Psychological and Psychiatric Consequences of Prolonged Fasting: Neurobiological, Clinical, and Therapeutic Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria (Pre-Specified)

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

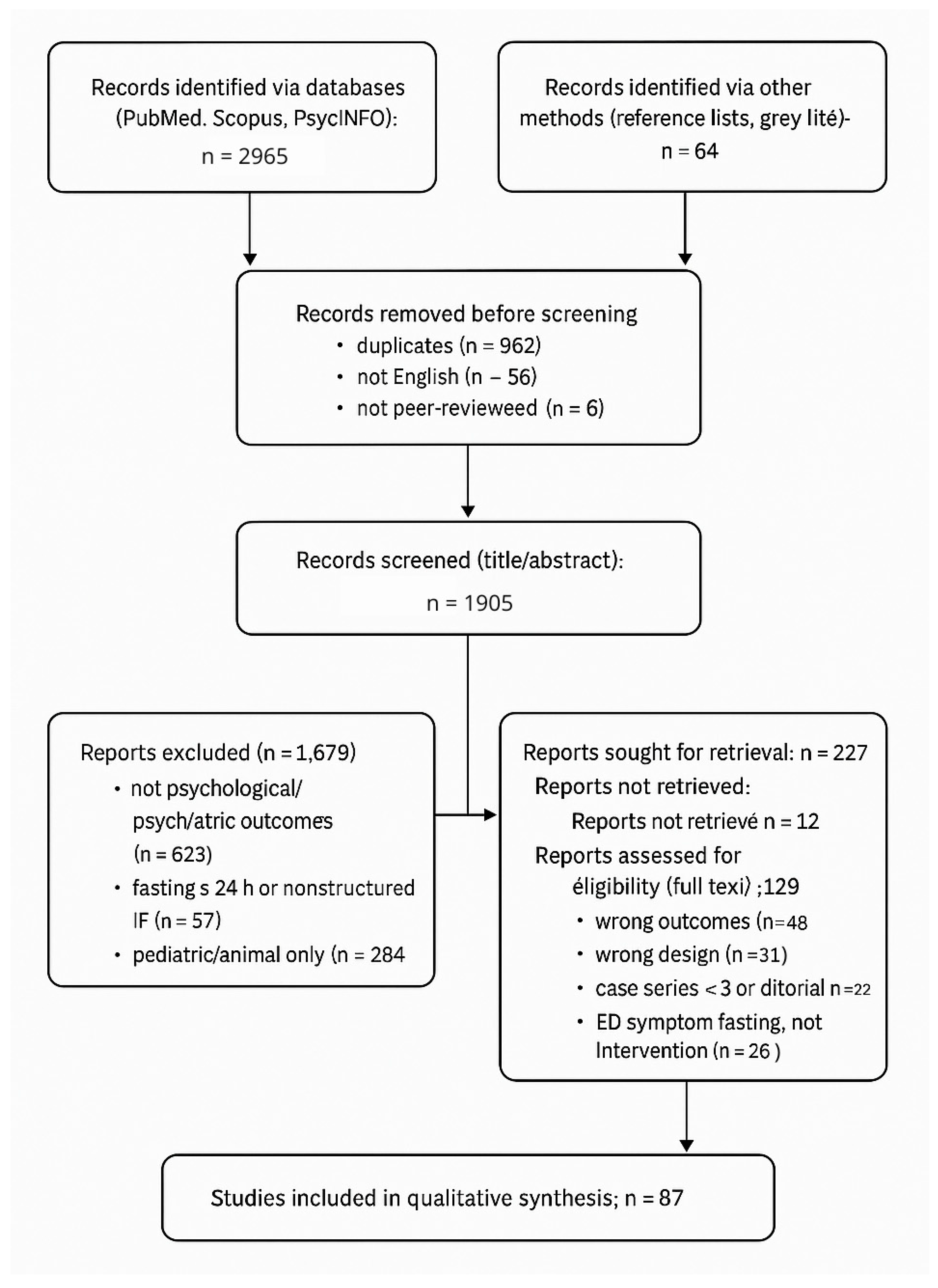

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Human Studies

3.3. Synthesis of Human Outcomes

3.4. Synthesis of Preclinical Mechanisms

4. Neurobiological and Neurochemical Effects of Prolonged Fasting

4.1. Ketone Signaling and Neurotransmission

4.2. Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Autophagy

4.3. Neuroendocrine and Autonomic Recalibration

4.4. Gut–Brain Axis Modulation

4.5. Immuno-Oxidative Landscape

5. Psychological Outcomes

5.1. Mood

5.2. Anxiety

5.3. Stress Correlations

5.4. Religious Fasting

5.5. Severe Adverse Events

5.5.1. Eating Disorders

5.5.2. Psychosis

6. Clinical Integration and Ethical Considerations

6.1. Therapeutic Fasting in Psychiatric Populations

- Initial assessment (week 0): Psychiatric history; current diagnoses; ED screening; suicidality; medications; metabolic panel (electrolytes, glucose/ketones if applicable); BMI and weight trajectory; sleep and caffeine use.

- Protocol start: For at-risk patients, prefer ≤14 h fasting windows; maintain consistent sleep timing; avoid abrupt medication schedule changes.

- Follow-up (every 2 weeks): Clinician-rated scales (e.g., HDRS-17, CGI-S/CGI-I), self-report (PHQ-9/GAD-7/PSS), adverse-event checklist (psychiatric and somatic), weight/BMI, basic labs if indicated.

- Discontinuation criteria (“STOP”): ≥5% weight loss in <4 weeks, emergent suicidality, psychotic or manic symptoms, severe anxiety/agitation, electrolyte derangements, or clinically significant sleep disruption non-responsive to adjustments.

- Coordination: Multidisciplinary oversight (psychiatry, nutrition/dietetics, internal medicine/endocrinology), with shared decision-making and informed consent emphasizing uncertain long-term efficacy.

