Feeding the Family—A Food Is Medicine Intervention: Preliminary Baseline Results of Clinical Data from Caregivers and Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

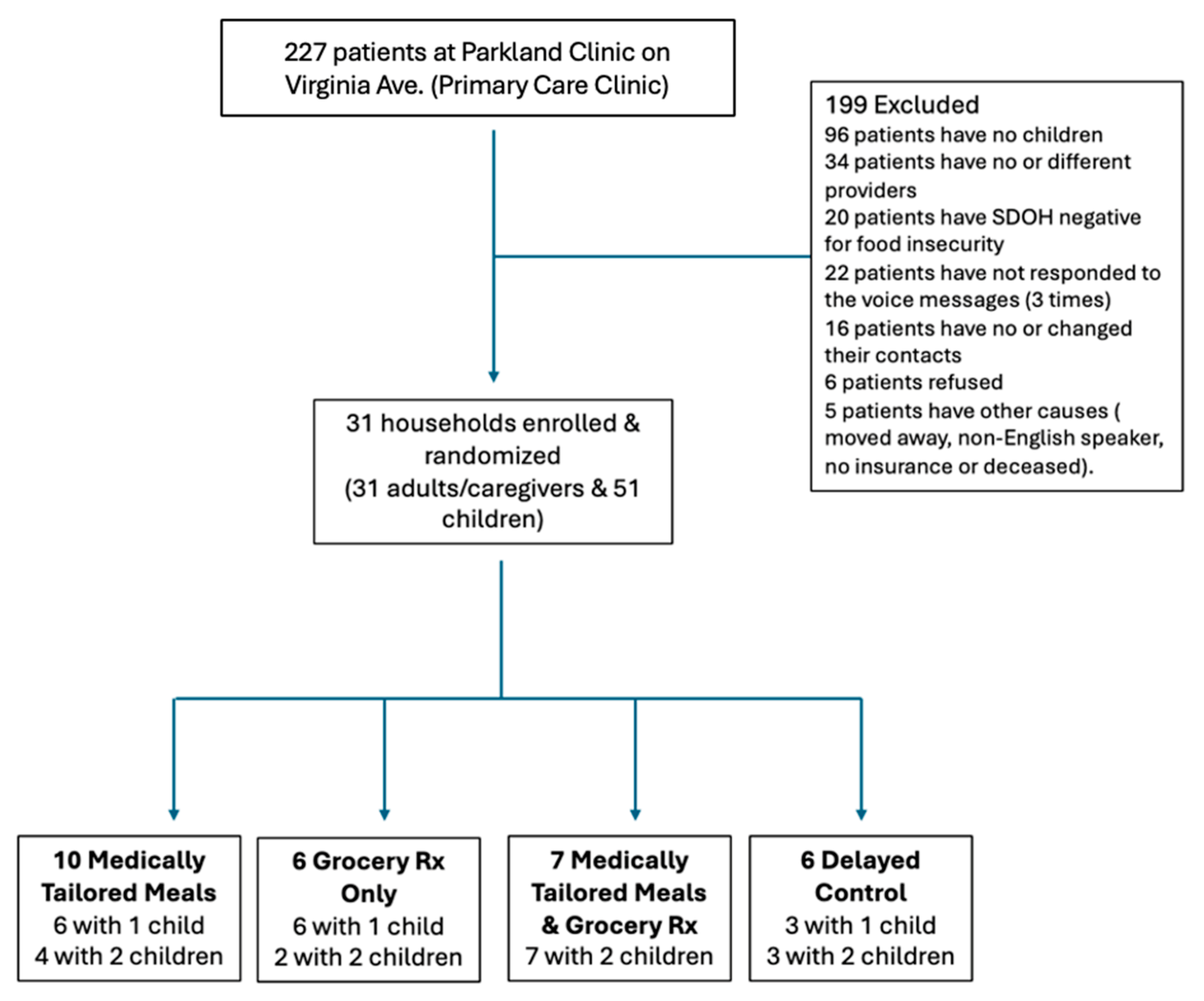

2.3. Recruitment, Consent, Assent, and Randomization

2.4. Study Arms

2.4.1. Medically Tailored Meals (MTMs)

2.4.2. Grocery Prescription (GP)

- In-store option: participants received a food benefit card—a debit-style card used by recipients to purchase eligible healthy grocery items—to be used at participating grocery stores (a supermarket retailer chain with 25 store locations across Louisville).

