A Narrative Review: A1 and A2 Milk Beta Caseins on Gut Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

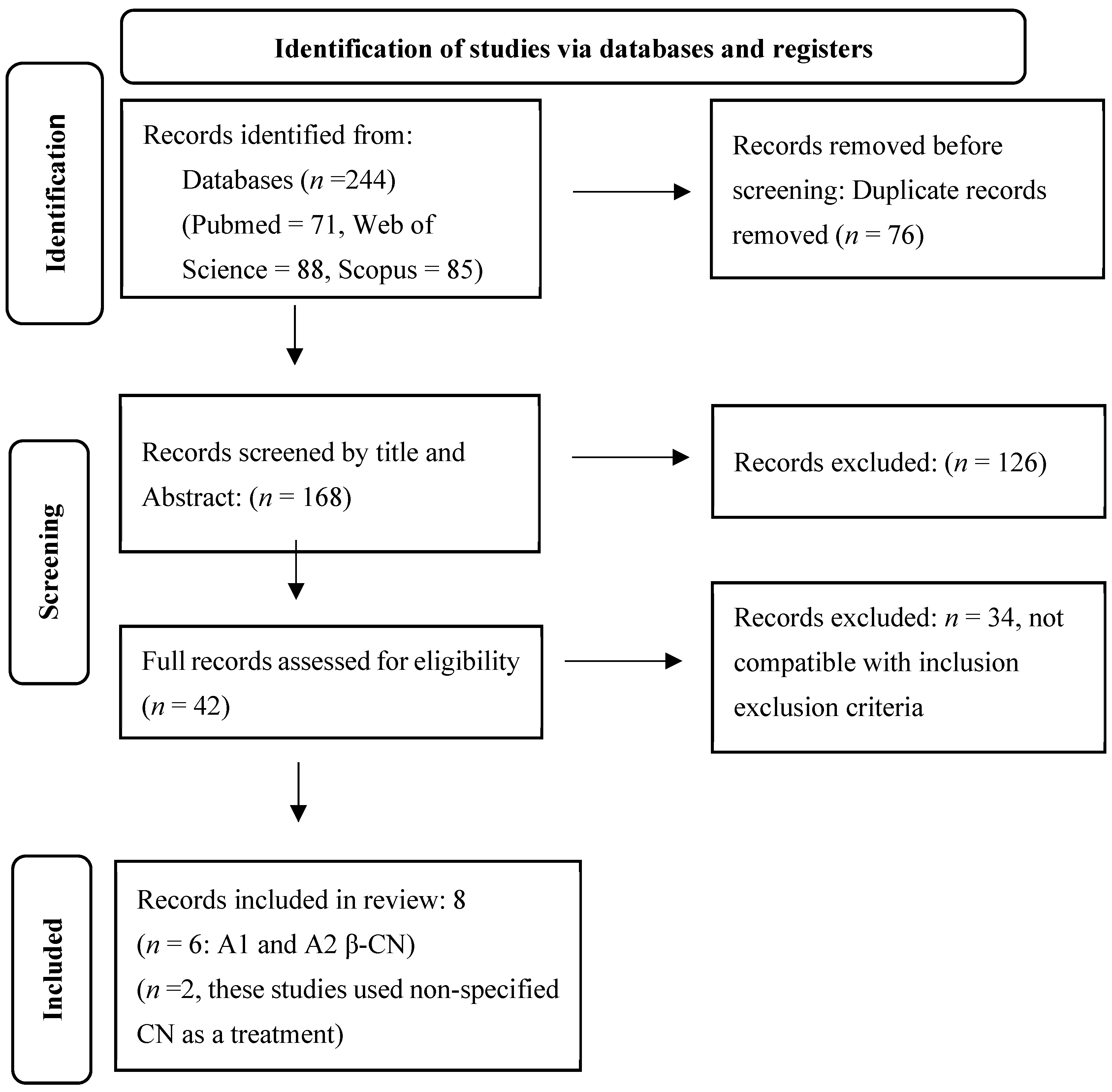

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. A1 and A2 β-CN and Gut Microbiota

