The Immune Mind: Linking Dietary Patterns, Microbiota, and Psychological Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

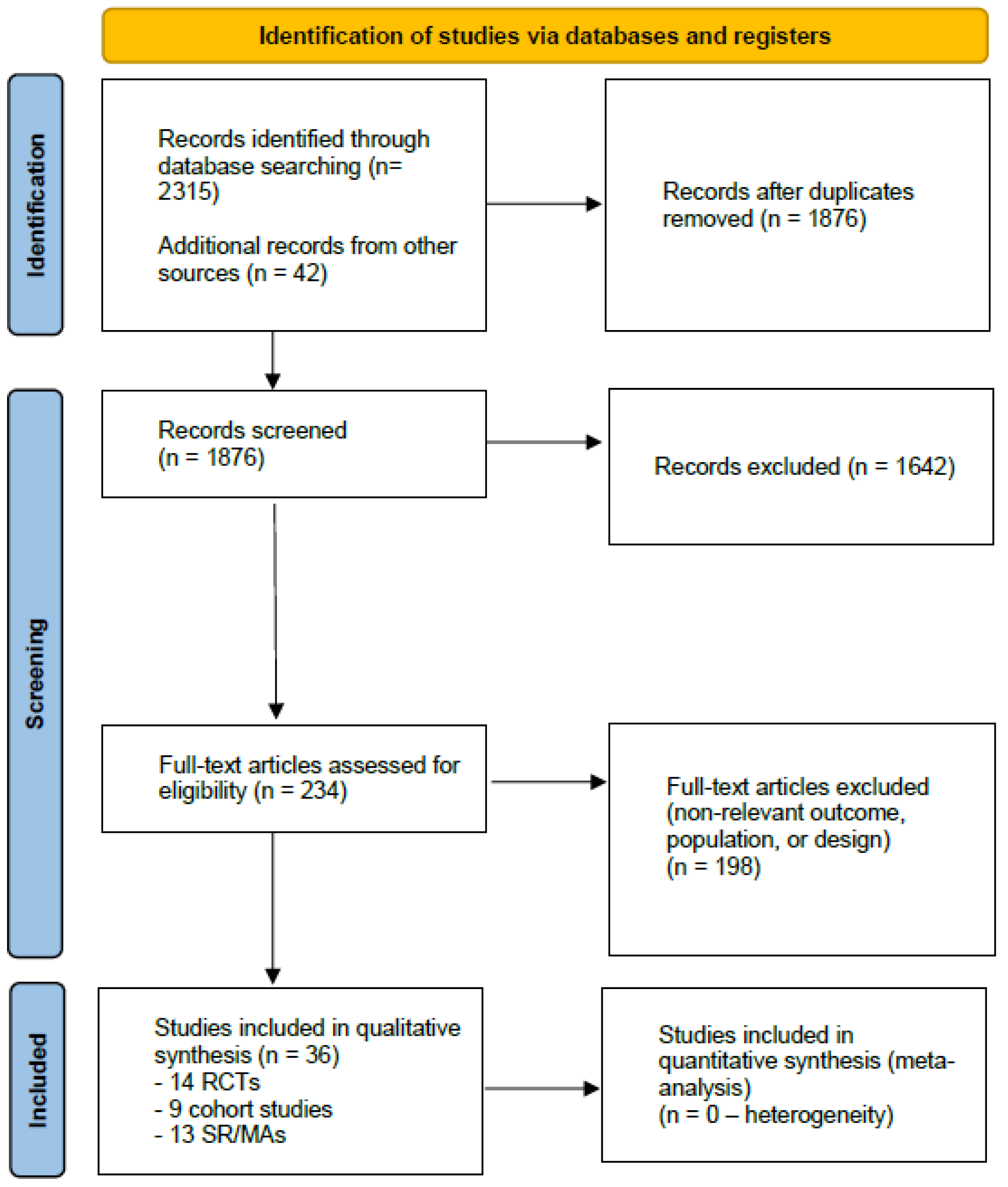

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Reporting

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Mediterranean-Style Diet (MD) Interventions and Depressive Outcomes

