Obesity Phenotyping in Children and Adolescents: Next Steps Towards Precision Medicine in Pediatric Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Drivers of Pediatric Obesity

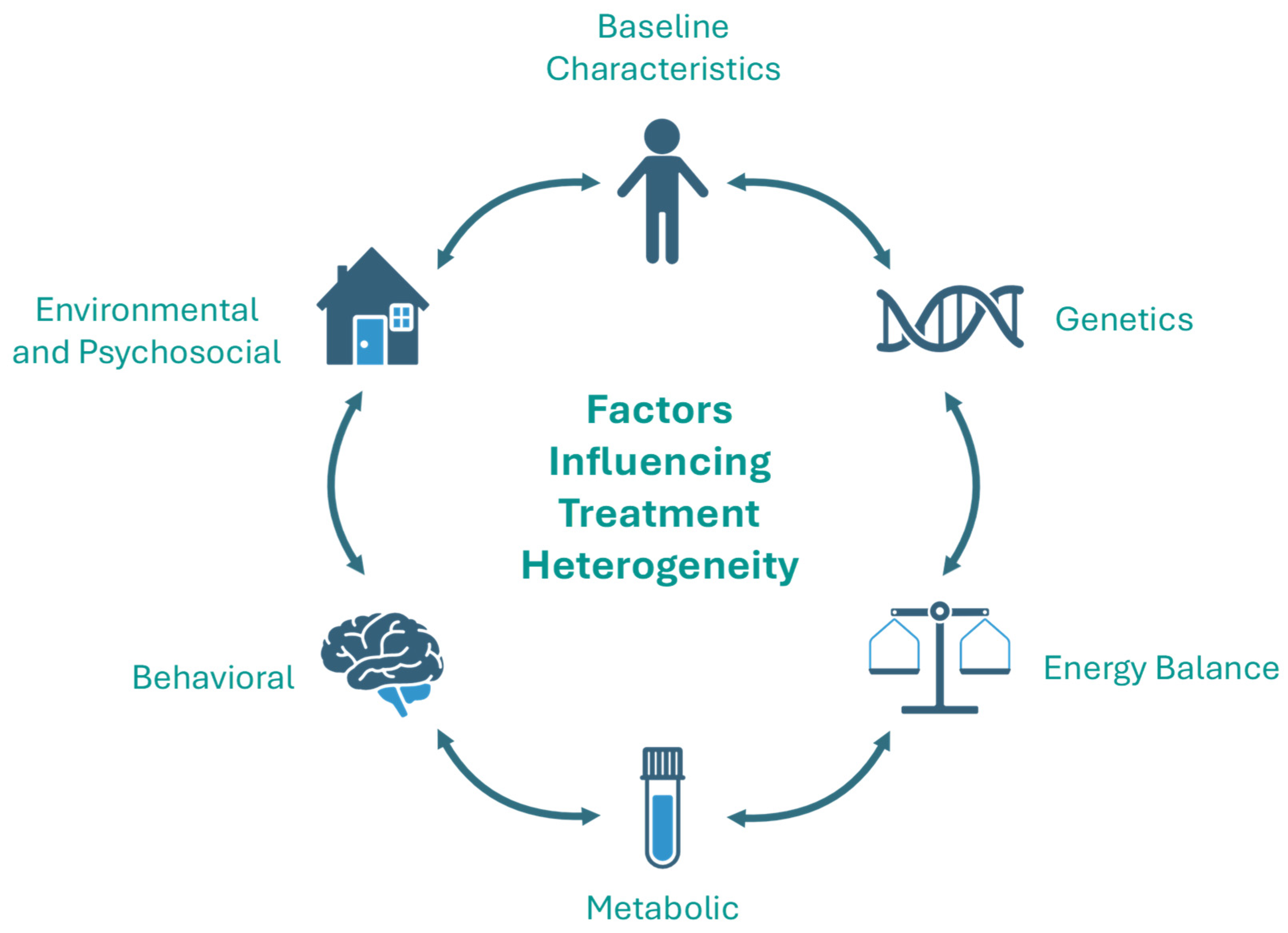

4. Heterogeneity in Treatment Response

5. Factors That Influence Heterogeneity in Treatment Response

5.1. Baseline Characteristics

5.2. Genetics

5.3. Energy Balance

5.4. Metabolic

5.5. Eating Behavior

5.6. Environmental and Psychosocial Factors

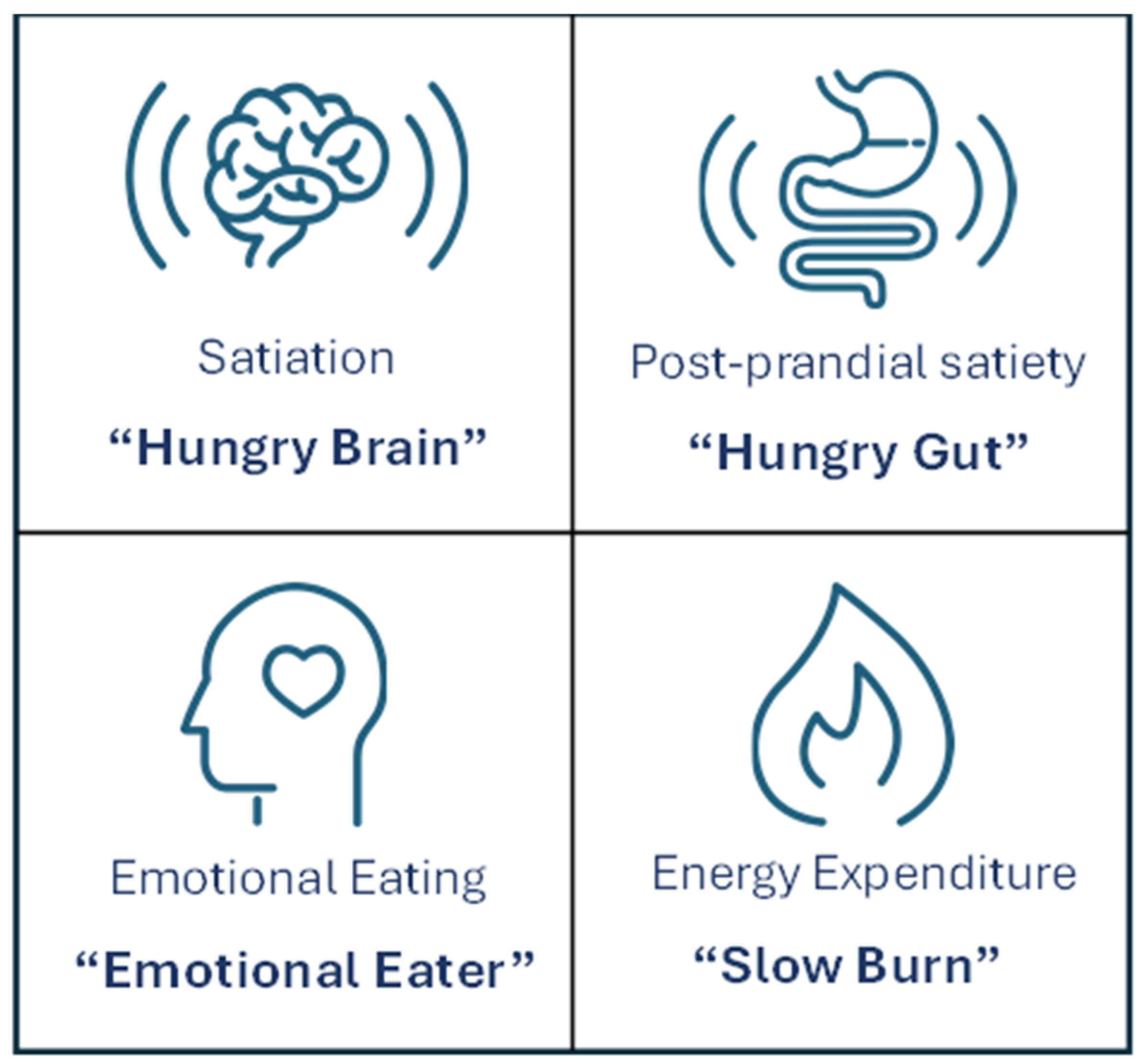

6. Obesity Phenotyping

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Adolescent BMI Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence of child and adolescent overweight and obesity, 1990-2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Ni, Y.; Yi, C.; Fang, Y.; Ning, Q.; Shen, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Global Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, T.S.; Arslanian, S.A. Obesity in Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twig, G.; Yaniv, G.; Levine, H.; Leiba, A.; Goldberger, N.; Derazne, E.; Ben-Ami Shor, D.; Tzur, D.; Afek, A.; Shamiss, A.; et al. Body-Mass Index in 2.3 Million Adolescents and Cardiovascular Death in Adulthood. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2430–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L.; Olsen, L.W.; Sorensen, T.I. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder, J.R.; Kaizer, A.M.; Jenkins, T.M.; Kelly, A.S.; Inge, T.H.; Shaibi, G.Q. Heterogeneity in Response to Treatment of Adolescents with Severe Obesity: The Need for Precision Obesity Medicine. Obesity 2019, 27, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenway, F.L. Physiological adaptations to weight loss and factors favouring weight regain. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, J.A.; Beech, B.M. Attrition in paediatric weight management: A review of the literature and new directions. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e273–e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomberg, E.M.; Ryder, J.R.; Brundage, R.C.; Straka, R.J.; Fox, C.K.; Gross, A.C.; Oberle, M.M.; Bramante, C.T.; Sibley, S.D.; Kelly, A.S. Precision medicine in adult and pediatric obesity: A clinical perspective. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 10, 2042018819863022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.S.; Marcus, M.D.; Yanovski, J.A.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Osganian, S.K. Working toward precision medicine approaches to treat severe obesity in adolescents: Report of an NIH workshop. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.S.; Del-Ponte, B.; Assuncao, M.C.F.; Santos, I.S. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and body fat during childhood and adolescence: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, M.; Lafontan, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Winzer, E.; Yumuk, V.; Farpour-Lambert, N. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review from 2013 to 2015 and a Comparison with Previous Studies. Obes. Facts 2017, 10, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.; Mander, A.P.; Jones, L.R.; Emmett, P.M.; Jebb, S.A. Energy-dense, low-fiber, high-fat dietary pattern is associated with increased fatness in childhood. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahumud, R.A.; Sahle, B.W.; Owusu-Addo, E.; Chen, W.; Morton, R.L.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Association of dietary intake, physical activity, and sedentary behaviours with overweight and obesity among 282,213 adolescents in 89 low and middle income to high-income countries. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 2404–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, N.; Viner, R.M. Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.J.F.; Yeo, G.S.H. The genetics of obesity: From discovery to biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.; El-Rabaa, G.; Freiha, M.; Kedzia, A.; Niechcial, E. Endocrine consequences of childhood obesity: A narrative review. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1584861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N. Causes, consequences, and treatment of metabolically unhealthy fat distribution. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginean, C.O.; Melit, L.E.; Hutanu, A.; Ghiga, D.V.; Sasaran, M.O. The adipokines and inflammatory status in the era of pediatric obesity. Cytokine 2020, 126, 154925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, K.; Rockstroh, D.; Wagner, I.V.; Weise, S.; Tauscher, R.; Schwartze, J.T.; Loffler, D.; Buhligen, U.; Wojan, M.; Till, H.; et al. Evidence of early alterations in adipose tissue biology and function and its association with obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance in children. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, N.; Pomares-Millan, H.; Dannemann, A.; Giordano, G.N.; Joisten, C.; Korner, A.; Weghuber, D.; Weihrauch-Bluher, S.; Wiegand, S.; Holl, R.W.; et al. Who benefits most from outpatient lifestyle intervention? An IMI-SOPHIA study on pediatric individuals living with overweight and obesity. Obesity 2023, 31, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.A.; Evans, C.V.; Burda, B.U.; Walsh, E.S.; Eder, M.; Lozano, P. Screening for Obesity and Intervention for Weight Management in Children and Adolescents: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2017, 317, 2427–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weghuber, D.; Barrett, T.; Barrientos-Perez, M.; Gies, I.; Hesse, D.; Jeppesen, O.K.; Kelly, A.S.; Mastrandrea, L.D.; Sorrig, R.; Arslanian, S.