The Relationship Between Short-Chain Fatty Acid Secretion and Polymorphisms rs3894326 and rs778986 of the FUT3 Gene in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—An Exploratory Analysis

Abstract

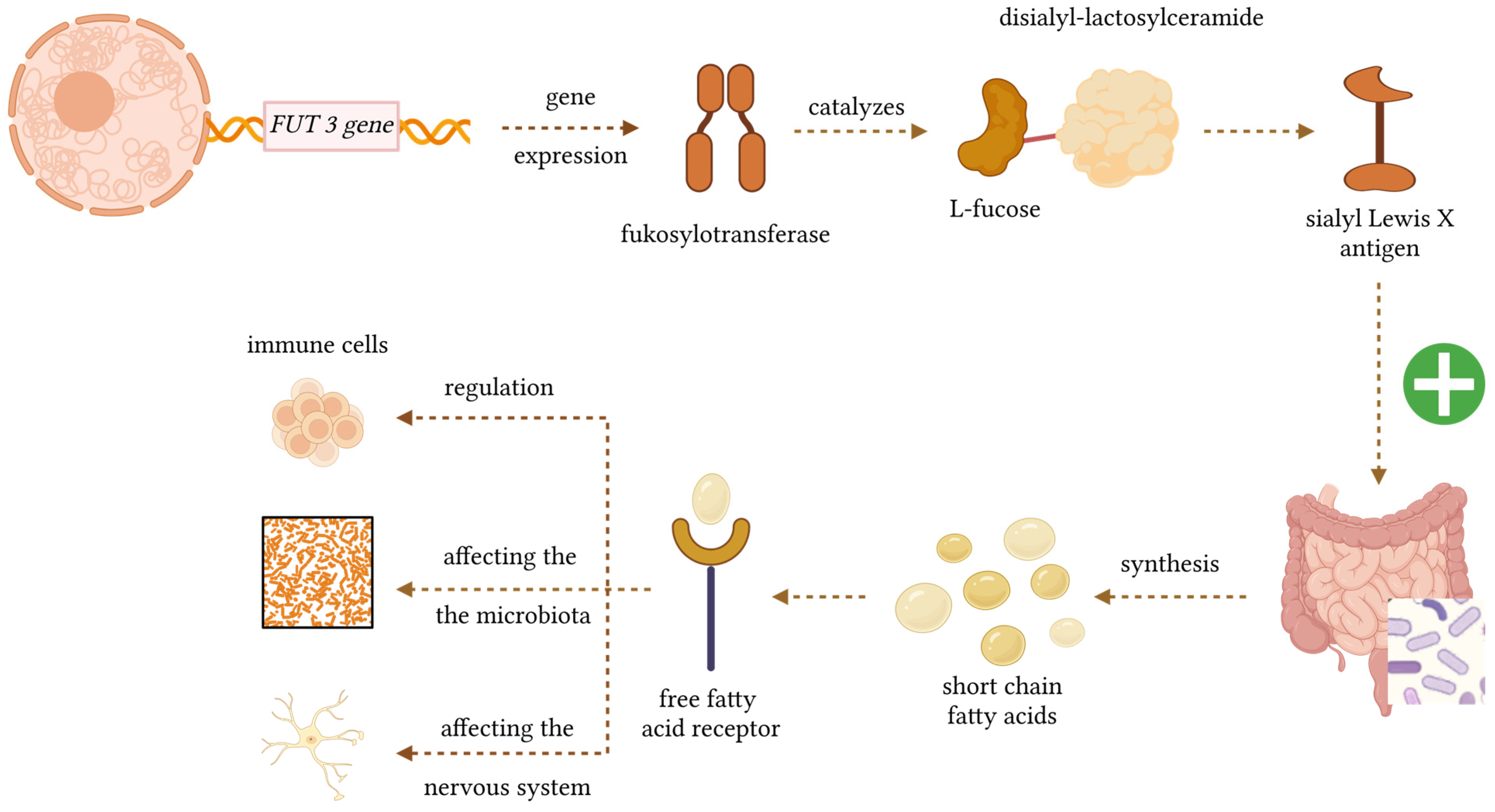

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Group

2.2. DNA Isolation

2.3. Identification of the Studied Polymorphisms

- 1 μL genomic DNA;

- 5 μL TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA);

- 3.75 μL PCR Grade Water (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA);

- 0.25 μL TaqMan probe (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA).

