Magnesium and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Narrative Practical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preclinical Evidence

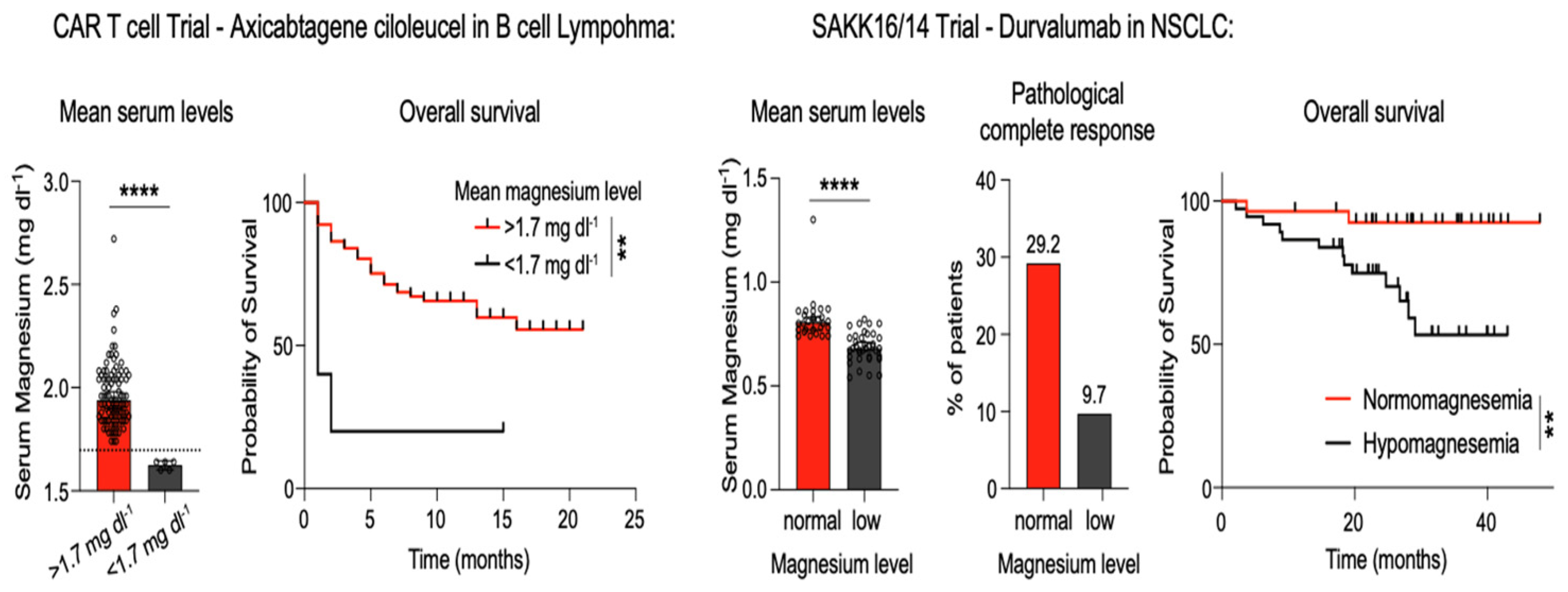

3. Clinical Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Mg2+ | Magnesium; |

| NKs | Natural killer cells; |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus; |

