Comprehensive Effects of Melatonin Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Certainty Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Meta-Analysis

3.3.1. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Anthropometric Parameters

3.3.2. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Glycemic Parameters

3.3.3. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Lipid Parameters

3.3.4. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Blood Pressure

3.3.5. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Oxidative Stress Parameters

3.3.6. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Inflammatory Parameters

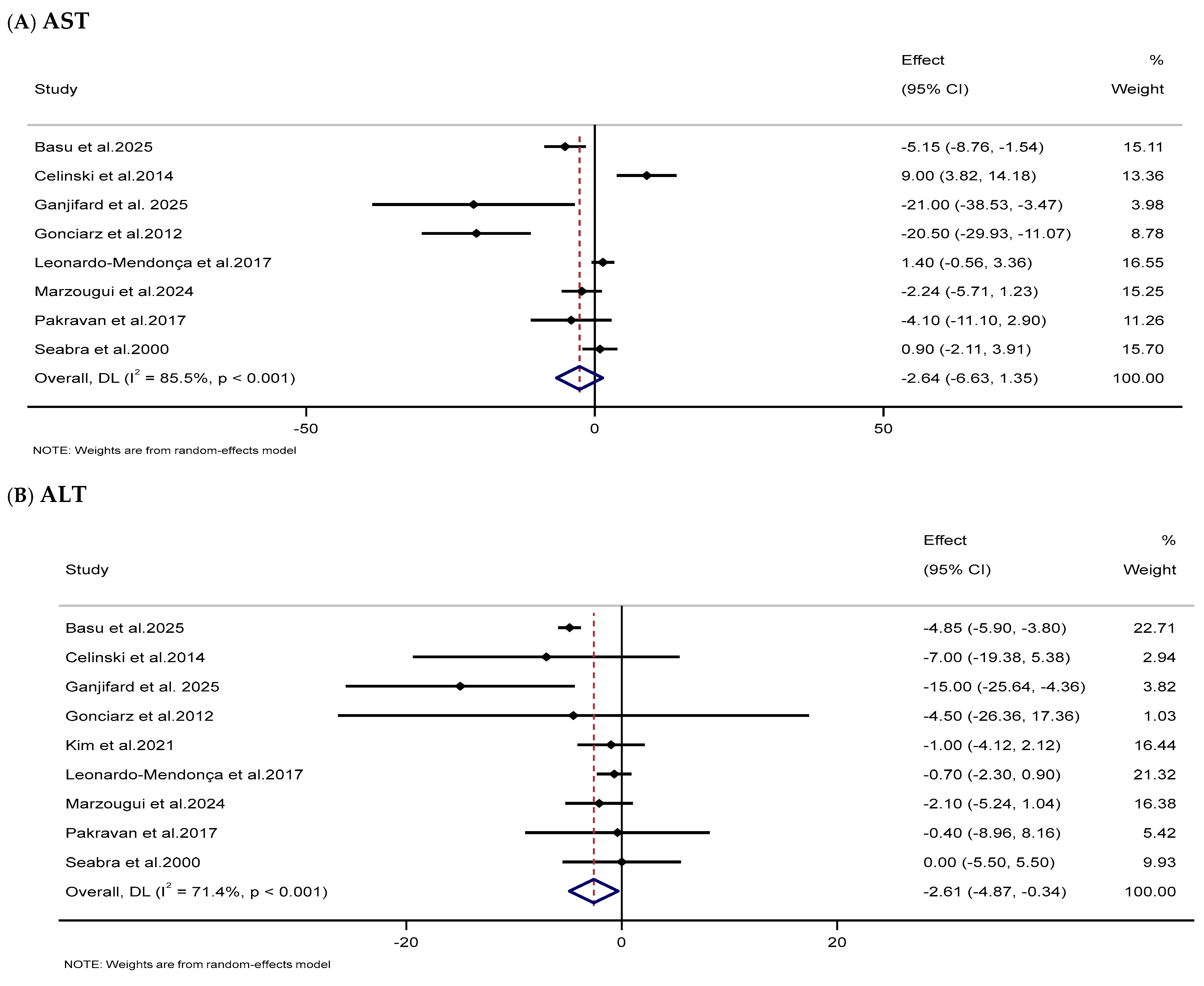

3.3.7. Impacts of Melatonin Supplementation on Liver Function Markers

3.4. Risk of Bias Evaluation

3.5. GRADE

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

3.7. Publication Bias

3.8. Linear and Nonlinear Dose–Response Associations

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Findings in the Context of Existing Literature

4.3. Possible Underlying Mechanisms

4.4. Safety of Melatonin Supplements

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| WC | Waist circumference |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| HC | Hip circumference |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| FBG | Fasting blood glucose |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance |

| TAC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| WMD | Weighted mean difference |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| NASH | Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| OB | Obesity |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| IRI | Ischemia and reperfusion injury |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| DN | Diabetic nephropathy |

| SGAs | Second-generation antipsychotics |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| OW | Overweight |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| BW | Body weight |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| USA | United States of America |

| GRADE | Grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation |

| RoB | Risk of bias |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| CMRF | Cardiometabolic risk factor |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CMH | Cardiometabolic health |

