A Comparison of Marine and Non-Marine Magnesium Sources for Bioavailability and Modulation of TRPM6/TRPM7 Gene Expression in a Caco-2 Epithelial Cell Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composition and XRD Analysis of Inorganic Magnesium Sources

2.2. Surface Area Analysis

2.3. In Vitro Bioavailability Method

2.3.1. In Vitro Digestion of Mg2+ Sources

2.3.2. Caco-2 Cell Monolayer Model

2.3.3. Evaluation of Barrier Integrity, Active Transport Functionality, and Mg2+ Bioavailability

2.4. Gene Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Composition Analysis of Tested Magnesium Supplements

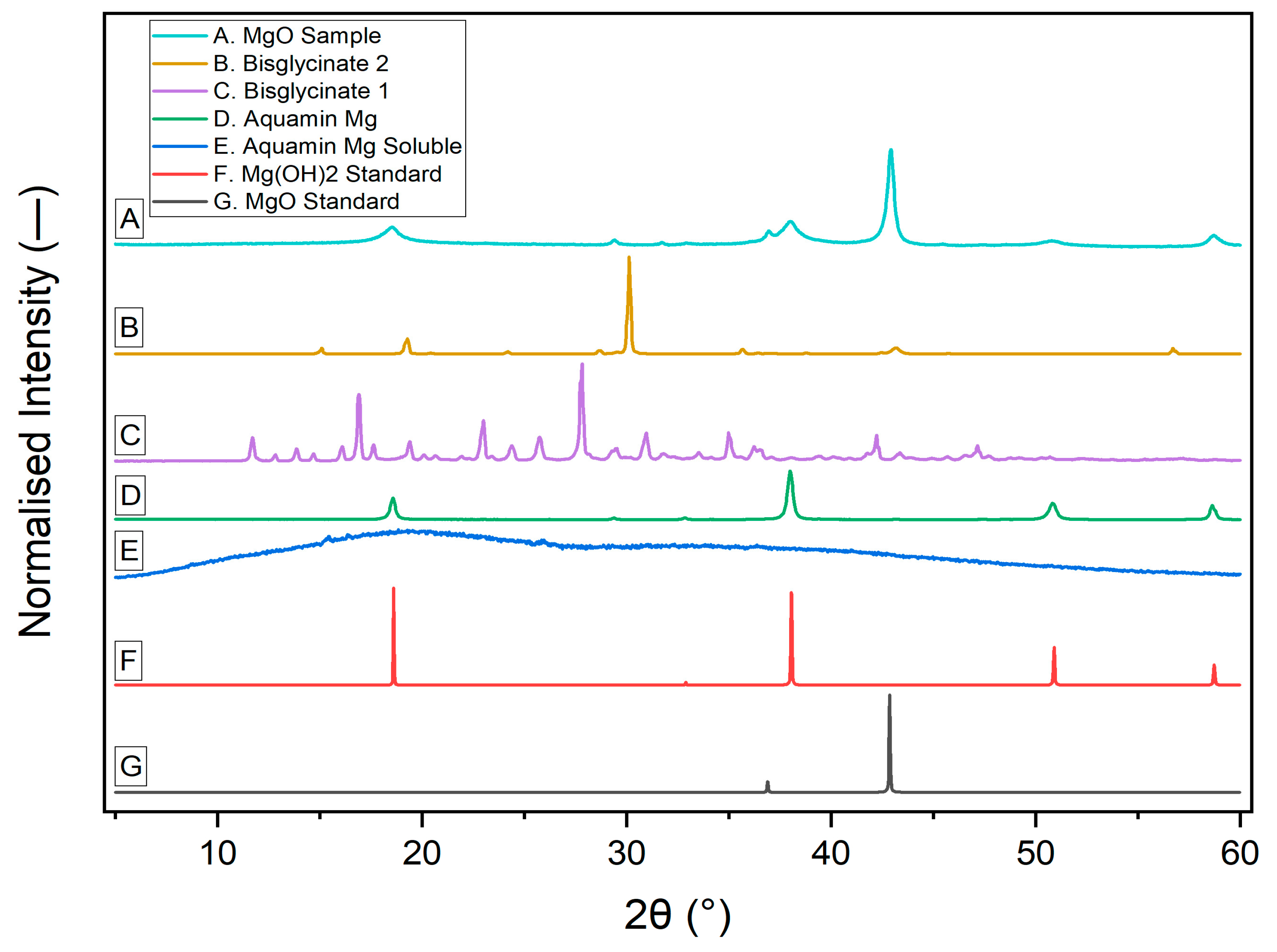

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Pattern of Different Mg2+ Sources

