Does Previous Anaphylaxis Determine Differences Between Patients Undergoing Oral Food Challenges to Cow’s Milk and Hen’s Egg?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Specific IgE Testing

2.3. Oral Food Challenges

2.4. Statistical Methodology

3. Results

3.1. General Information and Patient Demographics

3.2. Comparison Between Patient Groups by History of Anaphylaxis to the Challenged Food

3.3. Factors Influencing OFC Outcome in Studied Groups

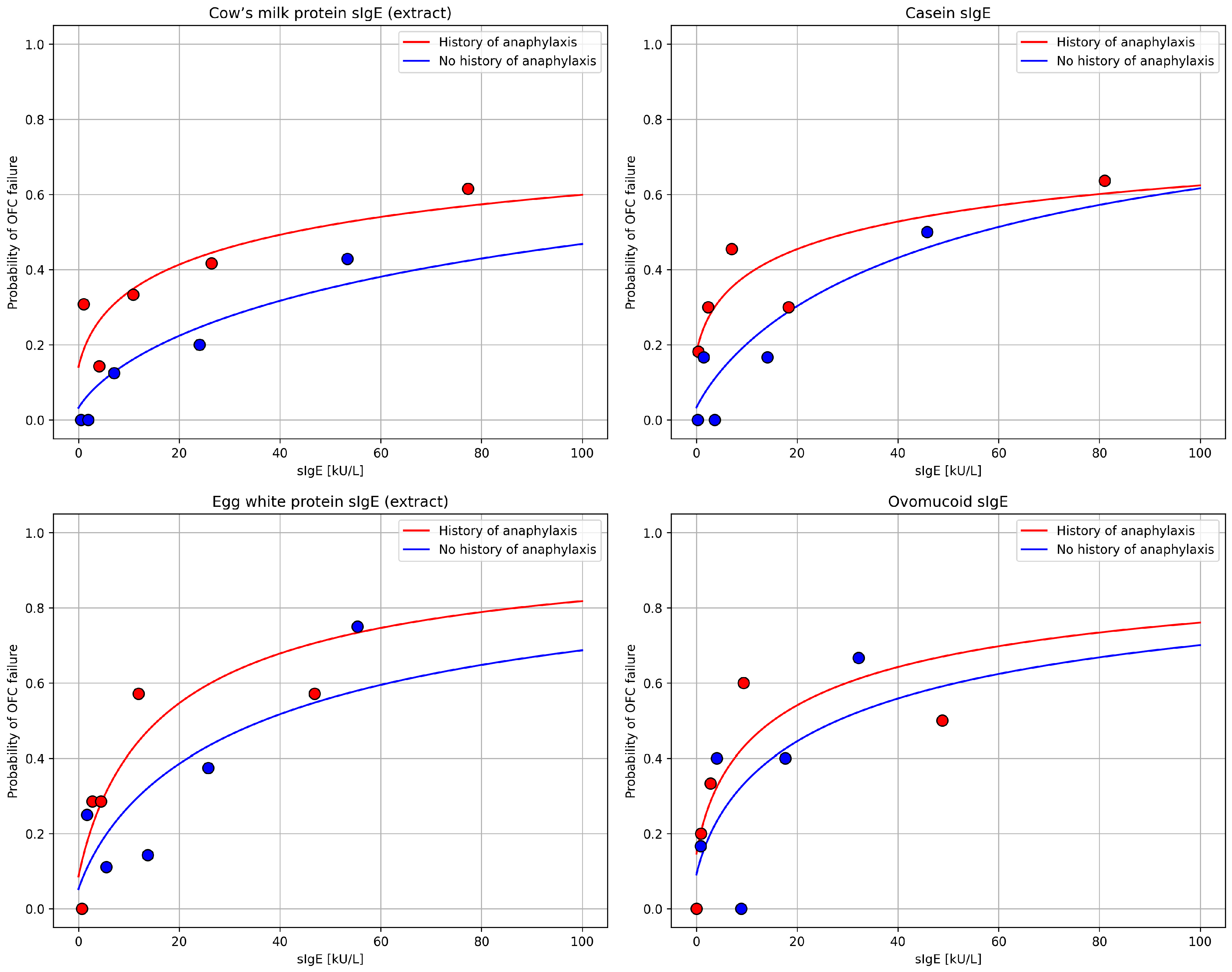

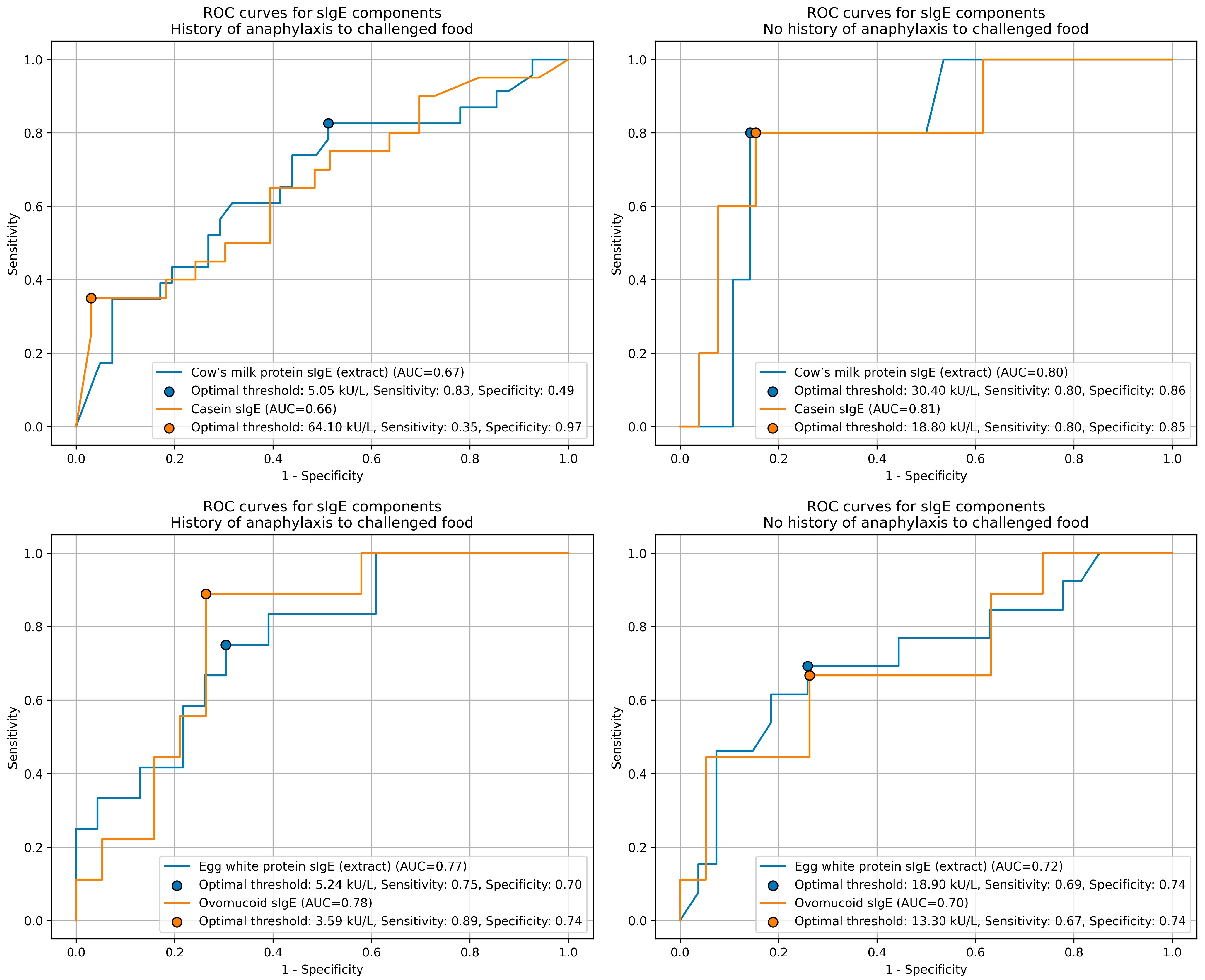

3.4. Specific IgE Concentration as a Predictor of OFC Outcome in Studied Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. General Information and Patient Demographics

4.2. Comparison Between Patient Groups by History of Anaphylaxis to the Challenged Food and Factors Influencing OFC Outcome in Studied Groups

4.3. Specific IgE Concentration as a Predictor of OFC Outcome in Studied Groups

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- A prior history of anaphylaxis might not increase the risk of severe reactions during supervised oral food challenges but is associated with higher allergen sensitivity and lower reactive doses.

- Predictors of oral food challenge failure differ by anaphylaxis history: atopic dermatitis is more relevant in children without prior anaphylaxis, while asthma in those with previous systemic reactions.

- Casein-specific IgE concentration is the most accurate serological predictor of cow’s milk challenge outcome in children without a history of anaphylaxis.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FA | food allergy |

| EAACI | European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology |

| CMP | cow’s milk protein |

| HEWP | hen’s egg white protein |

| sIgE | specific IgE |

| CRD | component-resolved diagnostics |

| BAT | basophil activation test |

| MAT | mast cell activation test |

| EDN | eosinophil-derived neurotoxin |

| OFC | oral food challenge |

| OIT | oral immunotherapy |

| FPIES | food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| AD | atopic dermatitis |