| CMR | Cardiometabolic risk |

| CMD | Cardiometabolic disease |

| FI | Fasting insulin |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Gjermeni, E.; Fiebiger, R.; Bundalian, L.; Garten, A.; Schöneberg, T.; Le Duc, D.; Blüher, M. The impact of dietary interventions on cardiometabolic health. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Rawish, E.; Nording, H.M.; Langer, H.F. Inflammation in metabolic and cardiovascular disorders—Role of oxidative stress. Life 2021, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlov, A.L.; Figtree, G.A.; Horowitz, J.D.; Ngo, D.T. Interplay between oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiometabolic syndrome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 8254590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative stress: Harms and benefits for human health. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, V.P.; Feehan, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Inflammation: The cause of all diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, B.S.; Patil, J.K.; Chaudhari, H.S.; Patil, B.S. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Obesity: Insights into Mechanism and Therapeutic Targets. Proceedings 2025, 119, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg Sibony, R.; Segev, O.; Dor, S.; Raz, I. Overview of oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashkow, F.J. Oxidative stress and inflammation in heart disease: Do antioxidants have a role in treatment and/or prevention? Int. J. Inflamm. 2011, 2011, 514623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klisic, A.; Kavaric, N.; Ninic, A.; Kotur-Stevuljevic, J. Oxidative stress and cardiometabolic biomarkers in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Asbaghi, O.; Afrisham, R.; Farrokhi, V.; Jadidi, Y.; Mofidi, F.; Ashtary-Larky, D. Impacts of Supplementation with Silymarin on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Heshmati, J.; Baziar, N.; Ziaei, S.; Farsi, F.; Ebrahimi, S.; Mobaderi, T.; Mohammadi, T.; Mir, H. Impacts of supplementation with pomegranate on cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Alaghemand, N.; Alavi, I.; Erfanian-Salim, M.; Pirayvatlou, P.S.; Ettehad, Y.; Borzabadi, A.; Mehrbod, M.; Asbaghi, O. Effects of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, in press, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammisotto, V.; Nocella, C.; Bartimoccia, S.; Sanguigni, V.; Francomano, D.; Sciarretta, S.; Pastori, D.; Peruzzi, M.; Cavarretta, E.; D’Amico, A.; et al. The role of antioxidants supplementation in clinical practice: Focus on cardiovascular risk factors. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Fulop, T.; Khalil, A.; Ebrahimi, S.; Hasani, M.; Ziaei, S.; Farsi, F.; Mirtaheri, E.; Afsharianfar, M.; Heshmati, J. Does supplementation with pine bark extract improve cardiometabolic risk factors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ziaei, S.; Morvaridi, M.; Hasani, M.; Mirtaheri, E.; Farsi, F.; Ebrahimi, S.; Daneshzad, E.; Heshmati, J. Impacts of Curcumin Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Dose−Response Meta-Analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Asbaghi, O.; Farrokhi, V.; Jadidi, Y.; Mofidi, F.; Mohammadian, M.; Afrisham, R. Effects of silymarin supplementation on liver and kidney functions: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 2572–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzeh, F.S.; Kamfar, W.W.; Ghaith, M.M.; Alsafi, R.T.; Shamlan, G.; Ghabashi, M.A.; Farrash, W.F.; Alyamani, R.A.; Alazzeh, A.Y.; Alkholy, S.O.; et al. Unlocking the health benefits of melatonin supplementation: A promising preventative and therapeutic strategy. Medicine 2024, 103, e39657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, C.; Suzen, S. Antioxidant properties of melatonin and its potential action in diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamfar, W.W.; Khraiwesh, H.M.; Ibrahim, M.O.; Qadhi, A.H.; Azhar, W.F.; Ghafouri, K.J.; Alhussain, M.H.; Aldairi, A.F.; AlShahrani, A.M.; Alghannam, A.F.; et al. Comprehensive review of melatonin as a promising nutritional and nutraceutical supplement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, A.; Suzuki, N. Receptor-mediated and receptor-independent actions of melatonin in vertebrates. Zool. Sci. 2024, 41, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S.M.; Wani, A.B.; Bhat, R.R.; Rehman, M.U. Melatonin and health: Insights of melatonin action, biological functions, and associated disorders. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 2437–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.N.; Almieda Chuffa, L.G.d.; Silva, D.G.H.d.S.; Rosales Corral, S. Intrinsically synthesized melatonin in mitochondria and factors controlling its production. Histol. Histopathol. 2025, 40, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.; Tan, D.-X.; Chuffa, L.G.d.A.; da Silva, D.G.H.; Slominski, A.T.; Steinbrink, K.; Kleszczynski, K. Dual sources of melatonin and evidence for different primary functions. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1414463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Dietary sources and bioactivities of melatonin. Nutrients 2017, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under promises but over delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claustrat, B.; Leston, J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie 2015, 61, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; Fougerou, C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, functions and therapeutic benefits. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, R.M.; Reiter, R.J.; Schlabritz-Loutsevitch, N.; Ostrom, R.S.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin membrane receptors in peripheral tissues: Distribution and functions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 351, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, J.; Reiter, R.J.; Kaarniranta, K. Melatonin in retinal physiology and pathology: The case of age-related macular degeneration. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6819736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Q.; Fichna, J.; Bashashati, M.; Li, Y.-Y.; Storr, M. Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2011, 17, 3888–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.; Terron, M.P.; Flores, L.J.; Koppisepi, S. Medical implications of melatonin: Receptor-mediated and receptor-independent actions. Adv. Med. Sci. 2007, 52, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin’s metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.M.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin: A well-documented antioxidant with conditional pro-oxidant actions. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin and its metabolites vs oxidative stress: From individual actions to collective protection. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracioli-Oda, E.; Qawasmi, A.; Bloch, M.H. Meta-analysis: Melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.R.; Maldonado, M.D. Immunoregulatory properties of melatonin in the humoral immune system: A narrative review. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 269, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejska, R.; Woźniak, A.; Bilski, R.; Wesołowski, R.; Kupczyk, D.; Porzych, M.; Wróblewska, W.; Pawluk, H. Melatonin—A Powerful Oxidant in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konturek, S.; Konturek, P.; Brzozowski, T.; Bubenik, G. Role of melatonin in upper gastrointestinal tract. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2007, 58, 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Khorshidi, M.; Emami, M.; Janmohammadi, P.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Mousavi, S.M.; Mohammed, S.H.; Saedisomeolia, A.; Alizadeh, S. Melatonin supplementation and pro-inflammatory mediators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Bhutani, S.; Kim, C.H.; Irwin, M.R. Anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 93, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radogna, F.; Diederich, M.; Ghibelli, L. Melatonin: A pleiotropic molecule regulating inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibowitz, A.; Peleg, E.; Sharabi, Y.; Shabtai, Z.; Shamiss, A.; Grossman, E. The role of melatonin in the pathogenesis of hypertension in rats with metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008, 21, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nduhirabandi, F.; Du Toit, E.F.; Blackhurst, D.; Marais, D.; Lochner, A. Chronic melatonin consumption prevents obesity-related metabolic abnormalities and protects the heart against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury in a prediabetic model of diet-induced obesity. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 50, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Lugo, M.J.; Cano, P.; Jiménez-Ortega, V.; Fernández-Mateos, M.P.; Scacchi, P.A.; Cardinali, D.P.; Esquifino, A.I. Melatonin effect on plasma adiponectin, leptin, insulin, glucose, triglycerides and cholesterol in normal and high fat–fed rats. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 49, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolden-Hanson, T.; Mitton, D.; McCants, R.; Yellon, S.; Wilkinson, C.; Matsumoto, A.; Rasmussen, D. Daily melatonin administration to middle-aged male rats suppresses body weight, intraabdominal adiposity, and plasma leptin and insulin independent of food intake and total body fat. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamitri, A.; Jockers, R. Melatonin in type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Abreu-Gonzalez, P.; Baez-Ferrer, N.; Reiter, R.J.; Avanzas, P.; Hernandez-Vaquero, D. Melatonin and cardioprotection in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 635083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minari, T.P.; Pisani, L.P. Melatonin supplementation: New insights into health and disease. Sleep Breath. 2025, 29, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino, F.M.; Figueiredo, L.M.; Nunes, B.P. Effects of melatonin supplementation on diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4595–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z. Effects of melatonin supplementation on insulin levels and insulin resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Horm. Metab. Res. 2021, 53, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayazi, F.; Kheirouri, S.; Alizadeh, M. Exploring effects of melatonin supplementation on insulin resistance: An updated systematic review of animal and human studies. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2024, 18, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Lv, X.; Ai, S.; Zhang, D.; Lu, H. The effect of melatonin supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1572613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, A.; Ghaedi, E.; Moradi, S.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Ghavami, A.; Kafeshani, M. Effects of melatonin supplementation on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Horm. Metab. Res. 2019, 51, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajdi, M.; Moeinolsadat, S.; Noshadi, N.; Tabrizi, F.P.F.; Khajeh, M.; Abbasalizad-Farhangi, M.; Alipour, B. Effect of melatonin supplementation on body composition and blood pressure in adults: A systematic review and Dose–Response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.P.; Poon, P.; Yu, C.P.; Lee, V.W.Y.; Chung, V.C.H.; Wong, S.Y.S. Controlled-release oral melatonin supplementation for hypertension and nocturnal hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2022, 24, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vecchis, R.; Paccone, A.; Di Maio, M. Property of melatonin of acting as an antihypertensive agent to antagonize nocturnal high blood pressure: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Stat. Med. Res 2019, 8, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, E.; Laudon, M.; Zisapel, N. Effect of melatonin on nocturnal blood pressure: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2011, 7, 577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Delpino, F.M.; Figueiredo, L.M. Melatonin supplementation and anthropometric indicators of obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition 2021, 91–92, 111399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, S.-A.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Reza Mohammadi, M.; Keshtkar, A.-A.; Hosseini, S.; Reza Eshraghian, M.; Ahmadi Motlagh, T.; Alipour, R.; Ali Keshavarz, S. Role of melatonin in body weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 3445–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loloei, S.; Sepidarkish, M.; Heydarian, A.; Tahvilian, N.; Khazdouz, M.; Heshmati, J.; Pouraram, H. The effect of melatonin supplementation on lipid profile and anthropometric indices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 1901–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi-Sartang, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Mazloom, Z. Effects of melatonin supplementation on blood lipid concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1943–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, A.; Salimi, Z.; Hosseini, S.A.; Hormoznejad, R.; Jafarirad, S.; Bahrami, M.; Asadi, M. The effect of melatonin supplementation on liver indices in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morvaridzadeh, M.; Sadeghi, E.; Agah, S.; Nachvak, S.M.; Fazelian, S.; Moradi, F.; Persad, E.; Heshmati, J. Effect of melatonin supplementation on oxidative stress parameters: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Barzegari, M.; Aghapour, B.; Adeli, S.; Khademi, F.; Musazadeh, V.; Jamilian, P.; Jamilian, P.; Fakhr, L.; Chehregosha, F.; et al. Melatonin effectiveness in amelioration of oxidative stress and strengthening of antioxidant defense system: Findings from a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 48, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbaninejad, P.; Sheikhhossein, F.; Djafari, F.; Tijani, A.J.; Mohammadpour, S.; Shab-Bidar, S. Effects of melatonin supplementation on oxidative stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2020, 41, 20200030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, R.M.; Rashno, M.; Bahreiny, S.S. Effects of melatonin supplementation on markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begg, C.B.; Berlin, J.A. Publication bias: A problem in interpreting medical data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Stat. Soc.) 1988, 151, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.N. Interpreting and Visualizing Regression Models Using Stata; Stata Press College Station: College Station, TX, USA, 2012; Volume 558. [Google Scholar]