- Pre-incubation (1 cycle): 300 s—95 °C.

- 2-step amplification (50 cycles):

- 95 °C × 15 s;

- 60 °C × 60 s.

2.4. SCFA Isolation

- Acetic acid C2;

- Propionic acid C3;

- Butyric acid C4;

- Valeric acid C5;

- Caproic acid C6.

2.5. SCFA Analysis

- C2—0.82 nM/mg;

- C3—0.51 nM/mg;

- C4—0.26 nM/mg;

- C5—0.22 nM/mg;

- C6—0.17 nM/mg.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Genotyping

3.3. Analysis of SCFA Concentrations and Percentages in Patients

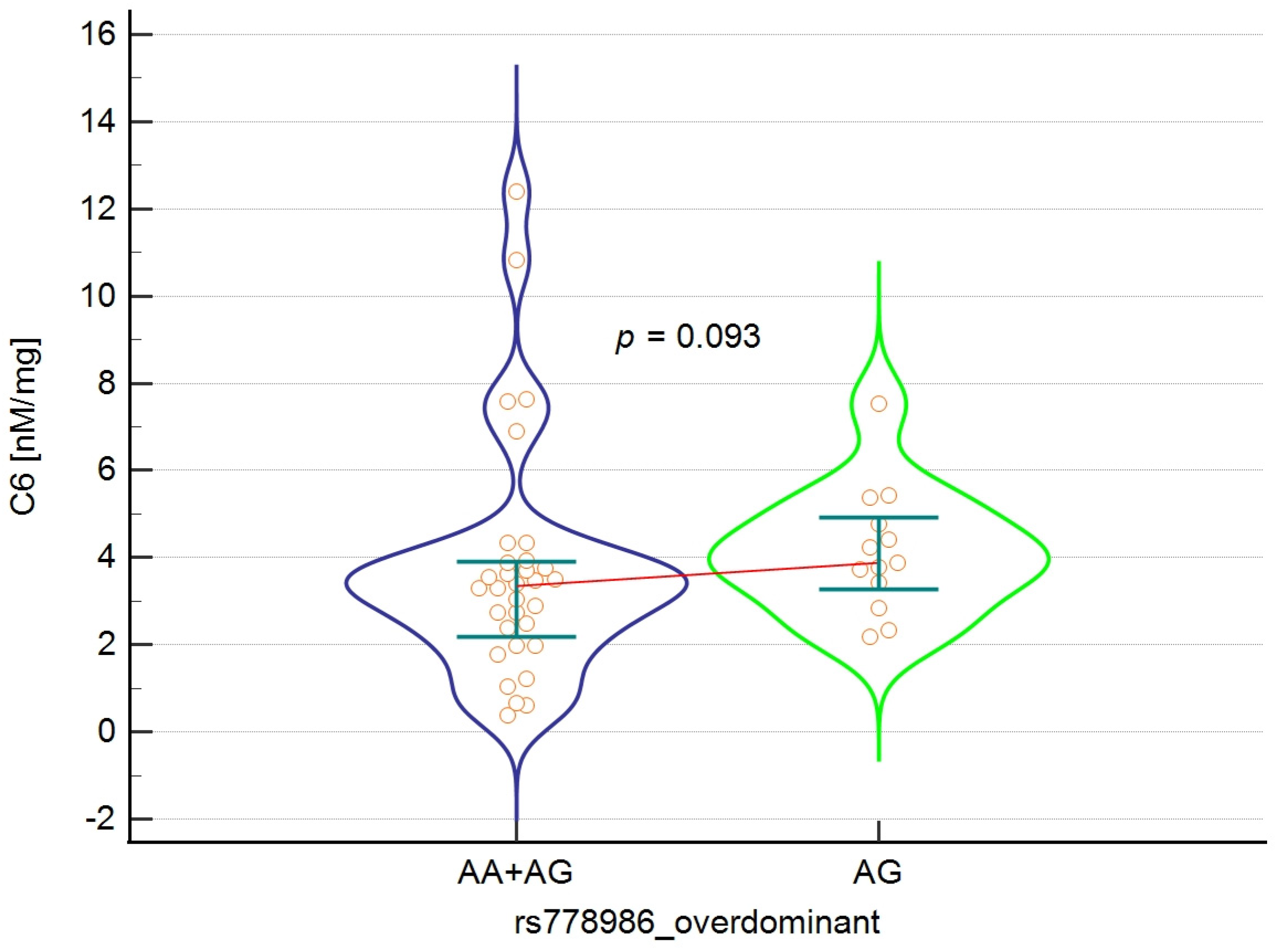

3.4. Analysis of the Relationship Between the rs778986 Polymorphism of the FUT3 Gene and the Concentration and Percentage of SCFA in the Study Group

