Modulating the Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes: Nutritional and Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gut Dysbiosis and Diabetes Pathogenesis

2.1. Increased Gut Permeability

2.2. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

2.3. Gut-Derived Metabolites

2.4. Toll-like Receptor Activation

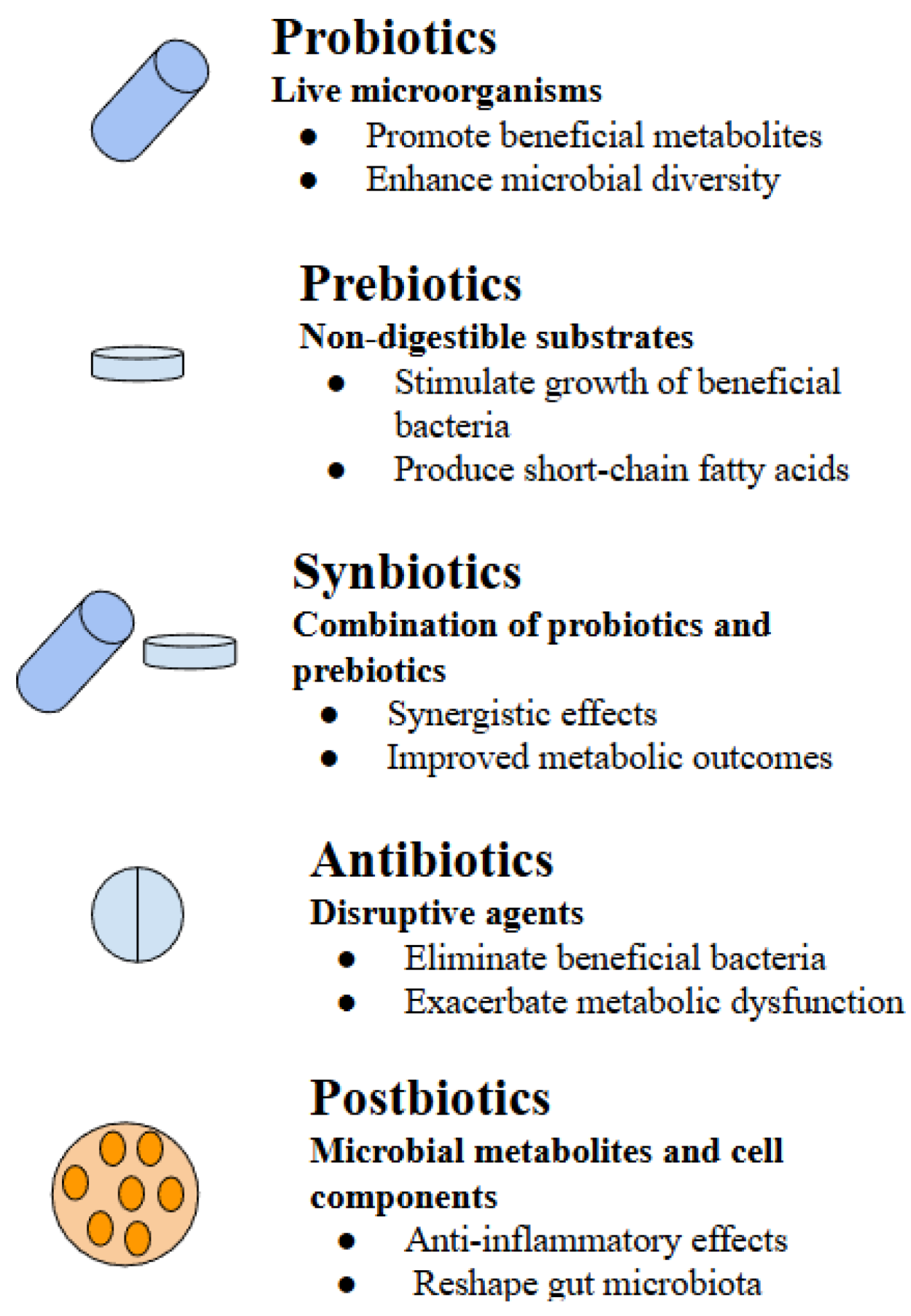

3. Probiotics

4. Prebiotics

5. Synbiotics

6. Antibiotics

7. Postbiotics

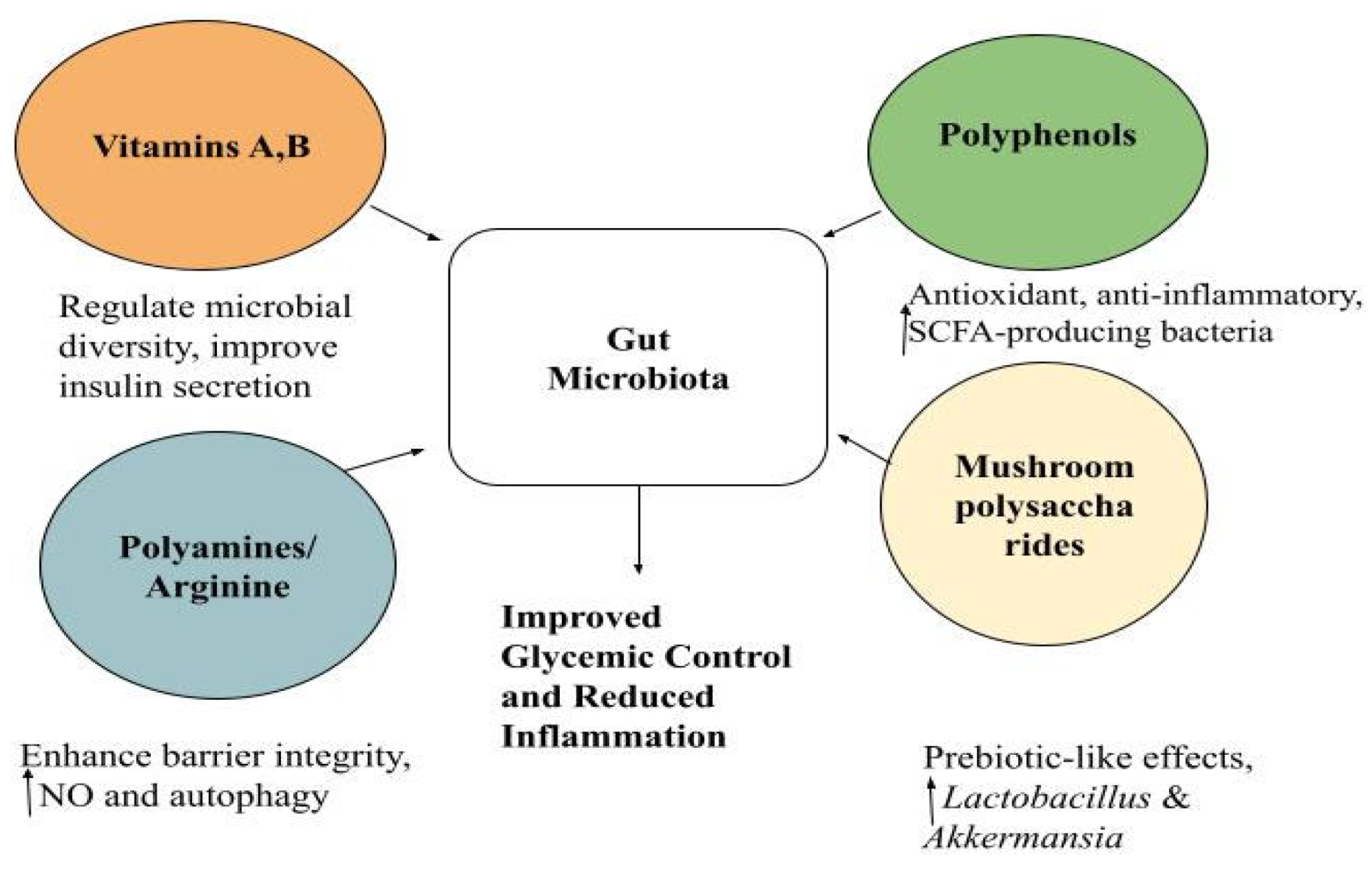

8. The Combined Role of Vitamins, Polyamines, Polyphenols and Mushroom Polysaccharides

8.1. Vitamins

8.2. Polyamines and Arginine Supplementation

8.3. Polyphenols

8.4. Mushroom-Derived Polysaccharides

9. Discussion

10. Future Directions and Personalized Nutrition

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, E.; Lim, S.; Lamptey, R.; Webb, D.R.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 Diabetes. Lancet 2022, 400, 1803–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarska, E.; Wasiak, J.; Gajewska, A.; Steć, G.; Jasińska, J.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Exploring the Significance of Gut Microbiota in Diabetes Pathogenesis and Management-A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyriki, D.; Nikolaidis, C.; Stavropoulou, E.; Bezirtzoglou, I.; Tsigalou, C.; Vradelis, S.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Exploring the Gut Microbiome’s Role in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Insights and Interventions. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Peters, B.A.; Yu, B.; Grove, M.L.; Wang, T.; Xue, X.; Thyagarajan, B.; Daviglus, M.; Boerwinkle, E.; Hu, G.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Blood Metabolites Related to Fiber Intake and Type 2 Diabetes. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Tripathi, P. Gut Microbiome and Type 2 Diabetes: Where We Are and Where to Go? J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 63, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Durán, E.; García-Galindo, J.J.; López-Murillo, L.D.; Huerta-Huerta, A.; Balleza-Alejandri, L.R.; Beltrán-Ramírez, A.; Anaya-Ambriz, E.J.; Suárez-Rico, D.O. Microbiota and Inflammatory Markers: A Review of Their Interplay, Clinical Implications, and Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.P.; Wang, B.; Jain, S.; Ding, J.; Rejeski, J.; Furdui, C.M.; Kitzman, D.W.; Taraphder, S.; Brechot, C.; Kumar, A.; et al. A Mechanism by Which Gut Microbiota Elevates Permeability and Inflammation in Obese/Diabetic Mice and Human Gut. Gut 2023, 72, 1848–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolinska, S.; Popescu, F.-D.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. A Review of the Influence of Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics on the Human Gut Microbiome and Intestinal Integrity. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The Effect of Probiotics on the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by Human Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Rodrigues E-Lacerda, R.; Barra, N.G.; Kukje Zada, D.; Robin, N.; Mehra, A.; Schertzer, J.D. Postbiotic Impact on Host Metabolism and Immunity Provides Therapeutic Potential in Metabolic Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2025, 46, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo-Rodrigues, H.; Sousa, A.S.; Relvas, J.B.; Tavaria, F.K.; Pintado, M. An Overview on Mushroom Polysaccharides: Health-Promoting Properties, Prebiotic and Gut Microbiota Modulation Effects and Structure-Function Correlation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 333, 121978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Maradny, Y.A.; Abouakkada, A.S.; Abbass, A.A.G.; Abaza, A.F.; El-Fakharany, E.M. Prebiotic Properties and Antioxidant Effect of Crude Extracts and Polysaccharides from Agaricus Bisporus and Pleurotus Ostreatus Mushrooms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurilshikov, A.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Bacigalupe, R.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Wang, J.; Demirkan, A.; Le Roy, C.I.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; Finnicum, C.T.; Liu, X.; et al. Large-Scale Association Analyses Identify Host Factors Influencing Human Gut Microbiome Composition. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Bahl, M.I.; Baunwall, S.M.D.; Hvas, C.L.; Licht, T.R. Determining Gut Microbial Dysbiosis: A Review of Applied Indexes for Assessment of Intestinal Microbiota Imbalances. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00395-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyriki, D.; Nikolaidis, C.G.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Voidarou, C.; Stavropoulou, E.; Tsigalou, C. The Gut Microbiota and Aging: Interactions, Implications, and Interventions. Front. Aging 2025, 6, 1452917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootte, R.S.; Vrieze, A.; Holleman, F.; Dallinga-Thie, G.M.; Zoetendal, E.G.; de Vos, W.M.; Groen, A.K.; Hoekstra, J.B.L.; Stroes, E.S.; Nieuwdorp, M. The Therapeutic Potential of Manipulating Gut Microbiota in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, K.; Fan, H.; Wei, M.; Xiong, Q. Targeting the Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1114424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielka, W.; Przezak, A.; Pawlik, A. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Angarita, L.; Morillo, V.; Navarro, C.; Martínez, M.S.; Chacín, M.; Torres, W.; Rajotia, A.; Rojas, M.; Cano, C.; et al. Microbiota and Diabetes Mellitus: Role of Lipid Mediators. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, D.; Fang, Z.; Jie, Z.