Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Systemic Outcomes in Patients with Glaucoma: A Real-World Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

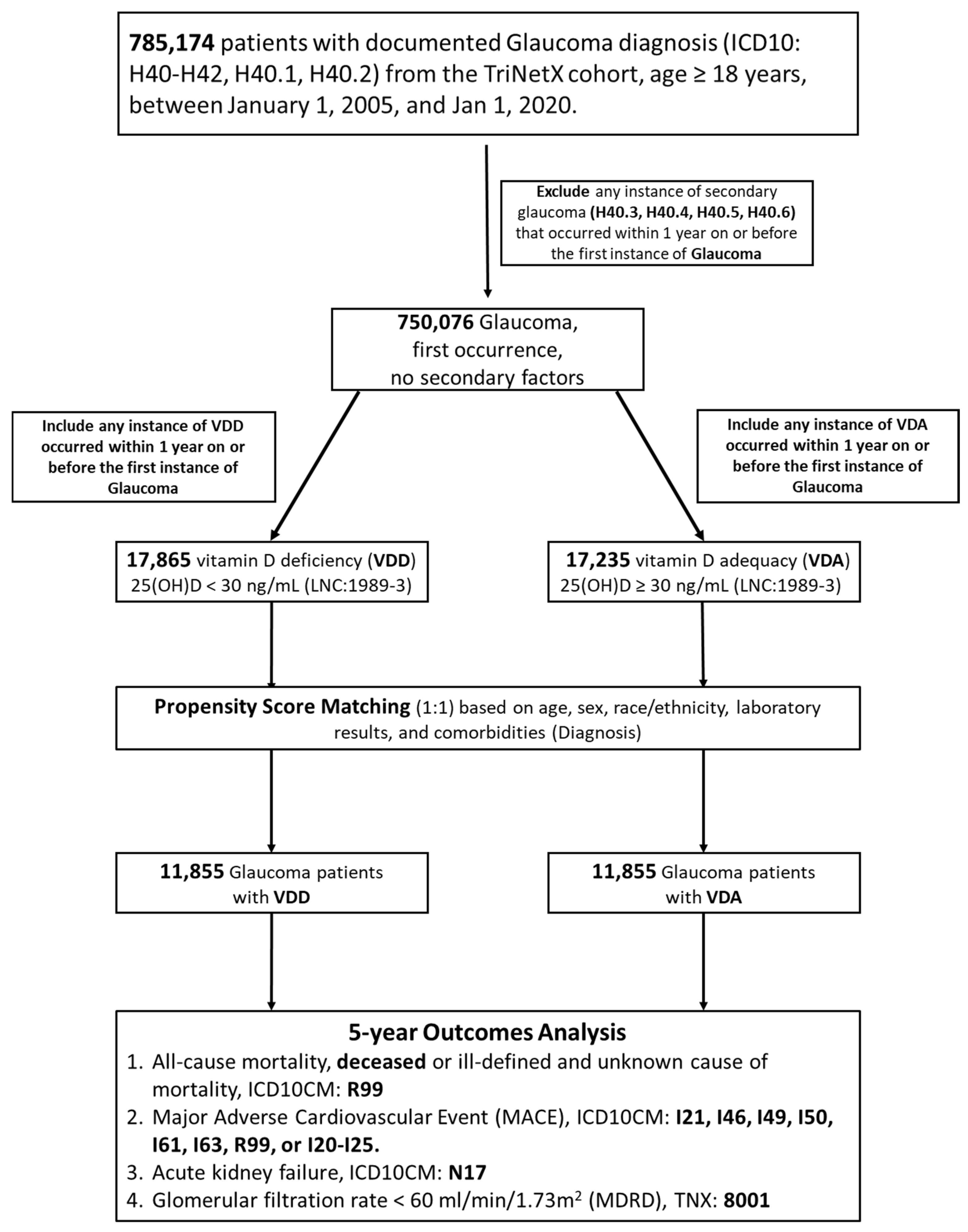

2.2. Study Population and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Index Date and Follow-Up

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Propensity Score Matching and Handling of Confounders

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.7. Sensitivity Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Identification, Baseline Characteristics, and Propensity Score Matching