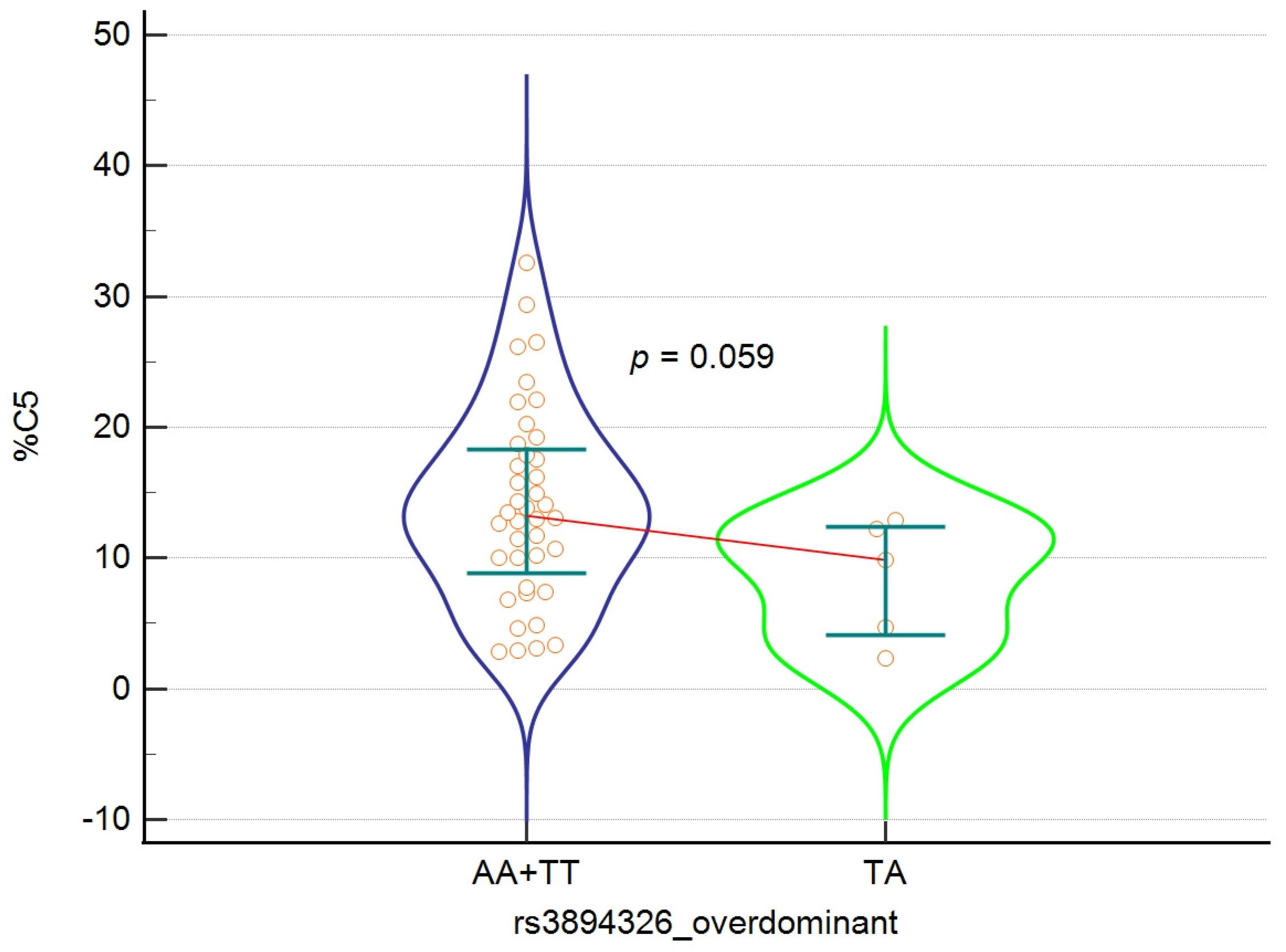

3.5. Analysis of the Relationship Between the rs3894326 Polymorphism of the FUT3 Gene and the Concentration and Percentage of SCFA in the Study Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhee, S.H.; Pothoulakis, C.; Mayer, E.A. Principles and Clinical Implications of the Brain–Gut–Enteric Microbiota Axis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 6, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, W.; Rył, A.; Mizerski, A.; Walczakiewicz, K.; Sipak, O.; Laszczyńska, M. Immunomodulatory Potential of Gut Microbiome-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs). Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of Propionate and Butyrate by the Human Colonic Microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.W.; Takayama, S.; Schultz, J.; Wong, C.H. Mechanism and Specificity of Human Alpha-1,3-Fucosyltransferase V. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 11183–11195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, M.; Panicot-Dubois, L.; Crotte, C.; Sbarra, V.; Lombardo, D.; Sadoulet, M.O.; Mas, E. Peritoneal Colonization by Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells Is Inhibited by Antisense FUT3 Sequence. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 88, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishihara, S.; Narimatsu, H.; Iwasaki, H.; Yazawa, S.; Akamatsu, S.; Ando, T.; Seno, T.; Narimatsu, I. Molecular Genetic Analysis of the Human Lewis Histo-Blood Group System. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 29271–29278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiong, W.; Obara, S.; Abo, H.; Nakatsukasa, H.; Kawashima, H. Prevention of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Targeting 6-Sulfo Sialyl Lewis X Glycans Involved in Lymphocyte Homing. Int. Immunol. 2024, 36, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, T.; Lacroix, C.; Braegger, C.; Chassard, C. Impact of Human Milk Bacteria and Oligosaccharides on Neonatal Gut Microbiota Establishment and Gut Health. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononova, S.V. How Fucose of Blood Group Glycotopes Programs Human Gut Microbiota. Biochemistry 2017, 82, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipplinger, M.; Mink, S.; Bublitz, M.; Gassner, C. Regulation of the Lewis Blood Group Antigen Expression: A Literature Review Supplemented with Computational Analysis. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2024, 51, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, G.; Shevlyakova, M.; Charpagne, A.; Marquis, J.; Vogel, M.; Kirsten, T.; Kiess, W.; Austin, S.; Sprenger, N.; Binia, A. Time of Lactation and Maternal Fucosyltransferase Genetic Polymorphisms Determine the Variability in Human Milk Oligosaccharides. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 574459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, D.R.; Sumner, S.C. Human Microbiota, Blood Group Antigens, and Disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2018, 10, e1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononova, S.; Litvinova, E.; Vakhitov, T.; Skalinskaya, M.; Sitkin, S. Acceptive Immunity: The Role of Fucosylated Glycans in Human Host-Microbiome Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Mozo, M.I.; López-Mecández, D.; Villar, L.M.; Costa-Frossard, L.; Villarrubia, N.; Aladro, Y.; Pilo, B.; Montalbán, X.; Comabella, M.; Casanova-Peño, I.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Multiple Sclerosis: Associated with Disability, Number of T2 Lesions, and Inflammatory Profile. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025, 12, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krištić, J.; Lauc, G. The Importance of IgG Glycosylation—What Did We Learn after Analyzing over 100,000 Individuals. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 328, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, M.