3.3. Surface Area

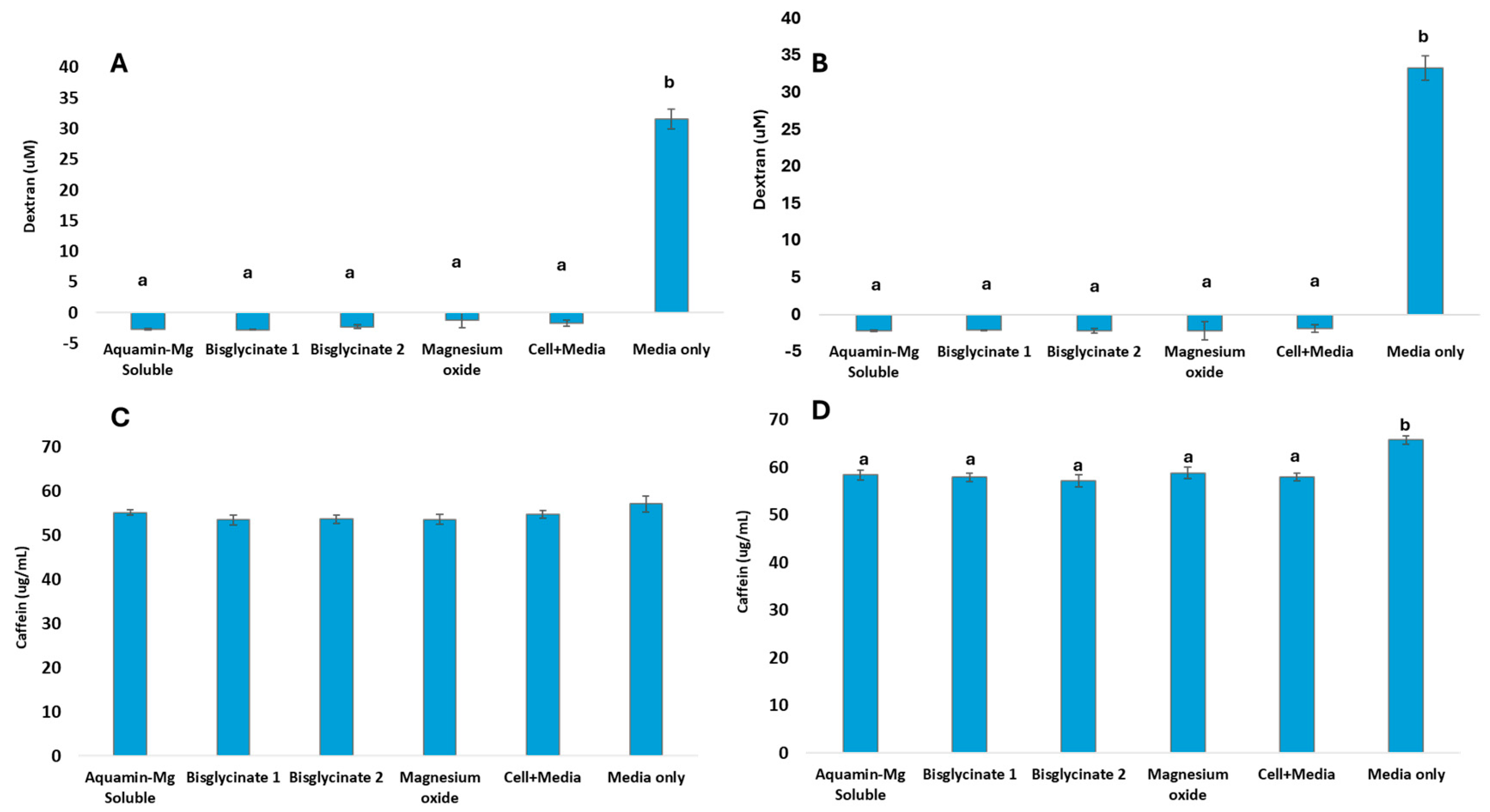

3.4. Evidence of Barrier Integrity and Active Transport Across Caco-2 Monolayer

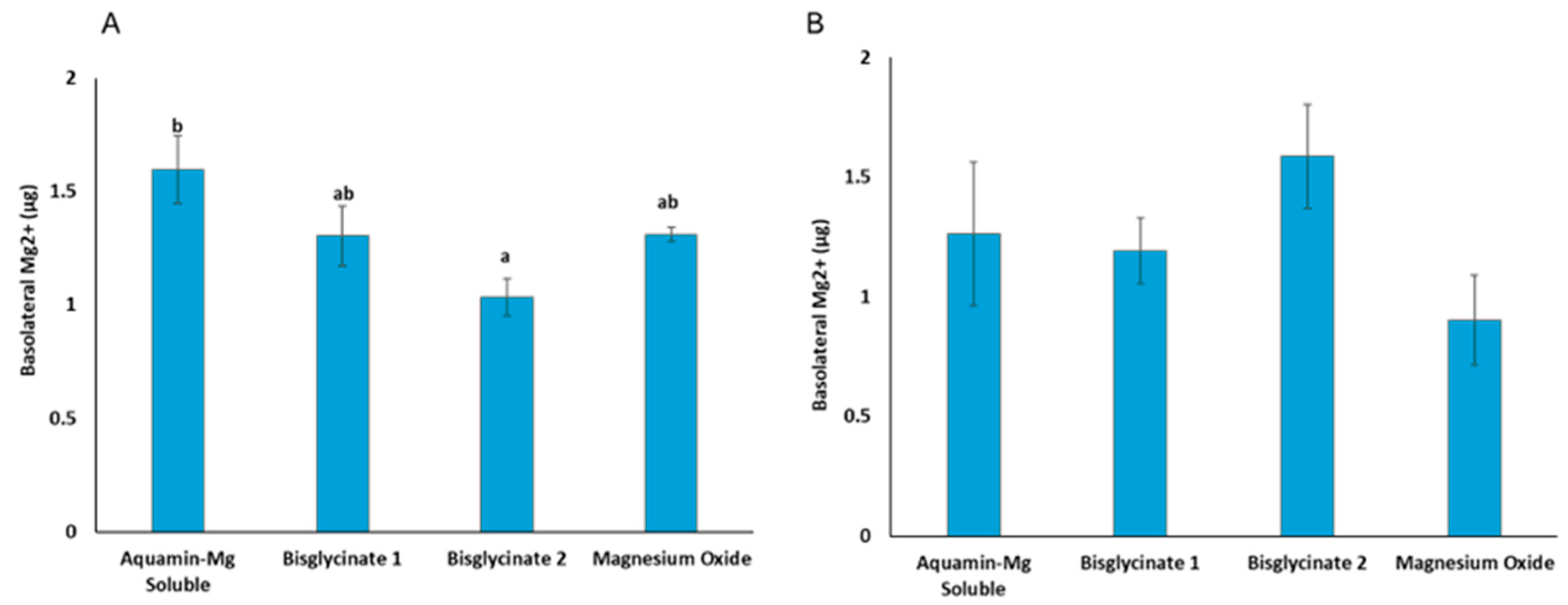

3.5. Bioavailable Mg2+

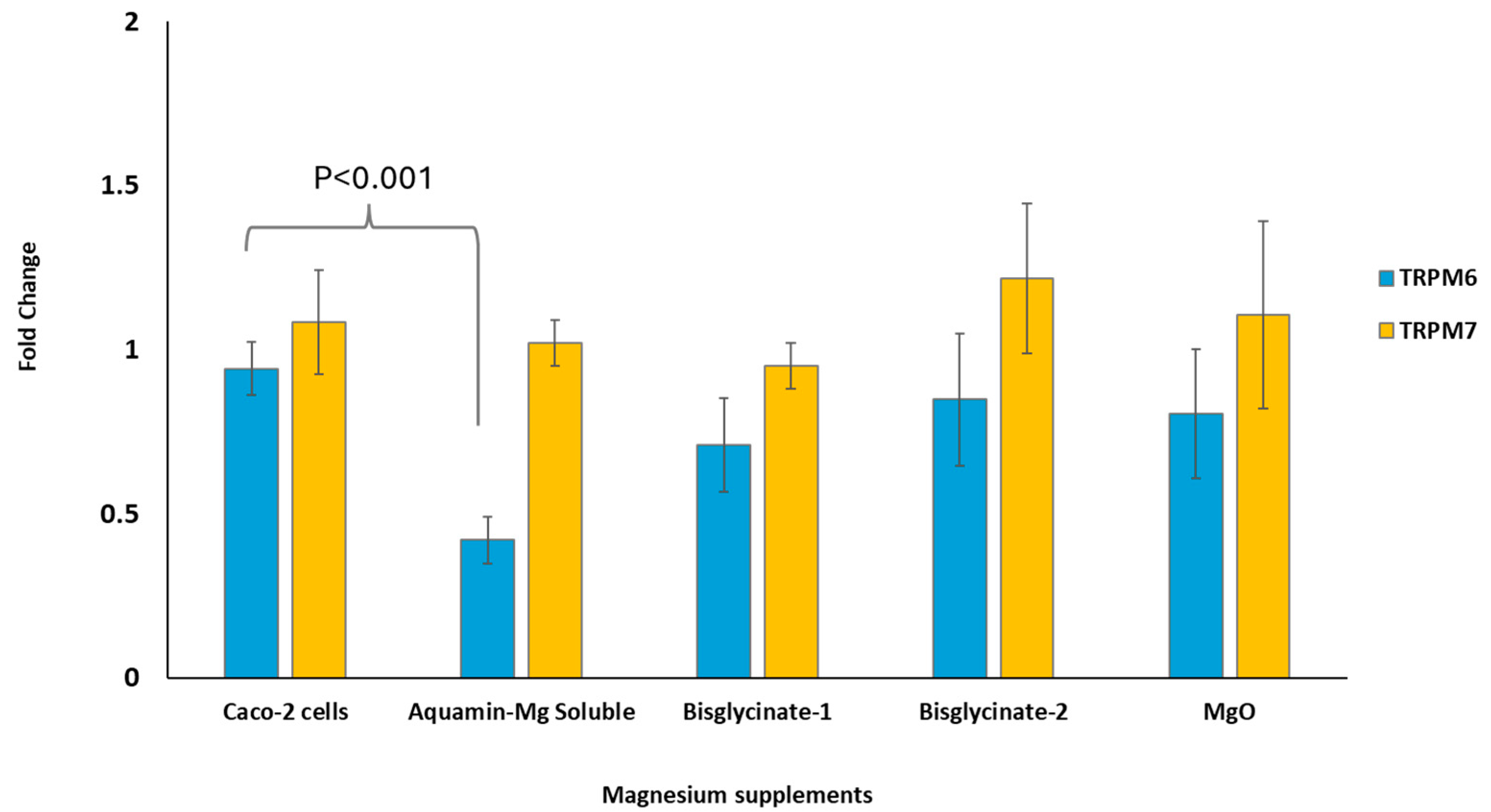

3.6. TRPM6 and TRPM7 Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costello, R.; Wallace, T.C.; Rosanoff, A. Magnesium. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; O’kEefe, J.H.; Wilson, W. Subclinical Magnesium Deficiency: A Principal Driver of Cardiovascular Disease and a Public Health Crisis. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlach, J. Recommended dietary amounts of magnesium: Mg RDA. Magnes Res. 1989, 2, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costello, R.B.; Elin, R.J.; Rosanoff, A.; Wallace, T.C.; Guerrero-Romero, F.; Hruby, A.; Lutsey, P.L.; Nielsen, F.H.; Rodriguez-Moran, M.; Song, Y.; et al. Perspective: The Case for an Evidence-Based Reference Interval for Serum Magnesium: The Time Has Come. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragossian, A.; Bashir, K.; Bhutta, B.S.; Friede, R. Hypomagnesemia. 30 November 2023. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ehrenpreis, E.D.; Jarrouj, G.; Meader, R.; Wagner, C.; Ellis, M. A comprehensive review of Hypomagnesemia. Disease-a-Month 2022, 68, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, Y.; Fujii, N.; Shoji, T.; Hayashi, T.; Rakugi, H.; Isaka, Y. Hypomagnesemia Is a Significant Predictor of Cardiovascular and Non-Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, V.D.; O’gorman, D.M.; O’brien, N.M.; Hyland, N.P. Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of a Marine-Derived Multimineral, Aquamin-Magnesium. Nutrients 2018, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyselovič, J.; Chomanicová, N.; Adamičková, A.; Valášková, S.; Šalingová, B.; Gažová, A. A New Caco-2 Cell Model of in Vitro Intestinal Barrier: Application for the Evaluation of Magnesium Salts Absorption. Physiol. Res. 2021, 70, S31–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappeler, D.; Heimbeck, I.; Herpich, C.; Naue, N.; Höfler, J.; Timmer, W.; Michalke, B. Higher