Vitamin C and Benzoic Acid Intake in Patients with Kidney Disease: Is There Risk of Benzene Exposure?

Abstract

1. Introduction and Methods

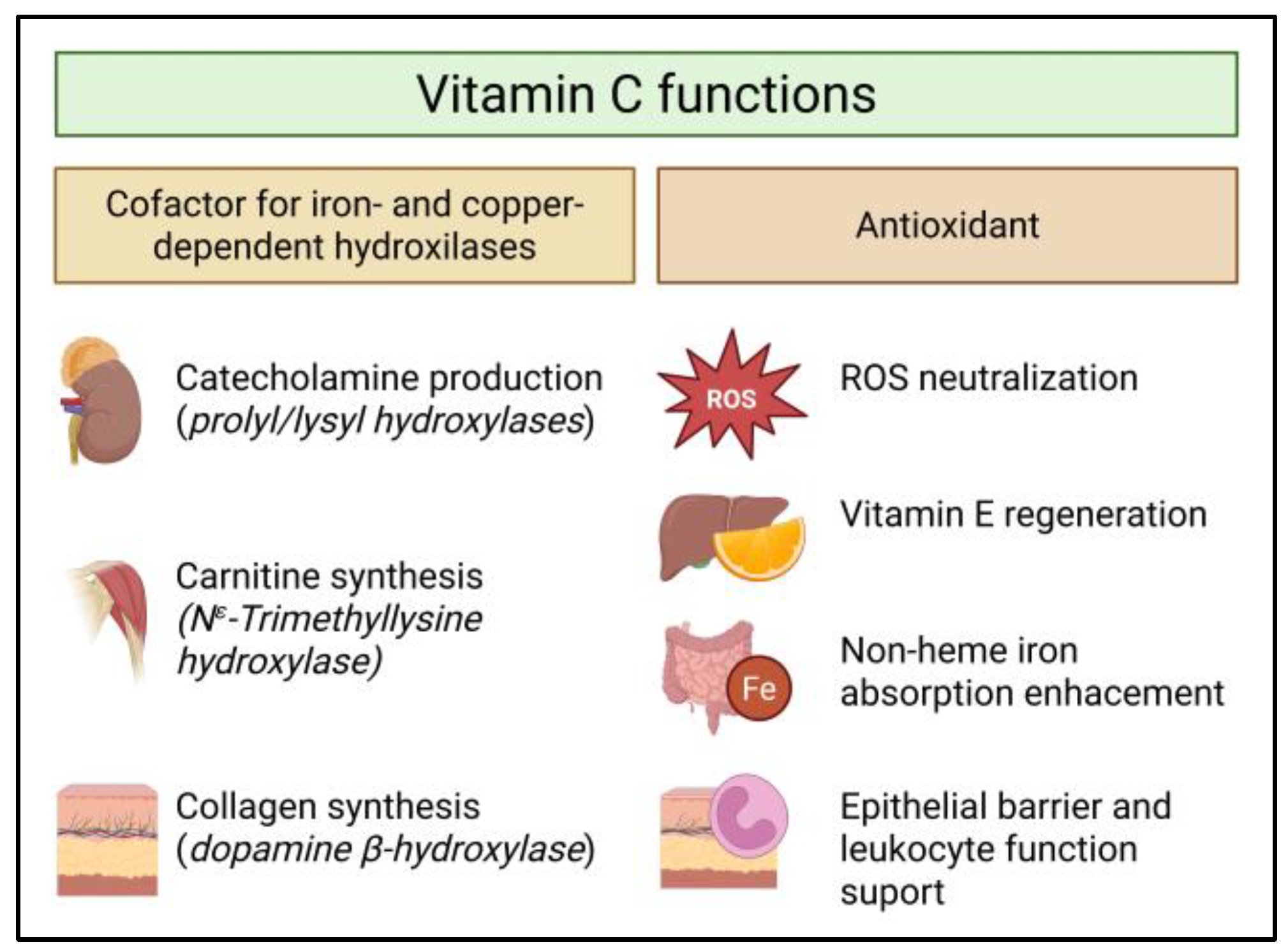

2. Vitamin C

3. Vitamin C Status in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease

3.1. Mechanisms of Vitamin C Deficiency in CKD

3.1.1. Inadequate Dietary Intake

3.1.2. Increases Consumption

3.1.3. Impaired Tubular Reabsorption

3.1.4. Medication

3.1.5. Removal by Dialysis

3.1.6. Benzoic Acid Exposure and Benzene Production

4. Benzoic Acid: Exposure, Pharmacokinetics, and Renal Excretion

5. Benzene Formation and Biological Effects

6. Knowledge Gaps and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| ADI | Acceptable daily intake |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CYP2E1 | Cytochrome P450 2E1 |

| DHA | Dehydroascorbic acid |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (U.S.) |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| JECFA | Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives |

| KTR | Kidney transplant recipient(s) |

| kDa | Kilodalton |

| NIH ODS | National Institutes of Health-Office of Dietary Supplements |

| OAT | Organic anion transporter |

| PD | Peritoneal dialysis |

| PPI | Proton pump inhibitor |

| RDA | Recommended dietary allowance/amount |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| S-PMA | S-phenylmercapturic acid |

| SVCT | Sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter |

| ttMA | Trans trans-Muconic acid |

| UV | Ultraviolet (light) |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Naidu, K.A. Vitamin C in Human Health and Disease Is Still a Mystery? An Overview. Nutr. J. 2003, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flier, J.S.; Underhill, L.H.; Levine, M. New Concepts in the Biology and Biochemistry of Ascorbic Acid. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 314, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Bächinger, H.P. A Molecular Ensemble in the RER for Procollagen Maturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 2479–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulse, J.D.; Ellis, S.R.; Henderson, L.M. Carnitine Biosynthesis. Beta-Hydroxylation of Trimethyllysine by an Alpha-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Mitochondrial Dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1978, 253, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F.E.; May, J.M. Vitamin C Function in the Brain: Vital Role of the Ascorbate Transporter SVCT2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traber, M.G.; Stevens, J.F. Vitamins C and E: Beneficial Effects from a Mechanistic Perspective. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Köberle, M.; Ghashghaeinia, M. Vitamin C-Dependent Uptake of Non-Heme Iron by Enterocytes, Its Impact on Erythropoiesis and Redox Capacity of Human Erythrocytes. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institues of Health Vitamin C Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Vitamin C. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3418. [CrossRef]