3.2.1. Phylum Level

3.2.2. Family Level

3.2.3. Genus Level

3.2.4. Species Level

3.2.5. Short Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Profile and Gut Microbiota

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaucheron, F. Milk and dairy products: A unique micronutrient combination. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2011, 30, 400S–409S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.W.; Haenlein, G.F. Milk and Dairy Products in Human Nutrition: Production, Composition and Health; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Savaiano, D.A.; Ritter, A.J.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; James, G.M.; Longcore, A.T.; Chandler, J.R.; Walker, W.A.; Foyt, H.L. Improving lactose digestion and symptoms of lactose intolerance with a novel galacto-oligosaccharide (RP-G28): A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szilagyi, A.; Ishayek, N. Lactose intolerance, dairy avoidance, and treatment options. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, F.J.; Brannon, P.M.; Carpenter, T.O.; Fernandez, J.R.; Gilsanz, V.; Gould, J.B.; Hall, K.; Hui, S.L.; Lupton, J.; Mennella, J. NIH consensus development conference statement: Lactose intolerance and health. NIH Consens. State Sci. Statements 2010, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.; Woodford, K.; Kukuljan, S.; Pal, S. Comparative effects of A1 versus A2 beta-casein on gastrointestinal measures: A blinded randomised cross-over pilot study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, M.; Savaiano, D.A. Two-week consumption of a2 milk produces significantly lower fecal urgency as compared to milk containing both a1 and a2 β-casein: A double-blinded, randomized, cross-over trial. Investig. Eff. Beta-Casein Protein Var. Lact. Maldigestion 2023, 77, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Auestad, N.; Layman, D.K. Dairy bioactive proteins and peptides: A narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedorowicz, E.; Rozmus, D.; Sienkiewicz-Szłapka, E.; Jarmołowska, B.; Kami nski, S. Does a little difference make a big difference? Bovine β-Casein A1 and A2 variants and human health—An update. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2022, 23, 15637. [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Kwai-Hang, K.; Grosclaude, F. Genetic polymorphism of milk proteins. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry—1 Proteins: Part A/Part B; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 739–816. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, A.; Dunner, S.; Canon, J. use of PCR-single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis for detection of bovine β-casein variants A1, A2, A3, and B. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 77, 2629–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massella, E.; Piva, S.; Giacometti, F.; Liuzzo, G.; Zambrini, A.V.; Serraino, A. Evaluation of bovine beta casein polymorphism in two dairy farms located in northern Italy. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2017, 6, 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, C.; Arcangeli, C.; Ciullo, M.; Torricelli, M.; Cinti, G.; Fisichella, S.; Biagetti, M. Frequencies evaluation of β-casein gene polymorphisms in dairy cows reared in central Italy. Animals 2020, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorkhali, A.; Sherpa, C.; Koirala, P.; Sapkota, S.; Pokharel, B. The global scenario of A1, A2 β-Casein variant in cattle and its impact on human health. Glob. J. Agric. Allied Sci. 2021, 3, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; De, S.; Dewangan, R.; Tamboli, R.; Gupta, R. Potential status of A1 and A2 variants of bovine beta-casein gene in milk samples of Indian cattle breeds. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 4878–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, S.; Cieślińska, A.; Kostyra, E. Polymorphism of bovine beta-casein and its potential effect on human health. J. Appl. Genet. 2007, 48, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qiao, W.C.; Zhang, M.H.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhao, J.Y.; Chen, L.J. Bovine milk with variant β-casein types on immunological mediated intestinal changes and gut health of mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 970685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, X.R.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.J.; Yang, X.Y.; Man, C.X. The Immunomodulatory Effects of A2 β-Casein on Immunosuppressed Mice by Regulating Immune Responses and the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 16, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.R.U.; Kapila, R.; Sharma, R.; Saliganti, V.; Kapila, S. Comparative evaluation of cow β-casein variants (A1/A2) consumption on Th 2-mediated inflammatory response in mouse gut. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.P.; McNabb, W.C.; Roy, N.C.; Woodford, K.B.; Clarke, A.J. Dietary A1 β-casein affects gastrointestinal transit time, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 activity, and inflammatory status relative to A2 β-casein in Wistar rats. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, K. A1 Beta-Casein, Type 1 Diabetes and Links to Other Modern Illnesses; Lincoln University: Lincoln, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuffa, S.; Walton, G.; Fagbodun, E.; Kitchen, I.; Swann, J.; Bailey, A. Casein Intake Post Weaning Modulates Gut Microbial, Metabolic and Behavioral Profiles in Rats. iScience 2021, 24, 103048. [Google Scholar]