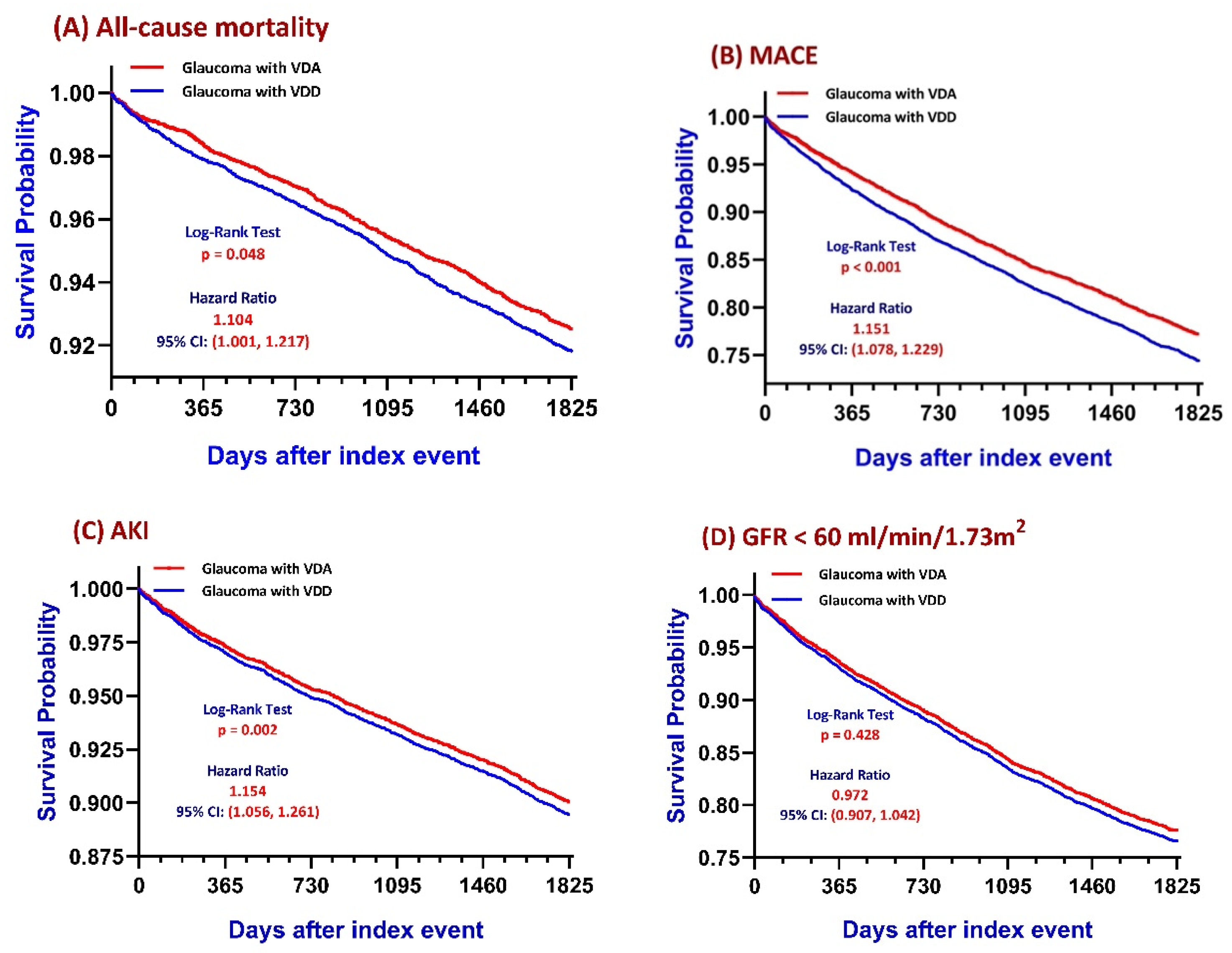

3.2. Primary Outcomes: Kaplan–Meier Survival Analysis

3.3. Landmark Analyses of Time-Dependent Outcome Differences

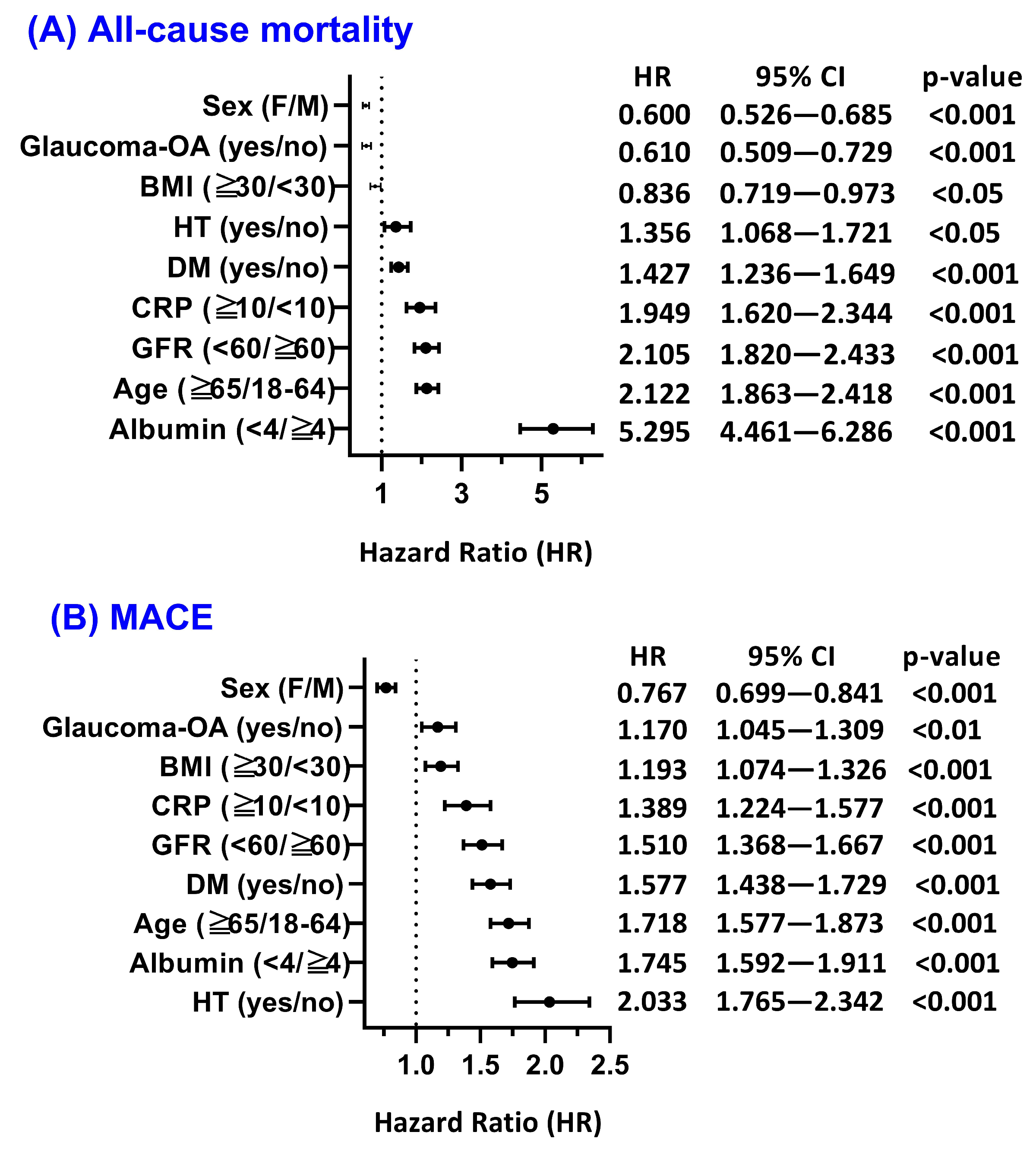

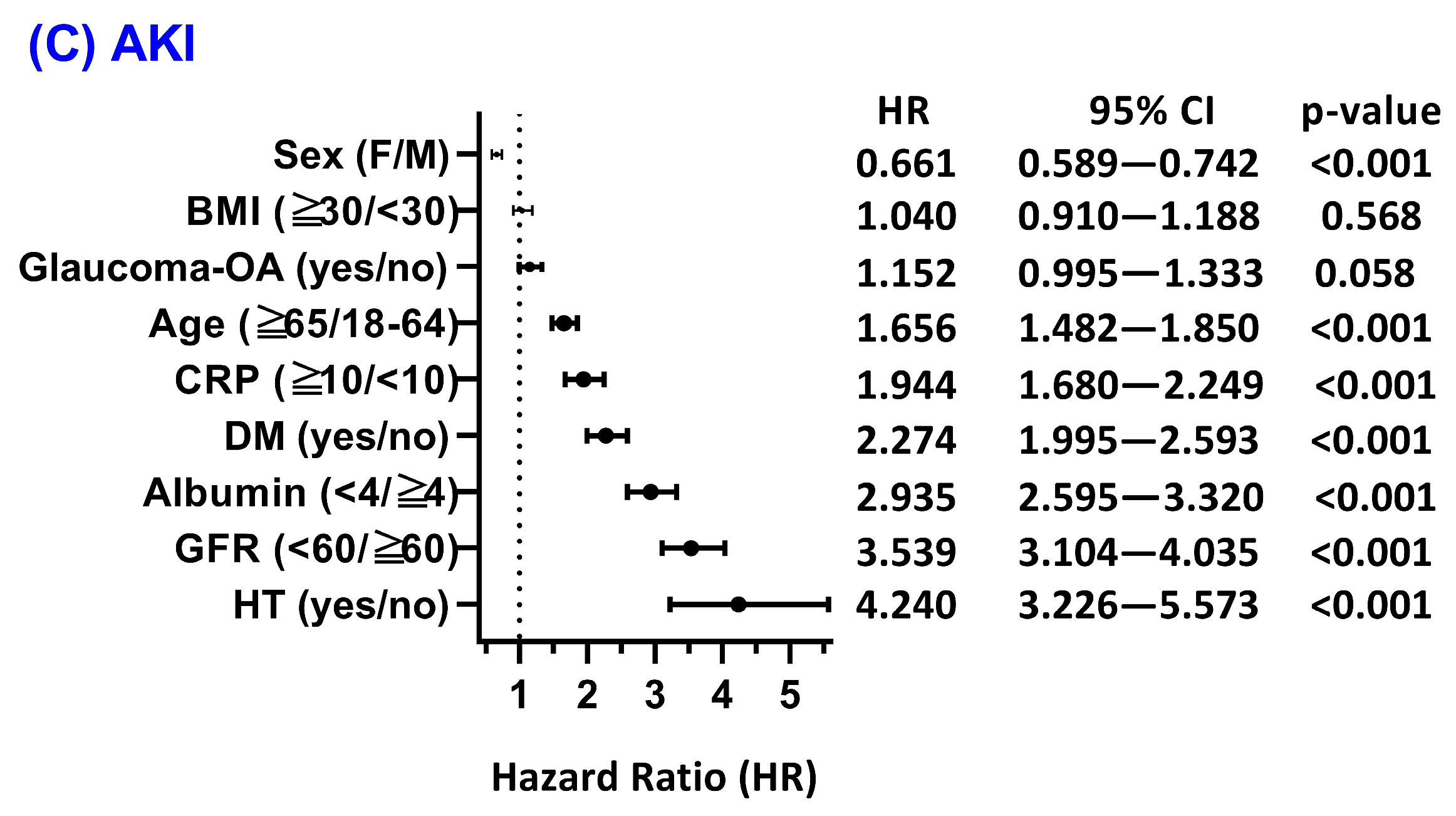

3.4. Subgroup and Effect Modification Analyses

3.5. Sensitivity Analyses

3.6. Competing Risk Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 25(OH)D | 25-Hydroxyvitamin D |

| ACEI | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| ARB | Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| MDRD | Modification of Diet in Renal Disease |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and Pyrin Domain-Containing Protein 3 (Inflammasome) |