| ICBs | Immune checkpoint blockers. |

References

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Magnesium and the Hallmarks of Aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapani, V.; Wolf, F.I. Dysregulation of Mg2+ homeostasis contributes to the acquisition of cancer hallmarks. Cell Calcium 2019, 83, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashique, S.; Kumar, S.; Hussain, A.; Mishra, N.; Garg, A.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Farid, A.; Gupta, G.; Dua, K.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. A narrative review on the role of magnesium in immune regulation, inflammation, infectious diseases, and cancer. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 74, Erratum in J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwalfenberg, G.K.; Genuis, S.J. The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare. Scientifica 2017, 2017, 4179326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlach, J.; Bara, M.; Guiet-Bara, A.; Collery, P. Relationship between magnesium, cancer, and carcinogenic or anti-cancer metals. Anti-Cancer Res. 1986, 6, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni, S.; Maier, J.A. Magnesium and cancer: A dangerous liaison. Magnes. Res. 2011, 24, S92–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambataro, D.; Scandurra, G.; Scarpello, L.; Gebbia, V.; Dominguez, L.J.; Valerio, M.R. A Practical Narrative Review on the Role of Magnesium in Cancer Therapy. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, A.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Lenardo, M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: From T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, N.; Yueqing, C.; Abbas, M.; Zafar, H.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, T.; Ahmed, M.; Raza, F.; Zhou, X. Understanding of Immune Escape Mechanisms and Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 8901326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, N. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanisms and cutting-edge therapeutic approaches. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, F.; Vaughn, J.L.; Zhu, H.; Dickerson, J.C.; Sayegh, H.E.; Brongiel, S.; Baldwin, E.; Kier, M.W.; Zaemes, J.; Hearn, C.; et al. Inpatient Immunotherapy Outcomes Study: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, 21, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, L. Magnesium: Essential for T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulou, C.; George, A.B.; Masutani, E.; Cannons, J.L.; Ravell, J.C.; Yamamoto, T.N.; Smelkinson, M.G.; Jiang, P.D.; Matsuda-Lennikov, M.; Reilley, J.; et al. Mg2+ regulation of kinase signaling and immune function. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 1828–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigne-Delalande, B.; Lenardo, M.J. Divalent cation signaling in immune cells. Trends Immunol. 2014, 35, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigne-Delalande, B.; Li, F.Y.; O’Connor, G.M.; Lukacs, M.J.; Jiang, P.; Zheng, L.; Shatzer, A.; Biancalana, M.; Pittaluga, S.; Matthews, H.F.; et al. Mg2+ regulates cytotoxic functions of NK and CD8 T cells in chronic EBV infection through NKG2D. Science 2013, 341, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, N.K.; Kelleher, D. Not Just an Adhesion Molecule: LFA-1 Contact Tunes the T Lymphocyte Program. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötscher, J.; Martí, I.; Líndez, A.A.; Kirchhammer, N.; Cribioli, E.; Giordano Attianese, G.M.P.; Trefny, M.P.; Lenz, M.; Rotschild, S.I.; Strati, P.; et al. Magnesium sensing via LFA-1 regulates CD8+ T cell effector function. Cell 2022, 185, 585–602.e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Zhang, C.; Pan, X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, J.; Yang, G. Immunomodulatory metal-based biomaterials for cancer immunotherapy. J. Control Release 2024, 375, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wei, Y.; Yang, H. Mg alloys with antitumor and anticorrosion properties for orthopedic oncology: A review from mechanisms to application strategies. APL Bioeng. 2024, 8, 021504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Wang, Y.; Zan, R.; Wu, H.; Sun, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, R.; Song, Y.; Ni, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Biodegradable Mg Implants Suppress the Growth of Ovarian Tumor. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, W.; Liu, C.; He, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Sui, K.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Yang, K.; et al. Anticancer Effect of Biodegradable Magnesium on Hepatobiliary Carcinoma: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 2774–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Fan, K.; Zan, R.; Gong, Z.J.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Jiang, H.; Lou, J.; Ni, J.; et al. Degradable magnesium implants inhibit gallbladder cancer. Acta Biomateralia 2021, 128, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yang, H.; Shi, L.; Wang, T.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, T.; Han, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, W.; Hu, J. Enhancing Corrosion Resistance, Osteoinduction, and Antibacterial Properties by Zn/Sr Additional Surface Modification of Magnesium Alloy. ACS Biomater. Sci Eng. 2018, 4, 4289–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Onuma, K.; Sogo, Y.; Ohno, T.; Ito, A. Zn- and Mg- containing tricalcium phosphates-based adjuvants for cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Mao, J.; Li, Q.; Gong, S. Controlled release of manganese and magnesium ions by microsphere-encapsulated hydrogel enhances cancer immunotherapy. J. Control Release 2024, 372, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Qin, H.; An, Z. Magnesium enhances the chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting activated macrophage-induced inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Li, X.; Xu, M.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Niu, X. In vitro immunomodulation of magnesium on monocytic cell toward anti-inflammatory macrophages. Regen. Biomater. 2020, 7, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrumaihi, F. The Multi-Functional Roles of CCR7 in Human Immunology and as a Promising Therapeutic Target for Cancer Therapeutics. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 834149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Gao, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Lu, K.; Song, Z.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Han, X.; Li, L.; et al. Elevated serum magnesium levels prompt favorable outcomes in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockers. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 213, 115069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Lin, Y.; Li, C.; Shen, Q.; Ding, J.; Li, T.; Lu, D.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; et al. Preoperative serum magnesium level as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in locally advanced gastric cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 23, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laragione, T.; Harris, C.; Azizgolshani, N.; Beeton, C.; Bongers, G.; Gulko, P.S. Magnesium increases numbers of Foxp3+ Treg cells and reduces arthritis severity and joint damage in an IL-10-dependent manner mediated by the intestinal microbiome. EBioMedicine 2023, 92, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Pidgeon, R.; Maleki Vareki, S.; Messaoudene, M.; Castagner, B.; Routy, B. The gut microbiome as a target incancer immunotherapy: Opportunities and challenges for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, M.R.; Scandurra, G.; Greco, M.; Gebbia, V.; Piazza, D.; Sambataro, D. A Survey on the Prescribing Orientation Towards Complementary Therapies Among Oncologists in Italy: Symptoms and Unmet Patient Needs. In Vivo 2025, 39, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; You, X.; Yang, L.; Zou, X.; Sui, B. Boosting immune responses in lung tumor immune microenvironment: A comprehensive review of strategies and adjuvants. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 43, 280–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.T.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.J.; He, W.; Fan, X.J.; Wan, X.B. Turning cold tumors into hot tumors to ignite immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Yu, C.; Hu, Z.; Feng, L.; Yang, P. Magnesium-based nanomaterials for cancer therapy: Unraveling mechanisms and current developments. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2026, 547, 217119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lin, R.; Chen, J.; Qi, Y.; Lin, L. Magnesium Ion: A New Switch in Tumor Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaghegh, N.; Ahari, A.; Zehtabi, F.; Buttles, C.; Davani, S.; Hoang, H.; Tseng, K.; Zamanian, B.; Khosravi, S.; Daniali, A.; et al. Injectable hydrogels for personalized cancer immunotherapies. Acta Biomater. 2023, 172, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, S.; Yu, X.; Xu, C.; Wan, L.; Yao, F.; Witte, F.; Yang, S. Mechanism and application prospect of magnesium-based materials in cancer treatment. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 982–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R.; Wang, H.; Cai, W.; Ni, J.; Luthringer-Feyerabend, B.J.C.; Wang, W.; Peng, H.; Ji, W.; Yan, J.; Xia, J.; et al. Controlled release of hydrogen by implantation of magnesium induces P53-mediated tumor cells apoptosis. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 9, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Fang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Shen, J.; Fan, X. Metal ions and nanometallic materials in antitumor immunity: Function, application, and perspective. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, D.; Li, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chu, H.; Ye, J.; Liu, Y. Bioactive metallic nanoparticles for synergistic cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 1869–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Letter Re: Elevated serum magnesium levels prompt favorable outcomes in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockers. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 216, 115187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.D.S.; Santos, M.Q.D.; Makiyama, E.N.; Hoffmann, C.; Fock, R.A. The essential role of magnesium in immunity and gut health: Impacts of dietary magnesium restriction on peritoneal cells and intestinal microbiome. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2025, 88, 127604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Response to letter re: “Elevated serum magnesium levels prompt favorable outcomes in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockers”. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 216, 115249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Kawaguchi, T.; Funakoshi, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yasuda, Y.; Ando, Y. Efficacy of Magnesium Supplementation in Cancer Patients Developing Hypomagnesemia Due to Anti-EGFR Antibody: A Systematic Review. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2024, 4, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Setting | Effect on Mg2+ Levels | Actions | Pharmaceutical Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum salts chemotherapy | Renal reduction (hypomagnesemia); tremor, spams, arrythmia | Oral or i.v. supplementation; regular serum Mg2+ evaluation | Mg2+ Citrate or chloride; dose 200–400 mg/day i.v. |