- Abood, S.J.; Abdulsahib, W.K.; Hussain, S.A.; Ismail, S.H. Melatonin potentiates the therapeutic effects of metformin in women with metabolic syndrome. Sci. Pharm. 2020, 88, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agahi, M.; Akasheh, N.; Ahmadvand, A.; Akbari, H.; Izadpanah, F. Effect of melatonin in reducing second-generation antipsychotic metabolic effects: A double blind controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2018, 12, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Mostafavi, S.-A.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Chamari, M. Melatonin effects in women with comorbidities of overweight, depression, and sleep disturbance: A randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. Sleep Med. Res. 2022, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lami, H.C.A. Melatonin Improves Lipid Profile and Ameliorates Lipid Peroxidation in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Al Mustansiriyah J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 18, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Alamdari, N.M.; Mahdavi, R.; Roshanravan, N.; Yaghin, N.L.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Faramarzi, E. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial related to the effects of melatonin on oxidative stress and inflammatory parameters of obese women. Horm. Metab. Res. 2015, 47, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Karandish, M.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Heidari, L.; Nikbakht, R.; Babaahmadi Rezaei, H.; Mousavi, R. Metabolic and hormonal effects of melatonin and/or magnesium supplementation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Z.; Keyhanian, N.; Ghaderkhani, S.; Dashti-Khavidaki, S.; Shoormasti, R.S.; Pourpak, Z. A pilot study on controlling coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) inflammation using melatonin supplement. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 20, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstrup, A.K.; Rejnmark, L. Effects of melatonin on blood pressure, arterial stiffness and quality of life in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2024, 81, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, D.-M.; Sufaru, I.-G.; Martu, M.-A.; Mocanu, R.; Luchian, I.; Scutariu, M.-M.; Pasarin, L.; Martu, S. Study on the effects of melatonin administration on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in patients with type II diabetes and periodontal disease. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 14, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, A.; Kalalian Moghadam, H.; Atashi, A.; Aghayan, S.S.; Emamian, M.H. Melatonin effect on mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells in methamphetamine abuser, a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2025, 56, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Cheraghpour, M.; Jafarirad, S.; Alavinejad, P.; Asadi, F.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Yari, Z. The effect of melatonin on treatment of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized double blind clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, M.; Cheraghpour, M.; Jafarirad, S.; Alavinejad, P.; Cheraghian, B. The role of melatonin supplement in metabolic syndrome: A randomized double blind clinical trial. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 49, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Majee, A.M.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Effect of melatonin supplementation on exercise-induced alterations in haematological parameters and liver function markers in sedentary young men of Kolkata, India. Sport Sci. Health 2025, 21, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyar, H.; Gholinezhad, H.; Moradi, L.; Salehi, P.; Abadi, F.; Ravanbakhsh, M.; Zare Javid, A. The effects of melatonin supplementation in adjunct with non-surgical periodontal therapy on periodontal status, serum melatonin and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with chronic periodontitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bazyar, H.; Zare Javid, A.; Bavi Behbahani, H.; Moradi, F.; Moradi Poode, B.; Amiri, P. Consumption of melatonin supplement improves cardiovascular disease risk factors and anthropometric indices in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celinski, K.; Konturek, P.C.; Slomka, M.; Cichoz-Lach, H.; Brzozowski, T.; Konturek, S.J.; Korolczuk, A. Effects of treatment with melatonin and tryptophan on liver enzymes, parameters of fat metabolism and plasma levels of cytokines in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease--14 months follow up. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 65, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki, C.; Kaczka, A.; Gasiorowska, A.; Fichna, J.; Chojnacki, J.; Brzozowski, T. The effect of long-term melatonin supplementation on psychosomatic disorders in postmenopausal women. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 69, 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki, C.; Walecka-Kapica, E.; Klupinska, G.; Pawlowicz, M.; Blonska, A.; Chojnacki, J. Effects of fluoxetine and melatonin on mood, sleep quality and body mass index in postmenopausal women. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki, C.; Wisniewska-Jarosinska, M.; Walecka-Kapica, E.; Klupinska, G.; Jaworek, J.; Chojnacki, J. Evaluation of melatonin effectiveness in the adjuvant treatment of ulcerative colitis. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2011, 62, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna, R.; Santamaria, A.; Giorgianni, G.; Vaiarelli, A.; Gullo, G.; Di Bari, F.; Benvenga, S. Myo-inositol and melatonin in the menopausal transition. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2017, 33, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esalatmanesh, K.; Loghman, A.; Esalatmanesh, R.; Soleimani, Z.; Khabbazi, A.; Mahdavi, A.M.; Mousavi, S.G.A. Effects of melatonin supplementation on disease activity, oxidative stress, inflammatory, and metabolic parameters in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 3591–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrokhian, A.; Tohidi, M.; Ahanchi, N.S.; Khalili, D.; Niroomand, M.; Mahboubi, A.; Derakhshi, A.; Abbasinazari, M.; Hadaegh, F. Effect of bedtime melatonin administration in patients with type 2 diabetes: A triple-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR 2019, 18, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, C.M.; Mackay, G.M.; Stoy, N.; Stone, T.W.; Darlington, L.G. Inflammatory status and kynurenine metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis treated with melatonin. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 64, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganjifard, M.; Ghafari, S.; Sahebnasagh, A.; Esmaeili, M.; Amirabadizadeh, A.R.; Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Askari, P.; Avan, R. Evaluation of the effect of melatonin on patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICU: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Vacunas 2025, 26, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi-Zefrehi, H.; Seif, F.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Ayashi, S.; Jafarirad, S.; Niknam, Z.; Rafiee, M.H.; Babaahmadi-Rezaei, H. Impact of the supplementation of melatonin on oxidative stress marker and serum endothelin-1 in patients with metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2024, 44, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Gonciarz, M.; Gonciarz, Z.; Bielanski, W.; Mularczyk, A.; Konturek, P.; Brzozowski, T.; Konturek, S. The effects of long-term melatonin treatment on plasma liver enzymes levels and plasma concentrations of lipids and melatonin in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A pilot study. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 63, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A.; Terry, P.D.; Superak, H.M.; Nell-Dybdahl, C.L.; Chowdhury, R.; Phillips, L.S.; Kutner, M.H. Melatonin supplementation to treat the metabolic syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 6, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, E.; Laudon, M.; Yalcin, R.; Zengil, H.; Peleg, E.; Sharabi, Y.; Kamari, Y.; Shen-Orr, Z.; Zisapel, N. Melatonin reduces night blood pressure in patients with nocturnal hypertension. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannemann, J.; Laing, A.; Middleton, B.; Schwedhelm, E.; Marx, N.; Federici, M.; Kastner, M.; Skene, D.J.; Böger, R. Effect of oral melatonin treatment on insulin resistance and diurnal blood pressure variability in night shift workers. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 199, 107011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, Z.; Al-Atrakji, M.; Alsaaty, M.; Abdulnafa, Z.; Mehuaiden, A. The effect of melatonin on C-reactive protein, serum ferritin and D-dimer in COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Drug Deliv. Technol. 2022, 12, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, S.G.; Heshmat-Ghahdarijani, K.; Khosrawi, S.; Garakyaraghi, M.; Shafie, D.; Roohafza, H.; Mansourian, M.; Azizi, E.; Gheisari, Y.; Sadeghi, M. Effect of melatonin supplementation on endothelial function in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Clin. Cardiol. 