6.2. Ethical and Clinical Governance

7. Research Gaps and Future Directions

- (1)

- Protocol standardization. Heterogeneous fasting windows (12–72 h), feeding macronutrient composition, and cycle duration hinder comparability; consensus statements mirroring exercise prescription guidelines are needed.

- (2)

- Psychiatric stratification. Forthcoming trials should stratify by diagnostic category, illness phase, and psychotropic medication to delineate differential risk–benefit profiles.

- (3)

- Long-term safety and efficacy. Most studies last ≤12 weeks; prospective cohorts ≥12 months are crucial to detect delayed metabolic, endocrine, or affective sequelae.

- (4)

- Mechanistic biomarkers. Integrative omics (metabolomics, epigenomics), inflammatory panels, and digital phenotyping of mood/sleep could clarify mediators and moderators of response.

- (5)

- Gut–brain axis. Controlled feeding studies isolating fiber and prebiotic intake will determine how microbiota shifts contribute to affective and cognitive outcomes.

- (6)

- Sex and age effects. Given hormonal modulation of HPA and reward circuitry, sex-specific and developmental-stage analyses are imperative.

- (7)

- Digital-assisted monitoring. Wearable glucose/ketone sensors and app-based mood tracking may enhance safety and adherence, yet require validation in psychiatric samples.

- (8)

- Expectancy bias mitigation. Employ blinded outcome assessors, neutral framing, and objective biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory panels, HRV, digital sleep metrics) to reduce expectancy and measurement biases.

- (9)

- Standardized adverse-event reporting. Adopt validated psychiatric terminology and structured AE taxonomies with severity/relatedness grading, enabling cross-study comparability and safety-signal detection.

