The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Nutrition Education on Pediatric Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Quality of the Studies

3.2. Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Liver Health and Metabolic and Anthropometric Outcomes in Pediatric MASLD

3.3. Dietary Composition of Mediterranean Diet Design for Pediatric Population with MASLD

3.4. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

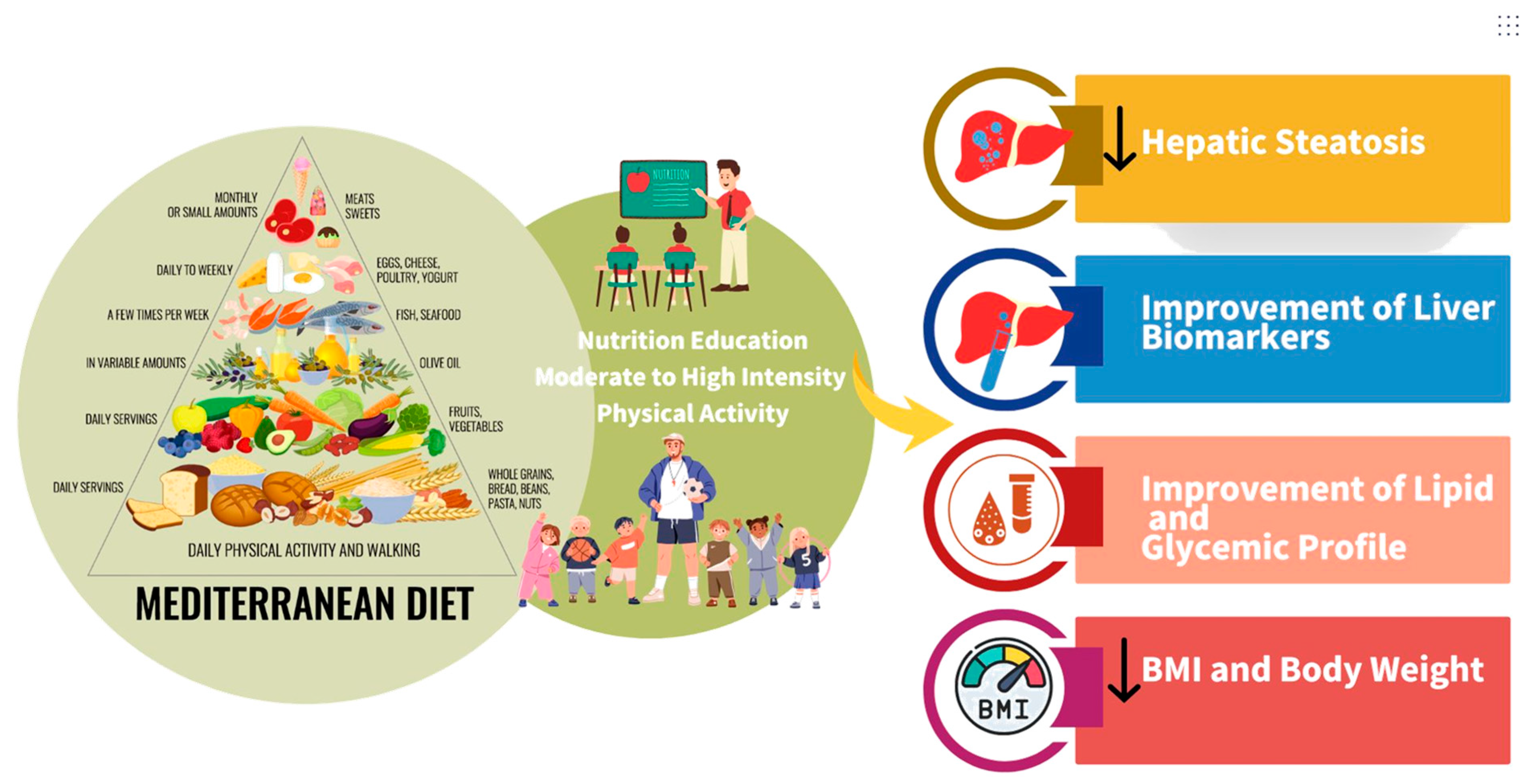

3.5. Mediterranean Diet Combined with Physical Activity and Nutrition Education Within the Intervention

4. Discussion

4.1. Mediterranean Diet and Pediatric MASLD

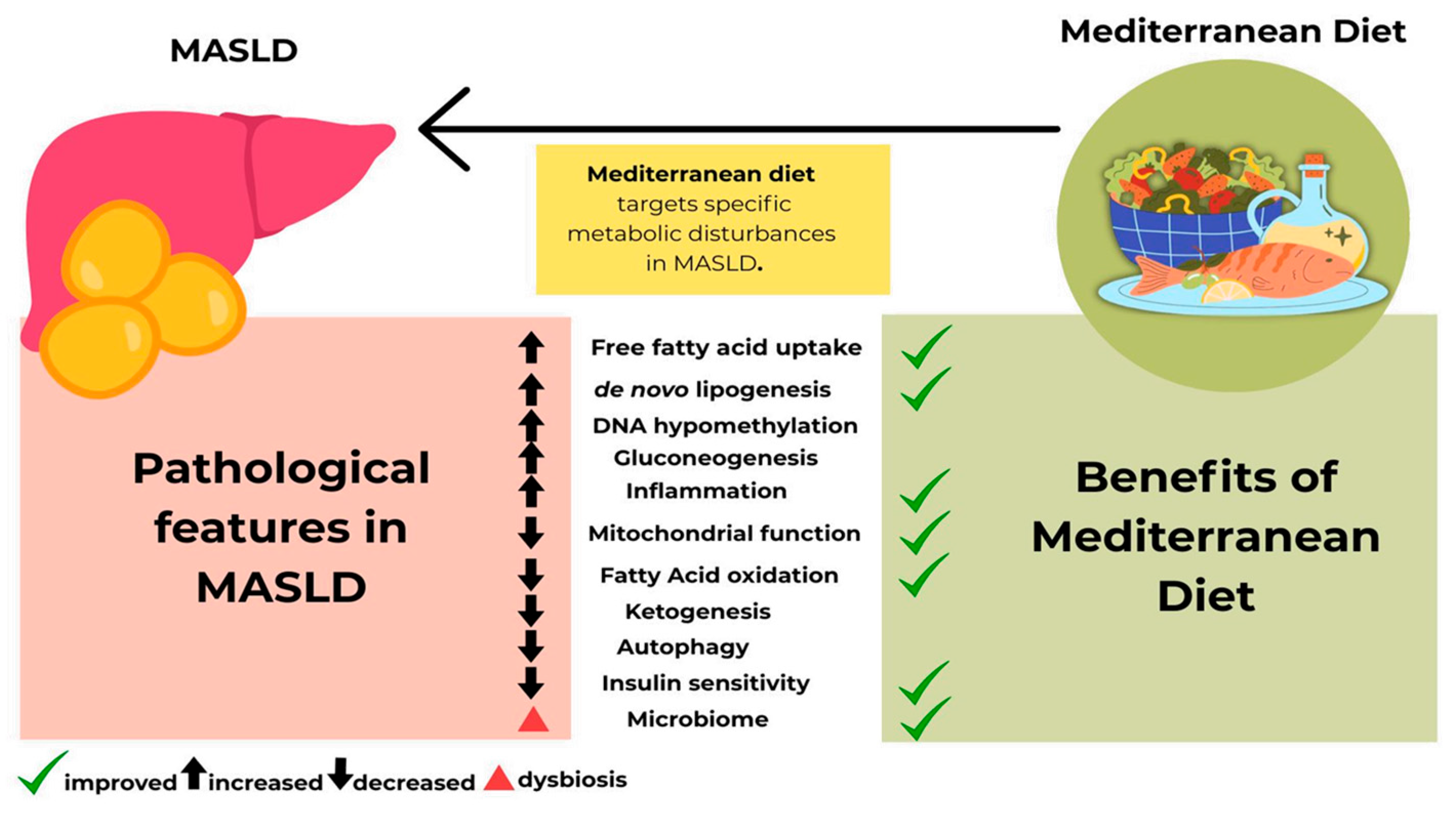

4.2. Biological Mechanism of Mediterranean Diet and Its Benefits for Pediatric MASLD

4.3. Energy and Macronutrient Distribution in Pediatric MASLD

4.4. Nutrition Education and Physical Activity and Their Benefits for Pediatric MASLD

4.5. Recommendations and Future Perspective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| ANDQCC | Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Quality Criteria Checklist |

| APRI | Aspartate Aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| CAP | Controlled Attenuation Parameter |

| CRP | C-reactive Protein |

| EVOO | Extra Virgin Olive Oil |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HIIT | High-Intensity Interval Training |

| HOMA/HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment/Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| KIDMED | Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for Children and Adolescents |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| MASLD | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MASH | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis |

| MD | Mediterranean Diet |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MNT | Medical Nutrition Therapy |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated Fatty Acid |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

| NASPGHAN | North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition |

| PNFI | Pediatric NAFLD Fibrosis Index |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| TAS | Total Antioxidant Status |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| WC | Waist Circumference |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WHR | Waist-to-Hip Ratio |