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Ji, L. Human Gut Microbiota Changes Reveal the Progression of Glucose Intolerance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, C.G.; Gyriki, D.; Stavropoulou, E.; Karlafti, E.; Didangelos, T.; Tsigalou, C.; Thanopoulou, A. Targeting the TLR4 Axis with Microbiota-Oriented Interventions and Innovations in Diabetes Therapy: A Narrative Review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1701504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, T.P.M.; Rampanelli, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Vallance, B.A.; Verchere, C.B.; van Raalte, D.H.; Herrema, H. Gut Microbiota as a Trigger for Metabolic Inflammation in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 571731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, E.; Kadac-Czapska, K.; Grembecka, M. The Importance of Food Quality, Gut Motility, and Microbiome in SIBO Development and Treatment. Nutrition 2024, 124, 112464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, M.; Górna, I.; Woźniak, D.; Przysławski, J.; Drzymała-Czyż, S. Association between Gut Dysbiosis and the Occurrence of SIBO, LIBO, SIFO and IMO. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroka, N.; Rydzewska-Rosołowska, A.; Kakareko, K.; Rosołowski, M.; Głowińska, I.; Hryszko, T. Show Me What You Have Inside—The Complex Interplay between SIBO and Multiple Medical Conditions—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heianza, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, X.; DiDonato, J.A.; Bray, G.A.; Sacks, F.M.; Qi, L. Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Amino Acid Metabolites and Improvements in Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose Metabolism: The POUNDS Lost Trial. Gut 2019, 68, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. Endogenous Toll-like Receptor Ligands and Their Biological Significance. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 2592–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.C.; Bueno, A.A.; de Souza, R.G.M.; Mota, J.F. Gut Microbiota, Probiotics and Diabetes. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caesar, R.; Tremaroli, V.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Cani, P.D.; Bäckhed, F. Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota and Dietary Lipids Aggravates WAT Inflammation through TLR Signaling. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velloso, L.A.; Folli, F.; Saad, M.J. TLR4 at the Crossroads of Nutrients, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Mechanisms of Inflammatory Responses and Development of Insulin Resistance: How Are They Interlinked? J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.P.; Volchkov, P.; Kobayashi, K.S.; Chervonsky, A.V. Microbiota Regulates Type 1 Diabetes through Toll-like Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9973–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G. Probiotics: Definition, Scope and Mechanisms of Action. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasbarrini, G.; Bonvicini, F.; Gramenzi, A. Probiotics History. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrc, R.F. Probiotics in Man and Animals. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1989, 66, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, S.; Hill, C.; Johansen, E.; Obis, D.; Pot, B.; Sanders, M.E.; Tremblay, A.; Ouwehand, A.C. Criteria to Qualify Microorganisms as “Probiotic” in Foods and Dietary Supplements. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Zmora, N.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. The Pros, Cons, and Many Unknowns of Probiotics. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roobab, U.; Batool, Z.; Manzoor, M.F.; Shabbir, M.A.; Khan, M.R.; Aadil, R.M. Sources, Formulations, Advanced Delivery and Health Benefits of Probiotics. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgaço, M.K.; Oliveira, L.G.S.; Costa, G.N.; Bianchi, F.; Sivieri, K. Relationship between Gut Microbiota, Probiotics, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 9229–9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H.; Jain, S.; Sinha, P.R. Antidiabetic Effect of Probiotic Dahi Containing Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Lactobacillus Casei in High Fructose Fed Rats. Nutrition 2007, 23, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.-W.; Gu, Y.-L.; Mao, X.-Q.; Zhang, L.; Pei, Y.-F. Effects of Probiotics on Type II Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, V.; Hendijani, F. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejtahed, H.S.; Mohtadi-Nia, J.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Niafar, M.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Mofid, V. Probiotic Yogurt Improves Antioxidant Status in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Nutrition 2012, 28, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, O.; Wang, X.; Ojo, O.O.; Brooke, J.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Thompson, T. The Effect of Prebiotics and Oral Anti-Diabetic Agents on Gut Microbiome in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittiphairoj, T.; Pongpirul, K.; Janchot, K.; Mueller, N.T.; Li, T. Probiotics Contribute to Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 12, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, S.; Snydman, D.R. Risk and Safety of Probiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, S129–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudegan, F.; Daniali, M.; Hassani, S.; Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. Reappraisal of Probiotics’ Safety in Human. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 129, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prebiotics: Preferential Substrates for Specific Germs?—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11157349/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Gibson, G.R.; Probert, H.M.; Loo, J.V.; Rastall, R.A.