- Online option: participants accessed grocery benefits through an online grocery delivery platform, which allowed for home delivery of eligible healthy grocery items.

2.4.3. Combined MTMs + GP

2.4.4. Delayed Control

2.5. Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Parent–Child Biomarker Correlations

3.3. Correlations Between Caregiver Socioeconomic Factors and Child Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FIM | Food is Medicine. |

| pRCT | Pragmatic randomized controlled trial. |

| MTMs | Medically Tailored Meals. |

| GP | Grocery Prescription. |

| BMI | Body Mass Index. |

| A1c | Hemoglobin A1c. |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein. |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein. |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease. |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. |

| UofL | University of Louisville. |

| DASH | Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension. |

| EHR | Electronic Health Records. |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. |

| WIC | Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. |

| CHIP | Children’s Health Insurance Program. |

| TANF | Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. |

References

- Overview. USDA ERS—Food Security in the U.S. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Food Insecurity. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/food-insecurity#cit1 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2021, ERR-309, US Department of Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/104656/err-309.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.K.; Lammert, L.J.; Beverly, E.A. Food Insecurity and its Impact on Body Weight, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Mental Health. Curr. Cardiovasc. Risk Rep. 2021, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Javed, Z.; Taha, M.; Yahya, T.; Valero-Elizondo, J.; Brandt, E.J.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Mahajan, S.; Ali, H.-J.; Nasir, K. Food insecurity and cardiovascular disease: Current trends and future directions. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 9, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Food Insecurity and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, S.S.; Bullard, K.M.; Siegel, K.R.; Lawrence, J.M. Food insecurity, diet quality, and suboptimal diabetes management among US adults with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e003033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fram, M.S.; Ritchie, L.D.; Rosen, N.; Frongillo, E.A. Child experience of food insecurity is associated with child diet and physical activity. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, A.M.; Palakshappa, D.; Brown, C.L. Relationship between food insecurity and high blood pressure in a national sample of children and adolescents. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019, 34, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, N.M.; Wolfson, J.A.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Willett, W.C.; Leung, C.W. Food Insecurity and Ideal Cardiovascular Health Risk Factors Among US Adolescents. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agurs-Collins, T.; Alvidrez, J.; ElShourbagy Ferreira, S.; Evans, M.; Gibbs, K.; Kowtha, B.; Pratt, C.; Reedy, J.; Shams-White, M.; Brown, A.G.M. Perspective: Nutrition Health Disparities Framework: A Model to Advance Health Equity. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.X.; Morales, S.A.; Beltran, T.F. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Household Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Aspry, K.E.; Garfield, K.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Seligman, H.; Velarde, G.P.; Williams, K.; Yang, E. ACC Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section Nutrition; Lifestyle Working Group and Disparities of Care Working Group. “Food Is Medicine” Strategies for Nutrition Security and Cardiometabolic Health Equity: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, K.; Du, M.; Li, Z.; Mozaffarian, D.; Chui, K.; Shi, P.; Ling, B.; Cash, S.B.; Folta, S.C.; Zhang, F.F. Impact of Produce Prescriptions on Diet, Food Security, and Cardiometabolic Health Outcomes: A Multisite Evaluation of 9 Produce Prescription Programs in the United States. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2023, 16, e009520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.; Alsan, M.; Skelley, N.; Lu, Y.; Cawley, J. Effect of an Intensive Food-as-Medicine Program on Health and Health Care Use: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.J.; Roberto, C.A. A “Food Is Medicine” Approach to Disease Prevention: Limitations and Alternatives. JAMA 2023, 330, 2243–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, S.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Harlan, T.S.; Olstad, D.L.; Mozaffarian, D. Food is medicine: Actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare. BMJ 2020, 369, m2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Karpman, M.; Waxman, E.; Allen, E.; Gonzalez, D.; Hinojosa, S.; Kennedy, N. Public Perceptions of ‘Food Is Medicine’ Programs and Implications for Policy: Insights from the Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey and Qualitative Interviews; The Urban Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/public-perceptions-food-medicine-programs-and-implications-policy (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Food Security in Louisville. Greater Louisville Project. 2021. Available online: https://greaterlouisvilleproject.org/food-security/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- UofL Health. 