References

- Arens, A.; Lange, L.; Stamos, K. Epidemiology of Food Allergy. Allergo J. Int. 2025, 34, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolidoro, G.C.I.; Amera, Y.T.; Ali, M.M.; Nyassi, S.; Lisik, D.; Ioannidou, A.; Rovner, G.; Khaleva, E.; Venter, C.; van Ree, R.; et al. Frequency of Food Allergy in Europe: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 78, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, V.; Abrams, E.M.; Adlou, B.; Akdis, C.; Akdis, M.; Brough, H.A.; Chan, S.; Chatchatee, P.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; Cocco, R.R.; et al. Food Allergy across the Globe. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elghoudi, A.; Narchi, H. Food Allergy in Children-the Current Status and the Way Forward. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicherer, S.H.; Sampson, H.A. Food Allergy: A Review and Update on Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.A.; Clausen, M.; Knulst, A.C.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Barreales, L.; Bieli, C.; Dubakiene, R.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz, M.; et al. Prevalence of Food Sensitization and Food Allergy in Children Across Europe. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 2736–2746.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Allen, K.J.; Suaini, N.H.A.; McWilliam, V.; Peters, R.L.; Koplin, J.J. The Global Incidence and Prevalence of Anaphylaxis in Children in the General Population: A Systematic Review. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 74, 1063–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.J.; Campbell, D.E.; Motosue, M.S.; Campbell, R.L. Global Trends in Anaphylaxis Epidemiology and Clinical Implications. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueter, K.; Moseley, N.; Ta, B.; Bear, N.; Borland, M.L.; Prescott, S.L. Increasing Emergency Department Visits for Anaphylaxis in Very Early Childhood: A Canary in the Coal Mine. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2023, 112, 2182–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.B.; Arroyo, A.C.; Faridi, M.K.; Rudders, S.A.; Camargo, C.A. Trends in US Hospitalizations for Anaphylaxis Among Infants and Toddlers: 2006 to 2015. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 168–174.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraro, A.; Worm, M.; Alviani, C.; Cardona, V.; DunnGalvin, A.; Garvey, L.H.; Riggioni, C.; de Silva, D.; Angier, E.; Arasi, S.; et al. EAACI Guidelines: Anaphylaxis (2021 Update). Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażowski, Ł.; Kurzawa, R.; Majak, P. Food-Induced Anaphylaxis in Children—State of Art. Pediatr. Med. Rodz. 2021, 17, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, L.K.; Demoly, P. Anaphylaxis in Children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, Â.; Santos, N.; Faria, E.; Pereira, A.M.; Gomes, E.; Câmara, R.; Rodrigues-Alves, R.; Borrego, L.M.; Carrapatoso, I.; Carneiro-Leão, L.; et al. Anaphylaxis in Children and Adolescents: The Portuguese Anaphylaxis Registry. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoianova, S.; Sharma, V.; Boyle, R.J. Fatal Food Anaphylaxis in Children: A Statutory Review in England. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2025, 55, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül Emeksiz, Z.; Ertuğrul, A.; Uygun, S.D.; Özmen, S. Evaluation of Emotional, Behavioral, and Clinical Characteristics of Children Aged 1–5 with a History of Food-Related Anaphylaxis. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2023, 64, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baseggio Conrado, A.; Patel, N.; Turner, P.J. Global Patterns in Anaphylaxis Due to Specific Foods: A Systematic Review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1515–1525.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dölle-Bierke, S.; Höfer, V.; Francuzik, W.; Näher, A.F.; Bilo, M.B.; Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Lopes de Oliveira, L.C.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; García, B.E.; Hartmann, K.; et al. Food-Induced Anaphylaxis: Data from the European Anaphylaxis Registry. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 2069–2079.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouessel, G.; Jean-Bart, C.; Deschildre, A.; Van der Brempt, X.; Tanno, L.K.; Beaumont, P.; Dumond, P.; Sabouraud-Leclerc, D.; Beaudouin, E.; Ramdane, N.; et al. Food-Induced Anaphylaxis in Infancy Compared to Preschool Age: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2020, 50, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wen, J.; Zhang, H.; Zou, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, C. Clinical Characteristics of Anaphylaxis in Children Aged 0–16 Years in Xi’an, China. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 184, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Dölle-Bierke, S.; Jedynak-Wąsowicz, U.; Sabouraud-Leclerc, D.; Köhli, A.; Lange, L.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Hourihane, J.; Nemat, K.; Scherer Hofmeier, K.; et al. Cow’s Milk and Hen’s Egg Anaphylaxis: A Comprehensive Data Analysis from the European Anaphylaxis Registry. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2023, 13, e12228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klim, L.; Michalik, M.; Figura, N.; Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Jedynak-Wąsowicz, U. Food-Induced Anaphylaxis in Children Less than 2 Years of Age. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2025, 42, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novembre, E.; Gelsomino, M.; Liotti, L.; Barni, S.; Mori, F.; Giovannini, M.; Mastrorilli, C.; Pecoraro, L.; Saretta, F.; Castagnoli, R.; et al. Fatal Food Anaphylaxis in Adults and Children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barni, S.; Liccioli, G.; Sarti, L.; Giovannini, M.; Novembre, E.; Mori, F. Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-Mediated Food Allergy in Children: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management. Medicina 2020, 56, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggioni, C.; Ricci, C.; Moya, B.; Wong, D.; van Goor, E.; Bartha, I.; Buyuktiryaki, B.; Giovannini, M.; Jayasinghe, S.; Jaumdally, H.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses on the Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests for IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 79, 324–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafarotti, A.; Giovannini, M.; Begìn, P.; Brough, H.A.; Arasi, S. Management of IgE-Mediated Food Allergy in the 21st Century. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyziak-Mędrzycka, I.; Majsiak, E.; Gromek, W.; Kozłowska, D.; Swadźba, J.; Beata, B.J.; Kurzawa, R.; Cukrowska, B. The Sensitization Profile for Selected Food Allergens in Polish Children Assessed with the Use of a Precision Allergy Molecular Diagnostic Technique. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popielarz, M.; Krogulska, A. The Importance of Component-Resolved Diagnostics in IgE-Mediated Cow’s Milk Allergy. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2021, 49, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.W.; Sultana, R.; Lee, M.P.; Tan, L.L.; Goh, A.; Goh, S.H.; Loh, W. Diagnostic Accuracy of Skin Prick Test, Food-Specific IgE and Component Testing for IgE-Mediated Peanut, Egg, Milk and Wheat Allergy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2025, 55, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégin, P.; Waserman, S.; Protudjer, J.L.P.; Jeimy, S.; Watson, W. Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-Mediated Food Allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ, Ş.