3.2. Ultra-Processed Food (UPF) and Common Mental Disorders

3.3. Psychobiotics (Probiotics/Prebiotics) for Depression/Anxiety

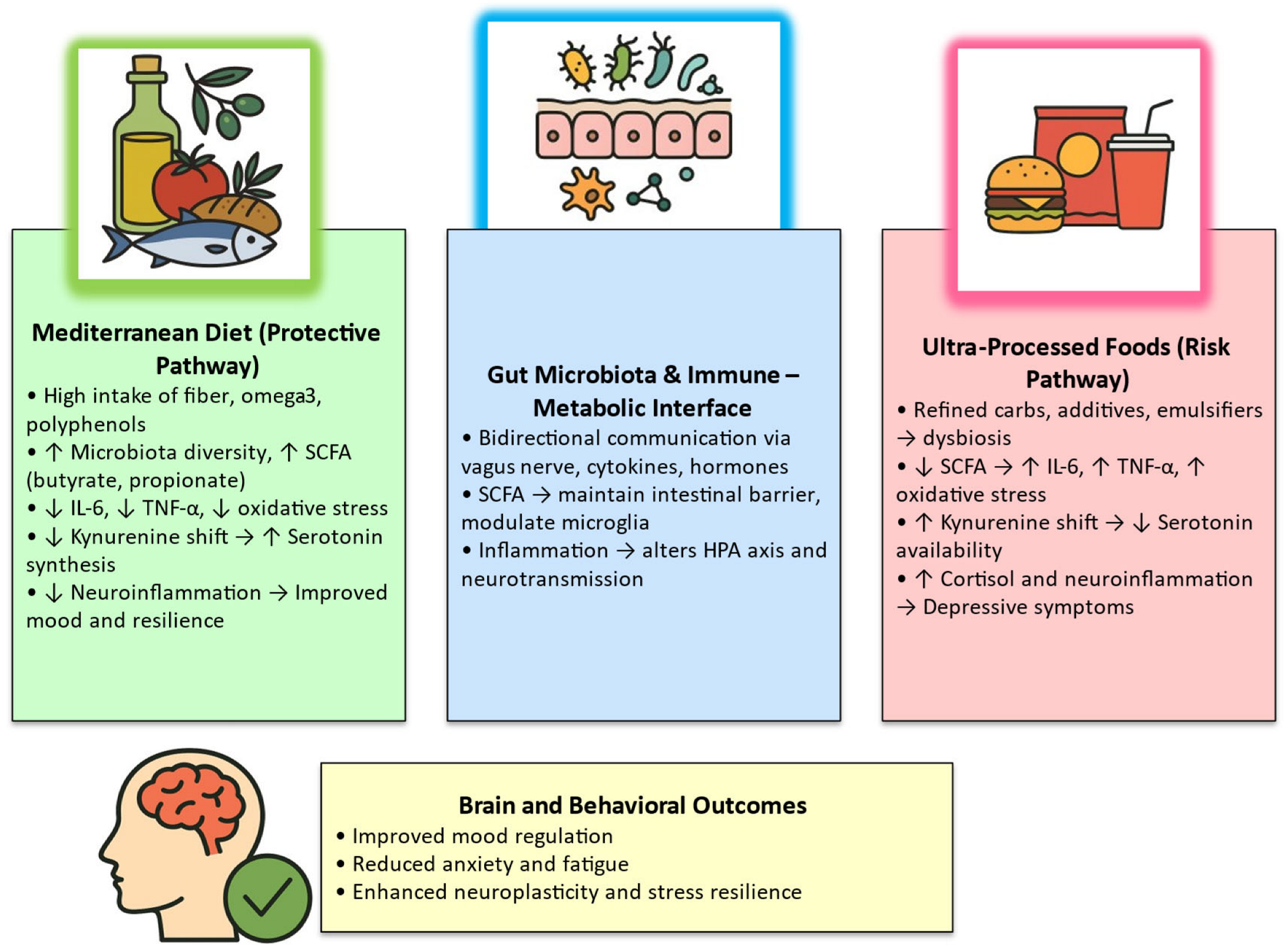

3.4. Integrative Mechanistic Overview

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (axis) |

| IDO | Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder |

| MD | Mediterranean diet |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acids |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| UPF | Ultra-processed food |