- Lykkesfeldt, J.; Tveden-Nyborg, P. The Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin C. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangels, A.R.; Block, G.; Frey, C.M.; Patterson, B.H.; Taylor, P.R.; Norkus, E.P.; Levander, O.A. The Bioavailability to Humans of Ascorbic Acid from Oranges, Orange Juice and Cooked Broccoli Is Similar to That of Synthetic Ascorbic Acid. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Conry-Cantilena, C.; Wang, Y.; Welch, R.W.; Washko, P.W.; Dhariwal, K.R.; Park, J.B.; Lazarev, A.; Graumlich, J.F.; King, J.; et al. Vitamin C Pharmacokinetics in Healthy Volunteers: Evidence for a Recommended Dietary Allowance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3704–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Riordan, H.D.; Hewitt, S.M.; Katz, A.; Wesley, R.A.; Levine, M. Vitamin C Pharmacokinetics: Implications for Oral and Intravenous Use. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004, 140, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Frei, B. Toward a New Recommended Dietary Allowance for Vitamin C Based on Antioxidant and Health Effects in Humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 1086–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gey, K.F. Vitamins E plus C and Interacting Conutrients Required for Optimal Health. BioFactors 1998, 7, 113–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, B.; Lyhne, N.; Pedersen, J.I.; Aro, A.; Thorsdottir, I.; Becker, W. Nordic Nutrition: Recommendations 2012; The Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Volume 40, ISBN 978-92-893-2670-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D.M.; Le, H.N.; Phung, H. The Community Prevalence of Vitamin C Deficiency and Inadequacy—How Does Australia Compare With Other Nations? A Scoping Review. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doseděl, M.; Jirkovský, E.; Macáková, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Javorská, L.; Pourová, J.; Mercolini, L.; Remião, F.; Nováková, L.; Mladěnka, P. Vitamin C—Sources, Physiological Role, Kinetics, Deficiency, Use, Toxicity, and Determination. Nutrients 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevin, D.; Galletly, C. The Neuropsychiatric Effects of Vitamin C Deficiency: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fain, O. Musculoskeletal Manifestations of Scurvy. Jt. Bone Spine 2005, 72, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Morimoto, S.; Okigaki, M.; Seo, M.; Someya, K.; Morita, T.; Matsubara, H.; Sugiura, T.; Iwasaka, T. Decreased Plasma Level of Vitamin C in Chronic Kidney Disease: Comparison between Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorenbos, C.S.; Bolhuis, D.P.; Ipema, K.J.; Duym, E.M.; Westerhuis, R.; Stegmann, M.E.; Franssen, C.F.; Bakker, S.J.; Gomes-Neto, A.W.; Navis, G.; et al. Vitamin C Status across the Spectrum of Chronic Kidney Disease and Healthy Controls: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 122, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsawong, N.; Chawprang, N.; Kittisakmontri, K.; Vittayananan, P.; Srisuwan, K.; Chartapisak, W. Vitamin C Deficiency and Impact of Vitamin C Administration among Pediatric Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2021, 36, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.G.; Gupta, A.K.; Dubey, S.S.; Usha; Sharma, M.R. Ascorbic Acid Status in Uremics. Indian J. Med. Res. 1992, 96, 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Doshida, Y.; Itabashi, M.; Takei, T.; Takino, Y.; Sato, A.; Yumura, W.; Maruyama, N.; Ishigami, A. Reduced Plasma Ascorbate and Increased Proportion of Dehydroascorbic Acid Levels in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Life 2021, 11, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Eide, T.C.; Sogn, E.M.; Berg, K.J.; Sund, R.B. Plasma Ascorbic Acid in Patients Undergoing Chronic Haemodialysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999, 55, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dong, J.; Cheng, X.; Bai, W.; Guo, W.; Wu, L.; Zuo, L. Association between Vitamin C Deficiency and Dialysis Modalities. Nephrology 2012, 17, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, F.O.; Juergensen, P.; Wang, S.; Santacroce, S.; Levine, M.; Kotanko, P.; Levin, N.W.; Handelman, G.J. Hemoglobin and Plasma Vitamin C Levels in Patients on Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2011, 31, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yepes-Calderón, M.; van der Veen, Y.; Martín del Campo, S.F.; Kremer, D.; Sotomayor, C.G.; Knobbe, T.J.; Vos, M.J.; Corpeleijn, E.; de Borst, M.H.; Bakker, S.J.L. Vitamin C Deficiency after Kidney Transplantation: A Cohort and Cross-Sectional Study of the TransplantLines Biobank. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2357–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotomayor, C.G.; Eisenga, M.F.; Gomes Neto, A.W.; Ozyilmaz, A.; Gans, R.O.B.; Jong, W.H.A.d.; Zelle, D.M.; Berger, S.P.; Gaillard, C.A.J.M.; Navis, G.J.; et al. Vitamin C Depletion and All-Cause Mortality in Renal Transplant Recipients. Nutrients 2017, 9, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.C.; Liao, M.T.; Chao, C. Ter Independent Determinants of Appetite Impairment among Patients with Stage 3 or Higher Chronic Kidney Disease: A Prospective Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Qian, Q. Protein Nutrition and Malnutrition in CKD and ESRD. Nutrients 2017, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boslooper-Meulenbelt, K.; van Vliet, I.M.Y.; Gomes-Neto, A.W.; de Jong, M.F.C.