Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

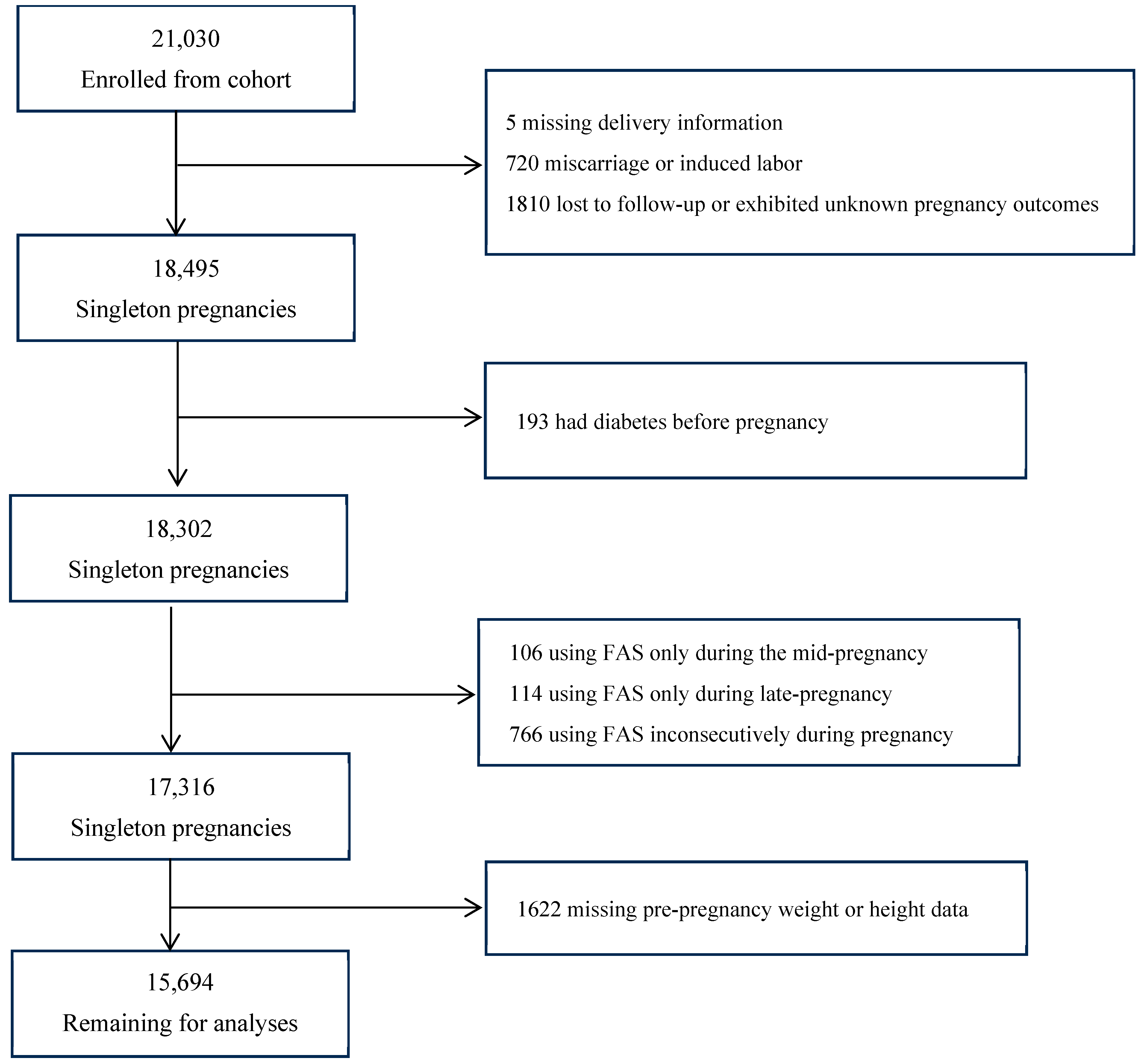

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Exposure and Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Incidence of Pregnancy Outcomes