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| IF | Intermittent Fasting |

| TRE | Time-Restricted Eating |

| ADF | Alternate-Day Fasting |

| RRF | Religious/Ritual Fasting |

| BHB | β-Hydroxybutyrate |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (axis) |

| HCA2 | Hydroxycarboxylic Acid Receptor 2 (HCAR2; GPR109A) |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| HDRS-17 | 17-Item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| STAI-S | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State subscale |

| PPF | Periodic Prolonged Fasting |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNFα | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| IL1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| H3 | Histone H3 |

| PGC1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| ULK1 | Unc-51-Like Autophagy-Activating Kinase 1 |

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ED | Eating Disorder |

| CREB-PGC | cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein–PGC-1 Axis |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and Pyrin Domain-Containing Protein 3 (Inflammasome) |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| REM | Rapid Eye Movement |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| TRF | Time-Restricted Feeding |

| HRV | Heart-Rate Variability |

| FMD | Fasting-Mimicking Diet |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| CAPS-5 | Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CNS | Central Nervous System. |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha |

References

- Koppold, D.A.; Breinlinger, C.; Hanslian, E.; Kessler, C.; Cramer, H.; Khokhar, A.R.; Peterson, C.M.; Tinsley, G.; Vernieri, C.; Bloomer, R.J.; et al. International consensus on fasting terminology. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1779–1794.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Panda, S. Fasting, circadian rhythms, and time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cabo, R.; Mattson, M.P. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervenka, M.C.; Wood, S.; Bagary, M.; Balabanov, A.; Bercovici, E.; Brown, M.-G.; Devinsky, O.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Doherty, C.P.; Felton, E.; et al. International recommendations for the management of adults treated with ketogenic diet therapies. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2021, 11, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, T.; Hirschey, M.D.; Newman, J.; He, W.; Shirakawa, K.; Le Moan, N.; Grueter, C.A.; Lim, H.; Saunders, L.R.; Stevens, R.D.; et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science 2013, 339, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, R.M.; Guo, Z.; de Cabo, R.; Iyun, T.; Rios, M.; Hagepanos, A.; Ingram, D.K.; Lane, M.A.; Mattson, M.P. Intermittent fasting dissociates beneficial effects of dietary restriction on glucose metabolism and neuronal resistance to injury from calorie intake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6216–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.W.; Yu, B.P. The inflammation hypothesis of aging: Molecular modulation by calorie restriction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 928, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, A.A.; Esmaeili, R.; Ganji, G. The impact of fasting on the psychological well-being of Muslim graduate students. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 3270–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienfuegos, S.; Gabel, K.; Kalam, F.; Ezpeleta, M.; Pavlou, V.; Lin, S.; Wiseman, E.; Varady, K.A. The effect of 4-h versus 6-h time restricted feeding on sleep quality, duration, insomnia severity and obstructive sleep apnea in adults with obesity. Nutr. Health 2022, 28, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Rodgers, R.F.; Murray, S.B.; Nagata, J.M. Prevalence and demographic, substance use, and mental health correlates of fasting among U.S. college students. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Hong, N.; Kim, K.W.; Cho, S.J.; Lee, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Kang, E.S.; Lee, B.W.; Kim, J.; Jang, H.C.; et al. The Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting to Reduce Body Mass Index and Glucose Metabolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solianik, R.; Sujeta, A. Two-Day Fasting Evokes Stress, but Does Not Affect Mood, Brain Activity, Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Motor Performance in Overweight Women. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 338, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelmi de Toledo, F.; Grundler, F.; Bergouignan, A.; Drinda, S.; Michalsen, A. Safety, Health Improvement and Well-Being during a 4 to 21-Day Fasting Period in an Observational Study Including 1422 Subjects. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmi de Toledo, F.; Grundler, F.; Sirtori, C.R.; Ruscica, M. Unravelling the Health Effects of Fasting: A Long Road from Obesity Treatment to Healthy Life Span Increase and Improved Cognition. Ann. Med. 2020, 52, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Hay, P.; Schmidt, U. Anorexia Nervosa: Aetiology, Assessment, and Treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanaki, C.; Rodopaios, N.E.; Koulouri, A.; Pliakas, T.