2021, 44, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jallouli, S.; Jallouli, D.; Damak, M.; Sakka, S.; Ghroubi, S.; Mhiri, C.; Driss, T.; de Marco, G.; Ayadi, F.; Hammouda, O. 12-week melatonin intake attenuates cardiac autonomic dysfunction and oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Metab. Brain Dis. 2025, 40, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmard, S.H.; Heshmat-Ghahdarijani, K.; Mirmohammad-Sadeghi, M.; Sonbolestan, S.A.; Ziayi, A. The effect of melatonin on endothelial dysfunction in patient undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2016, 5, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, F.; Bizheh, N.; Ghahremani Moghaddam, M. Interactive effect of melatonin and combined training on some components of physical fitness and serum levels of malondialdhyde in postmenopausal women with type 2. Iran. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Infertil. 2019, 22, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kang, H.-T.; Lee, D.-C. Melatonin supplementation for six weeks had no effect on arterial stiffness and mitochondrial DNA in women aged 55 years and older with insomnia: A double-blind randomized controlled study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarczyk, M.P.; Lassila, H.C.; O’Neil, C.K.; D’Amico, F.; Enderby, L.T.; Witt-Enderby, P.A.; Balk, J.L. Melatonin osteoporosis prevention study (MOPS): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examining the effects of melatonin on bone health and quality of life in perimenopausal women. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 52, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, E.S.; Kampmann, U.; Pedersen, M.G.; Christensen, L.L.; Jessen, N.; Møller, N.; Støy, J. Three months of melatonin treatment reduces insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes—A randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 73, e12809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo-Mendonça, R.C.; Ocaña-Wilhelmi, J.; de Haro, T.; de Teresa-Galván, C.; Guerra-Hernández, E.; Rusanova, I.; Fernández-Ortiz, M.; Sayed, R.K.; Escames, G.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D. The benefit of a supplement with the antioxidant melatonin on redox status and muscle damage in resistance-trained athletes. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, C.S.; Nehme, P.X.; Saraiva, S.; D’Aurea, C.V.; Amaral, F.G.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Marqueze, E.C.; Moreno, C.R. Dietary Intake and Body Composition of Fixed-Shift Workers During the Climacteric: An Intervention Study with Exogenous Melatonin. Obesities 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzougui, H.; Ben Dhia, I.; Mezghani, I.; Maaloul, R.; Toumi, S.; Kammoun, K.; Chaabouni, M.N.; Ayadi, F.; Ben Hmida, M.; Turki, M.; et al. The Synergistic Effect of Intradialytic Concurrent Training and Melatonin Supplementation on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Hemodialysis Patients: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modabbernia, A.; Heidari, P.; Soleimani, R.; Sobhani, A.; Roshan, Z.A.; Taslimi, S.; Ashrafi, M.; Modabbernia, M.J. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 53, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, S.; Rastmanesh, R.; Jahangir, F.; Amiri, Z.; Djafarian, K.; Mohsenpour, M.A.; Hassanipour, S.; Ghaffarian-Bahraman, A. Melatonin supplementation and anthropometric indices: A randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 3502325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, R.; Alizadeh, M.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Heidari, L.; Nikbakht, R.; Babaahmadi Rezaei, H.; Karandish, M. Effects of melatonin and/or magnesium supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatian-Asl, M.; Ghorbanihaghjo, A.; Malek Mahdavi, A.; Khabbazi, A.; Hajialilo, M.; Ghojazadeh, M. Effects of melatonin supplementation on serum oxidative stress markers and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, D.; Mota, R.; Machado, M.; Pereira, E.; De Bruin, V.; De Bruin, P. Effect of melatonin administration on subjective sleep quality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2008, 41, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Franco, M.; Planells, E.; Quintero, B.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D.; Rusanova, I.; Escames, G.; Molina-López, J. Effect of melatonin supplementation on antioxidant status and DNA damage in high intensity trained athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, H.; Ahmadian, M.; Fani, A.; Aghaee, D.; Brumanad, S.; Pakzad, B. The effects of melatonin in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2017, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panah, F.; Ghorbanihaghjo, A.; Argani, H.; Haiaty, S.; Rashtchizadeh, N.; Hosseini, L.; Dastmalchi, S.; Rezaeian, R.; Alirezaei, A.; Jabarpour, M.; et al. The effect of oral melatonin on renal ischemia–reperfusion injury in transplant patients: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Transpl. Immunol. 2019, 57, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechciński, T.; Trzos, E.; Wierzbowska-Drabik, K.; Krzemińska-Pakuła, M.; Kurpesa, M. Melatonin for nondippers with coronary artery disease: Assessment of blood pressure profile and heart rate variability. Hypertens. Res. 2010, 33, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvanfar, M.R.; Heshmati, G.; Chehrei, A.; Haghverdi, F.; Rafiee, F.; Rezvanfar, F. Effect of bedtime melatonin consumption on diabetes control and lipid profile. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2017, 37, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, A.E.; Rubino, F.M.; Caroli, D.; Bondesan, A.; Mai, S.; Cella, S.G.; Centofanti, L.; Paroni, R.; Sartorio, A. Effects of melatonin on exercise-induced oxidative stress in adults with obesity undergoing a multidisciplinary body weight reduction program. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindone, J.P.; Achacoso, R. Effect of melatonin on serum lipids in patients with hypercholesterolemia: A pilot study. Am. J. Ther. 1997, 4, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Peroni, G.; Gasparri, C.; Infantino, V.; Nichetti, M.; Cuzzoni, G.; Spadaccini, D.; Perna, S. Is a combination of melatonin and amino acids useful to sarcopenic elderly patients? A randomized trial. Geriatrics 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Nassiri, A.; Hakemi, M.S.; Hosseini, F.; Pourrezagholie, F.; Naeini, F.; Niri, A.N.; Imani, H.; Mohammadi, H. Effects of melatonin supplementation on oxidative stress, and inflammatory biomarkers in diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, A.L.; Ortiz, G.G.; Pacheco-Moises, F.P.; Mireles-Ramírez, M.A.; Bitzer-Quintero, O.K.; Delgado-Lara, D.L.; Ramírez-Jirano, L.J.; Velázquez-Brizuela, I.E. Efficacy of melatonin on serum pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress markers in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Arch. Med. Res. 2018, 49, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, M.d.L.V.; Bignotto, M.; Pinto, L.R., Jr.; Tufik, S. Randomized, double-blind clinical trial, controlled with placebo, of the toxicology of chronic melatonin treatment. J. Pineal Res. 2000, 29, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Rajewski, P.; Gackowski, M.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C.; Wesołowski, R.; Sutkowy, P.; Pawłowska, M.; Woźniak, A. Melatonin supplementation lowers oxidative stress and regulates adipokines in obese patients on a calorie-restricted diet. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8494107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, H.R.; Tabatabaei, S.M.H.; Soleimani, A.; Sayyah, M.; Bozorgi, M. The effects of melatonin administration on carotid intima-media thickness and pulse wave velocity in diabetic nephropathy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 48, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Javid, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Gholinezhad, H.; Moradi, L.; Haghighi-Zadeh, M.H.; Bazyar, H. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of melatonin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with periodontal disease under non-surgical periodontal therapy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romo-Nava, F.; Alvarez-Icaza González, D.; Fresán-Orellana, A.; Saracco Alvarez, R.; Becerra-Palars, C.; Moreno, J.; Ontiveros Uribe, M.P.; Berlanga, C.; Heinze, G.; Buijs, R.M. Melatonin attenuates antipsychotic metabolic effects: An eight-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Bipolar Disord. 2014, 16, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazyar, H.; Javid, A.Z.; Zakerkish, M.; Yousefimanesh, H.A.; Haghighi-Zadeh, M.H. Effects of melatonin supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic periodontitis under nonsurgical periodontal therapy: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2022, 27, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larki, R.A.; Iranmanesh, A.; Gholami, D.; Manzouri, L. The effect of oral melatonin on the quality of life, sleep and blood pressure of hemodialysis patients: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, N.; Alizadeh, M.; Akbarzadeh, S.; Rezaei, M.; Mahmoodi, M.; Netticadan, T.; Movahed, A. Melatonin administered postoperatively lowers oxidative stress and inflammation and significantly recovers heart function in patients undergoing CABG surgery. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 585. [Google Scholar]