| POAG | Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma |

| PACG | Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma |

| RAAS | Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System |

| VDA | Vitamin D Adequacy |

| VDD | Vitamin D Deficiency |

| VDR | Vitamin D Receptor |

References

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, F.Y.C.; Song, H.; Tan, B.K.J.; Teo, C.; Wong, E.; Boey, P.; Cheng, C.-Y. Bidirectional association between glaucoma and chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 49, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jeon, J.-S.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, J.K. Prediction of the Cause of Glaucoma Disease Identified by Glaucoma Optical Coherence Tomography Test in Relation to Diabetes and Hypertension at a National Hospital in Seoul: A Retrospective Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wey, S.; Amanullah, S.; Spaeth, G.L.; Ustaoglu, M.; Rahmatnejad, K.; Katz, L.J. Is primary open-angle glaucoma an ocular manifestation of systemic disease? Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 257, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Li, D. The pivotal role of inflammatory factors in glaucoma: A systematic review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1577200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wareham, L.K.; Calkins, D.J. The Neurovascular Unit in Glaucomatous Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaranta, L.; Galbussera, A.; Tettamanti, M.; Novella, A.; Pasina, L.; Fortino, I.; Leoni, O.; Oddone, F.; Giammaria, S.; Kużniak, M.; et al. Relationships Among Glaucoma, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Mortality. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 4403–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, R.; Hodge, D.; Kohli, D.; Roddy, G. Multiple Systemic Vascular Risk Factors Are Associated with Low-Tension Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2021, 31, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Villanueva, C.; Millá, E.; Bolarín, J.; García-Medina, J.; Cruz-Espinosa, J.; Benítez-Del-Castillo, J.; Salgado-Borges, J.; Hernández-Martínez, F.; Bendala-Tufanisco, E.; Andrés-Blasco, I.; et al. Impact of Systemic Comorbidities on Ocular Hypertension and Open-Angle Glaucoma, in a Population from Spain and Portugal. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, T.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deb, D.; Yoon, D.; Kong, J.; Thadhani, R.; Li, Y. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D Promotes Negative Feedback Regulation of TLR Signaling via Targeting MicroRNA-155–SOCS1 in Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3687–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, S.; Shao, Q.; Jin, B.; Zhang, Q.-Y. 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 attenuates tumor necrosis factor-α-induced endothelial cell injury by modulating the tumor necrosis factor-α/nuclear factor kappa-B pathway. Cytojournal 2025, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldman, C.; Cantorna, M.; DeLuca, H. Expression of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) receptor in the immune system. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 374, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemire, J.; Archer, D.; Beck, L.; Spiegelberg, H. Immunosuppressive actions of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: Preferential inhibition of Th1 functions. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Yang, M. Trends of serum 25(OH) vitamin D and association with cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: From NHANES survey cycles 2001–2018. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1328136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiri, B.; Abdalla, A.; Osman, M.; Ahmed, S.; Hassan, M.; Bachuwa, G. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A narrative review. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, J. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: NHANES 2007–2018 results. Clinics 2024, 79, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittermann, A.; Trummer, C.; Theiler-Schwetz, V.; Lerchbaum, E.; März, W.; Pilz, S. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Disease: An Updated Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöttker, B.; Saum, K.; Perna, L.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.; Holleczek, B.; Brenner, H. Is vitamin D deficiency a cause of increased morbidity and mortality at older age or simply an indicator of poor health? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 29, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; Trummer, C.; Theiler-Schwetz, V.; Grübler, M.; Verheyen, N.; Odler, B.; Karras, S.; Zittermann, A.; März, W. Critical Appraisal of Large Vitamin D Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchebner, D.; Bartosch, P.; Malmgren, L.; McGuigan, F.; Gerdhem, P.; Åkesson, K. The Association Between Vitamin D, Frailty and Progression of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 6139–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.-N.; Zhang, X.; Ling, X.; Bui, C.; Wang, Y.-M.; Ip, P.; Chu, W.; Chen, L.-J.; Tham, C.; Yam, J.; et al. Vitamin D and Ocular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.T.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.; Won, Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, K. The Relationship between Vitamin D and Glaucoma: A Kangbuk Samsung Health Study. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 30, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhary, K.; Alqahtani, L.; Aljaser, F.; Abudawood, M.; Almubarak, F.; Algowaifly, S.; Jamous, K.; Fahmy, R. Association of Vitamin D deficiency with primary glaucoma among Saudi population—A pilot study. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 35, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.; Jammal, A.; Medeiros, F. Association Between Serum Vitamin D Level and Rates of Structural and Functional Glaucomatous Progression. J. Glaucoma 2022, 31, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Johnson, K.; Larson, J.; Thomas, F.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Bollinger, K.; Chen, Z.; Watsky, M. Association of vitamin D with incident glaucoma: Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. J. Investig. Med. 2021, 69, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanso, N.; Hashimi, M.; Amin, H.; Day, A.; Drenos, F. No Evidence That Vitamin D Levels or Deficiency Are Associated with the Risk of Open-Angle Glaucoma in Individuals of European Ancestry: A Mendelian Randomisation Analysis. Genes 2024, 15, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, X.; Timofeeva, M.; He, Y.; Spiliopoulou, A.; Wei, W.-Q.; Gifford, A.; Wu, H.; Varley, T.; Joshi, P.; et al. Phenome-wide Mendelian-randomization study of genetically determined vitamin D on multiple health outcomes using the UK Biobank study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, B.; Shah, P.; Sii, F.; Hunter, D.; Carnt, N.; White, A. Low systemic vitamin D as a potential risk factor in primary open-angle glaucoma: A review of current evidence. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 105, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Xiao, P.; Fan, Z.; Wang, H.; Yan, Z. Global and regional prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in population-based studies from 2000 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 7.9 million participants. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1070808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, Molecular Mechanism of Action, and Pleiotropic Effects. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 365–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstuyf, A.; Carmeliet, G.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Vitamin D: A pleiotropic hormone. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adorini, L. Intervention in autoimmunity: The potential of vitamin D receptor agonists. Cell Immunol. 2005, 233, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rao, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Fang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; et al. Vitamin D Receptor Inhibits NLRP3 Activation by Impeding Its BRCC3-Mediated Deubiquitination. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankers, W.; Davelaar, N.; van Hamburg, J.P.; van de Peppel, J.; Colin, E.M.; Lubberts, E. Human Memory Th17 Cell Populations Change Into Anti-inflammatory Cells with Regulatory Capacity Upon Exposure to Active Vitamin D. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Kong, J.; Wei, M.; Chen, Z.F.; Liu, S.Q.; Cao, L.P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.C.; Qiao, G.; Uskokovic, M.; Xiang, W.; Zheng, W.; Kong, J. Vitamin D: A negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system and blood pressure. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 89–90, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrukhova, O.; Slavic, S.; Zeitz, U.; Riesen, S.C.; Heppelmann, M.S.; Ambrisko, T.D.; Markovic, M.; Kuebler, W.M.; Erben, R.G. Vitamin D is a regulator of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and arterial stiffness in mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos, I.; Marginean, O. Links between Vitamin D Deficiency and Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 109275. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, J.; Deb, D.K.; Chang, A.; Li, Y.C. Vitamin D receptor attenuates renal fibrosis by suppressing the renin-angiotensin system. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, I.; Waku, T.; Aoki, M.; Abe, R.; Nagai, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Nakajima, Y.; Ohkido, I.; Yokoyama, K.; Miyachi, H.; et al. A nonclassical vitamin D receptor pathway suppresses renal fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 4579–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bragança, A.C.; Volpini, R.A.; Mehrotra, P.; Andrade, L.; Basile, D.P. Vitamin D deficiency contributes to vascular damage in sustained ischemic acute kidney injury. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bragança, A.C.; Volpini, R.A.; Canale, D.; Gonçalves, J.G.; Shimizu, M.H.; Sanches, T.R.; Seguro, A.C.; Andrade, L. Vitamin D deficiency aggravates ischemic acute kidney injury in rats. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Han, X.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, L.; Hong, W.; Xing, X. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 attenuates oxidative stress-induced damage in human trabecular meshwork cells by inhibiting TGFβ-SMAD3-VDR pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli-Batters, A.; Lamont, H.C.; Elghobashy, M.; Masood, I.; Hill, L.J. The role of Vitamin D3 in ocular fibrosis and its therapeutic potential for the glaucomatous trabecular meshwork. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 897118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.J.; Xu, Y.L.; Yang, Y.Q.; Bing, Y.W.; Zhao, Y.X. Vitamin D receptor regulates high-level glucose induced retinal ganglion cell damage through STAT3 pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 7509–7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Before Matching: 17,865 vs. 17,235 | After Matching: 11,855 vs. 11,855 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Patient Count | % of Cohort | Std. Diff. | Mean ± SD | Patient Count | % of Cohort | Std. Diff. | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age at Index | 58.2 ± 12.8 vs. 64.5 ± 11.1 | 17,856 vs. 17,230 | 100% vs. 100% | 0.522 | 61.9 ± 11.4 vs. 62.0 ± 11.5 | 11,855 vs. 11,855 | 100% vs. 100% | 0.007 |