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Vasara, E.; Skepastianos, P.; Serafeim, T.; Boura, I.; Dermitzakis, E. The Christian Orthodox Church fasting diet is associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety and a better cognitive performance in middle life. Nutrients 2021, 13, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.A.; Latief, M.; Manuel, S.; Shashikiran, K.B.; Dwivedi, R.; Prasad, D.K.; Golla, A.; Raju, S.B. Impact of Fasting during Ramadan on Renal Functions in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Indian J. Nephrol. 2022, 32, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, H.; Beyl, R.A.; Della Manna, D.L.; Yang, E.S.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Affects Markers of the Circadian Clock, Aging, and Autophagy in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Cienfuegos, S.; Ezpeleta, M.; Gabel, K.; Pavlou, V.; Mulas, A.; Chakos, K.; McStay, M.; Wu, J.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.; et al. Time-Restricted Eating Without Calorie Counting for Weight Loss in a Racially Diverse Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniaci, G.; La Cascia, C.; Giammanco, A.; Ferraro, L.; Chianetta, R.; Di Peri, R.; Sardella, Z.; Citarrella, R.; Mannella, Y.; Larcan, S.; et al. Efficacy of a Fasting-Mimicking Diet in Functional Therapy for Depression: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddahby, S.; Kadri, N.; Moussaoui, D. Fasting during Ramadan Is Associated with a Higher Recurrence Rate in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Kroeger, C.M.; Barnosky, A.; Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Hoddy, K.K.; Gabel, K.; Freels, S.; Rigdon, J.; Rood, J.; et al. Effect of alternate-day fasting on weight loss, weight maintenance, and cardioprotection among metabolically healthy obese adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, C.; Wu, R.; Wu, M.; Liu, W.; Dai, Z.; Li, Y. How Experiences Affect Psychological Responses During Supervised Fasting: A Preliminary Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 651760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, Y.-H.; Nguyen, K.Y.; Grant, R.W.; Goldberg, E.L.; Bodogai, M.; Kim, D.; D’Agostino, D.; Planavsky, N.; Lupfer, C.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; et al. The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome–mediated inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalska, P.; Crawford, P.A. Multi-dimensional roles of ketone bodies in fuel metabolism, signaling, and therapeutics. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.C.; Verdin, E. Ketone bodies as signaling metabolites. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudkoff, M.; Daikhin, Y.; Horyn, O.; Nissim, I.; Nissim, I. Ketosis and brain handling of glutamate, glutamine, and GABA. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurak, N.; Günther, A.; Grau, F.S.; Muth, E.R.; Pustovoyt, M.; Bischoff, S.C.; Zipfel, S.; Enck, P. Effects of a 48-h fast on heart rate variability and cortisol levels in healthy female subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Drori, S.; Uldry, M.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Rhee, J.; Jäger, S.; Handschin, C.; Zheng, K.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; et al. Suppression of Reactive Oxygen Species and Neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 Transcriptional Coactivators. Cell 2006, 127, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirezaei, M.; Kemball, C.C.; Flynn, C.T.; Wood, M.R.; Whitton, J.L.; Kiosses, W.B. Short-term fasting induces profound neuronal autophagy. Autophagy 2010, 6, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeitler, M.; Lauche, R.; Hohmann, C.; Choi, K.-E.; Schneider, N.; Steckhan, N.; Rathjens, F.; Anheyer, D.; Paul, A.; von Scheidt, C.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Fasting and Lifestyle Modification in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: Effects on Patient-Reported Outcomes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Gambero, A.J.; Sanjuan, C.; Serrano-Castro, P.J.; Suárez, J.; Rodríguez de Fonseca, F. The Biomedical Uses of Inositols: A Nutraceutical Approach to Metabolic Dysfunction in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, F.; Osaili, T.; Obaid, R.S.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H.; Ismail, L.C.; Hasan, H.; Hashim, M.; Alam, I.; Sehar, B. Gut Microbiota and Time-Restricted Feeding/Eating. Nutrients 2023, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braniște, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Tóth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L.G.; Kundu, P.; et al. The Gut Microbiota Influences Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability in Mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 263ra158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host Microbiota Constantly Control Maturation and Function of Microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rominger, C.; Weber, B.; Aldrian, A.; Berger, L.; Schwerdtfeger, A.R. Short-Term Fasting-Induced Changes in Heart Rate Variability Are Associated with Interoceptive Accuracy. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 239, 113558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, M.; Maleki, A.H.; Mojtahedi, S.; Ehsanifar, M.; Rosenkranz, S.K.; Symonds, M.E.; Tarashi, M.S.; Fatolahi, S.; Fernandez, M.L. The Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Inflammatory Markers in Adults: A Systematic Review and Pairwise and Network Meta-Analyses. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Fan, J.; Ge, T.; Tang, L.; Li, B. The Mechanism of Acute Fasting-Induced Antidepressant-Like Effects in Mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgren, J.; Daniilidou, M.; Kåreholt, I.; Sindi, S.; Akenine, U.; Nordin, K.; Rosenborg, S.; Ngandu, T.; Kivipelto, M.; Sandebring-Matton, A. Serum proBDNF Is Associated with Changes in the Ketone Body β-Hydroxybutyrate and Shows Superior Repeatability over Mature BDNF: Secondary Outcomes from a Cross-Over Trial in Healthy Older Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 716594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murta, L.; Seixas, D.; Harada, L.; Damiano, R.F.; Zanetti, M. Intermittent Fasting as a Potential Therapeutic Instrument for Major Depression Disorder: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towers, A.E.; Oelschlager, M.L.; Patel, J.; Gainey, S.J.; McCusker, R.H.; Freund, G.G. Acute Fasting Inhibits Central Caspase-1 Activity Reducing Anxiety-Like Behavior and Increasing Novel Object and Object Location Recognition. Metabolism 2017, 71, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Sui, X.; Guo, Y.; Xin, B.; Guo, Z.; et al. Effects of 10-Day Complete Fasting on Physiological Homeostasis, Nutrition and Health Markers in Male Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domaszewski, P.; Rogowska, A.M.; Żylak, K. Examining Associations Between Fasting Behavior, Orthorexia Nervosa, and Eating Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafidh, K.; Khan, M.; Shaikh, T.G.; Abdurahman, H.; Elamouri, J.; Beshyah, S.A. Review of the Literature on Ramadan Fasting and Health in 2022. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 15, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D.J.; Hernandez, B.; Zeitzer, J.M. Early Time-Restricted Eating Advances Sleep in Late Sleepers: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2023, 19, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Wisco, B.E.; Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking Rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 3, 400–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaginis, C.; Mantzorou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Gialeli, M.; Troumbis, A.Y.; Vasios, G.K. Christian Orthodox Fasting as a Traditional Diet with Low Content of Refined Carbohydrates That Promotes Human Health: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, K.; Giannouli, V. Religious beliefs, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression among Greek Orthodox elders. Anthropological Researches and Studies 2020, 10, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorulmaz, O.; Gençöz, T.; Woody, S. OCD cognitions and symptoms in different religious contexts. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, A.V.; Fobker, M.; Gellner, R.; Knecht, S.; Flöel, A. Caloric restriction improves memory in elderly humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.F.; Beyl, R.; Early, K.S.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early time-restricted feeding improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress even without weight loss in men with prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1212–1221.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Lakhanpal, D.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Kataria, H.; Kaur, M.; Kaur, G. Late-onset intermittent fasting dietary restriction as a potential intervention to retard age-associated brain function impairments in male rats. Age (Dordr.) 2012, 34, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshed, H.; Steger, F.L.; Bryan, D.R.; Richman, J.S.; Warriner, A.H.; Hanick, C.J.; Martin, C.K.; Salvy, S.-J.; Peterson, C.M. Effectiveness of early time-restricted eating for weight loss, fat loss, and cardiometabolic health in adults with obesity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treasure, J.; Duarte, T.A.; Schmidt, U. Eating disorders. Lancet 2020, 395, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Otto, M.W. Efficacy evaluation of exercise as an augmentation strategy to brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: A randomized pilot trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020, 49, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganson, K.T.; Cuccolo, K.; Hallward, L.; Nagata, J.M. Intermittent Fasting: Describing Engagement and Associations with Eating-Disorder Behaviors and Psychopathology among Canadian Adolescents and Young Adults. Eat. Behav. 2022, 47, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heun, R. A systematic review on the effect of Ramadan on mental health. Glob. Psychiatry 2018, 1, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapel, B.; Fraccarollo, D.; Westhoff-Bleck, M.; Bauersachs, J.; Lichtinghagen, R.; Jahn, K.; Burkert, A.; Buchholz, V.; Bleich, S.; Frieling, H.; et al. Impact of fasting on stress systems and depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | No. of Human Studies | Predominant Designs (n) | Net Direction of Effect | Overall Quality | Representative Studies (Author, Year) | Sample Size/Population | Fasting Protocol | Follow-Up Duration | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood (Depression/Anxiety) | 18 (12 RCT, 6 Obs) | RCT (12), Prospective (3), Cross-sectional (3) | Mixed positive | Moderate | [11,12] | n = 93 adults with MDD; college students | 16:8 IF for 4 weeks; ad lib fasting | 4–8 weeks | ↓ Depression scores; ↑ BDNF; ↑ guilt in perfectionists |