Bioavailability of Magnesium Citrate as Compared to Magnesium Oxide Shown by Evaluation of Urinary Excretion and Serum Levels after Single-Dose Administration in a Randomized Cross-over Study. BMC Nutr. 2017, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.F.; Marakis, G.; Christie, S.; Byng, M. Mg citrate found more bioavailable than other Mg preparations in a randomised, double-blind study. Magnes Res. 2003, 16, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Firoz, M.; Graber, M. Bioavailability of US commercial magnesium preparations. Magnes Res. 2001, 14, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schuette, S.A.; Lashner, B.A.; Janghorbani, M. Bioavailability of Magnesium Diglycinate vs. Magnesium Oxide in Patients with Ileal Resection. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 1994, 18, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Ying, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q. Differentiated caco-2 cell models in food-intestine interaction study: Current applications and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Amp; Technol. 2021, 107, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Habicht, J.-P.; Miller, D.D.; Glahn, R.P. An in vitro digestion/Caco-2 cell culture system accurately predicts the effects of ascorbic acid and polyphenolic compounds on iron bioavailability in humans. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2717–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, K.D.; Ana, C.A.S.; Porter, J.L.; Fordtran, J.S. Intestinal absorption of magnesium from food and supplements. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.-J.; Ritchie, G.; Kerstan, D.; Kang, H.S.; Cole, D.E.C.; Quamme, G.A. Magnesium transport in the renal distal convoluted tubule. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 51–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubanov, V.; Gudermann, T.; Schlingmann, K.P. Essential role for TRPM6 in epithelial magnesium transport and body magnesium homeostasis. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2005, 451, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, N.S.; Kazi, A.A.; Yee, R.K. Cellular and developmental biology of TRPM7 channel-kinase: Implicated roles in cancer. Cells 2014, 3, 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlingmann, K.P.; Waldegger, S.; Konrad, M.; Chubanov, V.; Gudermann, T. TRPM6 and trpm7—Gatekeepers of human magnesium metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2007, 1772, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C.; Perraud, A.-L.; Johnson, C.O.; Inabe, K.; Smith, M.K.; Penner, R.; Kurosaki, T.; Fleig, A.; Scharenberg, A.M. Regulation of vertebrate cellular mg2+ homeostasis by TRPM7. Cell 2003, 114, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voets, T.; Nilius, B.; Hoefs, S.; van der Kemp, A.W.C.M.; Droogmans, G.; Bindels, R.J.; Hoenderop, J.G. TRPM6 forms the mg2+ influx channel involved in intestinal and renal mg2+ absorption. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondón, L.J.; Groenestege, W.M.T.; Rayssiguier, Y.; Mazur, A. Relationship between low magnesium status and TRPM6 expression in the kidney and large intestine. Am. J. Physiol. -Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 294, R2001–R2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenestege, W.M.T.; Hoenderop, J.G.; van den Heuvel, L.; Knoers, N.; Bindels, R.J. The epithelial mg2+ channel transient receptor potential melastatin 6 is regulated by dietary mg2+ content and estrogens. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Angelen, A.A.; San-Cristobal, P.; Pulskens, W.P.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Bindels, R.J. The impact of dietary magnesium restriction on magnesiotropic and calciotropic genes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2983–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowley, A.; Long-Smith, C.M.; Demehin, O.; Nolan, Y.; O’COnnell, S.; O’GOrman, D.M. The bioaccessibility and tolerability of marine-derived sources of magnesium and calcium. Methods 2024, 226, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petseva, V. The Physiochemical and