References

- Firth, J.; Marx, W.; Dash, S.; Carney, R.; Teasdale, S.B.; Solmi, M.; Stubbs, B.; Schuch, F.B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Jacka, F.; et al. The Effects of Dietary Improvement on Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Liu, M.; Zhao, L.; Hébert, J.R.; Steck, S.E.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Dietary Inflammatory Potential, Inflammation-Related Lifestyle Factors, and Incident Anxiety Disorders: A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, G.; Rossi, S.; Sfratta, G.; Traversi, G.; Lisci, F.M.; Anesini, M.B.; Pola, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gaetani, E.; Mazza, M. Gut Microbiota: A New Challenge in Mood Disorder Research. Life 2025, 15, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.C.; Olson, C.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, G.; Mazza, M.; Lisci, F.M.; Ciliberto, M.; Traversi, G.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; De Berardis, D.; Laterza, L.; Sani, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Psychoneuroimmunological Insights. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Cheng, X.; Zhong, S.; Liu, C.; Jolkkonen, J.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, C. Communications Between Peripheral and the Brain-Resident Immune System in Neuronal Regeneration After Stroke. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles-Colomer, M.; Falony, G.; Darzi, Y.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Wang, J.; Tito, R.Y.; Schiweck, C.; Kurilshikov, A.; Joossens, M.; Wijmenga, C.; et al. The Neuroactive Potential of the Human Gut Microbiota in Quality of Life and Depression. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radkhah, N.; Rasouli, A.; Majnouni, A.; Eskandari, E.; Parastouei, K. The effect of Mediterranean diet instructions on depression, anxiety, stress, and anthropometric indices: A randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Jiménez-López, E.; Núñez de Arenas-Arroyo, S.; Saz-Lara, A.; Díaz-Goñi, V.; Mesas, A.E. The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet on Alleviating Depressive Symptoms in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyrolle, Q.; Prado-Perez, L.; Layé, S. The Gut-Derived Metabolites as Mediators of the Effect of Healthy Nutrition on the Brain. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1155533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuthpongtorn, C.; Nguyen, L.H.; Okereke, O.I.; Wang, D.D.; Song, M.; Chan, A.T.; Mehta, R.S. Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2334770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaffi, J.; Mancarella, L.; Ripamonti, C.; Brusi, V.; Pignatti, F.; Lisi, L.; Ursini, F. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, F.E.C.; Lizcano Martinez, S.; Liscano, Y. Effectiveness of Psychobiotics in the Treatment of Psychiatric and Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.; Kirk, M.; Zhu, S.; Dong, X.; Gao, M. Effects of Prebiotics and Probiotics on Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in Clinically Diagnosed Samples: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e1504–e1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lyu, Q.; Huang, L.; Lou, Y.; Wang, L. Gut-brain axis and depression: Focus on the amino acid and short-chain fatty acid metabolism. Behav. Pharmacol. 2025, 36, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J.; Huang, X.F.; Newell, K.A. The Kynurenine Pathway in Major Depression: What We Know and Where to Next. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathomas, F.; Murrough, J.W.; Nestler, E.J.; Han, M.H.; Russo, S.J. Neurobiology of Resilience: Interface Between Mind and Body. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 86, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, G.; Bachtel, G.; Sugden, S.G. Gut Microbiota, Nutrition, and Mental Health. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1337889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, G.; Traversi, G.; Gaetani, E.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mazza, M. Gut Microbiota in Women: The Secret of Psychological and Physical Well-Being. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 5945–5952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, F.; Salari-Moghaddam, A.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Mediterranean Diet and Depression: Reanalysis of a Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 81, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassale, C.; Batty, G.D.; Baghdadli, A.; Jacka, F.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Akbaraly, T. Healthy Dietary Indices and Risk of Depressive Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 965–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Sancassiani, F.; Contu, M.P.; Latorre, M.; Di Salvatore, M.; Fornaro, M.; Bhugra, D. Mediterranean Diet and its Benefits on Health and Mental Health: A Literature Review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2020, 16, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheibani, M.; Shayan, M.; Khalilzadeh, M.; Soltani, Z.E.; Jafari-Sabet, M.; Ghasemi, M.; Dehpour, A.R. Kynurenine pathway and its role in neurologic, psychiatric, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 10409–10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N. Nutritional Psychiatry: Where to Next? eBioMedicine 2017, 17, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Exposure and Adverse Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Epidemiological Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, H.; Head, J.; Jacka, F.N.; Lane, M.M.; Kivimäki, M.; Akbaraly, T. Association between ultra-processed foods and recurrence of depressive symptoms: The Whitehall II cohort study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Song, R.