- Genario, R.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Bueno, A.A.; Santos, H.O. Melatonin supplementation in the management of obesity and obesity-associated disorders: A review of physiological mechanisms and clinical applications. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Kimpinski, K. Role of melatonin in blood pressure regulation: An adjunct anti-hypertensive agent. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 45, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla-Neto, J.; Amaral, F.; Afeche, S.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R. Melatonin, energy metabolism, and obesity: A review. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 56, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Korkmaz, A.; Ma, S. Obesity and metabolic syndrome: Association with chronodisruption, sleep deprivation, and melatonin suppression. Ann. Med. 2012, 44, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, G.; Mania, M.; Abbate, F.; Navarra, M.; Guerrera, M.; Laura, R.; Vega, J.; Levanti, M.; Germanà, A. Melatonin treatment suppresses appetite genes and improves adipose tissue plasticity in diet-induced obese zebrafish. Endocrine 2018, 62, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albreiki, M.S.; Shamlan, G.H.; BaHammam, A.S.; Alruwaili, N.W.; Middleton, B.; Hampton, S.M. Acute impact of light at night and exogenous melatonin on subjective appetite and plasma leptin. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1079453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.X.; Manchester, L.; Fuentes-Broto, L.; Paredes, S.; Reiter, R. Significance and application of melatonin in the regulation of brown adipose tissue metabolism: Relation to human obesity. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owino, S.; Buonfiglio, D.D.; Tchio, C.; Tosini, G. Melatonin signaling a key regulator of glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.H.; Kim, J. Melatonin and metabolic disorders: Unraveling the interplay with glucose and lipid metabolism, adipose tissue, and inflammation. Sleep Med. Res. 2024, 15, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, D. Pleiotropic effects of melatonin. Drug Res. 2019, 69, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, T.d.S.M.d.; Cruz, M.M.; Sa, R.C.d.C.d.; Severi, I.; Perugini, J.; Senzacqua, M.; Cerutti, S.M.; Giordano, A.; Cinti, S.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.C. Melatonin supplementation decreases hypertrophic obesity and inflammation induced by high-fat diet in mice. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, H.; Ahmad, N.; Mishra, P.; Tiwari, A. The role of melatonin in diabetes: Therapeutic implications. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 59, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, T.d.S.M.d.; Paixao, R.I.d.; Cruz, M.M.; de Sa, R.D.C.d.C.; Simão, J.d.J.; Antraco, V.J.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.C. Melatonin supplementation attenuates the pro-inflammatory adipokines expression in visceral fat from obese mice induced by a high-fat diet. Cells 2019, 8, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunet-Marcassus, B.; Desbazeille, M.; Bros, A.; Louche, K.; Delagrange, P.; Renard, P.; Casteilla, L.; Pénicaud, L. Melatonin reduces body weight gain in Sprague Dawley rats with diet-induced obesity. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 5347–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuto, R.; Siqueira-Filho, M.A.; Caperuto, L.C.; Bacurau, R.F.; Hirata, E.; Peliciari-Garcia, R.A.; do Amaral, F.G.; Marçal, A.C.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Camporez, J.P. Melatonin improves insulin sensitivity independently of weight loss in old obese rats. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 55, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.; Topal, T.; Oter, S.; Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J. Hyperglycemia-related pathophysiologic mechanisms and potential beneficial actions of melatonin. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsholme, P.; Keane, K.N.; Carlessi, R.; Cruzat, V. Oxidative stress pathways in pancreatic β-cells and insulin-sensitive cells and tissues: Importance to cell metabolism, function, and dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C420–C433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Ballantyne, C.M. Metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Kwon, H.-S.; Kim, M.-J.; Go, H.-K.; Oak, M.-H.; Kim, D.-H. Melatonin supplementation plus exercise behavior ameliorate insulin resistance, hypertension and fatigue in a rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 92, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.A.R. Effect of melatonin on cholesterol absorption in rats. J. Pineal Res. 2007, 42, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Attwood, S.J.; Hoopes, M.I.; Drolle, E.; Karttunen, M.; Leonenko, Z. Melatonin directly interacts with cholesterol and alleviates cholesterol effects in dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine monolayers. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhiyenko, O.; Sehin, V.; Kuznets, V.; Serhiyenko, V. Melatonin and blood pressure: A narrative review. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gan, J.; Yu, B.; Lu, B.; Jiang, X. Melatonin as a therapeutic agent for alleviating endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: Emphasis on oxidative stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, H.; Jin, C.; Qiu, F.; Wu, Y.; Shi, L. Melatonin mediates vasodilation through both direct and indirect activation of BKCa channels. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2017, 59, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulis, L.; Šimko, F. Blood pressure modulation and cardiovascular protection by melatonin: Potential mechanisms behind. Physiol. Res. 2007, 56, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodella, L.F.; Favero, G.; Foglio, E.; Rossini, C.; Castrezzati, S.; Lonati, C.; Rezzani, R. Vascular endothelial cells and dysfunctions: Role of melatonin. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2013, 5, 119s–129. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, R.J.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D.; Tan, D.X.; Burkhardt, S. Free radical-mediated molecular damage: Mechanisms for the protective actions of melatonin in the central nervous system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 939, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Estaras, M.; Martinez-Morcillo, S.; Martinez, R.; García, A.; Estévez, M.; Santofimia-Castaño, P.; Tapia, J.A.; Moreno, N.; Pérez-López, M.; et al. Melatonin modulates red-ox state and decreases viability of rat pancreatic stellate cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.; Reiter, R.J.; Manchester, L.C.; Yan, M.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardeland, R. Chemical and physical properties and potential mechanisms: Melatonin as a broad spectrum antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardeland, R. Melatonin and inflammation—Story of a double-edged blade. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12525. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, G.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Ricci, L.; Di Serio, T.; Vardaro, E.; Laneri, S. Clinical studies using topical melatonin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimus, D.M.; Popescu, M.R.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Pavel, B.; Zagrean, L.; Zagrean, A.-M. Melatonin’s impact on antioxidative and anti-inflammatory reprogramming in homeostasis and disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.P.H.; Gögenur, I.; Rosenberg, J.; Reiter, R.J. The safety of melatonin in humans. Clin. Drug Investig. 2016, 36, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, H.M.; Steel, A.E. Adverse events associated with oral administration of melatonin: A critical systematic review of clinical evidence. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 42, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menczel Schrire, Z.; Phillips, C.L.; Chapman, J.L.; Duffy, S.L.; Wong, G.; D’Rozario, A.L.; Comas, M.; Raisin, I.; Saini, B.; Gordon, C.J.; et al. Safety of higher doses of melatonin in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 72, e12782. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinali, D.P. Melatonin as a chronobiotic/cytoprotective agent in bone. Doses involved. J. Pineal Res. 2024, 76, e12931. [Google Scholar]