Biological Characterization of Nanostructured Materials Derived from Natural Processes, Research Repository UCD. 2022. Available online: https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/entities/publication/80e568d1-0853-4906-bfed-559513e2b0eb (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Aljofan, M.; Alkhamaisah, S.; Younes, K.; Gaipov, A. Development and Validation of a Simple and Sensitive HPLC Method for the Determination of Liquid Form of Therapeutic Substances. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2019, 16, em166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Davidsson, L.; Walczyk, T.; Hurrell, R.F. Phytic acid added to white-wheat bread inhibits fractional apparent magnesium absorption in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Moreno, M.; Garcés-Rimón, M.; Miguel, M. Antinutrients: Lectins, goitrogens, phytates and oxalates, friends or Foe? J. Funct. Foods 2022, 89, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongioanni, A.; Bueno, M.S.; Mezzano, B.A.; Longhi, M.R.; Garnero, C. Pharmaceutical crystals: Development, optimization, characterization and biopharmaceutical aspects. In Crystal Growth and Chirality—Technologies and Applications [Preprint]; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hate, S.S.; Reutzel-Edens, S.M.; Taylor, L.S. Absorptive dissolution testing: An improved approach to study the impact of residual crystallinity on the performance of amorphous formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcotte, A.R.; Anbar, A.D.; Majestic, B.J.; Herckes, P. Mineral dust and iron solubility: Effects of composition, particle size, and surface area. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, P.; Ro, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, H.; Cho, J.M.; Yun, G.; Lee, J. Pharmaceutical Particle Technologies: An approach to improve drug solubility, dissolution and bioavailability. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.E.; Shea, K.; Ford, K.A. Unraveling caco-2 cells through functional and transcriptomic assessments. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 156, 105771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chow, E.C.; Liu, S.; Du, Y.; Pang, K.S. The Caco-2 cell monolayer: Usefulness and limitations. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Amp; Toxicol. 2008, 4, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössig, A.; Hill, K.; Nörenberg, W.; Weidenbach, S.; Zierler, S.; Schaefer, M.; Gudermann, T.; Chubanov, V. Pharmacological agents selectively acting on the channel moieties of TRPM6 and TRPM7. Cell Calcium 2022, 106, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.-G.; Rios, F.J.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. TRPM7, magnesium, and signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouadon, E.; Lecerf, F.; German-Fattal, M. Differential effects of cyclosporin A and tacrolimus on magnesium influx in caco2 cells. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 15, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; You, J.; Zhao, N.; Xu, H. Magnesium regulates endothelial barrier functions through TRPM7, MAGT1, and S1P1. Advanced Science 2019, 6, 1901166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadezhdin, K.D.; Correia, L.; Narangoda, C.; Patel, D.S.; Neuberger, A.; Gudermann, T.; Kurnikova, M.G.; Chubanov, V.; Sobolevsky, A.I. Structural mechanisms of TRPM7 activation and inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, S.; Zierler, S.; Zaißerer, J.; Schredelseker, J.; Gudermann, T.; Chubanov, V. TRPM6 and TRPM7 differentially contribute to the relief of heteromeric TRPM6/7 channels from inhibition by cytosolic mg2+ and mg·atp. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.; Narangoda, C.; Nörenberg, W.; Egawa, M.; Rössig, A.; Leonhardt, M.; Schaefer, M.; Zierler, S.; Kurnikova, M.G.; Gudermann, T.; et al. Structural mechanism of TRPM7 channel regulation by intracellular magnesium. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter (%w/w) | Aquamin Mg | Bisglycinate 1 | Bisglycinate 2 | Magnesium Oxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic | 23.25 ± 0.05 a | 26.92 ± 0.46 b | 36.93 ± 0.13 c | 79.27 ± 0.33 d |