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. Effects of ultra-processed foods on the microbiota-gut-brain axis: The bread-and-butter issue. Food Res. Int. 2023, 167, 112730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruohan, Z.; Ruting, W.; Hongxi, W.; Zhenjin, H.; Jiale, L.; Rongxin, Z.; Feng, J.; Yuanbo, S. Gut microbiota as a novel target for treating anxiety and depression: From mechanisms to multimodal interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1664800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, M.; Arancibia, M.; Moran-Kneer, J.; Manterola, M. Ultraprocessed Foods and Neuropsychiatric Outcomes: Putative Mechanisms. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu, A.; Alvarado-Gamarra, G.; Cornejo, R.; Curi-Quinto, K.; Díaz-Parra, C.D.P.; Rojas-Limache, G.; Lanata, C.F. Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption and Health-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1421728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertaş Öztürk, Y.; Uzdil, Z. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption Is Linked to Quality of Life and Mental Distress among University Students. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menni, A.E.; Theodorou, H.; Tzikos, G.; Theodorou, I.M.; Semertzidou, E.; Stelmach, V.; Shrewsbury, A.D.; Stavrou, G.; Kotzampassi, K. Rewiring Mood: Precision Psychobiotics as Adjunct or Stand-Alone Therapy in Depression Using Insights from 19 Randomized Controlled Trials in Adults. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Erdoğan Kaya, A.; Eskin, F. Bibliometric analysis of scientific outputs on psychobiotics: Strengthening the food and mood connection. Medicine 2024, 103, e39238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Asghar, T.; Hameed, H.; Din, A.M.; Siddique, A.; Younas, S.; Mohi Ud Din, M.; Ara, R. The psychobiotic revolution: Comprehending the optimistic role of gut microbiota on gut-brain axis during neurological and Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuigunov, D.; Sinyavskiy, Y.; Nurgozhin, T.; Zholdassova, Z.; Smagul, G.; Omarov, Y.; Dolmatova, O.; Yeshmanova, A.; Omarova, I. Precision Nutrition and Gut-Brain Axis Modulation in the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.M.; Yang, M.F.; Kong, C.; Luo, D.; Yue, N.N.; Zhao, H.L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.P.; Liang, Y.J.; Song, Y.; et al. Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis: Implications for the Links Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 13183–13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, G.; Anesini, M.B.; Milintenda, M.; Acanfora, M.; d’Abate, C.; Lisci, F.M.; Pirona, I.; Traversi, G.; Pola, R.; Gaetani, E.; et al. Discovering a new paradigm: Gut microbiota as a central modulator of sexual health. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2025, 16, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Feng, S.; Hao, Z.; Liu, H. A combination of potential psychobiotics alleviates anxiety and depression behaviors induced by chronic unpredictable mild stress. NPJ Biofilm. Microbiomes 2025, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal Abidin, Z.; Hein, Z.M.; Che Mohd Nassir, C.M.N.; Shari, N.; Che Ramli, M.D. Pharmacological modulation of the gut-brain axis: Psychobiotics in focus for depression therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1665419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, H.; Ju, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and depression: Deep insight into biological mechanisms and potential applications. Gen. Psychiatr. 2024, 37, e101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkouris, E.; Mavroudi, T.; Miliotas, D.; Tsiptsios, D.; Serdari, A.; Christidi, F.; Doskas, T.K.; Mueller, C.; Tsamakis, K. Probiotics’ Effects in the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression: A Comprehensive Review of 2014–2023 Clinical Trials. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliu, O. The current state of research for psychobiotics use in the management of psychiatric disorders—A systematic literature review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1074736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, P.; De Lorenzi, F.; Gędek, A.; Strater, C.; Popescu, E.; Ortuño, F.; Van Der Does, W.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Molendijk, M.L. Diet quality and depression risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 382, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhal, M.M.; Yassin, L.K.; Alyaqoubi, R.; Saeed, S.; Alderei, A.; Alhammadi, A.; Alshehhi, M.; Almehairbi, A.; Al Houqani, S.; BaniYas, S.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Neurological Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Life 2024, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltensperger, R.; Neher, J.; Böhm, L.; Mueller-Stierlin, A.S. Mapping the Scientific Research on Nutrition and Mental Health: A Bibliometric Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, C.; Wang, J.; Tang, B.; Cao, J.; Hu, X.; Zhao, X.; Feng, C. Association between gut microbiota and anxiety disorders: A bidirectional two-sample mendelian randomization study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, A.; Lingrand, L.; Maillard, M.; Feuz, B.; Tompkins, T.A. The effects of psychobiotics on the microbiota-gut-brain axis in early-life stress and neuropsychiatric disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 105, 110142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, A.; Maciak, K.; Bliźniewska-Kowalska, K.; Gałecka, M.; Kobierecka, W.; Saluk, J. The Power of Psychobiotics in Depression: A Modern Approach through the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parletta, N.