.; Clarke, G. Acute Stress-Induced Alterations in Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Implications for the Intestinal and Blood Brain Barriers. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2025, 46, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.A.; Spencer, S.J. Obesity and Neuroinflammation: A Pathway to Cognitive Impairment. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 42, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemot-Legris, O.; Muccioli, G.G. Obesity-Induced Neuroinflammation: Beyond the Hypothalamus. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Oomah, B.D. Minor Components of Pulses and Their Potential Impact on Human Health. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Kumar, G.; Williamson, G.; Devkota, L.; Dhital, S. (Poly)Phenols and Dietary Fiber in Beans: Metabolism and Nutritional Impact in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, Y.; Kaviani, M.; Tosh, S.M. Structural and Functional Characteristics of Dietary Fibre in Beans, Lentils, Peas and Chickpeas. Food Res. Int. 2015, 67, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, A.-Q.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P. Structural Characteristics of Three Pectins Isolated from White Kidney Bean. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T. Formation of Short Chain Fatty Acids by the Gut Microbiota and Their Impact on Human Metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, H.S.; Doucet, É.; Power, K.A. Dietary Pulses as a Means to Improve the Gut Microbiome, Inflammation, and Appetite Control in Obesity. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Johansson, E.; Ekström, L.; Björck, I. Effects of a Brown Beans Evening Meal on Metabolic Risk Markers and Appetite Regulating Hormones at a Subsequent Standardized Breakfast: A Randomized Cross-Over Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Kendall, C.W.C.; de Souza, R.J.; Jayalath, V.H.; Cozma, A.I.; Ha, V.; Mirrahimi, A.; Chiavaroli, L.; Augustin, L.S.A.; Blanco Mejia, S.; et al. Dietary Pulses, Satiety and Food Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Acute Feeding Trials: Dietary Pulse and Food Intake Regulation. Obesity 2014, 22, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reverri, E.J.; Randolph, J.M.; Kappagoda, C.T.; Park, E.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B.M. Assessing Beans as a Source of Intrinsic Fiber on Satiety in Men and Women with Metabolic Syndrome. Appetite 2017, 118, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, A.M.; Winham, D.M.; Thompson, S.V. Phaseolus Beans: Impact on Glycaemic Response and Chronic Disease Risk in Human Subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S52–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.V.; Winham, D.M.; Hutchins, A.M. Bean and Rice Meals Reduce Postprandial Glycemic Response in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-over Study. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, L.A. Bean Consumption Accounts for Differences in Body Fat and Waist Circumference: A Cross-Sectional Study of 246 Women. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 9140907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.L.; Taylor, C.G.; Zahradka, P. Black Beans and Red Kidney Beans Induce Positive Postprandial Vascular Responses in Healthy Adults: A Pilot Randomized Cross-over Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.; McGinley, J.; Neil, E.; Brick, M. Beneficial Effects of Common Bean on Adiposity and Lipid Metabolism. Nutrients 2017, 9, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, S.; Claesen, J. Mechanisms of Gut Bacterial Metabolism of Dietary Polyphenols into Bioactive Compounds. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2426614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, Y.; Estrella, I.; Benitez, V.; Esteban, R.M.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A. Bioactive Phenolic Compounds and Functional Properties of Dehydrated Bean Flours. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.B.; Gutierres, J.M.; Bueno, A.; Agostinho, P.; Zago, A.M.; Vieira, J.; Frühauf, P.; Cechella, J.L.; Nogueira, C.W.; Oliveira, S.M.; et al. Anthocyanins Control Neuroinflammation and Consequent Memory Dysfunction in Mice Exposed to Lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 3350–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Alharbi, A.; Gibson, R.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. (Poly)Phenol-Gut Microbiota Interactions and Their Impact on Human Health. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2025, 28, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M. Multifunctions of Dietary Polyphenols in the Regulation of Intestinal Inflammation. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, J.M.; Zhang, C.P.; Wu, W.; Zarepoor, L.; Lu, J.T.; Liu, R.; Pauls, K.P.; Wood, G.A.; Tsao, R.; Robinson, L.E.; et al. White and Dark Kidney Beans Reduce Colonic Mucosal Damage and Inflammation in Response to Dextran Sodium Sulfate. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombra, M.N.; d’Acierno, A.; Nazzaro, F.; Riccardi, R.; Spigno, P.; Zaccardelli, M.; Pane, C.; Maione, M.; Fratianni, F. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of the Extracts of Twelve Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Endemic Ecotypes of Southern Italy before and after Cooking. Oxidat. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1398298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthria, D.L.; Pastor-Corrales, M.A. Phenolic Acids Content of Fifteen Dry Edible Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Varieties. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsiv, T.; McGinley, J.N.; Neil-McDonald, E.S.; Weir, T.L.; Foster, M.T.; Thompson, H.J. Relandscaping the Gut Microbiota with a Whole Food: Dose–Response Effects to Common Bean. Foods 2022, 11, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Hernández-Velázquez, I.; Pichardo-Ontiveros, E.; Granados-Portillo, O.; Gálvez, A.