| Organic | 76.75 ± 0.06 d | 73.08 ± 0.46 c | 63.07 ± 0.13 b | 20.73 ± 0.33 a |

| Mg2+ | 10.90 ± 0.50 a | 12.11 ± 0.37 a | 20.62 ± 1.96 b | 40.82 ± 1.51 c |

| Other inorganic | 12.30 ± 0.50 a | 14.81 ± 0.37 b | 16.31 ± 1.96 b | 38.45 ± 1.51 c |

| Sample Total Pore | Surface Area (m2/g) | Correlation Coeff | Pore Volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquamin Mg Soluble | 2 | 0.9972 | 0.002 |

| Mg Bisglycinate 1 | 9 | 0.9999 | 0.036 |

| Mg Bisglycinate 2 | 7 | 0.9999 | 0.042 |

| MgO | 14 | 0.9999 | 0.207 |

| Aquamin Mg | 15 | 0.9999 | 0.079 |

| Source of Variation | Basolateral Mg2+ Transport (µg) |

|---|---|

| Food | p = 0.512 |

| Source | p = 0.259 |

| Food × Source | p = 0.026 |

| Food | |

| Yes | 1.31 ± 0.07 |

| No | 1.24 ± 0.08 |

| Magnesium Source | |

| Aquamin Mg Soluble | 1.43 ± 0.22 |

| Mg Bisglycinate 1 | 1.25 ± 0.14 |

| Mg Bisglycinate 2 | 1.31 ± 0.15 |

| Magnesium Oxide | 1.11 ± 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Demehin, O.A.; Ryan, M.; Higgins, T.; Moura Motta, B.; Jähnichen, T.; O’Connell, S. A Comparison of Marine and Non-Marine Magnesium Sources for Bioavailability and Modulation of TRPM6/TRPM7 Gene Expression in a Caco-2 Epithelial Cell Model. Nutrients 2026, 18, 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020324

Demehin OA, Ryan M, Higgins T, Moura Motta B, Jähnichen T, O’Connell S. A Comparison of Marine and Non-Marine Magnesium Sources for Bioavailability and Modulation of TRPM6/TRPM7 Gene Expression in a Caco-2 Epithelial Cell Model. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020324

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemehin, Olusoji A., Michelle Ryan, Tommy Higgins, Breno Moura Motta, Tim Jähnichen, and Shane O’Connell. 2026. "A Comparison of Marine and Non-Marine Magnesium Sources for Bioavailability and Modulation of TRPM6/TRPM7 Gene Expression in a Caco-2 Epithelial Cell Model" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020324

APA StyleDemehin, O. A., Ryan, M., Higgins, T., Moura Motta, B., Jähnichen, T., & O’Connell, S. (2026). A Comparison of Marine and Non-Marine Magnesium Sources for Bioavailability and Modulation of TRPM6/TRPM7 Gene Expression in a Caco-2 Epithelial Cell Model. Nutrients, 18(2), 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020324