| Cognitive Function | 11 (6 RCT, 5 Obs) | RCT (6), Crossover (2), Cohort (3) | Positive acute; neutral/negative chronic | Moderate | [13] | n = 60 older adults; healthy young/overweight adults | 16:8 IF for 3 months; 48 h water-only fast/TRF | 12 weeks (TRE)/48 h (acute) | ↑ Working memory acutely; mixed effects long-term; sleep changes may blunt mood |

| Stress Physiology/HPA Axis | 9 (4 RCT, 5 Obs) | RCT (4), Cohort (5) | ↓ Basal cortisol, ↑ HRV | Low–Moderate | [14,15] | n = 1422 adults in supervised fasting programs | 10–21 day supervised periodic fasting; TRE variants | 10–21 days | ↓ Cortisol; ↑ HRV; improved stress-system resilience |

| Eating-Disorder Risk | 7 (0 RCT, 7 Obs) | Cross-sectional (5), Cohort (2) | ↑ Restrictive behaviors | Low | [16] | n = 738–8000 college/clinical samples | Varied unsupervised IF and extended fasts | Cross-sectional or 4-week longitudinal | ↑ Restrictive behaviors; relapse risk in vulnerable phenotypes |

| Psychosis/Manic Switch | 4 (0 RCT, 4 Case/Cohort) | Case reports (3), Cohort (1) | Rare but severe exacerbations | Very Low | [17,18] | 3 case reports; one community cohort (n ≈ 1214) | Ramadan/Lent-aligned fasts; prolonged fasts | 2–12 weeks | Rare mania/psychosis during religious or prolonged fasts; supervision advised |

| Study (First Author, Year) | Country | Design | Population/Sample | Clinical Status/Diagnosis | Fasting Protocol (Type and Duration) | Comparator/Control | Psychological/Psychiatric Instruments | Evaluation Method (Clinician-Rated vs. Self-Report) | Follow-Up Duration | Adverse-Event Documentation (Psychiatric/Somatic) | Key Outcomes | Risk of Bias | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | Germany | Observational pre–post cohort (clinic registry) | Adults attending Buchinger Wilhelmi clinics; n = 1422; mixed indications; mean age ~ 56 y; both sexes | General medical outpatients; no primary psychiatric diagnosis required | Buchinger periodic fasting, 4–21 days; ~250–500 kcal/day broths/juices + ≥2.5 L water; light activity | None (within-subject pre–post) | Self-rated emotional/physical well-being; subjective health-complaints log | Self-report | During fast and end-of-fast (up to 21 days) | <1% adverse events recorded; psychiatric AEs not specified | Marked improvements in self-reported well-being | Observational (no control) | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209353 |