İ.K.; Öztürk, F.; Sancak, R.; Yildiran, A. The Role of Basophil Activation Test in the Diagnosis of Pediatric Egg Allergy in Turkey: A Comparison of Clinical and Laboratory Findings with Real-Life Data. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2025, 53, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, I.; Boyd, H.; Foong, R.X.; Krawiec, M.; Marques-Mejias, A.; Marshall, H.F.; Radulovic, S.; Harrison, F.; Antoneria, G.; Jama, Z.; et al. The Basophil Activation Test Is the Most Accurate Test in Predicting Allergic Reactions to Baked and Fresh Cow’s Milk During Oral Food Challenges. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 80, 2861–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licari, A.; D’Auria, E.; De Amici, M.; Castagnoli, R.; Sacchi, L.; Testa, G.; Marseglia, G.L. The Role of Basophil Activation Test and Component-Resolved Diagnostics in the Workup of Egg Allergy in Children at Low Risk for Severe Allergic Reactions: A Real-Life Study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 34, e14012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foong, R.X.; Santos, A.F. Biomarkers of Diagnosis and Resolution of Food Allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, R.L. A Diagnostic Approach to IgE-Mediated Food Allergy: A Practical Algorithm. J. Food Allergy 2024, 6, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, H.; Santos, A.F. Novel Diagnostics in Food Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 155, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzych-Fałta, E.; Białek, S.; Sybilski, A.J.; Tylewicz, A.; Samoliński, B.; Wojas, O. Differential Diagnostics of Food Allergy as Based on Provocation Tests and Laboratory Diagnostic Assays. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2023, 40, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahbah, W.A.; Abo Hola, A.S.; Bedair, H.M.; Taha, E.T.; El Zefzaf, H.M.S. Serum Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin: A New Promising Biomarker for Cow’s Milk Allergy Diagnosis. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 96, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, H.A.; Gerth Van Wijk, R.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Sicherer, S.; Teuber, S.S.; Burks, A.W.; Dubois, A.E.J.; Beyer, K.; Eigenmann, P.A.; Spergel, J.M.; et al. Standardizing Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Oral Food Challenges: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology-European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology PRACTALL Consensus Report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 1260–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, H.A.; Arasi, S.; Bahnson, H.T.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Beyer, K.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Bird, J.A.; Blumchen, K.; Davis, C.; Ebisawa, M.; et al. AAAAI–EAACI PRACTALL: Standardizing Oral Food Challenges—2024 Update. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebioğlu, E.; Akarsu, A.; Şahiner, Ü.M. Ige-Mediated Food Allergy throughout Life. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvani, M.; Bianchi, A.; Reginelli, C.; Peresso, M.; Testa, A. Oral Food Challenge. Medicina 2019, 55, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, E.; Soller, L.; Abrams, E.M.; Protudjer, J.L.P.; Mill, C.; Chan, E.S. Oral Food Challenge Implementation: The First Mixed-Methods Study Exploring Barriers and Solutions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 149–156.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, F.; Miyaji, Y.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Shimada, M.; Kiguchi, T.; Hirai, S.; Kram, Y.E.; Takada, K.; Noguchi, K.; Inuzuka, Y.; et al. Safer Oral Immunotherapy with Very Low-Dose Introduction for Pediatric Hen’s Egg Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 2025, 4, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ahn, K.; Kim, J. Practical Issues of Oral Immunotherapy for Egg or Milk Allergy. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2024, 67, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund, S.K.; Sampath, V.; Zhou, X.; Thai, B.; Desai, K.; Nadeau, K.C. Scientific Developments in Understanding Food Allergy Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1572283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, N.; Minoura, T.; Kitaoka, S.; Ebisawa, M. A Three-Level Stepwise Oral Food Challenge for Egg, Milk, and Wheat Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 658–660.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.J.; Patel, N.; Campbell, D.E.; Sampson, H.A.; Maeda, M.; Katsunuma, T.; Westerhout, J.; Blom, W.M.; Baumert, J.L.; Houben, G.F.; et al. Reproducibility of Food Challenge to Cow’s Milk: Systematic Review with Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 150, 1135–1143.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Fujita, M.; Inuo, C. Comparative Safety of Baked Egg, Egg Yolk, and Egg White in Young Children with Egg Allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J.E.M.; Lanser, B.J.; Bird, J.A.; Nowak-Węgrzyn, A. Baked Milk and Baked Egg Survey: A Work Group Report of the AAAAI Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 2335–2344.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthai, J.; Sathiasekharan, M.; Poddar, U.; Sibal, A.; Srivastava, A.; Waikar, Y.; Malik, R. Guidelines on Diagnosis and Management of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy. Indian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; Pediatric Gastroenterology Chapter of Indian Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines on Diagnosis and Management of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tosca, M.A.; Naso, M.; Trincianti, C.; Schiavetti, I.; Ciprandi, G. Reaction Severity to Oral Food Challenge to Milk Is Unpredictable: A Caveat for Clinical Practice. Acta Biomed. 2024, 95, e2024018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Moitra, S.; Saha, N.C.; Biswas, H.; Podder, S. Assessment of Egg and Milk Allergies among Indians by Revalidating a Food Allergy Predictive Model. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ünsal, H.; Gökçe, Ö.B.G.; Ocak, M.; Akarsu, A.; Şahiner, Ü.M.; Soyer, Ö.; Şekerel, B.E. Oral Food Challenge in IgE Mediated Food Allergy in Eastern Mediterranean Children. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2021, 49, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itazawa, T.; Adachi, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Miura, K.; Uehara, Y.; Kameda, M.; Kitamura, T.; Kuzume, K.; Tezuka, J.; Ito, K.; et al. The Severity of Reaction after Food Challenges Depends on the Indication: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.A.; Leonard, S.; Groetch, M.; Assa’ad, A.; Cianferoni, A.; Clark, A.; Crain, M.; Fausnight, T.; Fleischer, D.; Green, T.; et al. Conducting an Oral Food Challenge: An Update to the 2009 Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee Work Group Report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 75–90.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J.E.M.; Bird, J.A. Oral Food Challenges: Special Considerations. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebisawa, M.; Ito, K.; Fujisawa, T.; Aihara, Y.; Ito, S.; Imai, T.; Ohshima, Y.; Ohya, Y.; Kaneko, H.; Kondo, Y.; et al. Japanese Guidelines for Food Allergy 2020. Allergol. Int. 2020, 69, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Okafuji, I.; Kihara, T.; Kawanami, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Kotani, S.; Kamoi, Y.; Okutani, T. Safety of Low-Dose Oral Food Challenges for Hen’s Eggs, Cow’s Milk, and Wheat: Report from a General Hospital without Allergy Specialists in Japan. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2023, 69, E16–E24. [Google Scholar]