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary Modulation of the Human Colonic Microbiota: Updating the Concept of Prebiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2004, 17, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics and the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindels, L.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; Cani, P.D.; Walter, J. Towards a More Comprehensive Concept for Prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, M.P.L.; Altomare, A.; Emerenziani, S.; Di Rosa, C.; Ribolsi, M.; Balestrieri, P.; Iovino, P.; Rocchi, G.; Cicala, M. Mechanisms of Action of Prebiotics and Their Effects on Gastro-Intestinal Disorders in Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, L.d.F.; de Vos, P.; Fabi, J.P. From Structure to Function: How Prebiotic Diversity Shapes Gut Integrity and Immune Balance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Intestinal Health and Disease: From Biology to the Clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barengolts, E. Gut Microbiota, Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Synbiotics in Management of Obesity and Prediabetes: Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, C.; Gallagher, E.; Horton, F.; Ellis, R.J.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Wu, H.; Jaiyeola, E.; Diribe, O.; Duparc, T.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Host–Microbiome Interactions in Human Type 2 Diabetes Following Prebiotic Fibre (Galacto-Oligosaccharide) Intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 1869–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolucci, A.C.; Hume, M.P.; Martínez, I.; Mayengbam, S.; Walter, J.; Reimer, R.A. Prebiotics Reduce Body Fat and Alter Intestinal Microbiota in Children Who Are Overweight or with Obesity. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, M.L.E.; Lucarini, L.; Biffi, B.; Rafanelli, E.; Pietramellara, G.; Durante, M.; Vidali, S.; Provensi, G.; Madiai, S.; Gheri, C.F.; et al. Effect of Mediterranean Diet Enriched in High Quality Extra Virgin Olive Oil on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in Obese and Normal Weight Adult Subjects. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez Quintero, D.F.; Kok, C.R.; Hutkins, R. The Future of Synbiotics: Rational Formulation and Design. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 919725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Zulewska, J.; Xiong, K.; Yang, Z. Synergy between Oligosaccharides and Probiotics: From Metabolic Properties to Beneficial Effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 4078–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, I.M.C.; Mollerup, S.; Broholm, C.; Baker, A.; Holm, M.K.A.; Pedersen, M.S.; Pinholt, M.; Westh, H.; Petersen, A.M. Synbiotic Intervention with Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and Inulin in Healthy Volunteers Increases the Abundance of Bifidobacteria but Does Not Alter Microbial Diversity. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0108722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.; Honwichit, O.; Funnuam, T.; Charoensiddhi, S.; Nitisinprasert, S.; Nielsen, D.S.; Nakphaichit, M. Synergistic Activity of Limosilactobacillus Reuteri KUB-AC5 and Water-Based Plants against Salmonella Challenge in a Human in Vitro Gut Model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Bai, P.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, L. Clostridium Tyrobutyricum in Combination with Chito-Oligosaccharides Modulate Inflammation and Gut Microbiota for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 18497–18506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, P.M.; Telo, G.H.; Ramalho, R.; Sbaraini, M.; Leivas, G.; Martins, A.F.; Schaan, B.D. The Effect of Probiotics, Prebiotics or Synbiotics on Metabolic Outcomes in Individuals with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, W.; Kong, W.; Zhang, J.; Liao, Y.; Min, J.; Zeng, T. Glucose Parameters, Inflammation Markers, and Gut Microbiota Changes of Gut Microbiome–Targeted Therapies in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, 2980–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, K.; Saadati, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Asbaghi, O.; Ghaemi, F.; Pashayee-Khamene, F.; Yari, Z.; de Courten, B. Probiotics and Synbiotics Supplementation Improve Glycemic Control Parameters in Subjects with Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of Randomized Clinical Trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 184, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Wang, L.; Tian, P.; Jin, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Zhu, M. The Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Glucolipid Metabolism in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, D.; Haque, M.M.; Gote, M.; Jain, M.; Bhaduri, A.; Dubey, A.K.; Mande, S.S. A Prospective Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Response Relationship Study to Investigate Efficacy of Fructo-Oligosaccharides (FOS) on Human Gut Microflora. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francino, M.P. Antibiotics and the Human Gut Microbiome: Dysbioses and Accumulation of Resistances. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenneman, A.C.; Weidner, M.; Chen, L.A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Blaser, M.J. Antibiotics in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes and Inflammatory Diseases of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, K.H.; Knop, F.K.; Frost, M.; Hallas, J.; Pottegård, A. Use of Antibiotics and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 3633–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobel, Y.R.; Cox, L.M.; Kirigin, F.F.; Bokulich, N.A.; Yamanishi, S.; Teitler, I.; Chung, J.; Sohn, J.; Barber, C.M.; Goldfarb, D.S.; et al. Metabolic and Metagenomic Outcomes from Early-Life Pulsed Antibiotic Treatment. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Covington, A.; Pamer, E.G. The Intestinal Microbiota: Antibiotics, Colonization Resistance, and Enteric Pathogens. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 279, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vich Vila, A.; Collij, V.; Sanna, S.; Sinha, T.; Imhann, F.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Mujagic, Z.; Jonkers, D.M.A.E.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Fu, J.; et al. Impact of Commonly Used Drugs on the Composition and Metabolic Function of the Gut Microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayor, M.; Shah, S.H.; Murthy, V.; Shah, R.V. Molecular Aspects of Lifestyle and Environmental Effects in Patients with Diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, C.; Giordano, L.; Mihaila, S.M.; Masereeuw, R.; Ortiz, A.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D. Postbiotics and Kidney Disease. Toxins 2022, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, E.; De Paepe, K.; Van de Wiele, T. Postbiotics and Their Health Modulatory Biomolecules. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żółkiewicz, J.; Marzec, A.; Ruszczyński, M.; Feleszko, W. Postbiotics—A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Olmo, M.; Araña, M.; Urtasun, R.; Encio, I.J.; Barajas, M. Role of Postbiotics in Diabetes Mellitus: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Foods 2021, 10, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Thangaraj, P.; Kim, J.-H. Postbiotics: Functional Food Materials and Therapeutic Agents for Cancer, Diabetes, and Inflammatory Diseases. Foods 2023, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourebaba, Y.; Marycz, K.; Mularczyk, M.; Bourebaba, L. Postbiotics as Potential New Therapeutic Agents for Metabolic Disorders Management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.; Garg, A.; Ashique, S.; Bhatt, S. Potential of Postbiotics for the Treatment of Metabolic Disorders. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Joung, M.; Park, J.-H.; Ha, S.K.; Park, H.-Y. Role of Postbiotics in Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelazez, A.; Alshehry, G.; Algarni, E.; Al Jumayi, H.; Abdel-Motaal, H.; Meng, X.-C. Postbiotic Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid and Camel Milk Intervention as Innovative Trends Against Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia in Streptozotocin-Induced C57BL/6J Diabetic Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 943930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kwak, W.; Nam, Y.; Baek, J.; Lee, Y.; Yoon, S.; Kim, W. Effect of Postbiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LRCC5314 Supplemented in Powdered Milk on Type 2 Diabetes in Mice. J. Dairy. Sci. 2024, 107, 5301–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Jin, R.; Li, S.; Wei, J.; Wei, H.; Chen, T. Improvement Effect of a Next-Generation Probiotic L. plantarum-pMG36e-GLP-1 on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via the Gut-Pancreas-Liver Axis. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3179–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, X.-J.; Xie, W.; Su, Z.-A.; Qin, G.-M.; Yu, C.-H. Postbiotics: Emerging Therapeutic Approach in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1359949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, T.; Luo, R.; Liu, J.; Jin, R.; Peng, X. Recent Advances and Potentiality of Postbiotics in the Food Industry: Composition, Inactivation Methods, Current Applications in Metabolic Syndrome, and Future Trends. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 5768–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, N.G.; Anhê, F.F.; Cavallari, J.F.; Singh, A.M.; Chan, D.Y.; Schertzer, J.D. Micronutrients Impact the Gut Microbiota and Blood Glucose. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 250, R1–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Alkhalidy, H.; Liu, D. The Emerging Role of Polyphenols in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Molecules 2021, 26, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Sarocka, A.; Penzes, N.; Biro, R.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Sevcikova, A.; Ciernikova, S.; Omelka, R. Protective Role of Dietary Polyphenols in the Management and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2025, 17, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Németh, Z.; Paulinné Bukovics, M.; Sümegi, L.D.; Sturm, G.; Takács, I.; Simon-Szabó, L. The Importance of Edible Medicinal Mushrooms and Their Potential Use as Therapeutic Agents Against Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.; Fang, M.; Li, Y.; Cai, L.; Han, R.; Sun, W.; Jiang, X.; Chen, L.; Du, J.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Interactions between Gut Microbiota and Natural Bioactive Polysaccharides in Metabolic Diseases: Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R.; Fresán, U.; Marsh, K.; Miles, F.L.; Saunders, A.V.; Haddad, E.H.; Heskey, C.E.; Johnston, P.; Larson-Meyer, E.; et al. The Safe and Effective Use of Plant-Based Diets with Guidelines for Health Professionals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, W.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Vitamin B12 and Gut-Brain Homeostasis in the Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke. eBioMedicine 2021, 73, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Pham, V.T.; Steinert, R.E.; Zhernakova, A.; Fu, J. Microbial Vitamin Production Mediates Dietary Effects on Diabetic Risk. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2154550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaner, W.S. Vitamin A Signaling and Homeostasis in Obesity, Diabetes, and Metabolic Disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 197, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G. Roles of Vitamin A Status and Retinoids in Glucose and Fatty Acid Metabolism. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonakdar, M.; Czuba, L.C.; Han, G.; Zhong, G.; Luong, H.; Isoherranen, N.; Vaishnava, S. Gut Commensals Expand Vitamin A Metabolic Capacity of the Mammalian Host. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1084–1092.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; He, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, P.; Li, K.; Fang, A. Dietary Total Vitamin A, β-Carotene, and Retinol Intake and the Risk of Diabetes in Chinese Adults with Plant-Based Diets. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e4106–e4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Isa, Z.; Ismail, R.; Ja’afar, M.H.; Ismail, N.H.; Mohd Tamil, A.; Mat Nasir, N.; Baharudin, N.; Ab Razak, N.H.; Zainol Abidin, N.; Miller, V.; et al. Vitamin Intake and Its Association with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) among Malaysian Adults. BMC Public. Health 2025, 25, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, F.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Qiao, G. Association between Dietary Vitamin A Intake and Risk of Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qin, L.; Zheng, J.; Tong, L.; Lu, W.; Lu, C.; Sun, J.; Fan, B.; Wang, F. Research Progress on the Relationship between Vitamins and Diabetes: Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schibalski, R.S.; Shulha, A.S.; Tsao, B.P.; Palygin, O.; Ilatovskaya, D.V. The Role of Polyamine Metabolism in Cellular Function and Physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C341–C356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Molina, B.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Lambertos, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Peñafiel, R. Dietary and Gut Microbiota Polyamines in Obesity- and Age-Related Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeo, F.; Eisenberg, T.; Pietrocola, F.; Kroemer, G. Spermidine in Health and Disease. Science 2018, 359, eaan2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Pan, J.; Guo, M.; Duan, H.; Zhang, H.; Narbad, A.; Zhai, Q.; Tian, F.; Chen, W. Gut Microbiota and Anti-Aging: Focusing on Spermidine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 10419–10437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Ni, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tu, W.; Ni, L.; Zhuge, F.; Zheng, A.; Hu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, L.; et al. Spermidine Improves Gut Barrier Integrity and Gut Microbiota Function in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1832857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüse, B.; Holland, T.; Rauh, M.; Gerlach, R.G.; Mattner, J. L-Arginine Metabolism as Pivotal Interface of Mutual Host–Microbe Interactions in the Gut. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2222961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolzan, J.W.; Stein, J.A.; Rood, J.C.; Beyl, R.A.; Yang, S.; Greenway, F.L.; Lieberman, H.R. Effects of Acute Arginine Supplementation on Neuroendocrine, Metabolic, Cardiovascular, and Mood Outcomes in Younger Men: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrition 2022, 101, 111658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatti, P.; Monti, L.D.; Valsecchi, G.; Magni, F.; Setola, E.; Marchesi, F.; Galli-Kienle, M.; Pozza, G.; Alberti, K.G.M.M. Long-Term Oral l-Arginine Administration Improves Peripheral and Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatanawi, A.; Momani, M.S.; Al-Aqtash, R.; Hamdan, M.H.; Gharaibeh, M.N. L-Citrulline Supplementation Increases Plasma Nitric Oxide Levels and Reduces Arginase Activity in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 584669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T.; Wainstein, J.; Gilad, S.; Limor, R.; Boaz, M.; Stern, N. Serum Asymmetric Dimethylarginine and Arginine Levels Predict Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33, e2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Samtiya, M.; Dhewa, T.; Mishra, V.; Aluko, R.E. Health Benefits of Polyphenols: A Concise Review. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.L.Y.; Co, V.A.; El-Nezami, H. Dietary Polyphenol Impact on Gut Health and Microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarewicz, M.; Drożdż, I.; Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A. The Interactions between Polyphenols and Microorganisms, Especially Gut Microbiota. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Tabashsum, Z.; Anderson, M.; Truong, A.; Houser, A.K.; Padilla, J.; Akmel, A.; Bhatti, J.; Rahaman, S.O.; Biswas, D. Effectiveness of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Prebiotic-like Components in Common Functional Foods. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2020, 19, 1908–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, H. Dietary Polyphenol, Gut Microbiota, and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, C.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; Yu, J.; Cao, H.; Wang, M. The Anti-Diabetic Activity of Polyphenols-Rich Vinegar Extract in Mice via Regulating Gut Microbiota and Liver Inflammation. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.; Oliveira, J.; Pinho, A.; Carvalho, E. The Role of Nutraceutical Containing Polyphenols in Diabetes Prevention. Metabolites 2022, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, L.; Graziani, A.; Baffy, G.; Mitten, E.K.; Portincasa, P.; Khalil, M. Unlocking Polyphenol Efficacy: The Role of Gut Microbiota in Modulating Bioavailability and Health Effects. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T. Possible Side Effects of Polyphenols and Their Interactions with Medicines. Molecules 2023, 28, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Luo, D.; Guan, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, X. Mushroom Polysaccharides with Potential in Anti-Diabetes: Biological Mechanisms, Extraction, and Future Perspectives: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1087826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, A.O.; Adetunji, C.O.; Oyewole, O.A.; Popoola, O.A.; Mathew, J.T. Application of Mushroom in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus. In Mushroom Biotechnology for Improved Agriculture and Human Health; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 209–219. ISBN 978-1-394-21269-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Hao, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y. Armillariella Tabescens Polysaccharide Treated Rats with Oral Ulcers through Modulation of Oral Microbiota and Activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yu, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q.; Tian, F. Role of Dietary Edible Mushrooms in the Modulation of Gut Microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xiao, D.; Liu, W.; Song, Y.; Zou, B.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Cai, Y.; Liu, D.; Liao, Q.; et al. Intake of Ganoderma Lucidum Polysaccharides Reverses the Disturbed Gut Microbiota and Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Du, H.; Hu, Q.; Yang, W.; Pei, F.; Xiao, H. Health Benefits of Edible Mushroom Polysaccharides and Associated Gut Microbiota Regulation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6646–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Pan, L.; Wu, Q.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Fang, X.; Dong, S.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Type 2 Diabetes and the Multifaceted Gut-X Axes. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wei, J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, Y.; Hou, G.; Meng, L.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes and Related Diseases. Metabolism 2021, 117, 154712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Tang, C.; Hu, G.; Gao, Z. Targeting Gut Microbiota as a Therapeutic Target in T2DM: A Review of Multi-Target Interactions of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Postbiotics, and Synbiotics with the Intestinal Barrier. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 210, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weninger, S.N.; Manley, A.; Duca, F.A. Managing Glucose Homeostasis Through the Gut Microbiome. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2025, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byndloss, M.; Devkota, S.; Duca, F.; Hendrik Niess, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Orho-Melander, M.; Sanz, Y.; Tremaroli, V.; Zhao, L. The Gut Microbiota and Diabetes: Research, Translation, and Clinical Applications—2023 Diabetes, Diabetes Care, and Diabetologia Expert Forum. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, W.; Brown, J.M. The Gut Microbial Endocrine Organ in Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinology 2020, 162, bqaa235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Zheng, H.; Liao, X. Microbiota: A Potential Orchestrator of Antidiabetic Therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 973624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindrescu, N.M.; Guja, C.; Jinga, V.; Ispas, S.; Curici, A.; Nelson Twakor, A.; Pantea Stoian, A.M. Interactions between Gut Microbiota and Oral Antihyperglycemic Drugs: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasolli, E.; Asnicar, F.; Manara, S.; Zolfo, M.; Karcher, N.; Armanini, F.; Beghini, F.; Manghi, P.; Tett, A.; Ghensi, P.; et al. Extensive Unexplored Human Microbiome Diversity Revealed by Over 150,000 Genomes from Metagenomes Spanning Age, Geography, and Lifestyle. Cell 2019, 176, 649–662.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Niu, J.; Zuo, T.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.; Tang, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ng, E.K.W.; Wong, S.K.H.; et al. Alterations in the Gut Virome in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1257–1269.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, D.; Sroka-Oleksiak, A.; Gurgul, A.; Arent, Z.; Szopa, M.; Bulanda, M.; Małecki, M.T.; Gosiewski, T. Analysis of the Gut Mycobiome in Adult Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Using Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) with Increased Sensitivity—Pilot Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasudha, R.; Das, T.; Kalyana Chakravarthy, S.; Sai Prashanthi, G.; Bhargava, A.; Tyagi, M.; Rani, P.K.; Pappuru, R.R.; Shivaji, S. Gut Mycobiomes Are Altered in People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Retinopathy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.-N.; Ding, W.-Y.; Ning, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.-B. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Inflammatory Markers and Glucose Homeostasis in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 770861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.R.; Fischer, M.; Allegretti, J.R.; LaPlante, K.; Stewart, D.B.; Limketkai, B.N.; Stollman, N.H. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Clostridioides Difficile Infections. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Kendall, C.W.; Vuksan, V. Inulin, Oligofructose and Intestinal Function. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 1431S–1433S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfick, M.M.; Xie, H.; Zhao, C.; Shao, P.; Farag, M.A. Inulin Fructans in Diet: Role in Gut Homeostasis, Immunity, Health Outcomes and Potential Therapeutics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 208, 948–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, F.; Luo, Y.; Wijeyesekera, A.