- Nuomin; Baek, R.; Tsuruta, T.; Nishino, N. Modulatory Effects of A1 Milk, A2 Milk, Soy, and Egg Proteins on Gut Microbiota and Fermentation. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guantario, B.; Giribaldi, M.; Devirgiliis, C.; Finamore, A.; Colombino, E.; Capucchio, M.T.; Evangelista, R.; Motta, V.; Zinno, P.; Cirrincione, S.; et al. A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Impact of Bovine Milk Containing Different Beta-Casein Profiles on Gut Health of Ageing Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.S.J.; McRae, J.L.; Enjapoori, A.K.; Lefèvre, C.M.; Kukuljan, S.; Dwyer, K.M. Dietary Cows’ Milk Protein A1 Beta-Casein Increases the Incidence of T1D in NOD Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.-H.; Kim, N.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.S.; Park, M.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, D.H. Beneficial effect of consuming milk containing only A2 beta-casein on gut microbiota: A single-center, randomized, double-blind, cross-over study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Wu, X.M.; Zhao, J.H.; Ma, X.T.; Murad, M.S.; Mu, G.Q. Peptidome comparison on the immune regulation effects of different casein fractions in a cyclophosphamide mouse model. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Feng, J.H.; Han, H.Y.; Huang, J.L.; Zhang, L.A.; Hettinga, K.; Zhou, P. Anti-inflammatory effects of dietary β-Casein peptides and its peptide QEPVL in a DSS-induced inflammatory bowel disease mouse model. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ju, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Aluko, R.E.; He, R. Rice bran attenuated obesity via alleviating dyslipidemia, browning of white adipocytes and modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 2406–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, A.; Marchesi, N.; Govoni, S.; Coppola, A.; Gazzaruso, C. The role of gut microbiota in obesity, diabetes mellitus, and effect of metformin: New insights into old diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2019, 49, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A.; Skov, T.H.; Bahl, M.I.; Roager, H.M.; Christensen, L.B.; Ejlerskov, K.T.; Mølgaard, C.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Licht, T.R. Establishment of intestinal microbiota during early life: A longitudinal, explorative study of a large cohort of Danish infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2889–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgo, F.; Verduci, E.; Riva, A.; Lassandro, C.; Riva, E.; Morace, G.; Borghi, E. Relative abundance in bacterial and fungal gut microbes in obese children: A case control study. Child. Obes. 2017, 13, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indiani, C.M.d.S.P.; Rizzardi, K.F.; Castelo, P.M.; Ferraz, L.F.C.; Darrieux, M.; Parisotto, T.M. Childhood obesity and firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio in the gut microbiota: A systematic review. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, C.C.; Monteil, M.A.; Davis, E.M. Overweight and obesity in children are associated with an abundance of Firmicutes and reduction of Bifidobacterium in their gastrointestinal microbiota. Child. Obes. 2020, 16, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Gil-Campos, M.; Gil, A. Mechanisms of action of probiotics. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.M.; De Souza, R.; Kendall, C.W.; Emam, A.; Jenkins, D.J. Colonic health: Fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joossens, M.; Huys, G.; Cnockaert, M.; De Preter, V.; Verbeke, K.; Rutgeerts, P.; Vandamme, P.; Vermeire, S. Dysbiosis of the faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn’s disease and their unaffected relatives. Gut 2011, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, X.C.; Tickle, T.L.; Sokol, H.; Gevers, D.; Devaney, K.L.; Ward, D.V.; Reyes, J.A.; Shah, S.A.; LeLeiko, N.; Snapper, S.B. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Ridlon, J.M.; Hylemon, P.B.; Thacker, L.R.; Heuman, D.M.; Smith, S.; Sikaroodi, M.; Gillevet, P.M. Linkage of gut microbiome with cognition in hepatic encephalopathy. Am. J. Physiol. -Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 302, G168–G175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antharam, V.C.; Li, E.C.; Ishmael, A.; Sharma, A.; Mai, V.; Rand, K.H.; Wang, G.P. Intestinal dysbiosis and depletion of butyrogenic bacteria in Clostridium difficile infection and nosocomial diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2884–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, A.P.; Al Zaidan, S.; Bangarusamy, D.K.; Al-Shamari, S.; Elhag, W.; Terranegra, A. Increased relative abundance of ruminoccocus is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk in an obese population. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 849005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Yang, F.; Cao, J.; Ding, W.; Yan, S.; Shi, W.; Wen, S.; Yao, L. Alterations of gut microbiota and metabolome with Parkinson’s disease. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 160, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, F.S.; Naseri, K.; Hu, H. Gut microbiota composition in patients with neurodegenerative disorders (Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s) and healthy controls: A systematic review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avire, N.J.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K. A review of Streptococcus pyogenes: Public health risk factors, prevention and control. Pathogens 2021, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Wilson, M.E.; Wertheim, H.F.; Nghia, H.D.T.; Taylor, W.; Schultsz, C. Streptococcus suis: An emerging human pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wei, Y.; Pi, C.; Zheng, W.; Zuo, Y.; Shi, P.; Chen, J.; Xiong, L.; Chen, T.; Liu, H. The therapeutic value of bifidobacteria in cardiovascular disease. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Cantabrana, C.; Delgado, S.; Ruiz, L.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Sánchez, B.; Margolles, A. Bifidobacteria and their health-promoting effects. In Bugs as Drugs: Therapeutic Microbes for the Prevention and Treatment of Disease; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Collins, M.K.; Moloney, G.M.; Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Fülling, C.; Morley, S.J.; Clarke, G.; Schellekens, H.; Cryan, J.F. Short chain fatty acids: Microbial metabolites for gut-brain axis signalling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 546, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 508738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Zhou, D.-D.; Wu, S.-X.; Huang, S.-Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.-J.; Shang, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Health benefits and side effects of short-chain fatty acids. Foods 2022, 11, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Li, M.; Qian, M.; Yang, Z.; Han, X. Co-cultures of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus subtilis enhance mucosal barrier by modulating gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Wang, S.; Ahmadi, S.; Hayes, J.; Gagliano, J.; Subashchandrabose, S.; Kitzman, D.W.; Becton, T.; Read, R.; Yadav, H. Human-origin probiotic cocktail increases short-chain fatty acid production via modulation of mice and human gut microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianqin, S.; Leiming, X.; Lu, X.; Yelland, G.W.; Ni, J.; Clarke, A.J. Effects of milk containing only A2 beta casein versus milk containing both A1 and A2 beta casein proteins on gastrointestinal physiology, symptoms of discomfort, and cognitive behavior of people with self-reported intolerance to traditional cows’ milk. Nutr. J. 2015, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Li, Z.; Ni, J.; Yelland, G. Effects of conventional milk versus milk containing only A2 β-casein on digestion in Chinese children: A randomized study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 69, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Du, Y.; Chi, Z.; Bian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Teng, T.; Shi, B. Isobutyrate confers resistance to inflammatory bowel disease through host–microbiota interactions in pigs. Research 2025, 8, 0673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Hou, J.; Cao, Y.; Wei, H.; Sun, K.; Ji, X.; Chu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Shi, L. Dietary isobutyric acid supplementation improves intestinal mucosal barrier function and meat quality by regulating cecal microbiota and serum metabolites in weaned piglets. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1565216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Nurgali, K.; Kumar Mishra, V. Food proteins as source of opioid peptides—A review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E.; Eker, F.; Yılmaz, S.; Karav, S.; Oz, E.; Brennan, C.; Proestos, C.; Zeng, M.; Oz, F. BCM-7: Opioid-like peptide with potential role in disease mechanisms. Molecules 2024, 29, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, S.; Trompette, A.; Claustre, J.; Homsi, M.E.; Garzón, J.; Jourdan, G.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; Plaisancié, P. β-Casomorphin-7 regulates the secretion and expression of gastrointestinal mucins through a μ-opioid pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, G1105–G1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulipano, G. Role of bioactive peptide sequences in the potential impact of dairy protein intake on metabolic health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Harris, D.; Hill, J.; Bibby, N.; Wasmuth, H. Type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and cow milk: Casein variant consumption. Diabetologia 1999, 42, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugesen, M.; Elliott, R. Ischaemic heart disease, type 1 diabetes, and cow milk A1 beta-casein. N. Z. Med. J. 2003, 116, U295. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Subjects | CN Interventions | Days of CN Intervention | Sequencing Method | Distinctive Changes in Gut Microbiota | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 β-CN | A2 β-CN | |||||