- Assa’ad, A.H. Oral Food Challenges. J. Food Allergy 2020, 2, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, M.R.; Araújo, L.M.L.; Filho, N.A.R. Oral Food Challenge in Children with Contact Urticaria in Reaction to Cow’s Milk. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2023, 51, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiwe, J. Using Oral Food Challenges to Provide Clarity and Confidence When Diagnosing Food Allergies. J. Food Allergy 2021, 3, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, M.; Yanagida, N.; Sato, S.; Nagakura, K.-i.; Takahashi, K.; Ogura, K.; Ebisawa, M. Risk Factors for Failing a Repeat Oral Food Challenge in Preschool Children with Hen’s Egg Allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, e13895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.G.; Fernando, S.L.; Nickolls, C.; Li, J. Oral Food Challenge Outcomes in Children and Adolescents in a Tertiary Centre: A 5-Year Experience. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2023, 59, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagida, N.; Sato, S.; Asaumi, T.; Ogura, K.; Ebisawa, M. Risk Factors for Severe Reactions during Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Food Challenges. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 172, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Jeong, K.; Park, M.; Roh, Y.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.D.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Sohn, M.H.; et al. Predicting the Outcome of Pediatric Oral Food Challenges for Determining Tolerance Development. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2024, 16, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutlas, N.; Stallings, A.; Hall, G.; Zhou, C.; Kim-Chang, J.; Mousallem, T. Pediatric Oral Food Challenges in the Outpatient Setting: A Single-Center Experience. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 2024, 3, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klim, L.; Michalik, M.; Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Jedynak-Wąsowicz, U. Asthma and Multi-Food Allergy Are Risk Factors for Oral Food Challenge Failure-A Single-Center Experience. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Assa’ad, A.H.; Bahna, S.L.; Bock, S.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Teuber, S.S. Work Group Report: Oral Food Challenge Testing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, S365–S383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.A.; Caubet, J.C.; Kim, J.S.; Groetch, M.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Baked Milk- and Egg-Containing Diet in the Management of Milk and Egg Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2015, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, H.A. Anaphylaxis and Emergency Treatment. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, K.; Feeney, M.; Yerlett, N.; Meyer, R. Nutritional Management of Children with Food Allergies. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2022, 9, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, G.; Carciofi, A.; Borgiani, F.; Cappelletti, D.; Correani, A.; Monachesi, C.; Gatti, S.; Lionetti, M.E. Are We Meeting the Needs? A Systematic Review of Nutritional Gaps and Growth Outcomes in Children with Multiple Food Allergies. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotchetkoff, E.C.d.A.; de Oliveira, L.C.L.; Sarni, R.O.S. Elimination Diet in Food Allergy: Friend or Foe? J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, S65–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.A.; Crain, M.; Varshney, P. Food Allergen Panel Testing Often Results in Misdiagnosis of Food Allergy. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 97–100.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, C.P. A Review of Food Allergy Panels and Their Consequences. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 131, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herber, C.; Bogler, L.; Subramanian, S.V.; Vollmer, S. Association Between Milk Consumption and Child Growth for Children Aged 6–59 Months. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.A.; Zhao, Z.; Bader-Larsen, K.S.; Magkos, F. Egg Consumption and Growth in Children: A Meta-Analysis of Interventional Trials. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1278753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz, M.; Alam, M.A.; Das, S.; Fahim, S.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Petri, W.A.; Ashorn, P.; Ashorn, U.; Ahmed, T. Daily Supplementation with Egg, Cow Milk, and Multiple Micronutrients Increases Linear Growth of Young Children with Short Stature. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corica, D.; Aversa, T.; Caminiti, L.; Lombardo, F.; Wasniewska, M.; Pajno, G.B. Nutrition and Avoidance Diets in Children with Food Allergy. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.C.D.C.; Speridião, P.D.G.L.; Sanudo, A.; Morais, M.B. Feeding Difficulties in Children Fed a Cows’ Milk Elimination Diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziechciarz, P.; Stróżyk, A.; Horvath, A.; Cudowska, B.; Jedynak-Wąsowicz, U.; Mól, N.; Jarocka-Cyrta, E.; Zawadzka-Krajewska, A.; Krauze, A. Nutritional Status and Feeding Difficulties in Children up to 2 Years of Age with Cow’s Milk Allergy. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 79, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagi, Y.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Ogita, H.; Kiguchi, T.; Inuzuka, Y.; Toyokuni, K.; Nishimura, K.; Irahara, M.; Ishikawa, F.; Sato, M.; et al. Avoidance of Hen’s Egg Based on IgE Levels Should Be Avoided for Children with Hen’s Egg Allergy. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 8, 583224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, P.M.; Cassin, A.M.; Durban, R.; Upton, J.E.M. Effects of Food Processing on Allergenicity. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2025, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Bloom, K.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Shreffler, W.G.; Noone, S.; Wanich, N.; Sampson, H.A. Tolerance to Extensively Heated Milk in Children with Cow’s Milk Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 342–347.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzelle, V.; Juchet, A.; Martin-Blondel, A.; Michelet, M.; Chabbert-Broue, A.; Didier, A. Benefits of Baked Milk Oral Immunotherapy in French Children with Cow’s Milk Allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Nowak-Węgrzyn, A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Noone, S.; Moshier, E.L.; Sampson, H.A. Dietary Baked Milk Accelerates the Resolution of Cow’s Milk Allergy in Children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 125–131.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.A.; Sampson, H.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Noone, S.; Moshier, E.L.; Godbold, J.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Dietary Baked Egg Accelerates Resolution of Egg Allergy in Children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 473–480.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, A.; Toschi Vespasiani, G.; Ricci, G.; Miniaci, A.; Di Palmo, E.; Pession, A. Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy as a Model of Food Allergies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantulga, P.; Lee, J.; Jeong, K.; Jeon, S.A.; Lee, S. Variation in the Allergenicity of Scrambled, Boiled, Short-Baked and Long-Baked Egg White Proteins. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Meyer, R.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Salvatore, S.; Venter, C.; Vieira, M.C. The Remaining Challenge to Diagnose and Manage Cow’s Milk Allergy: An Opinion Paper to Daily Clinical Practice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, J.E.M.; Wong, D.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Baked Milk and Egg Diets Revisited. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 132, 328–336.