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N. Consumption of Cooked Black Beans Stimulates a Cluster of Some Clostridia Class Bacteria Decreasing Inflammatory Response and Improving Insulin Sensitivity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Tam, C.C.; Meng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Alves, P.; Yokoyama, W. Cooked Black Turtle Beans Ameliorate Insulin Resistance and Restore Gut Microbiota in C57BL/6J Mice on High-Fat Diets. Foods 2021, 10, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, E.S.; McGinley, J.N.; Fitzgerald, V.K.; Lauck, C.A.; Tabke, J.A.; Streeter-McDonald, M.R.; Yao, L.; Broeckling, C.D.; Weir, T.L.; Foster, M.T.; et al. White Kidney Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Consumption Reduces Fat Accumulation in a Polygenic Mouse Model of Obesity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.M.; Lepp, D.; Zhang, C.P.; Wu, W.; Zarepoor, L.; Lu, J.T.; Pauls, K.P.; Tsao, R.; Wood, G.A.; Robinson, L.E.; et al. Diets Enriched with Cranberry Beans Alter the Microbiota and Mitigate Colitis Severity and Associated Inflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 28, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.M.; Lepp, D.; Wu, W.; Pauls, K.P.; Robinson, L.E.; Power, K.A. Navy and Black Bean Supplementation Primes the Colonic Mucosal Microenvironment to Improve Gut Health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 49, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Rangel, J.C.; Benavides, J.; Heredia, J.B.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. The Folin–Ciocalteu Assay Revisited: Improvement of Its Specificity for Total Phenolic Content Determination. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-Y.; McGregor, R.A.; Kwon, E.-Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, Y.; Park, J.H.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, J.; Yun, J.W.; et al. The Metabolic Response to a High-Fat Diet Reveals Obesity-Prone and -Resistant Phenotypes in Mice with Distinct mRNA-Seq Transcriptome Profiles. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Yu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, R.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Weston-Green, K.; Huang, X.-F.; et al. Alterations to the Microbiota–Colon–Brain Axis in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obese Mice Compared to Diet-Resistant Mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 65, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxinos, G.; Franklin, K.B.J. Paxinos and Franklin’s the Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 5th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, M.B. Cognitive Control of Meal Onset and Meal Size: Role of Dorsal Hippocampal-Dependent Episodic Memory. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 162, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbuin, N.; Sargent-Cox, K.; Fraser, M.; Sachdev, P.; Anstey, K.J. Being Overweight Is Associated with Hippocampal Atrophy: The PATH Through Life Study. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Yau, S. From Obesity to Hippocampal Neurodegeneration: Pathogenesis and Non-Pharmacological Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illumina 16s Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation 2013. Available online: https://support.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-support/documents/documentation/chemistry_documentation/16s/16s-metagenomic-library-prep-guide-15044223-b.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME Allows Analysis of High-Throughput Community Sequencing Data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K. MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.; Price, M.N.; Goodrich, J.; Nawrocki, E.P.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Probst, A.; Andersen, G.L.; Knight, R.; Hugenholtz, P. An Improved Greengenes Taxonomy with Explicit Ranks for Ecological and Evolutionary Analyses of Bacteria and Archaea. ISME J. 2012, 6, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Müller, A.; Nothman, J.; Louppe, G.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Optimizing Taxonomic Classification of Marker-Gene Amplicon Sequences with QIIME 2’s Q2-Feature-Classifier Plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation Evaluation and Phylogenetic Diversity. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.; Knight, R. UniFrac: A New Phylogenetic Method for Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halko, N.; Martinsson, P.-G.; Shkolnisky, Y.; Tygert, M. An Algorithm for the Principal Component Analysis of Large Data Sets. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2011, 33, 2580–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA). In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Balakrishnan, N., Colton, T., Everitt, B., Piegorsch, W., Ruggeri, F., Teugels, J.L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, P.E.; Najab, J. Mann-Whitney U Test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. corpsy0524. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Krieger, A.M.; Yekutieli, D. Adaptive Linear Step-up Procedures That Control the False Discovery Rate. Biometrika 2006, 93, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for Prediction of Metagenome Functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, L.; Stamatakis, A. Scalable Methods for Analyzing and Visualizing Phylogenetic Placement of Metagenomic Samples. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, T.J.; Eddy, S.R. Nhmmer: DNA Homology Search with Profile HMMs. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2487–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirarab, S.; Nguyen, N.; Warnow, T. SEPP: SATé-Enabled Phylogenetic Placement. In Biocomputing 2012; World Scientific: Kohala Coast, HI, USA, 2011; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Louca, S.; Doebeli, M. Efficient Comparative Phylogenetics on Large Trees. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Doak, T.G. A Parsimony Approach to Biological Pathway Reconstruction/Inference for Genomes and Metagenomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Sato, Y.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG for Integration and Interpretation of Large-Scale Molecular Data Sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D109–D114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, M.G.I.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Vega Thurber, R.L.; Knight, R.; et al. Predictive Functional Profiling of Microbial Communities Using 16S rRNA Marker Gene Sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- McNally, C.P.; Eng, A.; Noecker, C.; Gagne-Maynard, W.C.; Borenstein, E. BURRITO: An Interactive Multi-Omic Tool for Visualizing Taxa–Function Relationships in Microbiome Data. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Use R!), 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, M.S.; Suvorova, I.A.; Iablokov, S.N.; Petrov, S.N.; Rodionov, D.A. Genomic Reconstruction of Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production by the Human Gut Microbiota. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 949563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption—Reference Pathway (Map04973). Available online: https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/map04973 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Butanoate Metabolism—Reference Pathway (Map00650). Available online: https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/map00650 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pyruvate Metabolism—Reference Pathway (Map00620). Available online: https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/map00620 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Propanoate Metabolism—Reference Pathway (Map00640). Available online: https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/map00640 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Caspi, R.; Billington, R.; Keseler, I.M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Midford, P.E.; Ong, W.K.; Paley, S.; Subhraveti, P.; Karp, P.D. The MetaCyc Database of Metabolic Pathways and Enzymes—A 2019 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D445–D453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Tyson, G.W.; Hugenholtz, P.; Beiko, R.G. STAMP: Statistical Analysis of Taxonomic and Functional Profiles. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3123–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate Normalization of Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Data by Geometric Averaging of Multiple Internal Control Genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, Y. Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient. In The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 502–505. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Z.; Er, J.Z.; Ding, J.L. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Receptor GPR43 Is Transcriptionally Regulated by XBP1 in Human Monocytes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, J.M.; Wu, W.; Lepp, D.; Pauls, K.P.; Robinson, L.E.; Power, K.A. Navy Bean Supplementation in Established High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity Attenuates the Severity of the Obese Inflammatory Phenotype. Nutrients 2021, 13, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, A.; Stewart, L.; Blanchard, J.; Leschine, S. Untangling the Genetic Basis of Fibrolytic Specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in Diverse Gut Communities. Diversity 2013, 5, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of Propionate and Butyrate by the Human Colonic Microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Permeability, and Systemic Inflammation: A Narrative Review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2023, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bander, Z.; Nitert, M.D.; Mousa, A.; Naderpoor, N. The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Akbar, M.T.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhi, L.; Shen, Q. Exploration of the Muribaculaceae Family in the Gut Microbiota: Diversity, Metabolism, and Function. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herp, S.; Durai Raj, A.C.; Salvado Silva, M.; Woelfel, S.; Stecher, B. The Human Symbiont Mucispirillum schaedleri: Causality in Health and Disease. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 210, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, H.E.; Rodríguez-Piñeiro, A.M.; Schütte, A.; Ermund, A.; Boysen, P.; Bemark, M.; Sommer, F.; Bäckhed, F.; Hansson, G.C.; Johansson, M.E. The Composition of the Gut Microbiota Shapes the Colon Mucus Barrier. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, Y.-C.; Chang, W.-T.; Li, S.; Wu, J.-C.; Badmeav, V.; Ho, C.-T.; Pan, M.-H. Citrus Peel Extracts Attenuated Obesity and Modulated Gut Microbiota in Mice with High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3363–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahe, L.K.; Le Chatelier, E.; Prifti, E.; Pons, N.; Kennedy, S.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Astrup, A.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Larsen, L.H. Specific Gut Microbiota Features and Metabolic Markers in Postmenopausal Women with Obesity. Nutr. Diabetes 2015, 5, e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahnemo, L.; Nethander, M.; Coward, E.; Gabrielsen, M.E.; Sree, S.; Billod, J.-M.; Sjögren, K.; Engstrand, L.; Dekkers, K.F.; Fall, T.; et al. Identification of Three Bacterial Species Associated with Increased Appendicular Lean Mass: The HUNT Study. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceperuelo-Mallafré, V.; Rodríguez-Peña, M.