- Givler, D.; Givler, A.; Luther, P.M.; Wenger, D.M.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Shekoohi, S.; Edinoff, A.N.; Dorius, B.K.; Jean Baptiste, C.; Cornett, E.M.; et al. Chronic administration of melatonin: Physiological and clinical considerations. Neurol. Int. 2023, 15, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Region | Study Design | Participants | Sex | Sample Size | Trial Duration (Weeks) | Mean Age | Mean BMI | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG | CG | IG | CG | IG | CG | Melatonin Dose (mg/Day) | CG | ||||||

| Abood et al. 2020 [75] | Iraq | P, R, DB, PC | Women with MetS | ♀ | 20 | 15 | 12 | 45.8 ± 6.5 | 48.0 ± 7.4 | 40.2 ± 6.9 | 41.8 ± 8.8 | 10 | PL (lactose) |

| Agahi et al. 2018 [76] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients treated with antipsychotics | (♀♂) | 50 | 50 | 8 | 37.4 ± 10.3 | 37.4 ± 12.4 | NR | NR | 3 | PL |

| Akhondzadeh et al. 2022 [77] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Women with comorbidities (OW, depression) | ♀ | 21 | 22 | 12 | 35.3 ± 10.6 | 38.5 ± 8.7 | 33 ± 5.4 | 33 ± 5.4 | 3 | PL |

| Al Lami, 2018 [78] | Iraq | P, R, SB, PC | Patients with CKD | (♀♂) | 21 | 20 | 12 | 58.2 ± 15.6 | 56.1 ± 10.7 | NR | NR | 5 | PL |

| Alamdari et al. 2015 [79] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Women with OB | ♀ | 22 | 22 | 6 | 33.8 ± 6.9 | 34.8±7.2 | 34.1 ± 3.2 | 35.7 ± 4.1 | 6 | PL (excipients) |

| Alizadeh et al. 2021 [80] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Women with PCOS | ♀ | 21 | 20 | 8 | 25.5 ± 4.9 | 26.2 ± 5.7 | 28.4 ± 3.8 | 26.9 ± 3.8 | 6 | PL |

| Alizadeh et al. 2021 [81] | Iran | P, R, SB, CO | Patients with COVID-19 | (♀♂) | 14 | 17 | 2 | 37.5 + 8.2 | 34.5 + 8.2 | NR | NR | 6 | Regular medications |

| Amstrup et al. 2024 [82] | Denmark | P, R, DB, PC | Postmenopausal women | ♀ | 17 | 16 | 12 | 63 ± 4.5 | 64 ± 5 | 26.3 ± 4.1 | 24.2 ± 5.5 | 10 | PL |

| Anton et al. 2022 [83] | Romania | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM and PD | (♀♂) | 25 | 25 | 8 | 30–60 | 30–60 | NR | NR | 6 | PL (excipients) |

| Azizi et al. 2025 [84] | Iran | P, R, DB, CO | Methamphetamine-dependent men | ♂ | 23 | 23 | 4 | 18–55 | 18–55 | NR | NR | 10 | NI |

| Bahrami et al. 2019 [86] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with MetS | (♀♂) | 36 | 34 | 12 | 42.5± 9.8 | 42.6± 10.2 | 31.0 ± 4.9 | 32.1 ± 4.9 | 6 | PL (starch) |

| Bahrami et al. 2020 [85] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with NAFLD | (♀♂) | 24 | 21 | 12 | 44 ± 9.6 | 37.7± 11.3 | 29.4 ± 3.6 | 32.5 ± 6.1 | 6 | PL (starch) |

| Basu et al. 2025 [87] | India | P, R, SB, PC | Sedentary men | ♂ | 14 | 14 | 4 | 23.2 ± 1.3 | 22.5 ± 1.0 | NR | NR | 3 | PL (starch) |

| Bazyar et al. 2019 [88] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM & PD | (♀♂) | 22 | 22 | 8 | 53.7 ± 6.6 | 51.4 ± 5.0 | NR | NR | 6 | PL (excipients) |

| Bazyar et al. 2021 [89] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM | (♀♂) | 25 | 25 | 8 | 53.6 ± 4.8 | 51.5 ± 6.3 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 27.4 ± 2.0 | 6 | PL (peppermint oil) |

| Bazyar et al. 2022 [135] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM & PD under NSPT | ♀ | 22 | 22 | 8 | 53.7 ± 6.6 | 51.4 ± 5.0 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 27.2 ± 2.1 | 6 | PL (starch) |

| Celinski et al. 2014 [90] | Poland | P, R, PC | Patients with NAFLD | (♀♂) | 23 | 23 | 56 | 36.1 ± 5.7 | 29.3 ± 9.5 | NR | NR | 10 | PL (liver health supplement) |

| Chojnacki et al. 2011 [93] | Poland | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with UC | (♀♂) | 30 | 30 | 48 | 35.6 ± 11.4 | 33.9 ± 11.7 | NR | NR | 5 | PL (saccharine) |

| Chojnacki et al. 2015 [92] | Poland | P, R, SB, PC | Postmenopausal women | ♀ | 34 | 30 | 24 | 57.9 ± 5.5 | 56.1 ± 5.8 | 30.9 ± 3.1 | 30.1 ± 3.5 | 5 | PL |

| Chojnacki et al. 2018 [91] | Poland | P, R, DB, PC | Postmenopausal women | ♀ | 30 | 30 | 48 | 57.3 ± 6.4 | 56.2 ± 4.1 | 30.9 ± 3.5 | 30.7 ± 3.8 | 8 | PL |

| D’Anna et al. 2017 [94] | Italy | P, R, PC | Women during menopausal transition | ♀ | 16 | 16 | 24 | 49.1 ± 1.7 | 48.7 ± 1.5 | 26.7 ± 4.1 | 25.3 ± 3.7 | 3 | PL (myoinositol) |

| Esalatmanesh et al. 2021 [95] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with RA | (♀♂) | 32 | 32 | 12 | 49.3 ± 10.8 | 49.4 ± 12.7 | 27.2 ± 5.3 | 28.4 ± 5.6 | 6 | PL |

| Farrokhian et al. 2019 [96] | Iran | P, R, TB, PC | Patients with T2DM | (♀♂) | 34 | 36 | 8 | 57.7 ± 8.5 | 57.6 ± 9.1 | 29.3 ± 4.5 | 27.6± 5.0 | 6 | PL (cellulose) |

| Forrest et al. 2007 [97] | UK | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with RA | (♀♂) | 37 | 38 | 24 | 65.1± 2.1 | 60.0 ± 1.8 | NR | NR | 10 | PL |

| Ganjifard et al. 2025 [98] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with COVID-19 | (♀♂) | 23 | 23 | 2 | 62.5 ± 18.6 | 52.8 ± 16.1 | NR | NR | 18 | PL (cellulose) |

| Ghaderi-Zefrehi et al. 2024 [99] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with MetS | (♀♂) | 31 | 32 | 12 | >18 | >18 | 30.2 ± 4.0 | 32.0 ± 5.0 | 6 | PL (starch) |

| Hoseini et al. 2021 [105] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with HFrEF | (♀♂) | 42 | 43 | 24 | 62.7 ± 10.3 | 59.1 ± 11.5 | 26.7 ± 3.2 | 27.2 ± 4.3 | 10 | PL |