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Navis, G.J. Malnutrition According to GLIM Criteria in Stable Renal Transplant Recipients: Reduced Muscle Mass as Predominant Phenotypic Criterion. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3522–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.C.; Kuo, K.-L. Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease. Ren. Replace. Ther. 2018, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, B.P.; McMenamin, E.; Lucas, F.L.; McMonagle, E.; Morrow, J.; Ikizler, T.A.L.P.; Himmelfarb, J. Increased Prevalence of Oxidant Stress and Inflammation in Patients with Moderate to Severe Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; De Smet, R.; Glorieux, G.; Argilés, A.; Baurmeister, U.; Brunet, P.; Clark, W.; Cohen, G.; De Deyn, P.P.; Deppisch, R.; et al. Review on Uremic Toxins: Classification, Concentration, and Interindividual Variability. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1934–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Canaud, B.; Eckardt, K.-U.; Stenvinkel, P.; Wanner, C.; Zoccali, C. Oxidative Stress in End-Stage Renal Disease: An Emerging Threat to Patient Outcome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003, 18, 1272–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witko-Sarsat, V.; Friedlander, M.; Capeillère-Blandin, C.; Nguyen-Khoa, T.; Nguyen, A.T.; Zingraff, J.; Jungers, P.; Descamps-Latscha, B. Advanced Oxidation Protein Products as a Novel Marker of Oxidative Stress in Uremia. Kidney Int. 1996, 49, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.L.; Reed, R.L.; Kuiper, H.C.; Alber, S.; Stevens, J.F. Ascorbic Acid Promotes Detoxification and Elimination of 4-Hydroxy-2(E)-Nonenal in Human Monocytic THP-1 Cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.W.T.; Lopez Gonzalez, E.D.J.; Zoukari, T.; Ki, P.; Shuck, S.C. Methylglyoxal and Its Adducts: Induction, Repair, and Association with Disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1720–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimann, J.G.; Levin, N.W.; Craig, R.G.; Sirover, W.; Kotanko, P.; Handelman, G. Is Vitamin C Intake Too Low in Dialysis Patients? Semin. Dial. 2013, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, M.; Eck, P. Dietary Vitamin C in Human Health. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 83, pp. 281–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lykkesfeldt, J.; Poulsen, H.E. Is Vitamin C Supplementation Beneficial? Lessons Learned from Randomised Controlled Trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, B.; Birlouez-Aragon, I.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Authors’ Perspective: What Is the Optimum Intake of Vitamin C in Humans? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine; Food and Nutrition Board; Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds; Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients; Subcommittee on Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes; Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. Faut-Il Prendre plus de 110 Mg de Vitamine C Par Jour? Phytotherapie 2014, 12, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, L.; Corey, P.N.; El-Sohemy, A. Vitamin C Deficiency in a Population of Young Canadian Adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenuwa, I.; Violet, P.C.; Padayatty, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Adhikari, P.; Smith, S.; Tu, H.; Niyyati, M.; et al. Abnormal Urinary Loss of Vitamin C in Diabetes: Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of a Vitamin C Renal Leak. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebenuwa, I.; Violet, P.C.; Padayatty, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Tu, H.; Wilkins, K.J.; Moore, D.F.; Eck, P.; Schiffmann, R.; Levine, M. Vitamin C Urinary Loss in Fabry Disease: Clinical and Genomic Characteristics of Vitamin C Renal Leak. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.F.; Eisenstein, A.B.; Mottola, O.M.; Mittal, A.K. The Effect of Dialysis on Plasma and Tissue Levels of Vitamin C. ASAIO J. 1972, 18, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirover, W.D.; Liu, Y.; Logan, A.; Hunter, K.; Benz, R.L.; Prasad, D.; Avila, J.; Venkatchalam, T.; Weisberg, L.S.; Handelman, G.J. Plasma Ascorbic Acid Concentrations in Prevalent Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease on Hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2015, 25, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deicher, R.; Ziai, F.; Bieglmayer, C.; Schillinger, M.; Hörl, W.H. Low Total Vitamin C Plasma Level Is a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Rumsey, S.C.; Daruwala, R.; Park, J.B.; Wang, Y. Criteria and Recommendations for Vitamin C Intake. JAMA 1999, 281, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clase, C.M.; Ki, V.; Holden, R.M. Water-Soluble Vitamins in People with Low Glomerular Filtration Rate or on Dialysis: A Review. Semin. Dial. 2013, 26, 546–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Comparison of the Effect of Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis in the Treatment of End-Stage Renal Disease. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 39, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Code of Federal Regulations 184.1733 Sodium Beanzoate. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-184/section-184.1733 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Axel, W. Benzoic Acid and Sodium Benzoate; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; ISBN 92-4-153026-X. [Google Scholar]