-M.; Badia, J.; Villanueva-Carmona, T.; Cedó, L.; Marsal-Beltran, A.; Benaiges, E.; Núñez-Roa, C.; Salmerón-Pelado, L.; Osuna-Prieto, F.J.; et al. Dietary Switch and Intermittent Fasting Ameliorate the Disrupted Postprandial Short-Chain Fatty Acid Response in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. eBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defnoun, S.; Labat, M.; Ambrosio, M.; Garcia, J.L.; Patel, B.K. Papillibacter cinnamivorans Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Cinnamate-Transforming Bacterium from a Shea Cake Digester. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria with Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, D.; Monk, J.M.; Lepp, D.; Wu, W.; McGillis, L.; Roberton, K.; Brummer, Y.; Tosh, S.M.; Power, K.A. Cooked Red Lentils Dose-Dependently Modulate the Colonic Microenvironment in Healthy C57Bl/6 Male Mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.M.; Lepp, D.; Wu, W.; Graf, D.; McGillis, L.H.; Hussain, A.; Carey, C.; Robinson, L.E.; Liu, R.; Tsao, R.; et al. Chickpea-Supplemented Diet Alters the Gut Microbiome and Enhances Gut Barrier Integrity in C57Bl/6 Male Mice. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 38, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.V.; Hao, L.; Offermanns, S.; Medzhitov, R. The Microbial Metabolite Butyrate Regulates Intestinal Macrophage Function via Histone Deacetylase Inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, A.E.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Raposo, A.; Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmed, F.; Otayf, A.Y.; Carrascosa, C.; Saraiva, A.; Karav, S. Beyond the Gut: Unveiling Butyrate’s Global Health Impact Through Gut Health and Dysbiosis-Related Conditions: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Mu, K.; Arntfield, S.D.; Nickerson, M.T. Changes in Levels of Enzyme Inhibitors during Soaking and Cooking for Pulses Available in Canada. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hefni, M.E.; Witthöft, C.M.; Bergström, M.; Burleigh, S.; Nyman, M.; Hållenius, F. Effects of Whole Brown Bean and Its Isolated Fiber Fraction on Plasma Lipid Profile, Atherosclerosis, Gut Microbiota, and Microbiota-Dependent Metabolites in Apoe−/− Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, J.M.; Wu, W.; Lepp, D.; Wellings, H.R.; Hutchinson, A.L.; Liddle, D.M.; Graf, D.; Pauls, K.P.; Robinson, L.E.; Power, K.A. Navy Bean Supplemented High-Fat Diet Improves Intestinal Health, Epithelial Barrier Integrity and Critical Aspects of the Obese Inflammatory Phenotype. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 70, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Hou, D.; Fu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Guan, X.; Shen, Q. Adzuki Bean Alleviates Obesity and Insulin Resistance Induced by a High-Fat Diet and Modulates Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Dong, L.; Hou, D.; Zhou, S. Protective Effects of White Kidney Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) against Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis in Mice Are Linked to Modification of Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, W.; Chen, L.; Huang, T.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, L.; Feng, K.; Cai, Y.; Wang, H. Computationally Identifying Virulence Factors Based on KEGG Pathways. Mol. BioSyst. 2013, 9, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De La Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.R.; Tomas, J.; Brenner, C.; Sansonetti, P.J. Impact of High-Fat Diet on the Intestinal Microbiota and Small Intestinal Physiology before and after the Onset of Obesity. Biochimie 2017, 141, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyowati, E.; Handayani, D.; Soeharto, S.; Rudijanto, A. A High-Fat and High-Fructose Diet Lowers the Cecal Digesta’s Weight and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Level of a Sprague-Dawley Rat Model. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 52, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, G.; Barbaro, M.R.; Fuschi, D.; Palombo, M.; Falangone, F.; Cremon, C.; Marasco, G.; Stanghellini, V. Inflammatory and Microbiota-Related Regulation of the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 718356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Dietary Fiber and SCFAs in the Regulation of Mucosal Immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Z.; Ding, J.L. GPR41 and GPR43 in Obesity and Inflammation—Protective or Causative? Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornall, L.M.; Mathai, M.L.; Hryciw, D.H.; McAinch, A.J. The Therapeutic Potential of GPR43: A Novel Role in Modulating Metabolic Health. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 4759–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewulf, E.M.; Ge, Q.; Bindels, L.B.; Sohet, F.M.; Cani, P.D.; Brichard, S.M.; Delzenne, N.M. Evaluation of the Relationship between GPR43 and Adiposity in Human. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Chang, X.; Qi, K. Short Chain Fatty Acids Prevent High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice by Regulating G Protein-Coupled Receptors and Gut Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, W.K.E.; Hoshi, N.; Shouval, D.S.; Snapper, S.; Medzhitov, R. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of IL-10 Mediated by Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages. Science 2017, 356, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in Obesity, Diabetes, and Related Disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tsao, R. Dietary Polyphenols, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Du, B.; Xu, B. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Phytochemicals from Fruits, Vegetables, and Food Legumes: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.; Kiefer, F.W.; Zeyda, M.; Ludvik, B.; Silberhumer, G.R.; Prager, G.; Zlabinger, G.J.; Stulnig, T.M. CC Chemokine and CC Chemokine Receptor Profiles in Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Are Altered in Human Obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 3215–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, R.; Karastergiou, K.; Ogston, N.C.; Miheisi, N.; Bhome, R.; Haloob, N.; Tan, G.D.; Karpe, F.; Malone-Lee, J.; Hashemi, M.; et al. RANTES Release by Human Adipose Tissue In Vivo and Evidence for Depot-Specific Differences. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 296, E1262–E1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-Y.; Ajoy, R.; Changou, C.A.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Wang, Y.-K.; Hoffer, B. CCL5/RANTES Contributes to Hypothalamic Insulin Signaling for Systemic Insulin Responsiveness through CCR5. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liao, X.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Hu, W.; Sun, X.; Ding, Y.; Wang, D.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Metabolic Effects of CCL5 Deficiency in Lean and Obese Mice. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1059687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessi, M.-C.; Juhan-Vague, I. PAI-1 and the Metabolic Syndrome: Links, Causes, and Consequences. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2200–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altalhi, R.; Pechlivani, N.; Ajjan, R.A. PAI-1 in Diabetes: Pathophysiology and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk-Wiązania, A.H.; Undas, A. Hypofibrinolysis in Type 2 Diabetes and Its Clinical Implications: From Mechanisms to Pharmacological Modulation. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picó, C.; Palou, M.; Pomar, C.A.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Palou, A. Leptin as a Key Regulator of the Adipose Organ. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Yabe, D. GIP and GLP-1, the Two Incretin Hormones: Similarities and Differences: Similarities and Differences of GIP and GLP-1. J. Diabetes Investig. 2010, 1, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yoder, S.M.; Yang, Q.; Kohan, A.B.; Kindel, T.L.; Wang, J.; Tso, P. Chronic High-Fat Feeding Increases GIP and GLP-1 Secretion without Altering Body Weight. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 309, G807–G815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, S.; Harada, N.; Inagaki, N. Mechanisms of Fat-Induced Gastric Inhibitory Polypeptide/Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Secretion from K Cells. J. Diabetes Investig. 2016, 7, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.M.; Grobin, W.; Track, N.S. Diets Rich in Natural Fibre Improve Carbohydrate Tolerance in Maturity-Onset, Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetics. Diabetologia 1981, 20, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasteska, D.; Harada, N.; Suzuki, K.; Yamane, S.; Hamasaki, A.; Joo, E.; Iwasaki, K.; Shibue, K.; Harada, T.; Inagaki, N. Chronic Reduction of GIP Secretion Alleviates Obesity and Insulin Resistance Under High-Fat Diet Conditions. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, J.; Buzsáki, G.; Eichenbaum, H.; Nadel, L.; Ranganath, C.; Redish, A.D. Viewpoints: How the Hippocampus Contributes to Memory, Navigation and Cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhong, Z.; Karin, M. NF-κB: A Double-Edged Sword Controlling Inflammation. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Campa Negrillo, A.; Suárez Valles, B.; Ferreira Fernández, J.J. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity in Seeds of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Foods 2021, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaberi, K.R.; Alamdari-palangi, V.; Savardashtaki, A.; Vatankhah, P.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Tajbakhsh, A.; Sahebkar, A. Modulatory Effects of Phytochemicals on Gut–Brain Axis: Therapeutic Implication. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2024, 8, 103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Kirk, R.D.; DaSilva, N.A.; Ma, H.; Seeram, N.P.; Bertin, M.J. Polyphenol Microbial Metabolites Exhibit Gut and Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability and Protect Murine Microglia against LPS-Induced Inflammation. Metabolites 2019, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Daza, M.C.; Pulido-Mateos, E.C.; Lupien-Meilleur, J.; Guyonnet, D.; Desjardins, Y.; Roy, D. Polyphenol-Mediated Gut Microbiota Modulation: Toward Prebiotics and Further. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 689456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fock, E.; Parnova, R. Mechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Protection by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Cells 2023, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, A.; Dobson, C.C.; Mottawea, W.; Buzati Pereira, B.L.; Hammami, R.; Power, K.A.; Bordenave, N. Impact of Molecular Interactions with Phenolic Compounds on Food Polysaccharides Functionality. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Rund, L.; Hutchinson, N.T.; Woods, J.A.; Steelman, A.J.; Johnson, R.W. Inhibition of Inflammatory Microglia by Dietary Fiber and Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, M.; Hao, S.; Lum, J.S.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.-F.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, K. Supplement of Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates Prevents Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Decline by Improving the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Hasselwander, S.; Li, H.; Xia, N. Effects of Different Diets Used in Diet-Induced Obesity Models on Insulin Resistance and Vascular Dysfunction in C57BL/6 Mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nutrient (g/kg) | BD TD.180554 | HF TD.180557 | HF + WK TD.180558 | HF + DK TD.180556 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | 200.0 | 265.0 | 225.0 | 226.22 |

