About Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity Interventions: A Focus on Energy Balance and Body-Weight Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. What Is the Potential Magnitude of Individual Differences in Weight Loss Under Well-Controlled Living Conditions?

3. What Is the Proportion of Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity?

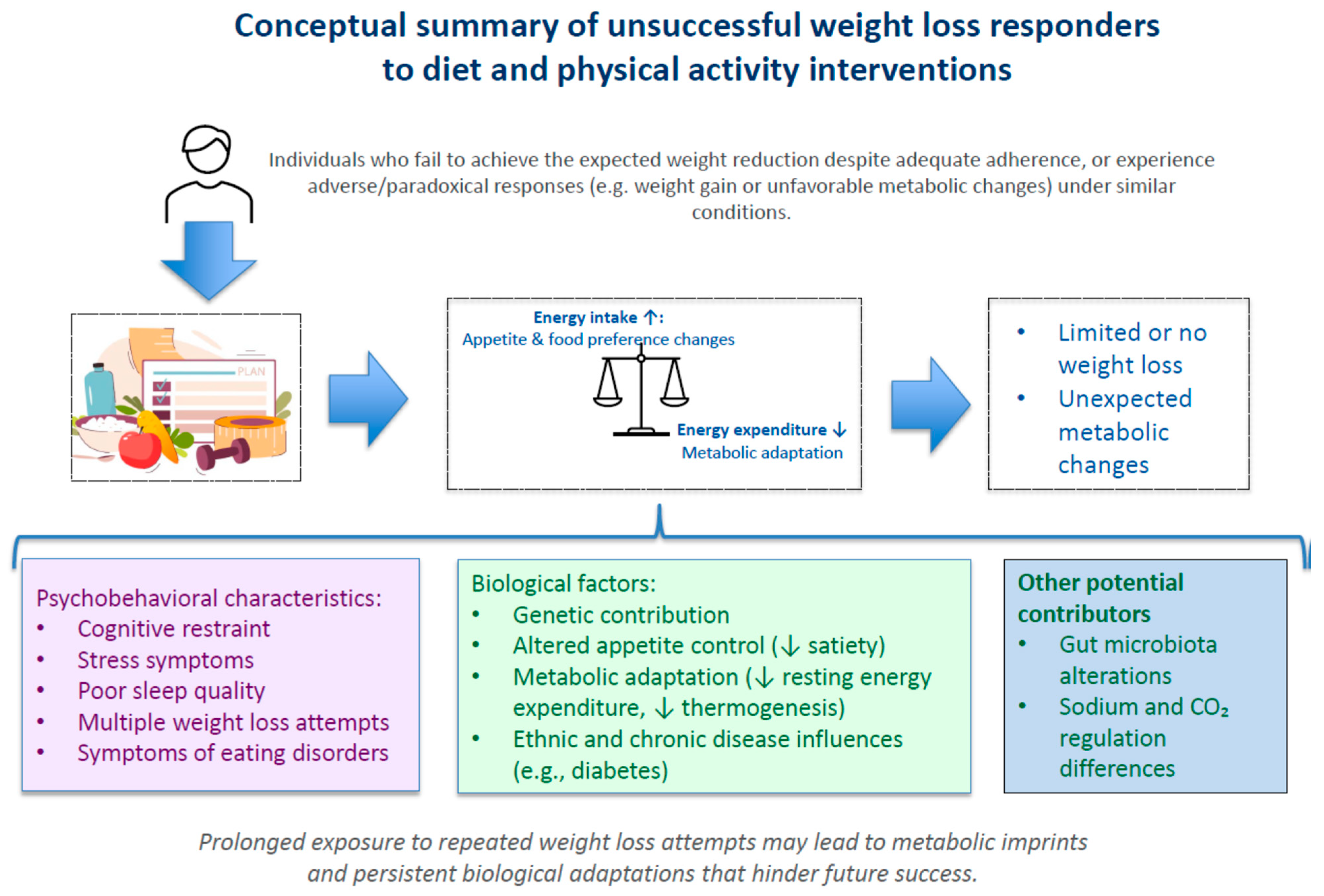

4. What Is the Profile of Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity?

5. Does the Case of Unsuccessful Responders Reflect an Incomplete Understanding of Obesity Determinants?

6. Can Successful Responders Become Unsuccessful Maintainers?

7. What Should Be the Obesity Management of Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity?

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A.; Despres, J.P.; Theriault, G.; Nadeau, A.; Lupien, P.J.; Moorjani, S.; Prudhomme, D.; Fournier, G. The response to exercise with constant energy intake in identical twins. Obes. Res. 1994, 2, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A.; Despres, J.P.; Nadeau, A.; Lupien, P.J.; Theriault, G.; Dussault, J.; Moorjani, S.; Pinault, S.; Fournier, G. The response to long-term overfeeding in identical twins. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, S.; Kim, S.; Bersamin, A.; King, A.C.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary adherence and weight loss success among overweight women: Results from the A TO Z weight loss study. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ard, J.D.; Lewis, K.H.; Cohen, S.S.; Rothberg, A.E.; Coburn, S.L.; Loper, J.; Matarese, L.; Pories, W.J.; Periman, S. Differences in treatment response to a total diet replacement intervention versus a food-based intervention: A secondary analysis of the OPTIWIN trial. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Carey, V.J.; Smith, S.R.; Ryan, D.H.; Anton, S.D.; McManus, K.; Champagne, C.M.; Bishop, L.M.; Laranjo, N.; et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, C.; Blair, S.N.; Church, T.S.; Earnest, C.P.; Hagberg, J.M.; Hakkinen, K.; Jenkins, N.T.; Karavirta, L.; Kraus, W.E.; Leon, A.S.; et al. Adverse metabolic response to regular exercise: Is it a rare or common occurrence? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzynski, M.A.; Rice, T.K.; Despres, J.P.; Perusse, L.; Tremblay, A.; Stanforth, P.R.; Tchernof, A.; Barber, J.L.; Falciani, F.; Clish, C.; et al. The HERITAGE Family Study: A Review of the Effects of Exercise Training on Cardiometabolic Health, with Insights into Molecular Transducers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, S1–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelholm, M.; Larsen, T.M.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.; Macdonald, I.; Martinez, J.A.; Boyadjieva, N.; Poppitt, S.; Schlicht, W.; Stratton, G.; Sundvall, J.; et al. PREVIEW: Prevention of Diabetes through Lifestyle Intervention and Population Studies in Europe and around the World. Design, Methods, and Baseline Participant Description of an Adult Cohort Enrolled into a Three-Year Randomised Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raben, A.; Vestentoft, P.S.; Brand-Miller, J.; Jalo, E.; Drummen, M.; Simpson, L.; Martinez, J.A.; Handjieva-Darlenska, T.; Stratton, G.; Huttunen-Lenz, M.; et al. The PREVIEW intervention study: Results from a 3-year randomized 2 x 2 factorial multinational trial investigating the role of protein, glycaemic index and physical activity for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A.; Fogelholm, M.; Jalo, E.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Adam, T.C.; Huttunen-Lenz, M.; Stratton, G.; Lam, T.; Handjieva-Darlenska, T.; Handjiev, S.; et al. What Is the Profile of Overweight Individuals Who Are Unsuccessful Responders to a Low-Energy Diet? A PREVIEW Sub-study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 707682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, A.; Lepage, C.; Panahi, S.; Couture, C.; Drapeau, V. Adaptations to a diet-based weight-reducing programme in obese women resistant to weight loss. Clin. Obes. 2015, 5, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Couture, E.; Filion, M.J.; Boukari, R.; Jeejeebhoy, K.; Dhaliwal, R.; Brauer, P.; Royall, D.; Mutch, D.M.; Klein, D.; Tremblay, A.; et al. Relationship between Cardiometabolic Factors and the Response of Blood Pressure to a One-Year Primary Care Lifestyle Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome Patients. Metabolites 2022, 12, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, M.R.; Horwitz, B.A.; Stern, J.S. Effect of adrenalectomy and glucocorticoid replacement on development of obesity. Am. J. Physiol. 