| Female | 11,812 vs. 12,273 | 66.2% vs. 71.2% | 0.110 | 8163 vs. 8183 | 68.9% vs. 69.0% | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 5966 vs. 4774 | 33.4% vs. 27.7% | 0.124 | 3618 vs. 3593 | 30.5% vs. 30.3% | 0.005 | ||

| White | 8933 vs. 11,470 | 50.0% vs. 66.6% | 0.340 | 7048 vs. 7066 | 59.5% vs. 59.6% | 0.003 | ||

| Unknown Race | 1642 vs. 1466 | 9.2% vs. 8.5% | 0.024 | 1098 vs. 1124 | 9.3% vs. 9.5% | 0.008 | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 13,530 vs. 14,333 | 75.8% vs. 83.2% | 0.184 | 9604 vs. 9600 | 81.0% vs. 81.0% | 0.001 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2786 vs. 1203 | 15.6% vs. 7.0% | 0.275 | 1155 vs. 1132 | 9.7% vs. 9.5% | 0.007 | ||

| Black or African American | 5322 vs. 2577 | 29.8% vs. 15.0% | 0.362 | 2424 vs. 2429 | 20.4% vs. 20.5% | 0.001 | ||

| Asian | 954 vs. 1091 | 5.3% vs. 6.3% | 0.042 | 733 vs. 727 | 6.2% vs. 6.1% | 0.002 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Hypertensive diseases | 9770 vs. 9063 | 54.7% vs. 52.6% | 0.042 | 6199 vs. 6248 | 52.3% vs. 52.7% | 0.008 | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 2022 vs. 1774 | 11.3% vs. 10.3% | 0.033 | 1270 vs. 1276 | 10.7% vs. 10.8% | 0.002 | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1100 vs. 1062 | 6.2% vs. 6.2% | <0.001 | 703 vs. 716 | 5.9% vs. 6.0% | 0.005 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6408 vs. 4466 | 35.9% vs. 25.9% | 0.217 | 3506 vs. 3516 | 29.6% vs. 29.7% | 0.002 | ||

| Medication | ||||||||

| Antilipidemic agents | 6363 vs. 6230 | 35.6% vs. 36.2% | 0.011 | 4148 vs. 4154 | 35.0% vs. 35.0% | 0.001 | ||

| Diuretics | 5245 vs. 4219 | 29.4% vs. 24.5% | 0.110 | 3116 vs. 3143 | 26.3% vs. 26.5% | 0.005 | ||

| Beta blockers | 4645 vs. 4134 | 26.0% vs. 24.0% | 0.047 | 2925 vs. 2913 | 24.7% vs. 24.6% | 0.002 | ||

| ACE inhibitors | 4038 vs. 2980 | 22.6% vs. 17.3% | 0.133 | 2260 vs. 2287 | 19.1% vs. 19.3% | 0.006 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | 3666 vs. 3038 | 20.5% vs. 17.6% | 0.074 | 2194 vs. 2190 | 18.5% vs. 18.5% | 0.001 | ||

| Angiotensin II inhibitors | 2253 vs. 2321 | 12.6% vs. 13.5% | 0.025 | 1522 vs. 1549 | 12.8% vs. 13.1% | 0.007 | ||

| Blood glucose regulation agents | 5827 vs. 3906 | 32.6% vs. 22.7% | 0.224 | 3122 vs. 3094 | 26.3% vs. 26.1% | 0.005 | ||

| Laboratory (Blood test) | ||||||||

| Calcidiol | 19.6 ± 6.6 vs. 43.0 ± 12.6 | 16,545 vs. 16,156 | 92.7% vs. 93.8% | 2.331 | 20.4 ± 6.4 vs. 42.6 ± 12.7 | 10,877 vs. 11,081 | 91.8% vs. 93.5% | 2.206 |

| Creatinine | 1.1 ± 1.9 vs. 1.1 ± 2.6 | 15,726 vs. 15,290 | 88.1% vs. 88.7% | 0.022 | 1.0 ± 2.0 vs. 1.1 ± 2.9 | 10,364 vs. 10,389 | 87.4% vs. 87.6% | 0.024 |

| Urea nitrogen | 17.5 ± 11.5 vs. 17.9 ± 9.4 | 15,905 vs. 15,296 | 89.1% vs. 88.8% | 0.040 | 17.3 ± 10.1 vs. 17.8 ± 9.9 | 10,416 vs. 10,437 | 87.9% vs. 88.0% | 0.048 |

| Bicarbonate | 26.5 ± 3.1 vs. 26.9 ± 2.9 | 15,832 vs. 15,232 | 88.7% vs. 88.4% | 0.142 | 26.6 ± 3.0 vs. 26.8 ± 3.0 | 10,373 vs. 10,391 | 87.5% vs. 87.7% | 0.056 |

| Sodium | 139.2 ± 2.8 vs. 139.6 ± 2.9 | 15,891 vs. 15,287 | 89.0% vs. 88.7% | 0.117 | 139.4 ± 2.8 vs. 139.5 ± 2.8 | 10,413 vs. 10,433 | 87.8% vs. 88.0% | 0.042 |