| Gonciarz et al. 2012 [100] | Poland | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with NASH | (♀♂) | 30 | 12 | 24 | 41.5 ± 4 | 40.8 ± 3.6 | NR | NR | 10 | PL |

| Goyal et al. 2014 [101] | USA | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with MetS | (♀♂) | 19 | 20 | 10 | 62.7 ± 9.6 | 57.6 ± 10.1 | 35.2 ± 7.0 | 34.1 ± 6.4 | 8 | PL |

| Grossman et al. 2006 [102] | Israel | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with nocturnal HTN | (♀♂) | 19 | 19 | 4 | 62 ± 11 | 66± 11 | 27.4 ±4.5 | 27.3 ± 2.9 | 2 | PL |

| Hannemann et al. 2024 [103] | Germany | P, R, DB, PC | Night-shift workers | (♀♂) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 38.3 ± 11.6 | 34.8 ± 11.5 | 26.1 ± 5.1 | 27.8± 7.7 | 2 | PL |

| Hasan et al. 2022 [104] | Iraq | P, R, CO | Patients with COVID-19 | (♀♂) | 82 | 76 | 2 | 56.8 ± 7.5 | 55.7 ± 8.0 | NR | NR | 10 | NI |

| Jallouli et al. 2025 [106] | Tunisia | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with MS | (♀♂) | 15 | 12 | 12 | 34.6 ± 10.9 | 36.8 ± 8.0 | 23.9 ± 4.2 | 22.9 ± 4.3 | 3 | PL (starch & cellulose) |

| Javanmard et al. 2016 [107] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients underwent CABG | (♀♂) | 20 | 19 | 4 | 60.1 ± 6.3 | 58.6 ± 5.8 | 27.7 ± 3.2 | 29.2 ± 3.7 | 10 | PL |

| Zare Javid et al. 2020 [133] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM & PD | (♀♂) | 22 | 22 | 8 | 53.7 ± 6.6 | 51.4 ± 5.0 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 27.2 ± 2.1 | 6 | PL (excipients) |

| Kari et al. 2019 [108] | Iran | P, R, PC | Postmenopausal women with T2DM | ♀ | 10 | 8 | 8 | 50–60 | 50–60 | 28.3 ± 4.1 | 31.4 ± 4.0 | 3 | PL (MD) |

| Kim et al. 2021 [109] | South Korea | P, R, DB, PC | Women >55 y with insomnia | ♀ | 19 | 19 | 6 | 61 ± 9.6 | 61 ± 4.4 | 24.9 ± 3.2 | 23.6 ± 4.4 | 2 | PL |

| Kotlarczyk et al. 2012 [110] | USA | P, R, DB, PC | Perimenopausal women | ♀ | 13 | 5 | 24 | 50.3 ± 3.0 | 47.5 ± 2.0 | 25.7 ± 3.7 | 21.7 ± 3.5 | 3 | PL (lactose) |

| Larki et al. 2025 [136] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Hemodialysis patients | (♀♂) | 6 | 41 | 41 | 48.9 ± 9.7 | 50.0 ± 12.6 | 27.7 ± 5.4 | 27.3 ± 4.5 | 3 | PL |

| Lauritzen et al. 2022 [111] | Denmark | C, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM | ♂ | 65 | 65 | 12 | 65 ± 21.5 | 65 ± 21.5 | 29 ± 3.5 | 29 ± 3.5 | 10 | PL |

| Leonardo-Mendonça et al. 2017 [112] | Spain | P, R, DB, PC | Resistance-trained athletes | ♂ | 12 | 12 | 4 | 19–30 | 19–30 | NR | NR | 100 | PL (lactose & colloidal silica) |

| Marzougui et al. 2024 [114] | Tunisia | P, R, DB, PC | Hemodialysis patients | (♀♂) | 11 | 11 | 12 | 49.2 ± 10.2 | 49 ± 12.5 | 22.3 ± 2.7 | 23.2 ± 3.9 | 3 | PL |

| Modabbernia et al. 2014 [115] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with schizophrenia | (♀♂) | 18 | 18 | 8 | 32.7 ± 7.3 | 32.8 ± 8.2 | 23.9 ± 3.7 | 23.2 ± 3.2 | 3 | PL |

| Mohammadi et al. 2021 [116] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Individuals with OW or OB | (♀♂) | 19 | 19 | 12 | 38.9 ± 11.6 | 37.8 ± 11.3 | 31.0 ± 2.0 | 30.4 ± 1.6 | 3 | PL |

| Mohammadi et al. 2025 (a) [137] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients underwent CABG surgery | (♀♂) | 17 | 18 | 8 | 64.4 ± 7.9 | 60.2 ± 7.3 | 26.7 ± 4.7 | 26.8 ± 3.6 | 5 | PL (cellulose) |

| Mohammadi et al. 2025 (b) [137] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients underwent CABG surgery | (♀♂) | 17 | 18 | 8 | 61.7 ± 8.9 | 60.2 ± 7.3 | 28.3 ± 5.1 | 26.8 ± 3.6 | 10 | PL (cellulose) |

| Luz et al. 2025 (a) [113] | Brazil | P, R, DB, PC | Morning-shift workers | ♀ | 7 | 9 | 12 | 49.9 ± 6.6 | 45.1 ± 4.3 | 26.0 ± 3.3 | 28.2 ± 3.8 | 0.3 | PL |

| Luz et al. 2025 (b) [113] | Brazil | P, R, DB, PC | Afternoon-shift workers | ♀ | 8 | 7 | 12 | 47.1 ± 5.7 | 48.5 ± 5.8 | 28.3 ± 6.6 | 31.5 ± 4.7 | 0.3 | PL |

| Luz et al. 2025 (c) [113] | Brazil | P, R, DB, PC | Night-shift workers | ♀ | 7 | 8 | 12 | 43.0 ± 3.5 | 50.0 ± 4.9 | 27.8 ± 4.5 | 27.1 ± 5.5 | 0.3 | PL |

| Mousavi et al. 2022 [117] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Women with PCOS | ♀ | 21 | 20 | 8 | 25.5 ± 4.9 | 26.2± 5.7 | 28.4 ± 3.8 | 26.9 ± 3.8 | 6 | PL (MG) |

| Nabatian-Asl et al. 2021 [118] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with SLE | ♀ | 13 | 12 | 12 | 40.6 ± 12.9 | 39.1 ± 9.0 | 26.0 ± 5.6 | 27.5 ± 3.8 | 10 | PL |

| Nunes et al. 2008 [119] | Brazil | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with COPD | (♀♂) | 12 | 13 | 3 | 64.1 ± 9.9 | 67.3 ± 8.1 | 23.8 ± 4.2 | 24.1 ± 4.0 | 3 | PL |

| Ortiz-Franco et al. 2017 [120] | Spain | P, R, DB, PC | Diabetic hemodialysis patients | ♂ | 7 | 7 | 2 | 26.0 ±6.0 | 28.4 ± 4.3 | 25.0 ± 2.2 | 24.7 ± 1.9 | 20 | PL (lactose) |

| Pakravan et al. 2017 [121] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with NAFLD | (♀♂) | 49 | 48 | 6 | 42.5 ± 10.1 | 40.6 ± 9.8 | NR | NR | 6 | PL |

| Panah et al. 2019 [122] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | RT patients with IRI | (♀♂) | 20 | 20 | 4 | 39.2 ± 7.4 | 36.8 ± 8.5 | NR | NR | 3 | PL |

| Rechciński et al. 2010 [123] | Poland | P, R, PC | Patients with CAD | (♀♂) | 40 | 20 | 13 | 61.1 ± 6.7 | 53.6 ± 13.6 | NR | NR | 5 | PL |