1986, 250, R595–R607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuyama, K.; Himms-Hagen, J. Adrenalectomy prevents obesity in glutamate-treated mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1989, 257, E139–E144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buemann, B.; Vohl, M.C.; Chagnon, M.; Chagnon, Y.C.; Gagnon, J.; Perusse, L.; Dionne, F.; Despres, J.P.; Tremblay, A.; Nadeau, A.; et al. Abdominal visceral fat is associated with a BclI restriction fragment length polymorphism at the glucocorticoid receptor gene locus. Obes. Res. 1997, 5, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A.; Bouchard, L.; Bouchard, C.; Despres, J.P.; Drapeau, V.; Perusse, L. Long-term adiposity changes are related to a glucocorticoid receptor polymorphism in young females. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 3141–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, K.; Leproult, R.; L’Hermite-Baleriaux, M.; Copinschi, G.; Penev, P.D.; Van Cauter, E. Leptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: Relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5762–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Despres, J.P.; Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin levels and increased adiposity: Results from the Quebec family study. Obesity 2007, 15, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Doucet, E.; Tremblay, A. Obesity: A disease or a biological adaptation? An update. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Drapeau, V.; Tremblay, A.; Provencher, V.; Bouchard, C.; Perusse, L. The role of eating behavior traits in mediating genetic susceptibility to obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Bertrand, C.; Llewellyn, C.; Couture, C.; Labonte, M.E.; Tremblay, A.; Bouchard, C.; Drapeau, V.; Perusse, L. Dietary Mediators of the Genetic Susceptibility to Obesity-Results from the Quebec Family Study. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, A.; Perusse, L.; Bertrand, C.; Jacob, R.; Couture, C.; Drapeau, V. Effects of sodium intake and cardiorespiratory fitness on body composition and genetic susceptibility to obesity: Results from the Quebec Family Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersoug, L.G.; Sjodin, A.; Astrup, A. A proposed potential role for increasing atmospheric CO2 as a promoter of weight gain and obesity. Nutr. Diabetes 2012, 2, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldebrant, D.J.; Yonker, C.R.; Jessop, P.G.; Phan, L. Reversible uptake of COS, CS2, and SO2: Ionic liquids with O-alkylxanthate, O-alkylthiocarbonyl, and O-alkylsulfite anions. Chemistry 2009, 15, 7619–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpertz, R.; Le, D.S.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Trinidad, C.; Bogardus, C.; Gordon, J.I.; Krakoff, J. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Backhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11070–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadooka, Y.; Sato, M.; Imaizumi, K.; Ogawa, A.; Ikuyama, K.; Akai, Y.; Okano, M.; Kagoshima, M.; Tsuchida, T. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.; Darimont, C.; Drapeau, V.; Emady-Azar, S.; Lepage, M.; Rezzonico, E.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Berger, B.; Philippe, L.; Ammon-Zuffrey, C.; et al. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus CGMCC1.3724 supplementation on weight loss and maintenance in obese men and women. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.S.; Brunelle, L.; Pilon, G.; Cautela, B.G.; Tompkins, T.A.; Drapeau, V.; Marette, A.; Tremblay, A. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus HA-114 improves eating behaviors and mood-related factors in adults with overweight during weight loss: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.; Darimont, C.; Panahi, S.; Drapeau, V.; Marette, A.; Taylor, V.H.; Dore, J.; Tremblay, A. Effects of a Diet-Based Weight-Reducing Program with Probiotic Supplementation on Satiety Efficiency, Eating Behaviour Traits, and Psychosocial Behaviours in Obese Individuals. Nutrients 2017, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W.; Konz, E.C.; Frederich, R.C.; Wood, C.L. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, S.; Roy, B.; Tremblay, A. A case study on energy balance during an expedition through Greenland. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1996, 20, 493–495. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, A.; Major, G.; Doucet, E.; Trayhurn, P.; Astrup, A. Role of adaptive thermogenesis in unsuccessful weight-loss intervention. Future Lipidol. 2007, 2, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fothergill, E.; Guo, J.; Howard, L.; Kerns, J.C.; Knuth, N.D.; Brychta, R.; Chen, K.Y.; Skarulis, M.C.; Walter, M.; Walter, P.J.; et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after "The Biggest Loser" competition. Obesity 2016, 24, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailly, M.; Isacco, L.; Dutheil, F.; Courteix, D.; Lesourd, B.; Chapier, R.; Obert, P.; Walther, G.; Bagheri, R.; Vinet, A.; et al. Initial and evolutionary profile of adverse responders to an intensive weight loss intervention: The RESOLVE Study. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2025, 65, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baak, M.A.; Mariman, E.C.M. Mechanisms of weight regain after weight loss—The role of adipose tissue. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbeault, P.; Findlay, C.S.; Robidoux, M.A.; Haman, F.; Blais, J.M.; Tremblay, A.; Springthorpe, S.; Pal, S.; Seabert, T.; Krummel, E.M.; et al. Dysregulation of cytokine response in Canadian First Nations communities: Is there an association with persistent organic pollutant levels? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle-Kampczyk, U.; Gebauer, S.; Haange, S.B.; Schubert, K.; Kern, M.; Moulla, Y.; Dietrich, A.; Schon, M.R.; Kloting, N.; von Bergen, M.; et al. Accumulation of distinct persistent organic pollutants is associated with adipose tissue inflammation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 142458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, C.; Doucet, E.; Imbeault, P.; Tremblay, A. Associations between weight loss-induced changes in plasma organochlorine concentrations, serum T(3) concentration, and resting metabolic rate. Toxicol. Sci. 2002, 67, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A.; Pelletier, C.; Doucet, E.; Imbeault, P. Thermogenesis and weight loss in obese individuals: A primary association with organochlorine pollution. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2004, 28, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbeault, P.; Tremblay, A.; Simoneau, J.A.; Joanisse, D.R. Weight loss-induced rise in plasma pollutant is associated with reduced skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 282, E574–E579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Leblanc, C.; Perusse, L.; Despres, J.P.; Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A. Risk factors for adult overweight and obesity in the Quebec Family Study: Have we been barking up the wrong tree? Obesity 2009, 17, 1964–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G.D.; Wadden, T.A.; Vogt, R.A.; Brewer, G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tremblay, A.; Jacob, R.; Pérusse, L.; Drapeau, V. About Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity Interventions: A Focus on Energy Balance and Body-Weight Loss. Nutrients 2026, 18, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020195

Tremblay A, Jacob R, Pérusse L, Drapeau V. About Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity Interventions: A Focus on Energy Balance and Body-Weight Loss. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020195

Chicago/Turabian StyleTremblay, Angelo, Raphaëlle Jacob, Louis Pérusse, and Vicky Drapeau. 2026. "About Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity Interventions: A Focus on Energy Balance and Body-Weight Loss" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020195

APA StyleTremblay, A., Jacob, R., Pérusse, L., & Drapeau, V. (2026). About Unsuccessful Responders to Diet and Physical Activity Interventions: A Focus on Energy Balance and Body-Weight Loss. Nutrients, 18(2), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020195