References

- Paik, J.M.; Kabbara, K.; Eberly, K.E.; Younossi, Y.; Henry, L.; Younossi, Z.M. Global burden of NAFLD and chronic liver disease among adolescents and young adults. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Díaz-Orozco, L.E.; Barranco-Fragoso, B.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. A Review of the Increasing Prevalence of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) in Children and Adolescents Worldwide and in Mexico and the Implications for Public Health. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e934134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Choi, M.; Ahn, S.B.; Yoo, J.-J.; Kang, S.H.; Cho, Y.; Song, D.S.; Koh, H.; Jeon, D.W.; Lee, H.W. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in pediatrics and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.L.; Schwimmer, J.B. Epidemiology of Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 17, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Kalligeros, M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 31, S32–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mu, C.; Li, K.; Luo, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Estimating Global Prevalence of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Overweight or Obese Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, H.; Wu, X.; Shi, T.; Chen, X.; Zhang, T. Increasing prevalence of NAFLD/NASH among children, adolescents and young adults from 1990 to 2017: A population-based observational study. Epidemiology 2021, 11, e042843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; El-Shabrawi, M.; Baur, L.A.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G.; Kehar, M.; Porta, G.; Lee, W.S.; Lefere, S.; Turan, S.; et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus on pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Med 2024, 5, 797–815.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, J.; Santos, S.; Geurtsen, M.L.; Felix, J.F.; Jaddoe, V.W.V. Risk factors and cardio-metabolic outcomes associated with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease in childhood. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 65, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzaki, M. Early burden, enduring risk: The alarming outcomes of pediatric MASLD. Hepatology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.-F.; Varady, K.A.; Wang, X.-D.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tayyem, R.; Latella, G.; Bergheim, I.; Valenzuela, R.; George, J.; et al. The role of dietary modification in the prevention and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international multidisciplinary expert consensus. Metab. -Clin. Exp. 2024, 161, 156028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-F.; Varady, K.A.; Wang, X.-D.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tayyem, R.; Latella, G.; Bergheim, I.; Valenzuela, R.; George, J.; et al. NASPGHAN Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthakos, S.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Adams, K.; Kohli, R.; Sathya, P.; Sundaram, S.; Vos, M.B.; Dhawan, A.; Caprio, S.; Behling, C.; et al. AASLD Practice Statement on the evaluation and management of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease in children. Hepatology 2025, 82, 1352–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sualeheen, A.; Tan, S.-Y.; Georgousopoulou, E.; Daly, R.M.; Tierney, A.C.; Roberts, S.K.; George, E.S. Mediterranean diet for the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in non-Mediterranean, Western countries: What’s known and what’s needed? Nutr. Bull. 2024, 49, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa025039 (accessed on 15 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Forouhi, N.G.; Khandelwal, S.; Prabhakaran, D.; Mozaffarian, D.; de Lorgeril, M. Definitions and potential health benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Views from experts around the world. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, V.; Bertozzi, B.; Fontana, L. Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Metabolic and Molecular Mechanisms. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Trenell, M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaró, C.M.; Bouzas, C.; Montemayor, S.; Casares, M.; Llompart, I.; Ugarriza, L.; Borràs, P.-A.; Martínez, J.A.; Tur, J.A. Effect of a Six-Month Lifestyle Intervention on the Physical Activity and Fitness Status of Adults with NAFLD and Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, F.M.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Malatino, L.; Musumeci, G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) prevention: Role of Mediterranean diet and physical activity. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2019, 8, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemayor, S.; Bouzas, C.; Mascaró, C.M.; Casares, M.; Llompart, I.; Abete, I.; Angullo-Martinez, E.; Zulet, M.Á.; Martínez, J.A.; Tur, J.A. Effect of Dietary and Lifestyle Interventions on the Amelioration of NAFLD in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: The FLIPAN Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metro, D.; Buda, M.; Manasseri, L.; Corallo, F.; Cardile, D.; Lo Buono, V.; Quartarone, A.; Bonanno, L. Role of Nutrition in the Etiopathogenesis and Prevention of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in a Group of Obese Adults. Med. Kaunas Lith. 2023, 59, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.M.; Bae, J.H.; Chang, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Moon, J.E.; Jeong, S.W.; Jang, J.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, H.S.; Yoo, J.-J.; et al. Effect of Nutrition Education in NAFLD Patients Undergoing Simultaneous Hyperlipidemia Pharmacotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handu, D.; Moloney, L.; Wolfram, T.; Ziegler, P.; Acosta, A.; Steiber, A. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Methodology for Conducting Systematic Reviews for the Evidence Analysis Library. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, V.; Marcellini, M.; Devito, R.; Ciampalini, P.; Piemonte, F.; Comparcola, D.; Sartorelli, M.R.; Angulo, P. NAFLD in children: A prospective clinical-pathological study and effect of lifestyle advice. Hepatology 2006, 44, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, L.; Arca, M.; Anania, C.; Cantisani, V.; Di Martino, M.; Chiesa, C. Arterial function and structure after a 1-year lifestyle intervention in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, U.E.; Isik, I.A.; Atalay, A.; Eraslan, A.; Durmus, E.; Turkmen, S.; Yurttas, A.S. The effect of a Mediterranean diet vs. a low-fat diet on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: A randomized trial. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, P.; Mania, A.; Mazur-Melewska, K.; Sluzewski, W.; Figlerowicz, M. A Decline in Aminotransferase Activity Due to Lifestyle Modification in Children with NAFLD. J. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 8, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtdaş, G.; Akbulut, G.; Baran, M.; Yılmaz, C. The effects of Mediterranean diet on hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation in adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Obes. 2022, 17, e12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.; Sood, V.; Lal, B.B.; Khanna, R.; Alam, S.; Sarin, S.K. Effect of Indo-Mediterranean diet versus calorie-restricted diet in children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A pilot randomized control trial. Pediatr. Obes. 2024, 19, e13163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, M.; Akbulut, U.E.; Okten, A. Association between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Presence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. Child. Obes. 2016, 12, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, C.; Mosca, A.; Vania, A.; Alterio, A.; Iasevoli, S.; Nobili, V. Good adherence to the Mediterranean diet reduces the risk for NASH and diabetes in pediatric patients with obesity: The results of an Italian Study. Nutrition 2017, 39–40, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimalesvaran, S.; Vajro, P.; Dhawan, A. Pediatric metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease: Current insights and future perspectives. Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abderbwih, E.; Mahanani, M.R.; Deckert, A.; Antia, K.; Agbaria, N.; Dambach, P.; Kohler, S.; Horstick, O.; Winkler, V.; Wendt, A.S. The Impact of School-Based Nutrition Interventions on Parents and Other Family Members: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom-Hoffman, J.; Wilcox, K.R.; Dunn, L.; Leff, S.S.; Power, T.J. Family Involvement in School-Based Health Promotion: Bringing Nutrition Information Home. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 37, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, R.; Davey, C.S.; Nanney, M.S. The Role of Family and Community Involvement in the Development and Implementation of School Nutrition and Physical Activity Policy. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, T.D.; Girz, L.; Stillar, A.; Tessier, C.; Lafrance, A. Parental Involvement and Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders: Perspectives from Residents in Psychiatry, Pediatrics, and Family Medicine. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crone, M.R.; Slagboom, M.N.; Overmars, A.; Starken, L.; van de Sande, M.C.E.; Wesdorp, N.; Reis, R. aThe Evaluation of a Family-Engagement Approach to Increase Physical Activity, Healthy Nutrition, and Well-Being in Children and Their Parents. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 747725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsembiante, L.; Targher, G.; Maffeis, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents: A role for nutrition? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Robles, M.A.; Ccami-Bernal, F.; Ortiz-Benique, Z.N.; Pinto-Ruiz, D.F.; Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Patiño, D.C. Adherence to Mediterranean diet associated with health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Dallolio, L.; Sanmarchi, F.; Lovecchio, F.; Falato, M.; Longobucco, Y.; Lanari, M.; Sacchetti, R. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Children and Adolescents and Association with Multiple Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; García-Hermoso, A.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Kales, S.N. Mediterranean Diet-Based Interventions to Improve Anthropometric and Obesity Indicators in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepper, C.; Crimmins, N.A.; Orkin, S.; Sun, Q.; Fei, L.; Xanthakos, S.; Mouzaki, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Young Children with Obesity. Child. Obes. 2023, 19, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, G.; Verde, L.; Zink, A.; Muscogiuri, G.; Albanesi, C.; Paganelli, A.; Barrea, L.; Scala, E. Plant-Based Foods for Chronic Skin Diseases: A Focus on the Mediterranean Diet. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, M.; Fresán, U. Do the Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet Increase with a Higher Proportion of Whole Plant-Based Foods? Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassale, C.; Fitó, M.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M.; Moya, A.; Gómez, S.F.; Schröder, H. Mediterranean diet and adiposity in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2022, 23, e13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Appel, L.J.; Creager, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Miller, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Robinson, J.G.; et al. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e1–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamley, S. The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Lopez-Moreno, J.; Gomez-Delgado, F.; Lopez-Miranda, J. Extra virgin olive oil: More than a healthy fat. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 72, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris-Etherton, M.; Yu-Poth, S.; Sabaté, J.; Ratcliffe, H.E.; Zhao, G.; Etherton, T.D. Nuts and their bioactive constituents: Effects on serum lipids and other factors that affect disease risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 504S–511S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Babio, N.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Ros, E.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Estruch, R.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Fiol, M.; et al. Dietary fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Y.N.; Amoon, A.T.; Su, B.; Velazquez-Cruz, R.; Ramírez-Palacios, P.; Salmerón, J.; Rivera-Paredez, B.; Sinsheimer, J.S.; Lusis, A.J.; Huertas-Vazquez, A.; et al. Serum lipids are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A pilot case-control study in Mexico. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour-Ghanaei, R.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F.; Naghipour, M.; Joukar, F. Biochemical markers and lipid profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients in the PERSIAN Guilan cohort study (PGCS), Iran. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, M.; Tiribelli, C.; Rosso, N. Exploring the Role of Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) in MASLD: Evidence from Human Consumption. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, V.; Parola, M.; Alisi, A.; Marra, F.; Piemonte, F.; Mombello, C.; Sutti, S.; Povero, D.; Maina, V.; Novo, E.; et al. Oxidative stress parameters in paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 26, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandato, C.; Lucariello, S.; Licenziati, M.R.; Franzese, A.; Spagnuolo, M.I.; Ficarella, R.; Pacilio, M.; Amitrano, M.; Capuano, G.; Meli, R.; et al. Metabolic, hormonal, oxidative, and inflammatory factors in pediatric obesity-related liver disease. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, G.; Giacco, A.; Scopigno, N.; Vigliotti, M.; Goglia, F.; Cioffi, F.; Silvestri, E. Mitochondria at the Crossroads: Linking the Mediterranean Diet to Metabolic Health and Non-Pharmacological Approaches to NAFLD. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Merino, J.; Sun, Q.; Fitó, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Dietary Polyphenols, Mediterranean Diet, Prediabetes, and Type 2 Diabetes: A Narrative Review of the Evidence. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 6723931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Pounis, G.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; Iacoviello, L.; de Gaetano, G. Mediterranean diet, dietary polyphenols and low grade inflammation: Results from the MOLI-SANI study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nani, A.; Murtaza, B.; Khan, A.S.; Khan, N.A.; Hichami, A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Polyphenols Contained in Mediterranean Diet in Obesity: Molecular Mechanisms. Molecules 2021, 26, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureda, A.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Julibert, A.; Bouzas, C.; Argelich, E.; Llompart, I.; Pons, A.; Tur, J.A. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Inflammatory Markers. Nutrients 2018, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Verduci, E.; Milanta, C.; Agostinelli, M.; Bona, F.; Croce, S.; Valsecchi, C.; Avanzini, M.A.; Zuccotti, G. The Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet on Inflamm-Aging in Childhood Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintó, X.; Fanlo-Maresma, M.; Corbella, E.; Corbella, X.; Mitjavila, M.T.; Moreno, J.J.; Casas, R.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Bulló, M.; et al. A Mediterranean Diet Rich in Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Is Associated with a Reduced Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Older Individuals at High Cardiovascular Risk. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1920–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Vitetta, L. Gut Microbiota Metabolites in NAFLD Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E.; Dudek, M. Knolle Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: The interplay between metabolism, microbes and immunity. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1596–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavandegar, A.; Heidarzadeh, A.; Angoorani, P.; Hasani-Ranjbar, S.; Ejtahed, H.-S.; Larijani, B.; Qorbani, M. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet can beneficially affect the gut microbiota composition: A systematic review. BMC Med. Genom. 2024, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidhuber, J.; Sur, P.; Fay, K.; Huntley, B.; Salama, J.; Lee, A.; Cornaby, L.; Horino, M.; Murray, C.; Afshin, A. The Global Nutrient Database: Availability of macronutrients and micronutrients in 195 countries from 1980 to 2013. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e353–e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarino, G.; Corsello, A.; Corsello, G. Macronutrient balance and micronutrient amounts through growth and development. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pixner, T.; Stummer, N.; Schneider, A.M.; Lukas, A.; Gramlinger, K.; Julian, V.; Thivel, D.; Mörwald, K.; Maruszczak, K.; Mangge, H.; et al. The Role of Macronutrients in the Pathogenesis, Prevention and Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in the Paediatric Population—A Review. Life 2022, 12, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, E.; Kokkinopoulou, A.; Pagkalos, I. Focus of Sustainable Healthy Diets Interventions in Primary School-Aged Children: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrafzadegan, N.; Rabiei, K.; Wong, F.; Roohafza, H.; Zarfeshani, S.; Noori, F.; Grainger-Gasser, A. The sustainability of interventions of a community-based trial on children and adolescents’ healthy lifestyle. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014, 10, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Samudyatha, U.C.; Muninarayana, C.; Vishwas, S.; Prasanna, K.B. Engaging school children in sustainable lifestyle: Opportunities and challenges. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.; Sousa, H.; Gouveia, É.R.; Lopes, H.; Peralta, M.; Martins, J.; Murawska-Ciałowicz, E.; Żurek, G.; Marques, A. School-Based Family-Oriented Health Interventions to Promote Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2023, 37, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormshak, E.A.; Fosco, G.M.; Dishion, T.J. Implementing Interventions with Families in Schools to Increase Youth School Engagement: The Family Check-Up Model. Sch. Ment. Health 2010, 2, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormshak, E.A.; Connell, A.; Dishion, T.J. An Adaptive Approach to Family-Centered Intervention in Schools: Linking Intervention Engagement to Academic Outcomes in Middle and High School. Prev. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Prev. Res. 2009, 10, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, M.; Sison, N.K.D.; Bruce, J.C.; Tiribelli, C.; Rosso, N. Understanding and Exploring the Food Preferences of Filipino School-Aged Children Through Free Drawing as a Projective Technique. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B.W.; Ziegler, J.; Parrott, J.S.; Handu, D. Pediatric Weight Management Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines: Components and Contexts of Interventions. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1301–1311.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, D.M.; Brann, L.S.; O’Brien, S.; Handu, D.; Rozga, M. Prevention of Pediatric Overweight and Obesity: Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Based on an Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 410–423.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.C.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Thodis, T.; Ward, G.; Trost, N.; Hofferberth, S.; O’Dea, K.; Desmond, P.V.; Johnson, N.A.; Wilson, A.M. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year of Publication | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nobili et al., 2006 [27] | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Pacifico et al., 2013 [28] | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Akbulut et al., 2022 [29] | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Malecki et al., 2021 [30] | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Yurtdaş et al., 2022 [31] | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Deshmukh et al., 2024 [32] | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Cakir et al., 2016 [33] | + | + | + | § | § | § | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Della Corte 2017 [34] | + | + | + | § | § | § | + | + | + | + | Positive |