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adolescents with Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2245–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.S.; Auerbach, P.; Barrientos-Perez, M.; Gies, I.; Hale, P.M.; Marcus, C.; Mastrandrea, L.D.; Prabhu, N.; Arslanian, S.; Investigators, N.N.T. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide for Adolescents with Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.S.; Bensignor, M.O.; Hsia, D.S.; Shoemaker, A.H.; Shih, W.; Peterson, C.; Varghese, S.T. Phentermine/Topiramate for the Treatment of Adolescent Obesity. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inge, T.H.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Helmrath, M.A. Five-Year Outcomes of Gastric Bypass in Adolescents as Compared with Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, J.R.; Jenkins, T.M.; Xie, C.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Harmon, C.M.; Helmrath, M.A.; Sisley, S.; Michalsky, M.P.; Brandt, M.; Inge, T.H. Ten-Year Outcomes after Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1656–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pas, K.G.H.; Lubrecht, J.W.; Hesselink, M.L.; Winkens, B.; van Dielen, F.M.H.; Vreugdenhil, A.C.E. The Effect of a Multidisciplinary Lifestyle Intervention on Health Parameters in Children versus Adolescents with Severe Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Kleber, M.; Lass, N.; Toschke, A.M. Body mass index patterns over 5 y in obese children motivated to participate in a 1-y lifestyle intervention: Age as a predictor of long-term success. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, E.; Hecht, L.; Marko, L.; Azmanov, H.; Groop, L.; Santoro, N.; Caprio, S.; Weiss, R. Predictors of responses to clinic-based childhood obesity care. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourdoumpa, A.; Paltoglou, G.; Charmandari, E. The Genetic Basis of Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuisson, A.C.; Zech, F.R.; Dassy, M.M.; Jodogne, N.B.; Beauloye, V.M. Determinants of weight loss in an interdisciplinary long-term care program for childhood obesity. ISRN Obes. 2012, 2012, 349384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southcombe, F.; Lin, F.; Krstic, S.; Sim, K.A.; Dennis, S.; Lingam, R.; Denney-Wilson, E. Targeted dietary approaches for the management of obesity and severe obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Obes. 2023, 13, e12564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel-Etayo, P.; Moreno, L.A.; Santabarbara, J.; Martin-Matillas, M.; Azcona-San Julian, M.C.; Marti Del Moral, A.; Campoy, C.; Marcos, A.; Garagorri, J.M.; Group, E.S. Diet quality index as a predictor of treatment efficacy in overweight and obese adolescents: The EVASYON study. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, C.N.; Jelalian, E.; Raynor, H.A.; Mehlenbeck, R.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.E.; Kaplan, J.; Flynn-O’Brien, K.; Wing, R.R. Early patterns of food intake in an adolescent weight loss trial as predictors of BMI change. Eat. Behav. 2010, 11, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allali, B.; Pereira, B.; Fillon, A.; Pouele, L.; Masurier, J.; Cardenoux, C.; Isacco, L.; Boirie, Y.; Duclos, M.; Thivel, D.; et al. The effectiveness of multidisciplinary weight loss interventions is associated with initial cardiorespiratory fitness in adolescents with obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2024, 19, e13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, J.M.; Xiao, L.; Chau, C.A.; Tinajero-Deck, L.; Srinivasan, S.; Rosas, L.G. Greater Improvement in Obesity Among Children With Prediabetes in a Clinical Weight Management Program. Child. Obes. 2024, 20, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Lerner-Geva, L.; Copperman, N.; Jacobson, M.S. Insulin resistance and parental obesity as predictors to response to therapeutic life style change in obese children and adolescents 10-18 years old. J. Adolesc. Health 2008, 43, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, Y.; Wolters, B.; Knop, C.; Reinehr, T. Components of the metabolic syndrome are negative predictors of weight loss in obese children with lifestyle intervention. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Kleber, M.; de Sousa, G.; Andler, W. Leptin concentrations are a predictor of overweight reduction in a lifestyle intervention. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2009, 4, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, A.; Evans, E.W.; Perkins, M.; Simione, M.; Cheng, E.R.; Luo, M.; Burgun, R.; Taveras, E.M.; Fiechtner, L. The association of food insecurity on body mass index change in a pediatric weight management intervention. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliakim, A.; Friedland, O.; Kowen, G.; Wolach, B.; Nemet, D. Parental obesity and higher pre-intervention BMI reduce the likelihood of a multidisciplinary childhood obesity program to succeed--a clinical observation. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 17, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, L.J.; Kutchman, E.M.; Berger, N.A.; Lawhun, S.A.; Cuttler, L.; Seabrook, R.C.; Horwitz, S.M. Parent involvement is associated with early success in obesity treatment. Clin. Pediatr. 2010, 49, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensignor, M.O.; Bramante, C.T.; Bomberg, E.M.; Fox, C.K.; Hale, P.M.; Kelly, A.S.; Mamadi, R.; Prabhu, N.; Harder-Lauridsen, N.M.; Gross, A.C. Evaluating potential predictors of weight loss response to liraglutide in adolescents with obesity: A post hoc analysis of the randomized, placebo-controlled SCALE Teens trial. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, B.M.; Rudser, K.D.; Abuzzahab, M.J.; Fox, C.K.; Coombes, B.J.; Bomberg, E.M.; Kelly, A.S. Predictors of weight-loss response with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment among adolescents with severe obesity. Clin. Obes. 2016, 6, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensignor, M.O.; Kelly, A.S.; Kunin-Batson, A.; Fox, C.K.; Freese, R.; Clark, J.; Rudser, K.D.; Bomberg, E.M.; Ryder, J.; Gross, A.C. Evaluating appetite/satiety hormones and eating behaviours as predictors of weight loss maintenance with GLP-1RA therapy in adolescents with severe obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2024, 19, e13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.H.; Afrooz, I.; Masalawala, M.S.; Watad, R.; Al Shaban, T.; Deeb, A. Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents: A Single-Center Study of Efficacy and Outcome Predictors. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2025; Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, E.R.; Jacobs, M.; Nadler, E.P. Preoperative exercise as a predictor of weight loss in adolescents and young adults following sleeve gastrectomy: A cohort study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghard, A.C.; Rahming, V.L.; Sonnett Fisher, A.; Zitsman, J.L.; Oberfield, S.E.; Fennoy, I. The Relationship between Metabolic Comorbidities and Post-Surgical Weight Loss Outcomes in Adolescents Undergoing Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 97, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysko, R.; Devlin, M.J.; Hildebrandt, T.B.; Brewer, S.K.; Zitsman, J.L.; Walsh, B.T. Psychological outcomes and predictors of initial weight loss outcomes among severely obese adolescents receiving laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancourt, D.; Jensen, C.D.; Duraccio, K.M.; Evans, E.W.; Wing, R.R.; Jelalian, E. Successful weight loss initiation and maintenance among adolescents with overweight and obesity: Does age matter? Clin. Obes. 2018, 8, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba-Albrecht, L.A.; Styne, D.M. Effect of puberty on body composition. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2009, 16, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, S.; Keller, K.M.; Lob-Corzilius, T.; Pott, W.; Reinehr, T.; Robl, M.; Stachow, R.; Tuschy, S.; Weidanz, I.; Widhalm, K.; et al. Predicting weight loss and maintenance in overweight/obese pediatric patients. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2014, 82, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensignor, M.O.; Freese, R.L.; Rudser, K.D.; Kelly, A.S.; Kunin-Batson, A.; Gross, A.C.; Bramante, C.; Shih, W.; Peterson, C.; Fox, C.K. Predictors of BMI reduction with phentermine/topiramate in adolescents with obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 1777–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Bonnefond, A.; Manzoor, J.; Shabbir, F.; Ayesha, H.; Philippe, J.; Durand, E.; Crouch, H.; Sand, O.; Ali, M.; et al. Genetic variants in LEP, LEPR, and MC4R explain 30% of severe obesity in children from a consanguineous population. Obesity 2015, 23, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucan, L.; Larifla, L.; Durand, E.; Rambhojan, C.; Armand, C.; Michel, C.T.; Billy, R.; Dhennin, V.; De Graeve, F.; Rabearivelo, I.; et al. High Prevalence of Rare Monogenic Forms of Obesity in Obese Guadeloupean Afro-Caribbean Children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzel, R.; Faust, H.; Bundalian, L.; Bluher, M.; Jasaszwili, M.; Kirstein, A.; Kobelt, A.; Korner, A.; Popp, D.; Wenzel, E.; et al. Detecting monogenic obesity: A systematic exome-wide workup of over 500 individuals. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, S.; O’Rahilly, S. Genetics of obesity in humans. Endocr. Rev. 2006, 27, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Y.; de Souza, R.J.; Gibson, W.T.; Meyre, D. A systematic review of genetic syndromes with obesity. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 603–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Hebebrand, J.; Friedel, S.; Toschke, A.M.; Brumm, H.; Biebermann, H.; Hinney, A. Lifestyle intervention in obese children with variations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. Obesity 2009, 17, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, K.; van den Akker, E.; Argente, J.; Bahm, A.; Chung, W.K.; Connors, H.; De Waele, K.; Farooqi, I.S.; Gonneau-Lejeune, J.; Gordon, G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of setmelanotide, an MC4R agonist, in individuals with severe obesity due to LEPR or POMC deficiency: Single-arm, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haqq, A.M.; Chung, W.K.; Dollfus, H.; Haws, R.M.; Martos-Moreno, G.A.; Poitou, C.; Yanovski, J.A.; Mittleman, R.S.; Yuan, G.; Forsythe, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor agonist, in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome and Alstrom syndrome: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial with an open-label period. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalakis, M.; Till, H.; Kiess, W.; Weiner, R.A. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in an adolescent patient with Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a monogenic obesity disorder. Obes. Surg. 2010, 20, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.R.; Elahmedi, M.O.; Al Qahtani, A.R.; Lee, J.; Butler, M.G. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome: A matched-control study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016, 12, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censani, M.; Conroy, R.; Deng, L.; Oberfield, S.E.; McMahon, D.J.; Zitsman, J.L.; Leibel, R.L.; Chung, W.K.; Fennoy, I. Weight loss after bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents with MC4R mutations. Obesity 2014, 22, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Reyes, G.; Alavez, F.J.L.; Tejero, M.E. Genetics of Common Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2025, 1553, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, R.A.J.; Wade, K.H.; Hui, Q.; Arias, J.D.; Yin, X.; Christiansen, M.R.; Yengo, L.; Preuss, M.H.; Nakabuye, M.; Rocheleau, G.; et al. Polygenic prediction of body mass index and obesity through the life course and across ancestries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3151–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Wade, K.H.; Zahid, S.; Brancale, J.; Xia, R.; Distefano, M.; Senol-Cosar, O.; Haas, M.E.; Bick, A.; et al. Polygenic Prediction of Weight and Obesity Trajectories from Birth to Adulthood. Cell 2019, 177, 587–596.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Uhm, J.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; van Haelst, M.M.; Jansen, P.R.; van den Akker, E.L.T. Polygenic Childhood Obesity: Integrating Genetics and Environment for Early Intervention. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2025; Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Llewellyn, C.; Sanderson, S.; Plomin, R. The FTO gene and measured food intake in children. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitkamp, M.; Siegrist, M.; Molnos, S.; Brandmaier, S.; Wahl, S.; Langhof, H.; Grallert, H.; Halle, M. Obesity Genes and Weight Loss During Lifestyle Intervention in Children With Obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, e205142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xiao, W.C.; Zhao, J.J.; Shan, R.; Heitkamp, M.; Zhang, X.R.; Liu, Z. Gene variants and the response to childhood obesity interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollensted, M.; Fogh, M.; Schnurr, T.M.; Kloppenborg, J.T.; Have, C.T.; Ruest Haarmark Nielsen, T.; Rask, J.; Asp Vonsild Lund, M.; Frithioff-Bojsoe, C.; Ostergaard Johansen, M.; et al. Genetic Susceptibility for Childhood BMI has no Impact on Weight Loss Following Lifestyle Intervention in Danish Children. Obesity 2018, 26, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita-Ruiz, A.; Gonzalez-Gil, E.M.; Ruperez, A.I.; Llorente-Cantarero, F.J.; Pastor-Villaescusa, B.; Alcala-Fdez, J.; Moreno, L.A.; Gil, A.; Gil-Campos, M.; Bueno, G.; et al. Evaluation of the Predictive Ability, Environmental Regulation and Pharmacogenetics Utility of a BMI-Predisposing Genetic Risk Score during Childhood and Puberty. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.; Cordioli, M.; Tozzo, V.; Urbut, S.; Arumae, K.; Smit, R.A.J.; Lee, J.; Li, J.H.; Janucik, A.; Ding, Y.; et al. Association between plausible genetic factors and weight loss from GLP1-RA and bariatric surgery. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Stocco, G.; Theken, K.N.; Dickson, A.; Feng, Q.; Karnes, J.H.; Mosley, J.D.; El Rouby, N. Pharmacogenomics polygenic risk score: Ready or not for prime time? Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butte, N.F.; Christiansen, E.; Sorensen, T.I. Energy imbalance underlying the development of childhood obesity. Obesity 2007, 15, 3056–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alman, K.L.; Lister, N.B.; Garnett, S.P.; Gow, M.L.; Aldwell, K.; Jebeile, H. Dietetic management of obesity and severe obesity in children and adolescents: A scoping review of guidelines. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S. Effects of exercise in the treatment of overweight and obese children and adolescents: A systematic review of meta-analyses. J. Obes. 2013, 2013, 783103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiri, B.; Valizadeh, M.; Amini, S.; Kelishadi, R.; Hosseinpanah, F. Risk factors, cutoff points, and definition of metabolically healthy/unhealthy obesity in children and adolescents: A scoping review of the literature. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nso-Roca, A.P.; Cortes Castell, E.; Carratala Marco, F.; Sanchez Ferrer, F. Insulin Resistance as a Diagnostic Criterion for Metabolically Healthy Obesity in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 73, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Garcia, J.M.; Romero-Saldana, M.; Molina-Recio, G.; Fonseca-Del Pozo, F.J.; Raya-Cano, E.; Molina-Luque, R. Diagnostic accuracy of anthropometric indices for metabolically healthy obesity in child and adolescent population. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Mohd Zin, R.M.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Yahya, A.; Nur Zati Iwani, A.K.; Md Zain, F.; Hong, J.Y.H.; Mokhtar, A.H.; Wan Mohamud, W.N. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of metabolically healthy obese versus metabolically unhealthy obese school children. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 971202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukovic, R.; Dos Santos, T.J.; Ybarra, M.; Atar, M. Children With Metabolically Healthy Obesity: A Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadda, K.R.; Cheng, T.S.; Ong, K.K. GLP-1 agonists for obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahagan, S. Development of eating behavior: Biology and context. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012, 33, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, I.P.M.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; Wake, M.; Qureshi, F.; van der Ende, J.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Tiemeier, H.; Jansen, P.W. Eating behavior and body composition across childhood: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, D.D.; Clausen, L.; Bruun, J.M. Eating behavior profiles in children following a 10-week lifestyle camp due to overweight/obesity and low quality of life: A latent profile analysis on eating behavior. Eat. Behav. 2025, 57, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, T.W.; Camilleri, M.; Acosta, A. Pharmacotherapy for Obesity: Recent Updates. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 17, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.S. Current and future pharmacotherapies for obesity in children and adolescents. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, V.; Nimmala, S.; Karzar, N.H.; Bredella, M.; Misra, M. One-Year Self-Reported Appetite Is Similar in Adolescents with Obesity Who Do or Do Not Undergo Sleeve Gastrectomy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, J.R.; Gross, A.C.; Fox, C.K.; Kaizer, A.M.; Rudser, K.D.; Jenkins, T.M.; Ratcliff, M.B.; Kelly, A.S.; Kirk, S.; Siegel, R.M.; et al. Factors associated with long-term weight-loss maintenance following bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligthart, K.A.M.; Buitendijk, L.; Koes, B.W.; van Middelkoop, M. The association between ethnicity, socioeconomic status and compliance to pediatric weight-management interventions—A systematic review. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 11, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, M.; Castro, I.; Sharifi, M.; Perkins, M.; O’Connor, G.; Sandel, M.; Taveras, E.M.; Fiechtner, L. Unmet Social Needs and Adherence to Pediatric Weight Management Interventions: Massachusetts, 2017-2019. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, S251–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.; Snoeck Henkemans, S.; van Teeffelen, J.; Kornelisse, K.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Koes, B.W.; van Middelkoop, M. Determinants of dropout and compliance of children participating in a multidisciplinary intervention programme for overweight and obesity in socially deprived areas. Fam. Pract. 2023, 40, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danieles, P.K.; Ybarra, M.; Van Hulst, A.; Barnett, T.A.; Mathieu, M.E.; Kakinami, L.; Drouin, O.; Bigras, J.L.; Henderson, M. Determinants of attrition in a pediatric healthy lifestyle intervention: The CIRCUIT program experience. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 15, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Lev, H.; Vega, Y.; Kalamitzky, N.; Interator, H.; Cohen, S.; Lubetzky, R. Factors Associated With Treatment Adherence to a Lifestyle Intervention Program for Children With Obesity: The Experience of a Large Tertiary Care Pediatric Hospital. Clin. Pediatr. 2023, 62, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, M.K.; Caccavale, L.J.; Adams, E.L.; Burnette, C.B.; LaRose, J.G.; Raynor, H.A.; Wickham, E.P., 3rd; Mazzeo, S.E. Parent Involvement in Adolescent Obesity Treatment: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Camilleri, M.; Shin, A.; Vazquez-Roque, M.I.; Iturrino, J.; Burton, D.; O’Neill, J.; Eckert, D.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Quantitative gastrointestinal and psychological traits associated with obesity and response to weight-loss therapy. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 537–546.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Camilleri, M.; Abu Dayyeh, B.; Calderon, G.; Gonzalez, D.; McRae, A.; Rossini, W.; Singh, S.; Burton, D.; Clark, M.M. Selection of Antiobesity Medications Based on Phenotypes Enhances Weight Loss: A Pragmatic Trial in an Obesity Clinic. Obesity 2021, 29, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, L.; Anazco, D.; O’Connor, T.; Hurtado, M.D.; Ghusn, W.; Campos, A.; Fansa, S.; McRae, A.; Madhusudhan, S.; Kolkin, E.; et al. Genetic and physiological insights into satiation variability predict responses to obesity treatment. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 1655–1666.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garutti, M.; Sirico, M.; Noto, C.; Foffano, L.; Hopkins, M.; Puglisi, F. Hallmarks of Appetite: A Comprehensive Review of Hunger, Appetite, Satiation, and Satiety. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, L.; Ghusn, W.; Feris, F.; Campos, A.; Sacoto, D.; De la Rosa, A.; McRae, A.; Rieck, T.; Mansfield, S.; Ewoldt, J.; et al. Phenotype tailored lifestyle intervention on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults with obesity: A single-centre, non-randomised, proof-of-concept study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Camilleri, M.; Burton, D.; O’Neill, J.; Eckert, D.; Carlson, P.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Exenatide in obesity with accelerated gastric emptying: A randomized, pharmacodynamics study. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halawi, H.; Khemani, D.; Eckert, D.; O’Neill, J.; Kadouh, H.; Grothe, K.; Clark, M.M.; Burton, D.D.; Vella, A.; Acosta, A.; et al. Effects of liraglutide on weight, satiation, and gastric functions in obesity: A randomised, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.J.; Bazerbachi, F.; Calderon, G.; Prokop, L.J.; Gomez, V.; Murad, M.H.; Acosta, A.; Camilleri, M.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K. Changes in Time of Gastric Emptying After Surgical and Endoscopic Bariatrics and Weight Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 57–68.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.J.; Storm, A.C.; Bazerbachi, F.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K. Accelerated gastric emptying is associated with improved aspiration efficiency in obesity. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019, 6, e000273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, V.; Woodman, G.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K. Delayed gastric emptying as a proposed mechanism of action during intragastric balloon therapy: Results of a prospective study. Obesity 2016, 24, 1849–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Nava, G.; Jaruvongvanich, V.; Storm, A.C.; Maselli, D.B.; Bautista-Castano, I.; Vargas, E.J.; Matar, R.; Acosta, A.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K. Personalization of Endoscopic Bariatric and Metabolic Therapies Based on Physiology: A Prospective Feasibility Study with a Single Fluid-Filled Intragastric Balloon. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3347–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thivel, D.; Genin, P.M.; Mathieu, M.E.; Pereira, B.; Metz, L. Reproducibility of an in-laboratory test meal to assess ad libitum energy intake in adolescents with obesity. Appetite 2016, 105, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnbach, S.N.; Thivel, D.; Meyermann, K.; Keller, K.L. Intake at a single, palatable buffet test meal is associated with total body fat and regional fat distribution in children. Appetite 2015, 92, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.V.E.; Moore, R.H.; Chittams, J.; Jones, E.; O’Malley, L.; Fisher, J.O. Identifying behavioral phenotypes for childhood obesity. Appetite 2018, 127, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyper, A.H.; Kopfer, K.; Huang, W.M.; Re’em, Y. Increased hunger and speed of eating in obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 27, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.K.; Molitor, S.J.; Vock, D.M.; Peterson, C.B.; Crow, S.J.; Gross, A.C. Appetitive and psychological phenotypes of pediatric patients with obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2024, 19, e13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutelle, K.N.; Peterson, C.B.; Crosby, R.D.; Rydell, S.A.; Zucker, N.; Harnack, L. Overeating phenotypes in overweight and obese children. Appetite 2014, 76, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofsteenge, G.H.; Chinapaw, M.J.; Delemarre-van de Waal, H.A.; Weijs, P.J. Validation of predictive equations for resting energy expenditure in obese adolescents. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedogni, G.; Bertoli, S.; De Amicis, R.; Foppiani, A.; De Col, A.; Tringali, G.; Marazzi, N.; De Cosmi, V.; Agostoni, C.; Battezzati, A.; et al. External Validation of Equations to Estimate Resting Energy Expenditure in 2037 Children and Adolescents with and 389 without Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamini, S.; Caroli, D.; Bondesan, A.; Abbruzzese, L.; Sartorio, A. Measured vs estimated resting energy expenditure in children and adolescents with obesity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawi, O.; Koster, E.C.; Welling, M.S.; Boeters, S.C.M.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; van Haelst, M.M.; van der Voorn, B.; de Groot, C.J.; van den Akker, E.L.T. Resting Energy Expenditure and Body Composition in Children and Adolescents With Genetic, Hypothalamic, Medication-Induced or Multifactorial Severe Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 862817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention | Authors, Year | Study Design and Population | Key Predicting Factors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle | Prinz et al., 2023 | Registry cohort of 12,453 children and adolescents with overweight/obesity (median age 11.5 years, BMI z-score 2.06, 52.6% girls) who participated in outpatient lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention for up to 2 years | Younger age, lower baseline BMI z-score, larger initial reduction in BMI z-score, less social deprivation predicted moderate/pronounced BMI z-score reduction | [22] |