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Cho, J.; Wilson, A.; Bogomolova, S.; Villani, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Niyonsenga, T.; Blunden, S.; Meyer, B.; et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Lane, M.; Hockey, M.; Aslam, H.; Berk, M.; Walder, K.; Borsini, A.; Firth, J.; Pariante, C.M.; Berding, K.; et al. Diet and depression: Exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, Y.; Lucas, G.; Iceta, S.; Boucekine, M.; Rahmati, M.; Berk, M.; Akbaraly, T.; Aouizerate, B.; Capuron, L.; Marx, W.; et al. Dietary patterns and major depression: Results from 15,262 participants (International ALIMENTAL Study). Nutrients 2025, 17, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Bonaccio, M.; Al-Qahtani, W.H.; Marx, W.; Lane, M.M.; Leggio, G.M.; Grosso, G. Ultra-processed food consumption and depressive symptoms in a Mediterranean cohort. Nutrients 2023, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandifar, A.; Badrfam, R.; Mohammaditabar, M.; Kargar, B.; Goodarzi, S.; Hajialigol, A.; Ketabforoush, S.; Heidari, A.; Fathi, H.; Shafiee, A.; et al. The effect of prebiotics and probiotics on levels of depression, anxiety, and cognitive function: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Brain Behav. 2025, 15, e70401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Harty, S.; Johnson, K.V.; Moeller, A.H.; Carmody, R.N.; Lehto, S.M.; Erdman, S.E.; Dunbar, R.I.M.; Burnet, P.W.J. The role of the microbiome in the neurobiology of social behaviour. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2020, 95, 1131–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evrensel, A.; Ceylan, M.E. The Gut-Brain Axis: The Missing Link in Depression. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2015, 13, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Du, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Tao, F. Potential Therapeutic Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Chronic Pain. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2024, 22, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; He, M.; Hassan, A.; Ullah, M.; Zhang, L.; Rashid Khan, M.; Din, A.U.; Ullah, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, G. Mood and microbes: A comprehensive review of intestinal microbiota’s impact on depression. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1295766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitz, J. Role of Kynurenine Metabolism Pathway Activation in Major Depressive Disorders. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 31, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, S.M.; van den Oever, E.J.; Haarman, B.C.M.; Grandjean, E.L.; Nuninga, J.O.; van de Rest, O.; Sommer, I.E. An Anti-Inflammatory Diet and Its Potential Benefit for Individuals with Mental Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matison, A.P.; Milte, C.M.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J.; Daly, R.M.; Torres, S.J. Association between dietary protein intake and changes in health-related quality of life in older adults: Findings from the AusDiab 12-year prospective study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Di Ciaula, A.; Mahdi, L.; Jaber, N.; Di Palo, D.M.; Graziani, A.; Baffy, G.; Portincasa, P. Unraveling the role of the human gut microbiome in health and diseases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Ding, W.; Ling, Z.; Liu, J.; Cai, G. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in depression: Unraveling the relationships and therapeutic opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1644160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, B. Bioactive Compounds as Inhibitors of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Dysfunctions via Regulation of Cellular Redox Balance and Histone Acetylation State. Foods 2023, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Gangwisch, J.E.; Borisini, A.; Wootton, R.E.; Mayer, E.A. Food and mood: How do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? BMJ 2020, 369, m2382, Erratum in BMJ 2020, 371, m4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzone, S.; Charitos, I.A.; Mandorino, M.; Maggiore, M.E.; Capozzi, L.; Cakani, B.; Dias Lopes, G.C.; Bocchio-Chiavetto, L.; Colella, M. Can We Modulate Our Second Brain and Its Metabolites to Change Our Mood? A Systematic Review on Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Future Directions of “Psychobiotics”. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Barquera, S.; Corvalan, C.; Hofman, K.J.; Monteiro, C.; Ng, S.W.; Swart, E.C.; Taillie, L.S. Towards unified and impactful policies to reduce ultra-processed food consumption and promote healthier eating. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bot, M.; Brouwer, I.A.; Roca, M.; Kohls, E.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Watkins, E.; van Grootheest, G.; Cabout, M.; Hegerl, U.; Gili, M.; et al. Effect of Multinutrient Supplementation and Food-Related Behavioral Activation Therapy on Prevention of Major Depressive Disorder Among Overweight or Obese Adults with Subsyndromal Depressive Symptoms: The MooDFOOD Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinella, D.; Raoul, P.C.; Valeriani, E.; Venturini, I.; Cintoni, M.; Severino, A.; Galli, F.S.; Mora, V.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; et al. The Detrimental Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Human Gut Microbiome and Gut Barrier. Nutrients 2025, 17, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Travica, N.; Dissanayaka, T.; Ashtree, D.N.; Gauci, S.; Lotfaliany, M.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Marx, W. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Domain | Representative Evidence (2020–2025) | Main Findings | Mechanistic Pathways | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean-style diet (MD) | [1,10,23] | ↓ depressive symptoms in MDD and subthreshold depression; moderate-quality evidence | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, ↑ SCFA, ↓ kynurenine shift | Feasible adjunct to standard psychiatric care; adherence essential |