- TRS 1037 JECFA 92/5; Benzoates. Thee Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources Added to Food. Scientific Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Benzoic Acid (E 210), Sodium Benzoate (E 211), Potassium Benzoate (E 212) and Calcium Benzoate (E 213) as Food Additives. EFSA J. 2016, 14, 4433. [CrossRef]

- Sieber, R.; Bütikofer, U.; Bosset, J.O. Benzoic Acid as a Natural Compound in Cultured Dairy Products and Cheese. Int. Dairy. J. 1995, 5, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, K.; Pizzurro, D.M.; Lewandowski, T.A.; Goodman, J.E. Pharmacokinetic Data Reduce Uncertainty in the Acceptable Daily Intake for Benzoic Acid and Its Salts. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 89, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohwer, J.M.; Schutte, C.; van der Sluis, R. Functional Characterisation of Three Glycine N-Acyltransferase Variants and the Effect on Glycine Conjugation to Benzoyl–CoA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Ishizaki, T. Dose-Dependent Pharmacokinetics of Benzoic Acid Following Oral Administration of Sodium Benzoate to Humans. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1991, 41, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riihimäki, V. Conjugation and Urinary Excretion of Toluene and M-Xylene Metabolites in a Man. Scand. J. Work. Env. Health 1979, 5, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Adiga, A.; Novack, J.; Etinger, A.; Chinitz, L.; Slater, J.; de Loor, H.; Meijers, B.; Holzman, R.S.; Lowenstein, J. The Renal Transport of Hippurate and Protein-Bound Solutes. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA/690/R-05/008F; Provisional Peer-Reviewed Toxicity Values for Benzoic Acid. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Mitch, W.E.; Brusilow, S. Benzoate-Induced Changes in Glycine and Urea Metabolism in Patients with Chronic Renal Failure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1982, 222, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spustová, V.; Gajdos, M.; Opatrný, K.; Stefíková, K.; Dzúrik, R. Serum Hippurate and Its Excretion in Conservatively Treated and Dialysed Patients with Chronic Renal Failure. Physiol. Res. 1991, 40, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gardner, L.K.; Lawrence, G.D. Benzene Production from Decarboxylation of Benzoic Acid in the Presence of Ascorbic Acid and a Transition-Metal Catalyst. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salviano dos Santos, V.P.; Medeiros Salgado, A.; Guedes Torres, A.; Signori Pereira, K. Benzene as a Chemical Hazard in Processed Foods. Int. J. Food Sci. 2015, 2015, 545640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Questions and Answers on the Occurrence of Benzene in Soft Drinks and Other Beverages; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022.

- Medeiros Vinci, R.; De Meulenaer, B.; Andjelkovic, M.; Canfyn, M.; Van Overmeire, I.; Van Loco, J. Factors Influencing Benzene Formation from the Decarboxylation of Benzoate in Liquid Model Systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12975–12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs Volume 120: Benzene; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, B. Hydroxyl Radical and Its Scavengers in Health and Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2011, 2011, 809696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressman, J.B.; Berardi, R.R.; Dermentzoglou, L.C.; Russell, T.L.; Schmaltz, S.P.; Barnett, J.L.; Jarvenpaa, K.M. Upper Gastrointestinal (GI) PH in Young, Healthy Men and Women. Pharm. Res. 1990, 7, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, H. The Acid Gate in the Lysosome. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1368–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.M.; Strader, E.R.; Truitt, E.B. The Relation between the Structure of Halogenated Benzoic Acids and the Depletion of Adrenal Ascorbic Acid Content. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1954, 112, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, J.; Jaques, L.B. A Comparative Study of the Effect of a Series of Aromatic Acids on the Ascorbic Acid Content of the Adrenal Gland. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1953, 107, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Exposure to Benzene: A Major Public Health Concern; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Benzene; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, Georgia, 2024.