| Potassium | 4.2 ± 0.4 vs. 4.2 ± 0.4 | 15,920 vs. 15,319 | 89.2% vs. 88.9% | 0.092 | 4.2 ± 0.4 vs. 4.2 ± 0.4 | 10,432 vs. 10,450 | 88.0% vs. 88.1% | 0.017 |

| Glucose | 121.1 ± 58.8 vs. 109.0 ± 39.4 | 15,802 vs. 15,191 | 88.5% vs. 88.2% | 0.243 | 114.1 ± 49.5 vs. 111.9 ± 43.4 | 10,346 vs. 10,381 | 87.3% vs. 87.6% | 0.046 |

| 0–60 mg/dL | 662 vs. 378 | 3.7% vs. 2.2% | 0.090 | 312 vs. 312 | 2.6% vs. 2.6% | <0.001 | ||

| 60–90 mg/dL | 6714 vs. 6348 | 37.6% vs. 36.8% | 0.016 | 4331 vs. 4309 | 36.5% vs. 36.3% | 0.004 | ||

| 90–120 mg/dL | 10,395 vs. 10,728 | 58.2% vs. 62.3% | 0.083 | 7121 vs. 7077 | 60.1% vs. 59.7% | 0.008 | ||

| 120–150 mg/dL | 5324 vs. 4065 | 29.8% vs. 23.6% | 0.141 | 3052 vs. 3116 | 25.7% vs. 26.3% | 0.012 | ||

| 150–180 mg/dL | 3673 vs. 2436 | 20.6% vs. 14.1% | 0.170 | 1984 vs. 1975 | 16.7% vs. 16.7% | 0.002 | ||

| Calcium | 9.3 ± 0.6 vs. 9.5 ± 0.5 | 15,883 vs. 15,374 | 89.0% vs. 89.2% | 0.237 | 9.4 ± 0.5 vs. 9.4 ± 0.5 | 10,426 vs. 10,470 | 87.9% vs. 88.3% | 0.076 |

| 0–8.50 mg/dL | 2417 vs. 1353 | 13.5% vs. 7.9% | 0.185 | 1126 vs. 1126 | 9.5% vs. 9.5% | <0.001 | ||

| 8.50–10 mg/dL | 14,686 vs. 13,981 | 82.2% vs. 81.1% | 0.029 | 9592 vs. 9609 | 80.9% vs. 81.1% | 0.004 | ||

| 10–11 mg/dL | 2943 vs. 3670 | 16.5% vs. 21.3% | 0.123 | 2201 vs. 2167 | 18.6% vs. 18.3% | 0.007 | ||

| 11–13 mg/dL | 258 vs. 228 | 1.4% vs. 1.3% | 0.010 | 163 vs. 158 | 1.4% vs. 1.3% | 0.004 | ||

| Magnesium | 2.0 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.3 | 3382 vs. 2834 | 18.9% vs. 16.4% | 0.063 | 2.0 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1986 vs. 2005 | 16.8% vs. 16.9% | 0.030 |

| Phosphate | 3.7 ± 0.9 vs. 3.5 ± 0.8 | 3984 vs. 3231 | 22.3% vs. 18.8% | 0.137 | 3.6 ± 0.8 vs. 3.5 ± 0.8 | 2312 vs. 2332 | 19.5% vs. 19.7% | 0.032 |

| Leukocytes | 8.9 ± 90.1 vs. 11.1 ± 139.5 | 12,301 vs. 11,251 | 68.9% vs. 65.3% | 0.018 | 9.2 ± 98.6 vs. 11.9 ± 150.5 | 7815 vs. 7842 | 65.9% vs. 66.1% | 0.021 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.1 ± 1.9 vs. 13.3 ± 1.6 | 14,411 vs. 13,486 | 80.7% vs. 78.3% | 0.143 | 13.2 ± 1.7 vs. 13.2 ± 1.7 | 9363 vs. 9353 | 79.0% vs. 78.9% | 0.038 |

| Hematocrit | 39.5 ± 5.2 vs. 40.2 ± 4.6 | 14,597 vs. 13,849 | 81.7% vs. 80.4% | 0.133 | 39.9 ± 4.9 vs. 40.1 ± 4.7 | 9532 vs. 9505 | 80.4% vs. 80.2% | 0.032 |

| Platelets | 245.2 ± 77.2 vs. 239.3 ± 69.5 | 14,326 vs. 13,551 | 80.2% vs. 78.6% | 0.080 | 242.2 ± 73.6 vs. 241.1 ± 70.9 | 9326 vs. 9291 | 78.7% vs. 78.4% | 0.015 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 26.4 ± 37.1 vs. 24.6 ± 27.8 | 14,560 vs. 14,129 | 81.5% vs. 82.0% | 0.054 | 25.2 ± 42.0 vs. 25.4 ± 32.4 | 9578 vs. 9584 | 80.8% vs. 80.8% | 0.006 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 26.0 ± 115.4 vs. 25.0 ± 28.7 | 14,460 vs. 14,027 | 81.0% vs. 81.4% | 0.012 | 25.9 ± 141.5 vs. 25.3 ± 33.9 | 9506 vs. 9500 | 80.2% vs. 80.1% | 0.006 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 84.4 ± 48.0 vs. 75.6 ± 33.5 | 14,176 vs. 13,677 | 79.4% vs. 79.4% | 0.215 | 80.0 ± 41.5 vs. 78.4 ± 35.4 | 9300 vs. 9283 | 78.4% vs. 78.3% | 0.042 |

| 0–50 U/L | 1674 vs. 2244 | 9.4% vs. 13.0% | 0.116 | 1293 vs. 1319 | 10.9% vs. 11.1% | 0.007 | ||

| 50–70 U/L | 5329 vs. 6081 | 29.8% vs. 35.3% | 0.116 | 3852 vs. 3810 | 32.5% vs. 32.1% | 0.008 | ||

| 70–90 U/L | 5765 vs. 5167 | 32.3% vs. 30.0% | 0.050 | 3673 vs. 3675 | 31.0% vs. 31.0% | <0.001 | ||

| 90–120 U/L | 4298 vs. 3069 | 24.1% vs. 17.8% | 0.154 | 2414 vs. 2422 | 20.4% vs. 20.4% | 0.002 | ||