| L-Cystine | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Corn Starch | 377.486 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Maltodextrin | 132.0 | 160.0 | 94.72 | 91.3072 |

| Sucrose | 100.0 | 92.586 | 92.586 | 92.586 |

| Lard | 0.0 | 310.0 | 310.0 | 310.0 |

| Soybean Oil | 70.0 | 30.0 | 28.33 | 28.2728 |

| Cellulose | 50.0 | 50.0 | 17.75 | 18.5 |

| Pectin | 20.0 | 20.0 | 9.2 | 10.7 |

| Mineral Mix, AIN-93G-MX (94046) | 35.0 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 48.0 |

| Vitamin Mix, AIN-93-VX (94047) | 10.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 |

| Calcium Phosphate, dibasic | 0.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| TBHQ, antioxidant | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| White Kidney Bean Powder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 150.0 | 0.0 |

| Dark Red Kidney Bean Powder | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 150.0 |

| TPC (mg GAE/g diet) | 0.24 ± 0.005 c | 0.25 ± 0.01 c | 0.34 ± 0.009 b | 0.44 ± 0.009 a |

| Contribution of total calories from each macronutrient | ||||

| Protein (% kcal) | 19.2 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 18.5 |

| Carbohydrate (% kcal) | 63.2 | 21.1 | 20.7 | 20.8 |

| Fat (% kcal) | 17.6 | 60.5 | 60.8 | 60.7 |

| Energy Density (kcal/g) | 3.7 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| BD | HF | HF + WK | HF + DK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p__Firmicutes | 31.449 ± 2.1 | 34.233 ± 1.838 | 27.984 ± 1.195 # | 32.469 ± 1.514 |

| c__Bacilli;o__Bacillales;f__Bacillaceae;__ | 0.076 ± 0.041 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| c__Bacilli;o__Lactobacillales;f__Lactobacillaceae;g__Lactobacillus | 0.266 ± 0.135 | 0.06 ± 0.012 | 0.23 ± 0.056 # | 0.251 ± 0.102 # |

| c__Clostridia;__;__;__ | 0 ± 0 | 0.084 ± 0.015 * | 0.038 ± 0.011 *# | 0.077 ± 0.019 * |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;__;__ | 3.425 ± 0.702 | 3.4 ± 0.423 | 4.543 ± 0.664 | 3.451 ± 0.321 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__;g__ | 2.775 ± 0.691 | 1.902 ± 0.391 | 0.962 ± 0.101 *# | 1.28 ± 0.25 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Lachnospiraceae;__ | 8.297 ± 0.806 | 7.543 ± 1.547 | 7.259 ± 1.035 | 10.065 ± 0.896 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Lachnospiraceae;g__Clostridium | 6.907 ± 1.347 | 5.582 ± 1.12 | 5.553 ± 0.561 | 6.738 ± 0.848 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Lachnospiraceae;g__Defluviitalea | 0.415 ± 0.067 | 0.8 ± 0.15 | 0.359 ± 0.028 # | 0.411 ± 0.064 # |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Lachnospiraceae;g__Dorea | 0.104 ± 0.021 | 0.15 ± 0.022 | 0.165 ± 0.019 | 0.248 ± 0.027 *# |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Lachnospiraceae;g__Lachnospira | 0.126 ± 0.061 | 0.86 ± 0.27 * | 0.148 ± 0.063 # | 0.083 ± 0.028 # |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Lachnospiraceae;g__Ruminococcus | 0.008 ± 0.008 | 0.011 ± 0.007 | 0.615 ± 0.171 *# | 0.386 ± 0.071 *# |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Peptococcaceae;g__rc4-4 | 0.985 ± 0.216 | 0.882 ± 0.164 | 0.373 ± 0.058 *# | 0.332 ± 0.043 *# |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Peptostreptococcaceae;__ | 0 ± 0 | 0.689 ± 0.404 | 0.148 ± 0.113 | 0.02 ± 0.02 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Ruminococcaceae;__ | 3.922 ± 1.105 | 2.584 ± 0.4 | 1.927 ± 0.228 | 2.11 ± 0.264 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Ruminococcaceae;g__ | 2.052 ± 0.265 | 4.471 ± 1.037 | 2.737 ± 0.191 | 2.934 ± 0.309 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Ruminococcaceae;g__Clostridium | 1.062 ± 0.108 | 2.812 ± 0.371 * | 1.747 ± 0.27 # | 2.165 ± 0.282 * |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Ruminococcaceae;g__Oscillospira | 0.529 ± 0.057 | 1.061 ± 0.162 * | 0.411 ± 0.048 # | 0.823 ± 0.208 |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Ruminococcaceae;g__Papillibacter | 0.033 ± 0.02 | 0 ± 0 | 0.093 ± 0.031 # | 0.229 ± 0.146 *# |