| Study (Author, Year, and Country) | Type and Duration of Study | Participant Characteristics on MD Arm; MASLD Diagnosis | Intervention/ Grouping and Comparator/Control | Effects of Mediterranean Diet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Steatosis, Fibrosis, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress | Liver Parameters | Blood Lipid and Blood Sugar Profile | Anthropometric and Clinical Measurements | ||||

| Deshmukh et al., 2024 [32]; India | Randomized control trial; 180 days | 19 children and adolescents with MASLD; male/female; 8–18 years old; age-specific BMI > 85th percentile overweight and obese; liver biopsy | Mediterranean diet vs. calorie-restricted diet | ↓ Hepatic steatosis determined by CAP values ↓ Liver stiffness measurement ↓ PNFI ↔ TNF-a ↔ IL-6 | ↓ AST ↓ ALT | ↓ TC ↓ LDL ↓ HOMA-IR | ↓ Body weight ↓ BMI ↓ Triceps skinfold thickness ↓ WC |

| Yurtdaş et al., 2022 [31]; Turkey | Randomized control trial; 12 weeks | 22 adolescents with MASLD and obesity; 11–18 years old; age-specific BMI ≥ 95th percentile; liver ultrasound | Mediterranean diet vs. low-fat diet | ↓ Hepatic steatosis 13.6% of the adolescents did not have fatty liver ↑ TAS, ↑ PON-1 ↑ GSH-Px ↑ Glutathione ↓ Malondialdehyde ↓ TNF-a, ↓ IL-6 ↓ IL-8, ↓ IL-1β ↑ IL-10, ↓ CRP levels | ↓ AST ↓ ALT ↓ GGT | ↔ TG ↔ TC ↔ LDL ↔ HDL ↓ Insulin ↓ HOMA-IR | ↓ Body weight ↓ BMI ↓ WC ↔ Fat-free mass ↓ Waist–hip ratio ↓ Body fat |

| Akbulut et al., 2022 [29]; Turkey | Randomized control trial; 12 weeks | 30 children and adolescents with MASLD; male/female; 9–17 years old; age-specific BMI > 85 percentile overweight and obese; liver ultrasound | Mediterranean diet vs. low-fat diet | ↓ Hepatic steatosis ↓ Liver stiffness | ↓ AST ↓ ALT | ↓ HOMA-IR ↓ TC ↓ TG | ↓ Body weight ↓ BMI ↓ Body fat ratio |

| Malecki et al. 2021 [30]; Poland | Prospective consecutive study | 49 children and adolescents with MASLD; male/female; 3–16 years old; BMI are normal, overweight, and obese; liver ultrasound | Mediterranean diet; compliant vs. non-compliant | ↓ APRI (AST to PLT ratio) for patients who 100% followed the lifestyle modification | ↓ AST ↓ GGT for patients who 100% followed the lifestyle modification | ↓ BMI for patients who 100% followed the lifestyle modification | |