-W.; Fu, S.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.-W.; Sytwu, H.-K. The Modulatory Roles of N-Glycans in T-Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, D.; Shoji, H.; Duan, C.; Zhang, G.; Isaji, T.; Wang, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Gu, J. Deficiency of A1,6-Fucosyltransferase Promotes Neuroinflammation by Increasing the Sensitivity of Glial Cells to Inflammatory Mediators. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetko, A.; Kifer, D.; Gornik, O.; Klarić, L.; Visser, E.; Lauc, G.; Wilson, J.F.; Štambuk, T. Glycosylation Alterations in Multiple Sclerosis Show Increased Proinflammatory Potential. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xiao, B.; Luo, Z. Glycosylation in Neuroinflammation: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2025, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-Altering Microorganisms: The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Brain and Behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the Human Gut Microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Chen, T.; Cai, J.; Liu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, X. The Microbiome–Gut–Brain Axis, a Potential Therapeutic Target for Substance-Related Disorders. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 738401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, L.; Delgado, S.; Gorostidi-Aicua, M.; Sepúlveda, L.; Alberro, A.; Iparraguirre, L.; Suárez, J.A.; Romarate, L.; Arruti, M.; Muñoz-Culla, M.; et al. Microbial Dysbiosis and Lack of SCFA Production in a Spanish Cohort of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 960761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, S.; Peferoen, L.A.N.; Vogel, D.Y.S.; Breur, M.; van der Valk, P.; Baker, D.; van Noort, J.M. Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases—An Update. Immunology 2014, 142, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendeln, A.-C.; Degenhardt, K.; Kaurani, L.; Gertig, M.; Ulas, T.; Jain, G.; Wagner, J.; Häsler, L.M.; Wild, K.; Skodras, A.; et al. Innate Immune Memory in the Brain Shapes Neurological Disease Hallmarks. Nature 2018, 556, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borre, Y.E.; O’Keeffe, G.W.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Microbiota and Neurodevelopmental Windows: Implications for Brain Disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Chang, B.J.; Nam, S.M.; Nahm, S.S.; Lee, J.H. Increased Osteopontin Expression and Mitochondrial Swelling in 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Injured Rat Brains. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2017, 58, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, M.M. Multiple Sclerosis Review. Pharm. Ther. 2012, 37, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chia, N.; Kalari, K.R.; Yao, J.Z.; Novotna, M.; Paz Soldan, M.M.; Luckey, D.H.; Marietta, E.V.; Jeraldo, P.R.; Chen, X.; et al. Multiple Sclerosis Patients Have a Distinct Gut Microbiota Compared to Healthy Controls. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghikia, A.; Jörg, S.; Duscha, A.; Berg, J.; Manzel, A.; Waschbisch, A.; Hammer, A.; Lee, D.-H.; May, C.; Wilck, N.; et al. Dietary Fatty Acids Directly Impact Central Nervous System Autoimmunity via the Small Intestine. Immunity 2015, 43, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, A.C.; Rosenberger, T.A. Increasing Acetyl-CoA Metabolism Attenuates Injury and Alters Spinal Cord Lipid Content in Mice Subjected to Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Neurochem. 2017, 141, 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Noto, D.; Hoshino, Y.; Mizuno, M.; Miyake, S. Butyrate Suppresses Demyelination and Enhances Remyelination. J. Neuroinflam. 