- Galbraith, D.; Gross, S.A.; Paustenbach, D. Benzene and Human Health: A Historical Review and Appraisal of Associations with Various Diseases. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010, 40, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Tang, L.; Li, D.; Xie, J.; Sun, Y.; Tian, Y. Long-Term Exposure to Low Concentrations of Ambient Benzene and Mortality in a National English Cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, P.J.; Diachenko, G.W.; Perfetti, G.A.; McNeal, T.P.; Hiatt, M.H.; Morehouse, K.M. Survey Results of Benzene in Soft Drinks and Other Beverages by Headspace Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Summary of an Investigation of the Reliability of Benzene Results from the Total Diet Study; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022.

- May, J.M. The SLC23 Family of Ascorbate Transporters: Ensuring That You Get and Keep Your Daily Dose of Vitamin C. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.K.; Bush, K.T.; Martovetsky, G.; Ahn, S.-Y.; Liu, H.C.; Richard, E.; Bhatnagar, V.; Wu, W. The Organic Anion Transporter (OAT) Family: A Systems Biology Perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 83–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boogaard, P.J.; van Sittert, N.J. Biological Monitoring of Exposure to Benzene: A Comparison between S-Phenylmercapturic Acid, Trans,Trans-Muconic Acid, and Phenol. Occup. Env. Med. 1995, 52, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisel, C.; Yu, R.; Roy, A.; Georgopoulos, P. Biomarkers of Environmental Benzene Exposure. Env. Health Perspect. 1996, 104, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, P.; Gulyassy, P.; Stanfel, L.; Depner, T. Plasma Hippurate in Renal Failure: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method and Clinical Application. Nephron 1987, 47, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.E.; Escudier, M.P.; Patel, P.; Challacombe, S.J.; Sanderson, J.D.; Lomer, M.C.E. Review Article: Cinnamon- and Benzoate-Free Diet as a Primary Treatment for Orofacial Granulomatosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 34, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yepes-Calderón, M.; Doorenbos, C.S.E.; Corpeleijn, E.; Franssen, C.F.M.; Vos, M.J.; Touw, D.J.; Mariat, C.; de Weerd, A.E.; Bakker, S.J.L. Vitamin C and Benzoic Acid Intake in Patients with Kidney Disease: Is There Risk of Benzene Exposure? Nutrients 2026, 18, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010132

Yepes-Calderón M, Doorenbos CSE, Corpeleijn E, Franssen CFM, Vos MJ, Touw DJ, Mariat C, de Weerd AE, Bakker SJL. Vitamin C and Benzoic Acid Intake in Patients with Kidney Disease: Is There Risk of Benzene Exposure? Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleYepes-Calderón, Manuela, Caecilia S. E. Doorenbos, Eva Corpeleijn, Casper F. M. Franssen, Michel J. Vos, Daan J. Touw, Christophe Mariat, Annelies E. de Weerd, and Stephan J. L. Bakker. 2026. "Vitamin C and Benzoic Acid Intake in Patients with Kidney Disease: Is There Risk of Benzene Exposure?" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010132

APA StyleYepes-Calderón, M., Doorenbos, C. S. E., Corpeleijn, E., Franssen, C. F. M., Vos, M. J., Touw, D. J., Mariat, C., de Weerd, A. E., & Bakker, S. J. L. (2026). Vitamin C and Benzoic Acid Intake in Patients with Kidney Disease: Is There Risk of Benzene Exposure? Nutrients, 18(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010132