| Pacifico et al., 2013 [28]; Italy | Prospective interventional cohort study; 1 year | 120 children and adolescents with MASLD; male/female; 9–17 years old; age-specific BMI > 95 percentile obese; liver ultrasound and MRI | Mediterranean diet; before and after intervention | ↓ Hepatic fat fraction ↓ High-sensitivity C-reactive protein | ↓ AST ↓ ALT ↔ GGT | ↓ TG ↔ TC ↔ LDL ↔ HDL ↔ non-HDL ↓ HOMA-IR ↔ Fasting Glucose | ↓ BMI ↓ WC ↓ Fat mass ↓ Diastolic blood pressure |

| Nobili et al., 2006 [27]; Italy | Prospective observational study with an interventional component | 57 children and adolescents with MASLD; male/female; 3–17 years old; age-specific BMI range of 15.2 to 38.4, mean BMI of 26.3; liver ultrasound and MRI | Low-calorie–Mediterranean diet | ↓ Hepatic steatosis/↓ echogenicity, reflecting an improvement (reduction) in hepatic fat accumulation | ↓ AST ↓ ALT ↔ GGT | ↓ TC ↓ TG ↓ Fasting Glucose ↓ Fasting Insulin ↓ HOMA | ↓ BMI ↓ Weight |

| Cakir et al., 2016 [33]; Turkey | Cross-sectional-association | 106 children and adolescents, obese with NAFLD; male/female; average BMI of 30.6; average age of 12 years old; liver ultrasound | Mediterranean diet; adherence comparison between obese children with and without NAFLD and healthy children | No significant difference was found in KIDMED index score between NAFLD patients with grade 1, 2, or 3 hepatic steatosis | No significant correlation was found with ALT | No significant correlation was found with TG, TC, or HOMA-IR | KIDMED index score was negatively correlated with BMI. No significant correlation was found with body fat. |

| Della Corte et al., 2017 [34]; Italy | Cross-sectional-association | 243 children, with 166 patients with fatty liver and 77 without fatty liver; 53 cases of NASH; all were obese/overweight (BMI 28.16 kg/m2); ages 10–17 years old); liver ultrasound and liver biopsy | Mediterranean diet; adherence comparison between with fatty liver, without fatty liver, and with NASH | ↓ Risk of NASH, less hepatic inflammation, and lower NAFLD activity score (NAS) on high adherence to MD ↓ CRP level on high adherence to MD ↑ KIDMED score is independently associated with lower risk of liver fibrosis in children with NAFLD. | ↓ ALT and AST levels in the high MD adherence group | Improved insulin sensitivity ↓ HOMA-IR ↓ fasting glucose ↓ TG | No differences were found for anthropometric parameters (BMI, weight, and waist circumference) between these groups. Negative correlation between the lower values of KIDMED score and blood pressure was observed. |

| Study (Author, Year, and Country) | Macronutrient Distribution (% of Total Energy) and Additional Dietary Recommendations | Focused on Nutrition Education/Counseling | Physical Activity Recommended During the Study | Summary of Effects on Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deshmukh et al., 2024 [32] (India) RCT; 180 days | Calorie Intake: Age- and gender-appropriate energy requirements per day Carbohydrates: 40–45% Fat: 30–35% (<10% saturated fat) Protein: 20% Colorful veggies, fish/less red meat, legumes, multi-grain atta, nuts, olive oil/mustard oil; cinnamon, garlic, pepper added | Dietary principles include restricting saturated fat intake and avoiding processed/packaged products, alcohol, instant beverages, carbonated/sugary drinks, candy, ice cream, cream biscuits, cake, noodles, and sweets high in sugar and fat. | High intensity minimum of 3 sets/day for 5 times per week, along with walking/jogging/cycling for at least 30 min to 1 h. | Hepatic and Fibrosis: ↓ hepatic steatosis (CAP), ↓ liver stiffness, ↓ pediatric NAFLD fibrosis index; Inflammation: No significant change in TNF-α, IL-6; Liver Enzymes: ↓ AST, ALT; Lipids and Glucose: ↓ TC, LDL, HOMA-IR; Anthropometrics: ↓ body weight, BMI, triceps skinfold, WC |