2019, 16, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Shao, X.; Xu, C.; Xia, S.; Yu, L.; Jiang, L.; Jin, J.; Lin, X.; Jiang, Y. Associations of FUT2 and FUT3 Gene Polymorphisms with Crohn’s Disease in Chinese Patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29, 1778–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.-J.; Bakker, B.M. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Interplay between Diet, Gut Microbiota, and Host Energy Metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijova, E.; Chmelarova, A. Short Chain Fatty Acids and Colonic Health. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2007, 108, 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, J.H.; Pomare, E.W.; Branch, W.J.; Naylor, C.P.; Macfarlane, G.T. Short Chain Fatty Acids in Human Large Intestine, Portal, Hepatic and Venous Blood. Gut 1987, 28, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, H.J. Role of Colonic Short-Chain Fatty Acid Transport in Diarrhea. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-H.; Jeong, I.H.; Hyun, J.-S.; Kong, B.S.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.J. Metabolomic Profiling of CSF in Multiple Sclerosis and Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, I.L.; Federico, F.; Trojano, M.; Tortorella, C.; Liguori, M.; Giannini, P.; Picciola, E.; Natile, G.; Livrea, P. High Resolution Proton MR Spectroscopy of Cerebrospinal Fluid in MS Patients. Comparison with Biochemical Changes in Demyelinating Plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996, 144, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Gong, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis and Lack of Short Chain Fatty Acids in a Chinese Cohort of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 129, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saresella, M.; Marventano, I.; Barone, M.; La Rosa, F.; Piancone, F.; Mendozzi, L.; d’Arma, A.; Rossi, V.; Pugnetti, L.; Roda, G.; et al. Alterations in Circulating Fatty Acid Are Associated with Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.J.M.; Lo, Y.-H.; Mah, A.T.; Kuo, C.J. The Intestinal Stem Cell Niche: Homeostasis and Adaptations. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, N.; Kraiczy, J.; Shivdasani, R.A. Cellular and Molecular Architecture of the Intestinal Stem Cell Niche. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Lu, T.; Wu, J.; Fan, D.; Liu, B.; Zhu, X.; Guo, H.; Du, Y.; Liu, F.; Tian, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Drives Macrophage-Dependent Self-Renewal of Intestinal Stem Cells via Niche Enteric Serotonergic Neurons. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Park, J.; Kim, M. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids, T Cells, and Inflammation. Immune Netw. 2014, 14, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordoñez-Rodriguez, A.; Roman, P.; Rueda-Ruzafa, L.; Campos-Rios, A.; Cardona, D. Changes in Gut Microbiota and Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otite, S.V.; Lag-Brotons, A.J.; Ezemonye, L.I.; Martin, A.D.; Pickup, R.W.; Semple, K.T. Volatile Fatty Acids Effective as Antibacterial Agents against Three Enteric Bacteria during Mesophilic Anaerobic Incubation. Molecules 2024, 29, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinelli, V.; Biscotti, P.; Martini, D.; Del Bo’, C.; Marino, M.; Meroño, T.; Nikoloudaki, O.; Calabrese, F.M.; Turroni, S.; Taverniti, V.; et al. Effects of Dietary Fibers on Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Gut Microbiota Composition in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vich Vila, A.; Collij, V.; Sanna, S.; Sinha, T.; Imhann, F.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Mujagic, Z.; Jonkers, D.M.A.E.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Fu, J.; et al. Impact of Commonly Used Drugs on the Composition and Metabolic Function of the Gut Microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Polymorphism | Inheritance Model | Genotype | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUT3 rs778986 n = 45 | Codominant | AA | 1 | 2.2% |