3.3. Associations Between FAS Duration and Pregnancy Outcomes

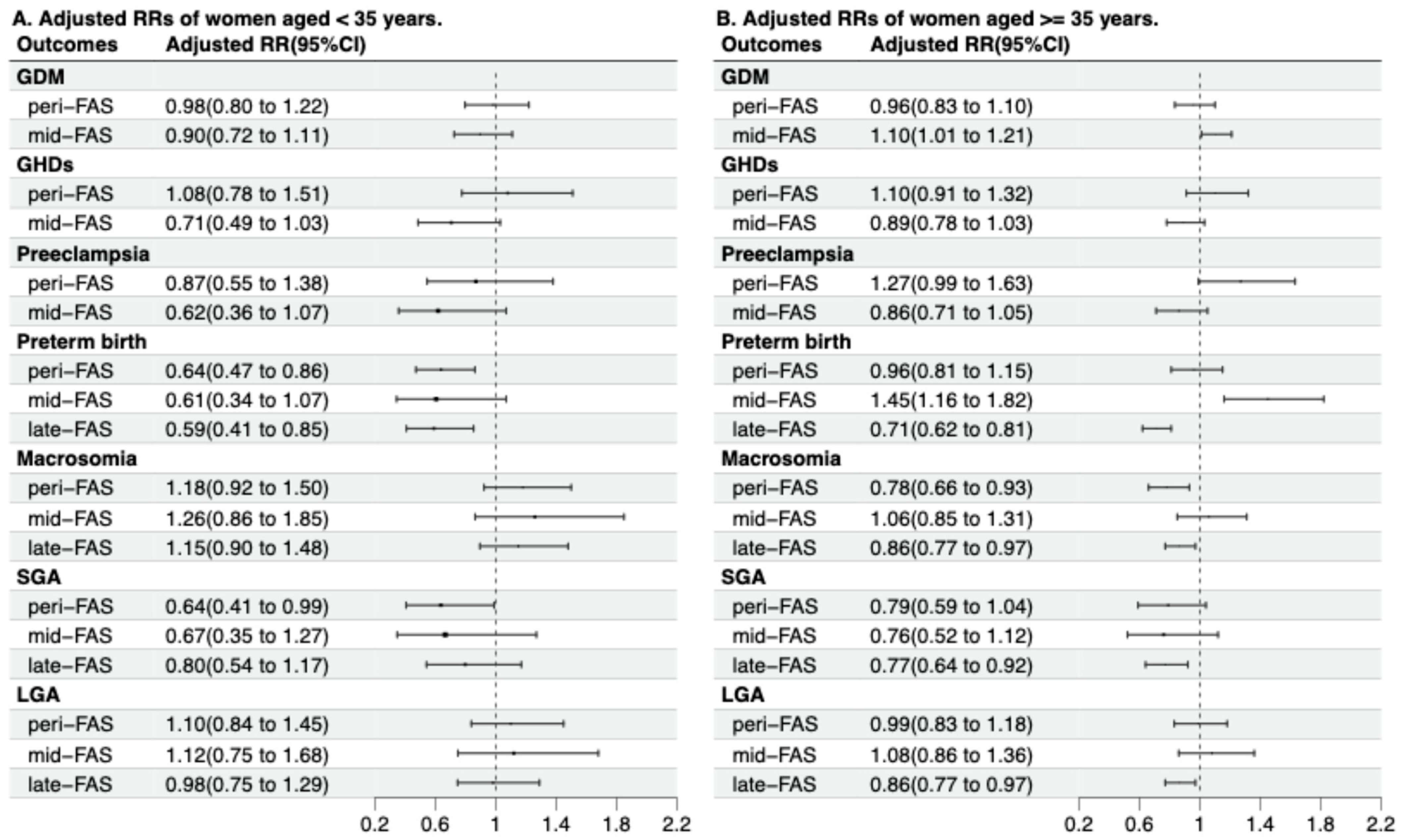

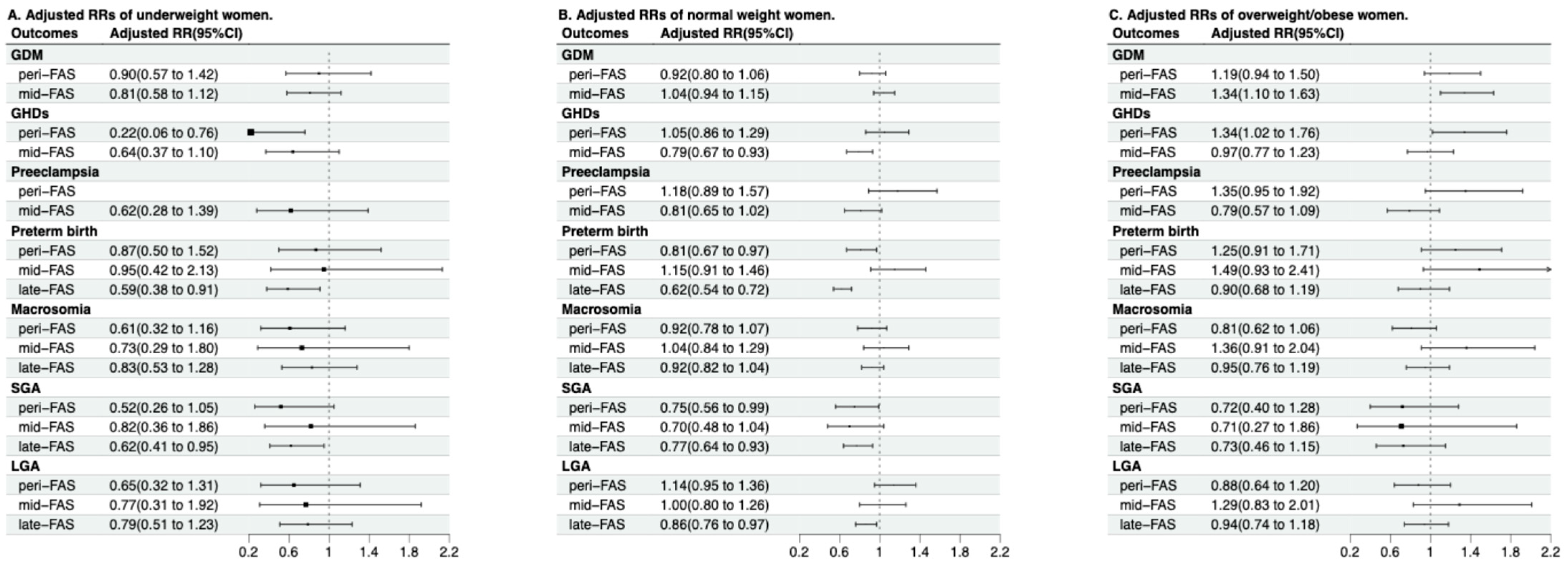

3.4. Modification Effects of Maternal Age and Pre-Pregnancy BMI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristics | Included (n = 15,694) | Excluded (n = 5336) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years, n (%) | ||

| <35 | 3842 (24.5) | 1394 (26.1) |

| 35–39 | 9462 (60.3) | 2945 (55.2) |

| 40–44 | 2253 (14.4) | 923 (17.3) |

| ≥45 | 137 (0.9) | 74 (1.4) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, n (%) | ||

| Underweight | 1347 (8.6) | 265 (7.6) |

| Normal weight | 11,763 (75.0) | 2517 (72.3) |

| Overweight | 2201 (14.0) | 596 (17.1) |

| Obesity | 383 (2.4) | 103 (3.0) |

| Multipara, n (%) | 12,821 (81.69) | 2943 (77.82) |

| Han ethnicity, n (%) | 14,939 (95.19) | 4439 (95.81) |

| Conception mode | ||

| Natural conception | 12,638 (85.3) | 3216 (84.8) |

| IVF or ICSI | 1994 (13.5) | 524 (13.8) |

| Others | 181 (1.2) | 54 (1.4) |

| Maternal education, n (%) | ||

| Primary school or lower | 120 (0.8) | 45 (1.2) |

| Junior high school | 796 (5.1) | 239 (6.4) |

| High school or above | 14,639 (94.1) | 3445 (92.4) |

| Maternal alcohol consumption, n (%) | 888 (5.7) | 293 (5.5) |

| smoking, n (%) | 256 (1.6) | 59 (1.1) |

| south area, n (%) | 10,408 (66.3) | 3588 (67.2) |

| Hematological Indexes | No-FAS | Peri-FAS | Mid-FAS | Late-FAS | p-Value † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 117.6 (110.0 to 125.0) | 117.4 (110.0 to 125.0) | 118.8 (112.0 to 126.0) | 120.6 (114.0 to 127.0) | <0.01 |

| Red blood cell counts (×1012/L) | 3.9 (3.6 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.1) | <0.01 |