| c__Clostridia;o__Clostridiales;f__Ruminococcaceae;g__Sporobacter | 0.458 ± 0.051 | 1.334 ± 0.318 * | 0.669 ± 0.106 | 0.858 ± 0.116 * |

| p__Bacteroidetes | 59.365 ± 2.108 | 55.35 ± 1.787 | 61.383 ± 1.731 # | 58.777 ± 1.252 |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;__;__ | 0.572 ± 0.084 | 0.589 ± 0.247 | 0.812 ± 0.096 # | 0.631 ± 0.164 |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;f__Bacteroidaceae;g__Bacteroides | 23.623 ± 2.256 | 27.343 ± 1.492 | 19.546 ± 1.446 # | 18.766 ± 0.984 # |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;f__Porphyromonadaceae;g__Parabacteroides | 0.85 ± 0.138 | 0.674 ± 0.064 | 0.631 ± 0.124 | 0.4 ± 0.032 *# |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;f__Prevotellaceae;g__Prevotella | 3.112 ± 0.488 | 0.366 ± 0.13 * | 6.454 ± 0.785 *# | 3.786 ± 0.741 # |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;f__Rikenellaceae;__ | 2.911 ± 0.513 | 4.315 ± 0.85 | 9.705 ± 0.893 *# | 9.643 ± 1.044 *# |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;f__Rikenellaceae;g__Alistipes | 8.843 ± 1.032 | 11.491 ± 1.044 | 7.397 ± 0.591 # | 9.092 ± 0.996 |

| c__Bacteroidia;o__Bacteroidales;f__S24-7;g__ | 19.45 ± 1.557 | 10.569 ± 0.923 * | 16.837 ± 1.54 # | 16.456 ± 1.499 # |

| p__Deferribacteres | 4.053 ± 0.411 | 7.965 ± 0.928 * | 2.997 ± 0.545 # | 3.681 ± 0.455 # |

| c__Deferribacteres;o__Deferribacterales;f__Deferribacteraceae;g__Mucispirillum | 4.053 ± 0.411 | 7.965 ± 0.928 * | 2.997 ± 0.545 # | 3.681 ± 0.455 # |

| p__Proteobacteria | 2.133 ± 0.345 | 0.934 ± 0.244 * | 1.746 ± 0.295 # | 1.156 ± 0.241 * |

| p__Proteobacteria;c__Alphaproteobacteria;__;__;__ | 1.663 ± 0.34 | 0.917 ± 0.24 | 1.111 ± 0.291 | 0.795 ± 0.217 |

| p__Proteobacteria;c__Alphaproteobacteria;o__RF32;f__;g__ | 0.294 ± 0.191 | 0 ± 0 | 0.299 ± 0.15 # | 0.09 ± 0.057 |

| p__Proteobacteria;c__Betaproteobacteria;o__Burkholderiales;__;__ | 0.174 ± 0.059 | 0.017 ± 0.008 * | 0.335 ± 0.051 *# | 0.27 ± 0.055 # |

| p__Verrucomicrobia | 1.635 ± 0.279 | 0.68 ± 0.355 * | 1.037 ± 0.308 | 0.513 ± 0.185 * |

| c__Verrucomicrobiae;o__Verrucomicrobiales;f__Verrucomicrobiaceae;g__Akkermansia | 1.635 ± 0.279 | 0.68 ± 0.355 * | 1.037 ± 0.308 | 0.513 ± 0.185 * |

| p__Cyanobacteria | 1.319 ± 0.47 | 0.443 ± 0.176 * | 0.863 ± 0.2 | 0.521 ± 0.276 * |

| c__4C0d-2;o__YS2;f__;g__ | 1.319 ± 0.47 | 0.443 ± 0.176 * | 0.863 ± 0.2 | 0.521 ± 0.276 * |

| p__Tenericutes | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 3.844 ± 1.001 *# | 2.743 ± 0.539 *# |