| AG | 13 | 28.9% | ||

| GG | 31 | 68.9% | ||

| Dominant | GG | 31 | 68.9% | |

| AA+AG | 14 | 31.1% | ||

| Overdominant | AA+GG | 32 | 71.1% | |

| AG | 13 | 28.9% | ||

| Recessive | AA | 1 | 2.2% | |

| AG+GG | 44 | 97.8% | ||

| FUT3 rs3894326 n = 46 | Codominant | AA | 40 | 87.0% |

| AT | 5 | 10.9% | ||

| TT | 1 | 2.1% | ||

| Dominant | TT | 1 | 2.1% | |

| AA+AT | 45 | 97.9% | ||

| Overdominant | AA+TT | 41 | 89.1% | |

| AT | 5 | 10.9% | ||

| Recessive | AA | 40 | 87.0% | |

| AT+TT | 6 | 13.0% |

| FUT3 rs778986 | A (%) | G (%) | P | χ2 |

| Study group | 15 (16.7%) | 75 (83.3%) | 0.857 | 0.033 |

| The 1000 Genomes Project | 362 (18.0%) | 1650 (82.0%) | ||

| FUT3 rs3894326 | A (%) | T (%) | P | χ2 |

| Study group | 85 (92.4%) | 7 (7.6%) | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| The 1000 Genomes Project | 1851 (92.0%) | 161 (8.0%) |

| nM/mg | N | Min | Max | M | Me | SD | 2.5–97.5 P |

| Acetic acid C2 | 47 | 5.69 | 76.47 | 38.45 | 38.60 | 15.47 | 10.49–72.24 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 47 | 3.73 | 46.03 | 14.05 | 12.69 | 9.03 | 3.92–44.38 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 47 | 5.03 | 113.61 | 28.15 | 22.25 | 22.25 | 5.72–108.25 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 47 | 2.31 | 44.65 | 12.28 | 9.94 | 8.33 | 2.44–34.66 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 47 | 0.37 | 12.41 | 3.90 | 3.49 | 2.47 | 0.53–11.34 |

| Total SCFA in samples | 47 | 31.61 | 260.84 | 96.82 | 90.88 | 44.66 | 33.09–247.74 |