| Bilirubin, total | 0.6 ± 0.5 vs. 0.6 ± 0.4 | 14,102 vs. 13,597 | 79.0% vs. 78.9% | 0.022 | 0.6 ± 0.4 vs. 0.6 ± 0.4 | 9248 vs. 9227 | 78.0% vs. 77.8% | 0.020 |

| Albumin | 4.0 ± 0.5 vs. 4.1 ± 0.4 | 14,137 vs. 13,649 | 79.2% vs. 79.2% | 0.221 | 4.0 ± 0.5 vs. 4.1 ± 0.4 | 9265 vs. 9280 | 78.2% vs. 78.3% | 0.031 |

| 0–3 g/dL | 1384 vs. 699 | 7.8% vs. 4.1% | 0.157 | 609 vs. 603 | 5.1% vs. 5.1% | 0.002 | ||

| 3–4 g/dL | 7964 vs. 6782 | 44.6% vs. 39.4% | 0.106 | 4822 vs. 4862 | 40.7% vs. 41.0% | 0.007 | ||

| 4–5 g/dL | 9636 vs. 10,386 | 54.0% vs. 60.3% | 0.128 | 6763 vs. 6810 | 57.0% vs. 57.4% | 0.008 | ||

| Total protein | 7.1 ± 0.7 vs. 7.0 ± 0.6 | 13,930 vs. 13,377 | 78.0% vs. 77.6% | 0.140 | 7.1 ± 0.7 vs. 7.1 ± 0.6 | 9111 vs. 9084 | 76.9% vs. 76.6% | 0.029 |

| Total Cholesterol | 183.3 ± 50.0 vs. 180.1 ± 46.5 | 12,806 vs. 12,588 | 71.7% vs. 73.1% | 0.066 | 182.2 ± 48.7 vs. 181.1 ± 47.7 | 8503 vs. 8416 | 71.7% vs. 71.0% | 0.023 |

| 0–150 mg/dL | 3175 vs. 3200 | 17.8% vs. 18.6% | 0.021 | 2132 vs. 2138 | 18.0% vs. 18.0% | 0.001 | ||

| 150–200 mg/dL | 6276 vs. 6415 | 35.1% vs. 37.2% | 0.043 | 4220 vs. 4148 | 35.6% vs. 35.0% | 0.013 | ||

| 200–300 mg/dL | 4969 vs. 4554 | 27.8% vs. 26.4% | 0.031 | 3166 vs. 3210 | 26.7% vs. 27.1% | 0.008 | ||

| Cholesterol in LDL | 105.3 ± 39.8 vs. 100.3 ± 36.4 | 12,698 vs. 12,533 | 71.1% vs. 72.7% | 0.132 | 103.6 ± 38.5 vs. 102.2 ± 37.8 | 8461 vs. 8367 | 71.4% vs. 70.6% | 0.037 |

| 0–50 mg/dL | 937 vs. 864 | 5.2% vs. 5.0% | 0.011 | 600 vs. 610 | 5.1% vs. 5.1% | 0.004 | ||

| 50–100 mg/dL | 5595 vs. 6306 | 31.3% vs. 36.6% | 0.111 | 3946 vs. 3942 | 33.3% vs. 33.3% | 0.001 | ||

| 100–150 mg/dL | 6043 vs. 5746 | 33.8% vs. 33.3% | 0.010 | 3959 vs. 3908 | 33.4% vs. 33.0% | 0.009 | ||

| Cholesterol in HDL | 50.6 ± 18.4 vs. 55.2 ± 21.2 | 12,794 vs. 12,592 | 71.7% vs. 73.1% | 0.235 | 52.7 ± 19.2 vs. 53.2 ± 20.3 | 8500 vs. 8423 | 71.7% vs. 71.1% | 0.027 |

| 0–40 mg/dL | 3634 vs. 2615 | 20.4% vs. 15.2% | 0.136 | 2003 vs. 2027 | 16.9% vs. 17.1% | 0.005 | ||

| 40–60 mg/dL | 6827 vs. 6203 | 38.2% vs. 36.0% | 0.046 | 4401 vs. 4383 | 37.1% vs. 37.0% | 0.003 | ||

| 60–80 mg/dL | 2940 vs. 3841 | 16.5% vs. 22.3% | 0.148 | 2295 vs. 2288 | 19.4% vs. 19.3% | 0.001 | ||

| Triglyceride | 141.6 ± 116.1 vs. 119.3 ± 83.6 | 12,575 vs. 12,348 | 70.4% vs. 71.7% | 0.221 | 131.2 ± 98.7 vs. 126.1 ± 91.7 | 8386 vs. 8254 | 70.7% vs. 69.6% | 0.053 |

| 0–100 mg/dL | 5349 vs. 6408 | 30.0% vs. 37.2% | 0.154 | 3940 vs. 3900 | 33.2% vs. 32.9% | 0.007 | ||

| 100–150 mg/dL | 4347 vs. 4258 | 24.3% vs. 24.7% | 0.009 | 2867 vs. 2874 | 24.2% vs. 24.2% | 0.001 | ||

| 150–200 mg/dL | 2474 vs. 2130 | 13.9% vs. 12.4% | 0.044 | 1537 vs. 1557 | 13.0% vs. 13.1% | 0.005 | ||

| 200–300 mg/dL | 1912 vs. 1390 | 10.7% vs. 8.1% | 0.091 | 1075 vs. 1086 | 9.1% vs. 9.2% | 0.003 | ||

| Hemoglobin A1c | 6.9 ± 2.0 vs. 6.3 ± 1.5 | 9969 vs. 8215 | 55.8% vs. 47.7% | 0.314 | 6.5 ± 1.7 vs. 6.4 ± 1.6 | 6032 vs. 5914 | 50.9% vs. 49.9% | 0.050 |

| 0–5% | 555 vs. 487 | 3.1% vs. 2.8% | 0.017 | 352 vs. 347 | 3.0% vs. 2.9% | 0.002 | ||

| 5–6% | 4214 vs. 4342 | 23.6% vs. 25.2% | 0.037 | 2885 vs. 2874 | 24.3% vs. 24.2% | 0.002 | ||