| Ultra-processed food (UPF) | [12] | ↑ risk of depression and anxiety (25–40% higher risk in top quartile intake) | Dysbiosis, ↑ inflammation, glycemic instability, dopaminergic dysregulation | Reduce UPF consumption; integrate food policy and public-health education |

| Psychobiotics/Prebiotics | [42] | Small-to-moderate improvement in depressive symptoms (multi-strain, ≥8 weeks) | ↑ SCFA, ↓ IL-6/TNF-α, normalized HPA axis, ↓ IDO activation | Safe adjunctive therapy; requires strain-specific standardization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marano, G.; Traversi, G.; Mazza, O.; Caroppo, E.; Capristo, E.; Gaetani, E.; Mazza, M. The Immune Mind: Linking Dietary Patterns, Microbiota, and Psychological Health. Nutrients 2026, 18, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010096

Marano G, Traversi G, Mazza O, Caroppo E, Capristo E, Gaetani E, Mazza M. The Immune Mind: Linking Dietary Patterns, Microbiota, and Psychological Health. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarano, Giuseppe, Gianandrea Traversi, Osvaldo Mazza, Emanuele Caroppo, Esmeralda Capristo, Eleonora Gaetani, and Marianna Mazza. 2026. "The Immune Mind: Linking Dietary Patterns, Microbiota, and Psychological Health" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010096

APA StyleMarano, G., Traversi, G., Mazza, O., Caroppo, E., Capristo, E., Gaetani, E., & Mazza, M. (2026). The Immune Mind: Linking Dietary Patterns, Microbiota, and Psychological Health. Nutrients, 18(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010096