| % | N | Min | Max | M | Me | SD | 2.5–97.5 P |

| Acetic acid C2 | 47 | 6.41 | 65.51 | 41.07 | 41.60 | 9.81 | 19.74–60.46 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 47 | 5.18 | 37.97 | 14.46 | 14.41 | 5.50 | 6.52–30.39 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 47 | 9.13 | 51.47 | 26.95 | 25.07 | 9.51 | 11.08–48.49 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 47 | 2.32 | 32.56 | 13.31 | 12.91 | 7.26 | 2.70–30.39 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 47 | 0.52 | 10.09 | 4.22 | 3.91 | 2.14 | 0.75–9.72 |

| [nM/mg] | Dominant rs778986 = “GG” | Dominant rs778986 = “AA+AG” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 31 | 39.91 | 13.07–68.31 | 14 | 38.56 | 5.69–76.47 | 0.845 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 31 | 11.42 | 3.81–42.30 | 14 | 12.84 | 5.91–46.03 | 0.980 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 31 | 21.91 | 5.31–100.31 | 14 | 23.32 | 7.76–105.6 | 0.641 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 31 | 9.29 | 2.36–39.29 | 14 | 13.03 | 5.1–29.85 | 0.186 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 31 | 3.41 | 0.44–11.97 | 14 | 3.83 | 2.18–7.54 | 0.170 |

| Total SCFA in samples | 31 | 92.58 | 32.21–222.60 | 14 | 88.98 | 39.49–260.84 | 0.941 |

| % | Dominant rs778986 = “GG” | Dominant rs778986 = “AA+AG” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 31 | 41.60 | 26.96–63.45 | 14 | 41.88 | 6.41–55.46 | 0.902 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 31 | 13.30 | 5.72–34.89 | 14 | 14.69 | 9.11–17.65 | 0.825 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 31 | 25.16 | 9.92–50.26 | 14 | 25.03 | 19.56–46.64 | 0.864 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 31 | 11.71 | 2.47–31.67 | 14 | 13.52 | 4.89–26.18 | 0.281 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 31 | 3.75 | 0.61–9.40 | 14 | 4.337 | 1.07- 9.54 | 0.281 |

| [nM/mg] | Overdominant rs778986 = “AG” | Overdominant rs778986 = “AA+GG” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 13 | 38.60 | 5.69–76.47 | 32 | 39.02 | 13.09–68.13 | 1 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 13 | 12.87 | 5.91–46.03 | 32 | 11.32 | 3.82–42.19 | 0.841 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 13 | 24.35 | 7.76–105.66 | 32 | 21.58 | 5.34–99.10 | 0.499 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 13 | 13.08 | 5.11–29.85 | 32 | 9.40 | 2.36–38.80 | 0.193 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 13 | 3.88 | 2.18–7.54 | 32 | 3.35 | 0.44–11.93 | 0.093 |

| Total SCFA in samples | 13 | 89.24 | 39.49–260.84 | 32 | 91.73 | 32.26–220.89 | 0.764 |

| % | Overdominant rs778986 = “AG” | Overdominant rs778986 = “AA+GG” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 13 | 40.87 | 6.41–55.46 | 32 | 41.62 | 27.03–63.26 | 0.764 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 13 | 14.97 | 9.11–17.65 | 32 | 12.99 | 5.77–34.61 | 0.707 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 13 | 24.98 | 19.56–46.64 | 32 | 25.36 | 10.00–50.15 | 0.900 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 13 | 12.95 | 4.89–26.18 | 32 | 12.18 | 2.49–31.59 | 0.341 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 13 | 4.53 | 1.09–9.54 | 32 | 3.70 | 0.62–9.34 | 0.211 |

| [nM/mg] | Recessive rs3894326 = “AA” | Recessive rs3894326 = “AA” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 40 | 38.33 | 9.25–71.37 | 6 | 39.41 | 24.06–63.30 | 0.7941 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 40 | 11.32 | 3.87–44.81 | 6 | 12.78 | 5.57–16.87 | 0.625 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 40 | 22.08 | 5.54–84.97 | 6 | 23.00 | 13.80–65.24 | 0.493 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 40 | 10.01 | 2.52–37.25 | 6 | 9.01 | 2.50–17.09 | 0.514 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 40 | 3.524 | 0.49–9.60 | 6 | 3.11 | 1.22–12.41 | 0.794 |