| Outcomes | No-FAS | Peri-FAS | Mid-FAS | Late-FAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRs (95% CIs) | RRs (95% CIs) | RRs (95% CIs) | RRs (95% CIs) | |

| GDM † | Reference | 0.93 (0.83, 1.03) | 1.11 (1.03, 1.21) | / |

| GHDs † | Reference | 1.02 (0.87, 1.18) | 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) | / |

| Preeclampsia † | Reference | 1.11 (0.90, 1.37) | 0.81 (0.68, 0.97) | / |

| Preterm birth | Reference | 0.81 (0.70, 0.94) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.39) | 0.69 (0.61, 0.77) |

| Macrosomia | Reference | 0.84 (0.74, 0.96) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.29) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.04) |

| SGA ‡ | Reference | 0.66 (0.53, 0.83) | 0.69 (0.50, 0.96) | 0.72 (0.62, 0.84) |

| LGA ‡ | Reference | 1.11 (0.97, 1.27) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.27) | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) |

| Outcomes | No-FAS | Peri-FAS | Mid-FAS | Late-FAS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | |

| GDM † | 1177 (26.0) | Reference | 702 (24.6) | 0.95 (0.84, 1.07) | 2342 (28.2) | 1.09 (0.99, 1.18) | / | / |

| GHDs † | 470 (10.4) | Reference | 301 (10.6) | 1.14 (0.97, 1.34) | 736 (8.9) | 0.86 (0.75, 0.97) | / | / |

| Preeclampsia † | 223 (4.9) | Reference | 155 (5.4) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) | 336 (4.0) | 0.86 (0.72, 1.03) | / | / |

| Preterm birth | 591 (13.1) | Reference | 310 (10.9) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) | 134 (14.6) | 1.22 (0.99, 1.50) | 694 (9.4) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.76) |

| Macrosomia | 792 (17.5) | Reference | 433 (15.2) | 1.10 (0.96, 1.26) | 171 (18.6) | 1.10 (0.91, 1.33) | 1236 (16.7) | 0.85 (0.76, 0.94) |

| SGA ‡ | 309 (8.1) | Reference | 103 (5.5) | 0.68 (0.53, 0.89) | 44 (5.7) | 0.71 (0.51, 0.99) | 401 (6.0) | 0.74 (0.63, 0.87) |

| LGA ‡ | 758 (19.8) | Reference | 401 (21.6) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.20) | 158 (20.6) | 1.06 (0.87, 1.29) | 1191 (17.7) | 0.89 (0.80, 0.98) |

| p for Interaction | GDM | Preeclampsia | GHDs | Preterm Birth | Macrosomia | SGA | LGA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age and FAS group | 0.14 | 0.50 | 0.35 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.33 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI and FAS group | 0.14 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.90 | 0.20 |

| Maternal age, Pre-pregnancy BMI, and FAS group | 0.26 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.99 | 0.50 |

| Age | FAS Group | GDM † | GHDs † | Preeclampsia † | Preterm Birth | Macrosomia | SGA ‡ | LGA ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <35 | no-FAS | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| peri-FAS | 0.92 (0.75, 1.13) | 1.12 (0.82, 1.55) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.51) | 0.72 (0.55, 0.96) | 1.16 (0.92, 1.47) | 0.57 (0.37, 0.87) | 1.35 (1.05, 1.73) | |

| mid-FAS | 0.76 (0.62, 0.93) | 0.59 (0.41, 0.85) | 0.48 (0.28, 0.80) | 0.51 (0.29, 0.88) | 1.22 (0.84, 1.78) | 0.63 (0.34, 1.19) | 0.97 (0.66, 1.43) | |

| late-FAS | / | / | / | 0.45 (0.32, 0.63) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.38) | 0.75 (0.52, 1.07) | 0.80 (0.62, 1.02) | |

| ≥35 | no-FAS | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| peri-FAS | 1.04 (0.91, 1.18) | 1.12 (0.93, 1.34) | 1.29 (1.01, 1.64) | 0.93 (0.78, 1.11) | 0.79 (0.67, 0.92) | 0.73 (0.56, 0.96) | 1.06 (0.89, 1.25) | |

| mid-FAS | 1.11 (1.02, 1.22) | 0.81 (0.71, 0.92) | 0.81 (0.67, 0.98) | 1.38 (1.10, 1.72) | 1.05, (0.85, 1.30) | 0.72 (0.49, 1.05) | 1.10 (0.88, 1.38) | |

| late-FAS | / | / | / | 0.69 (0.61, 0.78) | 0.87 (0.78, 0.97) | 0.71 (0.60, 0.85) | 0.87 (0.78, 0.97) | |

| p for interaction | <0.01 | 0.12 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.14 |