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyuktiryaki, B.; Soyer, O.; Bingol, G.; Can, C.; Nacaroglu, H.T.; Bingol, A.; Arik Yilmaz, E.; Aydogan, M.; Sackesen, C. Milk Ladder: Who? When? How? Where? With the Lowest Risk of Reaction. Front. Allergy 2024, 5, 1516774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, C.; Meyer, R.; Groetch, M.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Mennini, M.; Pawankar, R.; Kamenwa, R.; Assa’ad, A.; Amara, S.; Fiocchi, A.; et al. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines Update—XVI—Nutritional Management of Cow’s Milk Allergy. World Allergy Organ. J. 2024, 17, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, C.R.; Vázquez, D.; Machinena-Spera, A.; Folqué Jiménez, d.M.; Lozano-Blasco, J.; Feijoo, R.J.; Sánchez, O.D.; Gibert, M.P.; Costa, M.D.; Alvaro-Lozano, M. Tolerance to Cooked Egg in Infants with Risk Factors for Egg Allergy After Early Introduction of Baked Egg. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2025, 53, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Boven, F.E.; Arends, N.J.T.; Sprikkelman, A.B.; Emons, J.A.M.; Hendriks, A.I.; van Splunter, M.; Schreurs, M.W.J.; Terlouw, S.; Gerth van Wijk, R.; Wichers, H.J.; et al. Tolerance Induction in Cow’s Milk Allergic Children by Heated Cow’s Milk Protein: The IAGE Follow-Up Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballini, G.; Gavagni, C.; Guidotti, C.; Ciolini, G.; Liccioli, G.; Giovannini, M.; Sarti, L.; Ciofi, D.; Novembre, E.; Mori, F.; et al. Frequency of Positive Oral Food Challenges and Their Outcomes in the Allergy Unit of a Tertiary-Care Pediatric Hospital. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2021, 49, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, M.; Kido, J.; Yoshida, T.; Nishi, N.; Shimomura, S.; Hirai, N.; Mizukami, T.; Yanai, M.; Nakamura, K. The Efficacy and Safety of Stepwise Oral Food Challenge in Children with Hen’s Egg Allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeksiz, Z.S.; Ertugrul, A.; Ozmen, S.; Cavkaytar, O.; Ercan, N.; Bostancl, I.B. Is Oral Food Challenge as Safe Enough as It Seems? J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmab065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uekert, S.J.; Akan, G.; Evans, M.D.; Li, Z.; Roberg, K.; Tisler, C.; DaSilva, D.; Anderson, E.; Gangnon, R.; Allen, D.B.; et al. Sex-Related Differences in Immune Development and the Expression of Atopy in Early Childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Imai, T.; Okada, Y.; Maeda, M.; Kamiya, T. Severe Anaphylaxis Requiring Continuous Adrenaline Infusion during Oral Food Challenge: A Case Series. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 133, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vininski, M.S.; Rajput, S.; Hobbs, N.J.; Dolence, J.J. Understanding Sex Differences in the Allergic Immune Response to Food. AIMS Allergy Immunol. 2022, 6, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffler, J.; Stumbles, P.A.; Strickland, D.H. Immunological Processes Driving IgE Sensitisation and Disease Development in Males and Females. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindher, S.; Long, A.J.; Purington, N.; Chollet, M.; Slatkin, S.; Andorf, S.; Tupa, D.; Kumar, D.; Woch, M.A.; O’Laughlin, K.L.; et al. Analysis of a Large Standardized Food Challenge Data Set to Determine Predictors of Positive Outcome Across Multiple Allergens. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagmur, I.T.; Celik, I.K.; Topal, O.Y.; Toyran, M.; Civelek, E.; Misirlioglu, E.D. Development of Anaphylaxis upon Oral Food Challenge and Drug Provocation Tests in Pediatric Patients. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2023, 44, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilante, B.P.; Castro, A.P.B.M.; Yonamine, G.H.; de Barros Dorna, M.; Barp, M.F.; Martins, T.P.d.R.; Pastorino, A.C. IgE-Mediated Cow’s Milk Allergy in Brazilian Children: Outcomes of Oral Food Challenge. World Allergy Organ. J. 2023, 16, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.A.; Nurmatov, U.; DunnGalvin, A.; Reese, I.; Vieira, M.C.; Rommel, N.; Dupont, C.; Venter, C.; Cianferoni, A.; Walsh, J.; et al. Feeding Difficulties in Children with Food Allergies: An EAACI Task Force Report. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluzzi, R.L.; Riccardi, C.; Arasi, S.; Piscitelli, A.L.; Calandrelli, V.; Dahdah, L.; Fierro, V.; Mennini, M.; Fiocchi, A. Cow’s Milk and Egg Protein Threshold Dose Distributions in Children Tolerant to Beef, Baked Milk, and Baked Egg. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 3052–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonkof, J.R.; Mikhail, I.J.; Prince, B.T.; Stukus, D. Delayed and Severe Reactions to Baked Egg and Baked Milk Challenges. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 283–289.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J.; Alvaro, M.; Nadeau, K. A Perspective on the Pediatric Death from Oral Food Challenge Reported from the Allergy Vigilance Network. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 74, 1035–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.M.; Anvari, S.; Hauk, P.; Lio, P.; Nanda, A.; Sidbury, R.; Schneider, L. Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergy: Best Practices and Knowledge Gaps—A Work Group Report from the AAAAI Allergic Skin Diseases Committee and Leadership Institute Project. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, E.M.; Becker, A.B. Oral Food Challenge Outcomes in a Pediatric Tertiary Care Center. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2017, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapostolou, N.; Xepapadaki, P.; Gregoriou, S.; Makris, M. Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergy: A Complex Interplay What We Know and What We Would Like to Learn. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trogen, B.; Verma, M.; Sicherer, S.H.; Cox, A. The Role of Food Allergy in Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol. Clin. 2024, 42, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui-Beckman, J.W.; Goleva, E.; Berdyshev, E.; Leung, D.Y.M. Endotypes of Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsukkaeo, S.; Suksawat, Y. Early-Life Risk Factors and Clinical Features of Food Allergy Among Thai Children. Int. J. Pediatr. 2024, 2024, 6767537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito-Abe, M.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Pak, K.; Iwamoto, S.; Sato, M.; Miyaji, Y.; Mezawa, H.; Nishizato, M.; Yang, L.; Kumasaka, N.; et al. How a Family History of Allergic Diseases Influences Food Allergy in Children: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, S.; Galletta, F.; Bencivenga, C.L.; Bettini, I.; Klain, A.; D’Addio, E.; Mori, F.; Licari, A.; Miraglia Del Giudice, M.; Indolfi, C. Food Allergy Risk: A Comprehensive Review of Maternal Interventions for Food Allergy Prevention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, N.; Protudjer, J.L.P.; Hsu, E.; Soller, L.; Chan, E.S.; Kim, H.; Jeimy, S. Canadian Parent Perceptions of Oral Food Challenges: A Qualitative Analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, e13698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, D.; Gujski, M.; Bojar, I.; Raciborski, F. Importance of Food Allergy and Food Intolerance in Allergic Multimorbidity. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purington, N.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; Long, A.; Sindher, S.; Andorf, S.; O’Laughlin, K.; Woch, M.A.; Scheiber, A.; Assa’Ad, A.; Pongracic, J.; et al. Eliciting Dose and Safety Outcomes from a Large Dataset of Standardized Multiple Food Challenges. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.; Alfaro, M.K.C.; Spergel, Z.C.; Dorris, S.L.; Spergel, J.M.; Capucilli, P. Differences in Oral Food Challenge Reaction Severity Based on Increasing Age in a Pediatric Population. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 127, 562–567.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emons, J.A.M.; Gerth van Wijk, R. Food Allergy and Asthma: Is There a Link? Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2018, 5, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foong, R.X.; du Toit, G.; Fox, A.T. Asthma, Food Allergy, and How They Relate to Each Other. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Xu, W.; Huang, H.; Hou, X.; Xiang, L. Anaphylaxis in Chinese Children: Different Clinical Profile Between Children with and without a History of Asthma/Recurrent Wheezing. J. Asthma Allergy 2022, 15, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dribin, T.E.; Michelson, K.A.; Zhang, Y.; Schnadower, D.; Neuman, M.I. Are Children with a History of Asthma More Likely to Have Severe Anaphylactic Reactions? A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. 2020, 220, 159–164.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunico, D.; Giannì, G.; Scavone, S.; Buono, E.V.; Caffarelli, C. The Relationship Between Asthma and Food Allergies in Children. Children 2024, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukus, D.R.; Prince, B.T. Asthma and Food Allergy: A Nuanced Relationship. J. Food Allergy 2023, 5, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palmo, E.; Gallucci, M.; Cipriani, F.; Bertelli, L.; Giannetti, A.; Ricci, G. Asthma and Food Allergy: Which Risks? Medicina 2019, 55, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, R.; Cartledge, N.; Lazenby, S.; Tobias, A.; Chan, S.; Fox, A.T.; Santos, A.F. Specific IgE as the Best Predictor of the Outcome of Challenges to Baked Milk and Baked Egg. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1459–1461.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, N.; Sato, S.; Ebisawa, M. Relationship Between Eliciting Doses and the Severity of Allergic Reactions to Food. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 23, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, N.; Sato, S.; Takahashi, K.; Nagakura, K.I.; Asaumi, T.; Ogura, K.; Ebisawa, M. Increasing Specific Immunoglobulin E Levels Correlate with the Risk of Anaphylaxis during an Oral Food Challenge. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 29, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hawi, Y.; Nagao, M.; Furuya, K.; Sato, Y.; Ito, S.; Hori, H.; Hirayama, M.; Fujisawa, T. Agreement between Predictive, Allergen-Specific IgE Values Assessed by ImmunoCAP and IMMULITE 2000 3gAllergyTM Assay Systems for Milk and Wheat Allergies. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2021, 13, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, Y.; Matsunami, K.; Kondo, M.; Matsukuma, E.; Imamura, A.; Kaneko, H. Oral Food Challenge Test Results of Patients with Food Allergy with Specific IgE Levels > 100 UA/mL. Biomed. Rep. 2024, 21, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Kido, J.; Ogata, M.; Watanabe, S.; Nishi, N.; Shimomura, S.; Hirai, N.; Tanaka, K.; Yanai, M.; Mizukami, T.; et al. Safety of Oral Food Challenges for Individuals with Low Levels of Cow’s Milk-Specific Immunoglobulin e Antibodies. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 186, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiwe, J. Oral Food Challenges in Infants and Toddlers. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2019, 39, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawryjołek, J.; Wycech, A.; Smyk, A.; Krogulska, A. Difficulties in Interpretation of Oral Food Challenge Results. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2021, 38, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashho, K.; Garber, M.; Yousef, E. Interpreting Serum-Specific IgE Panels: Key Insights for Pediatricians in Diagnosing Food Allergies in Children. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2025, 39, 922–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosca, M.A.; Schiavetti, I.; Olcese, R.; Trincianti, C.; Ciprandi, G. Molecular Allergy Diagnostics in Children with Cow’s Milk Allergy: Prediction of Oral Food Challenge Response in Clinical Practice. J. Immunol. Res. 2023, 2023, 1129449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, O.; Palosuo, K.; Mäkelä, M.J. Casein SIgE as the Most Accurate Predictor for Heated Milk Tolerance in Finnish Children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 36, e70152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayats-Vidal, R.; Valdesoiro-Navarrete, L.; García-González, M.; Asensio-De la Cruz, O.; Larramona-Carrera, H.; Bosque-García, M. Predictors of a Positive Oral Food Challenge to Cow’s Milk in Children Sensitized to Cow’s Milk. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2020, 48, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, K.W.; Goh, S.H.; Saffari, S.E.; Loh, W.; Sia, I.; Seah, S.; Goh, A. IgE-Mediated Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy in Singaporean Children. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 40, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, O.; Riggioni, C.; Poyatos, E.; Jiménez-Feijoo, R.M.; Piquer, M.; Machinena, A.; Folqué, M.; Ortiz de Landazuri, I.; Torradeflot, M.; Lozano, J.; et al. Biomarkers of Tolerance to Baked Milk in Cow’s Milk-Allergic Children at High Risk of Anaphylaxis. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2026, 36. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic, M.; Çilkol, L.; Taşkın, E. Evaluation of Some Predictive Parameters for Baked-Milk Tolerance in Children with Cow’s Milk Allergy. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2021, 49, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Catalán, J.; González-Arias, A.M.; Casas, A.V.; Camacho, G.D.R. Specific IgE Levels as an Outcome Predictor in Egg-Allergic Children. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2021, 49, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.S.; Santos, G.M.d.; Sangalho, I.; Rosa, S.; Pinto, P.L. Role of Serum-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Egg Allergy: A Comprehensive Study of Portuguese Pediatric Patients. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2024, 52, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, T.T.; Matsui, E.C.; Kay Conover-Walker, M.; Wood, R.A. The Relationship of Allergen-Specific IgE Levels and Oral Food Challenge Outcome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 114, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Colli, L.; Yu, J.; Lanoue, D.; Mir, A.; Cohen, C.G.; Toscano-Rivero, D.; Sacksner, J.; Mazer, B.; Mccusker, C.; Ke, D.; et al. Predicting Cow’s Milk Challenge Outcomes in Children: Multivariate Analysis of Clinical Predictors. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 186, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesa, J.M.; Dobrzynska, A.; Baños-Álvarez, E.; Isabel-Gómez, R.; Blasco-Amaro, J.A. ImmunoCAP ISAC in Food Allergy Diagnosis: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaydin, N.C.; Severcan, E.U.; Akarcan, S.E.; Bal, C.M.; Gulen, F.; Tanac, R.; Demir, E. Effects of Cow’s Milk Components, Goat’s Milk and Sheep’s Milk Sensitivities on Clinical Findings and Tolerance Development in Cow’s Milk Allergy. SiSli Etfal Hastan. Tip Bul. Med. Bull. Sisli Hosp. 2021, 55, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, C.; Muñoz Archidona, C.; Fernández Prudencio, B.; Gallagher, A.; Velasco Zuniga, R.; Trujillo Wurttele, J. Real-Life Use of Component-Specific IgE in IgE-Mediated Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy in a Spanish Paediatric Allergy Centre. Antibodies 2023, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodi, G.; Di Filippo, P.; Di Pillo, S.; Chiarelli, F.; Attanasi, M. Total Serum IgE Levels as Predictor of the Acquisition of Tolerance in Children with Food Allergy: Findings from a Pilot Study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 1013807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malucelli, M.; Farias, R.; Mello, R.G.; Prando, C. Biomarkers Associated with Persistence and Severity of IgE-Mediated Food Allergies: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. 2023, 99, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 192 * |