| [19] | USA | Randomized clinical trial (parallel-arm) | Adults with obesity; n = 90; mean BMI 39.6; 80% female | Obesity; no severe chronic disease | Early time-restricted eating (07:00–15:00) + energy restriction; 14 weeks | Control eating window (≥12 h) + energy restriction | POMS subscales (fatigue–inertia, vigor–activity, depression–dejection) | Self-report | 14 weeks | Not specified (psychiatric AEs) | Greater improvements in mood indices vs. control; diastolic BP improved | RCT (moderate sample) | https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061234. |

| [20] | USA | Randomized controlled trial (12-month, three-arm; secondary analysis) | Adults with obesity; n = 90; 12-month intervention | Obesity | 8 h TRE (12:00–20:00) without calorie counting; 12 months | Daily calorie restriction (25% ER) and no-intervention control | BDI-II; POMS; SF-36 (Quality of Life) | Self-report | 12 months | Not specified (psychiatric AEs) | No significant changes on BDI-II/POMS/SF-36 vs. controls; trend toward increased vitality | RCT; secondary analysis; adequate follow-up | https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-0052. |

| [13] | Lithuania | Controlled clinical trial | Overweight women; ~46 | Overweight/obesity; otherwise healthy | 48 h total water-only fast | Non-fasting/standard intake | Subjective stress ratings; mood scales; EEG; cognitive and psychomotor tests | Self-report (stress/mood); objective EEG | 48 h (acute) | Not specified | Moderate stress increase; no significant mood/cognition effects | Short-term clinical trial; small sample | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2017.10.028 |

| [21] | Italy | Randomized controlled pilot trial | Adults with MDD; n = 20 (pilot) | Major depressive disorder (outpatients) | Fasting-mimicking diet (FMD), three monthly 5-day cycles; adjunct to psychotherapy | Structured psychotherapy alone | Clinician- and self-rated depression severity; self-esteem; psychological QoL | Both (clinician-rated + self-report) | ~3 months | Not specified | Improved self-esteem and psychological QoL vs. psychotherapy; depressive-symptom reduction comparable | Pilot RCT; small sample | https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22971 |

| [3] | USA | Cross-sectional (Healthy Minds Study) | US college students; n > 8000 (2016–2020) | General college population | Self-reported fasting behavior (observational) | N/A (associational) | PHQ-9; GAD-7; SCOFF | Self-report | None (cross-sectional) | N/A (observational, no intervention) | Fasting behavior associated with higher odds of depression, anxiety, ED symptoms, SI, NSSI | Observational; residual confounding likely | https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1905136. |

| [22] | Morocco | Observational clinical report (letter) | Psychiatric outpatients with bipolar disorder | Bipolar disorder | Ramadan fasting (~29–30 days; dawn-to-sunset) | Non-fasting bipolar outpatients; adjusted for sleep, caffeine, lithium levels | Clinician-assessed relapse/recurrence | Clinician-rated | 1 month (Ramadan) | Relapse/recurrence events tracked (psychiatric) | Higher recurrence among fasters vs. non-fasters (adjusted) | Observational; brief report | https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20113 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bonaccorsi, V.; Romeo, V.M. Psychological and Psychiatric Consequences of Prolonged Fasting: Neurobiological, Clinical, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Nutrients 2026, 18, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010060

Bonaccorsi V, Romeo VM. Psychological and Psychiatric Consequences of Prolonged Fasting: Neurobiological, Clinical, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonaccorsi, Vincenzo, and Vincenzo Maria Romeo. 2026. "Psychological and Psychiatric Consequences of Prolonged Fasting: Neurobiological, Clinical, and Therapeutic Perspectives" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010060

APA StyleBonaccorsi, V., & Romeo, V. M. (2026). Psychological and Psychiatric Consequences of Prolonged Fasting: Neurobiological, Clinical, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Nutrients, 18(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010060