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | FAS Group | GDM † | GHDs † | Preeclampsia † | Preterm Birth | Macrosomia | SGA ‡ | LGA ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | no-FAS | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| peri-FAS | 0.83 (0.54, 1.26) | 0.17 (0.05, 0.58) | / | 0.80 (0.47, 1.36) | 0.64 (0.34, 1.18) | 0.45 (0.22, 0.88) | 0.68 (0.34, 1.33) | |

| mid-FAS | 0.84 (0.62, 1.15) | 0.65 (0.39, 1.08) | 0.65 (0.31, 1.36) | 0.80 (0.36, 1.77) | 0.74 (0.30, 1.81) | 0.76 (0.34, 1.69) | 0.76 (0.31, 1.87) | |

| late-FAS | / | / | / | 0.63 (0.42, 0.95) | 0.93 (0.61, 1.41) | 0.61 (0.41, 0.91) | 0.85 (0.56, 1.31) | |

| Normal | no-FAS | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| peri-FAS | 0.88 (0.77, 1.01) | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) | 1.06 (0.80, 1.40) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.87) | 0.87 (0.75, 1.01) | 0.72 (0.55, 0.94) | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | |

| mid-FAS | 1.12 (1.01, 1.23) | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08) | 1.11 (0.88, 1.40) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.28) | 0.67 (0.46, 0.99) | 1.01 (0.81, 1.27) | |

| late-FAS | / | / | / | 0.65 (0.57, 0.74) | 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.89) | 0.87 (0.77, 0.98) | |

| Overweight/obesity | no-FAS | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| peri-FAS | 1.04 (0.83, 1.30) | 1.21 (0.93, 1.57) | 1.25 (0.89, 1.76) | 1.10 (0.81, 1.48) | 0.76 (0.58, 0.99) | 0.68 (0.39, 1.19) | 0.96 (0.72, 1.27) | |

| mid-FAS | 1.39 (1.15, 1.67) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) | 0.85 (0.62, 1.16) | 1.46 (0.91, 2.34) | 1.44 (0.97, 2.14) | 0.66 (0.26, 1.70) | 1.41 (0.92, 2.17) | |

| late-FAS | / | / | / | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 1.06 (0.85, 1.31) | 0.67 (0.44, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.81, 1.26) | |

| p for interaction | 0.12 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.20 |