| [25] | Balb-C Mice | Control A2A2 A1A2 | 28 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 hypervariable region | Ruminococcaceae | Deferribacteraceae, Desulfovibrionaceae |

| [26] | NOD/ShiLtJArc mice | A1 A2 | 210 | Metagenome shotgun pyrosequencing (paired end with read length of 101 nucleotides) | Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus suis | Not reported |

| [17] | Pathogen-free Balb/c mice | Control A1 A2 | 28 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 region | Not reported | Ruminococcaceae, Lactobacillus animalis |

| [24] | C57BL/6 mice | Mixed CN A1 A2 Soy Egg white | 28 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V4 region | Desulfobacterota, Muribaculaceae, Staphylococcaceae | Eggerthellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Enterococcaceae |

| [18] | Pathogen-free Balb/c mice | Normal Model Low A2 Medium A2 High A2 High beta | 35 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 region | Streptococcus, Prevotella, Thermoactinomyces, Anaerotruncus, Ethanoligenens | Lactobacillus, Weissella, Ruminococcus, and Bifidobacterium |

| [27] | Humans | A1 milk A2 milk | 35 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 region | No changes in alpha diversity Significantly decreased Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes Significantly increased Actinobacteria | No changes in alpha diversity Significant shift in beta diversity between before and after A2 consumption Enrichment of classes Actinobacteria, Coriobacteria and family Lachnospiraceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, and Coriobacteriaceae and genus Bifidobacterium and Blautia, and species Bifidobacterium longum and Blautia wexlerae |

| * [28] | BALB/C mice | Control Model Kappa CN (KCN) β-CN βK-CN CN micells | 28 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 region | Increased Muribaculaceae_norank, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Lachnospiraceae_uncultured, Alistipes, Odoribacter, Blautia, and Clostridia UCG-014_norank Reduced Prevotellaceae | |

| * [29] | C57BL/6J male mice | Control Model Positive control β-CN group Bioactive peptide group | 7 | 16S rRNA sequencing targeting V3–V4 region | Greater Shanno index and lower Simpson index Increased Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Candidatus_Saccharibacte Highest level of Escherichia Increased Enterobacteriaceae and Erysipelotrichaceae at family level | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sujani, S.; Czerwinski, K.J.; Savaiano, D.A. A Narrative Review: A1 and A2 Milk Beta Caseins on Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2026, 18, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010138

Sujani S, Czerwinski KJ, Savaiano DA. A Narrative Review: A1 and A2 Milk Beta Caseins on Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010138

Chicago/Turabian StyleSujani, Sathya, Klaudia J. Czerwinski, and Dennis A. Savaiano. 2026. "A Narrative Review: A1 and A2 Milk Beta Caseins on Gut Microbiota" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010138

APA StyleSujani, S., Czerwinski, K. J., & Savaiano, D. A. (2026). A Narrative Review: A1 and A2 Milk Beta Caseins on Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 18(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010138