| Total SCFA in samples | 40 | 90.80 | 32.70–210.76 | 6 | 87.01 | 62.60–172.95 | 0.922 |

| % | Recessive rs3894326 = “AA” | Recessive rs3894326 = “AA” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 40 | 41.74 | 16.29–61.77 | 6 | 39.49 | 33.05–50.01 | 0.819 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 40 | 14.29 | 7.17–32.36 | 6 | 12.46 | 5.18–20.27 | 0.625 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 40 | 24.99 | 10.57–46.53 | 6 | 28.09 | 21.73–51.47 | 0.282 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 40 | 13.27 | 2.89–30.95 | 6 | 11.05 | 2.32–22.09 | 0.240 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 40 | 4.03 | 0.69–9.82 | 6 | 3.41 | 1.32–7.17 | 0.602 |

| [nM/mg] | Overdominant rs3894326 = “TA” | Overdominant rs3894326 = “AA+TT” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 5 | 40.22 | 26.04–63.30 | 41 | 38.14 | 9.42–71.11 | 0.407 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 5 | 12.87 | 5.57–16.87 | 41 | 11.23 | 3.88–44.75 | 0.986 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 5 | 23.85 | 13.80–65.24 | 41 | 22.14 | 5.56–83.94 | 0.448 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 5 | 8.08 | 2.50–17.09 | 41 | 10.30 | 2.54–36.88 | 0.282 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 5 | 2.33 | 1.22–12.41 | 41 | 3.56 | 0.50–9.54 | 0.584 |

| Total SCFA in samples | 5 | 92.58 | 62.60–172.95 | 41 | 90.72 | 32.76–208.26 | 0.659 |

| % | Overdominant rs3894326 = “TA” | Overdominant rs3894326 = “AA+TT” | P | ||||

| N | Me | IQR | N | Me | IQR | ||

| Acetic acid C2 | 5 | 41.60 | 36.60–50.01 | 41 | 41.63 | 16.78–61.58 | 0.764 |

| Propionic acid C3 | 5 | 15.80 | 5.18–20.27 | 41 | 14.17 | 7.17–32.08 | 0.958 |

| Butyric acid C4 | 5 | 25.76 | 21.73–51.47 | 41 | 24.99 | 10.64–46.52 | 0.448 |

| Valeric acid C5 | 5 | 9.88 | 2.32–12.91 | 41 | 13.48 | 2.89–30.87 | 0.059 |

| Caproic acid C6 | 5 | 3.17 | 1.32–7.17 | 41 | 4.14 | 0.70–9.80 | 0.315 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kulaszyńska, M.; Czarnecka, W.; Jakubiak, N.; Styburski, D.; Sowiński, M.; Czapla, N.; Stachowska, E.; Koziarska, D.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K. The Relationship Between Short-Chain Fatty Acid Secretion and Polymorphisms rs3894326 and rs778986 of the FUT3 Gene in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—An Exploratory Analysis. Nutrients 2026, 18, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010062

Kulaszyńska M, Czarnecka W, Jakubiak N, Styburski D, Sowiński M, Czapla N, Stachowska E, Koziarska D, Skonieczna-Żydecka K. The Relationship Between Short-Chain Fatty Acid Secretion and Polymorphisms rs3894326 and rs778986 of the FUT3 Gene in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—An Exploratory Analysis. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulaszyńska, Monika, Wiktoria Czarnecka, Natalia Jakubiak, Daniel Styburski, Mateusz Sowiński, Norbert Czapla, Ewa Stachowska, Dorota Koziarska, and Karolina Skonieczna-Żydecka. 2026. "The Relationship Between Short-Chain Fatty Acid Secretion and Polymorphisms rs3894326 and rs778986 of the FUT3 Gene in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—An Exploratory Analysis" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010062

APA StyleKulaszyńska, M., Czarnecka, W., Jakubiak, N., Styburski, D., Sowiński, M., Czapla, N., Stachowska, E., Koziarska, D., & Skonieczna-Żydecka, K. (2026). The Relationship Between Short-Chain Fatty Acid Secretion and Polymorphisms rs3894326 and rs778986 of the FUT3 Gene in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis—An Exploratory Analysis. Nutrients, 18(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010062