References

- Crider, K.S.; Yang, T.P.; Berry, R.J.; Bailey, L.B. Folate and DNA methylation: A review of molecular mechanisms and the evidence for folate’s role. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Regil, L.M.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Rayco-Solon, P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd007950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Davidson, K.W.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; García, F.A.; Kemper, A.R.; Krist, A.H.; Kurth, A.E.; Landefeld, C.S.; et al. Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2017, 317, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Sha, T.; Gao, X.; He, Q.; Wu, X.; Tian, Q.; Yang, F.; Tang, C.; Wu, X.; Xie, Q.; et al. The Associations between the Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Adverse Birth Outcomes based on a Birth Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Cao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, G. Association between Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy and Risk of Postpartum Depression. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branum, A.M.; Bailey, R.; Singer, B.J. Dietary supplement use and folate status during pregnancy in the United States. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, S.P.; Plumptre, L.; Ly, A.; Berger, H.; Lausman, A.Y.; Croxford, R.; Kim, Y.I.; O’Connor, D.L. Pregnant Canadian Women Achieve Recommended Intakes of One-Carbon Nutrients through Prenatal Supplementation but the Supplement Composition, Including Choline, Requires Reconsideration. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, X.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Maternal high folic acid supplement promotes glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in male mouse offspring fed a high-fat diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 6298–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.E.; Sánchez-Hernández, D.; Reza-López, S.A.; Huot, P.S.; Kim, Y.I.; Anderson, G.H. High folate gestational and post-weaning diets alter hypothalamic feeding pathways by DNA methylation in Wistar rat offspring. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Riley, A.W.; Volk, H.; Caruso, D.; Hironaka, L.; Sices, L.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Ji, Y.; Brucato, M.; et al. Maternal Multivitamin Intake, Plasma Folate and Vitamin B(12) Levels and Autism Spectrum Disorder Risk in Offspring. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2018, 32, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.; Cooper, D.W. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2001, 357, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.S.; Woodside, J.V. Folate and homocysteine. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2000, 3, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, Z.; Ye, R.; Liu, J.; Ren, A. Impact of Periconceptional Folic Acid Supplementation on Low Birth Weight and Small-for-Gestational-Age Infants in China: A Large Prospective Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. 2017, 187, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, C.E.; Brassington, A.H.; Kwong, W.Y.; Sinclair, K.D. One-Carbon Metabolism: Linking Nutritional Biochemistry to Epigenetic Programming of Long-Term Development. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 7, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gueant-Rodriguez, R.M.; Quilliot, D.; Sirveaux, M.A.; Meyre, D.; Gueant, J.L.; Brunaud, L. Folate and vitamin B12 status is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in morbid obesity. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, E.; Correia-Branco, A.; Araújo, J.R.; Meireles, M.; Fernandes, R.; Guardão, L.; Guimarães, J.T.; Martel, F.; Calhau, C. Excess perigestational folic acid exposure induces metabolic dysfunction in post-natal life. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 224, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yajnik, C.S.; Deshpande, S.S.; Jackson, A.A.; Refsum, H.; Rao, S.; Fisher, D.J.; Bhat, D.S.; Naik, S.S.; Coyaji, K.J.; Joglekar, C.V.; et al. Vitamin B12 and folate concentrations during pregnancy and insulin resistance in the offspring: The Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhong, C.; Chen, R.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Cui, W.; Xiong, T.; et al. High-Dose Folic Acid Supplement Use From Prepregnancy Through Midpregnancy Is Associated With Increased Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, e113–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, X.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, H.; Xu, D.; et al. Duration of periconceptional folic acid supplementation and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 28, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.; Pearson, G.; Cutler, J.; Lindheimer, M. Summary of the NHLBI Working Group on Research on Hypertension During Pregnancy. Hypertension 2003, 41, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffoni, S.; De Giuseppe, R.; Stanford, F.C.; Cena, H. Folate status in women of childbearing age with obesity: A review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camier, A.; Kadawathagedara, M.; Lioret, S.; Bois, C.; Cheminat, M.; Dufourg, M.N.; Charles, M.A.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B. Social Inequalities in Prenatal Folic Acid Supplementation: Results from the ELFE Cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Xue, M.; Hellerstein, S.; Cai, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Blustein, J.; Liu, J.M. Association of China’s universal two child policy with changes in births and birth related health factors: National, descriptive comparative study. BMJ 2019, 366, l4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, X.; Yan, Y. Estimated global overweight and obesity burden in pregnant women based on panel data model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.M. University Hospital Advanced Age Pregnant Cohort (UNIHOPE). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03220750 (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, M.; Dou, Y.; Sun, X.; Huang, G.; et al. Association of Maternal Folate and Vitamin B(12) in Early Pregnancy With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steegers, E.A.; von Dadelszen, P.; Duvekot, J.J.; Pijnenborg, R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2010, 376, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capital Institute of Pediatrics; Coordinating Study Group of Nine Cities on the Physical Growth and Development of Children. Growth standard curves of birth weight, length and head circumference of Chinese newborns of different gestation. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2020, 58, 738–746. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, A.; Zhang, L.; Hao, L.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Li, Z. Comparison of blood folate levels among pregnant Chinese women in areas with high and low prevalence of neural tube defects. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, A.; Irwin, R.E.; McNulty, H.; Strain, J.J.; Lees-Murdock, D.J.; McNulty, B.A.; Ward, M.; Walsh, C.P.; Pentieva, K. Gene-specific DNA methylation in newborns in response to folic acid supplementation during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: Epigenetic analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Supplementation of folic acid in pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension: A meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 298, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Shen, M.; Gaudet, L.; Janoudi, G.; Walker, M.; Wen, S.W. Effect of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on gestational hypertension/preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2016, 35, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ocampo, M.P.G.; Araneta, M.R.G.; Macera, C.A.; Alcaraz, J.E.; Moore, T.R.; Chambers, C.D. Folic acid supplement use and the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Women Birth 2018, 31, e77–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.W.; Chen, X.K.; Rodger, M.; White, R.R.; Yang, Q.; Smith, G.N.; Sigal, R.J.; Perkins, S.L.; Walker, M.C. Folic acid supplementation in early second trimester and the risk of preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 45.E1–45.E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catov, J.M.; Nohr, E.A.; Bodnar, L.M.; Knudson, V.K.; Olsen, S.F.; Olsen, J. Association of periconceptional multivitamin use with reduced risk of preeclampsia among normal-weight women in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 169, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.E.; Ferrell, W.R.; Crawford, L.; Wallace, A.M.; Greer, I.A.; Sattar, N. Maternal obesity is associated with dysregulation of metabolic, vascular, and inflammatory pathways. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 4231–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damms-Machado, A.; Weser, G.; Bischoff, S.C. Micronutrient deficiency in obese subjects undergoing low calorie diet. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ge, X.; Huang, K.; Mao, L.; Yan, S.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S.; Hao, J.; Zhu, P.; Niu, Y.; et al. Folic Acid Supplement Intake in Early Pregnancy Increases Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Evidence From a Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, e36–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Peng, Z.; He, Y.; Xu, J.; Ma, X. Effect of folic acid supplementation on preterm delivery and small for gestational age births: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 67, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Peng, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C. Folic Acid and Risk of Preterm Birth: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Qu, P.F.; Dang, S.N.; Li, S.S.; Bai, R.H.; Qin, B.W.; Yan, H. Effect of folic acid supplementation in childbearing aged women during pregnancy on neonate birth weight in Shaanxi province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2016, 37, 1017–1020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulloch, R.E.; Wall, C.R.; Thompson, J.M.D.; Taylor, R.S.; Poston, L.; Roberts, C.T.; Dekker, G.A.; Kenny, L.C.; Simpson, N.A.B.; Myers, J.E.; et al. Folic acid supplementation is associated with size at birth in the Screening for Pregnancy Endpoints (SCOPE) international prospective cohort study. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 147, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.K.Y.; Lu, J.; Leung, T.Y.; Chan, Y.M.; Sahota, D.S. Prospective assessment of INTERGROWTH-21(st) and World Health Organization estimated fetal weight reference curves. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; Culhane, J.F.; Iams, J.D.; Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008, 371, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsmo, H.W.; Jiang, X. One carbon metabolism and early development: A diet-dependent destiny. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, L.; Selhub, J. Interaction between excess folate and low vitamin B12 status. Mol. Aspects Med. 2017, 53, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, B.A.; Shields, B.M.; Brook, A.; Hill, A.; Bhat, D.S.; Hattersley, A.T.; Yajnik, C.S. Lower Circulating B12 Is Associated with Higher Obesity and Insulin Resistance during Pregnancy in a Non-Diabetic White British Population. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troen, A.M.; Mitchell, B.; Sorensen, B.; Wener, M.H.; Johnston, A.; Wood, B.; Selhub, J.; McTiernan, A.; Yasui, Y.; Oral, E.; et al. Unmetabolized folic acid in plasma is associated with reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity among postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, D.P.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, D.M.; Zhang, W.Y. Genomic expression profiles of blood and placenta reveal significant immune-related pathways and categories in Chinese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcken, B.; Bamforth, F.; Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Ritvanen, A.; Renlund, M.; Stoll, C.; Alembik, Y.; Dott, B.; Czeizel, A.E.; et al. Geographical and ethnic variation of the 677C>T allele of 5,10 methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR): Findings from over 7000 newborns from 16 areas world wide. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selhub, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. Excessive folic acid intake and relation to adverse health outcome. Biochimie 2016, 126, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simcox, J.A.; McClain, D.A. Iron and diabetes risk. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | No-FAS (n = 4523) | Peri-FAS (n = 2854) | Mid-FAS (n = 921) | Late-FAS (n = 7396) | p-Value † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years | |||||