| Rezvanfar et al. 2017 [124] | Iran | C, R, DB, PC | Patients with T2DM | (♀♂) | 64 | 76 | 12 | 52 ± 8 | 52 ± 8 | NR | NR | 6 | PL |

| Rigamonti et al. 2024 [125] | Italy | P, R, DB, PC | Adults with OB underwent a BWR | (♀♂) | 9 | 9 | 2 | 27.8 ± 5.6 | 28.8 ± 5 | 43 ± 4.9 | 42.8 ± 4 | 2 | PL |

| Rindone et al. 1997 (a) [126] | USA | C, R, SB, PC | Patients with HC | (♀♂) | 8 | 16 | 6 | 68 ± 9 | 68 ± 9 | NR | NR | 0.3 | PL |

| Rindone et al. 1997 (b) [126] | USA | C, R, SB, PC | Patients with HC | (♀♂) | 8 | 16 | 6 | 68 ± 9 | 68 ± 9 | NR | NR | 3 | PL |

| Rondanelli et al. 2018 [127] | Italy | P, R, DB, PC | Sarcopenic elderly patients | (♀♂) | 42 | 44 | 4 | 81.6 ± 7.0 | 81.8± 6.4 | 24.0 ± 0.8 | 22.8 ± 0.6 | 1 | PL (MD) |

| Romo-Nava et al. 2014 (a) [134] | Mexico | P, R, DB, PC | SGA-treated patients (medium risk) | (♀♂) | 15 | 13 | 8 | 30.6 ± 7.5 | 28.6 ± 9 | 26.1 ± 4.2 | 26.7 ± 5.4 | 5 | PL |

| Romo-Nava et al. 2014(b) [134] | Mexico | P, R, DB, PC | SGA-treated patients (high risk) | (♀♂) | 5 | 11 | 8 | 30.6 ± 7.5 | 28.6 ± 9 | 26.2 ± 5.3 | 24.6 ± 6.1 | 5 | PL |

| Sadeghi et al. 2025 [128] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with CKD | (♀♂) | 20 | 21 | 10 | 64 ± 12 | 65 ± 12 | 29.2 ± 3.5 | 29.9 ± 4.5 | 10 | PL (starch) |

| Sánchez-López et al. 2018 [129] | Mexico | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with MS | (♀♂) | 17 | 16 | 24 | 26–52 | 29–51 | 23.8± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 3.3 | 25 | PL |

| Seabra et al. 2000 [130] | Brazil | P, R, DB, PC | Healthy men | ♂ | 30 | 10 | 4 | 29 ± 6.3 | 29 ± 6.3 | NR | NR | 10 | PL |

| Szewczyk-Golec et al. 2017 [131] | Poland | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with OB (calorie-restricted) | ♀ | 15 | 15 | 4 | 37.7 ± 13.2 | 36.3 ± 16.2 | 37.8 ± 5.8 | 38.2 ± 7.5 | 10 | PL (lactose) |

| Talari et al. 2022 [132] | Iran | P, R, DB, PC | Patients with DN | (♀♂) | 19 | 13 | 24 | 40–85 | 40–85 | NR | NR | 10 | PL (starch) |

| CMRFs | Effect Sizes (n) | Participants (n) | WMD (95% CI) | p-Value | Heterogeneity | Certainty of the Evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | p-Value | ||||||

| Anthropometric parameters | |||||||

| BW (kg) | 27 | 1276 | −0.49 (−1.18, 0.20) | 0.163 | 9.2 | 0.328 | Moderate (II) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 | 1062 | −0.31 (−0.94, 0.32) | 0.338 | 76.6 | <0.001 | Moderate (II) |

| WC (cm) | 20 | 908 | −0.92 (−1.93, 0.09) | 0.073 | 47.2 | 0.011 | High (I) |

| HC (cm) | 9 | 396 | −1.18 (−2.28, −0.08) | 0.035 | 0 | 0.657 | Moderate (II) |

| BFP (%) | 9 | 227 | 0.01(−0.01, 0.03) | 0.296 | 0 | 0.991 | High (I) |

| Glycemic parameters | |||||||

| FBG (mg/dL) | 20 | 958 | −11.63 (−19.16, −4.10) | 0.002 | 98 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| FI (µIU/mL) | 7 | 296 | 0.49 (−1.08, 2.05) | 0.544 | 64.2 | 0.010 | Low (III) |

| HbA1c (%) | 5 | 402 | −0.22 (−0.66, 0.21) | 0.313 | 73.3 | 0.005 | Moderate (II) |

| HOMA-IR | 8 | 280 | 0.15 (−0.18, 0.48) | 0.359 | 15.7 | 0.307 | High (I) |

| Lipid parameters | |||||||

| TG (mg/dL) | 21 | 1047 | −6.10 (−14.69,2.49) | 0.164 | 66.7 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| TC (mg/dL) | 20 | 1006 | −6.97 (−12.20, −1.74) | 0.009 | 73.7 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 20 | 943 | −6.28 (−10.53, −2.03) | 0.004 | 64.7 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 20 | 1005 | 2.04 (0.50, 3.57) | 0.009 | 72 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| Blood pressure | |||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 23 | 1157 | −2.34 (−4.13, −0.55) | 0.011 | 69.7 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 21 | 1069 | −0.88 (−2.19, 0.43) | 0.186 | 73.3 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| Oxidative stress parameters | |||||||

| MDA (μmol/L) | 16 | 671 | −1.54 (−2.07, −1.01) | <0.001 | 95.5 | <0.001 | Very low (IV) |

| TAC (mmol/L) | 12 | 524 | 0.15 (0.08, 0.22) | <0.001 | 96.2 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| Inflammatory parameters | |||||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 21 | 1108 | −0.59 (−0.94, −0.23) | <0.001 | 93.5 | <0.001 | Moderate (II) |

| IL−6 (pg/mL) | 8 | 351 | − 6.43 (−10.72, −2.15) | 0.003 | 98.7 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 11 | 488 | −1.61 (−2.31, −0.90) | <0.001 | 96.1 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| Liver function markers | |||||||

| AST (IU/L) | 8 | 345 | −2.64 (−6.63, 1.35) | 0.194 | 85.5 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 9 | 383 | −2.61 (−4.87, −0.34) | 0.024 | 71.4 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

| GGT (IU/L) | 5 | 188 | −7.21 (−15.20, 0.79) | 0.077 | 88.7 | <0.001 | Low (III) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mohammadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Erfanian-Salim, M.; Alaghemand, N.; Yousefi, M.; Sanjari Pirayvatlou, P.; Mirkarimi, M.; Mavi, S.A.; Alavi, I.; Ettehad, Y.; et al. Comprehensive Effects of Melatonin Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2026, 18, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010134

Mohammadi S, Ashtary-Larky D, Erfanian-Salim M, Alaghemand N, Yousefi M, Sanjari Pirayvatlou P, Mirkarimi M, Mavi SA, Alavi I, Ettehad Y, et al. Comprehensive Effects of Melatonin Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010134

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammadi, Shooka, Damoon Ashtary-Larky, Mahsa Erfanian-Salim, Navid Alaghemand, Mojtaba Yousefi, Pouyan Sanjari Pirayvatlou, Mohammadreza Mirkarimi, Sara Ayazian Mavi, Ilnaz Alavi, Yeganeh Ettehad, and et al. 2026. "Comprehensive Effects of Melatonin Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010134

APA StyleMohammadi, S., Ashtary-Larky, D., Erfanian-Salim, M., Alaghemand, N., Yousefi, M., Sanjari Pirayvatlou, P., Mirkarimi, M., Mavi, S. A., Alavi, I., Ettehad, Y., Mehrbod, M., Asbaghi, O., Suzuki, K., & Reiter, R. J. (2026). Comprehensive Effects of Melatonin Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 18(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010134