2026–2028 Community Health Needs Assessment, Jefferson County; UofL Health: Louisville, KY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://uoflhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/CHNA-Jefferson-County-2026-2028-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Hager, E.R.; Quigg, A.M.; Black, M.M.; Coleman, S.M.; Heeren, T.; Rose-Jacobs, R.; Cook, J.T.; de Cuba, S.A.E.; Casey, P.H.; Chilton, M.; et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e26–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Extended BMI-for-Age (5 to 19 Years); CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/extended-bmi.htm (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Survey Tools: U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module (18-Item); Food Security in the U.S. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risks; NIH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmi_dis.htm (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Flynn, J.T.; Kaelber, D.C.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Blowey, D.; Carroll, A.E.; Daniels, S.R.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Dionne, J.M.; Falkner, B.; Flinn, S.K.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018, 71, 1269–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S20–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: Summary report. Pediatrics 2011, 128, S213–S256. [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; Goldberg, R.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/Multi-Society Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, e285–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, E.; Strand, M.F.; Lindberg, M.; Goswami, N.; Fredriksen, P.M. Variation in Child Serum Cholesterol and Prevalence of Familiar Hypercholesterolemia: The Health Oriented Pedagogical Project (HOPP). Glob. Pediatr. Health 2022, 9, 2333794X221079558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raitakari, O.T.; Juonala, M.; Kahonen, M.; Taittonen, L.; Laitinen, T.; Mäki-Torkko, N.; Järvisalo, M.J.; Uhari, M.; Jokinen, E.; Rönnemaa, T.; et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. JAMA 2003, 290, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, M.; Burch, J.; Llewellyn, A.; Griffiths, C.; Yang, H.; Owen, C.; Duffy, S.; Woolacott, N. The use of measures of obesity in childhood for predicting obesity and the development of obesity-related diseases in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 2015, 19, 1–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.; Feese, M.; Franklin, F.; Kabagambe, E.K. Body mass index and dietary intake among Head Start children and caregivers. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2011, 111, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.V.E.; Chittams, J.; Moore, R.H. Relationship between food insecurity, child weight status, and parent-reported child eating and snacking behaviors. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 22, e12177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Angell, S.Y.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Hager, K.; Moise, N.; Posner, H.; Muse, J.; Odoms-Young, A.; Ridberg, R.; et al. A Systematic Review of “Food Is Medicine” Randomized Controlled Trials for Noncommunicable Disease in the United States: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 152, e32–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Graves, L.; McGowan, B.; Mayfield, B.J.; Connolly, B.A.; Stevens, W.; Abbott, A. A Scoping Review of Household Factors Contributing to Dietary Quality and Food Security in Low-Income Households with School-Age Children in the United States. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 914–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Delahanty, L.M.; Terranova, J.; Steiner, B.; Ruazol, M.P.; Singh, R.; Shahid, N.N.; Wexler, D.J. Medically Tailored Meal Delivery for Diabetes Patients with Food Insecurity: A Randomized Cross-over Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyonnais, M.J.; Kaur, A.P.; Rafferty, A.P.; Johnson, N.S.; Jilcott Pitts, S. A Mixed-Methods Examination of the Impact of the Partnerships to Improve Community Health Produce Prescription Initiative in Northeastern North Carolina. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muleta, H.; Fischer, L.K.; Chang, M.; Kim, N.; Leung, C.W.; Obudulu, C.; Essel, K. Pediatric produce prescription initiatives in the U.S.: A scoping review. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 95, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.E.; Cook, M.; Reasoner, T.; McLean, A.; Webb Girard, A. Engagement in a pilot produce prescription program in rural and urban counties in the Southeast United States. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1390737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Lyles, C.; Marshall, M.B.; Prendergast, K.; Smith, M.C.; Headings, A.; Bradshaw, G.; Rosenmoss, S.; Waxman, E. A Pilot Food Bank Intervention Featuring Diabetes-Appropriate Food Improved Glycemic Control Among Clients In Three States. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, R. Food is Medicine Initiative for Mitigating Food Insecurity in the United States. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2024, 57, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Berkowitz, S.A. Aligning Programs and Policies to Support Food Security and Public Health Goals in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, K.; Kummer, C.; Lewin-Zwerdling, A.; Li, Z. Food Is Medicine Research Action Plan. 2024. Available online: https://aspenfood.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Food-is-Medicine-Action-Plan-2024-Final.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Carpenter, A.; Kuchera, A.M.; Krall, J.S. Connecting Families at Risk for Food Insecurity With Nutrition Assistance Through a Clinical-Community Direct Referral Model. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Caregiver | Child 1 | Child 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 6 (19.4) | 11 (35.5) | 13 (65) |