| <35 | 1235 (27.3) | 1209 (42.4) | 278 (30.2) | 1120 (15.1) | <0.01 |

| 35–39 | 2541 (56.2) | 1341 (47.0) | 501 (54.4) | 5079 (68.7) | |

| 40–44 | 705 (15.6) | 289 (10.1) | 133 (14.4) | 1126 (15.2) | |

| ≥45 | 42 (0.9) | 15 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | 71 (1.0) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| Underweight | 389 (8.6) | 227 (8.0) | 79 (8.6) | 652 (8.8) | <0.01 |

| Normal weight | 3325 (73.5) | 2039 (71.4) | 705 (76.5) | 5694 (77.0) | |

| Overweight | 650 (14.4) | 498 (17.4) | 116 (12.6) | 937 (12.7) | |

| Obesity | 159 (3.5) | 90 (3.2) | 21 (2.3) | 113 (1.5) | |

| Multipara, n (%) | 3594 (79.5) | 2078 (72.8) | 755 (82.0) | 6394 (86.5) | <0.01 |

| Han ethnicity, n (%) | 4327 (95.7) | 2603 (91.2) | 882 (95.8) | 7127 (96.4) | <0.01 |

| Conception mode | <0.01 | ||||

| Natural conception | 3586 (79.3) | 2268 (79.5) | 745 (80.9) | 6039 (81.7) | |

| IVF or ICSI | 618 (13.7) | 291 (10.2) | 118 (12.8) | 967 (13.1) | |

| Others | 50 (1.1) | 43 (1.5) | 10 (1.1) | 78 (1.1) | |

| Missing | 269 (5.9) | 252 (8.8) | 48 (5.2) | 312 (4.2) | |

| Maternal education, n (%) | <0.01 | ||||

| Primary school or lower | 50 (1.1) | 19 (0.7) | 4 (0.4) | 47 (0.6) | |

| Junior high school | 386 (8.5) | 118 (4.1) | 33 (3.6) | 259 (3.5) | |

| High school or above | 3986 (88.1) | 2709 (94.9) | 881 (95.7) | 7063 (95.5) | |

| Missing | 101 (2.2) | 8 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 27 (0.4) | |

| Maternal alcohol consumption, n (%) | 102 (2.3) | 160 (5.6) | 56 (6.1) | 570 (7.7) | <0.01 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 73 (1.6) | 60 (2.1) | 8 (0.9) | 115 (1.6) | 0.06 |

| South area, n (%) | 3325 (73.5) | 896 (31.4) | 576 (62.5) | 5611 (75.9) | <0.01 |

| Outcomes | No-FAS | Peri-FAS | Mid-FAS | Late-FAS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | N (%) | aRRs (95% CIs) | |

| GDM † | 1177 (26.0) | Reference | 702 (24.6) | 0.97 (0.86, 1.09) | 2342 (28.2) | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) | / | / |

| GHDs † | 470 (10.4) | Reference | 301 (10.6) | 1.11 (0.95, 1.31) | 736 (8.9) | 0.84 (0.74, 0.96) | / | / |

| Preeclampsia † | 223 (4.9) | Reference | 155 (5.4) | 1.21 (0.97, 1.50) | 336 (4.0) | 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) | / | / |

| Preterm birth | 591 (13.1) | Reference | 310 (10.9) | 0.90 (0.78, 1.05) | 134 (14.6) | 1.19 (0.97, 1.46) | 694 (9.4) | 0.67 (0.59, 0.76) |

| Macrosomia | 792 (17.5) | Reference | 433 (15.2) | 0.89 (0.77, 1.02) | 171 (18.6) | 1.09 (0.91, 1.32) | 1236 (16.7) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.03) |

| SGA ‡ | 309 (8.1) | Reference | 103 (5.5) | 0.72 (0.57, 0.91) | 44 (5.7) | 0.72 (0.52, 1.01) | 401 (6.0) | 0.74 (0.63, 0.87) |

| LGA ‡ | 758 (19.8) | Reference | 401 (21.6) | 1.03 (0.89, 1.19) | 158 (20.6) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.27) | 1191 (17.7) | 0.88 (0.79, 0.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study in China. Nutrients 2026, 18, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010081

Zhang M, Yu H, Li H, Zhou Y, Liu J. Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study in China. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mingxuan, Hongzhao Yu, Hongtian Li, Yubo Zhou, and Jianmeng Liu. 2026. "Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study in China" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010081

APA StyleZhang, M., Yu, H., Li, H., Zhou, Y., & Liu, J. (2026). Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study in China. Nutrients, 18(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010081