| Median age [IQR], (years) | 4.75 [3.32–6.82] |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 127 (66.1%) |

| Female | 65 (33.9%) |

| Allergen challenged in the OFC, n (%) | |

| Cow’s milk protein (CMP) | 106 (55.2%) |

| Hen’s egg white protein (HEWP) | 86 (44.8%) |

| Median time from food consumption to reaction occurrence [IQR], (minutes) | 90.0 [60.0–120.0] |

| Accompanying atopic diseases | |

| Multi-food allergy | 147 (76.6%) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 120 (62.5%) |

| Asthma | 97 (50.5%) |

| Family history of atopy | 85 (44.3%) |

| History of anaphylaxis to the challenged food # | 110 (57.3%) |

| Grade 2 | 39 (35.5%) |

| Grade 3 | 34 (30.9%) |

| Grade 4 | 35 (31.8%) |

| Grade 5 | 2 (1.8%) |

| Feature | History of Anaphylaxis to the Challenged Food * (n = 110) | No History of Anaphylaxis to the Challenged Food * (n = 82) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of failed OFCs | 39 (35.5%) | 23 (28.1%) | 0.46 |

| Median age [IQR], (years) | 4.57 [2.96–6.87] | 5.04 [3.70–6.78] | 0.45 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 69 (62.7%) | 58 (70.7%) | 0.25 |

| Female | 41 (37.3%) | 24 (29.3%) | |

| Allergen challenged in the OFC, n (%) | |||

| Cow’s milk protein (CMP) | 70 (63.6%) | 36 (43.9%) | 0.01 |

| Hen’s egg white protein (HEWP) | 40 (36.4%) | 46 (50.1%) | |

| Median time from food consumption to reaction occurrence [IQR], (minutes) | 90.0 [65.0–150.0] | 90.0 [50.0–120.0] | 0.67 |

| Accompanying atopic diseases | |||

| Multi-food allergy | 81 (73.6%) | 66 (80.5%) | 0.27 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 62 (56.4%) | 58 (70.7%) | 0.04 |

| Asthma | 60 (54.6%) | 37 (45.1%) | 0.20 |

| Family history of atopy | 52 (47.3%) | 33 (40.2%) | 0.33 |

| N | CMP (g) | N | HEWP (g) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of anaphylaxis to the challenged food | 25 | 0.41 [0.13–1.09] | 14 | 0.44 [0.29–1.02] | 0.66 |

| No history of anaphylaxis to the challenged food | 7 | 0.54 [0.14–1.12] | 16 | 1.17 [0.51–2.34] | 0.15 |

| p value | 0.45 | 0.03 |

| Variable | History of Anaphylaxis (N = 106) | No History of Anaphylaxis (N = 80) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | |

| Asthma | 0.83 (−0.03, 1.69) | 0.05 | −0.50 (−1.61, 0.62) | 0.38 |

| Atopic dermatitis | −0.44 (−1.29, 0.42) | 0.32 | 1.80 (0.34, 3.26) | 0.02 |

| Family history of atopy | −0.14 (−0.97, 0.69) | 0.74 | −1.11 (−2.28, 0.06) | 0.06 |

| Multi-food allergy | 0.82 (−0.27, 1.91) | 0.14 | 1.59 (−0.10, 3.27) | 0.07 |

| CMP-Specific IgE [kU/L] | Casein-Specific IgE [kU/L] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Passed | N | Failed | p | N | Passed | N | Failed | p | |

| History of anaphylaxis to the challenged food | 41 | 6.19 [2.54–20.20] | 23 | 19.40 [6.71–58.10] | 0.03 | 33 | 4.99 [0.80–17.30] | 20 | 10.99 [4.37–91.00] | 0.05 |

| No history of anaphylaxis to the challenged food | 28 | 4.96 [1.25–21.55] | 5 | 30.43 [30.40–45.00] | 0.04 | 26 | 2.75 [0.53–8.90] | 5 | 30.95 [18.80–37.10] | 0.03 |

| p | 0.34 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.76 | ||||||

| HEWP-Specific IgE [kU/L] | Ovomucoid-Specific IgE [kU/L] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Passed | N | Failed | p | N | Passed | N | Failed | p | |

| History of anaphylaxis to the challenged food | 23 | 3.26 [1.21–6.69] | 12 | 11.20 [4.81–33.03] | 0.01 | 19 | 1.67 [0.01–3.62] | 9 | 10.30 [3.59–16.90] | 0.02 |

| No history of anaphylaxis to the challenged food | 27 | 7.72 [3.86–20.30] | 13 | 27.00 [11.30–39.00] | 0.03 | 19 | 7.35 [1.91–14.95] | 9 | 16.60 [5.16–24.20] | 0.09 |

| p | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.60 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Klim, L.; Michalik, M.; Wąsowicz, P.; Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Jedynak-Wąsowicz, U. Does Previous Anaphylaxis Determine Differences Between Patients Undergoing Oral Food Challenges to Cow’s Milk and Hen’s Egg? Nutrients 2026, 18, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020302

Klim L, Michalik M, Wąsowicz P, Cichocka-Jarosz E, Jedynak-Wąsowicz U. Does Previous Anaphylaxis Determine Differences Between Patients Undergoing Oral Food Challenges to Cow’s Milk and Hen’s Egg? Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020302

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlim, Liliana, Maria Michalik, Paweł Wąsowicz, Ewa Cichocka-Jarosz, and Urszula Jedynak-Wąsowicz. 2026. "Does Previous Anaphylaxis Determine Differences Between Patients Undergoing Oral Food Challenges to Cow’s Milk and Hen’s Egg?" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020302

APA StyleKlim, L., Michalik, M., Wąsowicz, P., Cichocka-Jarosz, E., & Jedynak-Wąsowicz, U. (2026). Does Previous Anaphylaxis Determine Differences Between Patients Undergoing Oral Food Challenges to Cow’s Milk and Hen’s Egg? Nutrients, 18(2), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020302