| Lifestyle | van de Pas et al., 2022 | Longitudinal study evaluating outcomes at 1 and 2 years of multidisciplinary lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention in 83 children (mean age 8.3 years, BMI z-score 4.07, 47% female) and 77 adolescents (mean age 15.2 years, BMI z-score 3.96, 61% female) with severe obesity | Younger age predicted greater reduction in BMI z-score after 1 and 2 years of intervention | [29] |

| Lifestyle | Reinehr et al., 2010 | Longitudinal study over 5 years following 1-year outpatient lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention in 663 children (mean age 10.6 years, mean BMI z-score 2.46, 55% female) | Younger age (<8 years) predicted greater reduction in BMI z-score over 5 years, while older age (>13 years) predicted the least reduction | [30] |

| Lifestyle | Hagman et al., 2018 | Prospective cohort of 434 youths (mean age 12.4 years, mean BMI z-score 2.4, 64.5% female) who received lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention for 35.9 ± 20.8 months | Male sex and pubertal adolescents predicted poor response (defined as increase in BMI z-score over time), while higher baseline BMI and carriers of FTO allele were protective factors | [31] |

| Lifestyle | Vourdoumpa et al., 2023 | Systematic review of 27 studies involving 7928 children and adolescents with overweight/obesity (age range 4.5–20 years) examining the influence of genetic variants on response to multidisciplinary lifestyle interventions | Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in 24 genetic loci were associated with greater or smaller BMI/body composition changes in response to lifestyle intervention | [32] |

| Lifestyle | Dubuisson et al., 2012 | Retrospective study of 144 children with obesity (mean age 10.5 years, mean BMI z-score 2.73, 59% female) who participated in family-targeted interdisciplinary lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) program who had ≥2 interdisciplinary visits and ≥1 year of treatment | Increased levels of physical activity and daily water intake at baseline predicted greater BMI z-score reduction after 9 months of lifestyle intervention, while higher intake of soft drinks was a negative predictor | [33] |

| Lifestyle | Southcombe et al., 2023 | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 125 studies of dietary intervention in children and adolescents aged 2–18 years with obesity | Dietary interventions with greater energy deficits were associated with greater BMI reductions, while interventions with no specified energy target were associated with slight increase in BMI | [34] |

| Lifestyle | De Miguel-Etayo et al., 2019 | Prospective study of 117 adolescents (mean age 14.62 years, mean BMI z-score 2.61, 56.4% female) following 13-month multidisciplinary lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Higher diet quality index scores predicted greater BMI and fat mass index reductions | [35] |

| Lifestyle | Hart et al., 2010 | Prospective study of 72 adolescents (mean age 14.21 years, mean BMI 30.99 kg/m2, 73.6% female) following 16-week multidisciplinary lifestyle (dietary, physical activity and behavioral) intervention | Higher initial frequency of intake of vegetables and increased frequency of intake of fruits and reduced-calorie snack foods over the 1st 4 weeks of treatment is associated with greater reduction in BMI | [36] |

| Lifestyle | Allali et al., 2024 | Prospective study of 165 adolescents (mean age 13.3 years, mean BMI z-score 2.32, 61.2% female) following 16-week multidisciplinary lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Higher baseline cardiorespiratory fitness predicted greater reductions in weight, BMI, and fat mass, and predicted increase in lean mass following the intervention | [37] |

| Lifestyle | Tester et al., 2024 | Retrospective longitudinal analysis of 733 children and adolescents (mean age 12.1 years, mean BMI z-score 2.2, 51.7% female) with overweight/obesity without diabetes in a weight management clinic including meeting with a provider, dietitian, exercise specialist, and psychologist with baseline HbA1c within 90 days of first visit | Baseline prediabetes predicted greater reduction in BMI percent of the 95th percentile compared to children with normal baseline HbA1c | [38] |