| Female | 25 (80.4) | 20 (64.5) | 7 (35) |

| Race | |||

| Black of African American | 29 (93.5) | 27 (87) | 20 (100) |

| More than one race | 1 (3.2) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (3.2) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Annual Household Income | |||

| <USD 10,000 | 18 (58.1) | ||

| USD 10,000–USD 34,999 | 8 (25.8) | ||

| USD 35,000–USD 50,000 | 5 (16.1) | ||

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed for wages | 11 (35.5) | ||

| Self-employed | 2 (6.5) | ||

| Out of work | 8 (25.8) | ||

| Unable to work (disabled) | 6 (19.4) | ||

| Education Level | |||

| 9th–12th grade; no diploma | 3 (9.7) | ||

| High school grad or GED | 9 (29.0) | ||

| Completed vocational, trade, or some college | 16 (51.6) | ||

| Some college, no degree | 11 (35.5) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 3 (9.6) | ||

| Household Size | |||

| Average | 3.77 (1.2 SD) | ||

| Nutrition Assistance | |||

| SNAP | 23 (74.2) | ||

| WIC | 2 (6.5) | ||

| Government Assistance | |||

| CHIP | 1 (3.2) | ||

| TANF | 3 (9.7) | ||

| Medicaid | 22 (71.0) | ||

| None of the above | 6 (19.4) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6.5) | ||

| Financial Strain | |||

| Sometimes or rarely | 21 (67.7) | ||

| Often or always | 10 (32.2) | ||

| Food Security Level | Household | Adult | Child 1 |

| High | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (19.4) |

| Marginal | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Low | 9 (29.0) | 8 (25.8) | 15 (48.4) |

| Very Low | 19 (61.3) | 18 (58.1) | 8 (25.8) |

| Incomplete | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) |

| Child 1 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | BP (Systolic) | BP (Diastolic) | A1c | Cholesterol | HDL | LDL | Triglycerides | ||||||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | ||

| Caregiver | BMI | 0.59 | 0.042 | 0.35 | 0.269 | −0.003 | 0.991 | 0.27 | 0.391 | −0.37 | 0.240 | −0.40 | 0.195 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.31 | 0.319 |

| BP (systolic) | 0.44 | 0.147 | −0.31 | 0.323 | −0.41 | 0.189 | 0.18 | 0.577 | −0.45 | 0.144 | −0.30 | 0.350 | 0 | 1 | −0.09 | 0.779 | |

| BP (diastolic) | 0.44 | 0.156 | 0.06 | 0.857 | −0.27 | 0.391 | 0.36 | 0.256 | −0.06 | 0.861 | 0.35 | 0.259 | −0.8 | 0.2 | −0.20 | 0.538 | |

| A1c | 0.20 | 0.548 | 0.30 | 0.375 | −0.27 | 0.414 | 0.40 | 0.227 | −0.08 | 0.815 | −0.46 | 0.155 | 0.11 | 0.895 | 0.60 | 0.052 | |

| Cholesterol | −0.62 | 0.032 | −0.05 | 0.880 | 0.19 | 0.555 | −0.40 | 0.201 | 0.55 | 0.065 | 0.46 | 0.135 | 0.8 | 0.2 | −0.09 | 0.770 | |