| c__Mollicutes;o__Anaeroplasmatales;f__Anaeroplasmataceae;g__gut | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 3.844 ± 1.001 *# | 2.743 ± 0.539 *# |

| p__TM7 | 0.043 ± 0.019 | 0.392 ± 0.136 * | 0.142 ± 0.027 * | 0.136 ± 0.034 * |

| c__TM7-3;o__CW040;f__F16;g__ | 0.043 ± 0.019 | 0.392 ± 0.136 * | 0.142 ± 0.027 * | 0.136 ± 0.034 * |

| Sample Type | Marker | BD | HF | HF + WK | HF + DK | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | Adipose- and Endothelial-derived Hormones (pg/mL) | |||||

| Leptin | 4656 ± 958.0 b | 14,662 ± 4306 a | 12191 ± 3536 ab | 19,473 ± 4917 a | F (3, 40) = 5.434, p = 0.0031 | |

| Resistin | 30,018 ± 1046 | 37,640 ± 2143 | 35,263 ± 3802 | 30,652 ± 6398 | H(3) = 5.488, p = 0.1394 | |

| PAI-1 | 966.6 ± 48.97 a | 776.7 ± 42.69 b | 830.9 ± 45.44 ab | 817.3 ± 30.26 ab | F (3, 41) = 3.854, p = 0.0161 | |

| Gut-derived peptide hormones (pg/mL) | ||||||

| GIP | 80.71 ± 2.208 a | 70.14 ± 2.495 b | 68.49 ± 2.097 b | 67.85 ± 2.252 b | H(3) = 15.08, p = 0.0018 | |

| Ghrelin | 2474 ± 136.2 | 2227 ± 226.5 | 2087 ± 197.4 | 1779 ± 243.7 | F (3, 41) = 2.146, p = 0.1091 | |

| Biomarkers of Blood Glucose Regulation and Insulin Resistance | ||||||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 8.75 ± 0.2811 b | 10.08 ± 0.1896 a | 10.10 ± 0.2777 a | 10.30 ± 0.2585 a | F (3, 41) = 7.944, p = 0.0003 | |

| Insulin (pg/mL) | 1549 ± 151.3 | 1823 ± 108.2 | 1850 ± 114.6 | 1841 ± 123.9 | F (3, 41) = 1.347, p = 0.2724 | |

| HOMA-IR | 3.380 ± 0.3010 b | 4.975 ± 0.3583 a | 5.073 ± 0.4106 a | 5.178 ± 0.4468 a | F (3, 40) = 4.843, p = 0.0057 | |

| Adipose | Adipose- and Endothelial-derived Hormones (pg/mL) | |||||

| Leptin | 9880 ± 1324 b | 15,901 ± 1595 a | 16,700 ± 1514 a | 18,551 ± 1859 a | F (3, 40) = 5.60, p = 0.0026 | |

| Resistin | 85,102 ± 6574 a | 66,356 ± 7699 ab | 65,244 ± 7449 ab | 52,935 ± 7037 b | F (3, 41) = 3.655, p = 0.0201 | |

| PAI-1 | 634.0 ± 71.30 | 727.1 ± 80.36 | 824.4 ± 54.16 | 810.3 ± 61.29 | F (3, 41) = 2.481, p = 0.0745 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodrigue, A.F.; Pereira, B.B.; Freije, G.; Sweet, A.; Mahmoudian, L.; Aly, M.; Mahmoodianfard, S.; Kishore, L.; Audet, M.-C.; Minicucci, M.F.; et al. Varietal Differences in Kidney Beans Modulate Gut Microbiota and Inflammation During High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice. Nutrients 2026, 18, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030461

Rodrigue AF, Pereira BB, Freije G, Sweet A, Mahmoudian L, Aly M, Mahmoodianfard S, Kishore L, Audet M-C, Minicucci MF, et al. Varietal Differences in Kidney Beans Modulate Gut Microbiota and Inflammation During High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030461

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigue, Alexane F., Bruna B. Pereira, Giorgio Freije, Allison Sweet, Laili Mahmoudian, Mahmoud Aly, Salma Mahmoodianfard, Lalit Kishore, Marie-Claude Audet, Marcos F. Minicucci, and et al. 2026. "Varietal Differences in Kidney Beans Modulate Gut Microbiota and Inflammation During High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030461

APA StyleRodrigue, A. F., Pereira, B. B., Freije, G., Sweet, A., Mahmoudian, L., Aly, M., Mahmoodianfard, S., Kishore, L., Audet, M.-C., Minicucci, M. F., Pauls, K. P., & Power, K. A. (2026). Varietal Differences in Kidney Beans Modulate Gut Microbiota and Inflammation During High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice. Nutrients, 18(3), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030461