| Lifestyle | Pinhas-Hamiel et al., 2008 | Retrospective study of 134 adolescents with obesity (mean age 13.4 years, 44% female) enrolled in a lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Higher baseline fasting insulin, homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and the presence of obesity or obesity-related comorbidity in both parents were associated with lower likelihood of BMI z-score improvement | [39] |

| Lifestyle | Uysal et al., 2013 | Longitudinal study of 484 children with obesity (median age 11.1 years, mean BMI z-score 2.42, 57% female) who participated in a 1-year lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Higher baseline insulin resistance, increased waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio, higher blood pressure, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated uric acid were negative predictors of BMI z-score reduction | [40] |

| Lifestyle | Reinehr et al., 2009 | Longitudinal study of 248 children with obesity (mean age 10.6 years, mean BMI 2.43, 53% female) who participated in a 1-year lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Higher baseline leptin was a negative predictor of reduction in BMI z-score, waist circumference, and percentage body fat following lifestyle intervention | [41] |

| Lifestyle | Persaud et al., 2023 | Longitudinal cohort of 201 children (mean age 9.57 years, mean %BMIp95 113.67, 44.28% female) who participated in a lifestyle-based pediatric weight management intervention (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) | Household food insecurity was associated with increased BMI and %BMIp95 compared to the food-secure group | [42] |

| Lifestyle | Eliakim et al., 2004 | Prospective study of 77 children with obesity (mean age 10.2 years, mean BMI 35.9 kg/m2, 49% female) who participated in a 12-month lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Higher baseline BMI percentile and parental obesity were associated with less favorable response | [43] |

| Lifestyle | Heinberg et al., 2010 | Prospective study of 104 children and adolescents with obesity (mean age 11.63 years, mean BMI 33.03 kg/m2, 65% female) and their caregivers who participated in a 12-week lifestyle (dietary, physical activity, and behavioral) intervention | Lower baseline parental involvement was associated with reduced likelihood of weight loss | [44] |

| Pharmacotherapy | Bensignor et al., 2023 | Post-hoc analysis of adolescents enrolled in the SCALE Teens trial randomized to receive liraglutide (n = 125, mean age 14.6 years, mean BMI 35.3 kg/m2, 61.9% female) versus placebo (n = 126, mean age 14.5 years, mean BMI 35.8 kg/m2, 61.9% female) for 56 weeks | Early response to liraglutide (≥4% reduction in BMI at week 16) was a positive predictor for BMI and body weight reduction at week 56 compared to early non-responders | [45] |

| Pharmacotherapy | Nathan et al., 2015 | Post-hoc analysis of pooled data from 2 clinical trials of 32 adolescents (mean age 14.3 years, mean BMI 39.8 kg/m2, 69% female) treated with exenatide for 3 months | Female sex and higher baseline appetite were positive predictors of BMI change after 3 months of exenatide treatment | [46] |

| Pharmacotherapy | Bensignor et al., 2024 | Post-hoc analysis of 66 adolescents (mean age 16 years, BMI 36.87 kg/m2, 47% female) enrolled in a clinical trial who had achieved ≥5% BMI reduction with meal-replacement therapy and were subsequently randomized to exenatide or placebo for 52 weeks | Lower leptin response to meals at baseline was associated with greater weight loss maintenance in those receiving exenatide | [47] |

| Metabolic and bariatric surgery | Beck et al., 2025 | Prospective, observational cohort study of 73 adolescents (mean age 17.6 years, mean BMI z-score 2.63, female 65.8%) undergoing MBS (87.7% sleeve gastrectomy, 12.3% gastric bypass) followed for up to 30 months post-surgery | Higher preoperative BMI was a negative predictor for achieving a >35% reduction in BMI z-score at 12 months | [48] |

| Metabolic and bariatric surgery | Mackey et al., 2019 | Prospective study of 173 adolescents and young adults (mean age 16.6 years, mean preoperative BMI 50 kg/m2, 74% female) undergoing sleeve gastrectomy with self-reported preoperative physical activity levels | Higher preoperative exercise predicted greater weight loss at 6 months and (marginally) 12 months post-surgery; lower preoperative BMI was a positive predictor | [49] |

| Metabolic and bariatric surgery | Burghard et al., 2024 | Retrospective study of 151 adolescents (mean age 15.9 years, 77.5% female) who underwent sleeve gastrectomy | Higher systolic blood pressure predicted greater reduction in absolute BMI and BMI z-score at 6 and 12 months; higher HbA1c predicted greater reduction in BMI z-score at 6 months | [50] |

| Metabolic and bariatric surgery | Sysko et al., 2012 | Prospective study of 101 adolescents with obesity (mean age 15.8 years, mean BMI 47.23 kg/m2, 72.3% female) who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and were followed for 1 year postoperatively | Higher baseline family conflict was associated with reduced postoperative BMI reduction | [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saba, L.; Acosta, A.J.; Kelly, A.S.; Kumar, S. Obesity Phenotyping in Children and Adolescents: Next Steps Towards Precision Medicine in Pediatric Obesity. Nutrients 2026, 18, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020303

Saba L, Acosta AJ, Kelly AS, Kumar S. Obesity Phenotyping in Children and Adolescents: Next Steps Towards Precision Medicine in Pediatric Obesity. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020303

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaba, Leslie, Andres J. Acosta, Aaron S. Kelly, and Seema Kumar. 2026. "Obesity Phenotyping in Children and Adolescents: Next Steps Towards Precision Medicine in Pediatric Obesity" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020303

APA StyleSaba, L., Acosta, A. J., Kelly, A. S., & Kumar, S. (2026). Obesity Phenotyping in Children and Adolescents: Next Steps Towards Precision Medicine in Pediatric Obesity. Nutrients, 18(2), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020303