| HDL | −0.07 | 0.837 | 0.07 | 0.820 | 0.19 | 0.562 | 0.16 | 0.620 | 0.33 | 0.290 | 0.55 | 0.061 | −1 | 0 | −0.35 | 0.269 | |

| LDL | −0.34 | 0.304 | −0.22 | 0.509 | 0.32 | 0.331 | −0.79 | 0.004 | 0.26 | 0.432 | −0.21 | 0.526 | 1 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.894 | |

| Triglycerides | −0.12 | 0.704 | 0.45 | 0.144 | −0.12 | 0.720 | 0.11 | 0.723 | −0.11 | 0.729 | −0.43 | 0.159 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.66 | 0.018 | |

| Child 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juice Intake | Fruit Intake | Leafy Greens | Vegetables | Food Security Score | Food Security Category | |||||||||||||

| Caregiver | H | df | p | H | df | p | H | df | p | H | df | p | H | df | p | H | df | p |

| Household Income | 0.19995 | 4 | 0.9953 | 0.24907 | 4 | 0.9929 | 7.679 | 4 | 0.1041 | 0.12424 | 4 | 0.9981 | 3.2306 | 4 | 0.52 | 1.9964 | 4 | 0.7364 |

| Education Level | 6.9724 | 6 | 0.3234 | 5.0808 | 6 | 0.5335 | 4.1591 | 6 | 0.6552 | 6.7935 | 6 | 0.3404 | 6.7293 | 6 | 0.3466 | 1.8793 | 6 | 0.9305 |

| Financial Strain | 6.4495 | 3 | 0.09168 | 5.6793 | 3 | 0.1283 | 3.1363 | 3 | 0.3711 | 5.7779 | 3 | 0.1229 | 2.2733 | 3 | 0.5176 | 0.8331 | 3 | 0.8415 |

| Food Assistance | 1.6865 | 2 | 0.4303 | 5.4971 | 2 | 0.06402 | 1.3795 | 2 | 0.5017 | 6.1642 | 2 | 0.04586 | 2.5604 | 2 | 0.278 | 0.66318 | 2 | 0.7178 |

| Government Assistance | 1.3435 | 2 | 0.5108 | 1.4885 | 2 | 0.4751 | 0.94317 | 2 | 0.624 | 3.6653 | 2 | 0.16 | 0.50013 | 2 | 0.7787 | 0.023248 | 2 | 0.9884 |

| Food Security Score | 7.5738 | 9 | 0.5776 | 7.832 | 9 | 0.5512 | 16.012 | 9 | 0.06664 | 8.9647 | 9 | 0.4405 | 18.307 | 9 | 0.03177 | 18.436 | 9 | 0.03044 |

| Food Security Category | 2.0954 | 3 | 0.5529 | 1.5489 | 3 | 0.671 | 5.0356 | 3 | 0.1692 | 2.3207 | 3 | 0.5086 | 16.065 | 3 | 0.0011 | 17.046 | 3 | 0.0006916 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Drucker, G.; Mayfield, C.; Steeves, E.A.; Maksi, S.; Underwood, T.; Brown, J.; Frick, M.; Gustafson, A. Feeding the Family—A Food Is Medicine Intervention: Preliminary Baseline Results of Clinical Data from Caregivers and Children. Nutrients 2026, 18, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020354

Drucker G, Mayfield C, Steeves EA, Maksi S, Underwood T, Brown J, Frick M, Gustafson A. Feeding the Family—A Food Is Medicine Intervention: Preliminary Baseline Results of Clinical Data from Caregivers and Children. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020354

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrucker, Gabriela, Christa Mayfield, Elizabeth Anderson Steeves, Sara Maksi, Tabitha Underwood, Julie Brown, Marissa Frick, and Alison Gustafson. 2026. "Feeding the Family—A Food Is Medicine Intervention: Preliminary Baseline Results of Clinical Data from Caregivers and Children" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020354

APA StyleDrucker, G., Mayfield, C., Steeves, E. A., Maksi, S., Underwood, T., Brown, J., Frick, M., & Gustafson, A. (2026). Feeding the Family—A Food Is Medicine Intervention: Preliminary Baseline Results of Clinical Data from Caregivers and Children. Nutrients, 18(2), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020354