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Lv, Y.; Jin, J.; Sheng, H.; Wang, G.; et al. Differential Effects of Inulin and Fructooligosaccharides on Gut Microbiota Composition and Glycemic Metabolism in Overweight/Obese and Healthy Individuals: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, S.-P.; Choi, H.-J.; Jeong, H.; Park, Y.-S. A Comprehensive Review of Synbiotics: An Emerging Paradigm in Health Promotion and Disease Management. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Chen, T.; Ma, J.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, W.; et al. Unlocking the Power of Postbiotics: A Revolutionary Approach to Nutrition for Humans and Animals. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 725–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikindas, M.L.; Roopchand, D.E.; Tiwari, S.K.; Sichel, L.S.; Karwe, M.V.; Nitin, N.; Fagundes, V.L.; Popov, I.V.; Tagg, J.R.; Lu, X.; et al. An Integrated Engineering Approach to Creating Health-Modulating Postbiotics. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 70, e70326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçıntaş, Y.M.; Bolino, M.J.; Duman, H.; Sarıtaş, S.; Pekdemir, B.; Kalkan, A.E.; Canbolat, A.A.; Bolat, E.; Eker, F.; Miguel Rocha, J.; et al. Prebiotics: Types, Selectivity and Utilization by Gut Microbes. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 76, 798–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, K.; Mansell, T.J. Unveiling the Prebiotic Potential of Polyphenols in Gut Health and Metabolism. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2025, 95, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, M.; Muñoz-González, I.; Cueva, C.; Jiménez-Girón, A.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolomé, B. A Survey of Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Dietary Polyphenols. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 850902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavefve, L.; Howard, L.R.; Carbonero, F. Berry Polyphenols Metabolism and Impact on Human Gut Microbiota and Health. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, M.; Minato, K. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties of Polysaccharides in Mushrooms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 86, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassarella, M.; Blaak, E.E.; Penders, J.; Nauta, A.; Smidt, H.; Zoetendal, E.G. Gut Microbiome Stability and Resilience: Elucidating the Response to Perturbations in Order to Modulate Gut Health. Gut 2021, 70, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Lopez, O.; Martinez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. Holistic Integration of Omics Tools for Precision Nutrition in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardon, K.M.; Canfora, E.E.; Goossens, G.H.; Blaak, E.E. Dietary Macronutrients and the Gut Microbiome: A Precision Nutrition Approach to Improve Cardiometabolic Health. Gut 2022, 71, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Kaul, R.; Harfouche, M.; Arabi, M.; Al-Najjar, Y.; Sarkar, A.; Saliba, R.; Chaari, A. The Effect of Microbiome-Modulating Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics on Glucose Homeostasis in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of Clinical Trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 185, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Wang, F.; Bhosle, A.; Dong, D.; Mehta, R.; Ghazi, A.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Rinott, E.; Ma, S.; et al. Strain-Specific Gut Microbial Signatures in Type 2 Diabetes Identified in a Cross-Cohort Analysis of 8,117 Metagenomes. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2265–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, N.R.; Al Bataineh, M.T.; Alili, R.; Al Safar, H.; Alkhayyal, N.; Prifti, E.; Zucker, J.-D.; Belda, E.; Clément, K. Functional Alterations and Predictive Capacity of Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, Y.; Shafie, N.S.; Amer, M. Integrative Analysis of Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Pathways Reveals Key Microbial and Metabolomic Alterations in Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gutierrez, E.; O’Mahony, A.K.; Dos Santos, R.S.; Marroquí, L.; Cotter, P.D. Gut Microbial Metabolic Signatures in Diabetes Mellitus and Potential Preventive and Therapeutic Applications. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2401654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Miao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J. Gut Microbiome Research: Revealing the Pathological Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4051–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarska, N.G.; Håberg, A.K. Understanding Patterns of the Gut Microbiome May Contribute to the Early Detection and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, S.; Qi, L.; Zalloua, P. From Omics to AI—Mapping the Pathogenic Pathways in Type 2 Diabetes. FEBS Lett. 2025, 599, 3244–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri-Rosario, D.; Martínez-López, Y.E.; Esquivel-Hernández, D.A.; Sánchez-Castañeda, J.P.; Padron-Manrique, C.; Vázquez-Jiménez, A.; Giron-Villalobos, D.; Resendis-Antonio, O. Dysbiosis Signatures of Gut Microbiota and the Progression of Type 2 Diabetes: A Machine Learning Approach in a Mexican Cohort. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1170459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanism | Key Features | Role in Diabetes |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Gut Permeability (“Leaky Gut”) | Dysbiosis disrupts gut barrier integrity. LPS is translocated into circulation. Ethanolamine metabolism dysregulation impairs tight junction proteins Zonula Occludens-1 (Z0-1). | Triggers systemic low-grade chronic inflammation and insulin resistance, Promotes β-cell dysfunction and fatty liver disease. Chronic immune activation maintains dysbiosis. |

| Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) | Overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine. Common in diabetes due to autonomic neuropathy (reduced motility), altered pancreatic function, and frequent use of antibiotics. | Exacerbates gut dysmotility in diabetic individuals. Inhibits insulin receptor signaling via cytokine overproduction, exacerbating insulin resistance. |

| Gut-derived Metabolites | Altered production of SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate), TMAO, bile acids, and indoles. SCFAs regulate glucose metabolism, TMAO and bile acids affect insulin sensitivity and GLP-1 secretion. | Reduced SCFA production contributes to insulin resistance. Elevated TMAO impairs glucose metabolism. Indoles and bile acid derivatives modulate incretin release and inflammation. |

| Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) signaling activation | TLRs detect microbial molecules (e.g., LPS) and regulate immune responses. TLR4 activation connects dietary fat, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction. | Chronic TLR4 activation promotes metabolic inflammation, β-cell dysfunction, and insulin resistance. Links high-fat diets to gut barrier impairment and systemic inflammation. |

| Category | Substance/Examples | Key Microbiota and Metabolic Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Pediococcus acidilactici, Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 | Postponed glucose intolerance, reduced hyperglycemia and insulin resistance; ↓ HbA1c and FBG; improved antioxidant status; enhanced intestinal integrity; caution for infections |

| Prebiotics | inulin, fructooligosaccharides (FOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS), dietary polyphenols | ↑ SCFA production (acetate, butyrate, propionate); immunomodulation; improved barrier integrity; reduced IL-6; weight and fat reduction; selective bacterial stimulation |

| Synbiotics | Oligofructose + Bifidobacteria, fruit-and-vegetable-enriched diets | Improved hyperglycemia; enhanced insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis; improved lipid metabolism; modulation of gut composition |

| Antibiotics | Early-life β-lactam, macrolide, cumulative antibiotic exposure | Rapid microbiota disruption; dose-dependent ↑ T2DM risk; altered community structure; exacerbated obesity and insulin resistance in rodent models |

| Postbiotics | SCFAs, phenolic acids, bacteriocins, sonicated Lactobacillus paracasei, O. formigenes lysates, camel milk-derived, engineered L. plantarum-GLP-1 | Immunomodulation; anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects; improved insulin sensitivity; decreased glucose and lipids; β-cell regeneration; gut barrier enhancement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nikolaidis, C.G.; Gyriki, D.; Stavropoulou, E.; Karlafti, E.; Didangelos, T.; Tsigalou, C.; Thanopoulou, A. Modulating the Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes: Nutritional and Therapeutic Strategies. Nutrients 2026, 18, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010089

Nikolaidis CG, Gyriki D, Stavropoulou E, Karlafti E, Didangelos T, Tsigalou C, Thanopoulou A. Modulating the Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes: Nutritional and Therapeutic Strategies. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikolaidis, Christos G., Despoina Gyriki, Elisavet Stavropoulou, Eleni Karlafti, Triantafyllos Didangelos, Christina Tsigalou, and Anastasia Thanopoulou. 2026. "Modulating the Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes: Nutritional and Therapeutic Strategies" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010089

APA StyleNikolaidis, C. G., Gyriki, D., Stavropoulou, E., Karlafti, E., Didangelos, T., Tsigalou, C., & Thanopoulou, A. (2026). Modulating the Gut Microbiome in Type 2 Diabetes: Nutritional and Therapeutic Strategies. Nutrients, 18(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010089