| Anti-EGFR antibodies (cetuximab; panitumumab) | Increased Mg2+ renal excretion; asthenia, tremors | Monitoring every 2–4 weeks; supplement if Mg2+ <1.5 mg/dL | Mg2+ citrate or pidolate; dose 200–400 mg/day |

| Data | |||

| Proton pump inhibitors | Reduced Mg2+ intestinal absorption | Consider withdrawal or long- term supplementation | Mg2+ glycinate or malate; dose 150–200 mg/day |

| Immunotherapy | Normal or slightly elevated Mg2+ levels correlated to better outcomes | Keep Mg2+ within the physiological range of 1.7–2.3 mg/dL | Data are missing, possibly the same as for anti-EGFR antibodies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sambataro, D.; Scandurra, G.; Gebbia, V.; Greco, M.; Ciminna, A.; Valerio, M.R. Magnesium and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Narrative Practical Review. Nutrients 2026, 18, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010121

Sambataro D, Scandurra G, Gebbia V, Greco M, Ciminna A, Valerio MR. Magnesium and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Narrative Practical Review. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleSambataro, Daniela, Giuseppa Scandurra, Vittorio Gebbia, Martina Greco, Alessio Ciminna, and Maria Rosaria Valerio. 2026. "Magnesium and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Narrative Practical Review" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010121

APA StyleSambataro, D., Scandurra, G., Gebbia, V., Greco, M., Ciminna, A., & Valerio, M. R. (2026). Magnesium and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Narrative Practical Review. Nutrients, 18(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010121