| Yurtdaş et al., 2022 [31] (Turkey) RCT; 12 weeks | Calorie Intake: BMI-based energy requirements per day with a low physical activity factor Carbohydrates: 40% Fat: 35–40% (<10% saturated fat) Protein: 20% Fish, legumes 2–3 times/week; walnuts 20 g/day; olive oil 30–45 g/day daily; restrict saturated fats and processed foods | Dietary principles include restricting saturated fat intake and avoiding processed/packaged products, alcohol, instant beverages, carbonated/sugary drinks, candy, ice cream, cream biscuits, cake, noodles, and sweets high in sugar and fat. | Usual level of physical activity | Hepatic and Fibrosis: ↓ hepatic steatosis (13.6% no fatty liver at follow-up); Oxidative Stress: ↑ TAS, PON-1, GSH-Px, glutathione; ↓ malondialdehyde; Inflammation: ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β; ↑ IL-10; ↓ CRP; Liver Enzymes: ↓ AST, ALT, GGT; Lipids and Glucose: no significant change in TG, TC, LDL, HDL; ↓ insulin, HOMA-IR; Anthropometrics: ↓ body weight, BMI, WC, WHR, body fat |

| Akbulut et al., 2022 [29] (Turkey) RCT; 12 weeks | Calorie Intake: Age- and gender-appropriate energy requirement per day using Schofield equation for energy expenditure Carbohydrates: 40–44% Fat: 35–40% (<10% saturated fat) Protein: 20% Rich in plant-based foods, extra virgin olive oil as main added fat | During the education session, children received nutritional recommendations and a food-group list specifying preferred choices and approximate serving numbers and sizes per day, based on dietary modeling. Foods to be avoided were identified, and potential alternatives with equivalent caloric values were provided. Patients were instructed not to consume any foods outside the recommended list. | Twelve-week exercise program for 30–45 min/3 days in the first two weeks and for 60 min/4–5 days in the following weeks. | Hepatic and Fibrosis: ↓ hepatic steatosis, liver stiffness. Liver enzymes: ↓ AST, ALT; Lipids and Glucose: ↓ HOMA-IR, TC, TG; Anthropometrics: ↓ body weight, BMI, body fat ratio |

| Pacifico et al., 2013 [28] (Italy) Prospective interventional. 1 year | Calorie Intake: Hypocaloric: 25–30 kcal/kg/day Carbohydrates: 50–60% Fat: 23–30% (two-thirds unsaturated, one-third saturated) Protein: 15–20% Emphasis on unrefined carbs, fiber (whole grains, vegetables, fruits), low-fat dairy; omega-6–omega-3 ratio approx. 4:1 | Guidance on healthy eating for child and family. | Moderate daily exercise program (60 min/day at least 5 days a week). | Hepatic and Fibrosis: ↓ hepatic fat fraction, ↓ hs-CRP; Liver enzymes: ↓ AST, ALT, no change GGT; Lipids & Glucose: ↓ TG, HOMA-IR, no significant change in TC, LDL, HDL, fasting glucose; Anthropometrics: ↓ BMI, WC, fat mass, diastolic BP |

| Nobili et al., 2006 [27] (Italy) Prospective observational; interventional | Calorie Intake: Balanced low-calorie: 25–30 kcal/kg/day Carbohydrates: 50–60% Fat: 23–30% (two-thirds unsaturated, one-third saturated) Protein: 15–20% Balanced diet tailored individually; omega-6–omega-3 ratio approx. 4:1; goal of negative calorie balance | Guidance on healthy eating for child and family. | Aerobic exercise (30–45 min/d at least 3 times a week) | Hepatic and Fibrosis: ↓ hepatic steatosis; Liver enzymes: ↓ AST, ALT, no change GGT; Lipids and Glucose: ↓ TC, TG, fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA; Anthropometrics: ↓ BMI, weight |

| Macronutrient | WHO Recommendation [71] | MASLD Studies (Practical Targets) [27,28,29,31,32] |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | 45–60% of total energy Free sugars < 10% (ideally < 5%) Mostly from whole grains, fruits, vegetables, pulses | Approximately 40–45% of total energy, prioritizing complex carbs (whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits) |

| Fat | ≤30% of total energy Saturated fat < 10% | Approximately 30–40% of total energy, emphasizing unsaturated fats (EVOO, nuts) Saturated fat < 10% |

| Protein | 0.8–0.9 g/kg/day (≈10–15% of energy) | Approximately 20% of total energy, mainly from fish, legumes, dairy; limited red/processed meats |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bernardino, M.; Tiribelli, C.; Rosso, N. The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Nutrition Education on Pediatric Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Review. Nutrients 2026, 18, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010028

Bernardino M, Tiribelli C, Rosso N. The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Nutrition Education on Pediatric Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Review. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernardino, Melvin, Claudio Tiribelli, and Natalia Rosso. 2026. "The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Nutrition Education on Pediatric Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Review" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010028

APA StyleBernardino, M., Tiribelli, C., & Rosso, N. (2026). The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Nutrition Education on Pediatric Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Review. Nutrients, 18(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010028