| 6–7% | 3622 vs. 3194 | 20.3% vs. 18.5% | 0.044 | 2324 vs. 2366 | 19.6% vs. 20.0% | 0.009 | ||

| 7–8% | 2091 vs. 1545 | 11.7% vs. 9.0% | 0.090 | 1231 vs. 1224 | 10.4% vs. 10.3% | 0.002 | ||

| 8–9% | 1328 vs. 805 | 7.4% vs. 4.7% | 0.116 | 701 vs. 684 | 5.9% vs. 5.8% | 0.006 | ||

| ≥9% | 1842 vs. 656 | 10.3% vs. 3.8% | 0.256 | 609 vs. 604 | 5.1% vs. 5.1% | 0.002 | ||

| Iron | 70.6 ± 41.5 vs. 77.7 ± 36.9 | 3116 vs. 2431 | 17.5% vs. 14.1% | 0.180 | 75.3 ± 41.5 vs. 75.1 ± 37.1 | 1796 vs. 1802 | 15.1% vs. 15.2% | 0.005 |

| 0–50 µg/dL | 1219 vs. 673 | 6.8% vs. 3.9% | 0.130 | 565 vs. 566 | 4.8% vs. 4.8% | <0.001 | ||

| 50–100 µg/dL | 1770 vs. 1475 | 9.9% vs. 8.6% | 0.047 | 1076 vs. 1071 | 9.1% vs. 9.0% | 0.001 | ||

| 100–200 µg/dL | 606 vs. 634 | 3.4% vs. 3.7% | 0.015 | 419 vs. 441 | 3.5% vs. 3.7% | 0.010 | ||

| Ferritin | 245.7 ± 547.5 vs. 201.2 ± 551.2 | 3254 vs. 2474 | 18.2% vs. 14.4% | 0.081 | 213.2 ± 427.3 vs. 202.3 ± 485.9 | 1871 vs. 1882 | 15.8% vs. 15.9% | 0.024 |

| CRP | 18.4 ± 37.8 vs. 11.6 ± 28.5 | 2156 vs. 2050 | 12.1% vs. 11.9% | 0.203 | 13.9 ± 31.2 vs. 13.6 ± 31.4 | 1354 vs. 1363 | 11.4% vs. 11.5% | 0.009 |

| 0–10 mg/L | 1486 vs. 1657 | 8.3% vs. 9.6% | 0.045 | 1040 vs. 1049 | 8.8% vs. 8.8% | 0.003 | ||

| 10–20 mg/L | 488 vs. 327 | 2.7% vs. 1.9% | 0.056 | 268 vs. 257 | 2.3% vs. 2.2% | 0.006 | ||

| 20–40 mg/L | 315 vs. 201 | 1.8% vs. 1.2% | 0.050 | 151 vs. 165 | 1.3% vs. 1.4% | 0.010 | ||

| Follow-Up | Outcomes | Cohorts | Patients in Cohort | Patients with Outcome | Survival Probability | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Log-Rank Test, p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | All-cause mortality | VDD | 10,033 | 214 | 97.82% | 1.306 | (1.066–1.600) | 0.010 |

| VDA | 10,012 | 165 | 98.33% | |||||

| 3 years | VDD | 10,029 | 512 | 94.61% | 1.132 | (0.998–1.284) | 0.053 | |

| VDA | 10,014 | 460 | 95.19% | |||||

| 5 years | VDD | 11,040 | 833 | 91.81% | 1.104 | (1.001–1.217) | 0.048 | |

| VDA | 11,023 | 770 | 92.52% | |||||

| 1 year | MACE | VDD | 7286 | 550 | 92.29% | 1.278 | (1.127–1.449) | <0.001 |

| VDA | 7320 | 439 | 93.90% | |||||

| 3 years | VDD | 7258 | 1221 | 82.27% | 1.172 | (1.080–1.272) | <0.001 | |

| VDA | 7318 | 1080 | 84.54% | |||||

| 5 years | VDD | 7984 | 1890 | 74.42% | 1.151 | (1.078–1.229) | <0.001 | |

| VDA | 8002 | 1703 | 77.20% | |||||

| 1 year | AKI | VDD | 9762 | 287 | 97.00% | 1.288 | (1.081–1.534) | 0.004 |

| VDA | 9721 | 224 | 97.66% | |||||

| 3 years | VDD | 9768 | 638 | 93.10% | 1.113 | (0.995–1.246) | 0.061 | |

| VDA | 9721 | 581 | 93.74% | |||||

| 5 years | VDD | 10,683 | 1036 | 89.42% | 1.154 | (1.056–1.261) | 0.002 | |

| VDA | 10,622 | 915 | 90.74% | |||||

| 1 year | eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | VDD | 6745 | 473 | 92.85% | 0.999 | (0.879–1.137) | 0.993 |

| VDA | 6458 | 455 | 92.85% | |||||

| 3 years | VDD | 6759 | 1083 | 83.09% | 1.050 | (0.963–1.144) | 0.271 | |

| VDA | 6456 | 995 | 83.93% | |||||

| 5 years | VDD | 7284 | 1581 | 76.59% | 0.972 | (0.907–1.042) | 0.428 | |

| VDA | 6997 | 1576 | 75.97% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wen, S.-S.; Lu, C.-L.; Tsai, M.-L.; Hour, A.-L.; Lu, K.-C. Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Systemic Outcomes in Patients with Glaucoma: A Real-World Cohort Study. Nutrients 2026, 18, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020261

Wen S-S, Lu C-L, Tsai M-L, Hour A-L, Lu K-C. Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Systemic Outcomes in Patients with Glaucoma: A Real-World Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020261

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Shan-Shy, Chien-Lin Lu, Ming-Ling Tsai, Ai-Ling Hour, and Kuo-Cheng Lu. 2026. "Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Systemic Outcomes in Patients with Glaucoma: A Real-World Cohort Study" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020261

APA StyleWen, S.-S., Lu, C.-L., Tsai, M.-L., Hour, A.-L., & Lu, K.-C. (2026). Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Systemic Outcomes in Patients with Glaucoma: A Real-World Cohort Study. Nutrients, 18(2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020261